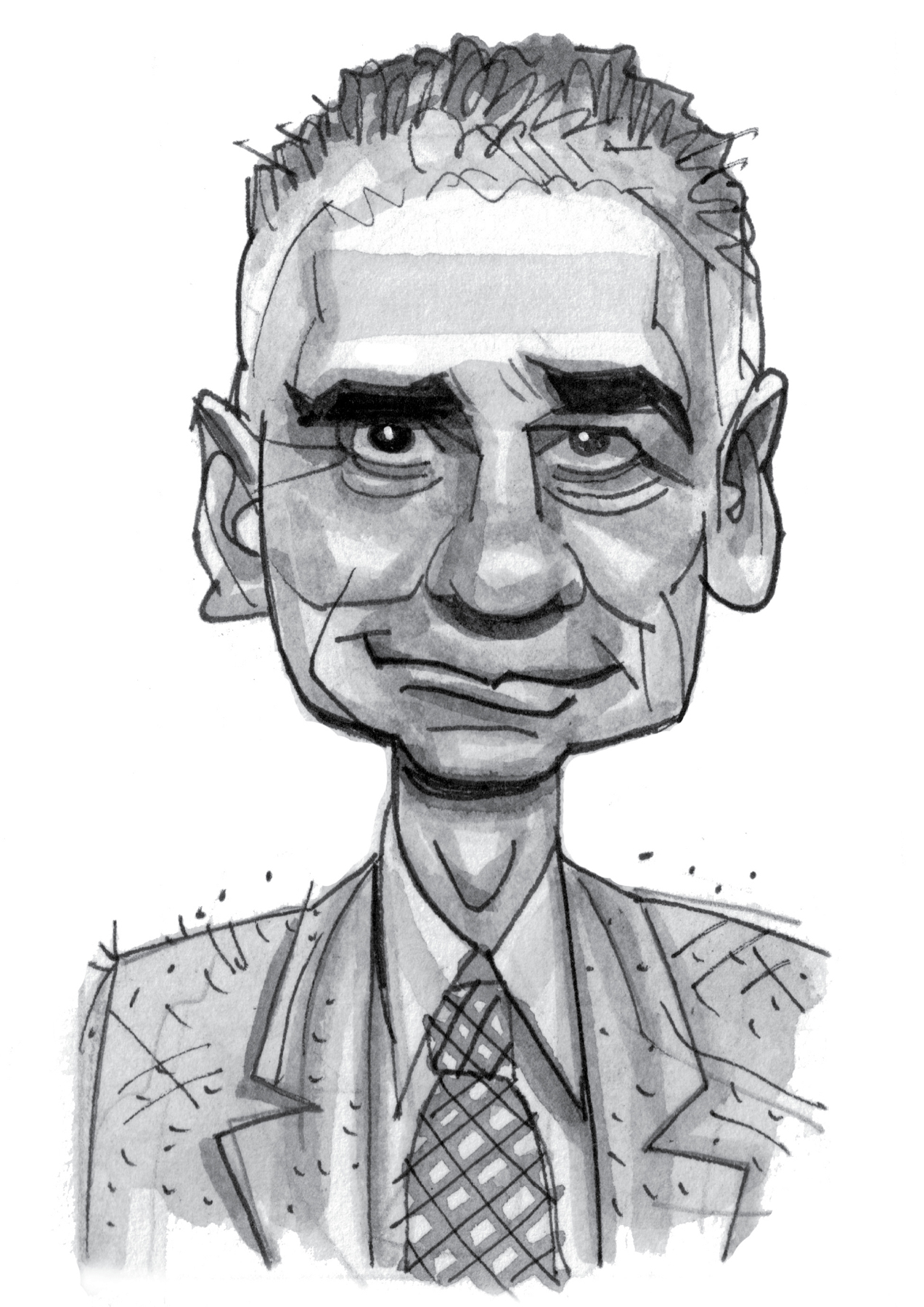

Ralph Nader

BA, Princeton University  LLB, Harvard University

LLB, Harvard University

Hunched inside a rumpled suit, Ralph Nader may not look like a man driven by ambition. But do not be fooled. He holds himself in the same imperious self-regard as any other Ivy League monster. Not that he hasn’t done his bit to help humanity, with the nonprofits he’s spawned, the corporate nimrods he’s skewered, the seat belts he’s caused to be buckled, the shoddily made cars he’s caused to be unshoddily unmade.

And yet, when we think of him, we can’t help recollecting that terrible election of 2000, when the forces of purest E-vil (the Republican Party, the Supreme Court, etc.) conspired to hand George W. Bush a huge prize he had not won, after which… well, some other stuff happened.

That year, Nader ran as the Green Party presidential candidate, against both Republican Bush and Democrat Al Gore. While Nader had zero chance of winning, polling indicated that he would likely do much better than he’d done in the 1996 election, when he received all of 0.71 percent of the votes. As the race tightened, knowledgeable observers began to speak of Nader as a potential spoiler. In the closing weeks of the campaign, many wondered whether he would (from the point of view of the center-left and left) do the right thing and, if there was a chance he might suck just enough votes from Gore in certain states to tip the race to Bush, withdraw.

It all came down to Florida, where Nader campaigned heavily, accusing the major parties of being identical, calling Gore and Bush Tweedledee and Tweedledum, and making it clear that those who were nervous that his candidacy might lead to a Bush presidency could go fuck themselves. (That wasn’t his language, but somehow one knew what he meant.)

In the end, more than 5.8 million votes were cast in Florida. According to the official-if-disputed count, Bush beat Gore by a mere 537 votes. Close! Except that nearly 100,000 people voted for Nader. Sure, they wouldn’t all have voted for Gore had Nader dropped out. Some wouldn’t have voted at all. And, yes, some would have voted for Bush.

It’s even likely that some registered Democrats would have switched from Nader to Bush. (Gore was a terrible campaigner: “Lockbox! Lockbox! Lockbox!”) According to some widely respected and unbiased political observers, it’s not out of the question that Bush would have won by a wider margin had Nader dropped out. Granted, such a voter’s thought process would have to have been something like: “Hmm. I was going to vote for the Green Party’s antiestablishment, anti–big business, left-of-the-Democrats candidate. But if he’s not running, I guess I’ll vote for a bumbling rich kid who couldn’t make a living in oil in Texas, and whose millionaire Republican father has been head of the CIA, vice president, and president.” Then again, some exit polls suggested that there were people who actually did think this way, so go understand people.

Or don’t bother. Instead, ask yourself, “Did Nader’s 100,000 votes make it possible, or at least easier, for the GOP vote-miscounting squad and the Supreme Court to foist Bush on the nation?” Even if the answer is “Maybe; we just don’t know,” there are some things we definitely do know. We know that Nader was well aware that the race was exceptionally tight, that his candidacy might throw it to Bush, and that he insisted it didn’t matter because Bush and Gore were essentially the same person, the Democrats and the GOP the same party. But he was wrong about that. It did (and does) matter. Nader’s the-parties-are-identical position was no different from today’s media’s self-serving/lazy/cowardly explanation for gridlock in Washington, the “both sides do it” false equivalence that passes as insider savvy or “balance” while being demonstrably untrue. Nader had a chance to wield a political superpower, to bow out, endorse (and maybe campaign for) Gore, and with that one act, help—or at least try to—defeat the titanically mediocre Bush. Instead, from the lofty height of his idealism, ego, and political purity, he colluded in ushering in eight years of bumbling monstrosity.

Like any smug ideologue who’s been drinking his own Kool-Aid for too long, Nader cannot admit when he’s wrong. He was and is unapologetic about his role in helping elect George W. Bush. He’s happy to list all the reasons why his vanity run for president couldn’t possibly have had anything to do with the Florida debacle. And it’s a good bet he’s still insisting that there’s no difference between Democrats and Republicans, and therefore that the events of 9/11 and the ensuing clusterfuck in the Middle East would have gone no differently under a Gore presidency. And if he does think that, he must be the only person in the country who does.

So, sure, Ralph Nader did some good work. Tragically, he seems incapable of understanding Voltaire’s famous dictum Le mieux est l’ennemi du bien (The best is the enemy of the good). Which, in the context of Ralph Nader, means that certain egomaniacs turn a blind eye when their precious principles, so noble in the abstract, wreak disaster when they intersect with the real world.