Changi was one of the more notorious Japanese prisoner of war camps. Changi was used to imprison Malayan civilians and Allied soldiers. The treatment of POWs at Changi was harsh but fitted in with the belief held by the Japanese Imperial Army that those who had surrendered to it were guilty of dishonouring their country and family and as such deserved to be treated in no other way.

For this reason, forty thousand men from the surrender of Singapore were marched to the northern tip of the island where they were imprisoned at a military base called Selerang, near the village of Changi. The British civilian population of Singapore was imprisoned in Changi Prison itself, one mile away from Selerang. Eventually, any reference to the area was simply made to ‘Changi’.

For the first few months the POWs at Changi were allowed to do as they wished with little interference from the Japanese. There was just enough food and medicine provided and to begin with the Japanese seemed indifferent to what the POWs did. Concerts were organised, as were quizzes and sporting events. The camp was organised by the officers into battalions and regiments and strong military discipline was maintained. However, by Easter 1942, the attitude of the Japanese had changed. They organised work parties to repair the damaged docks in Singapore and food and medicine became scarce. More significantly, the Japanese made it clear that they had not signed the Geneva Convention and that they ran the camp based on their own rules.

As 1942 moved on, deaths from dysentery and vitamin deficiencies increased dramatically.

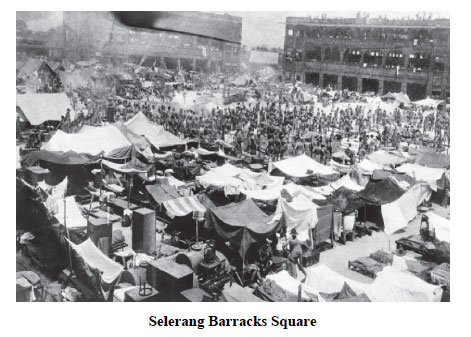

Four Allied POWs - two Australians and two British - attempted to escape, enraging the Japanese administration, who demanded that everyone in the camp sign a document declaring that they would not attempt to escape. This was universally refused. As a result, twenty thousand POWs were herded into the Selerang Barracks Square and told that they would remain there until the order was given to sign the document.

The Selerang Barracks, originally built to accommodate eight hundred men, consisted of a parade ground surrounded on three sides by three-storey buildings. A number of smaller houses for officers and married couples were spread out in the spacious grounds. Nearly twenty thousand men crammed into a parade ground of about one hundred and twenty-eight by two hundred and ten metres.

An Australian POW, George Aspinall documented the situation:

The first and most urgent problem we had to face up to was the lack of toilet facilities. Each barracks building had about four to six toilets, which were flushed from small cisterns on the roofs. But the Japanese cut the water off, and these toilets couldn’t be used. The Japanese only allowed one water tap to be used, and people used to line up in the early hours of the morning and that queue would go on all day. You were allowed one water bottle of water per man per day, just one quart for your drinking, washing, and everything else. Not that there was much washing done under the circumstances.’

Dr Harry de Neville was becoming very concerned with the health of the troops and he, along with Lieutenant Colonel ‘Weary’ Dunlop, knew that if this stand-off lasted much longer men were going to die.

‘We need to get access to more clean water Lieutenant Colonel. If we don’t, they’ll start dropping like flies.’

‘I know Harry. By the way, call me ‘Weary’. Everyone else does.’

‘Why do they call you Weary?’

‘It’s my surname - Dunlop. Tyres. Weary.’

‘Oh, I get it. Anyway - do you think we could approach the Japanese? See if we can increase the water ration?’

‘Harry, we can try. But I think these bastards are going to refuse. Until the assurance of non-escape is signed they’re going to squeeze tighter and tighter.’

‘Do you reckon we all should sign it and end this fucking stalemate?’

‘I do. It’s not worth the rice paper it’s written on.’

Harry and Weary made a heartfelt plea to the Japanese commander.

‘Sir, we beg you to increase the food and water ration to our men. It’s causing dysentery and other illnesses. These could spread throughout the entire group.’

‘I will increase the ration as soon as your stubborn men sign the document. We have politely asked them to sign. Not before.’

Harry and Weary retreated to the barracks knowing that more and more prisoners would die each day they were detained in the unholy square.

After three very hot and humid days and despite the oppressive conditions, the POWs still refused to back down.

General Fukuye ordered the commander of the British and Australian troops in Changi, Lt-Gen E. B. Holmes, and his deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Galleghan, to attend the execution of the four recent escapees: Breavington, Gale, Waters and Fletcher. One of the Australians, Breavington, pleaded to no avail that he was solely responsible for the escape attempt and should be the only one executed. The Indian National Army guards carried out their executions with rifles on 2nd September. The initial volley was non-fatal, and the wounded men had to plead to be finished off.

This action had no effect on the POWs’ position. The Japanese pulled out ten men and marched them to the local beach and shot them all. Despite this, still no-one signed the document.

Only when the men were threatened with an epidemic by moving the hospital into the square was the order given that the document should be signed.

Harry and Weary had made it very clear to the officers that moving the sick into the barracks would not only finish off their patients, it would spread disease throughout the ranks – they were already at the end of their tether.

However, having agreed, the commanding officer made it clear that the document was non-binding, as it had been signed under duress. He also knew that his men desperately needed the medicine that the Japanese would have withheld if the document had not been signed. But this episode marked a point of no return for the POWs at Changi.

Harry and Julie had not seen each other since Julie farewelled Harry at Government House that terrible day when the Japanese marched into Singapore. She assumed he was alive although she had heard of the rumours of a massacre at Alexandria Hospital where they both worked. She knew Harry - he would have managed to live.

Being a doctor, Julie was kept busy with looking after the three thousand-odd civilian prisoners at the second Changi Prison, quite close to where Harry was being held.

The civilians were slightly better off than the POWs, with better food rations and water but very little medicine. This made Julie’s job all the more difficult.

As in the men’s prison, dysentery and malaria were the greatest killers.

Little Lara was feeling the effects also. Julie had difficulty in finding the right food for her natural development. Milk was virtually non-existent; the closest Julie could acquire was coconut milk.

She was near the perimeter fence hoping to get a glimpse of Harry, something she did regularly but without success. This day, she saw two men with a Japanese escort striding over the parade ground heading for the commander’s office. She swore it was Harry but couldn’t be sure - the man was terribly skinny and wore a hat. She dare not yell out, as she would be beaten severely for unruly behaviour. She waited until the two men returned to the male prison. This time she was sure it was Harry, her darling Harry. She now knew for certain that her beloved husband was alive.

The Japanese used the POWs at Changi for slave labour. The formula was very simple; if you worked, you would get fed. If you didn’t work, you would starve. Men were made to work in the docks where they loaded munitions onto ships. They were also used to clear sewers damaged in the attack on Singapore. The men who were too ill to work relied on those who could work for their food. Sharing what were already meagre supplies became a way of life – true mateship.

The number of POWs kept at Changi dropped quite markedly as men were constantly shipped out to other areas in the Japanese Empire to work. Men were sent to Borneo or Thailand to work on the Burma-Thai railway or to Japan itself where they were made to work in the mines. More captured soldiers, airmen and sailors from a variety of Allied nations replaced them. Malaria, dysentery and dermatitis were common, as were beatings for not working hard enough.

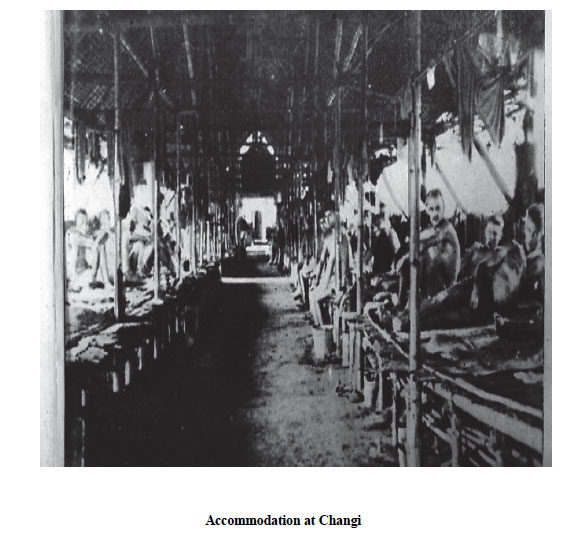

In 1943, the seven thousand men left at Selerang were moved to the prison in Changi. It was built to hold one thousand. The Japanese crammed five or six men in a cell designed for one. With such overcrowding, disease was rife and spread throughout the prison. The majority of the Red Cross parcels were never distributed; therefore the men at Changi had to rely on their own wits to survive. An example of POW ingenuity was that the army medics made tablets convincing the Japanese guards they were a cure for VD. The tablets became a best seller and they could then buy genuine medicine for their own men in an attempt to aid those who were sick.

As the end of the Pacific War approached, rations to the POWs were reduced and the work requirement increased. POWs were forced to dig tunnels and foxholes in the hills around Singapore, affording the Japanese places to hide and fight when the Allies finally reached Singapore.

Many POWs believed that the Japanese would kill them as the Allies got near to Singapore. This never happened. When Emperor Hirohito told the people of Japan that the war ‘has gone not necessarily to our advantage’, the Japanese soldiers at Changi simply handed over their weapons and became prisoners themselves.

By the time Changi was liberated over eight thousand Australian POWs had died. The British lost over twelve thousand.