And in the Jungle

Tom was promoted to Captain and assigned to the Saratoga, a Lexington-class aircraft carrier built for the United States Navy during the 1920s. Originally designed as a battle cruiser, she was converted into one of the Navy’s first aircraft carriers during construction to comply with the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. The ship entered service in 1928 and was assigned to the Pacific Fleet for her entire career. Saratoga and her sister ship, Lexington, were used to develop and refine carrier tactics in a series of annual exercises before World War II. On more than one occasion these included successful surprise attacks on Pearl Harbour, Hawaii - ironic! She was one of three pre-war US fleet aircraft carriers, along with Enterprise and Ranger, to serve throughout World War II.

Tom’s first major engagement was Guadalcanal.

Japanese troops arrived on Guadalcanal on 8th June 1942, to construct an air base. Strategically, to possess an air base was important if Japan was to control the lines of communication between the United States and Australia. American marines landed two months later, and included in that contingent was Captain Tom Doherty. Their objective was to capture the airfield hence protecting the important sea-lanes. Up until then, few people outside the South Pacific had ever heard of that two thousand five hundred square-mile speck of jungle in the Solomon Islands. The following six months would ensure Guadalcanal was as well known as Pearl Harbour and would prove to be the turning point in the Pacific war.

Operationally, the Battle of Guadalcanal was notable for the interrelationship of a complex series of engagements on the ground, at sea, and in the air. Tactically, what stood out was the resolve and resourcefulness of the US Marines, supported by Australian and New Zealand troops whose tenacious defence of the air base dubbed ‘Henderson Field’ enabled the Americans to secure air superiority.

By the end of the battle on 9th February 1943, the Japanese had lost two-thirds of the thirty-one thousand army troops committed to the island, whereas the US and its allies had lost less than seven thousand soldiers of the sixty thousand deployed. The ship losses on both sides were heavy. The US lost twenty-eight while the Japanese Navy lost thirty-eight. But by far the most significant loss for the Japanese was the decimation of their elite group of naval aviators. Japan, after Guadalcanal, no longer had a realistic hope of withstanding the counter offensive of an increasingly powerful Allied force.

Tom Doherty was watching the men in his company board the amphibious landing craft (LVCP). The last craft, number seven had one space left: it was his.

The landing force split into two groups, with one group assaulting Guadalcanal, and the other, including Tom’s D Company, attacking Tulagi and nearby islands. Allied warships bombarded the invasion beaches while US carrier aircraft bombed Japanese positions on the target islands and destroyed fifteen Japanese seaplanes at their base near Tulagi.

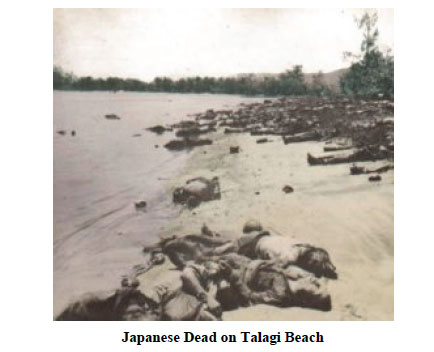

Three thousand US Marines assaulted Tulagi and two nearby small islands, Gavutu and Tanambogo. The Japanese defending the naval and seaplane bases on the three islands fiercely resisted the Marine attacks. Tom’s D Company fought ferociously, supported by the other Marines and they eventually secured all three islands Tulagi on 8th August, and Gavutu and Tanambogo by 9th August. The Japanese defenders were killed almost to the last man, while the Marines suffered one hundred and twenty-two killed, ten from D Company.

Tom ordered his troops to surround Henderson Field to ward off any Japanese Attacks. He knew the Japanese strength had been much depleted but he also knew they were likely to bring in fresh troops with the objective to retake the airfield.

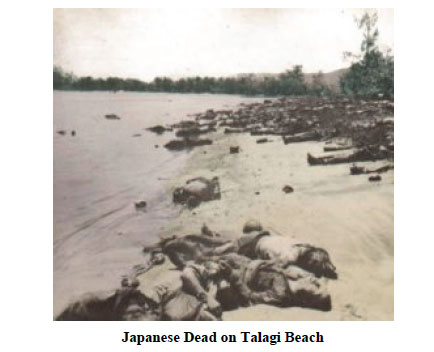

He was right. It was quickly reinforced with elements of the Japanese 17th Army in the form of a brigade of eleven hundred men under Colonel Kiyono Ichiki, whose forces had originally been designated for the assault on Midway two months earlier.

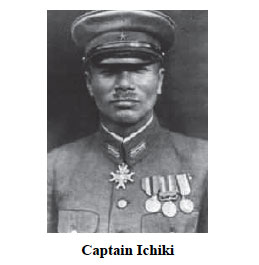

Tom was walking the perimeter of the airbase at about 11 pm checking the defences and ensuring his men were alert and ready for an attack. A sergeant approached him accompanied by an islander, Jacob Vouza. Jacob had been employed as a scout. Tom could not help notice that Vouza had been badly wounded and should receive medical attention but Jacob insisted on speaking to Tom first. Vouza’s ability as a scout had already been proven when the US 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal on 7th August 1942. That same day, Vouza rescued an aviator from USS Wasp who was shot down in Japanese-held territory. He guided the pilot to American lines where he met the Marines for the first time.

On 20th August, while scouting for suspected Japanese outposts, soldiers of the Ichiki detachment, a battalion-strength force of the Japanese 28th Infantry Regiment, captured Vouza. Having found a small American flag in Vouza’s loincloth, the Japanese tied him to a tree and tortured him for information about Allied forces. Vouza was questioned for hours, but refused to talk. He was then bayoneted in both of his arms, throat, shoulder, face, and stomach, and left to die.

After his captors departed, he freed himself by chewing through the ropes and made his way through the miles of jungle to American lines.

‘Boss, I must warn you. There’s many Japs. Maybe two hundred and fifty, maybe five hundred. Coming to attack you any minute.’

‘How do you know this Jacob?’

Jacob explained to Tom what had happened to him and how he had heard the Japanese soldiers talking amongst themselves about their plans. They certainly didn’t reckon on Jacob living and divulging their plans to the Americans.

Tom quickly alerted his men of the imminent attack.

‘OK fellas! All hell is about to break loose. Any rumours you may have heard about the Japs being invincible is crap. They bleed just like the rest of us. They’re shit-scared when they feel the cold hard steel of a bayonet.

‘You know the old British order ‘don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes’? Bullshit! Start firing as soon as you hear any fucking noise in the jungle! And don’t stop shooting until they stop returning fire. We’ve got the big guns to back us up so chances are they’ll kill most of the little bastards before we even have to fire a shot. Good luck boys, do your best.’

Tom ran back to his command position at the airfield. The first shots were heard at midnight; the last were at 5 pm. The Japanese commander, Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki, had underestimated the strength of the allied forces opposing him.

Ichiki’s assault was defeated with heavy Japanese losses in what became known as the ‘Battle of the Tenaru’. When day broke, Captain Tom Doherty’s company along with the other US companies counterattacked Ichiki’s surviving troops, killing many more of them. The dead included Ichiki himself, though it has been claimed that he committed seppuku after realising the magnitude of his defeat, rather than dying in combat. In total, all but one hundred and twenty-eight of the original nine hundred and seventeen members of the Ichiki Regiment’s First Element were killed in the battle.

The Marines suffered thirty-four killed and about eighty wounded. Ten marines were captured - unfortunately one of the ten was Tom. He had entered the jungle fringe when he heard a noise after the battle had ceased; it was a well-armed Japanese soldier; a captain like him.

His Japanese captor disarmed him and proceeded to march him deeper into the jungle until they reached a small group of soldiers. They all jumped up and started to prod him with their bayonets but the Captain ordered them to stop and instructed two soldiers to tie Tom to a tree. There was Tom, bound to a large tree while his captors were discussing what to do with him. Despite only knowing a few Japanese words he got the gist of the conversation.

They were divided between the ‘let’s torture the bastard, learn what he knows and then kill him’ as opposed to ‘let’s take him back and keep him as a POW’.

Finally Captain Ichino decided they would take Tom back to what was left of their camp and transport him over to a POW camp in Singapore.

Tom was loaded onto a merchant ship along with the other nine prisoners. They were placed in a cargo hold for the five-day journey to their new home. They were given very little food, mainly rice and inadequate amounts of water. The temperature in the airless cavern was estimated to be forty degrees and the humidity level was ninety per cent, an almost deadly environment.

When the ship berthed at Singapore dock and the covers were removed from the hold the nine prisoners could hardly move. The Japanese guards encouraged them with bayonets and whips. Tom and his shipmates were thrown onto the back of an army truck and taken over very rough roads to a POW camp called the River Valley Road Camp. It was right in the heart of Singapore and detained mainly Australians with some American POWs.

The routine for Tom and the other prisoners was harsh; the guards would often whip them for the slightest indiscretion and on occasion they were forced to witness a beheading.

January 1945

Tom and about nine hundred prisoners from the United States and Australia mainly, were herded into the parade ground and then marched through the streets of Singapore and down to the docks. There waiting for them were a number of rusting old cargo ships.

‘The guards using bamboo sticks forced us all into the hold. Cattle were treated better. I had experienced a similar hellhole before but not with so many men.’