2

THE JOURNEYMAN

Mixing with the world has a marvelously clarifying effect on a man’s judgment.

—Michel de Montaigne, “On the Education of Children” (1580)1

I must be cruel, only to be kind.

Thus bad begins and worse remains behind.

—William Shakespeare, Hamlet, act 3, scene 4, 177–78 (1600)

Formally initiated into the brotherhood of executioners, the nineteen-year-old Frantz Schmidt could now begin building the professional résumé that might one day secure him a permanent position. Shortly after his professional debut in Steinach in June 1573, the young journeyman was called to the town of Kronach, halfway between Bamberg and Hof, to administer his first execution with the wheel. His recording of the occasion is terse, as was his habit during these journeyman years. We learn only that the robber in question, one Barthel Dochendte, was guilty of at least three murders with his unnamed companions, and that his painful final ordeal was preceded by the uneventful hanging of a thief—a double execution and thus another first for the novice executioner. The young Schmidt does not in any way commemorate these novel professional experiences, at least not in writing.

Assisted by his father, Frantz secured an impressive total of seven commissions during his first twelve months on the job. Most of these involved the execution of thieves with the rope, all described by Frantz in succinct and emotionless terms. Hanging was a relatively simple, albeit grisly operation: the young executioner mounted a double ladder with the poor sinner, then simply pushed his victim off. Some jurisdictions used stepstools or chairs, but the platform with the trapdoor did not make its appearance anywhere in Europe before the late eighteenth century. Thus there was no sharp drop to break the neck, but rather prolonged choking, which might be accelerated by the executioner or his assistant pulling on the legs of the convulsing victim, typically wearing special gloves made of dog leather. Once the desperate struggle for survival came to an end, Frantz removed the ladder and left the executed corpse hanging on the gallows until it decayed and dropped into the pit of bones below the gallows.

Three of Frantz’s assignments during his first year involved execution with the wheel, an extended procedure requiring a much greater degree of physical and emotional stamina on his part. It was also the most explicitly violent, even gruesome act the young executioner would be required to carry out as a professional. Typically reserved for notorious bandits and other murderers, this method of final dispatch essentially consisted of public torture, akin to the more infamous—and also much rarer—drawing and quartering. But whereas the much more common interrogatory torture of the prison chamber ostensibly sought information leading to conviction or vindication, the very public breaking with the wheel aspired to no more than providing a ritualized outlet for the community’s rage and a terrifying warning to any spectators with murderous inclinations.

All three men Frantz executed with the wheel during his first year were multiple murderers, but only Klaus Renckhart from Veilsdorf, the young executioner’s seventh victim, merited more than a line or two in his journal. Sometime during the second half of 1574, Meister Heinrich arranged for his son to travel to the village of Greiz, about forty miles northeast of their native Hof. Upon the completion of his four-day journey from Bamberg, Frantz came face-to-face with Renckhart himself, convicted of three murders and numerous robberies. Their initial contact was likely brief, but during the last hour of the condemned man’s life, the journeyman executioner and his victim would be constant companions.

Immediately following the local court’s pronouncement of the death sentence, Frantz shepherded the shackled Renckhart to a waiting horse-drawn cart. During their slow procession to the execution site, Frantz administered the court-prescribed number of “nips” with red-hot tongs, ripping flesh from the condemned man’s arm or the torso. Frantz rarely comments in his journal on this aspect of the ordeal, but it could not have been more than four nips, which was commonly considered fatal. Upon their arrival at the execution scaffold, Frantz then forced the weakened and bloody Renckhart to strip down to undergarments, then lie down while the executioner staked his victim to the ground, meticulously inserting slats of wood under each of the joints to facilitate the breaking of bones. The number of blows with a heavy wagon wheel or specially crafted iron bar was also preordained by the court, as was the direction of the procedure. If the judge and jurors had wished to be merciful, Frantz proceeded “from the top down,” delivering an initial “blow of mercy” (coup de grâce) to Renckhart’s neck or heart before proceeding to shatter the limbs of his corpse. If the judges had deemed the crime especially heinous, the procedure went “from the bottom up,” prolonging the agony as long as possible, with Frantz hefting the wagon wheel to deliver thirty or more blows before the condemned murderer expired. Again, Frantz does not remark whether a mercy blow preceded this particular ordeal but it seems unlikely, given the alleged atrocities involved. Finally, the young executioner untied Renckhart’s mangled body and placed it atop a wheel on a pole, which he then hoisted to an upright position so that it might serve as a feast for carrion birds and as a graphic admonition to all new arrivals of the authorities’ deadly seriousness about law enforcement.

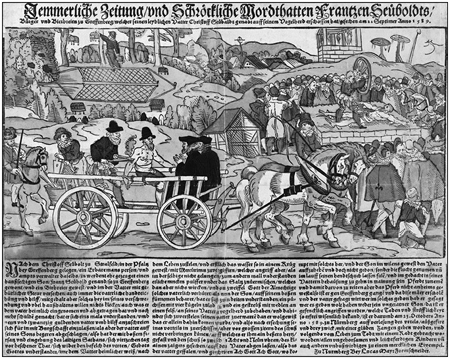

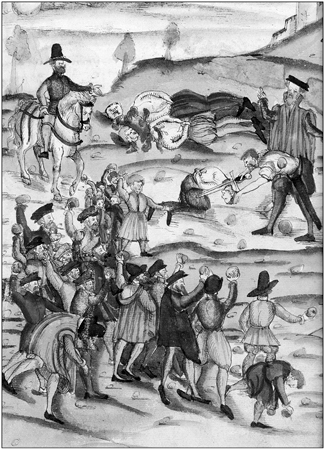

Frantz Schmidt’s 1585 execution of the patricide Frantz Seuboldt, from a popular broadsheet. The upper left portrays Seuboldt’s “inhuman” ambush and murder of his own father while the latter was setting bird traps. In the forefront, Meister Frantz administers the nips with glowing tongs during the procession to the execution grounds. Upon their arrival at the Raven Stone, Seuboldt is staked out and executed with the wheel, his corpse then hoisted atop the wheel and displayed next to the gallows (in background, with heads on stakes nearby).

How did Frantz feel about his role in these macabre blood rituals? His journal entries provide little insight, except perhaps in their very brevity. Was his performance during these journeyman years as tentative as his subsequent recording of it? After all, witnessing such gruesome spectacles was quite another thing from perpetrating them with his own hands. Just as important as attaining the appropriate level of technical expertise, he had to develop the psychological fortitude to look into the eyes of condemned criminals like Renckhart before terminating their earthly existence. Did the young journeyman’s ambition override his innate distaste for his unsavory work, or did he find other ways to make the job more palatable? Above all, how would he keep the near daily violence he administered from consuming him?

The short paragraph that Frantz writes about Renckhart in his journal provides a partial answer. Rather than describe the execution ritual itself, as he often does later in life, the journeyman executioner focuses on Renckhart’s crimes, giving most attention to a recent atrocity that clearly chilled the journeyman executioner to the bone. After briefly mentioning the robber’s other murders, Frantz recounts how one night Renckhart and a companion attacked an isolated rural home known as the Fox Mill. Upon their break-in, Renckhart shot the miller dead [and] forced the miller’s wife and maid to his will and raped them. He then made them fry an egg in fat and lay it on the dead miller’s body [and] forced the miller’s wife to join him in eating. Also kicked the miller’s body and said, “Miller, how do you like this morsel?” The robber’s shocking violations of all human decency in Frantz’s eyes provided all the justification he required in his subsequent administering of death by the wheel. This stratagem of recalling and recording the heinous offenses that had made necessary the very punishments he carried out was a useful discovery that provided continual reassurance to Frantz throughout his long career.

On the road

From the age of nineteen to twenty-four, Frantz continued to use his parents’ home in Bamberg as a base while he traveled the Franconian countryside from one temporary assignment to another. In this respect, his life differed little from the lives of most journeymen his age, all of whom sought to build a reputation and secure a permanent position as a master. Meister Heinrich’s name and professional contacts served him well during this period, providing him entrée into several villages in need of an ad hoc executioner for interrogation or punishment. None of these small communities offered Frantz any hope of a permanent position, but collectively they allowed him to earn his keep while gaining invaluable experience.

His journal entries during these years record twenty-nine executions in thirteen towns, most frequently Hollfeld and Forchheim, each less than a two-day journey from his new home (see map here). He also performed three executions in his father’s stead in Bamberg, one in 1574, the other two in 1577.2 In later years, Frantz would sometimes write long, reflective journal entries in which he speculated on such questions as the motives of the people he executed. But in these early years, only the Renckhart execution runs to more than a terse one or two lines. Instead, professional advancement dominated the young journeyman’s thoughts and writings, and so he concentrates on documenting the number of executions he performed and the variety of killing methods in his repertoire. Even the briefest hint of introspection would have to wait until he was established and secure.

Like many ambitious young men, Frantz evidently knew—perhaps thanks in part to his father’s counsel—that technical proficiency alone would not earn him a coveted permanent position. In the increasingly lucrative, and thus competitive, world of professional executioners, a man also had to cultivate a social network and build a respectable name. Heinrich Schmidt could help his son get in the door, but ultimate success depended on Frantz’s own ability to impress influential legal authorities with both his professional skills and his personal integrity. To that end, building a reputation for honesty, reliability, discretion, and even piety went hand in glove with gaining experience at the gallows. In later years, Frantz would improve his reputation by drawing nearer and nearer to respectable society. At the onset of his career, though, his more urgent need was to push away—to the extent possible—his association with disreputable society. This precocious act of self-fashioning made his journeyman years more difficult and lonely—but it also allowed him to establish many of the habits and character traits for which the later Meister Frantz was known and revered.

In his journeys as a “wander bird,” Frantz encountered individuals from virtually every social rank. We tend to think of premodern Europe as fairly static, but there was in fact considerable geographical mobility. The young executioner was able to identify most travelers immediately by their attire and means of transportation. Fur-bedecked nobles and patricians in silk traveling cloaks were—as they intended—the most conspicuous, journeying by horse or carriage, usually accompanied by at least a few armed retainers. Merchants, bankers, physicians, and lawyers also typically traveled by horse and dressed in crisp woolen mantles. Frantz himself might have had use of his father’s riding horse, but more likely he journeyed as did most other honest folk of modest means, by foot. Along the dirt paths and muddy roads of the Franconian countryside, he would frequently be overtaken and passed by galloping couriers and even plodding transport carts filled with manufactured goods, wine, or foodstuffs. Pilgrims traveling to a religious shrine wrapped themselves in penitential white or sackcloth and moved at a slower gait, while families traveling to a wedding feast or farmers on the way to market hastened along amid boisterous chatter. A young journeyman wearing a modest hat and traveling cloak, perhaps with a walking staff in hand, was one of the most common sights of all.

Rural travel, as Frantz well knew, posed many dangers. Whatever personal encounters he had with highwaymen or other ruffians while under way are lost to history. We do however know of a more insidious threat the young executioner regularly faced and likewise struggled to evade—association with the dishonorable “traveling folk” who also filled the roads.3 The least marginalized of these were the numerous migrant agricultural workers and traveling tradespeople: peddlers, hawkers, tinkers, pewterers, knife grinders, and ragmen. Executioners themselves, like butchers and tanners, were still widely considered part of this group, as were entertainers of all sorts—acrobats, pipers, puppeteers, actors, and bear baiters. If he mingled in public with any of these individuals during his travels, Frantz risked bringing down on his head the very social stigma he sought to escape.

His deep personal familiarity with the criminal underworld, the so-called thieves’ society, put Frantz in an even more uncomfortable spot. Many of his father’s assistants came from unsavory backgrounds, as did of course most of his victims. Like all executioners, Heinrich and Frantz Schmidt were both fluent in Rotwelsch, the colorful street slang of vagrants and criminals that combined elements of Yiddish, Gypsy, and assorted German dialects. A denizen of the underworld, for instance, who had “bought the monkey” (was drunk) might be wary of running into a “lover” (police official), especially if he had recently been “fencing” (begging), “bargaining” (swindling), or “burning” (blackmailing).4 Frantz also knew the signs and symbols that such vagabonds carved or chalked for one another on hospitable houses and inns.5 The extensive personal contact that young Schmidt had with hardened professionals, albeit not in a social context, meant that in most ways he was more a part of their “wised-up” (kocheme) society than the general public’s “witless” (wittische) world. His familiarity with the denizens of both worlds admittedly gave him an advantage in recognizing and steering clear of shady characters, but his years of assisting his father had also taught him that the line between honest and dishonest was neither fixed nor always obvious.

In that respect, the greatest challenge for a young man of the day seeking to establish an upright name came from other young men. Everywhere that Frantz went, he encountered the dominant culture of unmarried males—whether honest journeymen like himself or those engaged in shadowy enterprises—a social world based primarily on drink, women, and sport. Alcohol in particular constituted a key component of male friendship in early modern Germany and held special significance in the rites of passage among young men. Accompanied by raunchy songs and poems, the prolific quaffing of beer or wine could establish the ephemeral bonds of drinking buddies or be part of formal initiation into a local youth group, a military cohort, an occupational association, or even some form of blood brotherhood. Taverns with now quaint names such as the Blue Key or the Golden Hatchet were usually the first stop for all male travelers upon arrival in a village or town, and buying a round of drinks was a particularly effective way for a newcomer to command respect and make new friends, at least at a superficial level.

Like today, young male friendships of the era thrived on competition of all sorts. Card playing and gambling were givens. Wrestling or archery matches provided both a test of physical skill and yet another opportunity for betting. German men indulged to a legendary degree in prolonged drinking bouts and “duels” of wine and beer that occasionally resulted in serious internal injuries or, in rare cases, death. The drunken camaraderie of the taverns often led to much bragging—and exaggeration—about sexual prowess. And of course the dangerous combination of alcohol and testosterone inevitably sparked violence, not just brawls and knife fights among the young men themselves but also attacks on others, especially sexual assaults against women.6

Participation in this rambunctious world was not an option for an ambitious young executioner. His efforts to avoid such company, as well as association with any dishonorable individuals, needed to be relentless and total. The subsequent self-isolation must have been emotionally difficult for Frantz, especially since he had not yet gained the acceptance of honorable society either. Respectable innkeepers remained wary about housing a man of his background, regardless of his commission from the prince-bishop or how finely attired or well-mannered he appeared. On the road, Schmidt could attempt to conceal his profession, even lie about it, or seek lodging elsewhere, in the house or barn of a hospitable stranger. Upon his arrival in the village of execution, though, it became impossible to hide his identity from anyone, so he was effectively shut out of all social gatherings. The only young males willing to share Frantz’s table (and his bar tab) were the very individuals he was trying to avoid—beggars, mercenaries, and probable criminals. His options for female companionship were just as limited: honorable artisans’ daughters wanted nothing to do with him, and consorting with prostitutes or other loose women would undermine the very reputation he was seeking to establish.

Early modern taverns provided young men like Frantz with the opportunity to drink as well as gamble, fight, and pursue sexual exploits. Some moralists considered the taverns “schools of crime,” where thefts and other schemes were often planned, while innkeepers acted as fences and prostitutes known as “thief-whores” picked the pockets of unsuspecting and inebriated customers (c. 1530).

Thus Frantz did not make any great social sacrifice when he came to what was a remarkable decision for a man of his era: never to drink wine, beer, or alcohol of any kind. It was a vow he apparently kept for the rest of his life and for which he eventually became widely known and admired. Frantz’s religious beliefs may have played a role in this choice, but complete abstention from alcohol was rare in the sixteenth century, even among the most godly men and women. Our modern inclination might be to speculate that he had suffered from the embarrassing behavior or drunken violence of someone close to him—perhaps even his own father. But whatever his religious or emotional reasons, Schmidt’s vow not to drink was also a carefully calculated career decision. Early modern Europeans considered it a given that the executioner would drink to excess—a stereotype with a great deal of truth behind it. Compelled to kill and torture their fellow human beings again and again, many in Frantz’s profession sought preexecution courage in a tankard or two of beer or oblivion after the fact in a large quantity of wine. By publicly refuting the legendary fondness of his fellow executioners for the bottle, Frantz found an extraordinary means of underscoring the sobriety, both literal and figurative, of the way he had chosen to live. This jujitsu maneuver cleverly took the disadvantage of his de facto social isolation and turned it into a virtue that distinguished him in the eyes of future employers, and perhaps even society at large. The quiet journeyman who sat without companions—or drink—in a far corner of the tavern may have been lonely, but he knew exactly what he was doing.7

Violence in the pursuit of truth

To obtain a permanent position, Frantz needed, of course, to prove his proficiency in two particular aspects of law enforcement: interrogation and punishment. Both involved a much greater degree of physical violence than most modern legal authorities would consider permissible (at least on the record). It’s reassuring to believe that this contrast is grounded in our own time’s greater sensitivity to human suffering and higher respect for human dignity—but the daily headlines regularly mock any smug sense of superiority on this score. The same unstable alchemy of compassion and retribution that fuels modern debates on criminal justice animated the response to crime in Frantz Schmidt’s time. Why then was early modern criminal justice itself so much more visibly brutal? And why was a compliant instrument of that state violence like Frantz Schmidt so much in demand?

Again, legal authorities of the day, particularly in “progressive” states such as Nuremberg, struggled in vain to span the chasm between their ambition to practice a new, more effective system of criminal prosecution and their continuing reliance on traditional and largely insufficient means to that end. Despite the imperial codifications of the Bambergensis and Carolina, most local authorities’ procedures, personnel, and overall mentality remained grounded in the private accusatorial model of centuries past. In some instances, newly energized criminal courts became tragically susceptible to popular prejudices and personal rivalries, as in the case of the notorious witch panics of the era. More often, secular authorities simply struggled to conceal their profound inability to prevent crime in the first place or to apprehend criminals after the fact. Frantz’s journal is filled with accounts of notorious outlaws who easily evaded authorities, sometimes living out in the open in a foreign jurisdiction, until they were at last brought to court by a victim, a victim’s family member, or a private posse (posse comitatus).8

A cool and reliable executioner typically played the pivotal role in making the most of the few opportunities when a suspected culprit actually landed in official custody. He was the one who began the process by obtaining information from recalcitrant suspects, and he was the one who brought it to a close by orchestrating the ritualized public spectacle of punishment. If at least two impartial witnesses aged twelve or older provided testimony, a suspect usually confessed, and Frantz’s skills in the torture chamber were not required. Material proof—such as stolen items or a bloody murder weapon—could also make the prosecution’s task much easier. Unfortunately, the courts frequently found neither witness nor physical evidence, and the investigation stalled because of the paltry capabilities of pre-nineteenth-century forensic science. Absent any other compelling evidence, conviction of the average suspect thus depended almost exclusively on the accused person’s self-incrimination. At that point, a professional executioner would be summoned. In Bamberg Frantz played the part of the assistant to his father; in those locations he visited on his own, he was in charge.

Like professional interrogators today, Frantz Schmidt and his superiors knew the effectiveness of intimidation and other forms of emotional pressure. One nonviolent but nonetheless psychologically intense method of obtaining a murder confession was the so-called bier test. This ancient Germanic custom, familiar to readers of the Niebelungenlied and other medieval sagas, remained a powerful tool in the professional interrogator’s arsenal. Assembling a room full of witnesses, the executioner and his assistant would force the accused—or even a group of suspects—to approach the victim’s corpse on its stretcher and touch it. If the body bled or gave any other sign of guilt (such as apparent movement), the killer would supposedly be compelled to confess.9

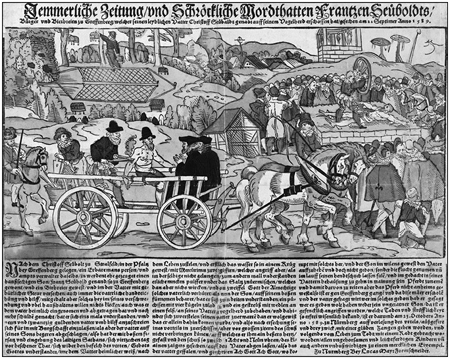

The ancient bier test as practiced by a late medieval court. By the sixteenth century, this last remnant of trial by divine ordeal had lost all official backing, but many people continued to believe that a murder victim’s corpse would bleed or move at the touch of its killer’s hand (1513).

No jurist considered such an event sufficient or even necessarily credible evidence, but the trauma did often succeed in exposing a guilty conscience. Frantz only writes of one application of the bier test during his career, and it happened long after his journeyman days. The accused Dorothea Hoffmennin vehemently denied strangling her own newborn daughter, but when the dead child was brought before her, laying its hand on her skin—which she did with a terrified heart—it received a red bruise on the same spot. Since the young maid kept calm and refused to confess, she was merely whipped out of town with rods. The very fear of undergoing such an ordeal nevertheless provided a vulnerability that the experienced executioner might exploit. Years later, Frantz wrote how another suspected murderer incriminated herself by loudly forbidding her accomplice to reenter the house of the patrician spinster they had just killed in her sleep, fearing that the corpse would “sweat blood” if he approached.10

If initial interviews were unsatisfactory and the consulting jurists found sufficient “indices” to begin torture, Frantz’s superiors ordered him to “strictly bind and threaten” the suspect, the first of five increasingly severe grades of torture.11 The journeyman Schmidt left no record of his interrogation method during these years, but it was likely similar to the well-defined routine he later used in Nuremberg. First he and his assistant would escort the accused from his or her cell to a sealed room with the instruments of torture prominently displayed. In Nuremberg this took place in the “Hole,” or dungeon, in a specially designed torture chamber, which was nicknamed “the chapel” because of its arched ceiling (and perhaps to provide a hint of macabre irony). The small, windowless room of approximately six by fifteen feet stood directly beneath a meeting room in the town hall. In the room above sat two patrician jurors, shielded from the gruesome spectacle below, who consulted their case notes and questioned the suspect through a specially designed air duct linked to the chamber.

Even at this point, the executioner relied more on emotional vulnerability and psychological pressure than on sheer physical coercion. In the “chapel,” Meister Frantz and his assistant would tightly bind the subject—occasionally on the rack, but usually in a chair bolted to the floor—and then painstakingly describe the function of the torture implements on display. One veteran jurist advised inexperienced executioners such as the young Frantz not to be gentle or humble at this point, “but to employ rumor and speculation … saying amazing things [Wunder-Dinge]: that he was a great man who had done great deeds … learned and practiced in his arts, that no person was capable of concealing the truth from his ruses or movements … as he had already happily proven to all the world with the most obstinate villains.”12 Perhaps Frantz even learned from his father a version of “good executioner, bad executioner,” with the two men alternately threatening and consoling a terrified suspect. Most subjects yielded some kind of confession under such conditions, seeking to avoid both the pain and subsequent social stigma of torture.13

For those few other individuals who still resisted, typically hardened robbers, the executioner and his assistant would then begin to apply whatever method of physical coercion their superiors had approved. In Bamberg and Nuremberg the approved options included thumbscrews (usually reserved for female subjects), “Spanish boots” (leg screws), “fire” (candles or torches applied to the subjects’ armpits), “water” (today known as waterboarding), “the ladder” (aka the rack; the subject was strapped to a ladder and either stretched or rolled back and forth on a spiked drum), and “the wreath” (aka “the crown”: a metal and leather band was placed on the forehead and slowly tightened). The most commonly applied torture in Bamberg and Nuremberg was “the stone,” more commonly known as the strappado, in which the subject’s hands were bound behind the back and slowly drawn upwards on a pulley, with stones of varying weight pulling down on the feet. Human ingenuity and sadism inevitably produced countless other stylized forms of inflicting pain—the Pomeranian Cap, the Polish Ram, the English Shirt—as well as crude but effective means of degradation, such as forcing victims to eat worms or feces, or sliding pieces of wood under their fingernails.14 Frantz Schmidt undoubtedly knew of most, if not all, of these methods. But did he or his father—perhaps out of frustration with a particularly recalcitrant suspect—ever resort to such nonsanctioned techniques? Predictably, both his journal and the official records are mute on this point.

The interrogation technique known as the strappado, showing a suspect before one of the stones is attached to his feet (1513).

On rare occasions, Frantz’s instructions prescribed the length of time that duress might be employed, for instance, no more than fifteen minutes for recently delivered mothers. Generally, responsibility for judging the subject’s “torturability” (Foltertauglichkeit) rested entirely with the executioner. Surgeons and physicians did not attend torture sessions until the practice itself was on the verge of being abolished, two centuries later.15 In theory, Frantz’s nonacademic training in human anatomy enabled him to apply sufficient pain without causing serious injury or death. Once he was himself a master, he would be able to call off, postpone, or mitigate torture, though his judgments might occasionally be subject to being overruled. One thieving mercenary who “was already seriously wounded not only on the head but also on both hands and legs” was judged by an older Frantz unlikely to survive a session with the strappado. When the same culprit’s testimony under thumbscrews failed to satisfy the executioner’s superiors, however, Schmidt was ordered to apply more strenuous means, ultimately two torture sessions with fire and four with the wreath. The accused robber’s even more resistant brother-in-law was forced to endure the ladder six times, including frequent torture with wax candles under his left armpit. Not surprisingly, both ultimately confessed and were executed with the sword out of mercy.16

The executioner also bore primary responsibility for keeping all suspects in relatively good health, both before and after interrogation. Frantz knew well the harsh effects of imprisonment, especially on women, and bemoans in his journal when any suspect was forced to endure “the squalor of incarceration” for many weeks in a tiny cell intended for brief holding before interrogation and sentencing.17 He personally tended to the broken bones and open wounds of prisoners and brought in nurses for recently delivered child murderers and other ailing women. This paternal concern for the well-being of imprisoned suspects strikes modern sensibilities as contradictory and even cruel, particularly when the individual was purposely given time to heal so that he or she could be effectively tortured or executed. The irony of the situation was not lost on Frantz and his colleagues. One prison chaplain recounted how a barber-surgeon brought in to assist the executioner “remarked to me during the [condemned’s] treatment that it troubled him he spent so long healing what Meister Frantz would again ruin.”18

Delivering a convicted offender in satisfactory condition for public punishment was never a simple matter, even after Frantz had gained years of experience. A farmer arrested and tortured in 1586 on suspicion of having murdered his stepchild had no sooner confessed to the crime when “God immediately provided a visible sign [of his guilt]” and the suspect fell dead, presumably of a heart attack.19 Torture could also lead to psychological damage, which posed an equal or greater threat of jeopardizing a smooth and effective public execution. After one “hard, stubborn thief” was tortured three times with fire in a single session—and continued to swear to God his innocence—he began to behave “very strangely and unruly” in his cell, alternately weeping uncontrollably and lashing out violently, as well as trying to bite the prison keeper. Until then he had “prayed diligently,” but now he refused to do so or to speak to any person, instead squatting in a corner of the cell and chanting to himself “Dum diddy lump, dear devil come!”20

Young male thieves and robbers, entering the torture chamber with an ample supply of street smarts and bravado, predictably displayed the greatest obstinacy and resilience. Since neither the journal nor the interrogation protocols ever mention comments by the executioner, it’s unclear whether Frantz grew more frustrated during especially long torture sessions with stubborn suspects or with his unrelenting patrician superiors. The truculent sixteen-year-old Hensa Kreuzmayer, accused of arson and attempted murder, was tortured repeatedly over the course of a single day—with the strappado, the wreath, and fire—but in the end, the most he would acknowledge was “uttering a sacramental curse out of anger” at various unfriendly villagers.21 Jörg Mayr, an astonishingly prolific thief of the same age, fought off several similar charges over the course of six weeks before he finally succumbed to despair and literally threw himself on the mercy of the interrogating jurors.22 Older and more seasoned veterans generally recognized the futility of resistance and broke sooner. After one extended but unsuccessful torture session with a veteran highwayman, Frantz’s magisterial superior calmly reassured the suspect that “we will again do with [you] what we want and even have [you] torn to pieces if [you] are not able to confess to having committed a murder,” whereupon the suspect recognized the hopelessness of his situation and confessed in full.23

How did Frantz himself feel about his role as a professional torturer? As the person with the least seniority, the young journeyman was charged with the most brutal parts of the entire ordeal—pulling the rope of the strappado, turning the screws, burning a screaming subject. Most master executioners supervised the procedure but left the actual dirty work to their more dishonorable assistants. Whether Frantz readily passed on these tasks when he himself became a master is unknown—mainly because in nearly half a century of writing, he seldom explicitly acknowledged his own role in the administration of torture. There is no list of torture sessions alongside his tally of executions and corporal punishments, even though private interrogation was a more frequent and longer-lasting activity for him than both of those public performances combined.24 If not for the surviving interrogation transcripts, his participation in these monthly, sometimes weekly, procedures would be completely hidden from view.

Was Frantz ashamed of his unsavory work in the torture chamber or merely reticent about drawing attention to it? The task was in itself no more dishonorable than the public floggings, hangings, or wheel executions that he continued to administer personally until retirement many decades later. Nor, apparently, did he consider such measured violence unjustified. The few times that he writes about torture, Frantz sounds confident that virtually all individuals who made it to this stage, especially the already notorious robbers and thieves, had some degree of culpability. The sole occasion when Frantz expressed regret about the practice came when the mass murderer Bastian Grübel falsely denounced a companion out of enmity and [caused] the man [to be] brought into this town and examined by torture in his presence. [He] did him wrong in this for the murders were not true but lies, thinking that by doing the farmer this injustice the murders would not be discovered and that he would himself be released.25 The executioner’s indignant tone conveys his usual sympathy for all victims as well as an implicit reassurance to himself that unjustified torture remained an anomaly. Otherwise the subject of torture was much more likely to come up in the older Frantz Schmidt’s descriptions of the atrocities committed by marauding robbers during their savage home invasions—an interesting evasion on the executioner’s part.26

Did Frantz really believe the legal axiom of the day that “pain releases truth?” It’s hard to say. He nearly always tried to prompt a confession by using psychological pressure and other nonviolent methods before he resorted to inflicting physical pain. This suggests that he saw torture as a sometimes necessary evil but hardly considered it an indispensable part of the truth-finding process. His repeated expressions of empathy for a suspect’s suffering also make it clear that Frantz Schmidt was no sadist.

Frantz’s assessment of the reliability of physical coercion is harder to gauge. He remarks once in passing that an accused child murderer revealed the truth under torture but this remains an isolated example.27 Throughout the journal he displays an apparent credulity about details produced under torture that would have been virtually impossible for a suspect to remember, but even these, he might have countered, did not affect the ultimate question of guilt.

Did Frantz ever worry that a confession obtained under torture might lead to the execution of an innocent person? It’s impossible to know for sure. Always sensitive to his place in the social hierarchy and the importance of career advancement, an eager young journeyman could console himself that the responsibility for ordering torture lay with his superiors, whom he was bound by oath (and self-interest) to obey and to please. A more experienced and financially secure executioner might find an even greater number of rationalizations to quiet a nagging conscience: if the accused was not guilty of this crime, he was probably guilty of others; speaking up for a possibly innocent suspect wasn’t worth jeopardizing both job and family security; his job was to carry out orders, not decide innocence or guilt.

Above all, Frantz did not consider himself the immovable opponent of a tortured subject, fixated on procuring a damning confession at all costs. His official prerogative to halt or forgo torture gave him considerable discretionary powers in cases where he had doubts about culpability, sometimes resulting in complete dismissal of charges. On at least two occasions later in life, for instance, he successfully recommended the release of older women suspected of witchcraft, on the grounds that they could not withstand the physical strain of even the mildest torture.28 Frantz could also comfort himself with the knowledge that only a tiny minority of the many suspects brought before the council were subjected to torture, that those who were had typically been accused of quite violent crimes, and that even among those who were tortured, only a few suffered more than one session. Finally, he knew that the majority of those tortured would ultimately escape the death penalty, and perhaps one in three would be released with no subsequent punishment whatsoever.29 This crucial semblance of moderation and due process is particularly helpful in understanding how an otherwise empathetic, intelligent, and pious individual might make peace with his role in routinely perpetrating the abominable personal violation that is torture.

Violence in the pursuit of justice

Frantz’s success in carrying out the public spectacle of judicial violence was the sine qua non of his professional reputation. Many premodern criminal punishments appear alternately barbarous or quaint to modern eyes. There seems to be a childlike literalness at work in the way the crime was matched to the punishment, what Jacob Grimm called “a poetry in the law.”30 Some of the essential components—especially collective and public retribution—remained rooted in distant Germanic times, while other ancient influences, notably the lex talionis, or Mosaic law (“an eye for an eye”), gained new life thanks to the evangelical reforms of the previous two generations. The religiously charged atmosphere of the day also added a particular urgency to the legal process, since it was believed that unpunished offenses might bring down divine wrath on an entire community (Landstraffe), in the form of flood, famine, or pestilence. Throughout Frantz Schmidt’s life (and well into the eighteenth century), God the Father’s keen interest in effective criminal law enforcement remained a frequent catalyst to new law-and-order campaigns and even influenced some legal decisions.

Frantz’s ability to effectively administer corporal punishment was a prominent part of his job description. Here the medieval fondness for colorful and “appropriate” public humiliations comes readily to mind: quarreling housewives adorned with “house dragon” masks or “violins” (elongated wooden shackles around the neck and wrists), fornicating young women forced to carry the “stone of shame” (weighing at least thirty pounds), and of course the stocks, where a variety of exposed malefactors endured verbal abuse, spittle, and occasionally thrown objects. Among more established members of the community, by contrast, privately negotiated financial settlements remained the norm.

More violent punishments—such as chopping off the two oath fingers (index and middle) of perjurers and tearing out the tongue for blasphemy—had been relatively common before the sixteenth century. But by Frantz’s time most German authorities deemed such traditions ineffective and potentially disruptive, because they came across as alternately ludicrous or gratuitously cruel. One Nuremberg jurist considered the brutal practice of eye-gouging (for attempted murder) “a harsher punishment than beheading,” and in most parts of the empire it was discontinued by 1600.31 Similarly gruesome mutilations, such as castration and hand-chopping, were also virtually unheard-of by this time.

Despite these trends, Frantz Schmidt was not spared from administering disfiguring corporal punishments. Bamberg and Nuremberg both maintained the punishment of cutting off perjurers’ and recidivists’ fingers and casting them in the river, long after other jurisdictions had abandoned the ancient custom. Over the course of his long career, Frantz would stand on Nuremberg’s Fleisch (Flesh) Bridge to chop off the fingers of nine offenders, including prostitutes and procuresses, false gamblers, poachers, and false witnesses. He would also brand a large N (for Nuremberg) on the cheeks of four pimps and con men, clip the ears off four thief-whores, and snip the tongue-tip off one blaspheming glazier.32

By the late sixteenth century, the traditional punishment of eye-gouging had become rare in German lands (c. 1540).

Between the mid-sixteenth-century decline of legal mutilations and the seventeenth-century rise of workhouses and prisons—in other words, Meister Frantz’s lifetime—the most common corporal punishment in German lands was banishment, often preceded by flogging with rods. Given the dearth of options for addressing lesser crimes, especially minor theft and sexual offenses, Frantz’s superiors in Bamberg and later Nuremberg simply adapted this medieval custom to their needs. Banishment became lifelong (instead of one to ten years), now covered “all the towns and fields” of their respective jurisdictions (instead of just the city proper), and was increasingly underscored by a painful public whipping, or at least time in the stocks. In large German towns, flogging out of town became a regular, at times weekly, event. Between the fall of 1572 and the spring of 1578, Frantz assisted or observed his father’s scourging of twelve to fifteen people a year.33 During his subsequent solo career in Nuremberg, he would himself flog at least 367 individuals, an average of about nine annually, twice that during his peak period of 1579 to 1588. Internal references in the journal indicate that there were still other occasions that Frantz did not include in his tally and many more whippings administered by his assistant.34 Corporal punishment of all kinds was so frequent in Nuremberg that on one occasion all six of the city’s stocks were occupied and Meister Frantz had to bind a recidivist false gambler in the Calvinist Preacher’s chair on the stone bridge (today’s Maxbrücke) and chop off his two oath fingers there, before whipping him out of town once again.35

The ritualistic expulsion of undesirable individuals from a city’s borders had all the essential components that sixteenth-century magistrates loved: strong assertion of their own authority in the beadle’s loud proclamation of the sentence and the churches’ ringing of the “poor sinner’s bells,” the executioner’s humiliating stripping of the culprit to the waist (occasionally women were permitted a cloth for modesty), and the culprit’s painful whipping at the stocks or during the procession to the city’s gate to instill the lesson, as well as an alleged opportunity for the offender to reform, or at the very least to avoid further offenses within their jurisdiction. As in public executions, the danger of mob violence always loomed. In one flogging of “three pretty young women” in Nuremberg, “an enormous crowd ran [after the procession], so that some were crushed under the Ladies’ Gate.”36 Despite the risks, paternalistic rulers found themselves unable to resist the seemingly harmonious blend of retribution and deterrence in these ritualized expulsions—particularly given the absence of viable alternatives.

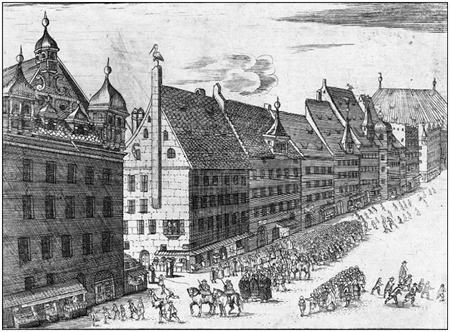

A Nuremberg chronicle portrays Meister Frantz simultaneously whipping four offenders out of town. Note that although the men’s backs are completely exposed, they retain their hats, as does Meister Frantz, who also dons a red cape for the occasion (1616).

The flogging itself was typically administered by the executioner’s assistant or a journeyman executioner, such as young Frantz Schmidt. In Bamberg Heinrich Schmidt chose to perform the task himself, most likely because he was still paid on a fee basis for his work. Out of deference to his father or based on his own work ethic, Frantz would continue to personally perform (and dutifully record) the floggings he administered long after he began earning an annual salary and could have delegated the unpleasant task. He also chose to employ birch rods, which were reputedly more painful than other instruments of flogging and capable of causing permanent injury, or in rare cases death.37 Even so, the executioner himself acknowledged the frequent ineffectiveness of these rituals of pain and humiliation, commenting in his journal on the many culprits he confronts who have already been banished with rods. His jurist colleagues in Nuremberg similarly advised their Augsburg counterparts to use the punishment sparingly with less hardened culprits such as sturdy beggars and other vagrants, else they risked turning them into professional criminals.38

Of course the officially sanctioned violence for which the early modern executioner was most known, and where Frantz’s proficiency needed to be the greatest, was in the public execution itself. One early-twentieth-century German historian considered the criminal justice of this period to be typified by “the cruelest and most thoughtless punishments imaginable,” but in fact a great amount of thought—specifically about the appropriate level of cruelty or ritualized violence—went into every form and instance of punishment.39 As in their modification of traditional corporal punishments, secular authorities in the late sixteenth century also sought an unprecedented and delicate balance of severity and mercy in public executions, all aimed at furthering the rule of law and their own authority in enforcing it. Proceedings that gave off the slightest whiff of mob rule or vigilantism—such as the mass executions of Jews or witches—could no longer be tolerated in “advanced” jurisdictions such as Nuremberg. Medieval traditions that opened the magistracy up to ridicule also needed to be eliminated. These included public trials for criminal corpses as well as for murderous and “abominable” animals (which continued in less enlightened areas well into the eighteenth century).40 A technically proficient and reliable executioner was himself the very embodiment of the sword of justice in action—swift, unwavering, deadly, but never appearing susceptible to arbitrary or gratuitous cruelty.

The new standards that the ambitious Frantz Schmidt had to meet were evident in the transformation of virtually every form of execution in his repertoire. The criminal punishment of women provides an especially vivid example of new adaptations of “simultaneously mild and gruesome” Germanic customs.41 During the Middle Ages and into Frantz Schmidt’s day, most female culprits were punished either by some combination of public humiliation and physical pain or by a financial penalty. Temporary banishment was also a popular option for a variety of offenses. In those few cases where a woman was sentenced to death, by contrast, the punishment could be quite horrendous. Since hanging was considered indecent for women (it allowed spectators to see under their skirts) and beheading was typically reserved for honorable men, the most common form of female execution before the sixteenth century was live burial under the gallows. Long before Frantz Schmidt’s birth, Nuremberg’s leaders declared this punishment “cruel” as well as embarrassingly out of date: “such a death penalty is [still] practiced in few locations within the Holy Empire.” Their decision was also influenced by the messiness of live burial, even if expedited by a stake through the heart. One condemned young woman “struggled so that she ripped off large pieces of skin on her arms, hands and feet,” ultimately leading Nuremberg’s executioner to pardon her and ask magistrates to abolish this form of execution, which they officially did in 1515. Surprisingly, the 1532 Carolina retained the punishment of live burial for infanticide—“to thereby prevent such desperate acts”—but the stipulation was rarely enforced.42

The form of execution most German authorities substituted for condemned women does not appear much of an improvement to modern eyes. Drowning in a hemp sack was also an ancient Germanic punishment, mentioned as early as Tacitus (A.D. 56–117). Many sixteenth-century authorities found the unseen death struggle in the water an appealing alternative to the visible thrashing about in live burial, which often generated a level of sympathy they wished to avoid. Professional executioners such as Frantz Schmidt, however, found the spectacle of forced drowning just as difficult to manage and in some instances even more prolonged. One condemned woman in 1500 survived long enough underwater to free herself from the sack and swim back to the execution platform from which she had been pushed. Her spirited explanation—“[Because] I drank four [liters] of wine ahead of time … the water couldn’t come into me”—failed to impress the attending magistrates, who promptly ordered her buried alive. Shortly before Frantz’s arrival in Nuremberg, his predecessor’s assistant used a long pole to keep the struggling poor sinner from bringing her sack back to the surface, “but the staff broke and an arm came up [out of the water], with much screaming, so that she survived under the water for almost three-quarters of an hour.”43

Frantz himself does not comment on the relative smoothness of his first drowning execution, a young maid from Lehrberg convicted of infanticide in 1578.44 He is unusually forthcoming and even boastful two years later, though, when he and the prison chaplains bring about the abolishment of this form of execution in Nuremberg—a legal precedent gradually imitated throughout the empire. Schmidt’s initial appeal to his superiors was shrewdly practical: the Pegnitz River was simply not deep enough in most spots and, in any event, at the moment (mid-January) “completely frozen over.” Many councilors resisted any change, countering that women should naturally “sink to the bottom out of meekness” and that the young executioner just needed to do a better job of accelerating the process. When Frantz later proposed that three women convicted of infanticide be beheaded, a punishment unprecedented for women, some councilors called the plan too generous and not enough of a deterrent to this “shocking and too frequent crime”—especially given the large crowd likely to attend the imminent joint execution. Fortunately, Frantz’s clerical allies furnished the additional argument that water actually gave power to “the evil spirit,” inadvertently prolonging the ordeal. His jurist backers delivered the coup de grâce, acknowledging that drowning was “a hard death” and undoubtedly deserved, but countered that beheading provided a more effectively shocking deterrent, “since in drowning, one can’t see how the [condemned] person behaves at the end,” while beheading in the open provided a more visible and thus effective “example” to all present. The bridges, which I had had consecrated, were already prepared for all three to be drowned, Frantz writes in his journal, when the magistrates finally relented—with the notable condition that afterward the executioner was to nail all three heads above the great scaffold.45

Even in medieval times, live burial of women was considered a horrendous spectacle, often cut short by a stake through the heart of the struggling victim, as in this illustration of the last such execution in Nuremberg in 1522 (1616).

This compromise solution for the execution of women provided a template for the rest of Frantz’s career, effectively balancing magisterial demands for both “shocking” public examples and smooth, orderly demonstrations of their authority. Nailing heads or limbs of executed culprits to the gallows fulfilled the atavistic bloodlust for retribution and humiliation, while eliminating the public torture aspects of many traditional forms of execution lent the entire procedure a greater legal and even sacred aura. All but two of the poor sinners condemned to be burned at the stake later in Meister Frantz’s career were burned only after beheading or were spared the fire altogether.46 (Burning for witchcraft remained of course pandemic elsewhere in Germany, rarely with strangulation beforehand.) Only one woman was ever again drowned by Frantz—a member of an especially cruel and notorious robber band—and none was ever again buried alive or impaled in Bamberg or Nuremberg (although both practices survived in some Swiss and Bohemian localities for at least another century).47 Instead, the heads of female murderers were often posted on the gallows or poles nearby, as were all four limbs of one traitor, sentenced to be drawn and quartered but executed with the sword here out of mercy.48

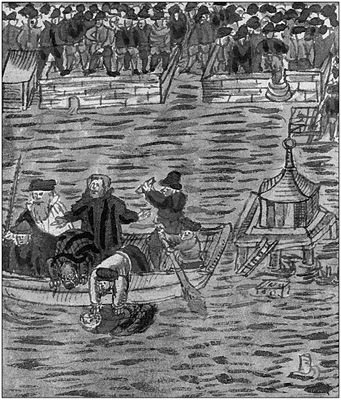

In some jurisdictions, as here in Zurich, the poor sinner was drowned from a boat. In Nuremberg the executioner constructed a temporary scaffolding for this purpose (1586).

There remained only one traditional form of public execution that regularly placed torture at center stage: breaking on the wheel. As in infanticide cases, the deep fears and subsequent outrage unleashed by the crimes of brutal robbers and mercenaries often outweighed the risks to a consistent appearance of governmental calm and moderation. Crowds roared in approval as the vicious robber Niklaus Stüller (aka the Black Banger) was pulled along on a sled at Bamberg, his body torn thrice with red-hot tongs by the journeyman executioner. Together with his companions, the brothers Phila and Görgla von Sunberg, he had murdered eight people, among them two pregnant women from whom they cut out live babies. According to Stüller, when Görgla said they had committed a great sin [and] he wanted to take the infants to a priest to be baptized, [his brother] Phila said he would himself be priest and baptize them, took them by the legs and slammed them to the ground. Stüller’s subsequent death by the wheel at Frantz’s hands seems mild in comparison to the punishment of his companions, later drawn and quartered in Coburg by another executioner.

The ripping of the condemned’s flesh with red-hot tongs and meticulous breaking on the wheel were the most explicitly violent acts Frantz was required to carry out as a professional. Although the number of nips with burning tongs and the number of blows at the wheel were both carefully prescribed in the death sentence, the executioner appears to have enjoyed some leeway, particularly in severity of the blows. At one point later in his career, Frantz’s superiors in Nuremberg actually ordered him “not to go easy on the condemned persons, but rather earnestly seize them with the tongs, so that they experience pain.”49 Yet even in these instances of shocking deeds—such as Hans Dopffer, who murdered his wife, who was very pregnant—the presiding judge and jurors often capitulated to requests for a more merciful and honorable beheading, as long as the bodies were later broken and left to rot on a nearby wheel.50

As with his torture work, Frantz remained mostly silent about the details of his executions with the wheel—seven during his journeyman years and thirty over the course of his entire career. He only once mentions the number of blows administered and otherwise spends the bulk of each entry recounting the multiple grave crimes of the individual in question.51 We know from various accounts, however, that the gruesome ordeal could be quite prolonged and that it evoked genuine terror in captured robbers. Meister Frantz himself describes one traumatized condemned man who had a knife with him [in his cell], stabbed himself twice in the stomach and then threw himself on the knife, but it did not pierce him; also tore his shirt and tried to strangle himself with it, but could not bring it off. Magister Hagendorn, the chaplain, writes in his journal of another murderous bandit who similarly attempted suicide to avoid his fate by “giving himself three cuts in the body with an instrument he had concealed.” Each survived, was nursed back to health by Meister Frantz, and in his time received his prescribed punishment on the Raven Stone.52

Although less violent than the wheel, death by hanging was universally considered just as shameful, in some ways even more so. The indignity of publicly choking to death at the end of a rope or chain was bad enough; the subsequent exposure to ravens and other animals was even more shameful. Many master executioners also delegated this distasteful task to subordinates, but until his retirement four decades later, Frantz Schmidt insisted on carrying out with his own hands the most odious parts of an already disreputable profession. Beginning with his very first execution at the age of nineteen, the journal records his hanging of fourteen men from 1573 to 1578 and 172 individuals over the course of his entire career, mostly adult male thieves, but also two young women and nearly two dozen youths aged eighteen or younger. Frantz was himself taken aback when ordered to hang the two women in 1584—it had never before happened that a woman was hanged in Nuremberg. He appeared even more uncomfortable about the hanging of “unreformable” teenage thieves, but in each instance the diligent professional performed his duty with no reported mishaps.53

The rare hanging of a nobleman, the finance minister of Augsburg, at the same time as what appears to be a youth. The executioner remains on the double ladder until the victims are dead, while the chaplains celebrate below (1579).

Meister Frantz, like most in his profession, would also have disdained hanging as not much of a technical challenge. The executioner’s job at a hanging amounted to not much more than placing a noose around the condemned man’s neck and pushing him off a ladder. In towns without permanent gallows, Frantz was sometimes asked to inspect a temporary structure, but the construction itself was carried out by trained craftsman. As in all executions, it was up to the executioner to keep the condemned person under control during the entire procedure, wherein the greatest difficulty was usually getting the accused to mount the ladder to the noose. Nuremberg chronicles show Meister Frantz and his assistant employing a double ladder for this purpose, sometimes aided by a pulley, a procedure that culminated in the executioner simply shoving the poor sinner off the other ladder “so that the sun shines through between the body and the earth.”54 Some executioners sought to make death especially painful or humiliating for the condemned, hanging them upside down from a chain after strangulation. Nuremberg’s gallows actually maintained a special Jews’ point at one corner for this purpose, but it was never used by Meister Frantz, who instead garroted one Jew in a chair in front of the gallows (as a special favor) and hanged another “in the Christian way.”55

In Frantz’s first three years as a journeyman, all but one of his eleven execution jobs involved the two most dishonorable forms of dispatch, hanging and the wheel. These lowly assignments were an inevitable part of paying his professional dues and building up his credentials in the region. As a result, during the three subsequent years, he was called on to execute nearly as many individuals with the sword (ten) as with the rope (eleven)—a clear indicator of his rising status. Over the course of his long career, in both Bamberg and Nuremberg, these two forms of capital punishment—hanging and beheading—would constitute over 90 percent of his 394 executions.56

The growing preference for decapitation was in fact part of a general trend in German lands over the course of Frantz’s professional life, rooted in both the gradual decline of executions for theft (and thus hangings) and a concurrent rise in mitigation of more extreme forms of final dispatch. During the first half of Schmidt’s career, hanging was nearly twice as common as beheading; by the early seventeenth century, the proportions had reversed.57 Popular recognition of the skill and professional status of the trained executioner rose accordingly.

Frantz’s skill with the sword provided the bedrock of his own professional identity, certainly not his inglorious work as a hangman, a derisive term that he scrupulously avoided. In his own writing, he is always an executioner, a title that emphasizes his close association to the law and courts as opposed to his unsavory work in the torture chamber or with the wheel or rope. The two hangings Frantz decides to date during his journeyman years are singled out only because they were my first execution (1573) and my first execution at Nuremberg (1577). My first execution with the sword (1573), on the other hand, is celebrated as a moment of personal achievement, unparalleled by specific commemoration of any other firsts during his career.58

The sentence the Romans called poena capitas—and professionals like Frantz knew more simply as “capping”—also put the spotlight more fully on the executioner than did hanging.59 Frantz decided first of all whether the poor sinner would kneel, sit, or stand. Standing subjects, who tended to shift around, posed the greatest challenge to the sword-wielding executioner, and Frantz makes careful note of his five successes with this method, all before he reached the age of thirty.60 Once his finesse and reputation were established enough to secure a lifelong employment contract, he reverted to the much more common practice of decapitating a subject who knelt or sat. Sitting bound in a judgment chair became more common over the course of Schmidt’s career, and was especially preferred for women, who supposedly moved around more at the crucial moment. Following a final prayer from the chaplain, the executioner carefully positioned his feet—not unlike a golfer preparing for a perfectly calibrated swing—and trained his eyes on the middle of the subject’s neck. He then raised his blade and struck one graceful blow, typically from behind on the right side, cutting through two cervical vertebrae and completely severing the head from the body. In the words of a common legal formula, “he should chop off his head and with one blow make two pieces of him, so that a wagon wheel might freely pass between head and torso.”61 Following a clean blow, the poor sinner’s head plopped serenely at his or her own feet, while the seated torso continued to splatter the executioner and his assistant with blood from the severed neck. Frantz never mentions any especially prodigious feats with the sword—such as lopping off two heads with one swing, as one of his successors did—but he does ruefully note the few occasions when an additional stroke was required to sever the head completely, a dangerous breech in the dramatic narrative, to which we now turn.

Producing a good death

Public executions, like corporal punishments, were meant to accomplish two goals: first, to shock spectators and, second, to reaffirm divine and temporal authority. A steady and reliable executioner played the pivotal role in achieving this delicate balance through his ritualized and regulated application of violence on the state’s behalf. The court condemnation, the death procession, and the execution itself constituted three acts in a carefully choreographed morality play, what historian Richard van Dülmen called “the theater of horror.”62 Each participant—especially the directing executioner—played an integral role in ensuring the production’s ultimate success. The “good death” Frantz and his colleagues sought was essentially a drama of religious redemption, in which the poor sinner acknowledged and atoned for his or her crimes, voluntarily served as an admonitory example, and in return was granted a swift death and the promise of salvation. It was, in that sense, the last transaction a condemned prisoner would make in this world.

Let us take the example of Hans Vogel from Rasdorf, who burned to death an enemy in a stable [and] was my first execution with the sword in Nuremberg (while still a journeyman) on August 13, 1577. As in all public performances, the preparation behind the scenes was crucially important. Three days before the day of execution, Vogel was moved to a slightly larger death row cell. Had he been seriously wounded or otherwise ill, Frantz and perhaps another medical consultant would have tended to him and perhaps requested delays in the execution date until Vogel regained the stamina required for the final hour. For the most part, though, the executioner focused his attention during this period on ensuring the condition of the Raven Stone or other site, procuring all the necessary supplies, and finalizing the logistics of the trial and procession to execution.

While awaiting judgment day, Vogel might receive family members and other visitors in the prison or—if he was literate—seek consolation by reading a book or writing farewell letters. He might even reconcile with some of his victims and their relatives, as did a murderer who accepted some oranges and gingerbread from his victim’s widow “as a sign that she had forgiven him from the depths of her heart.”63 The most frequent visitors to Vogel’s cell during this period would be the prison chaplains. In Nuremberg the two chaplains worked in concert and sometimes in competition, attempting to “soften his heart” with appeals combining elements of fear, sorrow, and hope. If Vogel couldn’t read, the clerics would have shown him an illustrated Bible and attempted to teach him the Lord’s Prayer as well as the basics of the Lutheran catechism; if he was better schooled, they might engage him in discussions about grace and salvation. Above all, the chaplains—sometimes joined by the jailer or members of his family—would offer consolation to the poor sinner, singing hymns together and speaking reassuring words, while repeatedly admonishing the stubborn and hard-hearted.

Obviously, a submissive prisoner made for a smoother execution, but the visiting clerics had nobler motives. Dying “in the faith” was of special concern to Frantz’s Nuremberg colleague Magister Hagendorn, and in addition to preparing a prisoner to go to the execution site with calm resignation, he hoped to instill in the condemned some degree of piety and understanding. His own journal entries reveal a particular tenderness toward young women convicted of infanticide. He is initially troubled that Margaretha Lindtnerin, condemned in 1615, has learned so little of her catechism, despite over seven weeks of confinement. In the end, however, she obligingly displays all the hallmarks of a good death:

She was very perseverant in her Cross, prayed fervently, and every time that her baby or parents were mentioned, she began to weep bitter tears; had quite resigned herself to her imminent death, strolled out very calmly, enthusiastically blessed those known to her while under way (since she had served here eight whole years at different places and was fairly well-known) and fervently prayed with us. When we came with her to the execution site, she started and said, “Oh God, stand by me and help me get through it.” Afterward she repeated it to me, blessed the crowd and asked their forgiveness, [then] she stood there, as if stunned and could not talk until I spoke to her twice or thrice, then she began to talk, again blessed the crowd and asked their forgiveness, [then] commended her soul to the hands of the Almighty, sat down in the chair, and properly presented her neck to the executioner. Since she persevered in the right and true faith until her end, she will also [attain] the end of her faith, which [according to] 1 Peter chapter 1 is the salvation and blessing of souls.64

Whatever their success in effecting an internal conversion, the clerics were at minimum expected to sufficiently calm the condemned Vogel for the final component of his preparatory period, the famed “hangman’s meal.” Ironically, Frantz was not directly involved in this ancient custom (possibly because of its disreputable name), and allowed the prison warden and his wife to oversee its implementation in a special cell with table, chairs, and windows, known in Nuremberg as “the poor sinner’s parlor.” As in those modern countries that still maintain capital punishment, Vogel could request whatever he wanted for his last meal, including copious quantities of wine. The chaplain Hagendorn attended some of these repasts and was frequently appalled by the boorish and ungodly behavior he witnessed. One surly robber spat out the warden’s wine and demanded warm beer, while another large thief “thought more of the food for his belly than his soul … devouring in one hour a large loaf, and in addition two smaller ones, besides other food,” in the end consuming so much that his body allegedly “burst asunder in the middle,” as it swung from the gallows.65 Some poor sinners, by contrast (especially distraught young killers of newborns), were unable to eat anything whatsoever.

Once Vogel was adequately satiated (and inebriated), the executioner’s assistants helped him put on the white linen execution gown and summoned Frantz, who from this point on oversaw the public spectacle about to unfold. His arrival at the cell was announced by the warden with the customary words, “The executioner is at hand,” whereupon Frantz knocked on the door and entered the parlor in his finest attire. After asking the prisoner for forgiveness, he then sipped the traditional Saint John’s drink of peace with Vogel, and engaged in a brief conversation to determine whether he was ready to proceed to the waiting judge and jury.

A few poor sinners were at this point actually jubilant and even giddy about their imminent release from the mortal world, whether out of religious conviction, exasperation, or sheer intoxication. Sometimes Frantz decided that a small concession might be enough to ensure compliance, such as allowing one condemned woman to wear her favorite straw hat to the gallows, or a poacher to wear the wreath sent to him in prison by his sister. He might also ask an assistant to provide more alcohol, sometimes mixed with a sedative he prepared, although this tactic could backfire, leading some women to pass out and making some of the younger men still more aggressive. The highwayman Thomas Ullmann almost beat Frantz’s Nuremberg successor to death at this juncture until subdued by the jailer and several guards. Once confident that Vogel was sufficiently calmed, Frantz and his assistants bound the prisoner’s hands with rope (or taffeta cords for women) and proceeded to the first act of the execution drama.66

The “blood court,” presided over by a patrician judge and jury, was a forum for sentencing, not for deciding guilt or punishment. Vogel’s own confession, in this case obtained without torture, had already determined his fate. During the Middle Ages, this judicial pronouncement had been the central moment of the condemnation process, usually taking place in the town square. By the sixteenth century, the subsequent execution now enjoyed this elevated status, with the “court day” itself taking place in a special chamber in the town hall, closed to the public. As in the subsequent procession and execution, the overarching goal of this preliminary stage was to underscore the legitimacy of the proceeding, but in this instance the audience being reassured comprised the executing authorities themselves.

The brisk procedure was accordingly ritualistic, hierarchical, and formal. At the end of Nuremberg’s chamber, the judge sat on a raised cushion, holding a white rod in his right hand and in his left a short sword with two gauntlets hanging from the hilt. Six patrician jurors in ornately carved chairs flanked him on either side, like him wearing the customary red and black robes of the blood court. While the executioner and his assistants held the prisoner steady, the scribe read the final confession and its tally of offenses, concluding with the formulaic condemnation “Which being against the laws of the Holy Roman Empire, my Lords have decreed and given sentence that he shall be condemned from life to death by [rope/sword/fire/water/the wheel].” Starting with the youngest juror, the judge then serially polled all twelve of his colleagues for their consent, to which each gave the standard reply, “What is legal and just pleases me.”

Before confirming the sentence, the judge addressed Vogel directly for the first time, inviting a statement to the court. The submissive poor sinner was not expected to present any sort of defense, but rather to thank the jurors and judge for their just decision and absolve them of any guilt in the violent death they had just endorsed. Those relieved souls whose punishments had been commuted to beheading were often effusive in their gratitude. A few reckless rogues were so bold as to curse the assembled court. Many more terrified prisoners simply stood speechless. Turning to Frantz, the judge then gave the servant of the court his commission: “Executioner, I command you in the name of the Holy Roman Empire, that you carry [the poor sinner] to the place of execution and carry out the aforesaid punishment,” whereupon he ceremoniously snapped his white staff of judgment in two and returned the prisoner to the executioner’s custody.67

The second act of the unfolding drama, the procession to the site of execution, brought the assembled crowd of hundreds or thousands of spectators into the mix. Typically, the execution itself had been publicized by broadsheets and other official proclamations, including the hanging of a bloodred cloth from the town hall parapet. Vogel, his hands still bound in front of him, was expected to walk the mile or so to the gallows. Sometimes, if the condemned suffered from physical exhaustion or an infirmity, Frantz’s assistants transported the poor sinner on an elevated chair. This was often the case with the elderly and disabled women such as the swindler Elisabeth Aurholtin, who had only one leg.68 Violent male criminals and those sentenced to torture with hot tongs were bound more firmly and placed in a waiting tumbrel or sled, pulled by a workhorse used by local sanitation workers, known in Nuremberg as a Pappenheimer. Led by two mounted archers and the ornately robed judge, also usually on horseback, Frantz and his assistants worked hard to keep up a steady forward pace while several guards held back the teeming crowd. One or both chaplains walked the entire way one on either side of the condemned, reading from scripture and praying aloud. The religious aura of the entire procession was more than a veneer, and in Frantz’s career only the unconverted Mosche Judt was “led to the gallows without any priests to accompany or console him.”69

During this phase, the executioner’s customary obligation to respect the last wishes of the condemned as well as to avoid alienating the crowd often required considerable restraint on Frantz’s part. Hans Vogel apparently offered little resistance, but the thief and gambling cheat Hans Meller (aka Cavalier Johnny) said to the jurors as he left the court, “God guard you; for in dealing thus with me you will have to see a black devil one day,” and as he was led out to the execution displayed all kinds of arrogance. Still, the executioner waited patiently while Meller sang not one but two popular death songs at the gallows: “When My Hour Is at Hand” and “Let What God Wills Always Happen.” The thieves Utz Mayer (aka the Tricky Tanner) and Georg Sümler (aka Gabby) were similarly fresh and insolent when being led out, howling, but also permitted to sing “A Cherry Tree Acorn” before the nooses were put around their necks.70

An execution procession in the inner city of Nuremberg. Here two guards on horseback lead the poor sinner on foot, with a chaplain on either side of him (c. 1630).