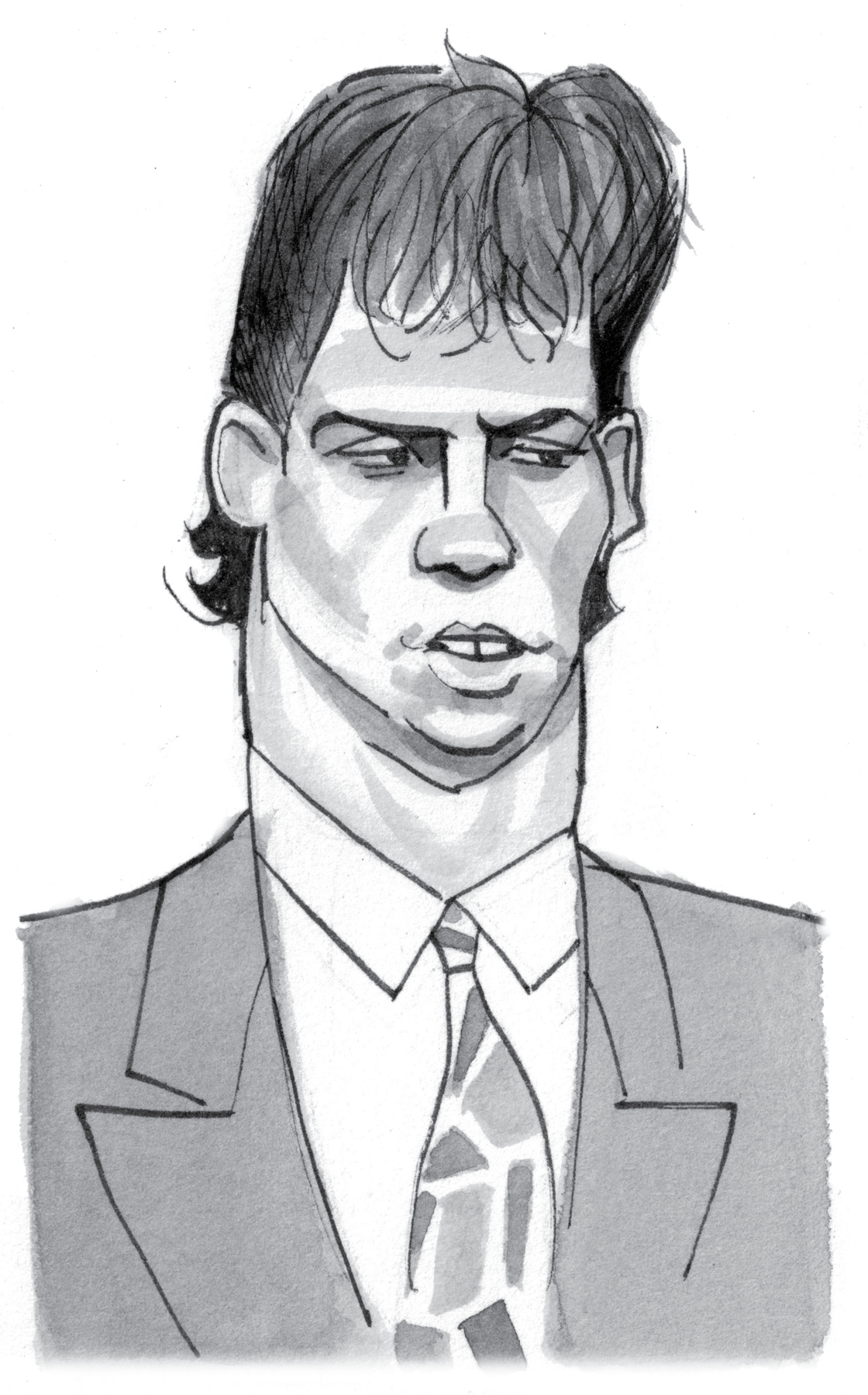

Lyle Menendez

Princeton University Dropout

You might argue that it’s wrong to include in this book someone who was suspended from Princeton during his first semester, never to return. We’d argue right back that in this case the magnitude of the monstrousness compensates for the minimal Ivy exposure. If we were feeling really argumentative, we’d assert that, just maybe, even a fraction of a semester at Princeton can irreparably warp an impressionable young mind. In any event, Lyle Menendez, Princeton dropout, made our cut.

Lyle and his younger brother, Erik, were the sons of Jose and Kitty Menendez. Jose, a hard-driving first-generation American, had emigrated from Cuba as a child, earned an accounting degree from Queens College,* worked his ass off, zigzagged upward through the ranks of various industries, and finally earned a slot not far from the pinnacle of American capitalism as a highly compensated show-biz executive in sunny California.

But Jose’s success did not extend to his and Kitty’s child-rearing. Possibly in rebellion against Jose’s high expectations, possibly because they knew their parents would bail them out of whatever trouble they got into, possibly because they were twisted, greedy little pricks, Lyle and Erik launched a plan to break into their neighbors’ houses in Calabasas and steal expensive stuff. They managed to pull off two burglaries, netting more than $100,000 in cash and jewelry, before a friend turned them in.

Jose’s response was to make them return the loot while reprimanding them for getting caught.* And, in order to protect Lyle’s chances of getting into Princeton—one of Jose’s big American dreams—he convinced the authorities that Erik, just eighteen, had masterminded the crimes. This neatly got Lyle off the hook and kept Erik from being saddled with an adult criminal record. Dad then quickly moved the family to a biggish house in Beverly Hills, just far enough away from Calabasas that none of their new neighbors were likely to have heard of Lyle’s and Erik’s burgle-tastic past.

Lyle did indeed get into Princeton. We’ll report only two items about his tenure there. First, he drove an Alfa Romeo, courtesy of his parents, which he told a classmate was, and we quote, a “piece of shit” compared to the Porsche he deserved. Second, he was caught cheating on an exam and was slapped with a one-year suspension. So Jose wouldn’t have to explain to anyone why his Ivy League son was back in Beverly Hills so soon, he insisted that Lyle stay in (if not at) Princeton through the academic year.

When Lyle did return home, he and Erik hatched a plan, based largely on the plot of the film Billionaire Boys Club (and the real-life Ponzi-cum-murder scheme it was based on),* to murder their parents and claim their inheritances ahead of schedule. Their plan was simple, involving nothing but easily obtainable guns and ammo. On August 20, 1989, Jose and Kitty stayed home while Lyle and Erik pretended to be out with friends. At around 10 p.m. the boys slipped into the den, where their father was watching television with their mother dozing by his side. The first shot, a point-blank blast to the back of dad’s head, woke mom. She flew off the couch but before she could escape they shot her in the leg and sent her sprawling to the floor. As she scrambled, they fired several more times, shredding her body and pulverizing her face. Blood and guts everywhere. Then, in a stylish cinematic flourish, they kneecap-shot each parent in order to plant the thought “Mob hit!”* in the minds of crime-scene investigators. The lads then hopped into a car, dumped the guns, and tried to establish an alibi by seeing a movie and afterward hanging with friends. Then they returned home, “discovered” their slaughtered parents, dialed 911, and played the part of a couple of nice rich kids who were deeply upset, practically unhinged, by the grisly scene.

Soon enough the boys dried their tears and got busy consoling themselves with their $14 million windfall. Lyle bought himself that Porsche 911, plus a Rolex, plus a restaurant he favored back in Princeton; Erik hired a full-time tennis coach to help him compete in professional tournaments overseas. Together, and without even bothering to offload the family murder-manse, they bought a pair of penthouse apartments in Marina del Rey, trotted the globe, explored luxury dining, and pursued countless other richy-rich activities.

Six months after the double parricide, the brothers’ spending bender was cut short by their arrests. The first trials ended deadlocked after their mutual lawyer thoroughly flummoxed the juries with megatonnage of tabloid kibble featuring tales of the sexual abuse poor Lyle and Erik had suffered at the hands of their allegedly psychopathic parents. The second pair of trials reached more satisfying conclusions: life in prison without parole for both murderers.

So here’s what you’ll do the next time an obnoxious friend or relative proudly informs you that he or she, or his or her kid, got into Princeton. You will pause thoughtfully for a moment, sigh sadly, and say, “Didn’t one of those little twerps who killed their parents get in there?”