The Longest Day

They came, rank after relentless rank, ten lanes wide, twenty miles across, five thousand ships of every description. There were fast new attack transports, slow rust-scarred freighters, small ocean liners, Channel steamers, hospital ships, weather-beaten tankers, coasters and swarms of fussing tugs. There were endless columns of shallow-draft landing ships - great wallowing vessels, some of them almost 350 feet long. … Ahead of the convoys were processions of minesweepers, Coast Guard cutters, buoy-layers and motor launches. Barrage balloons flew above the ships. Squadrons of fighter planes weaved below the clouds. And surrounding this fantastic cavalcade of ships packed with men, guns, tanks, motor vehicles and supplies, … was a formidable array of 702 warships.

The Longest Day

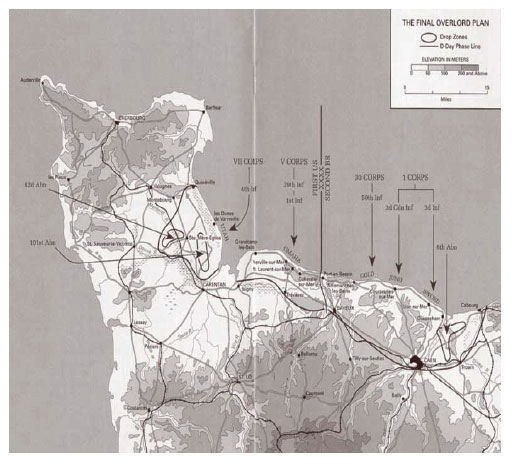

One hundred and sixty thousand Allied troops landed along a fifty-mile stretch of heavily fortified French coastline to confront Nazi Germany on the beaches of Normandy, France.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower called the operation a crusade in which ‘we will accept nothing less than full victory.’ More than five thousand ships and thirteen thousand aircraft supported the D-Day invasion. By day’s end the Allies gained a foothold in Normandy. The D-Day toll was extremely high; more than nine thousand Allied soldiers were killed or wounded.

One hundred thousand soldiers began the march across Europe to defeat Hitler.

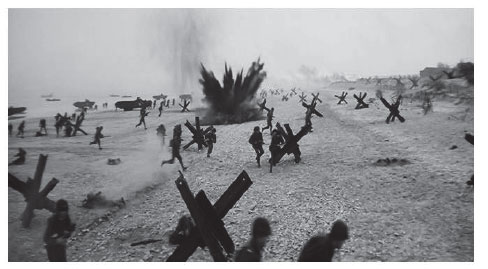

Omaha Beach interconnected the US and British beaches. It was a critical link between the Contentin Peninsula and the flat plain in front of Caen. Omaha was also the most restricted and heavily defended beach: for this reason the experienced US First Division was assigned to land there. The terrain was very difficult. Omaha Beach was unlike any of the other assault beaches in Normandy. Its crescent curve and unusual assortment of bluffs, cliffs and draws were immediately recognisable from the sea. It was the most defensible beach chosen for the D-Day landing. There was the strong opinion that it would be too difficult to land there and too many casualties would result. The high ground commanded all approaches to the beach from the sea and tidal flats, making the Allied troops sitting ducks for the German machine guns. To make matters worse were the narrow passages between the bluffs. Advances directly up the steep bluffs were going to be difficult in the extreme. German machine-gun nests were arranged to command all the approaches and the concrete pillboxes were sited to fire east and west, thereby exposing the Allied troops while themselves remaining concealed from bombarding warships. These pillboxes had to be taken out by direct assault. Compounding this problem was the failure of Allied intelligence to identify a nearly full-strength infantry division, the 352nd, directly behind the beach. Intelligence had them located more than twenty kilometres inland.

Captain Peter Doherty was at the back of the LCA (Landing Craft Assault) when it hit the beach, the ramp dropped and the marines waded through the water and up onto the beach.

Bullets and shells were raining down on the invading troops. Soldiers and marines were dropping everywhere and the sand was stained with the blood of the wounded and dead.

Peter started up the beach. He saw a wounded marine, crawling towards the cliff face. He crouched down beside him and asked to look at the wound. The young marine pointed to his stomach. Peter lifted his shirt and saw a small hole in the centre of his abdomen. He rolled the young man over to see his back. It was as Peter suspected - the exit wound was as big as his fist. This marine wasn’t going home. Peter could do no more than reassure him and make him as comfortable as possible in the circumstances.

Doherty kept crawling up the beach, dodging bullets and shells. He couldn’t believe the number of dead all over the beach. He spotted another marine, this time wounded in the leg. Peter was able to apply a bandage and called for the stretcher-bearers to take him to the LCA for transfer to the hospital ship. His knee had been shattered.

Peter was not overly religious, but seeing the mayhem around him, the dead, the dying, the wounded crying out in pain …

‘This is what hell must be like,’ he thought.

Doherty and his team managed to transfer twenty wounded to the hospital ship. The LCA was now on its way back for the next batch.

The young captain had been on duty for twenty-three hours, collecting the wounded and transferring them to the hospital ship for extensive treatment. He and his medical team also tended the wounded on the beach, stitching and bandaging the young frightened soldiers and sending them on their way to who knows what.

Two LCAs laden with American wounded received direct hits from the German artillery. Their second chance was obliterated in seconds.

Omaha Beach 7th June

Captain Doherty returned to Omaha Beach the next day; there were spent shells and bullets littering the sand.

Bodies of Allied soldiers remained where they had fallen, distorted and bloodied, a grim reminder of what had transpired the day before.

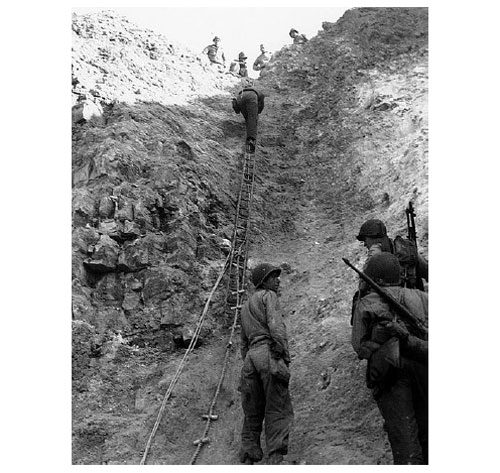

Peter’s orders were to follow his company inland and establish a dressing station to tend the wounded. The team were able to scale the cliffs using rope ladders and made their way inland. They found an old farmhouse which Peter decided would be adequate for the station.

Once the dressing station had been established the medical team waited for the wounded to arrive. They didn’t have to wait long - a constant stream of soldiers began to materialise, most of them being carried by stretcher-bearers, others were the walking wounded.

The VII Corps advanced westwards to cut off the Cotentin Peninsula. An additional three infantry divisions had landed to reinforce the Corps. Major General J. Lawton Collins, the Corps Commander, drove his troops hard, replacing units in the front lines or sacking officers if progress was slow.

The medical teams, including Peter’s, were having trouble keeping up the pace. No sooner had they established a new dressing station than they would have to pack up and move forward. The wounded were taken back to Omaha Beach to be transported to the already overcrowded hospital ships.

By day six C-46 and C-47 cargo planes were flying across the English Channel to land on improvised runways on the Normandy beachhead.

The planes ferried badly wounded men to hospitals in Great Britain. It was the job of the flight nurses to take care of the twenty-four wounded soldiers each plane could carry. Some men were missing arms or legs; others had head or chest wounds.

The Germans facing VII Corps were a mix of regiments and battle groups from several divisions, many of which had already suffered heavy casualties fighting the American airborne troops in the first days of the landings. Very few German armoured or mobile troops could be sent to this part of the front because of the threat to Caen further east. Infantry reinforcements arrived, but slowly.

By 16th June there were no further natural obstacles in front of the American forces. The German command was in some confusion. General Rommel and other commanders wished to withdraw their troops in good order into the Atlantic Wall fortifications of Cherbourg, where they could have withstood a siege for some time. Adolf Hitler, issuing orders from his headquarters in East Prussia, demanded that they hold their present lines even though this risked disaster.

Captain Doherty was transferred to the 79th Division as they had lost a significant percentage of their medical Corps in the fighting. Two days later, Peter’s new battalion and a significant contingent of men and machinery from other Divisions, were on the outskirts of Cherbourg.

Major General Lawton Collins was in charge of the operation. He was confident they would be able to take Cherbourg in the next twenty-four hours. However, Lieutenant General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, the German garrison commander defending the port city, thought otherwise. He had twenty-one thousand men at his disposal, however; they were either inexperienced or totally exhausted. Food, fuel and ammunition were short.

‘I know that Hitler will send us reinforcements any day now. We just have to hold out until then,’ Von Schlieben assured his second-in-command.

‘What are our exact orders, General Von Schlieben?’

‘The Führer has demanded that we fight to the death.’

Later that day, as the US troops were progressing towards the city, German planes were seen overhead. But they were not dropping much needed supplies - Hitler had ordered they drop Iron Crosses to be awarded to the brave men of Cherbourg.

‘Fight to the last man. I think we’ll have to,’ Von Schlieben complained.

Major General Collins issued a demand to the Germans to surrender the city and save many German and US lives but General Von Schlieben refused, based on orders from Hitler.

Collins subsequently launched a general assault on 22nd June. Resistance was stiff at first, but the Americans slowly cleared the Germans from their bunkers and concrete pillboxes. On 26th June, the 79th Division captured Fort du Roule, which dominated the city and its defences. This finished any organised defence. Von Schlieben was captured. The harbour fortifications and the arsenal surrendered a few days later, after a token resistance. Some German troops, cut off outside the defences, held out until 1st July.

Captain Peter Doherty and his team marched into Cherbourg, along with twenty-five thousand other US troops.

Hitler was devastated and held Von Schlieben responsible as a very poor role model and leader.

By July the 79th Division had taken Lessay, crossed the Sarthe River and in early August entered Le Mans. In September they had moved east to the Franco-Belgian border frontier and crossed the Moselle River. Casualties were high and the logistics for evacuating the wounded weren’t getting any easier.

The Division was given time off after such an arduous and costly few months. The Division regrouped, refreshed and readied itself to march into Germany. They moved across the Moder River in November, and through Haguenau. In December they encountered the Siegfried Line. From December until early February 1945, the Division fought many engagements around the Moder, most of them defensive until they were able to go on the offensive again.

Peter and his team were attending the wounded in the dressing station when a hail of bullets went through the station. Several of the wounded were hit as well as one of the nurses. Peter received a wound to the right leg just above the knee and another in his hip. His medical comrades attended him and a transport aircraft was summoned to take him and the other wounded back to England to be treated.

This would be the end of Peter’s war.

He was flown home to the United States in May 1945.