5

THE HEALER

This policy and reverence of age makes the world bitter to the best of our times; keeps our fortunes from us till our oldness cannot relish them. I begin to find an idle and fond bondage in the oppression of aged tyranny; who sways, not as it hath power, but as it is suffered.

—William Shakespeare, King Lear, act 1, scene 2, 46–51 (1606)

The word virtue, I think, presupposes difficulty and struggle, and something that cannot be practiced without an adversary. This is perhaps why we call God good, mighty, liberal, and just, but do not call Him virtuous.

—Michel de Montaigne, “On Cruelty” (1580)1

Over nearly a half century as an executioner, Meister Frantz Schmidt confronted a bewildering array of human vice and cruelty. Yet in all that time, no culprits provoked a more primal revulsion in Meister Frantz than the sociopathic highwayman Georg Hörnlein of Bruck and his equally depraved henchman Jobst Knau of Bamberg. The executioner’s meticulous recounting of their myriad offenses—a mere sampling by his own acknowledgment—constitutes the single longest entry in his journal. In the company of other unsavory associates, most frequently Georg Mayer (aka Brains) from Gostenhof, Hörnlein and Knau roamed the back roads and forests of Franconia for years, assaulting, robbing, and brutally murdering scores of peddlers, wandering journeymen, farmers, and other travelers, including women and youths. After itemizing more than a dozen known examples of their perfidy, Meister Frantz prepares to end the day’s entry. But then—we can almost see him shake his head in exasperation—he changes his mind and goes on to record still more damning examples of the duo’s infamy, including that they attacked people on the Mögeldorfer meadow and everywhere that citizens went for walks … as well as attacked eight people on the streets of Heroldsberg, severely wounding a man and a woman and chopping the hand of a carter in two.

His disgust almost palpable, Schmidt continues with a blow-by-blow account of what he obviously considers to be the most disturbing incidents of the robbers’ long rampage:

Six weeks ago [Hörnlein] and Knau, together with their companions, were consorting with a common whore, when she gave birth to a son in [Hörnlein’s] house, whereupon Knau baptized it, then cut off its little right hand while alive. Afterward his companion, called Blacky, who acted as godfather, tossed the baby in the air, so that it fell upon the table, and said, “So big must my little godchild grow!” Also exclaimed, “See how the devil runs his trap!” then cut its throat and buried it in his little garden. Over eight days later, when Knau’s whore bore a baby boy, Knau wrung its little neck, then Hörnlein cut off its little right hand and later buried it in his shed.

The sheer horror of both moments comes through in Schmidt’s writing, as he contrasts the diminutive terms baby, little neck, and little right hand with the drunken men’s cold-blooded mockery of baptism and godfatherly affection. For Frantz, the incident epitomizes the pair’s utter depravity, and he recalls with undisguised satisfaction the two burning nips that each man received on his arms and legs before suffering a painful execution on the wheel “from the bottom up” on January 2, 1588. Nine days later he executed their accomplice Brains, also with the wheel, and a week after that, he dispatched Hörnlein’s wife and accomplice, Margaretha, employing the supposedly abolished death with water, revived one final time by the council—without protest from the executioner—for this especially heinous offense.2

But why were these men chopping off babies’ hands in the first place? It was not a random atrocity. During Knau’s interrogation, which involved repeated applications of the strappado under the supervision of Meister Frantz, the robber claimed that the right hand of a newborn male was widely known to bring good luck, even invisibility, a useful asset for a professional thief. He said that Hörnlein told him he had cut off many babies’ hands during his travels and successfully used the “little fingers” as candles during break-ins, “so that no one awoke.” (In England this practice was known as the Hand of Glory.)3 Hörnlein confirmed this account in his own confession under torture, elaborating that the hands must stay buried for eight days, preferably in a stable, after which they may be dug up and carried. He admitted instructing Knau in this practice and giving him one of the hands for his own use, but professed only a modest expertise in any other of the “magical arts.” When pressed further, however, Hörnlein conceded that one old woman taught him how to carry a small sack of lead and gunpowder to three successive Sunday masses and thereby gain magical power. He also acknowledged stealing a piece of rope “in broad daylight” from the gallows at a nearby town and carrying it around with his other talismans as protection against gunshot. Challenged by skeptical interrogators, Hörnlein retorted that he even got his two companions to shoot at each other as a test of the charm’s power, and since neither was harmed, he won five gulden from each of them.4

Magical spells and curses were ubiquitous in Meister Frantz’s world. His contemporaries energetically disputed the nature and efficacy of such powers (not to mention their source). But virtually no one challenged the essential mysteriousness of the natural world—and thus the possibility that with certain occult knowledge, human beings might be able to wield some sort of magical power. This fluid and often contradictory quality of pre-eighteenth-century popular beliefs about magic presented Meister Frantz with a predicament. In his sideline as a man of medicine, Schmidt could benefit by exploiting ancient magical beliefs about the “healing power” of the executioner and his equipment. And yet with the European witch craze at its height, a practitioner who bore even a tenuous link to magic faced undeniable danger as well. At once feared and respected—not unlike a powerful wise man or tribal shaman—Frantz was sought out (and well paid) for his healing expertise. But he also risked accusations of incompetence or dark magic from dissatisfied patients or any of his numerous and diverse competitors in a ruthless medical marketplace.

This ambiguous and vulnerable position was of course nothing new to Nuremberg’s executioner. Just as he turned governmental demand for pious and responsible state killers to his personal advantage, Meister Frantz also exploited the healing aura surrounding his craft to further advance his quest for respectability—all the while artfully avoiding the wrath of zealous “witch finders” and jealous medical rivals alike. But medicine—as he revealed later in life—had always represented much more to the longtime executioner than a means to an end or a reliable source of supplemental income. Unlike the odious profession foisted upon him, the doctoring art was his true vocation. Almost every person, Frantz writes, has an enduring inclination toward a certain thing by which he might earn his keep, and for him, Nature [herself] had implanted in me the desire to heal.5 More than his role in the redemptive ritual of the execution, his lifelong work in physical healing provided the executioner with a sense of accomplishment, purpose, even restoration. His struggle to secure this professional identity for himself and his sons would in fact shape the final three decades of his life. Whether Meister Frantz’s own painstakingly constructed and formidable reputation as an executioner would aid or hinder that final self-fashioning remained to be seen.

Live bodies

All premodern executioners were presumed to possess a certain amount of medical expertise. Some were even appointed to their posts explicitly because of their reputed skills in healing people or animals, typically cows and horses. Nuremberg’s magistrates rehired one of Frantz’s notoriously dissolute predecessors less than a year after angrily dismissing him expressly “because his doctoring greatly helped many injured and sick people to recover, and since Jörg Unger, the current executioner, is absolutely worthless [in that respect].”6 In the day of Frantz Schmidt’s father, medical consulting had constituted a minor supplement to the salary of most executioners. By the time Frantz himself became professionally active, fees for healing might constitute as much as half of an executioner’s annual income.7 Following his official retirement in 1618, Schmidt would become almost completely reliant on earnings from his medical work, which continued to flourish until his death, several years later.

The varied and sometimes shadowy array of medical and quasi-medical services available in the premodern world represented market competition at its unregulated finest. Academically trained physicians boasted the highest level of official certification, but their small numbers and high fees made them inaccessible to the majority of the population. Guild-trained barber-surgeons, “wound doctors,” and apothecaries enjoyed a similar aura of respectability and were at least ten times more prevalent than academic physicians in large cities such as Nuremberg.8 Typically, these professionals trained as apprentices and journeymen several years longer than physicians studied at university. By the late sixteenth century, virtually every German state employed its own official physicians and barber-surgeons as well as apothecaries and midwives, imbuing each profession with still greater legitimacy and credibility.

Of course, institutional endorsements of this nature did not prevent most people from turning to any of a variety of nonsanctioned “empirics”—peddlers, traveling apothecaries, oculists, Gypsies, and religious healers—each hawking an assortment of curative powders, compounds, ointments, and herbs. Physicians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries routinely derided the healing abilities of such “quacks” and “charlatans,” but at least some of these roving practitioners offered remedies that actually provided relief in certain cases. Sulfur salves did occasionally clear up skin conditions, and certain herbal concoctions did manage to soothe some aching backs. Obviously, the more sweeping and outlandish claims of itinerant healers were sheer hokum. But at least these traveling quacks advertised their wares with humorous songs, diverting theatrics, and even the occasional snake-handling show (to promote a tonic that provided immunity from any bites).

The healing reputation of Meister Frantz lacked any official backing or carnivalesque promotions, but it unquestionably benefited from the many folk beliefs surrounding his nefarious profession. Like the “cunning” men and women found in practically every village, executioners allegedly knew secret recipes and cures for a variety of ailments—ranging from cancer and kidney failure to toothaches and insomnia—information typically passed down orally to their young acolytes. The controversial physician Paracelsus (1493–1541), who publicly rejected most of what he’d been taught in medical school, famously claimed that he learned the bulk of his healing remedies and techniques from executioners and cunning people. The Hamburg executioner Meister Valentin Matz was widely reputed “to know herbs and sympathy [healing] better than many learned doctors.”9 Whatever the efficacy of an executioner’s treatments, the “sinister charisma” of Frantz and his fellow practitioners gave them an invaluable advantage in the highly competitive (and highly lucrative) medical marketplace of the day. Sons of executioners frequently profited from the association as well, and were able to operate prosperous medical practices even if they did not follow their fathers into the execution profession. Many widows and wives of executioners also did medical work, sometimes competing for patients with local midwives.10

But how much did Meister Frantz truly know about the art of healing, and where did he learn it? Meister Heinrich certainly would have taught his son all that he could. But, having grown up as the son of an honorable tailor, Heinrich would have had to learn the healing arts on the job, as it were. Once the Schmidts had been accepted into the profession, other executioners probably shared some of their secrets, knowing that direct competition from a geographically distant colleague was unlikely. The many criminals and vagrants Heinrich and Frantz encountered during their work provided another fecund source of information, often including magical incantations, but this type of healing ventured into risky territory.

The most valuable resources for a literate executioner were probably the numerous medical pamphlets and other reference works that flooded the print marketplace from the early sixteenth century on.11 University-trained physicians just a few generations later would have been scandalized by the do-it-yourself approach of most popular medical manuals in Frantz Schmidt’s day. More shocking still, in many instances the popularizers were themselves members of the medical elite. The respected physician Johann Weyer (1515–88), today famous as an early vocal opponent of the witch craze, was better known to fellow healers of his era for his Doctoring Book: On Assorted Previously Unknown and Undescribed Illnesses, which covered treatment for conditions ranging from typhus and syphilis (hardly “unknown” in 1583) to “night attacks” and diarrhea.12 Weyer assumed his readers had little or no professional training and describes symptoms and cures in clear, specific, and jargon-free language, supplemented by illustrations of the relevant herbs, medicinal insects, and toads. He also sprinkles biblical references throughout the text, as did most popular authors of the era, beginning with an opening reminder that suffering and illness themselves were the result of Adam and Eve’s original fall from grace.

Hans von Gersdorff’s Fieldbook of Wound-Healing, reprinted several times after its initial 1517 publication, was an even more likely resource for Meister Frantz.13 Based on the author’s extensive experience as a military wound doctor, the 224-page compendium is practically a medical education in itself, beginning with a discussion of the respective roles in health of the four humors, the elements, and the planets, and then offering a step-by-step guide to diagnosing symptoms and applying treatments. Though Gersdorff focused more on external wounds, he also described basic human anatomy, and included several carefully marked illustrations. Like Weyer and other popular authors, he provided illustrations of herbs as well as schematics that show the reader how to construct scalpels, cranial drills, braces for broken limbs, clamps, and even a still. Just as crucially for any nonacademically trained healer, the Fieldbook included an extensive glossary of Latin medical terms and their German translations, as well as a thorough alphabetical index of symptoms, body parts, and treatments.

In accounting for Meister Frantz’s medical success, we should not underestimate the sheer value of listening to patients.14 A reassuring air of self-confidence and other interpersonal skills could go a long way, particularly since conversation constituted a much more important component of the early modern medical consultation than did physical examination. In the words of one popular manual, “A good case history is already half of the diagnosis.”15 Learning about a patient’s occupation, family members, diet, sleeping habits, and more would be useful for any practitioner, but especially for executioners and other folk healers, who could draw on neither the official certification of physicians and barber-surgeons nor the entertaining showmanship of traveling empirics. Meister Frantz could succeed only by painstakingly building up a broad base of loyal patients who felt that he understood them and their ailments. The famed “executioner’s touch” may have gotten some patients through the door, but given the abundance of healing alternatives available, it would not have kept them coming back had not some successful healing actually occurred.

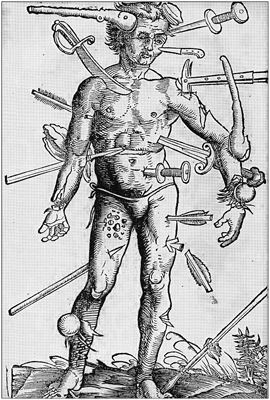

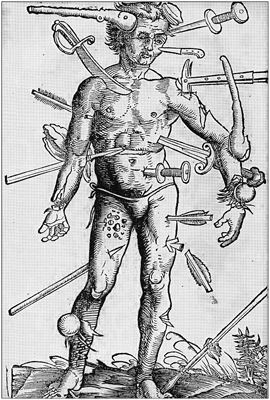

The much-reprinted “wound man” illustration from Hans von Gersdorff’s Fieldbook, indicating the variety of human-inflicted injuries that executioners and barber-surgeons regularly treated (1517).

Genuine skill was especially essential in the executioner’s traditional sphere of medical activity, namely “external treatments” such as resetting broken bones, treating severe burns, cauterizing the bleeding from amputated limbs, and healing open sores or gunshot wounds. More than a third of the wounds treated by wound doctors and executioners resulted from attacks with knives, swords, or guns.16 These were areas of demonstrable expertise for Frantz, since his years of work in the torture chamber gave him extensive experience in how to avoid severely wounding subjects during interrogation as well as how to heal them before questioning or public execution. Frantz apparently received no supplemental fee for his work healing prisoners, but some of his fellow executioners earned three or four times as much for healing a criminal suspect as they did for the torture they had just administered.17

Schmidt’s medical ledgers have not survived. But by his own estimate, in nearly fifty years of medical practice he treated more than fifteen thousand patients in Nuremberg and its surrounding territories.18 Even accounting for some hyperbole as well as the occasional double-counting (Frantz was never good with numbers), this is a remarkable figure. It means that Meister Frantz saw on average more than three hundred patients a year—at least ten times as many individuals as he tortured or punished. Did this knowledge offer him consolation for the agonies that he intentionally inflicted? Did these nearly daily medical experiences reinforce his already deep compassion for the suffering of crime victims? Undoubtedly his widespread reputation as a successful healer helped mitigate the disdain normally reserved for executioners. But it was not enough in itself to make him or his family honorable.

In this context, the selective way that people of the era interpreted the effect of the executioner’s touch appears especially mystifying and capriciously cruel to modern sensibilities. The very individuals who refused to share a table or drink with the publicly reviled executioner, much less allow him into their homes, apparently had no qualms about visiting Frantz in the Hangman’s House and allowing him to lay hands on them there.19 The privacy of such encounters in part accounts for the double standard, but there was apparently no secrecy or shame involved in consulting Meister Frantz for medical reasons. Admittedly, given the nature of his healing expertise, the majority of his patients were soldiers, manual laborers, and farmers. Respectable artisans, however, also consulted him on a regular basis, as did patricians and even some nobles, among them three imperial emissaries, the cathedral provost of Bamberg, and a Teutonic knight, as well as several patrician city councilors and their family members.20 The steady flow of individuals from all ranks of society into the Hangman’s House clearly gives the lie to any absolute marginalization of the executioner and his family. On the other hand, this regular contact with people who shunned them in public must have made the Schmidts’ unique limbo-like social status even more difficult to bear.

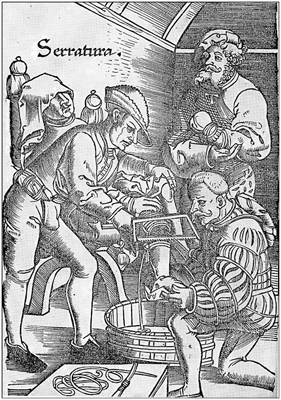

A wound doctor performs an amputation on an inebriated but still conscious patient. Wound doctors and barber-surgeons constituted Frantz’s main competition in the medical marketplace (c. 1550).

Treating external wounds was also the provenance of barber-surgeons, and this predictably led to frequent disputes between them and executioners, conflicts that usually resulted in governmental intervention. Here too, Frantz’s success at building both his personal and professional reputations appears to have staved off the wrath of competitors and the city council alike. He was never once censored by his superiors on this score, and in 1601 they actually referred one man, who complained about a local barber’s unsatisfactory healing of his seven-year-old son’s right knee, not to the municipal physicians but to Meister Frantz.21 Eight years later, the barber Hans Duebelius claimed that because Meister Frantz had previously treated an injured innkeeper, the barber guild would consider him dishonorable if he attempted to cure the same man. Councilors reassured Duebelius that he could proceed without fear of contamination, but they also declined to reprimand the executioner for his own medical activity.22 It’s unlikely that Nuremberg’s barber-surgeons embraced Frantz as a fellow professional, but neither did they openly challenge either his skills or his obvious clout with the magistracy.

Another potential threat to Frantz’s medical success was the rapid ascendancy during his lifetime of the academically trained physician. These professional healers had long occupied the top rung in terms of both prestige and income, but their numbers remained small. Nevertheless, from the late sixteenth century on, they began to assert a new dominance in the medical marketplace. First, they consolidated in German cities, forming quasi-governmental bodies, such as Nuremberg’s Collegium Medicum, established in 1592 under the leadership of Dr. Joachim Camerarius. At the same time, physicians convinced secular authorities that the diverse and often “ignorant” methods of “practical healers”—even including guild-certified barbers, apothecaries, and midwives—required closer regulation and supervision. In Nuremberg this meant more restrictions for licensed practitioners and large fines, possibly even banishment, for amateur “tooth breakers,” alchemists, wise women, Jews, black magicians, and other empirics.23

Fortunately for Frantz Schmidt and his successors, the Collegium Medicum did not assume oversight of their medical activity, but it did restrict them to treating external injuries, “about which they have some knowledge.”24 Meister Frantz also appears to have successfully avoided the open conflicts with physicians that were common among fellow executioners throughout the empire, including his immediate successors.25 Surprisingly, Frantz’s forensic work brought him into more direct and regular contact with these patrician professionals than with the artisanal barber-surgeons, who were much closer to him in training and expertise. Perhaps the respect Schmidt apparently enjoyed in official circles even encouraged him to daydream about one of his sons pursuing this noble—and as yet unreachable—profession. The day when such a social leap would be possible was closer than he imagined.

Dead bodies

Although much of Meister Frantz’s work required him to engage with the living—prisoners, officials, patients, and the like—he also spent a significant amount of time with the dead or, to be more specific, with the cadavers of the poor sinners he had executed. Some of the bodies of those he dispatched received the same treatment as those of any other departed souls, including burial on consecrated ground.26 The majority, however, met a less happy fate. The corpses of hanged thieves and murderers broken on the wheel of course remained exposed to the elements, their crumbled remains eventually swept into a pit under the gallows. Other cadavers were handed over to the executioner for dissection or other use. In no instance was the body of an executed criminal allowed to go to waste; it functioned instead as evidence of the court’s mercy, a gruesome warning, or a useful medical object.

In premodern Europe it was commonly believed—by academic physicians and folk healers alike—that the bodies of the dead possessed tremendous curative powers. This led to a practice that strikes the modern sensibility as bizarre, even disturbing, but that enjoyed widespread acceptance in the era of Meister Frantz: namely the ingestion, wearing, or other medical use of human body parts to heal the sick or injured. Belief in the curative power of various types of human remains can be traced back at least to the time of Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23–79) and would continue to thrive into the eighteenth century.27 Despite this tradition’s obvious affinity with magic, virtually all medical professionals of the day insisted that the practice had a firm foundation in natural philosophy and human anatomy itself. According to followers of Paracelsus, also known as chemical doctors, human skin, blood, and bones possessed the same healing powers as certain minerals and plants and transferred a curative spiritual force to the ill person. Classically trained Galenist physicians scoffed at such “magical” explanations, and instead insisted that body parts healed the sick by restoring the internal balance of the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile). Virtually no healer, formally trained or not, disputed the received wisdom that a recently deceased human body provided a panoply of curative supplies.

Drinking blood, “the noblest of the humors,” was considered an especially potent remedy with many uses, among them dissolving blood clots, protecting a patient from painful spleen or coughing, preventing seizures, opening up blocked menstruation, or even curing flatulence.28 Since the medical establishment believed blood to be continuously concocted by the liver, its supply was also theoretically unlimited, thus diminishing any concern over frequent bloodletting, or phlebotomy, intended to restore the humoral balance. Because age and virility determined the potency of the fluid, the blood of suddenly executed young criminals, whose life force had not yet had a chance to escape, was especially prized. Epileptics, eager to drink the warm and fresh poor sinner’s blood, frequently lined up next to the scaffold following a beheading—an alarming scene for us to envision, yet an unremarkable one for Frantz Schmidt and his contemporaries.

Before the mid-seventeenth century, Meister Frantz and his fellow executioners enjoyed a near monopoly on the various human body parts used for popular healing. Many of them ran side businesses supplying apothecaries and other eager customers. The official pharmacopoeia of Nuremberg, stocked largely by the cadavers of executed criminals, included whole and prepared skulls, “human grains” (from ground bones), “marinated human flesh,” human fat, salt from human grains, and spirit of human bone (a potion derived from boiling bones). Pregnant women and people suffering from swollen joints or cramps wore specially treated strips of human skin, known as human leather or poor sinners’ fat. The healing power of mummy, as preserved human flesh was generically known, even became the focus of a new devotional mysticism devised by the Jesuit Bernard Caesius (1599–1630). There is no way to know how much additional revenue Frantz earned from the human parts trade or to what degree he even engaged in this to-our-eyes ghoulish but lucrative practice.29

Inevitably, some healers of the era also promoted various explicitly magical uses for human body parts. One fellow executioner’s recipe for treating a bewitched horse called for a powder made out of certain herbs, cow fat, vinegar, and burnt human flesh—all mixed with a shaved stick found on a river’s bank before sundown.30 Academically trained Protestant physicians, eager to debunk Catholic belief in the power of saints’ relics, vociferously denied that human body parts had any such supernatural power. They accordingly dismissed as superstition such uncomfortably akin beliefs as the popular claim that the finger or hand of an executed thief would bring good luck in gambling or, if consumed by a cow, provide protection against witchcraft. Catholic authorities in Bavaria similarly professed shock “that many people dare to take things from executed criminals, and seize the chains from the gallows where the criminal was hanged … as well as the rope … to employ in certain arts,” and forbade the use of any such object “to which superstition attributes another effect than it can have naturally.”31 Church leaders of both denominations were even more alarmed by some executioners’ attempts to cash in on their magical notoriety. In 1611, for example, Frantz’s counterpart in the Bavarian city of Passau began a long-running and especially lucrative practice by selling little folded pieces of magically inscribed paper, known as Passauer Zettel, which were reputed to protect the bearer from bullets.

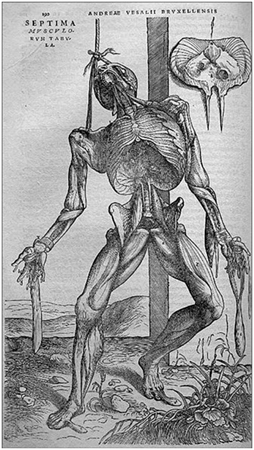

A much more familiar (and still current) use for the cadavers at Meister Frantz’s disposal was dissection for anatomical studies.32 Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo had long before requested the bodies of the executioner’s victims for this purpose—decreed permissible by Pope Sixtus IV in 1482—but the medical interest in dissection did not really take off until the publication of Andreas Vesalius’s remarkable drawings in De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Concerning the Construction of the Human Body; 1543). Accompanied by detailed commentary, the twenty-eight-year-old physician’s graceful illustrations of skeletal, nervous, muscular, and visceral systems stunned the medical establishment. Almost immediately, medical faculties across Europe began to devote lectures and endowed chairs to the study of human anatomy, convinced by the observations of Vesalius and other pioneers that much of what they had previously taught—received knowledge that dated back to the second-century Greek physician Galen—was inadequate or outright wrong. A century later, eleven German universities, including Altdorf near Nuremberg, boasted their own anatomical theaters, and the practice of medical dissection was ubiquitous.33

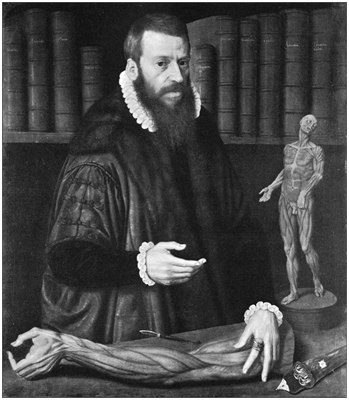

The human muscular system, one of almost two hundred detailed illustrations from Vesalius’s 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica. Note that even the celebrated expert uses a recently hanged criminal as his model.

Demand for the corpses of executed criminals accordingly rose steadily over the course of Meister Frantz’s lifetime. By the early seventeenth century, the trade in human cadavers and body parts had reached a feverish pitch. Shortly after Meister Frantz’s death, the citizenry and councilors of Munich were scandalized to learn that their appropriately named executioner, Martin Leichnam (“cadaver”), before handing over the corpse of a beheaded child murderer to her parents for Christian burial, had first sold off various body parts, including her heart, which was ground into a curative powder.34 Medical students from the University of Altdorf apparently always asked Frantz or his successors for permission before taking away executed bodies, but their less scrupulous peers elsewhere frequently staged unauthorized midnight raids of cemeteries and execution grounds. The most infamous body snatcher in the empire was undoubtedly Professor Werner Rolfinck (1599–1673), whose fondness for pilfering the local gallows led his medical students at the University of Jena to coin a new verb for the practice in his honor: “rolfincking.”35

Meister Frantz’s own keen interest in human dissection was uncommon among executioners and offers further evidence of his higher medical ambitions. Since 1548 the Nuremberg city council had restricted “the cutting up of poor executed victims” to a few physicians, and then “so long as only a few persons were present.” Three years before Frantz Schmidt’s arrival in Nuremberg, Dr. Volker Coiter was permitted to dissect two thieves and give the fat to the executioner for his medical supplies.36 This traditional division of labor and body uses was probably what city magistrates had in mind when they granted the new executioner’s request in July 1578 “to cut up beheaded bodies and take what is useful to him in his medical practice.”37 Yet in his journal’s account of how he dealt with the body of beheaded robber Heinz Gorssn (aka Lazy Hank), twenty-four-year-old Frantz is careful to specify I later dissected [the body].38 Schmidt rarely used the first-person pronoun in his journal, so it seems clear that in this entry the young executioner wished to commemorate a significant personal achievement. He explicitly records only three similar occasions—in 1581, 1584, and 1590—and the last time clarifies his intentions with the phrase dissected (adominirt) or cut up. It could be assumed that Frantz had simply appropriated the more serious language of anatomy to describe his own carvings, except that these are the same words he used when he handed over the body of the thief Michel Knüttel to the local physician Dr. Pessler for a full postmortem in 1594. His interest, in other words, was not merely in extracting usable body parts but in exploring human anatomy itself—the same as with any other physician.39

Volker Coiter (1534–76), municipal physician of Nuremberg. Coiter, like his successor Joachim Camerarius the Younger (1534–98), was an anatomy enthusiast, at one point even temporarily banished from the city on account of grave robbing (1569).

Of course there were serious limitations to the discoveries an amateur anatomist might make, even one aided by popular versions of Vesalius’s work and his own healing experience—not to mention a reliable supply of fresh cadavers. Frantz’s curiosity about human anatomy was shaped by the time in which he lived, an era when most laypeople were fascinated by oddities and anomalies but uninterested in—or unaware of—the possibility of organizing their observations into any kind of theoretical system, a pursuit that was left to natural philosophers and theologians. His methodical observation of his victims’ bodies, like his interest in their character, also does not surface in the journal until the second half of his life. In his early years, for example, Frantz might note that two brothers and their companion were three strong young thieves or note in passing that an executed robber only has one hand.40 We also learn that the barber Balthasar Scherl was a small person, had a hump in the front and back and that the beggar Elisabeth Rossnerin had a crooked neck.41 Years later, he writes with an earnest amateur’s precision that the beheaded thief Georg Praun (aka Pin George) had a neck two spans long and two handsbreadth thick [approximately nineteen by eight inches], that Laurenz Demer (aka the Long Farmer) was two fingers less than three Ells in height [i.e., about 7' 4"], and that the flogged Simon Starck has 92 pockmarks—all facts that could only have been ascertained by his own punctilious postmortem examination.42 The only time that Meister Frantz’s air of scientific dispassion eluded him was following the decapitation of thief Georg Praun, when his head turned several times [on the stone] as if it wanted to look about it, the tongue moved and the mouth opened as if he wanted to speak, for a good half quarter of an hour. I have never seen the likes of this.43 Like most early modern chroniclers, the astonished executioner does not offer an explanation, only a wonder worthy of recording.

Black magic

The healing expertise of executioners, as well as their conversancy with the illicit practices of the criminal underworld, lent the profession an aura of authority on the subject of the dark arts. In popular folklore, executioners and their magical swords (drenched in the blood of recently executed young men) could prevail against vampires and werewolves as well as summon spirits of the dead or exorcise ghosts from houses. In one typical folktale of the day, the persistence of an especially vexing house ghost prompts a showdown between a Jesuit exorcist and an executioner, with the latter ultimately claiming victory by trapping the troublesome spirit in a sack and later releasing it into a forest. Dramatic performances of this sort appear but once in the chronicles of sixteenth-century Nuremberg, in 1583, with Frantz a mere spectator to an officially sanctioned demonic exorcism by a Lutheran cleric.44

Of course, in the frenzied atmosphere of the pan-European witch craze of approximately 1550 to 1650, any association with magic—even medicinal—could prove quite dangerous. Many people presumed executioners themselves to be “secret sorcerers” and “witch masters,” particularly during the peak witch-panic years of the early seventeenth century, when all magical practices came under suspicion of diabolical origin. Though ultimately vindicated, Frantz’s Munich counterpart never fully recovered from his 1612 imprisonment for illicit magic (based on evidence brought to the courts by a Jesuit accuser). Even Schmidt’s own successor would be admonished for his involvement in “magical business” and threatened with banishment “or worse” should the council learn that he had made any contact with “the evil spirit.” Other professionals were less fortunate, most notably the widow of a later Nuremberg Lion, who was convicted and burned alive for witchcraft in the city’s only case involving an alleged diabolical pact and sex with the devil.45

More typically, professional executioners in Meister Frantz’s day served as the indispensable allies of self-proclaimed witch finders. Johann Georg Abriel, Frantz’s counterpart in Schongau, and Christoph Hiert of Biberach were themselves highly sought-out experts in finding the so-called witch’s mark, and helped to advance many witch hunts in Bavaria and Upper Swabia during the 1590s. Other executioners played similarly pivotal roles in producing confessions under torture and spreading the panic. Southern Germany in fact saw more executions for witchcraft than any other region in Europe—perhaps 40 percent of the grand total of sixty thousand—and Franconia in particular was ground zero of the witch craze, most infamously as site of the Bamberg and Würzburg panics of 1626–31 that resulted in the executions of more than two thousand people.46

In this respect, Frantz and his city represented an oasis of restraint amid the enveloping madness. Until the late sixteenth century, Nuremberg had witnessed only one execution for magic ever, and that was more properly a case of accidental poisoning by what was intended to be a love potion, nearly six decades before Frantz Schmidt’s arrival.47 By July 1590, though, even the city on the Pegnitz began to show some vulnerability to the hysteria sweeping the region. The city council reacted swiftly, but in contrast to the leaders of other territories, by arresting and imprisoning Friedrich Stigler, a banished Nuremberger and former executioner’s assistant in Eichstätt, for having brought accusations against some citizens’ wives here that they were witches and he knew it by their signs … also said that they gave magic spells to people.48

Stigler, who boasted considerable expertise from his work with Frantz’s counterpart in Eichstätt, claimed to have identified eleven witches just on the street where he resided, specifically five older women and six “apprentice girls.” During his interrogation, which included a session on the strappado under Meister Frantz, the newly arrived witch-hunt veteran claimed that he had initially rebuffed all local citizens’ appeals for help in detecting witches in Nuremberg, demurring that the city “had its own executioner” for such matters. If this remark was intended to incriminate Frantz Schmidt for being soft on witches, it had the opposite effect on his loyal employers, who likewise regarded all allegations of witchcraft with deep skepticism. Undaunted, Stigler next told how he was finally persuaded by the unrelenting petitioners to share his anti-witchcraft expertise, which he did by selling them small bags of blessed salt, bread, and wax for one ort (¼ fl.) each. According to Stigler, the bags, which he had been taught to make by his executioner master at Abensberg, both protected one from witches and could be used to find the devil’s spot on a witch, which—as everyone knew—was impervious to the pain of a needle prick.49

The presiding magistrates gave no credence whatsoever to Stigler’s “false accusations … made out of pure, brazen, wantonness,” and showed more concern over his own familiarity with magic, not to mention his three wives. More than anything, it was their determination to prevent a local panic that ultimately led them to pronounce a death sentence for the “godless” Stigler, “on account of having given rise to all kinds of unrest, false suspicion, and strife among the citizenry as well as various superstitious, godless spells and conspiracies and other forbidden magical arts and methods elsewhere.”50 On July 28, 1590, he was out of mercy beheaded by Meister Frantz.51

The burning alive of three accused witches in Baden. The pan-European witch craze coincided almost exactly with Frantz Schmidt’s lifetime (1574).

The Nuremberg government’s decisive response to its first serious encounter with witch paranoia received the full support of its executioner. Given the popular association of executioners with the dark arts, Frantz Schmidt had special motivation to see such a disreputable fellow professional punished. That Stigler wittingly did [the accused women] wrong earned him still more disdain from the slander-sensitive Meister Frantz. Above all, Nuremberg’s executioner appears to have shared the wariness of his superiors toward witch accusations in general, as well as their profound fear of the disorder and lawlessness that inevitably ensued. He followed with amazement and likely disgust the mass trials and burnings in the Franconian countryside where he had traveled as a journeyman. Like Stigler, Frantz knew from his experience in Bamberg about the methods of witch finders as well as the genuine danger of coerced confessions at the hands of a skilled torturer. The pivotal role of the professional executioner in such spurious proceedings must have been for him a source of discomfort, perhaps even shame.

Over the next two decades, Nuremberg’s magistrates continued to fervidly resist the panics seizing neighboring territories. Less than eighteen months after Stigler’s execution, the tortured confession of a suspected witch in the neighboring margravate of Ansbach led to the arrest of two women from villages in Nuremberg’s jurisdiction. After a painstaking investigation of the charges involved in both cases, Nuremberg’s jurists found insufficient justification for torture and recommended dismissal of charges. Upon receiving Meister Frantz’s further assessment that both women were of too advanced an age to withstand physical coercion anyway, the city council ordered both women released. The following year, when officials of the margravate learned of the covered-up suicide of an alleged witch in Fürth (admittedly within their legal jurisdiction), they not only demanded that her body be exhumed and burned, but also that all her family’s property be confiscated. Once more eager to avoid triggering a panic, Nuremberg’s jurists countered that neither the charges against her nor the nature of her death could be definitively established, and thus continued to back the aggrieved widower and his son during several additional legal assaults from the margravate. In subsequent years, the council released three Altdorf men after confiscating their “magical books and decks of cards” and summarily dismissed two old women accused separately of employing magical healing. Only the convicted perjurer Hans Rössner, who repeated Friedrich Stigler’s mistake of spreading false rumors and accusations of witchcraft, received punishment, although unlike his doomed predecessor he escaped with time in the stocks and lifelong banishment (under threat of execution, should he return).52

Neither Meister Frantz nor his superiors denied the efficacy of magic per se, but they focused instead on whether it had been used in conjunction with any harmful deeds, known as maleficia. Schmidt impassively notes that Georg Karl Lambrecht, the last poor sinner he executed, also occupied himself with magic spells, but since no maleficia were established, it was not one of the crimes mentioned in his official verdict.53 He considers it relevant that Kunrad Zwickelsperger, who committed lewdness with the married Barbara Wagnerin, gave two fl. to an old sorceress that she might cause [Wagnerin’s husband] to be stabbed, struck down, or drowned, but Zwickelsperger’s ultimate condemnation is based on the more pertinent evidence that he also convinced his lover to poison her husband repeatedly (as well as that he slept with her mother and three sisters).54 Often Frantz mentions “magical” curses to establish character and motive for subsequent violent action: a young knacker who publicly hexes his treacherous former companion so that he would immediately die; or a village bully who threatens his neighbors that he would burn their house down [and afterward] cut off their hands and hide them in his breast.55 Anticipating the conclusions of historical anthropologists centuries later, Frantz recognized that such curses and threats often represented the empty bluffs of the powerless. When the arrested thief Anna Pergmennin threatened that she would fly off next to an old broom-maker hag on a pitchfork, Schmidt adds sardonically, but nothing happened.56 His apparent openness to the possibility that something might have happened distinguishes his skepticism from ours, but his steadfast imperviousness to witch hysteria matches our own.

The similarity of Frantz Schmidt’s outlook to that of contemporary physician Johann Weyer suggests that the executioner was familiar with the latter’s De Praestigiis Daemonarum (On the Illusions of Demons; first German edition in 1567), either indirectly or through his own reading. The most famous (and consequently vilified) early opponent of the witch craze, Weyer likewise refused to rule out the efficacy of magic, but simultaneously argued that the great majority of self-proclaimed witches were either self-deluded or outright frauds. The remainder were intentional poisoners—a capital crime sufficient unto itself. Like their contemporary Michel de Montaigne, Weyer and Meister Frantz showed acute awareness of the power that emotions could exert on the human imagination, both in the case of alleged victims and alleged perpetrators.

Certainly Meister Frantz recognized the genuine psychological agony of some poor sinners who came before him and had convinced themselves of inescapable diabolical entanglements. During his imprisonment in the Hole, the thief Georg Prückner gave out that he had received from the night watchman at Kreinberg something against wounds which he must eat—having sworn in return, however, never again to think of God nor pray to Him—which he did and gave himself to the devil. He tried to break out of the Hole and indeed behaved wantonly, as if the evil spirit tormented him. The executioner’s judicious and indeed … as if succinctly conveys his simultaneous acknowledgment of a diabolical power and his own conviction that Prückner was in fact delusional. Neither Frantz nor his chaplain colleague, Magister Müller—who complained of being kept awake at night two blocks away in the Saint Sebaldus parsonage because of Prückner’s loud ravings—treated the tormented soul as an actual disciple of Satan, and indeed agreed that he behaved in a Christian manner [in the end].57 Schmidt believed, in other words, that the temptations of a spiritual devil could prey on a weak mind, even if witches’ sabbaths and other physical encounters remained pure fantasy. Another disturbed inmate, the thief Lienhard Schwartz, unsuccessfully tried to kill himself in prison, first with a knife and later by hanging with his torn shirt, saying a voice spoke to him, though he saw nobody, telling him that if he surrendered to him he would soon help him. Meister Frantz pointedly adds, at this he fell into repentance, but if the voice had called again it might have happened [otherwise].58 On the source or reality of the voice, the executioner remains mute.

Any residual awe of so-called dark magic from his younger days was effectively demolished by Frantz Schmidt’s lengthy experience in the torture chamber. He knew intimately of the persistence of countless spurious beliefs among professional criminals, despite not a single example of efficacy. Attempts to acquire invisibility or protection through severed body parts, pieces of the gallows, or other talismans were invariably presented in his journal as evidence of pathetic gullibility. Like disreputable companions and confiscated burglary tools, magical charms could also provide evidence of illicit activities and intentions. During one interrogation, the incorrigible honey thief Peter Hoffman claimed repeatedly that the skull and bones found on him during his arrest were not intended for nefarious purposes, but rather as a means of healing epileptics. (He also denied magically transporting his estranged female companion across great distances, but eventually acknowledged that he had appropriated her undergarments in a failed attempt at love magic designed to bring her back to him.) Schmidt notably declines to make use of such harmless “incantations and conjurations” to further blacken Hoffman’s name in his journal, instead mentioning only his multiple thefts and adultery.59 Even the notorious Georg Karl Lambrecht, pushed hard to admit that “he is himself a true sorcerer and conjurer of devils … addicted to the diabolical arts,” in the end owns only to buying a charm and some enchanted slips of paper to protect himself against gunshot. Moreover, after having tested one “magically protective” skull on a dog (which promptly died from multiple bullet wounds), he concludes that “the deeds and boasts of these vagabonds were all pretended and imagined [and] he did not desire to have anything further to do with them”—a conclusion his executioner had apparently reached long ago.60

The great majority of the so-called magical experts that Meister Frantz Schmidt encountered during his career could be classified quite simply as frauds. He whips out of town Cunz Hoffmann, who gave himself out as a planet reader [i.e., astrologer] and palm reader, as well as four divining Gypsies, and the fortune-telling and treasure-finding Anna Domiririn, who in one day [obtained] about 60 fl. and five golden rings from Frau Michaela Schmiedin. Like many traveling folk, the thief and cardsharp Hans Meller supplemented his income with occasional commerce in magical objects: among other practices, he was convicted of coating yellow turnips in fat, sticking hair on them, and selling them as mandrakes for healing purposes.61 The procuress Ursula Grimin (aka Blue) said she was a cunning woman and could tell which man carried a child, informing a customer that if he wanted to avoid an unwanted pregnancy, he had to shove quickly into only her maid; otherwise he had to wait with his paramour until [Grimin] said, “Let’s see what my little lamb chop or baby is doing,” whereupon she stood before the men, uncovered herself, and said, “Hurrah cunt, gobble up the man.” Frantz’s amusement over the gullibility of Grimin’s clients is surpassed only by his obvious enjoyment of the relatively innocent fraud of a young shepherd at Weyer, who for two years pretended to be a ghost in a house, tugging on the people’s heads, hair, and feet while they slept, so that he could secretly lie with the farmer’s daughter.62

The most shameless—and successful—magical fraud Schmidt encountered during his executioner days was undoubtedly the one-legged seamstress Elisabeth Aurholtin of Vilseck, who called herself the Digger. Claiming to be “a golden Sunday child,” she amassed a fortune of over 4,000 fl. by convincing people of all ranks that she had the ability to locate hidden treasures and liberate them from the dragons, snakes, or dogs who guarded them.63 The key to her success, in her executioner’s assessment, lay not in the devilish incantations and ceremonies [she employed]—all ineffectual gibberish—but rather in her evident gift for making the most far-fetched stories sound credible. After listening to her tale of a sunken underwater castle and its iron chest full of treasure, three initially skeptical men spent an entire day digging for a white adder, with which “she would charm the treasure so that it would float on the water.” Others wandered the countryside for days with her and her divining rod, apparently undaunted by their persistent lack of success and ready to pay still more for her special services.

Meister Frantz cannot suppress a hint of amazement at the sheer audacity of this gifted con artist or the gullibility of her greedy victims. He describes her most successful scheme in exceptional detail:

This was how she carried out her tricks. When she came into a house and wanted to cheat someone, she used to fall down as if she were ill or in convulsions, giving out afterward that she had a wise vein hidden in her leg, whereby she could foretell and reveal future events and discover hidden treasures, and that when she entered a house her veins never left her in peace until she announced these things. Also that the realms of earth were opened out before her, and that she saw therein gold and silver, as if looking into a fire. If any doubted, she asked leave to spend the night in the house, so that she could speak with the spirit of the treasure. When this happened, she behaved at night—with her whisperings, questions, and answers—as if someone were speaking to her, and gave out afterward that it was a poor lost soul in the house that could not enter into bliss until the treasure was dug up. Thus the people let themselves be persuaded by her, believing such tales because of the terrible incantations and assurances which she used, and caused the ground to be dug up. During this digging she would slip a pot full of coals into the hole and give out that she had dug it up herself. Then she commanded them to lock it up in a chest for three weeks and not touch it, and that it would turn to gold when she recovered it, [but] the coals remained coals.

Predictably, Schmidt is most shocked by Aurholtin’s fearless defiance of the prescribed social hierarchy. She defrauds many well-to-do individuals and even convinces one noble to house her and her small daughter, and two others to serve as the child’s baptismal sponsors. On other occasions she cheekily invokes one of Nuremberg’s patrician leaders as a business reference, claiming to have drawn a fountain of gold for Master Endres Imhoff out of his yard and had dug up a golden treasure, nothing less than idols of pure gold. Meister Frantz never once takes her claims to supernatural powers seriously, but he remains in awe of her prowess as a conjurer of tales.

An executioner’s legacy

Until his late fifties, Meister Frantz showed few public signs of weariness in his duties. He traveled less often for work and apparently not at all after 1611, but he continued to personally administer almost all floggings and other corporal punishments well past the age when most of his fellow executioners handed over such physically demanding work to their younger associates.64 The first trace of decline came in February 1611 when he experienced his most dramatically miscarried execution ever—requiring three strokes to decapitate the incestuous and adulterous Elisabeth Mechtlin. Spectators expressed shock at the fifty-seven-year-old veteran’s “shameful and very heinous” performance.65 The executioner’s only written acknowledgment of this widely publicized embarrassment was a single word at the end of the journal entry: botched. The following year, a particularly reviled pimp and government informer slipped from the executioner’s grasp as he was being flogged out of town and was subsequently stoned to death by an angry mob—resulting in an official investigation and unprecedented scolding of the veteran executioner.66 Two additional botched executions followed, one later that year on December 17, 1613, the other on February 8, 1614—neither of them noted as such in Frantz’s journal. There were no apparent calls for the elderly executioner’s retirement, however, and he went on to dispatch eighteen more poor sinners over the next thirty-four months.

What turned out to be Meister Frantz’s final year on the job began unremarkably, with two successful beheadings and a few floggings. Then, during the night of May 31, someone—more likely several people—tipped over the Nuremberg gallows.67 Schmidt makes no mention of the occurrence in his journal, nor did he apparently assign it any significance, assuming it was merely an act of drunken vandalism. Less than a month later, however, he records a more unnerving event that took place during the hanging of rustler Lienhard Kertzenderfer (aka Cow Lenny) on July 29, 1617. According to one chronicler, the executioner’s first attempt to mount the gallows was thwarted by “a sudden, stormy wind,” which swept the two ladders from the gallows, so that they had to be retrieved and tied fast. Even then Meister Frantz and the thoroughly besotted poor sinner could hardly move forward amid the powerful gusts, which “roared and raged so terribly that it blew and threw people to and fro.” But at the moment the condemned man, who had refused to pray, was finally dangling from the rope, “the wind calmed and the air became completely still.” Just then a hare came out of nowhere and ran under the gallows and through the crowd, pursued by a dog “that no one recognized” (and that many spectators took for a demon pursuing the soul of the poor sinner). A shaken but more circumspect Meister Frantz demurred that what kind of hare it was or what kind of end he had God knows best.68

Seemingly undeterred by omens or by old age, Meister Frantz hanged three more thieves over the next five months and flogged two before coming to what would be the final execution of his career. The prescribed live burning of counterfeiter Georg Karl Lambrecht, on November 13, 1617, was a rare event for Nuremberg and only the second execution by this method that Frantz Schmidt had performed in more than four decades of service. Ever anxious to orchestrate the violence, Nuremberg’s council ordered the executioner to speed the condemned man’s death either by placing a sack of gunpowder around his neck or by strangling him first, “albeit unnoticed by the crowd.”69 Meister Frantz replied that he preferred strangulation since the gunpowder might either misfire or explode with such force as to endanger those nearby. As usual, the councilors deferred to his expertise, underscoring only that the strangulation had to be done in such a way “so that the crowd doesn’t notice.” Efficiency rather than mercy drove their decision; the spectators’ terror of live burning needed to be preserved.

Lambrecht’s execution should have been one of Schmidt’s smoothest. During the previous five weeks, according to the prison chaplain, the poor sinner “had talked more with God than with humans,” weeping and praying incessantly.70 After making a full confession and receiving communion in his cell five days before his scheduled execution, Lambrecht had refused “to contaminate or stain his body with food or drink.” His final procession was likewise exemplary, the poor sinner alternately praying aloud and asking those he passed for forgiveness. Most important to Meister Frantz, the condemned man made one final confession and plea for forgiveness before kneeling to recite a Paternoster and other prayers.

In the end, Frantz had decided to rely on both a gunpowder sack and secret strangulation, disregarding his own argument to the magistracy. Perhaps he had a premonition that the secret garroting might fail, but he could not have anticipated that both measures would misfire, producing the agonizing and spectacular failure that we witnessed at the book’s outset. True to form, Schmidt does not implicate his Lion, Claus Kohler, for the bungled strangulation, either to his superiors or in his private journal. In a bit of deft revisionism, he in fact records the execution as a successful live burning, effectively denying any mishaps whatsoever. He also does not identify the execution as his last—contrary to later manuscript versions of the journal—and soldiers on, even personally administering a flogging three weeks later and another (his last) on January 8, 1618.

The final punctuation to a forty-five-year career was a decidedly anticlimactic affair. On July 13, 1618, the longtime sacristan Lienhard Paumaister reported to the city council that the venerable Meister Frantz was too infirm to carry out either of the two executions planned for the next week. Paumaister did not specify the nature of the illness, but Schmidt himself carefully annotates that it began nine days earlier. When asked to suggest a “competent person” to replace him “until he is returned to health,” Frantz remained markedly noncommittal, replying that he knew of no one to recommend but that “my lords” might make inquiries at nearby Ansbach or Regensburg. If the veteran executioner intended to keep his options open, these hopes were quickly quashed. Anxious to carry out the impending death sentences of a thief and a child murderer, his superiors acted in typically expedient fashion when a week later they received an unsolicited application from Bernhard Schlegel, the executioner of Amberg, a nearby provincial town. After a cursory look at Schlegel’s credentials, they offered him 2½ fl. per week salary plus free lodging. The job candidate immediately demanded, with a directness Nuremberg’s councilors would come to know well, the same salary as Meister Frantz (3 fl. per week), plus a year’s supply of wood and immediate possession of the Hangman’s House. Still awaiting a response from Regensburg, the council agreed to Schlegel’s terms and had him sworn in as a lifelong employee within two weeks of Meister Frantz’s initial message. One week later the new executioner beheaded his first two victims on Nuremberg’s Raven Stone.71 The final entry in Frantz’s journal of nearly a half century is typically succinct: On July 4 [1618] I became ill and on St. Laurence’s Day [August 10] gave up my service, having held and exercised the office for forty years.

The apparent ease of Frantz’s retirement belies the onset of a power struggle between the old executioner and his replacement that would continue for years to come. The seemingly unsentimental indifference of Meister Frantz’s superiors to his forty years of exemplary service likewise obscures their continuing deference to him in that contest, particularly as the favorable contrast to his successor became increasingly obvious. That loyalty was evident from the time of Schlegel’s arrival, when Nuremberg’s magistrates made only one qualification to his list of demands: that he give Meister Frantz and his family sufficient time to locate another residence and clean out their current home for him. This seemingly reasonable and innocuous compromise would spawn a bitter lifelong feud between the two executioners and their families that would end only when both men were dead.

Within two days of his first executions in Nuremberg, the newly hired Schlegel complained that his temporary lodging in the former pesthouse was still (!) not ready and that staying in an inn presented a great inconvenience and expense. The council immediately responded with a bonus of 12 fl. (one month’s salary) and delicately “made inquiries of Meister Frantz” as to when he expected to vacate the Hangman’s House. In the first countersalvo of an extended stalling campaign, Schmidt replied that he fully intended to buy a new house but was unable to undertake the task because of his current infirmity. Unwilling to press the venerated veteran, his superiors instead ordered the acceleration of renovations to a large third-floor apartment for the new, married executioner in a building he and his wife would share with twenty single male renters and the occasional chain gang. As a further concession to an apparently indignant Schlegel, the council granted the new executioner several extended leaves during the next few months “to settle his affairs” as well as an additional 12 fl. for moving expenses.72

Over the next year, the councilors’ annoyance with their new employee grew steadily, as did their appreciation of his predecessor, the realization gradually dawning that Bernhard Schlegel was no Frantz Schmidt. On the issue of salary alone, Schlegel was unrelenting. Whereas Meister Frantz requested a raise only twice in forty years (the last time in 1584), Meister Bernhard lamented his own inadequate compensation regularly—sometimes several times within a year. Occasionally the council granted him a onetime bonus of 25 fl.; other times they denied his requests outright, with ever more strident language.

One petition for a loan of 60 fl.—likewise refused—suggests that the new executioner was not merely greedy but probably strapped with insurmountable debts, likely brought on by gambling, drinking, or other “frivolous living”—a marked contrast to the sober lifestyle of his esteemed predecessor. Less than a year after his arrival in Nuremberg, Schlegel was summoned before the council: he had taken part in a bar fight at the fencing school, an altercation that began when Schlegel’s drinking companion was harassed by fellow craftsmen for sharing a table with the executioner. While dismissing the traditional notion of contagion and reaffirming the respectability of the potter in question, the city fathers also chided Schlegel to “conduct himself more temperately and to not get involved in citizen drinking bouts at public taverns.”73

Succeeding a venerated icon, famous for his modest living, piety, and sobriety, was bound to be difficult for anyone, but much more so for an outsider widely perceived to be grasping, confrontational, and living beyond his means.74 The specter of Meister Frantz clearly haunted Meister Bernhard from the day of his arrival in Nuremberg, and the latter was likely dogged by frequent unflattering comparisons to his predecessor that began to erode public confidence in his professional expertise. Within a few weeks of reprimanding Schlegel for his public fraternizing, the city council “fervently admonished” him to do a better job of maintaining order at public executions. Less than a year later he was chided for an especially prolonged hanging, during which Schlegel knocked over the ladders and was stranded on a crossbeam of the gallows while the poor sinner slowly choked in agony, crying out the name of Jesus for several minutes before expiring. Eventually the veteran Lion rescued the bumbling executioner, but only after both received a thorough pelting with frozen mud balls by the outraged crowd.75

In 1621, despite grave misgivings, the worn-down city councilors finally conceded the right of citizenship to Schlegel, a privilege that Frantz had won only after fifteen years of service but which Meister Bernhard had requested repeatedly since his arrival in Nuremberg three years earlier.76 To their dismay, the new executioner’s performance on the scaffold showed no improvement. After Schlegel blamed still another bungled execution on the Lion, the council upbraided him and threatened outright dismissal unless he immediately improved his performance and “banish[ed] his gluttonous ways.” Aware that his employers were in fact loath to undertake the search for a replacement, Meister Bernhard grudgingly endured their periodic scolding, including humiliating reminders before executions “to take [the matter] earnestly and not to bungle it.”77

Relentlessly assaulted by unfavorable comparisons to the great Frantz Schmidt, Schlegel took out much of his anger on the former executioner for his continuing resistance to vacating the Hangman’s House. Here the new executioner had a legitimate grievance, and it is hard not to sympathize with his frustration about being consistently outmaneuvered by a wilier and better-connected rival. Perhaps because of Schlegel’s frequent complaints on so many other issues, his laments over the Schmidt family’s continual squatting in the home that had been promised to him fell on deaf ears for nearly seven years. Possibly the magistrates hoped that the matter might eventually be resolved in relatively easy fashion by the elderly Schmidt’s death.

Finally, in the summer of 1625, the devastation of war, an influx of refugees, and the arrival of yet another epidemic triggered a severe housing crisis that forced the city councilors to act against the still vital seventy-one-year-old Meister Frantz. Desperate for emergency hospital space, the councilors evacuated the former pesthouse where Schlegel and his wife had been residing and began the eviction of his predecessor from the Hangman’s House, offering to pay all the Schmidt family’s moving expenses. Again Frantz repeatedly demurred, claiming that he had been promised the house for life—a dubious assertion that contradicted his own declared intentions to relocate seven years earlier. The tactic nevertheless appeared to work and the councilors directed Schlegel to find alternate housing on his own. When a clerk from the criminal bureau subsequently reported that he found no trace of any such promise in the official records, Schmidt fluently switched tactics. He now claimed to have identified a suitable new house two blocks away, on Obere Wöhrdstrasse, but required financial help from the council to cover its yearly mortgage of 75 fl. The residence itself—actually two conjoined houses, owned for the last six decades by a prominent goldsmith—had a steep purchase price of 3,000 fl. and also required a sizable down payment of over 12.5 percent. Desperate for resolution, the council did not blanch at the cost but merely verified that the former executioner’s investments earned a yearly interest of only 12 fl. before agreeing to grant him an annual stipend of 60 fl. in perpetuity. Shortly after Walpurgis Day (May 1) 1626, Frantz Schmidt finally vacated his home of nearly fifty years and the jubilant Bernhard Schlegel moved in.78

Fresh from this victory, Schlegel turned his resentment of the revered Meister Frantz to their competition in the medical sphere. Until then, the new executioner’s conflicts had been mostly with local barber-surgeons, who early on complained about his aggressiveness in pursuing their clients.79 At one point the council admonished him for consulting on a case involving magic and mental illness, reminding him that he was to confine his medical work to “external injuries.”80 Again, Schlegel clearly lacked his predecessor’s diplomatic skills, and his professional reputation suffered as a result. On a few occasions, he even suffered the humiliation of having his prognoses formally second-guessed by Meister Frantz.81 Within a year after taking possession of the Hangman’s House, Schlegel complained to the city council that the former executioner was taking away too many of his clients and demanded both a formal sanctioning of Schmidt and the construction of a new entrance for his own patients, away from the dishonorable pig market. Both requests were denied and Schlegel was reminded that “since Frantz Schmidt helped him for many years, he should be able to tolerate him.”82 Rebuffed yet again, the exasperated executioner lodged no more formal complaints against his venerated predecessor but no doubt looked with anticipation toward the old man’s imminent demise.

A father’s legacy

The single greatest indignity suffered by Schlegel was the moment of ultimate triumph for Meister Frantz and his children. In late spring 1624, while still ensconced in the Hangman’s House, Meister Frantz Schmidt wrote to the emperor Ferdinand II (r. 1618–37), requesting a formal restitution of his family’s honor. Direct appeals to the imperial court were not unheard-of, but why did Frantz choose this particular moment to seek the final completion of his quest? Perhaps the retired executioner needed such an endorsement to purchase a new house or his sons had requested help in obtaining honorable craft positions. It’s possible that Meister Frantz was even thinking of his eleven-year-old granddaughter, who had just moved in with him and his adult children. An even more intriguing question is why he waited six years after his retirement to write such an appeal. Given how important the restoration of family honor was to Schmidt, it’s likely that he had been trying to draft and send the missive for some time, but that forces beyond his control—reluctance on the part of his patrician backers or some other local political issue—had until then thwarted him.

Whatever the reason for its timing, this remarkable document—no more than fifteen pages long in its original form—provides not just an old man’s summary of his life’s work but also a final, telling illustration of the personal networking and powers of persuasion that had made that life such a success. Frantz’s petition is a model of rhetorical finesse, skillfully alternating his many accomplishments on behalf of the emperor and his subjects with a personal plea for sympathy over the misfortune suffered by him and his family. Like his Meisterlied on the healing of King Abgar, the petition was without a doubt composed with help, probably from a professional notary. The reasoning and sentiments, however, are pure Meister Frantz. After the formulaic obeisance, he begins his appeal by invoking the responsibility imposed on secular authorities by God Himself to protect the pious [and] law-abiding from all violence and fear [as well as] to punish the unruly and evil with the appropriate severe punishment, so that peace, calm, and unity might be preserved. Meister Frantz goes on to establish the divine origin of the office of executioner, citing the Old Testament account of the Israelites and their ritualistic execution by stoning as well as the imperial dictates of the Carolina. And yet, he writes, despite the legitimacy and necessity of his work, the profession of executioner represented a vocation thrust upon him by an unfortunate incident, which I cannot refrain from recounting.

Frantz’s subsequent appeal to the emperor’s compassion contains the most introspective and personally revealing lines he ever wrote. Finally out of the public spotlight, he is surprisingly frank about the deep shame that has haunted his family ever since Margrave Albrecht callously forced Heinrich Schmidt to perform those long-ago executions on the market square in Hof. Just as unfair, and as much as I would have liked to shake free of it, he writes, the family dishonor forced him into the office of executioner as well, a cruel contradiction of his own natural calling to medicine. And now Meister Frantz turns to the final reason his restitution request should be granted: Medicine, he writes, is the vocation he has managed to practice for forty-six years, next to my difficult profession, helping with my healing over fifteen thousand people in Nuremberg and the surrounding lands—with the help of the most high and eternal God. Healing is also the trade he has taught to his own children, he writes, out of true paternal responsibility with good discipline … just as my father taught me, despite the difficult and universally despised office forced upon both of us. Moreover, he has always applied his medicinal learning in useful and honorable ways, including the healing of certain highly placed imperial representatives, whom he names in an appendix, together with nearly fifty noble and patrician clients, more than a third of them women.

Only at this point does Meister Frantz return to his forty years of service to the emperor and his Nuremberg representatives in the role of executioner, which I undertook and administered without the slightest concern for the danger to my life. During that entire time, there were no complaints about me or my executions and I voluntarily left office about six years ago on good terms, on account of my age and infirmity. An attached recommendation from the Nuremberg city council confirms that Schmidt was well-known for his calm, retiring life and behavior as well as his thriving medical practice … and his enforcement of imperial law. In consideration of his many years of service in both law enforcement and medicine, as well as his thirty-one years as a Nuremberg citizen, Frantz Schmidt closes by humbly requesting the restoration of his family name, which will finally lift the stigma he has known all his life and open all honorable professions to his own sons.

Sometime after June 9, 1624, Frantz paid a private courier to carry the sealed petition to the imperial court in Vienna, possibly as part of the city council’s regular diplomatic pouch. After only three months, an ornately inscribed and wax-sealed reply arrived at the Hangman’s House, also delivered by private courier. The original of Frantz’s petition has not survived, but this formal response to it remains preserved in Nuremberg’s Staatsarchiv (thanks to Schmidt’s immediately filing it with the city’s chancery on September 10).83 Ferdinand himself had probably never even seen the former executioner’s appeal, and the entire affair was likely handled at least a few levels of bureaucracy below the emperor, possibly including the imperial signature itself. Following a reiteration of Frantz’s request, though, the brief document culminated in the words he had longed to hear his entire life:

On account of the subservient petition to us from the highly esteemed mayor and council of the city of Nuremberg, the inherited shame of Frantz Schmidt that prevents him and his heirs from being considered upright or presents other barriers is, out of imperial might and clemency, hereby abolished and dissolved and his honorable status among other reputable people declared and restored.84

Little matter that in the end the decision was less influenced by the executioner’s heartfelt plea or his long service than by the dignitaries in his corner: Meister Frantz knew the ways of his status-obsessed society. He had achieved his goal; his father’s dishonor had been transformed into his sons’ honor. It was not the executioner’s sword that he would pass on to them but the physician’s scalpel.