The Turkish Coast stretches all the way from Thrace and the Dardanelles to Antakya near the Syrian border. This section focuses on the areas most popular with western tourists, covering the entire Aegean, and the Mediterranean as far east as Alanya. The chapter divisions take in all the main resorts as well as excursions to ancient sites.

Poppies in Pergamon

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The North Aegean

Known today as the Dardanelles, but to the ancients as the Hellespont, these straits, only 1,200m (3,937ft) wide at their narrowest point, mark the division of Europe and Asia, and the Sea of Marmara (the ancient Propontus) from the Aegean. They have proved a strategic and romantic challenge to both military heroes and brave fools. Leander swam across by night to visit his lover, Hero; English poet Lord Byron swam across for fun in 1810. The Persian army, led by Xerxes, crossed the straits on a bridge of boats in 480BC in a failed bid to conquer Greece; Alexander crossed in 334BC to defeat the Persians. The north shore comprises the Gallipoli Peninsula; on the south flank stands Troy. This is truly a fitting introduction to a coast of legends.

Gallipoli (Gelibolu)

Those who are not military history buffs might shy away from visiting Gallipoli 1 [map], but anyone who comes here will be moved by the immense tragedy and dignity of the story told throughout this beautiful and now peaceful peninsula. In late 1914 and early 1915, at the instigation of an inexperienced Winston Churchill, in his first major role as First Lord of the Admiralty, the British and French made several attempts to force the Dardanelles and sail a fleet to Constantinople, but were repulsed by Ottoman mines with heavy losses. Subsequently, on 25 April 1915, the Allies made a dawn landing on the Gallipoli peninsula to overcome Ottoman land defenses. General Liman von Sanders, the German commander of the Ottoman armies, deputised local operations to a brilliant, ruthless young Turkish officer, Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk). ‘I am not ordering you to attack, I am ordering you to die,’ he proclaimed to his poorly equipped troops. And they did in droves during the first days of the campaign, halting the Allied advance inland and buying time for reinforcements to arrive. Some 46,000 Allied troops and 86,000 Turkish troops were killed, and hundreds of thousands more were injured on both sides, before the Allies withdrew in defeat late in 1915. Many of the Allied casualties came from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), and Anzac Day (25th April) is still commemorated locally by both countries.

Turkish War Memorial at Morto Bay

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

There are numerous guided tours of the peninsula from Çanakkale and Eceabat, or you can explore the region on your own. Much of the scenic peninsula is now a national park, rich in plant and bird life. A good general orientation is available at the moving Kabatepe Simulation Center, 9km northwest of Eceabat near the west coast (open 9.30-11am; 1.30-5pm; charge). Of the many well-tended cemeteries, cenotaphs and other memorial plaques that mark the former battlefields, the most famous are the Lone Pine Cemetery, the Nek and Anzac Cove, where Australian and New Zealand troops are buried, as well as Çonkbayırı, scene of the fiercest battles, Kemal’s most famous exploits and both Anzac and Turkish memorials. The British and French landings were in the far south at Cape Helles and Morto Bay respectively; tours tend not to visit these.

Side by side

There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us,

Where they lie side by side here in this country of ours…

You, the mothers who sent their sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears;

Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace after having lost their lives on this land

They have become our sons as well.’

Atatürk’s eulogy to the fallen at Gallipoli

Also on the peninsula, 50km (34 miles) from most of the battlefields, is the historic port town of Gelibolu where a Byzantine tower on the old port is home to Piri Reis Museum (daily except Thur 8.30am–noon, 1–5pm; free) dedicated to the great Ottoman cartographer (for more information, click here).

Çanakkale and Turkey’s Aegean islands

Ferries cross frequently between Eceabat or Kilitbahir and Çanakkale 2 [map], on the southeast shore of the Dardanelles. The largest town in the region and a good base for exploring, it has some reasonable hotels, a pleasant promenade with great views across the straits and a few seafood restaurants. About 1km (1⁄2 mile) from the centre, the 15th-century Ottoman fort is closed to the public, though next door a small Naval Museum features a replica of the mine-layer Nusrat which frustrated Allied naval attempts to run the Dardanelles (Tue–Wed, Fri–Sun 9am–noon, 1.30–5pm; charge; fortress grounds daily 9am–10pm in summer; 9am–5pm in winter). The Archaeology Museum (1.5km/1 mile south of the centre on the Troy road; daily summer 8am–6.45pm, winter 8am–5.30pm; charge) contains many local finds, in particular two intricately carved sarcophagi.

Çanakkale

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

From Çanakkale, Kabatepe dock or Geyikli İskelesi near Troy, car ferries or faster sea-buses make short trips to Gökçeada (İmroz) 3 [map] and Bozcaada (Tenedos), Turkey’s two largest Aegean islands. They each have volcanic origins, excellent south-coast beaches and a historically Greek-Orthodox population, but there the resemblance ends. Gökçeada is much bigger, with more dramatic scenery and a few hundred Greeks still living in the remotest villages; their summer festival, often lacking in Greece itself, when the island diaspora returns from Greece, İstanbul or even further afield to re-occupy ancestral homes. Public transport is sparse, so it’s definitely worth taking a rental car across. Bozcaada 4 [map] has an architecturally exquisite port town, a trendy İstanbul clientele which pushes prices up, and excellent wines from local vineyards. A superb castle (daily 10am–1pm & 2–6pm; charge) modified by every successive power in the Aegean guards the port. Less than twenty Greek Orthodox remain, and unlike on Gökçeada there are no priests, or religious services.

Troy

For centuries, people thought Homer’s stories of the siege of Troy 5 [map] and the voyages of Odysseus to be pure myth, but while the tales of gods and monsters can perhaps be taken with a pinch of salt, The Iliad and The Odyssey have some basis in fact. According to Homer, Paris, son of King Priam of Troy, kidnapped Helen, wife of King Menelaos of Sparta, the most beautiful woman in the world, and took her as his wife. Menelaos, his brother King Agamemnon, and an army of Greeks including the great heroes Achilles, Hector and Odysseus, set sail with an armada of 1,000 ships, laying siege to Troy for many years. Eventually they came up with the idea of a wooden horse left as a gift outside the gate. The overly trusting Trojans wheeled it into the city, but that night, Greek soldiers crept from its belly and opened the gates. And so the war was won, and the phrase ‘Beware of Greeks bearing gifts’ born.

Detail of the Temple of Athena, found in Troy

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

It was 1871 before German-American archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered the site that he claimed to be Troy, 32km (20 miles) south from Çanakkale (daily 8am–7pm in summer; 8am–5pm in winter; charge). It is a complicated place to visit, with at least nine city layers spanning some 4,000 years. . Schliemann’s greatest find, a large horde of gold, silver and copper treasure that he attributed to King Priam, was in fact nearly 1,000 years older. It vanished from Berlin in 1945, courtesy of the Red Army, and turned up in Moscow in 1993; it’s now in the Pushkin Museum, the focus of a three-way legal wrangle for ownership between Germany, Turkey and Russia. A new museum is under construction in Izmir to be completed in 2016.

Behramkale

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Behramkale (Assos)

Popular amongst İstanbul trendies long before Bozcaada, Behramkale 6 [map], on the Gulf of Edremit, 70km (40 miles) south of Troy, is one of the prettiest villages on the Turkish coast. With no beach and a protected architectural environment, its touristic development has been modest, confined to a handful of small hotels, some in converted acorn warehouses, both down at the tiny port and in the upper village some 240m (785ft) up the cliff. Upper Behramkale is dominated by the acropolis of ancient Assos (daily 8am–sunset; charge) with its stupendous views across to the Greek island of Lésvos, from where colonists founded the city in the 10th century BC. From 348 to 345BC, Aristotle lived here as the guest of ruler Hermias, while St Paul passed through in about AD55. Highlight of the acropolis is the 6th-century BC Temple of Athena, currently being restored with stone from the original quarries to replace the ill-advised concrete columns erected some decades ago. Other prominent remains include a particularly fine necropolis and about 3km (2 miles) of the old city walls, standing 14m (46ft) high in places.

Ayvalık

At the southern end of the Gulf of Edremit, 131km (81 miles) from Behramkale. Ayvalık 7 [map] (the ‘place of the quince’) grew up in the 18th century as a Greek Orthodox town, but was virtually abandoned after the 1923 exchange of populations. Subsequently repopulated by Muslim refugees from Crete, and Lésvos island opposite, it has grown massively but the centre still has a strong Greek flavour and immense charm, its fishing harbour overlooking a bay scattered with islets. The largest is Cunda (also called Alibey Adasi), with another well-preserved Greek settlement known by its founders as Moskhoníssi. Several of the Greek Orthodox churches have been converted into mosques. The area’s main beach resort lies several kilometres south, at Sarımsaklı, which has little charm, but does offer good sand and watersports. The area is a major producer of olive oil.

Old Mosque near Altinova, Ayvalik

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Pergamon

Head south south of Ayvalık on Route E87 for 54km (33 miles) to Pergamon 8 [map], once the most glamorous city in Asia Minor. Although originally founded in the 8th century BC, Pergamon reached its zenith during late Hellenistic and Roman times. One of Alexander the Great’s successors, Lysimakhos, entrusted a great treasure to his eunuch-steward Philetaeros. After Lysimakhos was killed in battle in 281BC, Philetaeros passed these riches on to his nephew Eumenes I, founder of the Pergamene dynasty, who used the fortune to begin a complete makeover of the city. By the second century BC Pergamon (also known as Pergamum), population 150,000, controlled almost half of Asia Minor. In 133BC, King Attalos III changed world history by bequeathing his vast territories to Rome.

Medicine at the Aesclepion

According to legend, Asklepios, the son of Apollo and the nymph Koronis, was taught medicine by the centaur Khiron and became the Greek god of healing, using the blood of the Gorgon to restore slain men to life. His emblem, a snake curled about a winged staff, is still the symbol of the medical profession. His temple and ‘wellness’ centre at Pergamon became one of the greatest therapeutic centres in the ancient world under the masterful tutelage of Galen (c.129–202 AD), considered to be the first great physician in Western history. Treatments included sleeping in the temple of Asklepios – after which the priests would interpret your dreams – colonic irrigation and walking through a tunnel while the doctor whispered a cure in your ear, but Galen was also the first to discover that arteries carried blood. His treatments were still standard practices 1,500 years later.

The city had all the usual trimmings, but also three truly outstanding features that made it famous throughout the ancient world. It was a notable religious centre, mixing worship of Zeus, the emperors and exotic Egyptian deities with that of the city’s patron goddess, Athena, and the normal Greek pantheon; it became a place of healing (for more information, click here); and it had a library fit to rival the Great Library at Alexandria. In fact, rivalry between the two was so intense that the Egyptians refused to let the Pergamene have papyrus, so its scribes revived the old technique of writing on treated animal skin (parchment) and binding it into codices. In its prime, the library contained some 200,000 volumes, but in 41BC Mark Anthony gave most of it to Cleopatra as a gift, perhaps to replace the thousands of scrolls that went up in flames when Julius Caesar inadvertently set fire to Alexandria in 48BC.

There are two distinct areas of ruins – the Acropolis (a long, steep climb from the modern town centre) and the Asklepion, about 8km (5 miles) apart by road; there is a taxi rank near the museum. Both sites are open daily 8.30am–5.30pm, until 6.30pm in summer (separate entrance charges).

Temple of Trajan and Hadrian

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The Asklepion visible today dates mostly from Emperor Hadrian’s reign (AD117–138), with two round temples to Asklepios and his son Telesphoros, healing springs, a theatre and a library. But most of the city is on the Acropolis, 300m (1,000ft) overhead with superb 360º views. Near the highest point stand the partially restored Corinthian columns of the 2nd-century AD Temple of Trajan and Hadrian and its stoa, just above the scantier remains of the Temple of Athena. The fabulously carved Altar of Zeus, with a frieze depicting the battle between gods and the Titans, was mostly taken to Germany during the 1880s and is now in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, along with much of the other choice relief art from the site. The Hellenistic theatre, dramatically built into the hillside, could hold 10,000. It originally had a removable wooden stage to allow access to a small Temple of Dionysos, though in Roman times a stone structure was built.

The Amphitheatre at Pergamon, with Bergama below

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Below, in the lively market town of Bergama with its old hill quarter, the Kızıl Avlu (Red Basilica, undergoing construction work at the time of writing but still worth seeing from outside; charge) was founded in the 2nd century AD as a temple to the Egyptian gods Serapis, Harpokrates and Isis, before being converted to a Christian basilica. Its pagan days are commemorated in Revelations 2:13, which cites Pergamon as where ‘Satan has his throne’, a clear reference to the still-thriving Egyptian cult. The Pergamon Arkeoloji Müsezi (Archaeological Museum; İzmir Caddesi; Tue–Sun 8.30am–noon, 1–5pm; charge) houses those finds not taken to Berlin, as well as artefacts from the dam-threatened archaeological site of Allianoi.

Çandarlı and Foça

With limited and mediocre accommodation at Bergama, the little resort and port of Çandarlı 9 [map] some 35km (22 miles) southwest makes a good potential base with its two beaches flanking a well-restored Genoese castle. Further along the coast, the Foça Peninsula is relatively undeveloped, with long stretches of militarily-protected coastline; the few public beaches tend to have stiff entry charges.

The town of Eski Foça ) [map] (Old Foça), the successor of ancient Phokaea, has a wonderful setting, another renovated Genoese fortress, and a number of restored Ottoman-Greek houses. It’s a popular retreat of people from Manisa and İzmir, and finding accommodation can be tricky on warm weekends.

Preparing fishing line in Foça

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The same cautions apply to nearby Yeni Foça (New Foça), with more well-restored old houses but an exposed beach. ‘Phokaea’ means ‘seal’ in ancient Greek, and a few Mediterranean monk seals still survive locally, although they are almost never seen.

The South Aegean

The South Aegean is much busier with foreign visitors than the North Aegean, with a longer season, warmer sea and an embarrassment of archaeological riches. There is also more choice in shops, restaurants and hotels.

İzmir

The third largest city in Turkey with a population of nearly 4 million, İzmir ! [map], formerly Smyrna, claims to be the birthplace of Homer (8th century BC), and there has been habitation here for over 5,000 years. But the city’s confirmed history starts in the 4th century BC when Hellenistic generals Lysimakhos and Antigonos built a fortified settlement. Set on a huge horseshoe bay, its superb harbour, a key outlet to the Mediterranean at the end of the Silk Road, ensured that İzmir prospered. Until World War I, it was a glamorous, cosmopolitan city, where Greeks and Latins far outnumbered Muslims, but that changed during the last days of the bitter War of Independence. As the Greek army retreated in disorder and thousands of refugees converged on the docks hoping for a ship out, Smyrna fell on 9 September 1922 to Atatürk’s forces, who engaged in the traditional three days of plunder and murder before setting 70 percent of the city on fire.

İzmir’s seafront clock tower

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

İzmir eventually recovered, and the seafront promenade is lined with a combination of palms, cafés and a few opulent mansions in Pounda district that survived the blaze. The pivotal Konak Meydanı sports a pretty little mosque, the Konak Camii A [map] (1748), the Saat Kulesi, a decorative clock tower built in 1901 donated by Sultan Abdül Hamit, and a monument dedicated to the first Turkish soldier to lose his life during the Greek invasion of 1919. To the south, in Turgutreis Parkı, are the city’s Archaeological and Ethnographic Museums (both Tue–Sun 8.30am–5pm; charge). The Arkeoloji Müzezi B [map] has an impressive collection of finds from nearby sites, including some fine Classical statuary, while the Etnografya Müzesi C [map], housed in a restored late-Ottoman hospital, has interesting photos and reconstructed buildings showing what the city was like pre-1922. Walk through the back streets from here and you find yourself in the Kemeraltı bazaar D [map], a gloriously eclectic mix of everything from leather jackets to live chickens. Behind this, at the foot of the castle, lies the Roman Agora E [map] (daily 8.30am–noon, 1–5pm; charge), rebuilt by Marcus Aurelius after an earthquake in AD178.

Kemeraltı Bazaar

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The best views of the city are from above. Climb (or take a taxi) up to Kadifekale F [map] (Velvet Fortress), first built by Alexander’s successors but rebuilt and used by everyone since; its final ruined incarnation is a 500-year-old Ottoman fortress. To the north, you will notice the Kültür Parkı, the city’s main open space but also home to tea gardens and the İzmir Tarih ve Sanat Müzesi G [map] (History and Art Museum; Tue–Sun 8.30am–noon & 1–5.30pm; charge), a fascinating museum that includes a sumptuous collection of Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine jewellery, along with statuary and ceramics from the 6th century BC to the Ottoman period. Just to the south of the park, the Ahmet Piriştina Museum of Metropolitan History and Archive H [map] (Mon–Sat 8.30am–5.30pm; free) is a converted fire station, charting the city’s history, with special reference to its fires.

Blue Cruising

There can be few things more perfect than drifting gently along one of the world’s most beautiful coasts in a traditional wooden gulet, stopping to swim or dive off where you choose, sunbathe in deserted coves, or snorkel above ancient ruins toppled by an earthquake into the sea. And all this can be yours on one of Turkey’s famous blue cruises. Whether you choose to go for a day or several, join a tour or hire a whole boat for your own party – the options are limitless and the prices (in spring or autumn) very affordable. Do your homework. A gulet traditionally sleeps between 8 and 14 people although they can be larger; is propelled largely by motor (sails are usually decorative); and comes with both sail and motor; and comes fully equipped and staffed. If you have your own boat, you can set your own itinerary, eat on board, have barbecues on the beach or berth in town for a night on the tiles, as you prefer. Many tour operators offer this as an option (for more information, click here) or you can wander along any harbour and see if you can do a deal locally, although this is obviously more fraught with difficulties.

To round off the day, take the brick Asansör I [map] (Elevator; 7am–late; free), built in 1907 by a wealthy Jewish businessman, up to the old Karataş district, historically the Jewish quarter, where you can have a drink, a meal (for more information, click here) and watch the sun set over the bay.

Çeşme Peninsula

Pushing west into the Aegean from İzmir, the Çeşme Peninsula is a holiday playground for wealthy city-dwellers and savvy foreigners, with a perfect blend of great beaches, equable summer weather and natural hot springs that have spawned some ravishingly good spas.

Çeşme Peninsula

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Located some 75km (47 miles) west of İzmir on the O-30 motorway, Çeşme @ [map] (whose name means ‘wall fountain’) is a pretty town with a 14th-century Genoese Castle of St Peter (daily 8.30am–7pm, until 5pm winter; charge) with displays of sculpture, coins and artefacts from nearby Ildırı (Erythrai) and a 16th-century kervansaray, built during Süleyman the Magnificent’s reign and now once again a hotel. A recently opened marina is bidding to catapult Çeşme into the big leagues from its rather sleepy past.

Popular resorts on the surrounding peninsula include Dalyan (5km/3 miles north of Çeşme), with more yacht anchorage and famous fish restaurants; Ilıca (5km/3 miles east of Çeşme), which has hot springs offering therapeutic treatments as well as several excellent spa hotels; and Alaçatı (9km/5 miles away), a lovingly preserved former Greek village noted for its great wind- and kite-surfing, trendy nightlife and boutique hotels. The best beaches are to be found at Altınkum, 9km (6 miles) southwest of town, a series of sandy coves protected from over-development by the forest service.

Sardis gymnasium

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Sardis (Sart)

Detour inland for 100km (60 miles) on route E96 from İzmir to visit Sardis £ [map] (daily 8am–7pm, closes 5pm winter; charge), once the richest city in Asia Minor. The capital of ancient Lydia, it lay at the junction of the roads between Ephesus, Pergamon and the east, and the Lydians profited from every passing traveller. Not only that – the mountain overhead was rich in gold. In the 6th century BC, the last of the Lydian kings, Kroisos (Croesus), invented coins and dice but his conspicuous wealth attracted unwanted attention from the Persians. Kroisos consulted the Delphic Oracle which replied that if he attacked the Persian king, Cyrus the Great, a great empire would fall. Kroisos went ahead, but unfortunately the kingdom destroyed was his own. Amongst the many ruins, highlights include the vast Temple of Artemis, begun in the 4th century BC but tumbled by an earthquake in AD17 before it was completed; the beautifully restored Marble Court of the 3rd-century AD gymnasium; and the impressive, reconstructed synagogue, the largest ancient synagogue outside of Palestine, evidence of the sizeable, prosperous Jewish community in Roman Sardis.

Selçuk

Although first settled almost 4,000 years ago, Selçuk $ [map] only really began to grow after the harbour of nearby Ephesus finally silted up in the 5th century AD. These days it is a small provincial town with a few interesting sites. The Selçuk Museum (main through road; daily 8.30am–5pm, until 6.30pm in summer; charge) is home to many of the finds from Ephesus and other nearby sites, including sumptuous statues of the ‘many-breasted’ Artemis and a playful bronze statuette of Eros riding a dolphin.

On Ayasoluk Hill, above the town, is an ancient citadel. It was here, in about AD100, that St John the Evangelist, one of Christ’s twelve apostles, supposedly died and was buried. In the 6th century AD, Emperor Justinian built a magnificent basilica around his tomb (daily 8am–5pm, until 6.30pm summer; charge). This was destroyed by the Mongols in 1402, but the place is still an important Christian pilgrimage site. At the foot of the hill is the ornate, late 14th-century İsa Bey Mosque (daily 9am–6pm).

On the way out of town, heading towards Ephesus, pause briefly next to a few bits of fallen marble and one column, all that remain of the once-glorious Temple of Artemis (daily 8.30am–5.30pm; free), once considered among the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. First built in the 7th century BC to honour Cybele, burnt in 356 BC by a lunatic, rebuilt by Alexander’s successors and sacked by the Goths in AD263, its masonry was eventually plundered by Justinian for recycling in İstanbul’s Aya Sofya and Selçuk’s St John’s Basilica.

Ephesus

In Roman times, Ephesus % [map] (3km/2 miles west of Selçuk; daily 8.30am–6.30pm, closes 4pm in winter; charge) was the jewel of the Aegean coast. A dazzling city founded by Athenian settlers in about 1000BC, it thrived on the profits from its harbour, only eventually withering when its harbour silted up in the 5th century AD; it now lies several kilometres inland. St Paul lived and preached here in AD52, and later wrote one of his New Testament epistles to the Ephesians.

Deliverance

During persecutions under Roman Emperor Decius (r. 249–51 AD), seven Christians took refuge in a cave a few hundred metres east of Ephesus and fell asleep. When they woke up and returned to town, they found that 200 years had passed, Christianity had become the state religion and they were safe.

Ephesus theatre, at the end of the Arcadian Way

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The site is extensive, extraordinarily well preserved and well restored. To do things the easy way, take a taxi from the main car park at the bottom to the Magnesian Gate and East Gymnasium at the top of the site and walk downhill along the Street of Curetes past the Upper Agora, Trajan’s Fountain and the Odeon, a ‘studio’ theatre for concerts and poetry. The small 2nd-century AD Temple of Hadrian with an ornate façade is further down on the right, with the Baths of Scholastica behind it – look out for the communal toilets and beautifully draped, headless statue of the bath’s benefactor. Opposite are a large mosaic and steps leading up to the late Roman and early Byzantine terrace houses (daily 8am–6pm, closes 5pm winter; separate charge) decorated with frescoes and mosaics.

On the corner with Marble Avenue, the city’s brothel is signed by a footprint in the stone. Inside, rooms surrounding the central atrium have decoration that suit the purpose while in the main reception area is a mosaic of the Four Seasons. Just off Marble Avenue, on the left, the superbly restored Library of Celsus was built early in the 2nd century AD by the Roman Consul Gaius Julius Aquila and destroyed by Goths in AD 262. Between times, it housed some 12,000 scrolls.

Library of Celsus detail

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Further on, the 24,000-seat theatre stands at one end of the Arcadian Way, the colonnaded main street down to the harbour. It was so sophisticated that by the 5th century AD, its covered walkways had street lamps at night (along with only Rome and Antioch). Just north of the Arcadian Way stand the huge 2nd-century AD Harbour Baths and Gymnasium and the Church of the Virgin Mary, the first ever dedicated to the Virgin, converted from a Roman warehouse. On the far side of Marble Avenue are sparse remains of the stadium and the Vedius Gymnasium.

Camel wrestling

One of the hottest spectator sports in the southern Aegean is camel-wrestling, with a circuit of about 30 festivals, and some 100 camels competing at any given time. Based on the mating-season rituals of wild camels, individual matches last 10 minutes, with a huge amount of surrounding razzmatazz. The season lasts from December to February.

An old legend claimed that the Virgin Mary came to Ephesus with St John and lived her last days here. In the early 19th century, a German nun, Catherine Emmerich, had a vision of her house and in 1891, some Lazarist monks found a house that matched. In 1967, Pope Paul VI arrived and declared it authentic. Today, the Meryemana (Virgin Mary’s House; 5km (3 miles) south of Ephesus; 7.30am–sunset; charge) is a major pilgrimage site, with religious services on 15 August and the first Sunday of October.

Kuşadası

About 20km (12 miles) southwest of Selçuk, Kuşadası ^ [map] is the most popular resort in the South Aegean, with a crowded marina as well as a busy cruise terminal, plus plenty of shops, restaurants and bars. The only sights are the 14th-century Genoese castle on Güvercin Adası (Pigeon Island), with snack-bars and tea gardens inside, and the 16th-century Kervansaray by the harbour, now back in service as a hotel. There are no beaches in town, but there are several nearby: the best are Tusan and Pamucak, a few kilometres north.

Just 33km (20 miles) to the south, the Dilek Yarımadası Milli Parkı & [map] (daily summer 8am–6.30pm, must exit 7pm, winter 8am-5pm; charge) is a stunningly beautiful 27,000-ha (66,700-acre) national park encompassing Samsun Daği (the ancient Mt Mykale), with fine beaches, woodlands, and wildlife including jackals, boar and badgers.

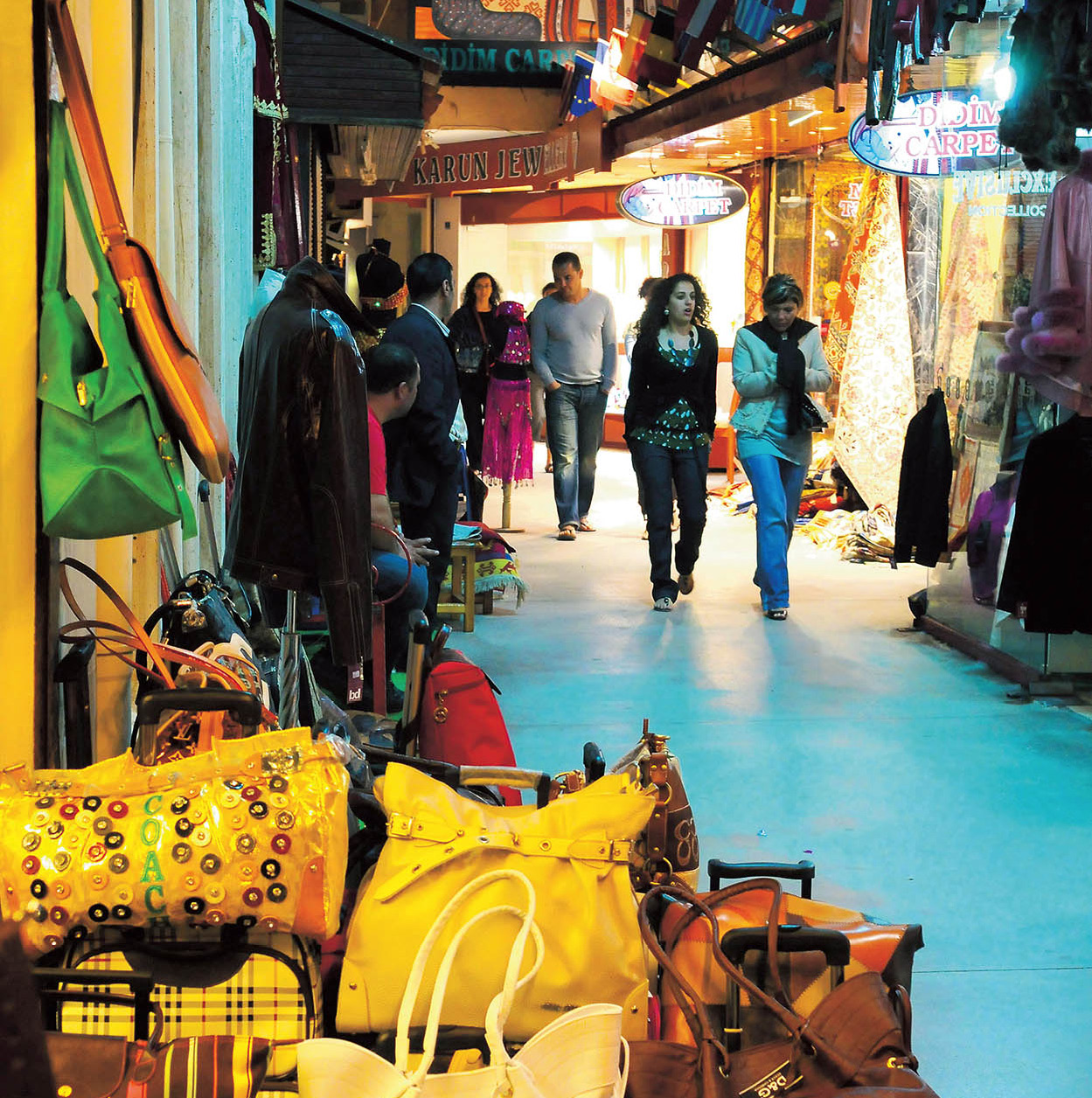

Shopping in Kuşadası

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Steam buffs may want to take a detour a short distance inland to the Çamlık Buharlı Lokomotif Müzesi (Steam Locomotive Museum; daily 8.30am–5.30pm; charge), home to some 25 pre-World War II trains from all over Europe.

Priene, Miletus and Didyma

On the south flanks of Samsun Dağı, 37km (23 miles) from Kuşadası, Priene * [map] (daily 8.30am–6.30pm, closes 5.30pm winter; charge) has one of the finest settings of any ancient city in Anatolia, on a series of pine-clad terraces backed by huge cliffs with views across the flood-plain of the Menderes River. Moved here from elsewhere in the region during the 5th century BC, Priene was still one of the first local cities to have its port silt up, before the Romans arrived, so the architecture and layout retains its Ionian/Hellenistic purity. There is a marked route through the grid of streets, past houses and shops, council buildings, the agora, Temple of Zeus and Temple of Athena (designed by Pytheos, architect of Bodrum’s Mausoleum, for more information, click here), the theatre and the Sanctuary of Demeter.

Carry on south for another 22km (14 miles) and you reach the next of the great city-states that once traded along this coast, Miletus ( [map] (Milet; Tue–Sun 8.30am–5.30pm, until 7pm in summer; charge). Settled by a mythical son of King Kodros in the 10th century BC, it became hugely rich, with colonies in Egypt and the south of France, and was the birthplace of Thales, considered to be the first of the great Greek philosophers and astronomer-mathematicians in the 6th century BC, noted for his advocacy of scientific rather than mythological explanations of natural phenomena. Relatively little of the city remains, but the huge theatre, with seating for 25,000, is in astonishing condition.

Miletus’ amphitheatre

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Nearby Didyma , [map] (Didim; 15km/9 miles further along the same road; daily summer 9am–7.30pm, winter 8am–5.30; charge) is best visited towards sunset when the light glows through the columns of its superb Temple of Apollo, home to one of the great oracles of the ancient world, second in importance only to Delphi. Work on this vast marble temple went on for a full 800 years after Alexander the Great sponsored its reconstruction (it had been destroyed by the Persians), but it was never completed. Now the whole of the surrounding area, especially the beach town of Altınkum 5km (3 miles) south, has been overwhelmed by building work as developers cash in on the desire of northern Europeans to own a little piece of sunshine.

Excursions to Aphrodisias and Pamukkale

Priene and Miletus originally stood well to seaward of the advancing delta of the Menderes River, known in Classical times as the Maeander (giving us the verb we still use today). Follow it inland along Route E87 to Aphrodisias ⁄ [map] (80km/50 miles from the coast; daily summer 9am–6.30pm, closes 5.30pm winter; charge), a vast city devoted in antiquity to marble sculpture and the love goddess. Most of the ruins date from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD and include a magnificent theatre, 30,000-seat stadium – one of the best preserved in Anatolia – the Tetrapylon (quadruple gateway) and colonnades of the Temple of Aphrodite, later converted into a Christian basilica. The site museum (may close Mon) features abundant local sculpture.

A frieze block in Aphrodisias

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

A further 90km (56 miles) northeast by roundabout roads lies one of the world’s most stunning geological formations, the so-called ‘Cotton Castle’ at Pamukkale ¤ [map] (24hr; charge during daylight hours), an extraordinary solidified cascade of travertine formed by mineral-rich hot springs, its chalk-white basins and pool water glimmering and changing with the light. There is a village, Pamukkale Köyü, at the base of the travertines, but atop the plateau you will also find the huge ruined city of Hierapolis, founded by Eumenes II of Pergamon, which grew rich from the wool trade and as a spa. It had a large large Jewish and later Christian community but was virtually destroyed during the Arab invasions of the 7th century. Prominently on view are a fine Roman theatre, still used for performances, and a huge necropolis, where the most sumptuous tomb belonged to one Flavius Zeuxis.

Pammukkale

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Only one of several paths can be used at any given time to traverse the deilciate travertine terraces, to protect them from erosion, but take your swimming costume along so you can have a dip in the Antique Pool (daily 8am–7pm; charge), the once-sacred bathing area of the spa (said to be good for arthritic complaints). Most of the larger tourist hotels and many other spas are a few kilometres away in the village of Karakhayıt.

The Turquoise Coast

Bodrum

A playground for Turks and foreigners alike, this southwestern corner of Anatolia, where the Aegean and the Mediterranean meet, has relatively little in the way of high culture and ancient artefacts but compensates with stunning scenery, fabulous beaches, sybaritic resorts and clear blue waters that delight yachties, divers and windsurfers.

Party central is Bodrum ‹ [map], 125km (78 miles) southeast of Didyma. Bodrum’s name means ‘cellar’ or ‘dungeon’ and it was used as a place of exile by both the Ottomans and republican Turkey; these days, it one of the most liberal and gay-friendly towns in Turkey, sophisticated and worldy enough to seem a transplanted piece of the French Riviera. Architectural rules have kept the town fairly small and low-slung, its houses piled around its two bays like sugar cubes. If you book a hotel here, you may well be staying in one of a dozen resort villages that encircle the indented Bodrum pensinsula, 40 minutes’ drive distant, as there are relatively few big hotels in Bodrum proper.

Herodotus

Named the ‘Father of History’ by Cicero and, less flatteringly, the ‘Father of Lies’ by his detractors, Herodotus lived in Halikarnassos (modern Bodrum) from c.484–425BC. He was the first person known to collect, collate and publish his material systematically and objectively, publishing The Histories in nine volumes: a chronicle of the 5th-century Persian Wars, along with a wealth of strange travellers’ tales reported by returning sailors.

Founded in the 12th century BC as Halikarnassos, in the 4th century BC it was ruled by King Mausolus of the Carians, whose sister/wife, Artemesia II, built him a tomb so grand that the Mausoleum (Tue–Sun 9am–5pm; charge) became one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world and the prototype for all other mauseolea. It stood nearly 50m (160ft) high, with 250,000 stones and surrounded by grand friezes, but only fragments of it now remain, and most of the best reliefs are in the British Museum. Just to the north is the ancient theatre (Tue–Sun 8.30am–5.30pm; charge), recently restored and back in use for the September festival. Once seating more than 13,000, most of it was destroyed by an earthquake, with the masonry (like that of the Mausoleum) re-used to build the castle, and the new version has a cosier capacity of 1,000.

Bodrum’s castle casting reflections

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The Castle of St Peter (Tue–Sun 8.30am–5.30pm, summer until 6.30pm, but different opening times for the separate exhibits inside; charge), built in the 15th century by the Knights of St John, is a magnificent fortress that was for 70 years until 1522 a lone, heavily fortified outpost of militant Christianity in Anatolia. It is now home to a world-class Museum of Underwater Archaeology, whose treasures include a 14th-century BC shipwreck in the Uluburun Wreck Hall, an 11th-century AD Byzantine ship and its cargo in the Glass Wreck Hall, and the richly endowed tomb of a Carian princess, whom some say might have been the last Carian queen Ada, dating to about 330 BC.

Bodrum Peninsula Resorts

An ever-expanding ribbon of hotels, apartments and villas envelop the peninsula that stretches out southwest and northwest of Bodrum, but the different resorts do have distinct identities. Gümbet is popular with party-loving youngsters from the UK, while Bitez next along attracts an older crowd and watersports enthusiasts. Karaincir further west has one of the best beaches, while neighbouring Akyarlar is famous for its fish tavernas. Gumuşluk, atop ancient Myndos, combines posh with Turkish-bohemian and a decent beach, while Yalıkavak is more middle of the road. Türkbükü is very trendy, very expensive and mostly Turk-patronised, Gölköy is slightly ‘alternative’, while Turgutreis is by contrast the busiest, most mass-market centre.

Looking towards Myndus from Gumuşluk

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The Road to Marmaris

As the fish swims, Marmaris isn’t that far, but by land it takes a few hours to twist around the eminently scenic, statutorily protected Gulf of Gökova, with the highway passing small roadside stalls selling forest honey and olive oil.

Stop for a look at Milas, beyond Bodrum’s airport, home to a distinctive style of carpet, some fine old Ottoman architecture and an excellent Tuesday market; and Muğla, the local provincial capital, its back streets filled with centuries-old Ottoman houses, the narrow lanes of its bazaar still divided by trade.

Marmaris and Around

In 1522, Süleyman the Magnificent anchored the entire Turkish fleet in Marmaris › [map] harbour prior to besieging Rhodes, and in 1798 Lord Nelson rested the whole British fleet here en route to Egypt to defeat Napoleon’s armada at the Battle of the Nile. The deep inlet still offers some of the best anchorage on the coast, and is home to Turkey’s largest marina. Marmaris has a small castle near the bazaar (ideal for souvenir shopping), built originally by the Knights of St John, taken over by the Ottomans and now housing a small museum (Tue–Sun 8.30am–noon, 1–5pm; charge). On the main road 9km (6 miles) before Marmaris is a superior, private archaeology and ethnography museum, the Halıcı Ahmet Urkay Müzesi (Tue-Sun 9am–6pm; charge), complete with carpet and craft shops.

Marmaris

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

But most people come to Marmaris for the sun, sea, watersports and nightlife, the latter found in the town centre ‘Bar Street’, or in the resort hotels and clubs that stretch out along the beaches of Içmeler and Turunç around the bay. Those looking for more peace and quiet head further southwest onto the remote Bozburun Peninsula where wonderful little boutique hotels and small villages are relatively undiscovered amidst wild mountains and increasingly narrow (though mostly paved) roads.

Out on its own peninsula, 70km (43 miles) from Marmaris, Datça, once just a market town and local port, has become a minor resort and real-estate centre. To the west – reachable by excursion boat from Datça as well as by land – lie the region’s most idyllic beaches, at Hayit Bükü, Ova Bükü and Palamut Bükü. Beyond the latter awaits the area’s only major archaeological site, partly excavated ancient Knidos fi [map], formerly home to a famous Aphrodite shrine. Of this little remains; content yourself instead with a fine theatre and two Byzantine basilicas, one preserving mosaics.

Knidos

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Dalyan

From Marmaris, Highway 400 leads north, then east most of the 88km (54 miles) to Dalyan fl [map], the next resort of note. This quiet little town lies on a reed-lined river, the Dalyan Cayı, partway between Lake Köyceğiz and the sea. There are no sites within the town itself, although there are fine views of some 4th-century BC Lycian-style rock tombs in the cliff opposite. Most activities involve long, leisurely trips on the river in one of the many boats that vie for your custom along the central quays.

Upstream Lake Köyceğiz is open brackish water fringed in parts by reed beds where storks and herons fish. Up to 180 species of birds can be seen here seasonally when migrants stop to join the local residents, and there are plenty of butterflies, dragonflies and other wildlife including fish (dalyan means fishing weir), including excellent gilthead bream and sea bass which end up on restaurant plates. On the lake’s south shore, are mineral-rich thermal springs at Sultaniye and mud baths at Ilıca closer to Dalyan, claimed therapeutic for a raft of nervous, digestive, dermatological and sexual disorders. After coating yourself in mud or wallowing in a 40ºC domed pool, you are more than ready for the next part of the day.

Downstream, the river twists its way towards the sea, past the ruins of ancient Kaunos (daily dawn to dusk; charge), first settled by the Carians of Halikarnassos in the 9th century BC. Various cultures controlled it over the centuries, leaving their monumental mark, from imposing Lycian-style rock tombs, to Hellenistic walls and a theatre, Roman baths and a Byzantine basilica. Signposting and weeding have improved greatly in recent years, making the site increasingly rewarding.

Sea Turtles

Loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) mate in the open sea during the spring migration. The huge females, who can weigh up to 180kg (400lb) and measure up to 1m (3ft) long, haul themselves ashore at one of the17 Turkish where they themselves were born, between May and September, to lay clutches of up to 100 leathery ping-pong ball-sized eggs in the hot sand. These take seven weeks to hatch – assuming foxes do not dig them up – with the hatchlings cued to head for the water by moon- or star-light glinting on the waves. Thus, hotel and bar lights, or even torches, can disorientate them and lure them inland to die. These days, most turtle beaches are off-limits at night during breeding season, and you may see markers guarding the nests to stop you spearing them with beach umbrellas.

If they make it to adulthood (unlikely for many, as threats abound at sea as well) a loggerhead will usually live well past 50 years and can reach 70 years of age. They are mainly carnivorous, living on small fish, jellyfish and other marine invertebrates.

River-boat trips (and a more roundabout road for drivers) both end at İstuzu Beach (charge for all arrivals), a superb 3.5km (2.5-mile) long sandbar that fringes the vast wetlands behind, shared by happy sunbathers during the day and loggerhead turtles (for more information, click here) who heave themselves ashore by night to lay their eggs. There are strict laws protecting the nests and the beach is closed at night during nesting season.

The Lycian Coast

From Dalyan, the main highway runs southeast to Fethiye for nearly 70km (43 miles) with relatively little to excite the visitor other than the turnings for Sarıgerme beach and yachting-friendly, largely beach-free resort of Göcek. This all changes as you enter ancient Lycia (Likya in Turkish), with its rugged mountain soaring to over 3000m (9750 ft) elevation at two points, with only one major river valley to interrupt their climb from the sea. Until the late 1970s there was no continuous paved road through here, and most coastal settlements were easiest reached by sea. Such logistics are now history but this is still probably the most spectacularly beautiful area of the Turkish coast as well as one of the richest in history.

The Lycian coast

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Fethiye

Lycia’s main market and real-estate town, Fethiye ‡ [map] expands continually northeast along the coastal plain. The town, previously called Meğri or Makri, was renamed Fethiye during the 1930s, in honour of a World War I Ottoman pilot, Fethi Bey, who crashed in the Syrian desert. It was devasted by an earthquake in 1857, and after another earthquake in 1957 much of it had to be rebuilt. However, there are some fine Lycian rock tombs in the cliff above town, in particular the 4th-century BC Tomb of Amyntas (take the steps from Kaya Caddesi, behind the bus station; daily 8.30am– sunset; charge) and several free-standing tombs scattered round the town – most of what remains of ancient Telmessos. It also has a partly excavated Hellenistic theatre and a newly revamped museum (off Atatürk Caddesi; Tue–Sun 8.30am–noon & 1–5pm; charge) filled with finds from the nearby sites. A ruined castle with contributions from many eras looms overhead, and there is an Ottoman hamam (Turkish bath) in the bazaar district, a perfect place to clean off the dust of the day (for more information, click here). There are plenty of boat trips available from the bustling harbour front; there is also a great market on Tuesday. The nearest (gravelly) beaches are in Çalış, which also has a waterpark, Sultan’s Aquacity (www.sultansaquacity.com).

The closest Lycian site to Fethiye is Kadyanda ° [map] (24hr; charge if warden present), 20km (12 miles) northwest on a gorgeous forested mountaintop above Üzümlü village. A loop path with signage provides a 45-minute, self-guided tour around the partly excavated city; it passes substantial chunks of city wall, a stadium with seven rows of seats, a Roman-era baths, and the theatre.

Beach clubs

There are relatively few big beaches along this stretch of coast and many of the small inlets and coves are hard to get to. If you are not staying at a resort hotel with bathing platforms you may like to check out one of the beach clubs – a place to swim and sunbathe by day, with swimming platforms, pools, sunbeds, drinks and snacks, transforming into restaurants and dance clubs by night.

Ölüdeniz and Around

The real tourism hotspot of the region is about 12km (7 miles) south of Fethiye, centred on Ölüdeniz · [map] lagoon, the beach that features in almost every poster promoting the Turkish coast. It is picture-book perfect, an indigo oval fringed by white sand and backed by soaring mountains clad in pine forests. The immediate environs of the lagoon has been declared a national park and is protected from development, but this is a very small area; the whole valley descending to adjacent Belceğiz beach is crammed full with hotels and apartments. At the top of the slope, the nearly merged inland resorts of Ovacık and Hisarönu has grown up to service a decidedly mass market and predominantly British tourist trade.

There is a wide range of watersports available off Belceğiz beach, and Baba Dağı looming overhead is Turkey’s best venue for paragliding (for more information, click here). The most popular sedate excursion is the short boat trip across to Kelebek Vadisi (Butterfly Valley), a steep-sided flat-bottomed valley with a waterfall inland. Some 30 species of butterfly and 40 species of moth find their way here in season (June–Sept). The properly shod and non-acrophobic can hike up and out of the valley to Faralya village up on a palisade, effectively the start of the five-week-long Lycian Way long-distance trail to Antalya (for more information, click here).

The Lycian rock tombs

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Another local attraction is the enormous ghost town of Kaya Köyü º [map], the largest in Asia Minor, about 5km (3 miles) northwest of Ölüdeniz. Originally Karmylassos in antiquity, this was the 3000-strong Greek village of Levissi, with three large churches, until the 1923 exchange of populations. The incoming Macedonian Muslims for the most part declined to stay, considering the land on the adjoining plateau poor in comparison to what they had left. So the 600 hillside houses were mostly never re-occupied; a preservation order has been applied to the entire area, and many Greek-Turkish reconciliation events have taken place here.

The Goddess of Lycia

In legend, Leto was a nymph who, like so many before her, caught the eye of Zeus, ended up pregnant and fled from the wrath of his jealous wife, Hera. Arriving near the ancient Xanthos River, she was befriended by wolves (lykoi in Greek, conveniently, though Lycia is probably a corruption of the Hittite Lukka) who led her to the river to drink, before giving birth. Leto and her children became the presiding deities of Lycian culture, but not before the goddess had her revenge on two spiteful shepherds who had driven her away from a spring, by turning them into frogs – the ancestors perhaps of the large number of amphibians who inhabit the submerged nymphaeion today.

Eşen Valley

East of Fethiye, the coast protrudes south in a fat mountainous bulge. The faster Highway 350 east cuts inland to Antalya, while the far more scenic coastal road turns south at Kemer to follow the Eşen Çayı. Sites of interest line both sides of the river valley and you need two days to visit them all. Tlos, Saklıkent and Xanthos lie on the east bank; Pinara and Letoön are to the west. The new main coastal road is busy, but the old parallel roads are ideal for cyclists in spring or autumn.

Tlos ¡ [map] (36km/22 miles east of Fethiye; 24hr; charge when warden present) was mentioned by the Hittites in the 14th century BC, and its citadel was still inhabited by a notorious brigand, Kanlı Ali (Bloody Ali) during the 19th century. The Roman-Byzantine city spreads below, its highlights including the apsidal hall of the Yedi Kapı baths overlooking the valley, and the imposing theatre with the Akdağ range as a backdrop.

Saklıkent Gorge

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Follow the secondary road from here through to Saklıkent Gorge ™ [map] (daily dawn to dusk; charge; parking charge). Some 300m (1,000ft) high and 18km (12 miles) long, this narrow canyon in the Akdağ mountains is the longest gorge in Turkey. As you approach, the road is lined with platform-restaurants overhanging the river rushing from the gorge; that is the main reason people come here – to escape the heat of the coast, have a paddle or a swim in the cold mountain water and eat trout. A prepared catwalk, and then a rocky trail (often under water) permit visitors to safely explore the lower 2km of the canyon.

The back road carries on through to Xanthos # [map] (1km/ 1⁄2 mile from Kınık town; daily 8am–7.30pm in summer, closes 5pm in winter; charge). This was the notional capital of the Lycian Federation, famed for its fierce pride and independence. Twice, in 540BC when besieged by the Persian general Harpagos, and again in 42BC, when attacked by Roman legions led by Brutus, the Xanthians chose to commit mass suicide rather than surrender, the warriors making a funeral pyre for the families before heading out for a final hopeless battle. Each time, sufficient numbers appear to have survived for it to have been rebuilt, as it has a large number and variety of ruins, from a Roman theatre and mosaic-decorated Byzantine basilica to numerous fine tombs. In 1842, British archaeological scavenger Sir Charles Fellows loaded many of the finest friezes, including the originals from the 5th-century BC Harpy Tomb and the Ionic temple known as the Nereid Monument, onto the HMS Beacon (with the Sultan’s permission) for shipment to the British Museum.

Across the valley from Xanthos, the Letoön ¢ [map] (daily 8am– 7.30pm in summer, 8.30am–5pm in winter; charge), founded in the 7th century BC, was never a city but a religious sanctuary dedicated to the goddess Leto and her twin children, Artemis and Apollo. There are three temples on the site spanning several centuries, one, dedicated to Leto, one to Apollo and one to Artemis; a French archaeological team has partially re-erected the Leto temple. The northeast entrance of the Hellenistic theatre has 16 relief masks, and a tomb with a carving of the toga-clad deceased.

Letoön

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Some 21km (13 miles) north, Pınara (24 hr; charge when warden present) is the least visited but among the most beautifully set of the valley sites. Most of the city is an unexcavated jumble under pines, except for the remote theatre and a fine tomb by the seasonal stream, with a carved skyline of a town and above this a relief carving of people and animals in procession.

Horse riding on Patara’s sand dunes

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Patara

The oracle of Apollo once worked at Patara ∞ [map] (12km/8 miles south of Xanthos; daily dawn–dusk; charge) although his temple has not yet been found amidst the dense vegetation and sand dunes here. Sun worship of a different sort is the main activity these days – Patara has one of Turkey’s finest beaches, a blindingly white 15km (10-mile) long stretch of sand that has been saved from development by the presence of two ancient sites (the other being Pydnae, the port of Xanthos and the Letoön, at the far end) and turtle-nesting grounds, forcing the hotels inland to Gelemiş village. There are municipally run sunbeds and a reasonable snack bar only at the Gelemiş end. In the village, horse-riding and canoeing on the Eşen Çayı can be arranged.

Patara was the key port of the Lycian Federation, and attracted many visitors over the years, from Alexander to Brutus, while St Nicholas was born here. The site, where proper excavations have only resumed since the millennium, is slowly revealing its charms: a partly submerged agora with colonnades, a bath similar to that at Tlos, a largely intact theatre cleared of drifting sand, and a fine bouleuterion (council house) where Lycian Federation representatives deliberated.

Baba Noël (Father Christmas)

Born in Patara in about AD270, Nicholas became Bishop of Myra, and was persecuted by Diocletian before attending Constantine’s first ecumenical council at Nicaea in AD325. He is said to have saved the three daughters of a poor merchant from prostitution by anonymously tossing purses of gold coins through their window to serve as dowry. By his death in 343, his deeds ensured him a place as one of the busiest of saints, as patron saint of prisoners, sailors, travellers, unmarried girls, pawnbrokers, merchants, children, bankers, scholars, orphans, labourers, travellers, judges, paupers, victims of judicial mistakes, captives, perfumers, thieves and murderers along with many countries and cities, chief amongst them Russia and Greece. But his biggest role was yet to come, in the transformation of the 4th-century St Nicholas to Santa Claus to Father Christmas (his jolly red uniform and long white beard added by the Coca-Cola company in the 1930s to match their logo). His feast day is 6 December, when special services are held at Demre (for more information, click here).

Kalkan

Thirteen kilometres (8 miles) east of Patara, an improved road glides down to Kalkan § [map]. Formerly Greek-Orthodox-inhabited Kalamaki, the post-1923 village survived from fishing, charcoal-burning and olives until the late 1970s. After a period as a bohemian retreat, Kalkan has gone decidedly upmarket, and middle-aged ex-pat, with second homes now greatly outnumbering casual accommodation. Its old centre is still attractive, with pastel-shaded old buildings climbing the slope from the yacht harbour and small pebble beach. The sea is kept clean and bracing by numerous fresh-water seeps; many visitors swim from lidos flanking the sides of the bay. The nearest sandy beach is 6km (4 miles) east at Kaputaş, a tiny cove at the mouth of a deep gorge, reached by a long flight of steep steps off the main road. Escape the local summer heat here with a trip 8km (5 miles) inland and uphill to İslamlar (Bodamya) with its greenery and trout restaurants.

Old house in Kalkan

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Kaş

Kaputaş is en route to Kaş ¶ [map], 30km (18 miles) east of Kalkan, the main town on the south Lycian coast. This began life as the Hellenistic port of Antiphellos, exporting timber and sponges, morphing eventually into the Greek Orthodox settlement of Andifli. Unlike Kalkan it attracts a broader spectrum of both Turkish and foreign holiday-makers, with good shops along its Uzun Çarşı, good restaurants and a lively bar scene in season. The setting is stunning, the curved bay and whitewashed houses standing out in stark contrast to the orange-stained cliffs above, while the claw-like Çukurbağ peninsula juts out west, hosting more hotels, villas and apartments. From Antiphellos remain a small Hellenistic theatre and a tottering Lycian tomb on Uzun Çarşı, but these are incidental to the joy of browsing the shops and sampling the cafés.

Kaş harbour

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Beaches are little better than at Kalkan, so boat excursions are popular, including to the Greek island of Kastellórizo (Meis in Turkish) immediately opposite. The top domestic destination is the Kekova • [map] region, where you can peer at submerged ruins on the north shore of Kekova islet, explore the picturesque tombs of ancient Teimiussa and Simena, or climb the Crusader castle at the gulf-side village of Kale. Trips also leave from Üçağız, also on the Kekova shore, and Çayağzı near Demre.

Demre (Myra)

Demre ª [map], 35km (21 miles) east of Kaş, is a busy farming town adjacent to ancient Myra, where tourism seems to be an afterthought, with just two sights to detain you. The first is the Church of St Nicholas (Noël Baba Kilesisi in Turkish; daily summer 9am–7pm, winter 8.30am–5.30pm; charge), originally built during St Nicholas’s tenure as local bishop (for more information, click here). The saint’s body was stolen by Italian traders in 1087 and is now in the Basilica of San Nicola in Bari, Italy. The church was extensively rebuilt by by Tsar Nicholas I of Russia in 1862 and modified more recently by Turkish archaeologists, but fresco traces remain, and the place is a major centre of pilgrimage for Russians.

About 1km (1⁄2 mile) inland are the remains of ancient Myra (daily 8.30am–7.30pm in summer, closes 5pm in winter; charge), with a fine theatre where many relief masks adorn toppled bits of the stage, and numerous magnificent house tombs, some still preserving faint traces of their original paint. Nearby, Hadrian built a huge granary next to Myra’s harbour at Andriake, just inland from the modern port (and beach) of Çayağzı. There is a superior beach nearby at Sülüklü.

Finike and Arykanda

From Demre, the road rounds the coast to Finike, 30km (18 miles) east – another agricultural supply town whose tourism is largely confined to its excellent marina, a popular start- or end-point to coastal gulet cruises. Of the two nearby ancient sites, Limyra and Arykanda q [map], the latter – 34km (21 miles) miles north along Highway 635 – is far more worthwhile. Its ruins (24hr; charge if warden present) enjoy a setting justifiably compared to Delphi in Greece, overlooking a deep valley between two high mountain ranges. Close to the car park, a basilica has fine mosaic floors, while nearby an impressive baths complex stands 10 metres (33ft) high at the façade. Further uphill are monumental tombs, an appealing theatre and attractive stadium sheltering under pines.

Olympos and Çıralı

From Finike, Highway 400 continues around the southeasternmost shoreline of Lycia 30km (19 miles) to the first turning down to the hamlet of Olympos, the closest spot the Turkish coast has to a backpacker hangout. Totally unlike any other local resort, this hidden valley is lined with a half-dozen so-called ‘treehouse’ lodges, beloved in particular of antipodeans in the weeks before and after Anzac Day at Gallipoli.

Olympos Beach

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Olympos Teleferik

The mountains above Çıralı are part of the Beydağları National Park, their entire length threaded by the Lycian Way. An easier way to see the mountains is via the 2006-inaugurated Olympos Teleferik (www.tahtali.com; daily half-hourly 9am–7pm in summer, 10am–5pm in winter; charge), the longest cable-car ride in Europe at 4,350m (13,500ft), and the second-longest in the world. From the base station near the Phaselis turn-off, 736m (2,415ft) above sea level, it takes nearly 10 minutes to power its way up to the summit of Mt Tahtalı (the ancient Mt Olympos) at 2,365m (7,759ft), its distinctive cone-shape so pointed that the top had to be flattened to make space for the cable station, viewing deck and restaurant. The 360º views from the top are superlative.

At the seaward end of the valley, ancient Olympos w [map] (daily summer 9am–7pm, winter 9am–5pm; charge) was an important city in the Lycian Federation, but was taken over by pirates during the 1st century BC, freed by Pompey in 67 BC and later joined to the Roman Empire. The peaceful ruins straddling a stream are only partially excavated and well overgrown, but the diligent will find an aqueduct, villa, arcaded warehouse, a monumental doorframe and – emerging at the bay – inscribed tombs with Byzantine-Genoese fortifications just above.

The next side-road from Highway 400 descends to the more ‘adult’ resort of Çıralı, though still with a slightly ‘alternative’ ethos and a superb long beach protected from overdevelopment by the forestry service – and its role as yet another turtle-nesting site. Many pansiyons and even a few discreet hotels sit a respectful distance inland, amongst citrus orchards. Still further inland and uphill at Ulupınar are a cluster of trout farms with attached restaurants; choose carefully, as some have become used to easy pickings from coach-tour groups.

From Çıralı, an uphill walk (or tractor-bus-ride) leads to the Chimaera (24hr; charge), an extraordinary natural phenomenon, best seen at dusk, in which flames, fed by methane-rich gases, issue from rock fissures. It is named after a mythical fire-breathing monster reputed to have had the head of a lion, the torso of a goat and the tail of a serpent, which was slain by local hero Bellerophon riding the winged horse Pegasus as a task set to attone for his supposed rape of the King of Xanthos’ daughter. The place understandably became a shrine to Hephaestos (Vulcan), the god of fire, and also for Mithraism, an important Roman mystery religion of Indo-European origins, The flames also served as a natural lighthouse for ancient mariners.

Phaselis

About 20km (12 miles) north of the Çıralı turning, the highway reaches the access road down to Phaselis e [map] (daily summer 8.30am–7pm in summer, 9am–5.30pm in winter; charge). With its perfect mix of ancient ruins, sheltered beaches and shady pine forests, this makes a great day-trip, and gulets arrive by the score in the morning disgorging trippers. A 7th-century BC colony of Rhodes, the city prospered despite (or because of) a reputation for sycophancy and obsequiousness when met with superior force, exporting timber, rose oil and perfumes, and providing a base for pirates. There are three harbours: the fortified, exposed north harbour; the central harbour for military and small trading vessels; and the south harbour where larger vessels docked, today with the longest, sandiest beach. The main paved avenue, flanked by houses, baths a small theatre and one of the longest known Roman aqueducts, links the middle and south ports.

Phaselis beach

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Pamphylia

Antalya marks the transition between the wild beauty of the Lycian coast and the tamer plains of ancient Pamphylia. The landscape was not always like this – only in Byzantine times did earthquakes and silt push the coastline away from the mountains and silt up the harbours of the ancient cities. Results include a wide coastal plain with plentiful land for intensive agriculture, development and, from the tourist’s point of view, lovely long sandy beaches that are ideal for paddling but scenically dull.

Antalya

Described by Turkish poet Mehmet Emin Yurdakul as ‘a charming girl watching her beautiful visage in the clear mirror of the Mediterranean’, Antalya r [map] has elicited paeans of praise from visitors across the centuries – including Ibn Battuta and Freya Stark. According to legend, 2nd-century BC King Attalos II of Pergamon chose the spot for the city because it was ‘heaven on earth’. These days, Antalya is a huge city, the eighth largest in Turkey with a population of just over one million and getting bigger all the time. But with its broad bay, backed by the seasonally snow-capped Toros Mountains, and the lozenge-shaped central harbour surrounded by the walled old town, Kaleiçi, it is still incredibly beautiful. It also has a good collection of boutique hotels, excellent restaurants, sophisticated clubs and bars, and excellent shopping.

The town’s closest beach lies to the west in modern Konyaaltı district, backed by hotels, restaurants, parks and entertainment venues. This is also the home of the Antalya Müzesi A [map] (2km (1 mile) west of the town centre; Tue–Sun summer 9am–6.30pm, winter 8.30am–4.30pm; charge), a truly world-class museum, with many of the statues and mosaics from Perge, Aspendos and Xanthos, as well as early prehistoric items found locally, a superb selection of decorative sarcophagi, and ethnographic collections covering everything from carpets to traditional dress and carriages. Look out for the silver reliquary that once held the bones of St Nicholas.

The Fluted Minaret (Yivli Minare)

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Fine facilities

‘There are eight bath-houses in the city, most within the walls, and a bazaar on the outskirts. Here there are twenty Muslim neighbourhoods and four Greek neighbourhoods, but the non-Muslims know no Greek. The harbour has space for two hundred ships, but since wind and gales are frequent in the harbour, the ships moor to high rocks on the shore.

The renowned Turkish traveller Evliya Celebi, who visited Antalya in 1671–2.

The city’s other sites are all within the walls of Kaleiçi, entered through Hadrian’s Gate B [map], a triumphal arch built when the emperor visited in AD130. Nearby are the Saat Kulesi C [map] (clocktower) built in 1244 (although the clock was added much later), 16th-century Mehmet Paşa Camii D [map] and the distinctive Yivli Minare E [map] (Fluted Minaret), with its decorative turquoise and blue tiles, whose adjoining mosque is now an art gallery. Write a wish and put the paper in the ancient olive tree next to the minaret and it will come true. Further along, the Kesik Minare F [map] (Broken Minaret) is an all-purpose religious site that has, in its time, been a Roman temple, a Byzantine church and an Ottoman mosque. On the headland overlooking the harbour, the squat round Hıdırlık Kulesi G [map] may have begun life as a lighthouse in the 2nd century AD. The only museum in Kaleiçi is the Mediterranean Civilisations and Research Institute (Suna-İnan Kıraç Akdeniz Araştırma Enstitütü H [map]; Kocatepe Sok 25; Thur–Tue summer 9am–noon & 1–6pm, winter 9am–noon, 1–6pm; charge), a small, private museum occupying two restored Ottoman mansions and the Orthdox church of Agios Georgios. The church contains Çanakkale ceramics, the houses rich archives and rooms restored as tableaux. Antalya’s oldest hamam (bath-house) is just opposite. All around are a maze of small steep streets and alleys filled with old Ottoman houses, many restored as accommodation, restaurants and shops that make this an ideal place to stroll, stopping for an occasional glass of black tea and some hard bargaining. Boat trips leave from the old harbour.

Hadrian’s Gate

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Termessos and Karain Mağarası

From the car park, it takes a good 25 minutes to ascend to the romantically unexcavated ruins of Termessos t [map] (37km/22 miles northwest of Antalya; daily summer 9am– 7pm, winter 9am– 5pm; charge) which teeter precariously under the rugged crags of Güllük Dağı. Even Alexander the Great gave up on the climb as its notoriously warlike and freedom-loving citizens hurled boulders over the ramparts at his troops. For those who make the trek, the setting is incomparable, with the theatre sandwiched between a cliff and a deep gorge. Termessos also has a large gymnasium, odeon, Zeus temple, cisterns and a necropolis. The surrounding Güllük Dağı National Park is surpassingly beautiful, its conifer forests home to wild goats and fallow deer.

Termessos amphitheatre

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

The Toros (Taurus) Mountains are riddled with caves, many bearing evidence of human and proto-human habitation going back millennia, as well as fine stalactite and stalagmite formations. Some are open to the public, others can be visited by expert cavers. The first people started living in Karain Mağarası y [map] (Karain Cave; 27km/17 miles northwest of Antalya, off Highway 650 to Burdur; 6km/4 miles from the main road; daily 8.30am–5pm; charge) about 30,000 years ago, and habitation continued for another 20,000 years, producing an invaluable stream of prehistoric evidence. It is easy to visit, with stairs, lights and a small site museum.

Perge and Belek

As you leave Antalya and head east, the main road is lined by outlet malls, discount stores and huge emporia selling everything from gold and diamonds to carpets.

The Kurşunlu Şelale u [map] (Kurşunlu Falls; 23km/14 miles east of Antalya, 7km/4miles off main road; daily 8.30am– 5.30pm; charge) is a popular daytrip for families from Antalya, with a picnic area and walks surrounding high, stepped waterfalls.

Kurşunlu Şelale

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

A few kilometres further on, Perge i [map] (Perga in Greek; daily 9am–7pm in summer, until 5.30pm in winter; charge and parking fees) is one of the most extensive and best preserved of Turkey’s ancient cities. Founded by some time after 1100BC, it was used by Alexander the Great during his Pamphylian campaign, eventually passing to Pergamon and finally expiring late in the Byzantine era when its harbour silted up. The impressive monuments begin on the drive towards the main site with the 14,000-seat theatre (closed for works) and a superbly preserved 12,000-seat stadium (both 2nd century AD). The entrance was through the giant red 3rd-century BC Hellenistic gates from where visitors could turn left towards a series of elegant and highly sophisticated baths, right towards the 4th-century AD forum or continue straight along the colonnaded main street, its marble paving stones still clearly showing the ruts of carts and carriages, many of the shops to either side still with mosaic floors. At the far end, on the acropolis, are fragmentary remains of the earliest city. Perge is one of the start-points for the St Paul Trail (for more information, click here).

Until the early 1980s, the long stretch of flat sand beach between Perge and Aspendos was virgin territory. Now there is a whole town, Belek o [map], complete with shopping malls, a long line of luxury hotels, a great many apartment blocks and – the focus for all this frenetic building – 16 world-class championship golf courses, with more planned. Many people who stay here never get further than the golf links, but most of the hotels lay on a variety of other activities. Belek is within easy reach of Antalya and the local sights, the beaches are superb (a view shared by local loggerhead turtles, for more information, click here), and it’s affordable.

Aspendos and Köprülü Kanyon

Aspendos p [map] (31km/19 miles east of Perge, plus 5km/3 miles more from main road; daily 9am–7pm in summer, 8.30am–5pm in winter; charge) was probably founded at about the same time as Perge. Although now several kilometres inland, it was a port, specialising in luxuries and staples such as salt, oil, wine and horses, and once it became the property of Pergamon, its wealth and status were assured. But while there are various remains here, few visitors notice them, choosing to concentrate solely on the fabulous 15,000-seat theatre, built by the architect Zeno during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD161–80), and probably the finest surviving Roman theatre in the world. It seats up to 15,000, with 40 rows of marble seats divided by 10 staircases in the lower section and 21 above. A richly decorated stage wall once held marble statues, most of which are now in Antalya Museum. It is still used for an annual June festival of ballet and opera (for more information, click here) as well as other events. Elsewhere, look out for the elegant 880m (2,888ft) stretch of aqueduct (1st century AD) and the beautiful 13th-century Selçuk stone bridge across the Köprüçay.

The theatre at Aspendos

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Rafting the Köprülü Kanyon

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Just after Aspendos, a road turns off inland climbing into the foothills along the Köprü river valley. After about 43km (28 miles) a cluster of little restaurants marks the beginning of the Köprülü Kanyon Q [map], a stunning chasm that offers some of the country’s most famous (and most crowded) whitewater rafting, great wild trout for fishermen and gourmets and lovely walks in the fresh mountain air. A single-arched Roman stone bridge crosses the gorge and a gravel road uses it, climbing ever higher to the village of Altınkaya (Zerk) where the ruins of ancient Selge, once a city of 20,000 people, are threaded amongst back-garden cabbages and fruit trees in a spectacular setting.

Side and Alarahan

Pronounced ‘See-day’ and meaning pomegranate (a symbol of fertility) in a lost Anatolian language, Side W [map], 38km (24 miles) southeast of Aspendos, has been a holiday resort since Anthony and Cleopatra met up here, supposedly to negotiate a timber concession. Then it combined hedonistic pursuits with piracy and slaving; these days, it concentrates on the former. The ancient monuments are threaded through the modern resort, which is delightful out of season and, while tamer than it once was, can still be a heaving mass of alcohol-fuelled bodies in summer. Resort hotels fan out along the beaches to either side of the core old village on its promontory. At the entrance to the town centre are the freestanding, 20,000-seat theatre and the Archaeological Museum (Tue– Sun summer 9am–noon, 1.30–7.30pm, winter closes 5.30pm; charge) housed in the former Roman baths. Beside the former harbour, perfectly positioned to catch the sunset, are the Temples of Athena and Apollo.

Dining out in Side

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Manavgat is Side’s much larger neighbour, with little to recommend it to tourists other than boat trips to the local waterfalls. At Alarahan E [map] (35km/22 miles east of Side, 9km/6 miles off the main road; daily 9am–11pm) is one of the finest of some 200 Seljuk kervansaray, built in about 1231 by Seljuk Sultan Alâeddin Keykubad I for those travelling the Silk Road between Konya and Alanya. Set a day’s journey apart, these institutions offered lodging to travellers and their animals, along with medical assistance and spiritual guidance. Today, the interior is full of souvenir stalls, with one hall set aside for entertaining tour groups with dinner and belly-dancing. An impressive Byzantine-Seljuk fortress, reached by a steep 15-minute walk, garlands the mountain just north of the kervanseray.

Alarahan fortress

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Alanya

Alanya R [map], 39km (24 miles) east of Alarahan, was until the millennium an almost entirely German domain, although the Brits and Russians are now invading in search of cheaper property prices and huge sandy beaches. With its own international airport 40km (25 miles) away at Gazipa, further exponential growth around this resort is assured.

Alanya is not particularly attractive, with ranks of mass market hotels and apartment blocks both in town and stretching out along the beaches. İncekum, 20km (12 miles) west, is the place to come if reasonably priced sun, sand and partying is your thing. However, it does also have some history, with a fortress built by a 1st-century BC pirate chief, Diodotus Tryphon, before he was kicked out of the region by Pompey; Coracesium, as Alanya was then known, soon joined the Roman Empire. In 44BC, Mark Anthony gave the whole region to Cleopatra. The city became Kalonoros under the Byzantines and was then renamed again by Seljuk Sultan Alâeddin Keykubad I in 1221 when he made the town his summer capital.

Near the harbour the 35m (115ft) Kızıl Kule (Red Tower) was built in 1226 by a Syrian architect for Sultan Alâeddin Keykubad I to protect the dockyard. Inside it has five storeys, with arched galleries surrounding a huge water cistern. The tower now houses a small ethnographic museum (Tue–Sun 9am–noon, 1.30–7pm; charge). The main Alanya Museum (Azaklar Sokağı; Tue–Sun 8.30am–noon, 1.30–5.30pm; charge) is small but well-displayed, with a mix of archaeological and ethnographic displays.

Alanya Harbour

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Nearby, Damlataş Mağarası (Weeping Cave; 10am–6pm; charge) has two chambers with great stalactite and stalagmite formations, high humidity and elevated levels of carbon dioxide, natural ionisation and radiation that make it a supposedly great cure for asthma and rheumatism (if you sit in the cave daily 6–10am for 21 days).

Damlataş Mağarası

Frank Noon/Apa Publications

Boat trips round the harbour are the only way to see the Tersane, the last remaining Seljuk dockyard in Turkey, dating from 1227. Positioned right on the water, it consists of a row of five huge open workshops with arched roofs. The trips also offer spectacular views of various sea-caves and the Citadel (daily summer 9am–7.30pm, winter 8.30am– 5pm; charge), built onto a soaring 250m (820ft) seacliff and surrounded by vast defensive walls with 150 bastions and 400 water cisterns. If you want to go up, there are 4km (21⁄2 miles) of hairpin bends to climb, or alternatively a bus service.