The war in Europe had been going for over two years when Jack graduated as Second Lieutenant.

The United States President, Woodrow Wilson, was very reluctant to enter World War I. He declared US neutrality and insisted that both sides respect America’s rights as a neutral country.

Americans were deeply divided about the war in Europe, and how involvement could disrupt progressive reforms. ‘Top of the Pops’ at the time was I Didn’t Raise My Boy to be a Soldier.

In 1916 Wilson narrowly won re-election with a slogan ‘He kept us out of the war’.

Although claiming neutrality, it became clear that the US began to lean towards Britain and France.

Wilson knew that wartime trade with the belligerents was important to the American economy; trade boomed with the Allies.

The cash reserves of the Allies and the Germans were being eaten up by the war effort. They asked the USA for a line of credit and so in October 1915, President Wilson approved loans to both sides, although the Allies were the biggest benefactors. Loans to the Allies totalled $2.25 billion by 1917. On the other hand, Germany had outstanding loans of $27 million.

Germany announced a resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917, which was an extremely provocative move, particularly after Germany sank the Lusitania in 1915, killing almost two thousand people – many of them were Americans.

Germany was bullish about winning the war within five months and therefore even if America entered the conflict it could not mobilise quickly enough to change the course of the war; or so Germany thought.

What really pushed Wilson to the limit of his patience was the ‘Zimmerman Telegram’, a telegram which said that if Mexico went to war with the United States, Germany promised to help Mexico recover the territory it had lost during the 1840s, including Texas, New Mexico, California and Arizona.

The telegram and the fact that Germany attacked three US ships during March led Wilson to ask Congress for a ‘declaration of war’.

In 1917, a senior German official scoffed at American might: ‘America from a military point-of-view means nothing, and again nothing, and for a third time nothing.’ The US Army at the time had only 107,641men.

Within a year, however, the United States raised a five million-man army. By the war’s end, the American armed forces were a decisive factor in blunting a German offensive and ending the bloody stalemate.

To raise troops, President Wilson insisted on a military draft. More than twenty-three million men registered during World War I; and two million, eight hundred thousand draftees served in the armed forces. To select officers, the army launched an ambitious program of psychological testing.

Jack certainly didn’t sit for any psychological testing; he was an officer with the US Marines.

He boarded the troop ship Carpathia at Hoboken on 13th June 1917. He couldn’t believe he was back on the ship that saved his sister, mother and himself after the Titanic sank. This had to be good omen. He disembarked at St Nazaire on 26th June. With him were his best buddy John Younger and fourteen thousand American troops all arriving on various ships around about the same time. These troops would come to be known as ‘Doughboys’.

(Doughboy is an informal term for a member of the United States Army or Marine Corps, especially members of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. They were widely memorialised through the mass production of a sculpture, the Spirit of the American Doughboy. The term dates back to the Mexican–American War of 1846–48.)

The whole operation had been top secret, as the American High Command didn’t want to alert German U-Boats. Nevertheless when they landed, a large and enthusiastic French crowd had gathered to welcome them.

General Pershing had been appointed as the Chief Commander of the American Expeditionary Force. He was well aware that his troops were very green and required more training. He established training camps and organised the supply networks very soon after he arrived in France. He also established the communication networks.

21st October 1917

Luneville France

The first American soldiers entered combat when they were assigned to enter Allied trenches in the Luneville sector near Nancy. Each American unit was attached to a corresponding French unit. Two days later, Lieutenant Jack Doherty was the first American to fire a shot in anger when he discharged a French 75mm gun into a German trench five hundred metres away.

On 2nd November Corporal Thomas Enright and Private Merle Hay of the 16th Infantry became the first American soldiers to die when Germans raided their trenches near Bathelemont.

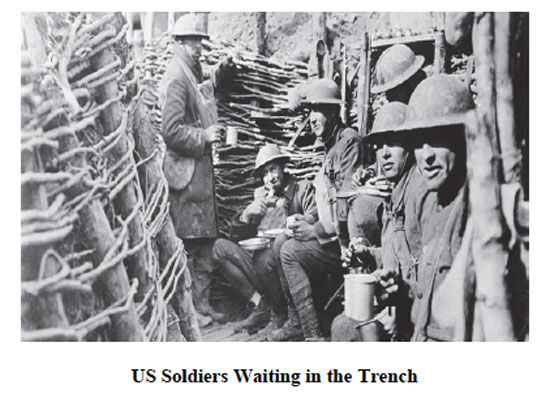

‘Johnnie, how are you going buddy? Handling it okay?’

‘Yeah, I’m fine. Not much happening, is there? I thought we would be in full on combat most of the time, not sitting around this grungy trench with Frenchies who can’t talk to you. Not in English anyway.’

‘Yeah, I know what you mean. It’s hard keeping the men alert while we’re waiting for something to happen.’

‘Holy shit, the bastards are firing shells at us. Keep your head down and make sure your men do the same.’

The German artillery was starting to find its targets. Shells were exploding in the trenches and American soldiers were being blown to hell.

The French Captain assigned to their unit spoke some English. He explained to Jack and John that as soon as the barrage ceased there would be an infantry attack; they and their men needed to be prepared.

Sure enough, the shells stopped and through their periscopes they could see Krauts running towards the Allied positions, firing as they went.

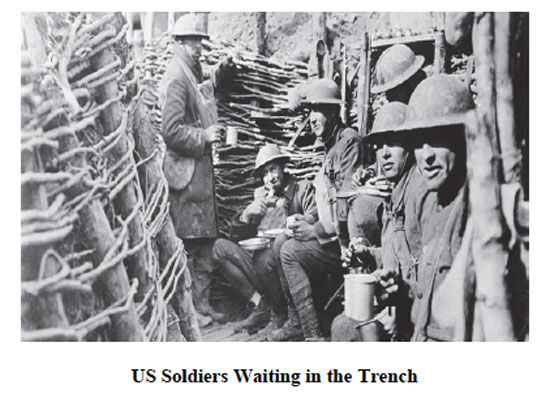

Jack ordered his machine gunners to fire when they had the bastards in their sights. The Lewis machine guns opened fire almost in unison along the line of trenches. Jack could see the Germans dropping like flies but more of the bastards came up from the rear to replace the fallen. This was not going to be easy. The Boche was finding it difficult to make real headway, as no man’s land was a pock-marked muddy moonscape and the intensity of the US and French fire meant the Germans became bogged down.

Eventually, the orders came through to the German officers to pull their men back to their own lines.

Jack observed this happening through his periscope and notified his commanding officer, Captain Phillip Cosser. Captain Cosser notified Infantry Command to shell the retreating Krauts and gave them the coordinates. They were to commence the barrage immediately and cease firing twenty minutes later. His plan was to then go over the top and attack the Germans while they were still in no mans land.

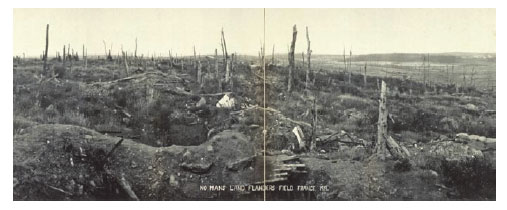

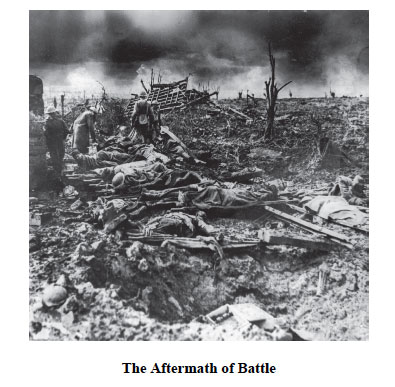

The allied inventory began to create havoc, with Germans being slaughtered across the muddy bog. The smell of fresh blood and torn flesh permeated across to the American trenches causing some of these fresh inexperienced troops to be physically ill.

Twenty minutes had passed and the big guns ceased firing their deadly shells. The order was given, the whistles blew and the troops climbed the ladders and started across no man’s land in pursuit of the enemy. The Krauts had bunkered down in shell craters and old foxholes trying to avoid the American artillery. It was here they created a new line to foil the American-French advance.

The opposing armies were now in open warfare, exposed without any real shelter or protection.

Jack and John and some of the men they led were in a large shell crater, with two Lewis machineguns, which were firing relentlessly at the German positions.

The Germans were proving to be extremely difficult to eliminate and Captain Cosser sent a runner back to the allied trench with a message requesting the artillery give the bastards another pounding.

Suddenly shells began dropping and exploding all around them.

‘Fucking Germans! They’ll not only kill us – they’ll kill their own!’ screamed Jack.

John looked around. ‘Jack, they’re not German shells. They’re coming from our boys. The stupid bastards have got the coordinates wrong!’

The artillery almost destroyed the allied troops and allowed the Germans to return to their trenches to fight another day.

Incredibly Jack and Johnno survived the so-called ‘friendly fire’ and slowly returned to their own trench. A count was taken: Captain Cosser estimated seventy per cent of their troops had been killed. He figured most of these deaths occurred due to their own artillery.

‘It takes five thousand deaths to train artillery to be accurate.’

Captain Phillip Cosser