Tom Doherty’s Account

The Japanese guards made it clear they wanted around four hundred and fifty of us in each hold.

The poor bastards below were shouting and pleading for them not to let any more men in. But the louder they shouted the more intense the guards became pushing us down into the depths of hell.

I had suffered under the Japanese since my capture but nothing had prepared me for this. The only slightly amusing thing was the name of the ship: Fuku Maru.

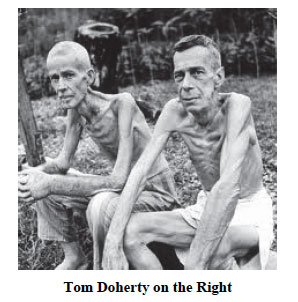

In the hold there was standing room only for us poor wretches, all of us packed in like sardines, with no toilet facilities. Most had dysentery, malaria and beriberi, a disease caused by our limited diet and marked by pain and paralysis.

The guards battened down the hatches, the rank, humid, black dungeon creating a claustrophobic terror amongst the men. These horrible ships were unknown to us but would eventually be known as ‘hell ships’ and with good reason. Some of the most macabre episodes of the war occurred on these ships- men driven crazy by thirst killed fellow prisoners to drink their blood.

Submarines and aircraft sank nineteen of the fifty-six hell ships; many of the allied prisoners were killed in these attacks by their own side. Twenty-two thousand POWs died en route to camps in Japan and Taiwan.

Down in the bowels of the Fuku Maru the heat was unbelievable. Temperatures quickly reached in excess of 45C.

I could not move. No one could. You couldn’t sit or lie down. And the smell was indescribable; an overpowering stench of excrement, urine, vomit, sweat, weeping ulcers and rotting flesh clogged the atmosphere.

Thirst became our biggest problem. At no time were we given water, none whatsoever. You start to hallucinate and see mirages, and that is the most dangerous thing. People died down in the holds from suffocation or heart attacks. Their bodies lay among us.

Six days out of Singapore, I wondered how much more I could take. Then, I felt a tremendous blast - a torpedo tore through the hold. The ship shuddered and listed. We were going down.

A pack of US submarines had attacked the convoy not knowing the nature of the pitiful human cargo.

The water was lapping the hatches and by some miracle I was washed out. The sea was a mass of thick oil emanating from the twelve Japanese hell ships that had been sunk by the attack. Those of us who could swim were the only ones who survived.

I put my head down and swam like I had never swum before gulping oil the whole time, surrounded by debris and flames. I thought I would never make it. But I did.

When I was a safe distance from the sinking ship I stopped swimming and trod water for a while. The scene was one of sinking ships, fire on the water and bodies floating everywhere.

Two hundred and forty-four of my comrades on the Fuku Maru died that night. They had survived the camps and the horrendous work details, the starvation and the conditions in the holds of the hell ships only to be killed by ‘friendly fire’.

I had been able to grab a single-man life raft as it came floating past. Exhausted, I hauled myself into it.

As night descended so did the temperature. It became bitterly cold but I knew the only way to survive was to stay awake. With the sunrise, I could see what surrounded me - water, nothing else, just an endless horizon of water. I could barely see due to the unrelenting glare reflecting off the water. The sunburn was becoming intense and I developed salt-water immersion sores which were made even more painful when crude oil got into the fissures. I wondered if I would have been better off dying like my comrades.

As the sun set and it became night it became bitterly cold once more.

By the time the sun rose on the fifth day, I could no longer see. I had no eyebrows or hair on my head. I think the sheer shock of what was happening to me had caused my hair to fall out. I fell into a trance-like state. I was on the edge of death.

As I lay there waiting to die I heard shouting and the sensation of being dragged onto a boat. I was then transferred to a Japanese whaling vessel. I was being dropped off at a port where there were other shipwrecked POW survivors. There must have been at least one hundred of us.

We were then paraded naked through the village, apparently as some form of punishment. Some of the locals turned their backs on this demeaning procession, others jeered and spat at us. I was past caring.

And then something incredible happened. As we stumbled along in the pouring rain, someone started singing Singin’ In The Rain. Slowly, we all joined in with altered lyrics crudely deriding our captors, unbeknownst to them. Even after all we had been through, we were

defiant, our spirits unbroken.

9th August 1945 began as any other day in the POW camp; everybody had morning chores to complete before the hard labour began in the Mitsubishi factory. I was regarded as the lucky one - I tended the officers’ vegetable garden.

That same morning Captain Charles Sweeney, a young US Air Force officer, aged just twenty-five, same age as myself, was beginning a day that would be anything but normal.

We didn’t know that three days prior, an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. This catastrophic bomb did not alter the Japanese hierarchy’s opinion that they should fight to the death.

President Harry Truman decided that another strong message should be sent.

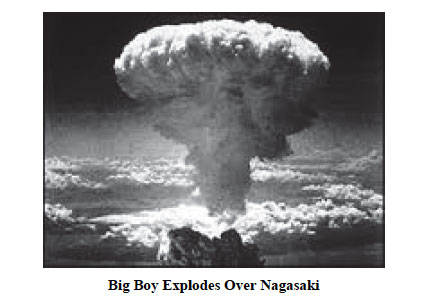

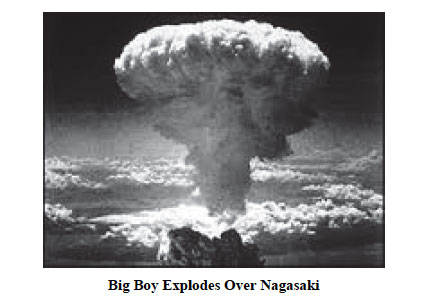

Sweeney’s mission was to deliver an A-bomb named ‘Fat Man’. At over ten feet long and five feet in diameter, it weighed in at 10,200lb.

At around midday the task I detested most was due to be done, emptying the shit-cans on to the Japanese officers’ vegetables. I dry retched as usual; I just couldn’t get used to that horrible stench. In its favour was the effect it had on the vegetables that were bigger and more tasty than any vege I had eaten before.

I had just completed the unpleasant task when a tremendous clap of thunder shook the very ground I was standing on. It appeared to have originated from Nagasaki city. Soon afterwards a gust of hot wind blew my one hundred-pound frame right off my feet.

Later, the other prisoners came back from their day at a nearby Mitsubishi factory and began to talk of a massive bomb raid. No one was really sure what had happened – other than it was huge.

We later learnt temperatures at ground zero were between 3,000 C and 4,000 C.

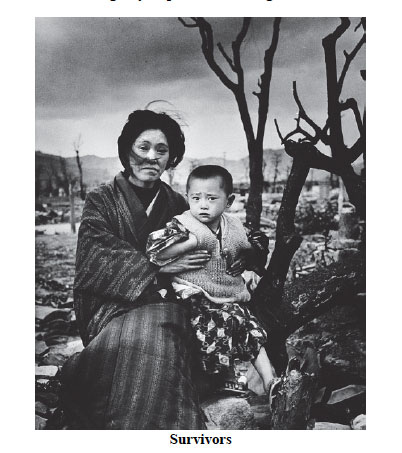

The entire area had been flattened and thirty-nine thousand Japanese had been vaporised instantly by this bomb.

For several days at our camp, it was business as usual - the usual workloads, the usual beatings, and the usual meagre rations. Then on 21st August we were paraded and the Japanese commander read out the declaration of the cessation of hostilities. The war was over.

We all wondered when we would be rescued. It was time to go home.

I was working in my vegetable garden when I saw several trucks and Jeeps speed up to the camp gates. US Marines jumped out looking the epitome of American soldiers dressed in khaki, neatly pressed and waving to us as we ran towards them. They distributed cigarettes and chocolate bars. It was a frantic scene of hugs and handshakes.

Men were shouting and screaming, throwing things in the air, weeping and kissing the earth, lost in emotion. I jumped on one of the first trucks to speed out of the camp towards Nagasaki harbour, where a ship was waiting to escort us to freedom.

Looking out from the lorry we viewed absolute devastation, a scene from Dante’s Inferno.

What finally dawned on me was that I had survived the most destructive bomb ever detonated. I was going home to Chesapeake Bay.’