CHAPTER 10

“WHO ARE THESE PEOPLE?”

SAVANNAH BOWEN MAY HAVE STARTED OUT her senior year as a tennis star poised to attend an elite white university, but studying under Miss Cadet-Simpkins, her English AP 12 teacher at Pelham Memorial High School in an affluent suburb outside New York City, was complicating things. The change of heart began as Miss Cadet-Simpkins, the first black teacher Savannah had ever encountered during all her years of schooling, introduced the mostly white class to Toni Morrison’s Beloved and For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf by Ntozake Shange. “Those books were powerful,” Savannah said. “It was the first time I had ever read a book by a black person in school. I went to class every day loving it. The other students hated it.”

Actually, the awkwardness was telling when Miss Cadet-Simpkins assigned several small groups in the class to read, review, and ultimately recite various Harlem Renaissance poems. Savannah’s group took on “Yet Do I Marvel” by Countee Cullen, the morose and militant sonnet that compares the most tragic characters in Greek mythology to Cullen’s own lot as a black poet. When it was time for her group to recite the classic, her white colleagues froze, admitting to her that it felt uncomfortable assuming the voice of a black man and asking her to carry the load. How many white authors had Savannah been forced to recite during all her years in school, and these white kids couldn’t bring themselves to read a few simple lines penned by a black man? They said they were having trouble “getting into character” for this poem. Their reticence struck her as ridiculous, and racist, but Savannah plowed ahead, reciting most of Cullen’s powerful sonnet herself.

Savannah’s eyes opened wider about her classmates when Miss Cadet-Simpkins scheduled an exam that they believed was untimely based on other school obligations. Savannah was accustomed to students protesting work, but in her view her classmates’ pushback crossed the line into disrespect. “Everyone was being so rude to her,” she said. “‘You can’t do that,’ they were saying, ‘Are you crazy?’ This was the cream of the crop of the school, not some at-risk youth, and they were being blatantly offensive to this woman. It was the tone in how they responded to her authority; that’s when I realized a lot of my classmates were racists.”

There were other unsettling moments. One of them occurred after the class had finished reading For Colored Girls and Miss Cadet-Simpkins asked students whether they believed the book was written exclusively for “colored girls” or whether there were universal themes that everyone could relate to. While Savannah could not relate directly to any of the experiences in For Colored Girls, the work was, at moments, cathartic to her; the rainbow of women sharing their experiences of pain and love and hardship spoke to Savannah’s gut and validated her feelings of pride and power as a woman.

Unfortunately, Savannah’s classmates did not share her enthusiasm for the book; in fact, her white classmates resented having to read it, even admitting they had done so only because it was required to pass the class. While Savannah admired her teacher’s courage for posing the question, she loathed witnessing the Anglo-centric dialogue such a question inspired. Her peers sounded ill-informed, small-minded, and racist. “Nobody ever asked me if I could relate to Charles Dickens or Jane Eyre,” she said. “Nobody had ever asked them to relate to black people. I felt like, the fact that we were even having this conversation is a symbol of your privilege in this world.”

In fact, Miss Cadet-Simpkins had only fanned the flames by assigning her class to read the popular essay “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” by feminist scholar Peggy McIntosh, which, among other things, posits her belief that “. . . whites are carefully taught not to recognize white privilege, as males are taught not to recognize male privilege” and likens her racial advantage to “an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks.” The essay cut hard into the attitudes and emotional predispositions that Savannah recognized in her classmates. Or as McIntosh wrote about herself: “I began to understand why we are justly seen as oppressive, even when we don’t see ourselves that way. I began to count the ways in which I enjoy unearned skin privilege and have been conditioned into oblivion about its existence. My schooling gave me no training in seeing myself as an oppressor, as an unfairly advantaged person, or as a participant in a damaged culture.”

Then there was Savannah’s heated debate with some classmates about whether the nation’s racial segregation had ended; they insisted it had, while Savannah argued that segregation persisted, pointing out that most of the workers in the school’s cafeteria were Hispanic. Her classmates took offense to this, told Savannah that she was rude, and said that working in the cafeteria was good, honest labor and that it was their choice to work in the kitchen and had nothing to do with segregation. The debate dragged on through the bell and into their French class, which followed. The exchange became so heated that Savannah became emotional, breaking down in tears. “They all jumped down my throat,” she said. “I was hurt. Who are these people? Who in their right mind believed this?”

A couple of days later, Miss Cadet-Simpkins took Savannah aside and privately raised the incident with her. Savannah shared that she was starting to feel alienated among her peers, and that lately she found herself wondering whether her white friends harbored racist beliefs. Miss Cadet-Simpkins calmly reassured her that her feelings were likely not altogether unwarranted, and hardly uncommon for a young girl in such social circles. The talk did not quite soothe Savannah’s heartache, but having her feelings validated offered some sense of renewal.

There were other minor incidents that rubbed Savannah wrong, too. Like the boy who proclaimed that there were only “two kinds of black people: high-performing black people and low-performing, and no in between. While I’m sure he has long forgotten those words, I will never forget them.” And another racially mixed boy who preferred to be called Hispanic, yet joined Savannah in accepting an award for academic achievement for black students. “I’m like, ‘but he doesn’t even present himself as a black man,’” she said. “I mean, I could have taken that photo op by myself.”

Once, Savannah overheard a younger classmate, a racially mixed girl of Caucasian and East Indian descent, wishing for an eradication of affirmative action in education and how such policies caused teachers to look down on her and assume that she wasn’t as bright as she was. Savannah, who worked on the Pel-Mel, the high school’s newspaper, was so infuriated by the girl’s stance that she wrote an editorial, essentially arguing how wrongheaded it would be to get rid of a program whose sole purpose was to help uplift minorities who have been historically disadvantaged from unfair and unjust treatment. The piece drew praise from a few administrators and faculty. Savannah’s friends never mentioned it.

It was also around that time that Miss Cadet-Simpkins began encouraging Savannah to apply to her alma mater, Spelman College. Savannah, having spent most of her schooling at all-girls academies, wasn’t sold on attending another. But for the first time, she began seriously thinking about her dad’s alma mater, Howard University.

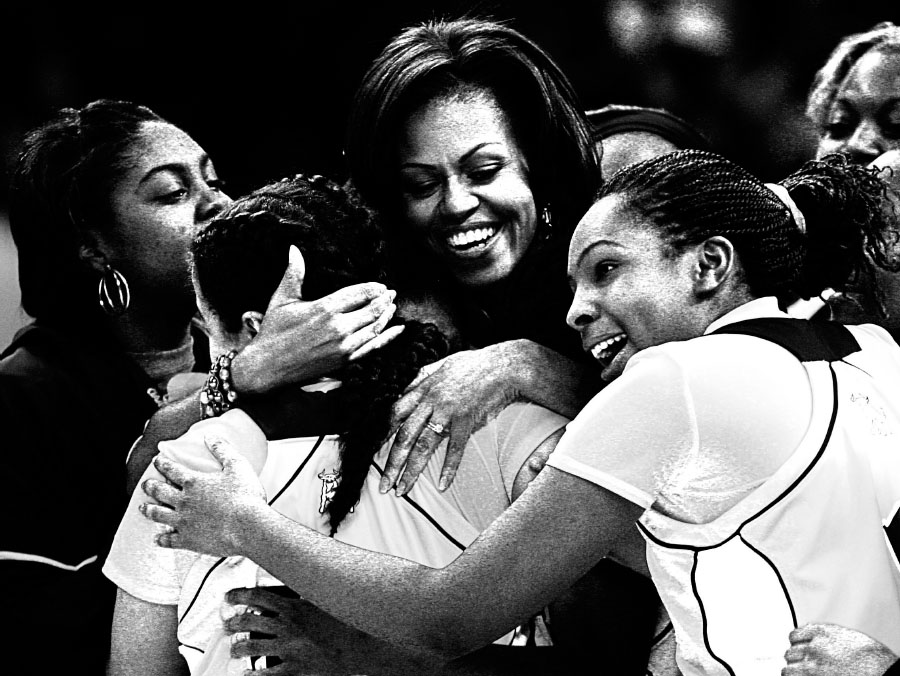

First Lady Michelle Obama embraces members of the Johnson C. Smith ladies’ basketball team during a “Let’s Move!” physical fitness promotion between games at the CIAA basketball tournament in Charlotte, N.C., on Friday, March 2, 2012.

(Nell Redmond/AP)