Historical views

According to the ancient Greeks, the mountains were the home of the Gods – in Greek mythology, Mount Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece, was where Zeus held court with the other gods, and no human would dare to go there. There seems to have been little, if any, attempt by the ancient philosophers at understanding the true nature of mountains.

In both the Jewish and subsequently Christian traditions, mountains, like the other features of the Earth, were part of the divine creation, and for centuries it was futile (and at times dangerous) to question this. The serious scientific approach to the origin of mountains only began in the late eighteenth century with the work of James Hutton.

Hutton and Lyell

James Hutton (1726–1797)

Hutton was a Scottish scientist who had studied medicine in Edinburgh and Leiden, but abandoned a career as a physician to concentrate on his experiments in chemistry and on agricultural improvements on his farms. His detailed observations of soil being washed from the land and deposited into ditches and river beds, together with his knowledge of the rocks around Edinburgh, led him to the then revolutionary proposal that sedimentary rocks such as mudstone, sandstone and limestone were formed by observable processes of erosion of the land surface and the deposition of the derived material into a lake or sea. The sedimentary layers so produced were consolidated into hard rock by heat, and must then have been uplifted to their present positions on land where they can be observed now. This view contrasted with the prevailing theory, termed Neptunism, which held that all rocks (including crystalline igneous rocks such as granite!) were precipitated from the great biblical flood.

Hutton was familiar with the active volcanoes of Italy, and deduced that the rocks of Salisbury Crags in Edinburgh (Fig. 2.1) were of volcanic origin. He observed how veins of granite and dykes of basalt had penetrated into their host rocks, concluding that they must have been molten, and younger than the host material. He proposed that the interior of the Earth was hot, and that this heat was responsible for the creation of new rock. As these processes were very gradual, he emphasised the great timespans necessary to explain the known geological record, and that in terms of the formation of the Earth, there was ‘no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end’. This, again, was in conflict with the prevailing opinion, based on the contemporary religious orthodoxy, that the Earth was formed in a single event no more than a few thousand years ago.

Hutton’s views were first published in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1788 but did not appear in book form until 1795. It was Hutton, known as the ‘father of modern geology’ who established geology as an independent science. However, although Hutton clearly understood that mountains were composed of a wide variety of rocks whose origins could be explained by sedimentary and igneous processes, he was unable to provide a satisfactory solution to the problem of how the mountains themselves originated.

Hutton had travelled to the Alps, and knew that layers of limestone containing the fossil shells of marine creatures, identical to those found in present-day seas, occurred high up in the Alps and other great mountain chains. He realised that some mechanism was required to elevate them from their original site of formation at the bottom of the sea to their present position. He was also aware of the widespread occurrence of igneous rocks such as granite in mountainous terrains, and knew that great heat was required to melt them. He therefore suggested that ‘subterraneous fire’ – a deep-seated heat source – caused the expansion necessary to elevate the mountains, arguing that if volcanoes such as Etna and Vesuvius could produce sizeable mountains purely as a result of internal heat, then surely the same process could also account for the much greater expansion necessary to explain the Alps. He noted that volcanoes occurred in many places around the margins of the Alps but not within the mountain chain itself, supposing that, if the subterranean heat could not escape via molten lava from volcanoes, it may have provided a powerful mechanism for elevating the chain. He also believed that the intense ‘contortions’ (i.e. folding) of the strata observed in the Alps could be explained as part of the process of uplift of the massif.

Figure 2.1 Salisbury Crags, Edinburgh. Hutton contended that these rocks were formed from a layer* of whinstone (basalt) of volcanic origin, i.e. derived from a magma, that had been injected into the surrounding sediments [*which we would now call a sill]. Shutterstock©christapper.

Charles Lyell (1797–1875)

Hutton’s ideas were popularised in two influential textbooks, Principles of Geology and Elements of Geology by Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875), both of which ran to numerous editions spanning the period 1838 to 1865. Lyell, born of a wealthy Scottish family, and of independent means, was appointed Professor of Geology at University College, London and spent much of his time travelling in North America and Europe observing geological phenomena of all kinds. He was a close friend of Charles Darwin and influenced the latter’s views on evolution. Lyell’s work covered the whole field of geology (the first edition of his ‘Principles’ textbook extended to three volumes) but a major contribution was to make Hutton’s views more accessible to the general scientific community. However, he made no further contribution to Hutton’s ideas on the origin of mountains.

The contracting Earth theory

The idea that mountain chains were the result of the contraction of the outermost shell of the Earth has been attributed to the American scientist James Dwight Dana (1813–1895) but the theory of a contracting Earth was embraced by many other prominent geologists, including Eduard Suess (Suess, 1906) and Sir Archibald Geikie, whose textbook (Geikie, 1882) provides a good example of how the theory was used to explain the structure of mountains.

The basis of the contracting Earth theory was the belief that the Earth was slowly cooling from its originally hot molten state, and that the cooling of the molten interior gave rise to a shrinking of the solid outer shell or ‘crust’–rather like the wrinkled skin of a dried-up apple! The future discovery of radioactive decay, and the consequent realisation that this additional heat source provided an ongoing supply of heat, meant that the cooling Earth theory had to be abandoned, but this was not generally acknowledged until the mid-twentieth century.

Archibald Geikie (1835–1924)

Sir Archibald Geikie was appointed as the first Professor of Geology at the University of Edinburgh in 1871 and subsequently as Director-General of the Geological Survey of Great Britain from 1881 to 1901; his Textbook of Geology (Geikie, 1882) was the standard guide for geology students for many decades. His views on mountain formation can be summed up in the following quotations from the third edition of his book, published in 1893.

… the true mountain ranges of the globe … may be looked on as the crests of the great waves into which the crust of the Earth has been thrown.

And:

These examples [i.e. the Alps, Rockies, etc. (author)] show that the elevation of mountains, like that of continents, has been occasional and sometimes paroxysmal. Long intervals elapsed, when a slow subsidence took place, but at last a period was reached when the descending crust, unable to withstand the accumulated lateral pressure, was forced to find relief by rising into mountain ridges.

And again:

Geologists are now generally agreed that it is mainly to the effects of the secular contraction of our planet that the deformation and dislocation of the terrestrial crust are to be traced. The cool outer shell has sunk down upon the more rapidly contracting hot nucleus and the enormous lateral compression thereby produced has thrown the crust into undulations, and even into the most complicated corrugations.

Harold Jeffreys (1891–1989)

Sir Harold Jeffreys was a Fellow of St. John’s College Cambridge, who published highly influential work on mathematics, geophysics and astronomy. His 1924 work, The Earth, its origin, history and physical constitution became a standard text on geophysics. Jeffreys was a prominent and effective opponent of the theory of continental drift because he believed that there was no known force strong enough to move the continents across the Earth’s surface. His calculations of the strength of the Earth were based on the view that the Earth had cooled from an originally molten state, and that its strength was equivalent to that of the surface rocks. However, work by Sir Arthur Holmes and others in the 1920s on the heat generated by radioactive decay had shown that the interior of the Earth was much warmer than Jeffreys had thought – in fact, as we now know, close to the melting point of rocks at relatively shallow depths of about 50km in places. As rock becomes warmer, it also becomes significantly weaker, thus invalidating Jeffreys’ calculations.

Jeffreys’ views on the origin of mountains are well expressed in the following quotation from his later book, Earthquakes and Mountains, published in 1935.

The elevation of a mountain system represents work done against gravity … At present the strength of the crust is preventing gravity from making the surface level, but when the mountains were formed it was aiding gravity in resisting the stresses that made them. To explain the origin of mountains we must provide sufficient stresses as will overcome both the strength of the Earth and gravity, for in a symmetrical body, both would act together in opposing any change of shape. The only agency that seems capable of supplying such stresses is contraction of the interior … a sinking crust has to acquire a shorter circumference to fit the new size of the interior.

The shortening needed was calculated by Jeffreys using the known crushing strength of granite, and indicated that a section of the crust could be compressed by 1/800th of its length before being crushed, and therefore it followed that the Earth’s circumference of c.40,000km could be shortened by c.50km before failure (e.g. folding or faulting) occurs. From this he estimated that 70km shortening would be required to produce the Alps and 190km for the Himalayas. These figures contrast strikingly with those calculated from the actual structures within these mountain belts, as will be seen later.

From geosynclines to mountains

The concept of the geosyncline was first introduced by the American geologists James Hall and James Dwight Dana in the mid-nineteenth century as a result of their studies of the Appalachian Mountains. The term was used to describe a large elongate basin within the crust that gradually deepened and became filled with sediment. The idea was later elaborated with the recognition of two distinct categories: the ‘eugeosyncline’, which included extensive vulcanicity and sediments typical of the continental slope and deep ocean, and the ‘miogeo-syncline’, which contained sediments more typical of the continental shelf, and which lacked vulcanicity. The geo-synclinal hypothesis of mountain formation supposed that, as the geosyncline filled up, it became unstable and collapsed under the combined influence of gravity and horizontal contraction. It subsequently became elevated to form a mountain chain. These ideas were widely accepted as an explanation for the origin of mountain belts until replaced by the plate-tectonic theory in the 1960s.

J.H.F. Umbgrove (1899–1954)

Umbgrove was a Dutch geologist whose ideas on the formation of mountain belts were strongly influenced by his knowledge of the Indonesian island chain, but he also had views on the origin of the Alps, which are illustrated by a lecture he gave to the Société pour l’avancement des Sciences at Geneva in 1948, and reproduced in a book, rather grandly titled Symphony of the Earth (Umbgrove, 1950).

Umbgrove describes what he imagines would be the result of a gradually deepened and filled geosyncline as follows.

It is not difficult to imagine what must happen during a subsequent period of strong compression of the earth’s crust. The contents of the furrow [i.e. the geosyncline] will become crumpled and folded. Some of the large folds will protrude over the border of the trough and slip onto the adjacent ‘foreland’ … In a more advanced stage the whole zone will tend to rise, for the thick pile of light sedimentary rocks will tend to re-establish equilibrium as soon as it gets the opportunity to do so, just as a submerged log pressed down in water will rise upwards as soon as the force which pressed it down is taken away. Consequently, from the elongated belt emerges a mountain range.

Umbgrove here, in his analogy of the floating log, is referring to what is known as the principle of isostasy. This holds that the Earth’s crust is in a state of general gravitational equilibrium, such that a mass excess at the surface must be compensated by a mass deficiency beneath. Thus a mountain range must be supported beneath by a mass of material less dense than the surrounding lower-crustal rocks, such that the weight of that part of the crust would be equivalent to that of the adjacent borderlands in order to be gravitationally stable. The usual analogy is with an iceberg floating in water, where a large part of the ice is submerged. In the case of Umbgrove’s mountain range, the excess of less dense material depressed into the denser substratum causes a gravitational imbalance that elevates the mountains, restoring them to a state of equilibrium.

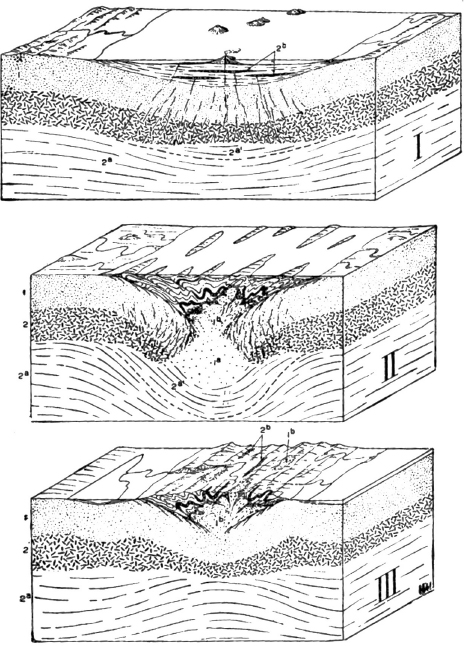

Figure 2.2 Formation of a mountain belt according to Umbgrove. Stage I: sediments accumulate in a gradually subsiding trough (geosyncline); II: under a combination of downward and lateral pressure, the base of the sediment pile collapses, allowing an influx of deep-crustal material (e.g. granite); III: gravitational equilibrium is restored with the elevation of the mountain range. Crustal layers: 1, granitic layer; 1a, granite batholith; 2, ‘basic’ layer; 2a, ‘basic substratum’. © Umbgrove, 1950, with permission.

The sequence of events envisaged by Umbgrove is illustrated in Figure 2.2. At an advanced stage of the depression of the trough (i.e. stage II in the figure), the combination of gravitational and lateral pressure causes the disintegration of the lowest part of the trough, allowing the rise of granitic material from the lower crust. The final stage (III) is when gravitational equilibrium is restored by the uplift of the geosyncline to form the mountain belt.

Continental drift

Continental ‘drift’ was the name given to the concept of the relative movement of the continents around the Earth’s surface, and was the first theory that offered the realistic possibility of explaining the localised contractions responsible for the creation of mountain belts such as the Alps. The contracting Earth theory advanced by geologists such as Suess and Jeffreys had eventually to be abandoned once it was generally accepted that the Earth was continually generating heat from radioactive sources, was not cooling down and therefore not shrinking. The idea of continental drift had been around even before 1912, when Alfred Wegener had proposed it. The American geologist F.B. Taylor had suggested in 1910 that ‘crustal creep’ of the continents could explain the shapes of the Alpine–Himalayan mountain chain – notably the convergence of India and Australia with Asia. However, the lack of an adequate mechanism for the movements, and of any convincing geological evidence in support of his ideas, meant that they received little recognition in comparison with Wegener’s.

The reasons why continental drift took such a long time to be accepted as a valid hypothesis by the scientific community as a whole offer an interesting insight into the background and personalities of some of the key individuals in a debate that lasted for over forty years.

Alfred Wegener (1880–1930)

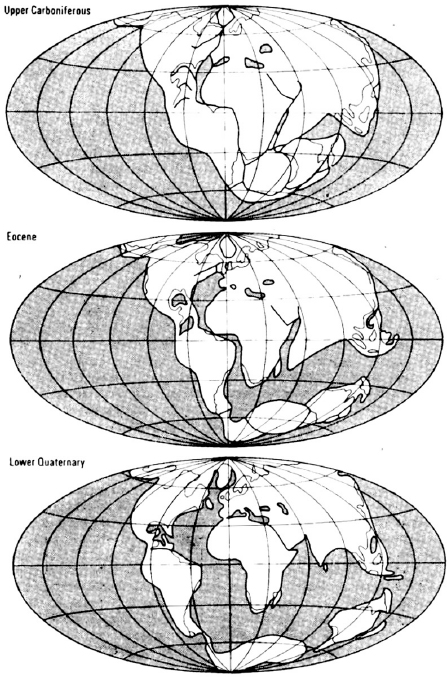

The theory of continental drift is usually attributed to Alfred Wegener, a distinguished German meteorologist who had undertaken four expeditions to Greenland to undertake meteorological investigations, during the last of which he tragically lost his life while undertaking a traverse of the icecap. He published his views on continental drift (in German) in 1912 in the scientific journal Geologische Rundschau and again in book form in 1922 (Wegener, 1922), to explain the numerous geometric and geological similarities between continents that are now separated by oceans. The continents of South America, Africa, India, Australia and Antarctica were shown to fit together in a supercontinent called Gondwanaland (originally named by Eduard Suess; now usually ‘Gondwana’), and North America and Eurasia into a second super-continent called Laurasia (Fig. 2.3). These two super-continents were joined in Central America to form a continuous worldwide landmass termed Pangaea (pronounced ‘Pan-jee-a’).

Figure 2.3 Wegener’s reconstruction of the continents from the Carboniferous to the Quaternary. From Du Toit, 1937.

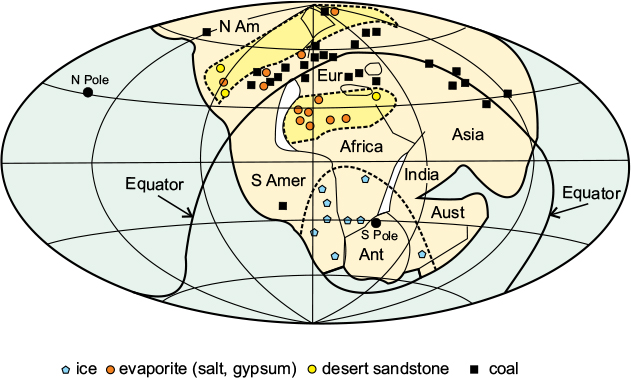

When this continental reconstruction was examined, many geological features shared by the separated continents could be explained. These include the presence of glacier-derived clays and glacial striations, which in their present positions cover about half the globe, but when restored to their presumed Gondwana fit, make a reasonably-sized polar ice cap. The distribution of other climatic indicators in rocks 200 million years old also makes sense when in the Gondwana fit; these include dune-bedded sandstones and salt deposits, which mark out two desert belts on either side of a central equatorial belt indicated by the presence of coal deposits and coral reefs suggestive of tropical conditions (Fig. 2.4). There are also similarities between many fossil land animals and plants that existed 200 million years ago in the different continents prior to the splitting up of the supercontinent, and this contrasts with the obvious differences that exist between the fauna and flora of the separate continents now. However, much of the detailed geological observation to support these ideas was undertaken later, by Alexander Du Toit.

Figure 2.4 Gondwanaland in the Carboniferous. Climatic belts according to Wegener. Note: 1, the band of coal deposits parallel to the Carboniferous Equator (heavy black line); 2, desert areas (in yellow) marked by desert sandstones and evaporite deposits on either side of the equatorial belt; 3, large polar area showing evidence of glaciation. After Wegener, 1922.

Wegener believed that mountain belts such as the Alps and Himalayas could be explained by the effect of two continents converging during the amalgamation of Pangaea – Africa with Europe in the case of the Alps, and India with Asia, in respect of the Himalayas. The oceanic area partly enclosed by the super-continent was named the ‘Tethys Ocean’ by Eduard Suess (see above), who believed that the present-day Mediterranean Sea was a remnant of this former ocean, and that much of the former ocean-floor had been incorporated into the Alpine mountain belt during its formation. The circum-Pacific belt, which includes the American Cordilleran Chain and the Andes, was more difficult to explain by collision, since it required the Pacific Ocean crust to be strong enough to buckle the edge of the American continent, which would contradict Wegener’s model of a weak ocean crust. Wegener had suggested that the continents were able to move from their original positions in Gondwana and Laurasia to their present ones because the oceanic crust was much weaker than the continents, which could somehow plough their way across it.

Wegener’s lack of geological background and inability to provide sufficient ‘geological’ evidence to support his theory meant that his ideas received very little support, especially in the northern hemisphere, partly because they were initially published (in German) during the First World War. Wegener’s book was not published in English until 1966. His views were communicated to a wider audience via a lecture he gave in New York in 1926, but were widely criticised. Many geologists, and particularly geophysicists, were influenced by Sir Harold Jeffreys’ calculations of the strength of the Earth’s crust, which we have already referred to, and opposed continental drift because they believed that the Earth’s crust was too strong to allow the kind of behaviour that Wegener’s theory required.

Wegener’s ideas caused considerable debate among the geological community, but failed to obtain universal acceptance, mainly because of the lack of a convincing mechanism for the movements. It was not until the 1950s that advances in palaeo-magnetism produced enough evidence to convince geologists that the theory was correct.

Alexander du Toit (1878–1948)

Du Toit was a South African geologist who had studied mining in London and taught geology at Glasgow University in the early years of the twentieth century, but returned to South Africa and spent many years travelling extensively in southern Africa, South America and Australia gathering the detailed field evidence required to support the geological comparisons necessary to bolster the continental drift theory. In 1927, he published his studies comparing the geology of southern Africa with that of South America, and ten years later (Du Toit, 1937) his comprehensive work Our Wandering Continents, An Hypothesis of Continental Drifting, which gave much of the detailed evidence necessary to establish continental drift as a valid theory, to be taken seriously by a large proportion of the geological community.

In addition to providing many further examples of geological matches across the now severed edges of the southern continents, he was able to demonstrate much more convincing evidence for various climatic indicators in rocks of Carboniferous age in the southern Gondwana continents. He pointed out that the distribution of these climatic indicator rocks makes no sense in their present locations; for example, coals representing the product of equatorial forests now lie near the North Pole, and glacial deposits lie near the Equator!

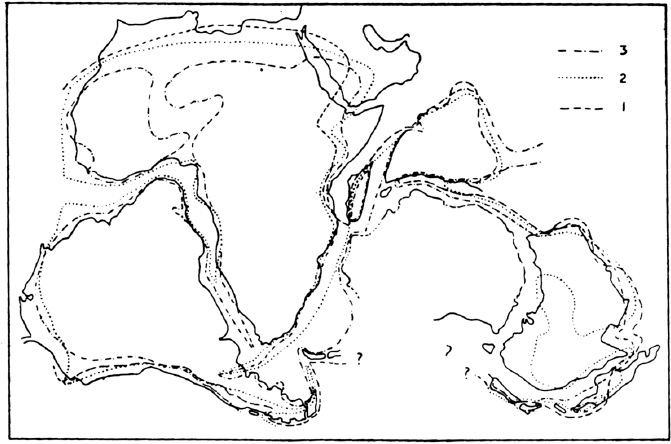

It should be noted that the term ‘continent’ used in a geological sense includes, in addition to the landmass, areas of the adjacent sea bed – the continental shelf and continental slope – that are underlain by crust of continental, rather than oceanic, type. Du Toit showed that when the shape of the continents is adjusted to include these, a much better fit of the Gondwana continents is achieved (Fig. 2.5). His reconstruction of the pre-drift continents differed from Wegener’s in that the northern grouping, Laurasia, was centred around the then North Pole and was separated from Gondwana by a wider Tethys Ocean.

Du Toit proved that much of the process of separation of the Gondwana continents must have taken place during the Mesozoic Era, whereas Wegener had thought that most of the movements had occurred in the Tertiary (Cenozoic) and continued into the Quaternary Period (i.e. the last 2.5Ma) as well. He also extended the drift mechanism to explain the older Paleozoic mountain belts such as the Caledonian belt, now severed by the Atlantic Ocean.

A warmer Earth – convection

Arthur Holmes (1890–1965)

Holmes pioneered the use of radioactivity in dating rocks, and published the first date using the uranium-lead method in 1911 shortly after graduating from Imperial College, London, where he continued to work on the subject, publishing The Age of the Earth in 1913, in which he estimated a date of 1600 million (1.6Ga) years for the oldest rocks then known. By the 1940s this date had been revised upwards to 4500+/-100Ma, approximately equivalent to the presently accepted date. In 1943 he was appointed Professor of Geology at Edinburgh University, where he remained until retirement. His Principles of Physical Geology (Holmes, 1944) was the standard textbook on the subject for many decades; the fourth edition, edited by P. McL. D. Duff, published in 1993, is still in use.

Holmes’ work on radioactivity enabled him to demonstrate that the Earth must be much hotter than previous estimates, which had been based on the cooling Earth model. It must, therefore, also be much weaker than previously thought, and he suggested that the mantle could be capable of transferring heat from the interior to the surface by slow flow in the solid state. He visualised a system of convection currents (Fig. 2.6), the upper parts of which could carry continents across the Earth’s surface. As well as providing the missing mechanism for continental drift, this idea was a major contributory factor in the development of the plate-tectonic theory, discussed in the following chapter.

Figure 2.5 Gondwanaland according to Du Toit. Note that this reconstruction includes the continental shelves and is a much more accurate representation of the coastlines than Wegener’s. The dotted and dashed lines represent the positions of the shorelines during (1) early Jurassic, (2) early Cretaceous and (3) late Cretaceous time. From Du Toit, 1937.

Figure 2.6 Arthur Holmes’ interpretation of continental drift. From Holmes, 1929.

Palaeomagnetism

The debate on continental drift carried on until the 1950s, when work on palaeomagnetism (the study of the magnetism of old rocks) finally convinced most geoscientists that the continental drift theory was correct. The science of palaeomagnetism depends on the fact that certain rocks (e.g. basalts and iron-rich sandstones) acquire weak magnetisation from the contemporary geomagnetic field and behave as a kind of magnet. A sensitive magnetometer can measure this geomagnetic field to determine both the direction of magnetic north and the latitude of the magnetic field. This magnetic information is ‘stored’ within the rock, and unless it is disturbed by some subsequent event such as metamorphism, it will represent a ‘fossil’ magnetic field at the time when the rock was originally formed.

Work by a group of geophysicists at Cambridge University in the later 1950s obtained revolutionary results indicating that the apparent pole positions of rocks with ages varying from Jurassic to Quaternary showed widely different positions that formed a ‘polar-wander curve’ or track ending at the present pole. Moreover, the tracks for each continent were different, proving either that the Earth’s magnetic field had behaved in a very strange and inexplicable way over the last 200 million years, or that the continents had indeed changed their relative positions with time. The Cambridge group included S.K. Runcorn, who subsequently headed the Geophysics Department at Newcastle University, and while there, summarised the results in a landmark paper published in a volume entitled Continental Drift (Runcorn, 1962).

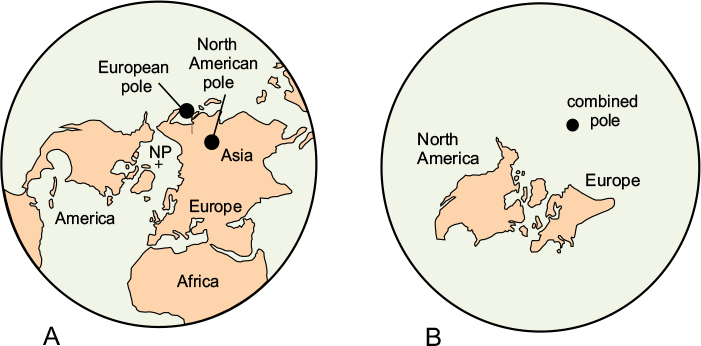

Runcorn showed that, for example, the positions of magnetic north for 200 million-year-old rocks in different continents plotted in different places (Fig. 2.7A). However, when the continents were fitted together in their presumed original positions according to continental drift theory, the locations of the magnetic north poles coincided (Fig. 2.7B). This was convincing proof that the continental drift theory was in essence correct, and because the evidence was supported by respected geophysicists, managed to convert most of the doubters of the geological fraternity.

Figure 2.7 Palaeomagnetic evidence for continental drift. A. North Pole positions for Europe and Africa in 200Ma old rocks. B. Position of combined pole when continents are moved into their pre-drift positions. After McElhinny, 1973.

Topography of the ocean floor

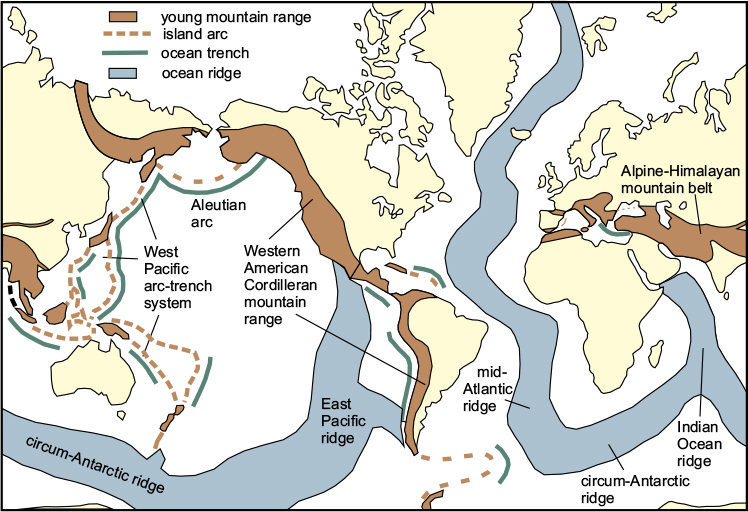

The next stage in the evolution of ideas came from studies of the ocean floor, where mapping by various remote-sensing techniques had revealed a topography that was as varied as that of the continents. The generally even ocean floor is interrupted by a system of great ridges and deep, narrow trenches (Fig. 2.8). The ridges are typically between 1000 and 2000 kilometres wide and rise to as much as 3 kilometres from the ocean floor. They form a continuous network, one branch of which runs from the Arctic along the centre of the Atlantic Ocean (the Mid-Atlantic Ridge) to join a second branch that completely surrounds Antarctica and crosses the Pacific Ocean towards the coast of Mexico, sending two branches into the Indian Ocean. The trenches are much narrower (typically around 100 kilometres wide) but extend to depths of up to 11 kilometres below sea level. They form generally curved linear features on the ocean-ward side of island chains around the western Pacific Ocean, the eastern Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, and along the Pacific coast of America. Much of this information had been available even in Wegener’s time, but its significance was not understood until the sea-floor spreading idea at last gave a believable explanation. Extensive work by American oceanographers based at Scripps Institute in California and Lamont-Docherty at Columbia University, New York, produced a greatly expanded knowledge of the topographic detail of the ridge–trench system, which will be described in detail in chapter 13.

H.H. Hess (1906–1969)

The breakthrough in understanding that finally solved the problem of a mechanism for plate movements came from H.H. Hess of Princeton University, who proposed that the ridges were underlain by hot, rising mantle currents and the deep-ocean trenches by cool, descending currents; this he called ‘sea-floor spreading’. First published in a Report of the (US) Office of Naval Research in 1960, his theory was explained in detail in 1962 (Hess, 1962), and is also explained in the chapter by R.S. Dietz in Runcorn’s book on Continental Drift (Runcorn, 1962). Much of the objection to Wegener’s ideas on continental drift had centred on the failure to visualise how a continent could plough across a static ocean crust. However, this objection was countered by Hess’s proposal that the ocean crust itself was mobile, and behaved like a giant conveyor belt, rising at the ridges and moving sideways towards the deep-ocean trenches, where it descended (Fig. 2.9). In other words, both continents and oceans were mobile rather than static.

Figure 2.8 Principal topographic features of the Earth. Note the size of the ocean ridges compared with the continental mountain belts and the narrow ocean trenches. After Wyllie, 1976.

Figure 2.9 Sea-floor spreading. New ocean crust is created at ocean ridges and destroyed at ocean trenches by flow within the mantle.

Dating of the ocean floor

Wegener and Du Toit had thought that the ocean ridges marked the lines of separation of the continents, and consisted of foundered continental crust (see Fig. 2.4), but the paleomagnetic dating of the ocean floor of the Atlantic and Indian oceans in the 1960s showed that the ridges were the most recently formed parts, and that the ocean floor became older towards the continental margins. This work proved that the continents of Gondwana and Laurasia had indeed moved apart, and that the space between had been filled by new ocean crust.

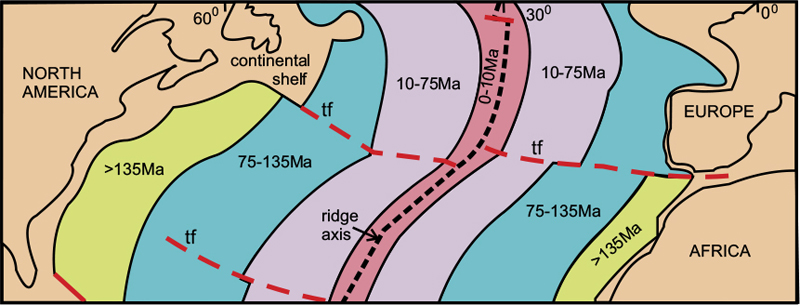

The dating of the ocean crust relies on the fact that new crust forming along the ocean ridges becomes imprinted with the contemporary magnetic field; this changes periodically because the Earth’s magnetic field reverses at irregular intervals, each of several hundred thousand to several million years long, after which the magnetic north and south poles are swapped. Each of these intervals creates a long strip of crust, parallel to the ridge axis, whose magnetic character differs from the previous one, and can be distinguished from it by remote measurement with a magnetometer. As new strips are created, older strips move away from the ridge axis. This process creates a series of magnetic bands or ‘stripes’ on the ocean floor, each of which represents a particular period of formation (Fig. 2.10). The stripe sequence was dated by comparing it with sequences of lava flows on land whose dates were known.

Figure 2.10 Oceanic magnetic stripe pattern. Three idealised cross-sections of ocean crust showing how stripes of alternating magnetic polarity are created every time there is a change from normal to reverse polarity: A, 3.4–2.5Ma ago; B, 2.5–0.75Ma; C, 0.75–Present.

The age pattern of the Atlantic ocean floor given by palaeomagnetic measurements (Fig. 2.11) indicates a simple pattern where the youngest dates (0–10Ma) are in a central strip (red) along the axis of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, proving that the ridge was the site of formation of new ocean crust at the present day. On each side of this central strip are successively older bands, with the oldest (>135Ma) adjacent to the North American and African coasts respectively. These dates thus correspond to the dates when these continents originally separated. Note that north of the fault separating Africa from Europe, the oldest dates are younger (75–135Ma) indicating that Europe separated from North America at a later date. (This fault is a transform fault, as explained in the following chapter.)

Figure 2.11 Dating the ocean floor. The age pattern of the Atlantic Ocean floor given by palaeomagnetic measurements indicates a simple pattern where the youngest dates (0–10Ma) are in a central strip (red) along the axis of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. On each side of this central strip are successively older bands with the oldest (>135Ma) adjacent to the North American and African coasts respectively. These dates correspond to the dates when these continents originally separated. Note that north of the transform fault, the oldest dates are younger (75–135Ma) indicating that Europe separated from North America at a later date. tf, transform fault. After Larson & Pitman, 1972.

Ocean crust could not be continuously created without it being destroyed elsewhere (unless the Earth was expanding), and the obvious sites for its destruction were the deep-ocean trenches as proposed by Hess. The new palaeomagnetic dating evidence demonstrated that the ocean crust adjacent to the trenches showed a variety of ages (i.e. a ‘discordant’ age pattern) whereas the crust adjacent to continental margins that had moved apart showed a ‘concordant’ age pattern, as in Figure 2.10B, in which the oldest age was consistent with the date of separation of the continent. This evidence confirmed that the conveyor belt model for the ocean floor was essentially correct.

Now, thanks to the innovative genius of Alfred Wegener, Arthur Holmes and Harry Hess, married to the detailed and exhaustive field observations of Du Toit and the laboratory work of the geophysicists, all the preconditions for the plate-tectonic theory are in place.