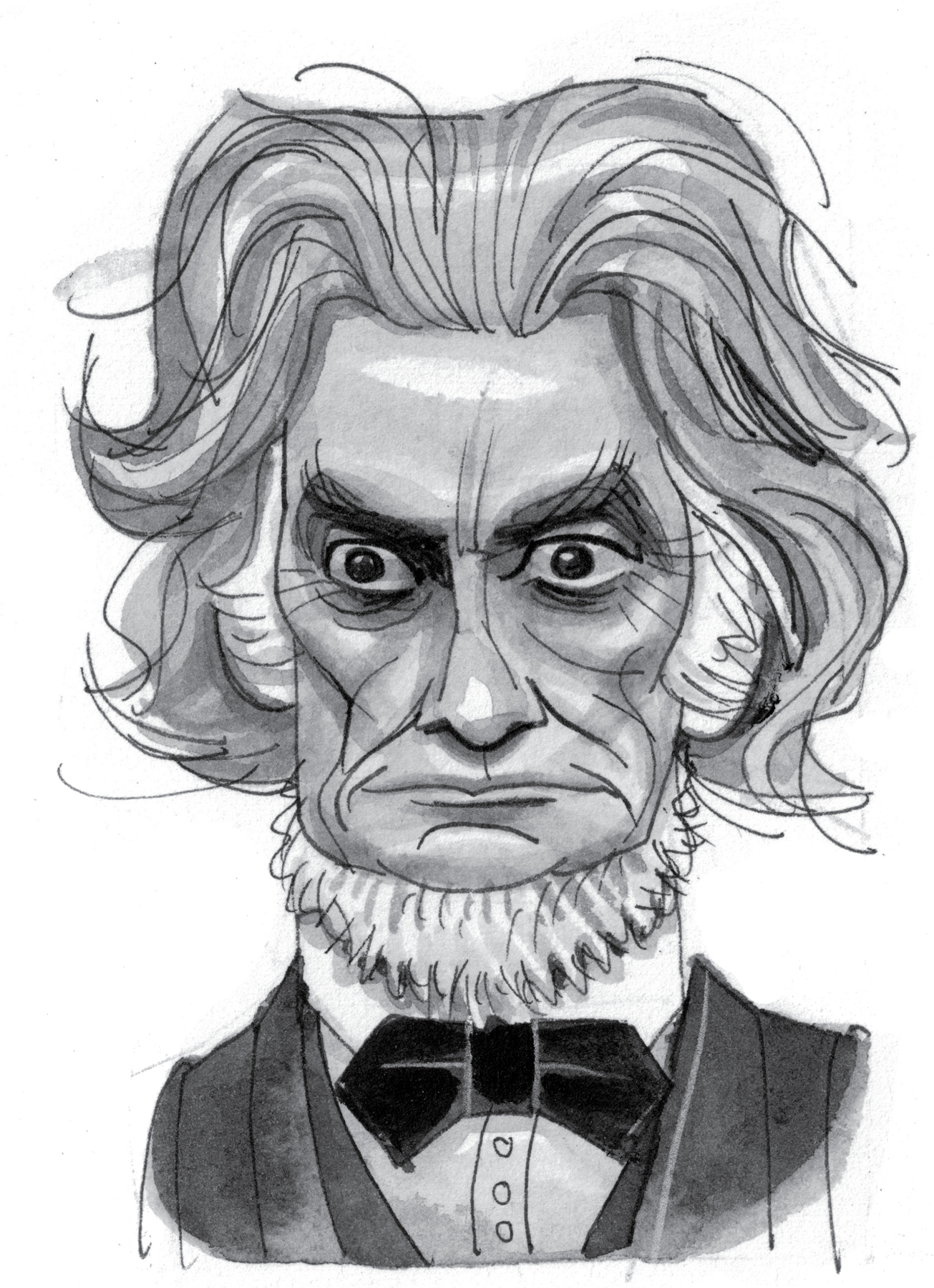

John C. Calhoun

BA, Yale University

John C. Calhoun was a prominent American politician, statesman, and public intellectual during the first half of the nineteenth century. Among other accomplishments, he was:

• Elected congressman and twice elected senator from his home state of South Carolina

• Appointed secretary of war by President James Monroe

• Twice elected vice president, serving under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson

• Appointed secretary of state by President John Tyler

• A brilliant orator who was known as the Cast-Iron Man for his unbendable convictions

Impressive, even for a class of 1804 Phi Beta Kappa Yale graduate. Except for one problem.

The man loved slavery.

Adored it. Wanted to marry it. Thought it was the bee’s knees. Waxed eloquent about it. And in his waxings, unlike the many apologists for slavery who argued that it was a “necessary evil,” Calhoun proclaimed it a “positive good.” Slavery, to this gentleman, reflected the God-given superiority of the white race and conferred benefits on everyone, including the slaves themselves. And isn’t it great when that happens? When, while getting rich oppressing others, you’re not only serving the Almighty but actually doing good for the oppressed? You bet it is.

Still—and how is this even fair?—there are pesky do-gooders in every society. As antislavery sentiments bloomed in the North, Calhoun’s rhetoric turned from moral and religious to calculatedly political, invoking “states’ rights” and the concept of “nullification,” in which a state can—and must!—overrule the federal government when it starts getting too uppity. And, don’t you know, we hear these terms from Republicans—mostly from the South, but not exclusively—to this very day. Isn’t it funny, how little some things change over time?

Although Calhoun, who died in 1850, did not live to witness the logical conclusion of his prodigious speechifying, he more than anyone else could be said to be the guy who started the Civil War. Too much? Okay. Then let it be said that he was one of slavery’s most eloquent, rigid, and self-righteous defenders. Better?

Over the course of Yale’s first two centuries, Calhoun was the only graduate to be elected to a superprestigious position in the US government. Ergo, Yale is, or at least was, proud of its association with him and is, or was, rife with commemorative Calhounabilia, including a statue perched, alongside statues of other notable graduates, on the Gothic gingerbread of Harkness Tower; a residence called Calhoun College; and, within this residence, a stained-glass depiction of the man himself, posing with a kneeling, shackled, and no doubt grateful black man.

Alas (for those sympathetic to slavery, states’ rights, and Calhoun—we know you’re out there), it eventually dawned on a significant number of students, faculty, and Yale administrators that glorifying not just “a racist,” but a proud-talking, Bible-thumping, opposite-of-apologetic racist, might strike some as being slightly offensive. (By “some” we mean blacks, whites, Asians, Latinos, men, women, civilized persons, and humans in general.) Such a policy might arguably not be in the school’s best interest. So in 1992 Yale slapped up a poster in Calhoun College acknowledging the controversial nature of the dorm’s eponym.

But how to address the problematic nature of the stained-glass masterpiece depicting Calhoun’s dominion over and ownership of a slave? Easy: Yale brought in an artisan to remove the slave from the artwork. Now, if the Communist Party of the Soviet Union had done something like that to a painting of Stalin—say, removed from a group portrait the faces of men he was discovered to have brutally murdered, but kept the rest—we would have tsked and tutted and shaken our heads in appalled moral superiority. Yale, though, went about its business, perhaps resisting the urge to replace the slave with a sign reading YOUR AD HERE.*

Of course this did not settle the issue.

There are those who want to cleanse Yale of all overt associations with John C. Calhoun, to toss him down the memory hole, as it were. But whitewashing the past is not the way it’s done—or, at least, should be done—by an institution dedicated to, among other things, researching, teaching, and attempting to understand history.

Here’s our suggestion: Rename the dorms, then scoop up the artifacts associated with all the honored Yalie miscreants (there are plenty of them; we’ve pointed out some of them right here in this book), and deposit them in their own little museum. Create an Ivy Hall of Shame, as it were. Don’t worry about funding it; some rich graduates destined to be enshrined therein will surely pay for it as long as their names are spelled correctly and they have approval of their portraits and/or busts. Let it be a place of study, contemplation, and learning, of service to anyone looking to counteract the delusional belief that the mere act of graduating from such an establishment necessarily places one on the right side of history.