When Jack arrived at BP as everyone called Bletchley Park, he was impressed with the grand manor house set in beautiful gardens. ‘I can work here’, he thought.

He entered the main entrance, a gothic structure with a griffin on either side guarding the doors to the impressive foyer. At the reception desk sat a very pretty young lady, one of the ten thousand who were either working, or had worked, at Bletchley Park during project ‘Ultra’.

‘Good morning, my name is General Doherty of the United States Marines. I have an appointment with Commander Denniston.’

‘Yes sir. I’ll let his secretary know you are here.’

A tall man who looked more like a university professor than a commander entered the waiting room.

‘Hello General. Alastair Denniston,’ said the commander, extending his arm to shake hands rather than salute.

‘Good morning, Commander.’

‘Please, we are very informal here. Have to be really. Some of the brightest people working on this project are civilians. Now, would you like a tour of our establishment, Jack?’

‘Thank you Alastair. I’m real keen to see what you are up to.’

Commander Alastair Denniston was Operational Head of GC&CS from its formation out of the Admiralty’s Room 40 and the War Office’s MI1B in 1919, until 1942. On the day that Britain declared war on Germany, he wrote to the Foreign Office about recruiting ‘men of the ‘intellectual type’.

Personal networking was used for the initial recruitment, particularly from the universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Aberdeen. Reliable and trustworthy women to perform administrative and clerical tasks were similarly recruited by personal contacts. This has been characterised as recruiting ‘Boffins and Debs’ or ‘Dilly’s Fillies’ (Dilly Knox), and the indexing section where many of the women worked was called ‘The Deb’s Delight’.

Cryptanalysts were selected for various intellectual achievements, whether they were linguists, chess champions, crossword experts, polyglots or great mathematicians. GC&CS was ironically referred to as ‘the Golf, Cheese and Chess Society’. In one instance, the ability to solve a Daily Telegraph crossword in less than twelve minutes was used as a test. The newspaper was asked to organise a competition, after which each of the successful participants was contacted and asked whether they would be prepared to undertake ‘a particular type of work as a contribution to the war effort’. FHW Hawes of Dagenham in Essex finished in less than eight minutes and won the competition itself.

New entrants were given a basic grounding in code-breaking at the Inter-Service Special Intelligence School set up by John Tiltman. Initially at an RAF depot in Buckingham, it moved to an ex-Gas Company showroom in Ardour House, 1 Albany Road, Bedford, which was known locally as the ‘Spy School’.

Working in three shifts or ‘watches’ over twenty-four hours was inaugurated by the Air Section in Hut 10 under Josh Cooper, and the practice soon became universal. The shifts were 4 pm to midnight, midnight to 8 am and 8 am to 4 pm Staff had a six-day week, and rotated through the three shifts. Thirty minutes was allowed for the meal in the middle of the shift.

The irregular working hours affected workers’ health and social life, and the private homes nearby where most staff was billeted. The work was tedious and required concentration, some ‘girls’ collapsed and required extended rest. The staff got one-week’s leave four times a year.

Nine thousand armed services personnel and civilians were working at Bletchley Park at the height of the code-breaking project in January 1945 and over twelve thousand worked there at some point during the war, eighty percent of them women. A relatively small number of men were also employed on a part-time basis, typically for one shift each week when they were used for their Morse code or knowledge of the German language.

Key cryptanalysts included

John Tiltman

Tiltman was an early and persistent advocate of British cooperation with the United States in cryptology. In 1944, he was promoted to Brigadier and appointed Deputy Director of GC&CS. He continued in 1946, as Assistant Director of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), successor to GC&CS. He retired as a Brigadier

Dillwyn ‘Dilly’ Knox

Dilly developed a system known as ‘rodding’, a linguistic as opposed to mathematical way of breaking codes. This technique worked on the Enigma used by the Italian Navy and the German Abwehr, the German intelligence unit. Knox worked in the ‘Cottage’, next door to the Bletchley Park mansion, as head of a research section, which contributed significantly to cryptanalysis of the Enigma.

Knox’s team at the Cottage used rodding to decrypt intercepted Italian naval signals describing the sailing of an Italian battle fleet, leading to The Battle of Cape Matapan. Admiral John Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence credited the Allied victory at Matapan to this intelligence.

Gordon Welchman

Just before World War II, Welchman, an American, was invited by Commander Alastair Denniston to join the Government Code & Cypher School at Bletchley Park, in case war broke out. He was one of four early recruits to Bletchley and made significant contribution to the ‘Ultra’ project.

Alan Turing

Turing is widely considered to be the father of computer science and artificial intelligence.

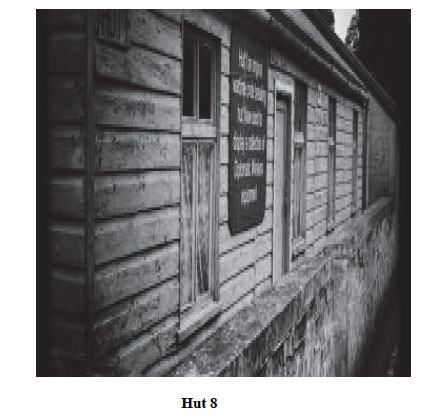

Turing worked for the GC&CS at Bletchley Park. For a time he was head of Hut 8, the section responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German cyphers, including the method of the bombe, an electromechanical machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine.

Hugh Alexander

In February 1940, Alexander arrived at Bletchley Park and joined Hut 6, the section tasked with breaking German Army and Air Force Enigma messages. In 1941, he transferred to Hut 8, the corresponding hut working on Naval Enigma messages. He became Deputy Head of Hut 8 under Alan Turing. Alexander was more involved with the day-to-day operations of the hut than Turing, and, while Turing was visiting the United States, Alexander formally became the Head of Hut 8.

Other key players included:

Harry Hinsley

John Jeffreys

Peter Twinn

Stuart Milner-Barry