CHAPTER TWO

The Somme:

March 1916 – December 1916

1 Accidental Deaths in the Line – May, 1916

2 Private Percy Crabtree – June

3. 1 July a) 2/Lt. Bart Endean – buried alive

b) Pte. Fred Sayer – in the dug-out

c) Pte. Harry Fielding – prisoner of war

d) Pte. Fred Sayer – journey to the rear

4. Casualties and Awards – I July

5. Re-organisation of the stretcher-bearers – July

6. Thoughts on Trench Names – by Percy Crabtree

7. Bitten on the Bottom – by Fred Sayer

8. Hot Tea – December – by Fred Sayer

9. Following the 1916 Trail of the Pals

1. Accidental Deaths in the Line

Pte. Fred Sayer:

‘On 27 May an incident of immense distress concerned one of our original Pals. On a bright summer morning with a certain amount of peace about in the front line, this quiet, steady soldier was cleaning his rifle. It was a drill and he must have done it a thousand times or more. As he finished, he snapped the bolt in place and pulled the trigger. Being in the front line he did not point the rifle skywards, as was usual, for safety’s sake.’

He did not know how it happened but a bullet went through his two pals, killing them both instantly. The anguish of this poor soul can be imagined to some degree, but I cannot conceive anyone realising the suffering he experienced. He was inconsolable. He volunteered for all the dangerous jobs and we knew he was looking for something “with his name on it”. He was killed on 1 July, in company with many of his pals, which was what he wanted.’

Mystery surrounds this incident. Pte. Sayer’s story was corroborated to the author, quite independently, by a veteran present at the time. He described how he, and others, were amazed that the bullet entered the body of the first man at one angle and came out at another – presumably deflected by bone or muscle. The bullet hit the second man, who was seated at the time, in the chest.

The veteran added that although the incident was common knowledge throughout the battalion, no action was taken. Indeed, the words ‘hushed up’ were used. The reason for this is a matter of conjecture but possibly senior officers were anxious to continue with the intense preparations for the forthcoming attack.

The Battalion War Diary offers no clue. The entries for the relevant period simply state:

20 May – Battalion to front line and occupied K29c 1535 to K23d 2535 (map references).

25 May – For first five days no casualties. All available men were working on improvement of front line trench and wiring par ties out every night.

27 May – Two killed, eight wounded.

29 May – Seven wounded. Total casualties in this tour of the trenches – 2 killed, 23 wounded.

30 May – Battalion relieved by 14 York and Lancaster Regiment – to Brigade reserve, Courcelles.

The following letter was written by ‘W’ Company Commander, Capt.

R. B. Tough, to Miss M. Jackson of Clayton-le-Moors:-

‘It is with deepest regret that I have to inform you that your brother, Pte. T. Jackson, was killed in action yesterday, May 27th. He was a splendid soldier and a very bright and cheerful comrade and I can assure you that his death has cast a gloom over the whole company, with whom he was very popular. He was shot through the chest and died practically instantaneously and suffered no pain. I would like, on behalf of the officers and men of his company to express to you our deepest sympathy. – Capt. R. B. Tough.’

Pte T Jackson. (Mr Eric Shaw)

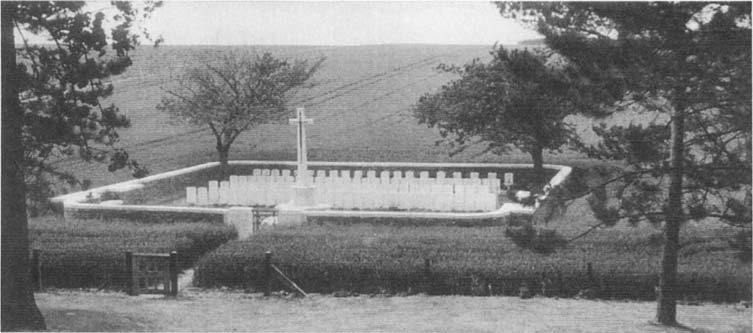

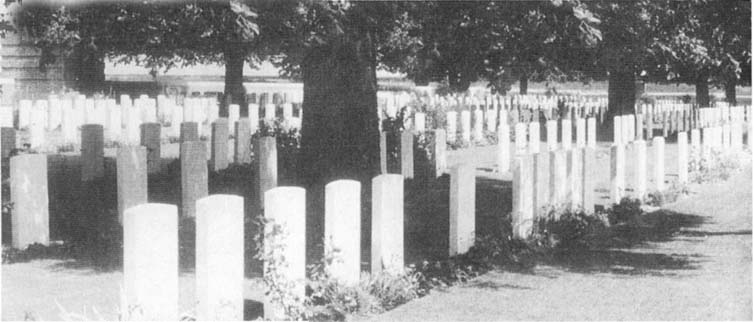

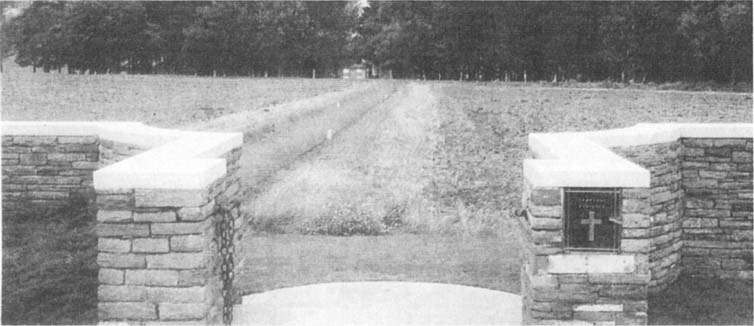

Sucrerie Military Cemetery, Colincamps. (The Pals Collection)

An identical letter was received by the widow of Pte. Robert Pickering of Darwen. Something about the tone of this letter led Miss Jackson to believe this was not the truth. Her enquiries brought no result, and her suspicions were only confirmed when a comrade came home on leave. The name of the soldier responsible was never revealed.

Pte. Thomas Jackson 15935 of Clayton-le-Moors and Pte. Robert Pickering 15942 of Darwen, are buried in Sucrerie Military Cemetery, Colicamps, Grave numbers 1H 53 and 54 respectively.

2. Pte Percy Crabtree – June

On 24 June 1916, a week before the attack on Serre, the Battalion received at Louvencourt a final draft of fifty-eight other ranks and one officer from 12 (Reserve) Battalion at Prees Heath, Shropshire. Amongst them was 24799 Pte. Percy Crabtree, age 28.

Pte. Crabtree enlisted in Nelson in March 1916. He spent ten weeks in training before coming to France. After a short stay at Etaples, he and the rest of the draft arrived at Louvencourt. They had missed the Battalion rehearsals for the attack held at Gezaincourt in mid-June so there was time only for the briefest of preparation and training before 1 July.

Percy, in later years, never spoke of his experiences on that day. We do know that he, in common with the rest of the draft, went into the trenches for the first time ever on 30 June. We also know that two friends, 24787 Pte. Thomas Taylor, age 29, and 24797 Pte. James Allan Watson, age 28, were killed in action. Another friend, 24798 Pte. W. Mallinson, was wounded.

Pte. Taylor is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, whilst Pte. Watson is buried in Euston Road Cemetery in grave no. I G 22.

Percy Crabtree was born in Padiham, near Burnley, in 1888. He returned to teaching after the war. After several local posts he became headmaster of Lomeshaye School, Nelson. In 1944 he was appointed headmaster of Bradley School, Nelson. He retired in 1948. He had a strong religious faith, working all his life for the Methodist church. He was a life-long teetotaller. He was an enthusiastic local historian, photographer and artist in water-colour. He was married with one daughter. He died at his home in Nelson on 8 November 1958.

(Mrs B Brown)

4. 1st July, 1916

The story of 1 July need not be told in any detail. The following brief outline is sufficient. Further information can be obtained from Pals, The 11th (Service) Battalion (Accrington) East Lancashire Regiment, published by Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

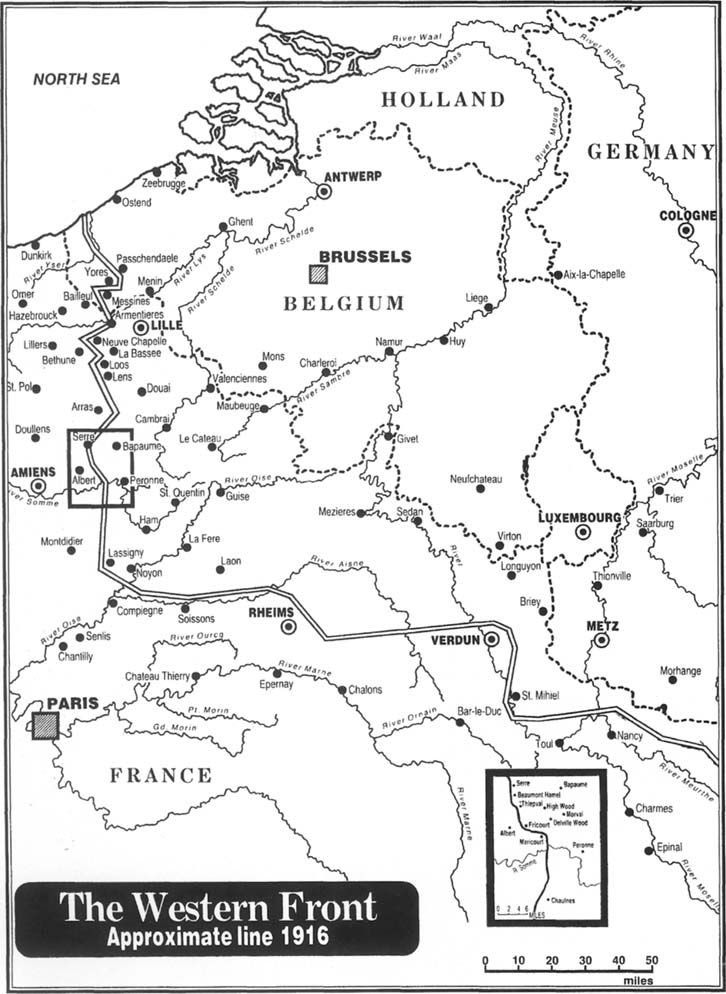

By the end of June some fifteen divisions of General Sir H. Rawlinson’s fourth Army were in readiness for the ‘Big Push’ on 1 July. In Lt. Gen. Sir A. G. Hunter-Weston’s VIII Corps were four divisions of which one was 31st Division. 31st Division was made up of three Brigades – 92, 93 and 94. The Pals in company with the Sheffield City Battalion and the two Barnsley battalions of the York and Lancaster Regiment, made up 94 Brigade.

The principle objective of the British troops in the ‘Push’ was to break through the German defences on an eighteen-mile front from Gommecourt in the north, to Maricourt on the River Somme in the south, and continue eastwards and northwards into the open country beyond. The main task of 31st Division was to capture the fortified village of Serre and secure the northern flank of the hoped-for main breakthrough further south.

The Pals and the City Battalion were to make the initial assault on Serre on 1 July, with the two Barnsley battalions following through. On 24 June there began a bombardment from over 1,400 British guns ‘softening up’, or so it was hoped, the German defences in readiness for the assault.

At 7.30 a.m. in the bright sunshine of 1 July over 700 Pals advanced from their trenches before Serre. Seven days of British artillery fire was supposed to have obliterated the German positions. As the Pals came slowly across the three hundred yards of No Man’s Land the German defenders came up from deep dugouts untouched by the shelling and swept the advancing troops with machine-gun and rifle fire. A few got into the German trenches, a few reached Serre itself but these were never seen or heard of again. Most of the Pals lay in heaps before the barbed wire defences. In less than twenty minutes some 235 Pals died and 350 lay wounded. The attack on Serre was completely repulsed.

A farm house in Serre before 1 July 1916. Note the German soldier near the gateway. (Arrowed) (Mr John Bailey)

One of a series of maps prepared before the attack on Serre. This indicates the expected positions of each company in the second bound. (WO95/2341 PRO)

2/Lt (later Captain) Bart Endean. (Mr Tony Bell)

1 July is so important, however, that it can not be described without the addition of some sort of personal account.

The following tell their own story. Firstly, 2/Lt. Bartholomew (Bart) Endean (before the attack), secondly Pte. Fred Sayer (during the attack) and thirdly, Pte. Harry Fielding’s account, in a letter home, of his capture (one of very few that day). Pte. Sayer ends the selection with a description of his return to the rear after the failure of the attack.

a) 2/Lt. Bart Endean, posted to ‘Z’ Company in April 1916, and later to be the Company Commander, had an experience which possibly saved his life:

‘The night before I July we set off from camp and got into the trenches, maybe at 3 o’clock in the morning. Everyone was carrying extra stuff – extra rations, extra ammunition, flares, flags and all sorts of things. You could hardly move in the trench.’

‘After we had got everybody fixed up I said to Sgt. Ingham “Let’s have a cup of Oxo in that dug-out” The two of us went down, boiled some water on a methylated spirit stove and had a drink of Oxo. When we were coming up again, I thought I would take my equipment off so that Vd be able to move about more easily in the trench. I took it off and hung it on a nail at the bottom of the dug-out steps.

‘We were due to go over the top at half-past seven. At seven o’clock it was, a beautiful morning and the sun was already shining. I made my way to the dug-out, thinking that I’d better get my equipment on. I was just going down the steps when Sgt. Ingham said, “I’ll give you a hand, Sir”. He followed me down. I took my equipment off the nail, turned around, gave it to him, turned around again and I was putting my arms out for him to put the straps over, when a shell dropped right on top of the dugout.

‘When I came to, I said to myself, There goes all my bloody teeth!”. But it wasn’t my teeth. It was a mouthful of dirt I was spitting out. I couldn’t see. I couldn’t get up – every time I tried there was something lying across my back – I think it must have been the timber of the dug-out. I remember saying to myself “I wonder if I’ve got a Blighty one?”. I couldn’t tell whether I was bleeding. I couldn’t feel anything the matter with me. And I didn ‘t know where the sergeant was.

‘After a while I could see a streak of sunlight coming from a corner – one streak of light coming through the darkness as if it were coming from a keyhole. I thought that if I could get nearer to it I might make the hole a bit bigger. But I couldn’t get up. I tried again. I pressed downwards to try to get up and the Sergeant groaned. I knew then he was underneath me. I couldn’t see him. I heard someone shout – “Can you get out here, Sir?”. The fellows had got on the top from the trench and had lifted the sandbags and the battens off. I was able to get down into the trench.

‘I went to look for the company commander, Captain Riley. Someone must have told him what had happened because he was coming towards me. He put his arm around my shoulder and said “My God, Endean, what’s happened?”. I told him, “Sergeant Ing ham’s in the dug-out – will you get him out?”. He sent me straight to the Medical Officer [Captain ‘Jack’ Roberts RAMC] at the Regimental Aid Post (in Railway Hollow). I remember thinking that I would kid the M.O. into giving me a drop of rum, but all I got was “Rum? You can’t have any rum, but here’s a tetanus injection!.

‘I wasn’t badly hurt. Just bits of shrapnel. After about four nights in hospital in France, I came to England. When I eventually got back to the Battalion I found that Sergeant Ingham had died from his wounds. If he hadn’t said “I’ll give you a hand, Sir”, he would have been here now.”‘

Sgt. Ben Ingham 15368 of Burnley, is buried in Euston Road Cemetery, Colincamps, Grave number ID 9.

b) Pte. Fred Sayer, sick and excused duties, volunteered to look after Z Company’s reserve bomb store. With two others he was in a dug-out ready to issue bombs when required. Nobody came. His two colleagues left the dug-out and Pte. Sayer was alone:

‘I had on a new wrist-watch, which I had received for my birthday in four days time. It was only a cheap ‘Ingersoll’ but it was my only contact with my family at that moment. Then I was aware that someone had joined me. He was one of the Brigade’s Cycle Company’s men. He said they were in the attack. He had not been in the trenches before and asked what he should do. He had come too far forward and had strayed from his unit. He was badly shocked at having this terrifying experience. I suggested that if he saw his company going past at Zero, he could join them, but he had better get down and wait or he wouldn’t join anything.

‘Suddenly there appeared hundreds of men coming past us. I looked at my watch. It was Zero. The men were coming over as if on parade, with bayonets fixed, but with rifles carried at the trail.

‘It was uncanny and unbelievable where everybody went. The German barrage was heavy and deadly and machine-gun fire from the flanks and front covered every inch of ground, killing and pinning down the entire attack almost before it had begun. Many shells were dropping and I flung myself down near the cyclist. Then, I was conscious of recovering from something. I had a lovely experience. I had ascended weightless into space with all the colours of the rainbow all around. I did not want to come back to earth. I could not hear anything, but there was an awful smell and my head was hot. I took off my steel helmet and a steel splinter which had penetrated the metal was burning the thick wool felt. I knocked it out and quickly put the helmet back on. I said something to the cyclist but he did not reply. I felt giddy and light-headed. How long I had been unconscious I had no idea. My mouth was dry, my eyes and nose were bunged up with gas-tainted earthy but it was not until I reached for my water-bottle that I realised that something was badly wrong. I was fall of blood and gore. I looked at my limbs, felt at myself all over, but all seemed there. The cyclist was there too, buried to the waist and looking to his front, as before.

‘Some of the water quenched my thirst and some helped to clean up a little. Then I realised that the bombs in the dump would not be required and I had wasted my endeavours. I was very tired. I was dazed, but I knew where I was and what I was detailed to do. I examined myself again and seemed o.k., but the bayonet on my rifle was broken off and the bolt had snapped although it fitted in metal grooves. As time passed our barrage seemed to weaken into nothing, but the Germans gave no respite and their heavies pounded the forward areas as well as the rear, where they probably thought our reserves would be forming.

‘Reasonable thought came and went. I dozed but did not sleep. Suddenly, in the late afternoon, for the first time that day, I was afraid. I realised, for the first time, I had been concussed. With the return to consciousness, I recovered the will to survive. But I was still weightless as if I was intoxicated. However, only then did I realise that since Zero hour I had been talking to the dead. Crawling the few yards which separated us, I examined my silent comrade. The poor lad had been killed by the same shell that concussed me. From the waist down there was nothing. His lower half appeared to be buried, but in reality he was upright on his stump. He was still looking towards the enemy, with his helmet at a rakish angle. His face was white but not care-worn and he had no blemish on any visible part. If he had a similar experience to my heavenly flight, I thought, he must have had a lovely death.

‘I now realised where the mess I’d been cleaning from my equipment came from. There was nothing I could do, except leave the cyclist as my silent companion. I’m sure he died painlessly. I remembered him being lost, it seemed a long time ago. He was very afraid and I was very sorry for him. It was a terrible crime to send people like him into battle without preparation or training. I was angry for him, not because of the war, or that I was in my present predicament, but because he should not have been there.’

c) Pte. Harry Fielding – prisoner of war

Pte. H. Fielding 24137

X Company, 11th E.L.R.

Kriegsgefangenen Stammlager Nurnberg,

Bayern, Germany.

Dear Aunty,

I hope that you received the post-card which I sent a week ago. I am doing nicely at present, my leg I think will soon be quite right and the doctor says my face is doing well Of course it is very painful, especially when I am having it dressed, but if it gets alright again I shall have to “keep smiling” The hospital people are most kind to us and the doctor seems to want to do his very best for everybody. The address only stands whilst I am in hospital, afterwards I will let you know my other address.

And now I suppose you will want to know how it happened. If ever anybody was looked after that morning I was. It was July 1st and before we went over the top, I had my ammunition pouch blown clean off my equipment and a hole through my tunic pocket as big as half a crown.

Pte H Fielding (Mr John Fielding

As soon as we got over my bayonet was broken clean off, with a bullet I fancy. Them I got hit with shrapnel in the leg (left). Afterwards, I must have been hit again but do not know when. Well, I got into a shell-hole and it was whilst I was taking potshots from there that I was shot through the face.

The bullet entered the left side, between the ear and eye and gashed the back and top of my mouth a little and left at the joint of my right ear, splintering my jaw-bone there. My chum bound it up as best he could but we could not stop it bleeding at my nose and mouth and I lay there until dark.

After dark I crept out and I must have gone round in a circle, because I found myself looking down the barrels of four German rifles, so I threw the sponge up. I was far too fatigued to crawl any further and they treated me very well. I shall never forget that day in that shell-hole but I think I have something to he thankful for that I am alive at all, another inch or so would have done it. The doctor takes the pieces of broken bone out and I think the face will get quite right in time. I can only eat sloppy foods yet and have had eggs and milk, rice, etc. with a few biscuits and jam and tea and coffee. My mouth is not quite as sore now but I cannot bite.

Besides some handkerchiefs I would like some cotton (to sew my trousers) and needles and a bit of wool to darn the socks, grey preferred, a few envelopes and a few sheets of notepaper, also a pencil, if this is not asking too much.

This is all for the present, so will close with love to you and all at ‘22’, also father. Kind remembrances to Miss Harwood and her mother and Mr. and Mrs. Bates. I can only write two letters per month now and one post-card per week. One other thing, Miss Mashiter of Hardman Street sent me a parcel just before we went into the trenches and I sent a field post-card and a promise of a letter. It’s impossible to write now, so will you drop her a line and explain things. Miss Harwood will understand that I cannot write to her.

Best of Love from Harry.

‘P.S. If Uncle John has an old safety-razor ask him if I can have it. I have neither money nor belongings.

Pte Fielding was twenty-one at the time of his capture. When he returned from Germany he resumed his work as an assistant with H. L. Baxter Limited, booksellers and music dealers, of Blackburn. (The Miss Harwood he refers to was another assistant.) Shortly before the Second World War he bought the business and ran it until his retirement in the 1960s. During the war he served in the Home Guard at Wilpshire, near his home in Salesbury, near Blackburn. He died in 1977, aged 82.

A group of British prisoners of war at Nurnberg, Bavaria in 1917. Pte Fielding is second from left on front row. Note the sabots. (Mr John Fielding)

d) Pte, Fred Say er – journey to the rear

On 4 July, the fear of counter-attack over, the remnants of the Pals withdrew to Rolland Trench, in the fourth line of the defences. Later in the day they were relieved by a company of the 6th Gloucestershire Regiment of 144 Brigade, 48th Division. The broken battalion retired to Louvencourt to rest. Some individuals, such as Pte. Sayer, made their own way back:

‘On 4 July, which was my nineteenth birthday, we were told we were going to Louvencourt, where Z Company headquarters was now based. I asked Captain Heys, our only surviving officer, if I could leave early and go overland. I think he thought I was barmy but said he would he grateful if I could make it somehow.

‘I have made that journey a thousand times since and I still recollect every minute and every yard of the trail which started at two in the afternoon and finished around midnight. The previous day’s rain rendered the remains of the trenches too difficult for me to negotiate, so saying “Cheerio! “ to my comrades and with a “Good Luck” from Capt. Heys, I left.

‘An age later, after working from shell-hole to shell-hole, taking any cover available, I came into the open world. As I passed the remains of the ‘Sucrerie’ on my left, I came to green fields, with gun emplacements to be out-flanked and avoided, A few ‘heavies’ were passing overhead, making a noise like a goods-train as they went on their way to the rear areas. Suddenly, a shell screamed down at me, landing with a hefty thud about fifty yards to my right. I flattened out, but it didn’t explode. Deciding that it wasn’t for me, I looked down the hole it had made in the ground. It was a nice clean hole about twelve inches across, with the sides sliced by the spin of the shell.

‘Just before I reached Colincamps I met two or three platoons of troops. They were moving along in single file and all looked at me. They were all shaved and polished and I felt their sympathy and kindness as we passed on our respective ways.

‘Colincamps had been knocked about but the old Brigade H.Q. was still there. I went inside and there was a telephone or signals orderly on duty. He gave me a drink of tea and a chair to rest awhile. Outside I examined my clothes and equipment. The only thing that was clean was my rifle and my leg (which showed through a large tear in my trousers). The rest of me was disgusting. It was remarkable how lice breed in a few days.

‘Against the wall of HQ was an army bicycle and knowing there was a long incline on the road to Courcelles, I took it along. Out of the village, I thought that I could free wheel for about a mile and this would be helpful as I could not pedal It was jolly to be off my feet, and a delightful feeling to be moving without any effort until, I think, I fell asleep. I ‘came to’ sitting in a deep ditch full of water and greenery and when I sorted myself out, I felt a little cleaner. I left the cycle in the ditch and proceeded on my weary way.

It was an involuntary action that took me along the roads through Courcelles, Bertrancourt, Bus, then to Louvencourt to Z Company H.Q. I developed into a perfect introvert. Although I was moving steadily towards my goal, I felt tied to a taut but constraining, invisible force which held me back. In fighting this negative force I completely ignored any help. I passed several military units where I could have obtained help and refreshments. The darkness intensified the feeling and instinct alone kept me on the right track to Louvencourt.

’suddenly I was surrounded by men from H.Q. who were waiting to guide us to billets. They took my rifle and equipment and led me into a barn which had several storm-lamps burning and straw on the earthen floor. There were blankets. I don’t remember eating any food, but I well remember tea – I drank and drank. I, or someone, stripped off my uniform, or what was left of it, and I was down on a glorious bed. It was fresh straw purchased from the farmer by H.Q. (the first time they had ever done this for us). No four-poster bed with eider-downs and all the glories of the castle bed-chamber ever had a more appreciative sleeper than that humble straw had. I slept for nine hours.

‘When I awoke about twenty others were there. We were given breakfast in bed, or at least where we had slept. The barn doors were open and the sunlight streamed in. All was peaceful. Nobody spoke. There were no N.C.O.s or officers. Gradually we eased ourselves outside. We quietly washed ourselves down, then sat on the barn foundation stones to scrape the mud and grime of battle from our equipment.

‘It was a sober moment for all of us. About one in five of us were left and many of these, like me, were not fit for duty. We talked quietly, trying to ascertain what had happened. We had trained together for nearly two years and someone had messed things up and we had paid the price. There was much sadness at our failure and, for once, “humour” – that paragon of the British Army – was absent.’

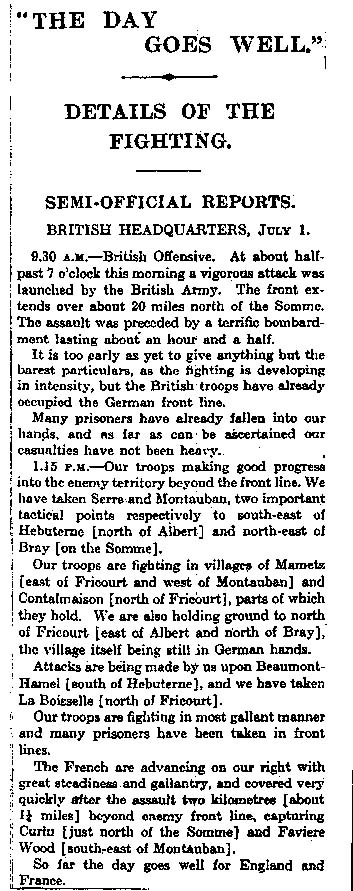

The first reports of the attack raised false hopes to people at home, The Times, 3 July 1916. (The Pals Collection)

Present day Colincamps, looking east. The war memorial and church. (The Pals Collection)

On 6 July the survivors of the Battalion marched from Louvencourt to Gezaincourt where they stayed two days. Percy Crabtree found time to sketch his billet. The 1998 scene is much changed apart from the tower.

On 6 July the survivors of the Battalion marched to Gezaincourt where they stayed two days. L/Cpl Crabtree found time to paint his billet.(The Liddle Collection)

The 1998 scene is much changed apart from the tower. (The Pals Collection)

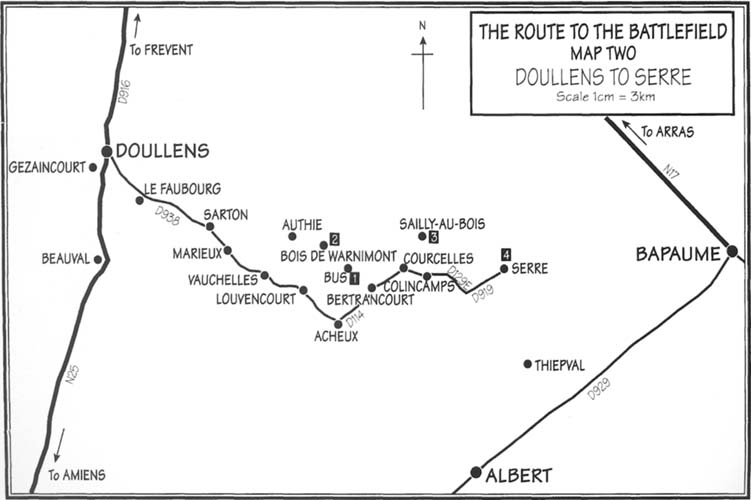

Following the Trail

Private Sayer’s journey to Louvencourt can be followed by car. The most practical start-point is where the D919 Mailly – Maillet to Serre road crosses the D28/D174 Hebuterne to Auchonvillers road. The ruined sugar-beet refinery (the Sucrerie) which marked the entrance to 94 Brigade’s trench system was nearby. ‘I passed the remains of the Sucrerie to my left’.

Some 300 yards (275 metres) to the left of the crossroads is Sucrerie Military Cemetery. The approach is by a long, narrow, track, just wide enough for a car. There are 894 graves, of which four are of Pals. Two, Private Clarke and L/Cpl. Hartley, were buried on 29/4/1916, the first Pals to be killed in action. Pte’s Jackson and Pickering were killed by accident a month later (see page 30).

Private Sayer would first go towards Colincamps along the D174, Hebuterne, road before bearing left onto the D129E. On the roadside to the left would be the site of Euston Road Cemetery. A light railway then ran nearby bringing supplies to the front-line at Railway Hollow. (When 2/Lt. Bart Endean arrived at the Battalion in April 1916, his first job was to organise the construction nearby of Euston Dump, after which the cemetery was named). The cemetery now contains 1261 graves, many of which were concentrated there after the war. There are 26 Pals, all killed in action on 1/7/1916.

In Colincamps is the Mairie, now rebuilt, in which, in 1916, was 94 Brigade HQ. It was from outside this building that Private Sayer ‘borrowed’ the bicycle. Near the junction with the D129 Sailly-au-Bois road are barns and farm buildings which, in 1916, were used as billets. At the junction turn right, then left, onto the unclassified road which goes directly to Courcelles. In 1916 the right hand side of the road was strung with camouflage nets to hamper the observation by the enemy of troop movements. If one looks towards Serre and the old front line one can understand why they were necessary. It was down this road that Private Sayer free-wheeled on his borrowed bicycle.

On entering Courcelles, bear left onto the D114 road to Bertrancourt. (Just to the right, on the road to Sailly-au-Bois, is the Communal Cemetery and Extension. Of the total of 115 war graves there is one Pal – Private Taylor – who died of wounds on 13/11/1916). Go through the village and on to the straight road to Bertrancourt. At the village, turn right onto the D176E road to Cogneux. As the road leaves Bertrancourt, turn left on to the D176. About 400 yards (365 metres) west of Bertrancourt is Bertrancourt Military Cemetery. 416 men are recorded in the register, of whom there are 13 Pals who died in June 1916).

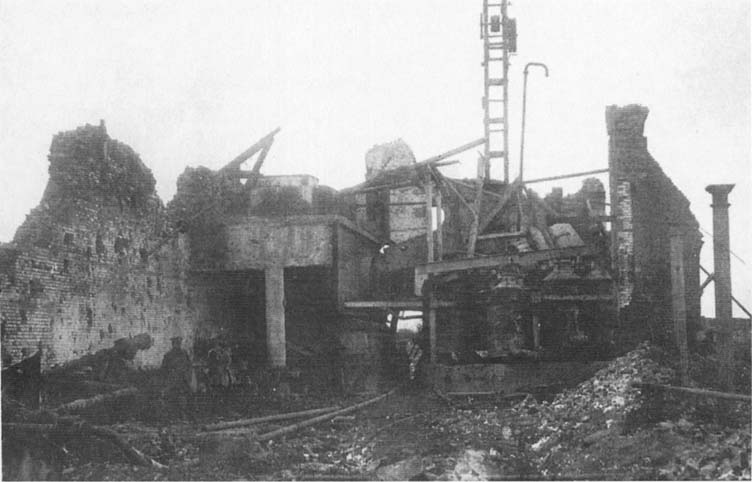

‘I passed the remains of the Sucrerie to my left’, Fred Sayer’s journey to the rear. (The Pals Collection)

The D176 is a short, winding road leading into Bus-les-Artois. Behind the church is Bois du Bus (Bus Wood), in 1916 the site of a hutted encampment. In the centre of the village turn left onto the open, unclassified, road to Louvencourt. It was at the entrance to the village that the HQ staff were waiting to lead Private Sayer and other survivors of the failed assault, to their billets in the ruined barn.

It is estimated that the total length of Private Sayer’s walk from the front line, through Colincamps, Courcelles, Bertrancourt and Bus-les-Artois to Louvencourt was something like nine miles – say fifteen kilometres. His journey time then was approximately ten hours.

Walks (and car tours) around the area of the Serre battlefield are extremely well covered in a special chapter (pp 103 – 136) of Serre, by Jack Horsfall and Nigel Cave. One of the Battleground Europe series, this is published by Pen & Sword Books, (1996).

Another useful book is Walking the Somme, by Paul Reed (same publisher, 1997), in which the area is described in more general terms as part of a guide for those touring the battlefields on foot.

4. Casualties and Awards

CASUALTIES

Nine officers and 228 men were killed as a result of the attack. As far as is known, twelve officers and 339 men were wounded. At least seventeen men died of their wounds in the weeks following. This brings the total of 254 officers and men who died, and 351 wounded, to 605.

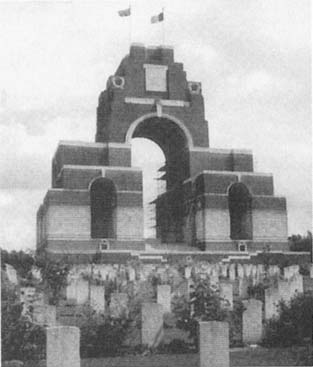

136 of those who died are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. 118 are buried in a total of fifteen cemeteries in France and England. 50 lie in Queen’s Cemetery, Puisieux; 24 in Euston Road Cemetery, Colincamps; 15 in Railway Hollow Cemetery, Hebuterne; 6 in Serre Road Cemetery No.3, Puisieux and 3 in Serre Road Cemetery No.2, Beaumont-Hamel. There are one each in Beaumont-Hamel British Cemetery and Serre Road Cemetery No. 1, Hebuterne. 15362 Pte. Arthur Dent lies in Tilloy British Cemetery, south east of Arras. He was, presumably, captured by the Germans and died of his wounds

Serre Road Cemetery No 2, Beaumont Hamel, Hebuterne. A view from the rear. (Mr Bob Curler)

The Thiepval Memorial. (Mr Bob Curley)

Of the seventeen men noted as ‘died of wounds’, five were buried in Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension; two in Beauval Communal Cemetery; two in St. Pol British Cemetery, and one each in St. Sever Cemetery, Rouen and Etretat Churchyard, near Le Havre.

In England, five men who died in English hospitals lie in Accrington Cemetery and there is one man in Padiham Cemetery, near Burnley. In all a total of 254.

It cannot be said precisely how many died or were wounded as a result of 1 July. For those killed in action and died of wounds the above figures are based on the registers of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The figures for those wounded are from the Battalion War Diary. No count can be made, of course, of those who died as a result of their wounds anything up to twenty or more years later. Therefore these figures must be considered as minimal.

The casualties sustained by the Battalion as a result of 1 July 1916 were the largest ever suffered in any action. This experience changed the Battalion from a local, almost parochial, unit of inexperienced enthusiasts to a battle-hardened force equal to, if not better than, many infantry battalions on the Western Front. Thus they served, always with gallantry and honour, throughout the rest of the war.

Even the totals on Thiepval Memorial must be considered as minimal. The name of 17840 Pte. Joseph Riley of Church, was added in 1998.

AWARDS

As far as is known one Military Cross, three Distinguished Conduct Medals and three Military Medals were awarded for acts of bravery on 1 July.

Lt. Thomas William Rawcliffe was awarded the M.C. for his deter-mination and coolness when bringing four trench mortars into position through a very heavy barrage.

15183 C.S.M. Arthur Leeming handled his company with great coolness and skill when all his officers became casualties.

15961 L/Cpl Esmond Nowell, although wounded, delivered a message to H.Q. through heavy fire and then returned to his company. Nowell later won the Military Medal whilst serving with 2 East Lancashire Regiment.

17992 Pte. William Warburton single-handedly attacked an enemy bombing party in a German communication trench. He killed an officer, wounded others and caused the remainder to retire. All the above men were each awarded the D.C.M.

The following three men were awarded the M.M.:

18048 Pte. Stanley M. Bewsher reached a German communication trench and fired his Lewis gun at a group of the enemy forcing them to retire. When his own gun was damaged by shellfire, he picked up another and continued his attack.

15657 Sgt. Austin Lang was killed whilst leading his men, after his officers became casualties, in the attack on the enemy trenches. (awarded posthumously). Sgt. Lang’s body was never found or identified and his name is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. 24139 Pte. Holford Speak, although wounded, left the safety of a shell hole to assist a wounded comrade. He was immediately wounded a second time but both he and his comrade were able to return to their own lines.

5. Re-organisation of the stretcher-bearers – July

Later in July Pte. Sayer was informed by Major Kershaw (newly promoted) that he was to train the Battalion’s new stretcher-bearers.

‘“I can’t do it, Sir, I’m a bomber”. “Nonsense!, I know you were a doctor’s pupil before you enlisted. You used to treat my wife’s mother in Burnley. If you can do that you can teach first-aid.”‘

On that slender basis, Pte. Sayer became L/Cpl. Sayer, Medical Orderly, with responsibility for thirty-two stretcher-bearers.

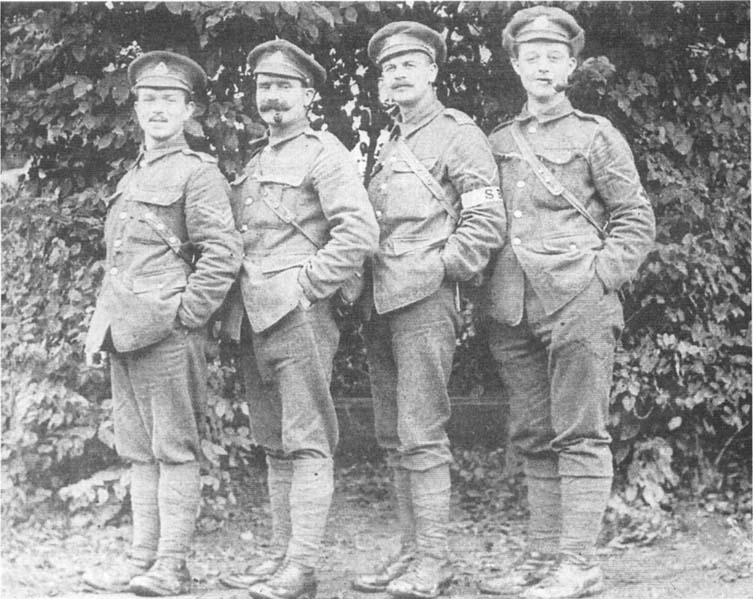

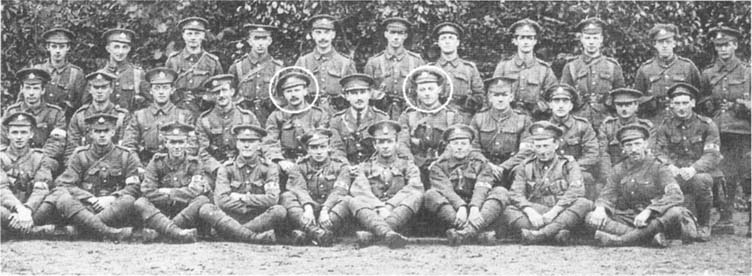

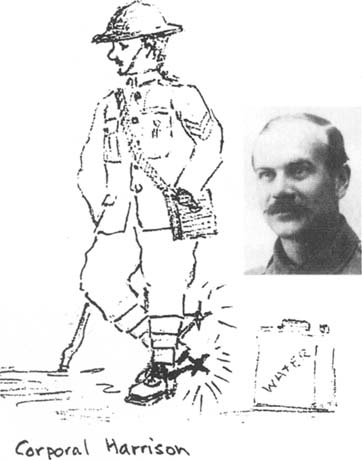

Cpl Harrison (i/c water), Pte Webster (MO’s batman), L/Cpl Crabtree and L/Cpl Sayer. Photograph taken in France 1916. (Mrs J Lamgton)

Pte. Percy Crabtree was a volunteer. Fred Sayer interviewed him:

‘My enquiry as to first-aid brought the reply “Teachers need to know a little”. I promptly accepted him. At my suggestion, Percy was given a stripe and put in charge of the stretcher-bearers.’

‘Percy Crabtree was a product of his own efforts which gave him college training and ten years teaching experience. He was a delightful fellow, quite unsuitable for army life, but fitting in and making the best of every situation. He had lots of patience, a subtle sense of humour, a love of music and he was a painter in water colours. His job now was to organise the stretcher-bearers.

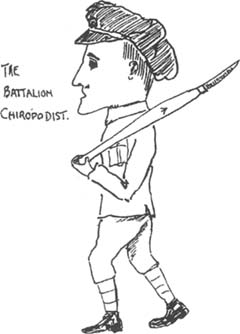

‘Captain Anglin, a Canadian, our Medical Officer, was responsible for the health of the Battalion and was supposed to keep an eye on food, water and sanitation. I, as Medical Orderly, was responsible for the sick and wounded, organising the movement of equipment and supplies to and from the line and for the training of the stretcher-bearers. There was a Sergeant Cook, a Water Corporal, a Sanitary Corporal, a Chiropody L/Cpl. and a Stretcher-Bearer L/Cpl. Apart from the latter, the rest did not concern me, except that the Water Corporal and the Chiropodist joined the M.O.s batman and attached themselves to our squad.

‘This was the gathering together of a group based on mutual support in feeding, entertainment and morale, although Percy’s singing and harmony might have been the attraction. We became very fond of a little singsong, much to Percy’s delight.’

The stretcher bearers and medical staff. L/Cpl Sayer is on the Medical Officer’s left, L/Cpl Crabtree is on his right. (Mrs J Langton)

Sketches by L/Cpl Crabtree.(The Liddle Collection)

6. Thoughts on trench names – Percy Crabtree

‘We marched from Warnimont Wood to Colincamps and the front line. It was Monday – washing day in the French villages evidently as in Burnley. But what a day! A fine drizzle finished up as pouring rain, and we were well soaked as we filed down Du Guesclin trench, along Jean Bart to the front line, the left flank resting on John Copse of ill-omen.

‘Here were some old trenches named by the French when they held this line in 1915. Vercingtorix – an old Gaulish chieftain who fought the Romans almost to a standstill, but was later captured to grace a Roman triumph in the Eternal City. Du Guesclin – a famous old French knight who grimly fought the English on this same soil several centuries ago. Jean Bart – pirate and privateersman, who harried English shipping in those years of interminable warfare when France was the old enemy. Oddly enough, we were all glad to have the shelter and protection of old Jean Bart, reprobate though he was, in our journeys to the front line.

‘How different were the English in their naming of trenches and how significant of the temperamental and racial differences between French and English. The Battalion occupied Blind Alley, Jam Street, Pub Trench – all in this area. Nothing to rouse the martial spirit there, like Jena a communication trench named after one of Napoleon’s greatest victories.

‘Only the profane and sacrilegious English could have named four small copses after four apostles – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.’

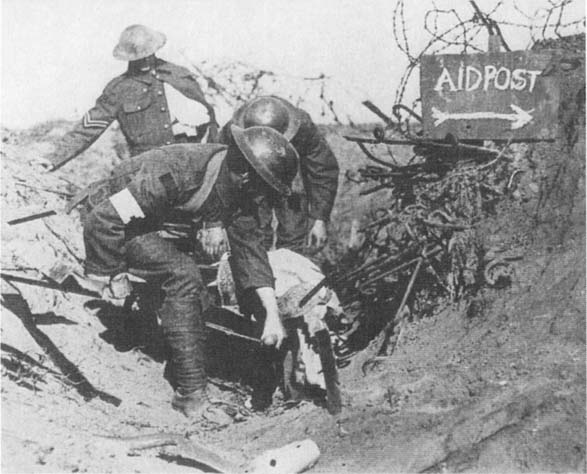

7. Bitten on the Bottom – by Fred Sayer

‘This part of the line was supposed to be a quiet one. One day, however, the Boche sent over some heavy stuff onto a working party in a communication trench and they buried the party with the first salvo. It was a ghastly business and it turned the head of the Sergeant Major in charge. He went berserk and was going towards the Boche line with bayonet fixed, when someone grabbed him. He was brought to the Aid Post along with many badly wounded. The little place was full to overflowing, and there was a great commotion with the S.M. trampling over wounded men trying to “get at em”. He was just above me and I saw he was just plain crazy, so I hit him on the jaw and he quietly subsided across a poor fellow lying on a stretcher.

‘I was sitting on an improvised cot which already contained a badly wounded man, but I managed to push him over and put the unconscious S.M. alongside him. I then sat on the S.M.’s chest and carried on applying first aid and writing labels, so that lightly wounded could get away. Suddenly 1 was bitten on the bottom. I nearly jumped through the roof. Fortunately khaki uniforms are quite thick but the S.M. had a good voice and some hefty teeth. I dare not knock him out again, so I rendered him harmless by tying up his arms and his legs.

Battalion stretcher bearers take a casualty to the Aid Post. (The Liddle Collection)

‘It was hours before we got back to normal and as the last of the wounded was carried away we stretcher-bearers gathered at the Aid Post. The heavy pressures had left us all limp and weary. Suddenly someone said “What about your wound, Corporal?” There was a silence, then – “He’s been bit in the backside by the Sergeant Major!” The tension departed as everyone roared with laughter and demanded I had my stern cauterised. it was a merry five minutes of real army humour which ended in comments of what would happen to me when I was court-martialled for knocking out a warrant officer. Tears flowed because of the hilarious situation, laughter came easily and was welcome as a relief valve.’

8. Hot Tea – by Fred Sayer

‘The situation was crazy. We had nothing but our hands (usually frozen) and sandbags to help half-frozen wounded survive a wait of perhaps four hours before they reached the field hospital. I suggested to the M.O. that there should be hot drinks of either tea or meat extract for the sick and wounded. He looked a little suspicious and said “Its not laid on, but what do you suggest?’’ “Leave it to me, Sir!”.

‘Off I went to see the Quarter Master. I knew him in Civvy Street and waited for him to be alone. I sort of claimed privilege and talked to him on equal terms. All I had to do was to dramatise the case of one man, whom we both knew, who had just left us, wounded, cold and weary. He said, “It’s a matter of supplies.” I suggested that it was worth it if all the HQ staff had to do without tea, but we had lost thirty men in our last spell and he was still drawing their rations. The Q.M. had no answer to that and suddenly there was no problem. I left with two full sandbags, one tea and one sugar, plus tins of milk.

‘What a blessing! And also given with the blessing of the Quarter Master, which meant that future supplies were assured.

‘I am sure this humble treatment saved many lives. The joy a wounded man showed when given a hot drink was unbelievable. The stretcher bearers, whose job was a pretty tough one, needed to be revived and often a hot drink made possible another trip. We in the Aid Post enjoyed testing each drink to see that it was not too hot. We could not afford to let our spirits flag.’

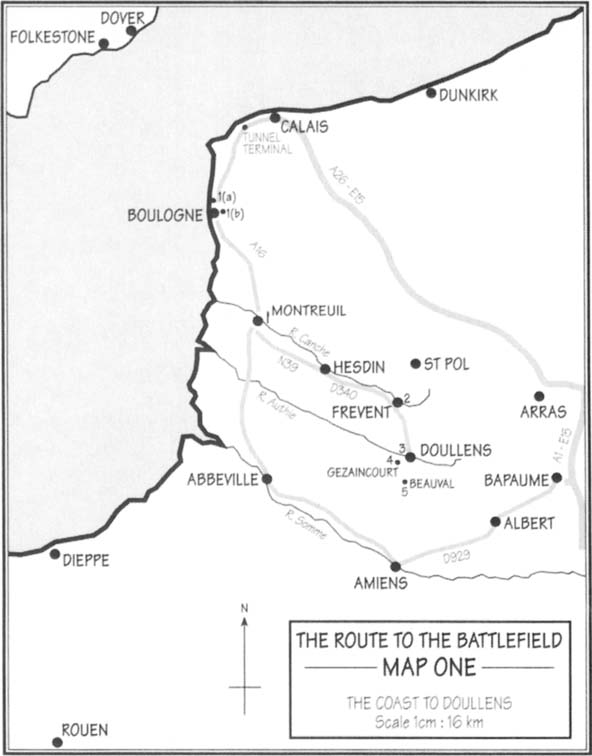

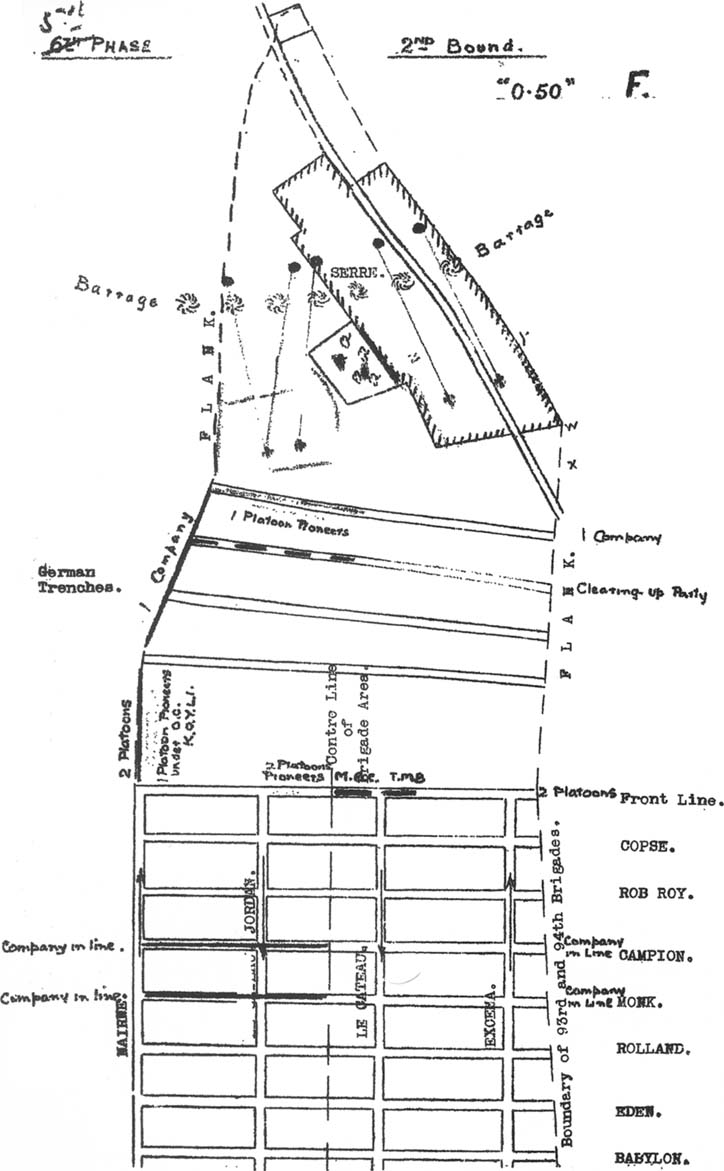

9. Following the 1916 Trail of the Pals

Most British visitors to the Somme battlefields arrive in France either at Calais ferry terminal or the Channel Tunnel terminal. There is then a choice of routes. Firstly, via the Paris A26-E15 Autoroute past Arras, then to Bapaume on the A1-E15 (junction 14). Secondly, there is the A16 Autoroute to Amiens, thence to Albert on the D929.

If one has the time however, the drive from Calais or Boulogne to, and through, the towns of Montreuil, Hesdin, Frevent and Doullens and from there through the rear areas of the old front line is relatively pleasant. It is also much more rewarding because from Doullens one follows the trail of the Pals to Serre through the villages and countryside with which they were familiar in 1916 and 1917.

A personal choice is to take the N1 towards Boulogne, then continue on the N1 to Montreuil. From there take the N39 to Hesdin. This road goes through the very pleasant, and quiet, valley of the River Canche. From Hesdin continue along the valley on the D340 to Frevent. This brings one to the D916 and onto Doullens. Doullens was an important base throughout the war. Its position well behind the lines, at the meeting of roads from St. Pol, Arras, Amiens and Albert made it a very important transportation centre.

On the drive to the battlefield it may be appropriate to consider several detours, which could be included in a personal itinerary, (see map 1)

1. Boulogne

(a)Two miles north of the town Is Terlincthun British Cemetery, Wimille. The cemetery contains the graves of men and women who died of wounds or sickness (mostly influenza) in nearby hospitals. The cemetery is still ‘open’, in that it is used for the burial of bodies still found on the old battlefields of France. Twelve Pals are buried here. Eight died of Influenza, or its complications, whilst four died of wounds. 15860 Pte. Andrew MacGrath, who caught pneumonia after celebrating the Armistice, died on 21 November 1918. His grave is in Plot X1 Row C Grave 26. Nearby in X1 C32 is 2/Lt. Mark Thomas Washbrook who died on the same day from wounds sustained on 18 October 1918 at Wattrelos, near Roubaix.

(b) On the high ground overlooking the town is Boulogne Eastern Cemetery. The register records 5,578 burials. Three Pals who died of wounds in local hospitals are here. One died in November 1916 and two who were wounded near Hazebrouck at the end of April 1918.

2. Frevent

The Communal Cemetery of St. Hilaire is on the eastern side of the town. Here are three Pals who died of wounds sustained at Ayette in the German March 1918 Offensive. They were amongst the last to be buried in the cemetery before the Extension was opened.

3. Doullens

Up to April 1918 men who died of wounds at the Casualty Clearing Stations based in the medieval Citadelle were buried in an Extension (No. 1) to the nearby Communal Cemetery. Five Pals, all but one wounded on 1 July 1916, lie here.

4. Gezaincourt

Between Doullens and the village is Gezaincourt Communal Cemetery and Extension. There are 590 graves in the Extension, one of which is of 15505 Pte. Percy Hargreaves who died of wounds on 26 June 1916. From 5 to 13 June 1916 the village was the scene of full-scale Brigade rehearsals for the 1 July attack.

5. Beauval

Beauval is a large village four miles (6.5kms.) south of Doullens on the N25 road to Amiens. The Communal Cemetery is on the northern side, at the end of a cul-de-sac. Four Pals are buried here. Two died of wounds received on 1 July 1916 and one died of appendicitis on 26 May. 20927 Pte. Arthur Riley, who died of wounds on 30 April, lies in grave E7. He was the first Pal to die on active service in France. After living in Rhode Island, U.S.A., for several years he returned to Accrington in July 1915 to enlist.

Sarton Church as painted by L/Cpl Crabtree during a halt on the march in 1916. (The Liddle Collection)

Sarton Church in 1998.(The Pals Collection)

Continuing from Doullens, turn south onto the N16, the Amiens road. On the outskirts of the town turn left onto the D938, sign-posted to Albert. This road follows the very picturesque valley of the River Authie. This is a pleasant run, in complete contrast to the busy N16. This quiet road passes by numbers of roadside bungalows and small houses, many with gardens, until one reaches the appropriately named hamlet of le Faubourg ( the outskirts), some two and a half miles (4kms) from Doullens. From there to Sarton it is three miles (5kms.).

As with most villages in the area there is a peaceful, almost lethargic, air about Sarton. This is in contrast to the war years, when it was at an important road junction in the rear area. It was in constant use as billets and as a depot for line of communication troops. It also served as a resting place for troops going to and from the front line. The D938 continues past Vauchelles-les-Authie to Louvencourt, thirteen miles (21kms.) from Doullens.

On 1 July Louvencourt was six miles (11kms.) behind the front line. It was here, on 4 July, that the survivors of the Pals assembled after the battle. Just at the end of the village a narrow unclassified road (easily missed) meets the D938. Down this road, on the left, is Louvencourt Military Cemetery.

This is the first ‘cemetery stop’ for many visitors en-route to the battlefields. There are seventy-five French and 151 British war graves. 2/Lt. Roland Aubrey Leighton of 7 Worcester Regiment who died of wounds on 23 December 1915, is buried in grave I B 20. Primroses mark the grave. 2/Lt. Leighton was the friend of Vera Brittain, the author of Testament of Youth, a classic memoir of the period. Also here, in grave I F 9 is Brigadier General C. B. Prowse, Commander of 11 Brigade, 4th Division, the most senior officer to be killed on 1 July 1916. There are no Pals in this cemetery.

Follow the D938 to the larger village of Acheux-en-Amienois. In 1916 Acheux was a forward base and railhead for much of the matériel needed for the front. 8 Corps Walking Wounded Collection Centre was here and Ambulance Trains used the station to take wounded to Doullens.

Turn left onto the D114 to Bertrancourt, three miles (5kms.) to the northeast. In the months before 1 July the village was used as billets for the Pals and other troops whilst in 31st Divisional Reserve. A Main Dressing Station was based here. Some four hundred yards (365 metres) up a narrow lane is Bertrancourt Military Cemetery. Twelve Pals killed during the last tour of duty in the front line before 1 July (19 to 24 June) are buried here. 16043 Pte. Arthur Nutter, who died in a training accident on 17 June, lies in grave I D 18.

From Bertrancourt it is a short drive to Courcelles-au-Bois. From March to June 1916 the village was used by the Pals and others as billets when in 94 Brigade Reserve. The Mairie (the Town Hall) became Battalion HQ Courcelles was therefore in constant use as an assembly point for battalions on their way into, or out of, the front line. The whole area was full of British artillery positions and consequently was the target for German retaliatory shellfire. On 1 July 1916 the village was the site of 31st Division HQ

The Communal Cemetery and Extension is on the northern edge of the village at the junction of the unclassified road to Coigneux and the D114 to Sailly-au-Bois. The Extension was started in October 1916 and used until March 1917 and again in 1918. 29479 Pte. Edgar Taylor, who died of wounds received near Hebuterne on 13 November 1916, lies in grave C 7. (Pte. Taylor was one of forty men who died during the period 19 October 1916 to 18 March 1917 in the Battalion’s tour of duty in the nearby Hebuterne/Sailly-au-Bois sector).

The Mairie in Courcelles. (The Pals Collection)

Just before the cemetery, however, a narrow unclassified road, signposted to Colincamps, turns sharply to the right (another easily missed). The road rises over open ground. In 1916 there was a screen of camouflage netting alongside the left side of the road. One understands why when one considers the numbers of troops using this road to and from the front line, and the open view of the area from the German front line at Serre and beyond.

It is just over half a mile (1km.) to Colincamps. The village, like so many others in the area, is quiet, with an almost deserted air. During the war however, it was completely destroyed. It was, in 1916, well known to the Pals. It was the last village before going into the trenches before Serre. 15139 Pte. George Pollard, then seventeen, remembered his first visit ‘We were in a barn, with tiers of wooden bunks. We walked about the streets, gazing round at the wreckage. We thought how wonderful it was to be at the Front’.

The barn is in the farmyard on the left as one enters the village on the road from Courcelles. The Ecole (School) was used as Battalion HQ during their stays in the village. (In 1920, Burnley, home town of Z Company, adopted Colincamps and Courcelles and helped finance the rebuilding of the villages).

Continue out of Colincamps down the D129E (signposted to Auchonvillers), to Euston Road Cemetery, half a mile (800 metres) on the right. The cemetery was used during and after the 1 July battles. The register records 1,261 names, of which twenty-six are Pals. All were killed in action on 1 July.

Continue to the junction with the D919 at la Fabrique Farm. This is the site of the Sucrerie from which troops going into the front line entered the trench system. On the Mailly-Maillet side of the D919 is the access road to Sucrerie Military Cemetery. There are 894 graves here, four of which are of Pals. Two died in April 1916 and two were killed accidentally in May.

When returning from the cemetery, turn left onto the D919 towards Serre and Puisieux. Along the road to the right is Serre Road Cemetery No.2. This is the largest cemetery on the Somme, with 7,139 graves. Three Pals are of this number. Whilst continuing towards Serre one comes to the French National Cemetery on the left. Nearby is Serre Road Cemetery No.1 24514 Pte. John Winter is buried in grave V C 9. The original cemetery was made in 1917 and was greatly enlarged after the Armistice by the concentration here of bodies found in different parts of the battlefield. Pte. Winter would be one of these.

On leaving the cemetery turn left towards Serre, but turn left almost immediately where a C.W.G.C. sign directs visitors up a track to the Serre battlefield. Serre Road Cemetery No.3 is at the top of the slope. It is in the open field on the site of the German front line. Eighty-one men lie here. Six are Pals who died on 1 July.

Continue along the track across the old No Man’s Land to Mark Copse. This is the place from which the Pals advanced on 1 July. The Accrington Pals Memorial is just behind what was then the second line trench (the first line trench was filled in many years ago). There were originally four copses – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – but Matthew Copse was ploughed over after the war.

Behind Mark and Luke Copses is Railway Hollow Cemetery. The Cemetery is on the site of the Regimental Aid Post used on 1 July. Fifteen Pals are buried here. In common with many cemeteries on the Somme – and indeed the Western Front – there are also graves of men ‘Known unto God’. These are men unidentified at the time of burial. 73,357 such men died in the Somme battles between July 1915 and March 1918. Their memorial at Thiepval names 145 Pals.

Serre Road Cemetery No. 3. (The Pals Collection)

As one returns to the British front line past the memorial shelter of Sheffield Memorial Park, there is a path across the field to Queen’s Cemetery. There are 312 graves, fifty of which are of named Pals. All the Pals died on 1 July but were not buried until the cemetery was formed in May 1917.

It is here that this Trail must end. If by a miracle any Pals got into Serre village nothing is known about them. The few prisoners taken by the Germans appear to have been picked up in No Man’s Land after the attack failed. It seems appropriate, therefore, that this journey to the

battlefield ends at this place, the furthest the Pals advanced that day.

In common with the first part of the journey, several detours can be made if time permits:

1. Bus-les-Artois

The village is on the D176 some one and a quarter miles (2kms.) northwest from Bertrancourt. (There is an alternative way, slightly longer, from Louvencourt, along an unclassified road). Bus is a quiet, pleasant place, in a well wooded valley. The Bois de Bus (Bus Wood) is on the northern edge of the village. In 1916 there were hutted camps in the wood. These were used as a rest camp and a base for working parties. There is no trace now that hundreds of men were billeted here at any one time. The wood is privately owned.

Mark and Luke copses and the Sheffield Memorial from Queen’s Cemetery. (Mr Bob Curley)

2. The Bois de Warnimont (Warnimont Wood)

The wood is alongside the D176 on the way from Bus to Authie. In 1916 the wood was full of huts and tents. When newly built in the Spring of 1916 it was described as ‘an idyllic setting’ but it rapidly became very muddy and unpleasant. The Pals were here when in Divisional Reserve. Pte. Pollard described their accommodation as ‘wretched, with neither doors nor windows, nor beds to sleep on’. It was from Warnimont Wood, on 30 June, that the Pals began their seven mile march to the trenches at Serre. They used the woods again as a rest area during the months from October 1916 to February 1917 in their second tour of duty in the area. There is now no trace of any military occupation. This wood is also privately owned.

3. Sailly-au-Bois

Sailly is on the D114 just over a mile (2kms) northeast of Courcelles. It is a similar distance on the D129 from Colincamps. During the Somme battles the area was full of artillery positions, and the village was eventually destroyed by German shellfire. During their second tour of duty on the Somme, from October 1916 to February 1917, the Pals used a hutted camp in Sailly Dell, on the western edge of the village, when out of the line. Sailly-au-Bois Military Cemetery is also on the western edge of the village, on the D23 to Bayencourt. The cemetery was begun in May 1916 and used by Field Ambulances until March 1917. It was used again in 1918. The register records 239 burials, of which twelve are Pals. Five died in November and seven on 31 December 1916.

(The Liddle Collection)

The church at Sailly-au-Bo is in 1916 and 1998. (The Pals Collection)

4. Serre

The tiny village of Serre is on the D919 road from Mailly-Maillet to Puisieux which is a mile and a half (2.5kms.) to the north. Serre is smaller now than it was in 1916. Its position on relatively high open ground helps to explain how, and why, it was so strongly held by the Germans against every attack. Three major attempts to take Serre failed. The first, by French troops in June 1915, cost them approximately 2,000 men killed and 9,000 wounded and missing. The second attempt was on 1 July 1916. The third, in which the Pals also had a role, was in November 1916. These three attacks on this village of such strategic importance cost an estimated twenty thousand men killed, wounded and missing.

Serre was never taken. The Germans evacuated it, in their own time, on 24 February 1917 when they moved back to ready-made positions in the Hindenberg Line.

Useful maps are:

1. Michelin Carte Routiere et Touristique No. 236 Nord Flandres – Artois – Picardie 1/200000 – 1cm.: 2km.

2. Cartes I.G.N. France (Institute Geographique National).

Serie Bleu 23.07 est Doullens

24.07 ouest Bapaume

24.07 est Bapaume.

1/25000 – 4cm.: 1km.

General view of Serre village. (The Pals Collection)