Five days after we had taken over from 2 RAR we were out on a shakedown operation. I didn’t enjoy this trip into the bush very much as I had a bout of dysentry. Almost everyone had had the ‘Nui Dat runs’ after a couple of days in the country, but mine came when I least wanted it. We were inserted into an area about five or six kms south-west of Nui Dat to get a feel for the bush. The area we worked in was old rice paddy fields with occasional clumps of bamboo. This bamboo was unlike anything I had seen before. It was mainly brown but instead of leafy stalks it had thorns like six-inch nails over the whole plant and was impossible to move through. The bamboo branches were incredibly tough and tanks found it difficult to penetrate them.

We married up with a troop of APCs and got a taste of what working in a sauna was like. My recollections of all this were pretty vague as I spent most of my time on my back, weak from the dysentry. One of the more impressive things on this operation was a troop of Centurion tanks from C Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment, who gave us a demonstration of what canister ammunition from the tank main gun will do. The round is a muzzle detonating, 20 pound, 84 mm, version of a shotgun. The canister round projects hundreds of steel rods about an inch long and the effect on jungle is devastating. The troop fired together into a patch of jungle and literally defoliated the bush. What had been difficult to see through was now left bare.

Apart from the canister demonstration we saw little else apart from a freshwater crocodile and a few deer. The area had not had any enemy activity for some time and considering the fact that I spent a lot of this short operation with my trousers around my ankles, I wasn’t too upset at the lack of action.

We only carried two days’ rations on this operation but it was like carrying a full load back home in Australia. The difference was that we were carrying live ammunition. Everyone had at least five magazines of small arms (ten if you were carrying an Armalite (M16) rifle) plus a couple of grenades, a claymore mine and the odd smoke grenade. In addition each section was carrying extra ammunition for the machine gun and that totalled about 800–900 rounds per gun. The heat and humidity combined with the weight we were carrying, ensured our shirts stayed wet from sweat the moment we jumped off the choppers until we climbed back on two days later to go back to Nui Dat. Back in Australia on exercise we would have got smelly from the sweat only after about five days of patrolling. I noticed when we were on the helicopters on the way back from this operation that we stank terribly after only two days.

When we returned from this operation, D Company was put on ‘ready reaction’ duty. This meant we had to be fully booted and spurred and ready to go at a moment’s notice. The 1st Battalion of 274 Viet Cong (VC) Main Force Regiment, which was about 180 strong, had been identified as being back in the province. Our Kiwi company, Victor Company, was out in the area of operations looking for them; we were standing by to assist. Each platoon had a different degree of notice to move, varying from fifteen minutes to half an hour. Kev Byrne’s platoon was on the shortest notice. He had to be briefed at the battalion command post, give quick deployment orders and be down at the chopper pad. We timed this platoon on what turned out to be a practice run and the lads took thirteen minutes. This made our company commander quite happy.

That night we were allowed to have more than the normal ration of beer, which was two thirteen-ounce cans per day. Often described as ‘two cans per day perhaps’, it was well received as our company was the only one where all ranks had been limited to two cans when they were off duty. The beer we drank was Australian. It came in and was ordered by its colour: blue for Fosters, green for Victoria Bitter, yellow for Castlemaine Fourex and white for Carlton. I found that after my bout of dysentry I had lost my appetite for the extremely rich American rations we were getting and for any great quantity of beer. I switched to Bacardi rum which was still cheap as we only paid $1.40 for a 40-ounce bottle. Coca Cola was still the dearest thing one could drink.

‘Murphy’s Law’ prevailed the first night we had more than two beers available to us. That night the Task Force had stand to emergency drill and we had to get into our fighting gear and man the base defences. Each platoon had several machine-gun bunkers, which were always manned by the duty company, and also rifle pits, flanking the gun pits. There was a central platoon headquarter bunker where we had our claymore mine firing devices hooked up and a telephone to the three machine-gun bunkers and to the company command post. Each bunker carried spare ammunition for the section, grenades and flares. By the time the stand to drill was over, it was after 2200 hours and time for lights out. So much for a night on the beer.

It was at this time that I noticed that Peter Schuman looked really off-colour; he was being worked fairly hard by the company commander. When he walked in for dinner one night he was not a pretty sight. He wasn’t the only one to change appearance. A lot of us had begun to grow moustaches (to aid facial camouflage) and had lost a little weight. I had lost seven pounds in only two weeks. I was looking around for some padding to put on the inside of my webbing belt to stop it rubbing the skin off my hips.

The first real operation the company deployed on was called Bhowani Junction. We went through all the normal battle procedure just like it was an exercise with test firing weapons, kit checks and patrol orders to the diggers. We weren’t to have a spectacular helicopter insertion for this operation as we were going in by truck. The operation was designed to clear an area around where the battalion was going to establish a fire support base. I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but this initial deployment was a prelude to a very large operation involving about a brigade’s worth of men. We had been warned not to talk about the operation to anyone outside the company as security was vital to its success. There were quite a few Vietnamese locals who worked inside the Australian Task Force base and who were supposedly security cleared. The Vietnamese worked as labourers around the base, keeping the place clean and the vegetation under control. Quite a few others worked in the PX, general store and barber shop. However, 3 RAR had had a contact with a patrol in the southern part of the province and one of the enemy killed was later identified as one of the barbers who worked in the Australian Logistic Support Group base at Vung Tau.

We got quite a shock when the trucks turned up to take us out on our first large-scale operation. These vehicles only had side seating. Any road movement which we had ever practised on exercise was always on trucks with centre seating so that everyone was facing out and could fire his weapon without endangering his own troops. In the case of vehicle ambush it was essential to have centre seating to be able to return fire, and also be able to get out and onto the ground and find cover. When I asked the Royal Australian Army Service Corps drivers to fix up the centre seating I was told they couldn’t because the trucks were needed for a cargo task straight after our insertion. Besides they didn’t have all the necessary pins and most of the seats were rusted in anyway! After all the insistence on doing everything by the book, of always watching your arse and never letting your guard down, all I could think was that these guys were just typical ‘pogos’ (Personnel On Garrison Operations—or base camp types), who didn’t give a damn about the infantry on the back of their precious bloody trucks. I was not amused at all.

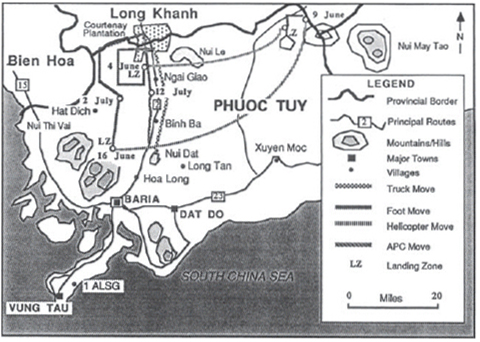

We left the Task Force base with our side-seated trucks but I posted extra men to watch our flanks and had a soldier with a grenade launcher sit right at the rear of the truck with a high explosive grenade up the barrel just in case. Our destination was an area near the Courtney rubber plantation to the west of the main north-south road in Phuoc Tuy Province, called Route 2. As we drove up the road we saw the countryside at close quarters for the first time. Our shakedown operation had been away from villages and hamlets but now we were driving right past and in some cases through them.

The peasant villages were best described as hovels with livestock sharing the same quarters as the occupants and no sanitation to speak of. Their smell was quite strong and far from pleasant. It was noticeable that men were not doing too many jobs and the only male I saw working was driving a buffalo-drawn plough in a rice field. As we passed through a village called Ap Ngai Giao (pronounced ‘ny jow’) I saw a man in black ‘pyjama’ dress with the trouser leg rolled up to his crotch, apparently urinating on the wall of a hut. Every village our convoy passed through had children between two and twelve years waving and holding up their hands in the ‘V’ sign and yelling for cigarettes or sweets. One of the diggers threw a ration can of luncheon meat to a youngster who immediately recognised this almost inedible gastronomic disaster. The kid hurled the can back in our general direction with a single digit salute screaming, ‘Number fucking ten, Cheap Charlie!’

By the time we arrived close to the province border, we had had our eyes opened on several counts—including how slack the Regional Force and Popular Force soldiers appeared in their posts as we drove past. No-one seemed alert and the state of the various field defences was quite shoddy Once the platoon was off the side of the road we moved into the bush about two or three hundred metres and I signalled for a quick halt. I wanted to make sure exactly where I was before we started and to ensure I had good communications with the company before we set off.

This operation would be fairly typical of those we would go on. The platoons were given areas to clear and worked independently of company headquarters. Every hour I would send in an encoded location state (locstat) telling company headquarters and the other two platoons in the company where I was and in what direction I was heading. If I was stationary for any length of time I would make sure people knew where my platoon was and would do a radio check to make sure no-one was trying to reach us on the set.

On this operation I had been given several 1000 metre grid squares of the map to search and clear. The jungle wasn’t too bad and a lot of my area was rubber plantation. We started patrolling in single file through the bush and we were moving at about one kilometre per hour. This was considered to be a good patrol pace for the jungle as we could move fairly quietly and therefore maintain our security. Any faster meant that the soldiers were not too worried about where they were putting their feet and not worrying about searching their arcs of vision. It also became apparent that any faster meant we became tired quicker and our alertness suffered.

The platoon patrolled uneventfully for the remainder of the day: we had searched a couple of grid squares without finding any sign of the enemy. Because last light was around 1800 hours I wanted to be in a ‘harbour’, or defensive position, for the night by about 1700 hours. I didn’t like the idea of harbouring and eating in the same location, as cooking smells hung in the jungle air and I didn’t want someone hitting us with a nasty surprise like an ambush or mortar attack. So we had to cease patrolling around 1600 hours to let everyone eat, clean weapons and so on.

Once our administration was out of the way we patrolled on for another 500 metres or so then broke off our track into the scrub for 100 metres and patrolled for another 100 metres. Using our direction of travel as a start point we then harboured in a circle ensuring we had a machine-gun covering the track we had come in on. Once the platoon was down on the ground, and all the sections had linked and the perimeter was complete, we stood to while a small half-section patrol quietly circled outside the perimeter to make sure there were no signs of the enemy. Once this clearing patrol was back inside the perimeter we posted sentries in front of each gun to give early warning if the enemy were approaching. While this was being done the section commanders set up the claymore mines on any approaches to our position or if none, as was usually the case, in an arc to their front. We had devised a system whereby we could fire our claymores in banks of three or six. For harbours in thick jungle I opted for claymores in groups of three as it gave more flexibility in firing and we could cover more areas. The section second-in-commands meanwhile were busy drawing up a gun picquet for the night in the sections.

Each section machine-gun would be manned continuously throughout the night by a staggered picquet. There would always be a fresh man on the gun and less likelihood of a gun picquet falling asleep. My job was to coordinate with my mortar-fire controller on what indirect fire tasks I would like to register for the evening. This was usually a simple task; but if there were no tracks in the area we picked likely enemy navigation check points—such as vegetation changes, for instance from rubber to jungle, as targets.

My mortar-fire controller was a most experienced man. Ziggie Sinclair had been a mortar-fire controller for years and knew the job backwards. Generally I would simply ask him to select some likely looking targets. He usually came up with what I would have selected anyway, and after my agreement he would register the targets. There was no actual firing onto these targets; they were ‘silently registered’ and would have to be adjusted if they were actually fired. With eight men in a section, most men would do about a two and a half hour picquet, and after a day carrying a 70 pound pack on your back in 90 degree heat it was easy to drop off at night. One of the great incentives for not falling asleep on picquet was the threat that if charged with such an offence you would not only have lost the trust of your mates but also the commanding officer would hear the charge—and on war service the punishment for this was pretty severe. Just as the guns had to be manned at night, so the radio and the platoon headquarters had to keep a set open throughout the night and answer radio checks from the company.

The operation turned out to be a single picquet: we didn’t have enough men to do a double, and I didn’t like the radio to be manned by the same gun picquet who was supposed to be watching and listening to his front. Our first night passed quietly and at first light we broke harbour in virtually the reverse order that we had occupied it the night before. We moved about 500 metres in the direction I had planned to go the next day and stopped to have breakfast, to clean weapons and issue orders for the day’s patrolling. In planning a day’s patrol I had to keep in mind where other patrols would be and where I believed the enemy could be positioned. The chances of finding the enemy in jungle are usually fairly remote as the vegetation is often so thick you can walk within ten metres of someone and not see them. Consequently I often opted for a systematic search of a grid square of jungle based on scribing a box on the ground and hoping to cross an enemy track along our route.

After we moved out of our administration harbour, the patrol pattern took the form of moving for about 50 minutes, stopping to send a locstat, a brief rest and again moving for 50 minutes. Each time we halted for more than five minutes we would do a simple halt drill where the lead section fanned out and covered from 10 to 2 o’clock, the next section in the platoon covered from 10 to 6 o’clock and the tail section covered from 6 to 2 o’clock. There was always a machine gun at 2, 6, and 10 o’clock, with a sentry about 25 metres out. We did this drill almost every time we stopped to give a locstat. There was no requirement for a single word to be spoken to get the platoon down on the ground. All I had to do was give our platoon field signal for a quick harbour and the lads would be down on the ground in a couple of minutes flat—not a word said. It was a good feeling when the platoon could go through drills so quietly and efficiently.

The area we operated in was devoid of any enemy sign. This in itself was not so bad as it was still good intelligence to us; the enemy must be operating somewhere else. Unfortunately this slant on a lack of enemy was not so easy to convey to the platoon, who wanted something more tangible for their efforts. What we did find later in the day was a small cache containing about five kilograms of rice and some small arms ammunition.

Compared to some of the huge caches of previous Australian Task Force operations, this was pretty small stuff. But the platoon was patrolling quite well and everyone was doing his job as best he could. We were still novices in reading sign left by the enemy and the patrol was frequently punctuated by halts to check out something that someone had spotted. Often it was the forward scout who would notice something. He’d call me forward to point out what he had seen. If it was obviously too old to worry about I had to be careful how I handled it, as I didn’t want my scouts to stop reporting in the belief that I would get upset at being called forward all the time.

By the third day of the patrol the area had been fairly well cleared. None of the platoons in D Company had seen anything in our area of operations. A long cryptographic message then came over the radio with orders for us to redeploy for a very large operation, one called Overlord.

Intelligence had found that two enemy units, namely 3rd Battalion, 33 North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Regiment and D445 Local Force Battalion (Viet Cong) were somewhere in the northeast of Phuoc Tuy Province. With the 3rd Brigade, 1st US Cavalry Division (Air Mobile), the 1st Australian Task Force was going to try to search for and destroy the enemy and his bases. The operation would involve thousands of men, aircraft and vehicles. The plan was to form a cordon surrounding the area where Special Air Service patrols had located the enemy and push one end of the cordon toward the other like a plunger in a pump. The success of the operation depended on the cordon being linked up rapidly in the jungle. We were to be inserted by air, as were most of the other companies. Once we were in position 3 RAR and C Squadron tanks would sweep toward us and hopefully push the enemy into our cordon. Our cordon positions were in fact a series of linear platoon ambushes on the likely escape routes out of the area.

The company regrouped. It moved to a designated pick-up zone for the helicopters and made ready to be lifted some 20 km across to the other side of the province. The choppers arrived on time, but they came from a different direction and totalled a different number from what we expected. The pad was chaotic. I had been designated last platoon out of the company pick-up zone and I was to be the pad master. My job was to make sure that people were lined up in the right places to get on the aircraft. So when I was told that there would be six choppers coming from the north I arranged the ‘sticks’ of men into what I thought would be a reasonable formation. All this turned sour when nine helicopters appeared over the top of the trees without warning and plonked down nowhere near where I had sited the different helicopter loads.

Eventually we filled up all of the US Army choppers. They were driven by young American warrant officers about 20–23 years of age. Often the co-pilot was a sergeant or equivalent and about the same age. All of the crew doors, where the pilots sat, were painted with a black ace of spades on a white background. All of the door gunners who manned twin M60 machine-guns on the side of the helicopters were black Americans. The crew all had individually painted helmets with everything from peace symbols to stars and stripes to obscene graffiti all over them. I wasn’t enthused by their ‘gung-ho’ attitude and general air of indifference. They seemed ‘laid back’ and casual and it made me feel a little uneasy as I wondered what their reactions would be when things got sticky.

There was a remarkable difference in flying US air as opposed to RAAF air. The RAAF had officer pilots and the aircraft looked reasonably serviceable. The choppers we clambered into looked tatty and well worn. There were no seats and we sat on the floor of the Iroquois linking our arms together and praying we wouldn’t slide out where there was normally a door.

The time given to boarding was minimal and we were expected to haul ourselves and our 70 pound packs aboard by the time the skids of the chopper had settled. In five seconds the aircraft was in a nose-down, tail-up attitude and beating its way off the pad. The door gunners assisted by grabbing us by the harness of our webbing and heaving us into the chopper, like stevedores moving bales of wool. Once aboard we flew in a direct line to the landing zone but right down at tree level. This tactic was designed to nullify the enemy’s ground fire directed at aircraft and it may well have, but I couldn’t for the life of me read a map as we bucked and veered over and around trees. I wasn’t given a headset to talk to the crew and so I didn’t know if we were being dropped at the right landing zone or what the tactical situation would be once we got off the helicopter.

I tried to attract the attention of the door gunner next to my side of the chopper but he couldn’t hear me yelling at him underneath his iridescent striped helmet. I wasn’t game to reach across and grab him as it would have meant letting go of someone on the floor: the way we were twisting and turning I might have been asking for a quick exit. After 20 minutes or so we slowed to make our descent onto the landing zone.

There were helicopters going everywhere. The sky seemed full of them. We passed about 30 going in the opposite direction and as we started to land I noticed six Cobra helicopter gunships circling above our landing zone. Just as we were about 50 feet off the ground, the door gunners on the choppers started blazing away at the jungle on the edge of the landing zone. This was lovely as nobody had told me the pad was ‘hot’ and that we would have to fight our way off the landing zone. The skids of the helicopter touched down and the door gunners started screaming at us: ‘Get your mother-fucking asses outa there’, hauling us off with the same care they had taken when hauling us on board. The time taken to get out seemed even shorter than getting aboard. I noticed some slower guys were jumping about five or six feet onto the ground as the choppers hurried to get off the landing zone.

On the somewhat quieter ground I listened for the sounds of gunfire but there were none. The pad wasn’t hot at all. It appeared as if our American friends were simply shooting up the bush to impress us or have a go at us. I was not amused by this as it smacked of a cowboy attitude and lacked professionalism. We moved quickly out of the open landing zone into the cover and shade of the jungle beside the pad. I had my radio operator, Paul Howkins, send the codeword that we were safe on the ground and then I gave the order to move out to our designated blocking position in the cordon. I was somewhat relieved that the landing zone wasn’t hot as it would have taken some time to gather the platoon properly to organise a decent reaction to that kind of situation.

The platoon moved to the designated grid reference we had been given in my orders. We passed 10 and 12 platoon who had arrived before us and who were setting up their own positions. Once we had arrived at where I thought we ought to be, I realised we were going to have problems. I didn’t have a definite link with the other platoons, and the bush was so thick I didn’t really have any fields of fire on which to establish an ambush. I rang up the company commander on the radio and asked if we could move closer to 12 platoon. This was refused. I was told to stay where I was and do the best I could. So we set about establishing a linear ambush position from where we could cover the jungle to our front, and about 35–40 metres back I set up a rear area where we could rest and carry out administration. It looked as if we were going to be in this position for some time so we had to make ourselves fairly secure. I sighted the machine guns on the limited fields of fire that we had, and I also had the section commanders set up our claymores in banks of six. I didn’t really know what to expect but if there were a lot of enemy in the area I didn’t want to get overrun.

Nothing happened in our area until the second night. Then we heard that 3 RAR had hit a large part of the enemy as they started to push from the north-west towards us. A situation report indicated that we had hit the 3rd Battalion, 33 NVA Regiment, which having decided to flee and fight again another day, started to withdraw before the 3 RAR and C Squadron tanks could hold them in location and destroy them. The limited action we saw was around 10.00 pm on the second night when we detected movement to our front. The dense canopy of the jungle let very little light through and you could hardly see your hand in front of your face. The platoon was stood to and we waited to see who was going to walk into our ambush. For over half an hour I was up forward, next to my main killing group in the ambush and desperately trying to detect movement. We could hear movement in the bush but it was impossible to tell exactly where it was. I was lying on the ground next to one of my machine gunners, Ralph Niblett, and we both tried to figure out how best we could hit who ever was out there in front of us.

Rather than give away our position by firing wildly into the darkness, I decided to fire a mortar target to our front and walk it in towards us to stir up whoever was out there. All this succeeded in doing was closing the enemy right up to us. From the increased movement we heard, I believed that the Viet Cong were now inside our claymore mines. This was the wrong side for us. We could do very little in that situation but give the enemy a headache. I crawled quietly back to Ralph Niblett and tried to come up with a plan of action. Ralph turned to me and asked in a whispered voice if I could smell anything. I could. It was the same smell I had noticed when we were travelling through the villages several days before. What we could smell was the enemy. I told him to put a twenty round burst where I thought I had last heard movement. Ralph opened fire and straight away there were increased movements and voices.

The enemy started withdrawing from our position, heading towards Graham Spinkston’s 12 Platoon. We couldn’t fire at the retreating enemy as our rounds would have landed amongst Graham’s men. So we stood to at 100 per cent alert for the remainder of the night with eyes as big as saucers and ears like elephants. However, nothing else eventuated that night. I went out with the clearing patrol the next morning and had a look at the area where the enemy had been. There were indications that about a dozen enemy had been crawling towards our position, about 20 feet out in front. They had been inside our claymores. I was now regretting that I hadn’t set up a trip flare across the position to get a better early warning than our eyes and ears could give.

3 RAR had found a huge 300-bunker complex as they swept through the NVA position. The enemy had vacated the position without too much loss but now he had been forced to relocate his position and move out of the province. We were therefore tasked to link up with an American infantry unit on our right flank near the Suoi Nhac River and prevent enemy withdrawal along the river and its banks.

By mid-morning I had made radio contact with the American platoon that was to be across the river from us, and so I arranged a rendezvous to tie up who was going to fire where and so on. We waited for hours for this platoon to arrive at the rendezvous. They finally turned up approaching our position from the opposite direction from where I expected them and they were a sight to see. They were wearing a variety of gear. Some were in shirts and flak jackets, some had shirts on with short or no sleeves and some had no shirt but were wearing a flak jacket. They were all wearing helmets with a cluster of various odds and ends on them, from cigarette packs and chewing gum to plastic C ration spoons, held on by a large wide rubber band. As they approached our position I stood up to get a good look at the first US Army soldiers I would meet. I was hoping they would be more professional than the US Army soldiers I had seen around the Nui Dat base.

The point man or forward scout came into view carrying an M 16 rifle with a 30-round magazine on it and a small compass in his other hand. Behind him came the squad leader who had a carbine and compass as well. The next man into view was the machine-gunner who had his M 60 slung over his shoulder and one hand in his pocket. His second-in-command on the gun was behind him: he had a carbine slung upside down across his back and was carrying two metal ammunition liners, which were the boxes for the linked machine-gun ammunition. We couldn’t believe our eyes. Not one man was capable of firing in the direction his eyes were looking, and most of the remainder of the platoon were in a similar—if not worse—state of readiness. Probably the most striking thing of all was that these soldiers were not wearing camouflage cream on their faces. Because of the tropical heat it was uncomfortable to put over your skin, but it did cut down the shine on your face in the jungle immensely. It was one of the things that my platoon prided itself on: we would be constantly re-applying cam during the day as the sweat removed it.

I showed the platoon commander where to put his men on the ground and set about discussing the finer details of the position. The first question I asked was if he thought I was in the right spot as he had taken so long to find me. He answered ‘Hell no. The goddam track we were following went all over the place and we got a little lost!’ I had heard that the Americans were not as well trained as we may have been, but to walk along tracks in an area where the enemy was known to be operating was just asking for trouble.

It was decided that because it was so late in the day it would take the Americans too long to get across the river and set up their position before nightfall. So they would harbour to our rear and add depth to our somewhat linear position. This also kept them away from us as we weren’t too keen on these guys being up front and drawing unwarranted attention. They had no noise discipline to speak of. They spoke out loud. If a soldier wanted to speak to someone 20 metres away he didn’t go over and talk quietly to him, he simply yelled out. My men were getting a bit twitchy about all the noise coming from the Americans and asked me to go back to their platoon position and speak to their platoon commander. I wandered back toward the American platoon and as I was about half way back I realised I hadn’t told them that I was coming back into their position. Hoping I wasn’t about to get shot by a trigger-happy soldier, I gingerly made my way toward the Americans. I needn’t have worried. Not only did they not have a sentry, but the gun was unmanned and most of the platoon had their backs to the perimeter and were preparing their evening meal. I spoke to the platoon commander who had his first sergeant with him. When I asked if his platoon could ‘rig for silent running’ I received a couple of stares as if I was a creature from outer space. As far as they were concerned they had no problems because my platoon was in front of them and therefore there was no need for great security on their part. I asked the platoon commander if he would come up to where my men were lying in what was virtually an ambush position and listen to the noise coming from his men. He realised I was serious about all this and told his first sergeant to quieten the men down. This he did immediately by screaming out to the whole platoon to ‘put a sock in it you guys, you’re making too much goddam noise’.

While I was talking to the Americans I noticed that some of the squads were preparing to put claymores out. This was of interest to me as I wanted to make sure none were pointed my way. The impression I was quickly gaining was that I would have to check on everything they were doing, or there would be an accident. One of the soldiers was told by his squad leader to site their claymore (they were only carrying about one per squad) out in front of their sector. He grabbed the claymore and the accessories bag and without picking up his personal weapon he wandered off out of the perimeter. He went about as far as the firing lead would take and he nonchalantly opened the folding legs, and from about waist height dropped the mine into the soft ground where it landed, firmly embedded. He turned around toward the squad leader inside the perimeter and at the top of his voice asked if the siting of the mine would do and then strolled back inside the harbour.

I was glad to leave and get back to my platoon. We were beginning to look like world beaters compared with these men.

The next morning the Americans moved to their blocking position. My platoon was to move to a position where we could see the river and its banks, which might be used as escape routes. We therefore had to move past the American position. It was a pigsty. Our policy was always to bury our rubbish in the toilet we dug in the centre of the position whenever we harboured. This did not disguise the fact that you had been in an area, but it did help to conceal how many people had been there, and also your nationality. The platoon standard operating procedure was to dig a latrine big enough to accommodate our needs for the night; before we moved out in the morning we would throw in any refuse from the platoon, and if possible we would have someone defecate on top of any rubbish—so that if anyone was keen enough to dig up our rubbish they got a nasty little surprise as well.

By mid-morning on 9 June I had found a suitable location for our new position. It was in thick scrub with large twisting vines hanging all over the place. However, it did have great fields of fire—and this time we could see whoever would approach our position. I wrote up a quick set of orders and went into the procedure for occupying an ambush. Once again we had no idea exactly how long we were going to be in position. So I went for a two section strength killing group with one section resting in our rear security/administration area. It was useless asking the diggers to stay 100 per cent alert in an ambush for days on end and so a rotation system was the best way to operate. The position was ideally suited to this kind of layout as the administration area was in a small depression in really thick jungle about 35 metres to the rear of the killing group. It took a long time to site this ambush, as the jungle was very thick and the many vines slowed our movement. Also, I was putting the groups of men down on the ground in pairs. But I was prepared to take the time as I didn’t want the position compromised: with our noisy friends on the other side of the river, I figured we had a good chance of the enemy bouncing off the Americans onto us.

By about 1500 hours the platoon was just about settled in, and so I started to get my own position in the middle of the killing group prepared. Because the vines were so thick we needed to cut our way through them to get decent positions where we could fire across the river. Noise was a prime concern so we used our bushmen’s saws to quietly cut our way through the four inch thick vines. I had been going flat out all day and was quite warm from all the running around I had been doing. I had cut my way through half of the vines when I stopped to rest and wipe the sweat from my eyes. A couple of seconds after doing so I started to get the most excruciating pains in my eyes. I was in agony. I moved back to the administration area to see Frank Wessing our platoon medic and see what he could do to help. I couldn’t understand what was wrong with me. Frank and Darryl tried to wash whatever it was out of my eyes but to no avail. The pain was getting worse. I had lost all of my vision and could see only a red blur. Darryl got on the radio and asked company headquarters to send a chopper to evacuate me.

As we did not want to disclose our ambush position we decided that I should move back toward 12 Platoon, who said they had a winch point near their location. With a small escort party I was led back through the jungle looking all the world like one of Damien Parer’s dramatic photographs of a wounded soldier on the Kokoda Trail. The going was pretty rough and I was falling over so often I was becoming a liability. Then the lads threw me onto a collapsible stretcher which our platoon carried, and before long I was saying hello to Graham Spinkston. An RAAF Dustoff (casualty evacuation) chopper quickly arrived and lowered a winch with a Stokes’ litter. I was unceremoniously bundled into the wire stretcher and hoisted up through the trees for what seemed an eternity. The crewman on board gave me a quick once-over as we flew back to Nui Dat. I had lasted all of eight days, had a smell of the enemy and was now a non-battle casualty. I was not impressed.

The doctor at the field ambulance examined my eyes and washed them with a solution which almost instantly reduced the pain to about the level of a toothache and restored my vision, albeit somewhat blurry. Then he gave me the bad news. I was going to have to spend about four days in the hospital with pads on my eyes. After I explained what had happened he believed my loss of eyesight was caused by the sap of the vines coming into contact with my eyes. He said that I shouldn’t suffer permanent damage but as soon as the anaesthetic he had washed my eyes with wore off, I would have to be sedated and made to look like a panda.

I had a quick shower while I could still see and was then stuck into bed and bandaged up. The pain returned with a vengeance and a nursing sister came in and gave me a needle which knocked me out for several hours—for which I was quite grateful. When I woke up I was greeted by my company 2IC Peter Schuman who was back in Nui Dat during operations. He asked me how things were going and told me he would write to my wife as my writing wouldn’t be too legible the way I was. He had brought down some shaving gear for me and made sure I wasn’t lacking anything before he left. Peter visited me several times during the next four days and even sent down a couple of my soldiers to see me.

After four days in the field ambulance I returned to our company lines in Nui Dat. I had to wear dark glasses and keep out of direct sunlight as much as possible. Peter Schuman brought me up to date on what had been happening out on operation Overlord. C Company had had one guy wounded in the leg during a small clash with Viet Cong who were trying to break out of the cordon. His wounds were severe enough for him to have to return to Australia. I thought I had had bad luck. An American chopper had been shot down to the north of where we were operating and a pilot and door gunner had been killed. The bunker system that 3 RAR had found was now being cleared systematically but would still take days to clear and then destroy.

The doctor had another look at my eyes and gave me the good news that I wouldn’t suffer any permanent damage. Peter Schuman kept me busy for the next five days sorting out administration and a few odds and ends. I travelled by landrover into the provincal capital, Baria, about ten kilometres south of Nui Dat, with the company laundry run to fill in my time. It was my first visit into a large town and I was fascinated. The traffic was absolutely chaotic. There was a mixture of military vehicles of all types, overloaded civilian buses, motor cycles and scooters by the score and bicycles by the hundreds. Everyone was busily going somewhere and the only road rule, apart from driving on the right side of the road, seemed to be that the biggest vehicles had right of way. Most of the houses were not much more than shacks and some were made out of the unpressed metal sheeting used for Coca-Cola cans. The government buildings and better style of dwellings were two storey affairs with usually a white or cream cement render finish.

There were a lot of Regional Force and Popular Force soldiers in the town who were undergoing field and weapon training in the nearby area. As we drove through the town to the laundry, I saw the local constabulary. These were Vietnamese who were highly trained enforcers of the law. They were known as ‘the white mice’. Their uniform consisted of black shoes or jackboots; tailored skin-tight grey trousers or jodhpurs, a tailored white shirt and a grey Gestapo-style cap with a silver badge. Around the slender waists of these immaculately dressed men were black leather pistol belts complete with guns and bullets. Most of the guns I saw were 45 Colts or Smith and Wessons and the like. The frightening thing was that the white mice had a reputation for shooting first and asking questions later.

The local people in Baria were considered to be pro-government and consequently one could walk around the town fairly freely even though we still carried our weapons all the time. The Vietnamese women and girls who worked in the laundry were very shy and avoided direct eye contact. Most of the men working in the town were over 40 years of age and any males younger either were in uniform or were cripples of some sort. The more I looked around the more I began to notice the number of young men who were carrying the physical scars of war. The number of limbless people in the town was high and I suspected they lived in town as they would have been unable to carry out the normal agricultural work in a village. As we drove back to Nui Dat I noticed that life centred around a basic agrarian economy with the family plot of land and the sale and bartering of produce being the mainstay of most of the people.

During a short stint on ready reaction duty I was called out to an incident involving the Defence and Employment Platoon from Task Force headquarters on 12 June. They had been contacted by an unknown number of enemy in the rubber north of Nui Dat. Seven men had been killed when what was believed to be a rocket or rocket propelled grenade round struck their armoured personnel carrier and detonated an ammunition liner on top of the vehicle which was packed with claymore mines. We were sent to secure the area to allow battlefield clearance to sort out the horrific mess the APC and its occupants had been left in. The APC had literally had its back taken off and most of one side. The men inside had suffered a similar fate. The injuries to them were massive and probably instantaneous. We assisted in helping to gather the remains of the soldiers in a literal sense. Some of the soldiers had been torn apart by the explosion in the vehicle; so we combed the area in a big circle around the carrier looking for bits of the dead.

Indo-China

Phuoc Tuy Province

Phuoc Tuy Province

Operations 3 June - 12 July 1971

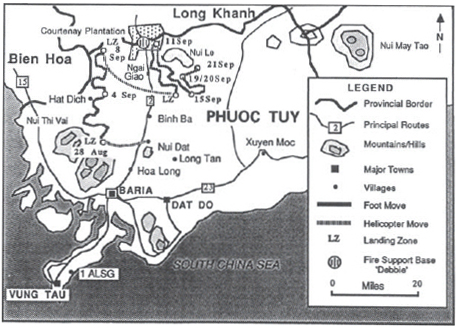

Phuoc Tuy Province

Operations, 28 July - 23 August 1971

Phuoc Tuy Province

Operations, 28 August - 21 September 1971

The 4th Battalion’s officers pose for the official record, after the farewell parade at Lavarack Barracks in April 1971. The New Zealand Second-in-Command, Major Don McIver, had joined the Battalion several weeks earlier; our Kiwi Company was already in South Vietnam awaiting our arrival.

During the crossing-of-the-Equator ceremonies the Battalion faced and conquered three Navy tug-o-war teams. Directly above my head in the photograph is Kevin Byrne. The short haircut on Pte ‘Simmo’ Simpson to the left of the photograph was in vogue at that time.

Day One in Vietnam—365 days to go. Men from Delta Company alight from a US Army Chinook helicopter into the muggy heat of the Australian Task Force base at Nui Dat, with the rubber trees of the abandoned plantation as a backdrop.

Patrolling in the shade of a rubber plantation north of Nui Dat, Corporal Paul Menner leads his section from 10 Platoon through an overgrown section of the plantation. Private Bernie Pengilly, the Company’s first fatality, is centre rear in the photograph.

The Commanding Officer Lt. Col Jim Hughes (far right), and the RSM WOl Wally Thompson (second from left) pay a visit to members from Support Company in the field. With the Battalion operating all over Phouc Tuy Province and dozens of kilometres apart, a personal visit was vital to maintaining the command link.

Gunners from 104 Battery load their Howitzer during a fire mission.

Sergeant ‘Butch’ Porter with his combat load in the bush.

The audience at a concert party at Luscombe Bowl at the end of the airstrip in Nui Dat, enjoy the sight of an Australian girl dressed for the tropical heat. This group returned back into the field almost immediately after the concert.

The Roman Catholic Padre, Father John Carde, celebrates Mass with men from Fire Support base Cherie on Courtenay Hill during operations in Phuoc Tuuy Province.

Private Doug McClelland signals to an incoming helicopter. Private ‘Jethro’ Hannah is at far left holding an M203 5.56 mm rifle and grenade launcher. Note how short the men wore their hair to stay cool and keep clean on the month-long patrols.

The moment everyone looked forward to, mail from home. Captain Peter Schuman (seated at right) and his radio operator devour their letters from loved ones.

An aerial view of the Australian Logistic Support Base at Vung Tau in the south of Phouc Tuy Province. One of the many bunkers protecting this large installation can be seen in the bottom foreground close to the perimeter wire running into the sea.

The strain of being ever alert for sight, sound or smell of the enemy showed on the faces of these two diggers from Delta Company during operations against the Viet Cong. In close country like this, contacts often took place at ranges of 15 metres or less.

The signallers from Company headquarters rest on the track made by the tanks after the bunker battle in July 1971. The close country was difficult to fight through but the tanks proved more than capable.

The Company Sergeant Major, W02 Huish (second from left) listens to the signallers sending in requests for ammunition after the company battle in July. Signaller ‘Paddy’ Leahy is talking on the radio.

The Australian Task Force Base at Nui Dat showing the rubber plantations surrounding the airstrip which could take Caribou short range aircraft. The hill (centre left) was known as SAS Hill after its tenants from the SAS Squadron who enjoyed its panoramic view of the flat countryside.

Two diggers from D Company resting after battle in July 71.

RAAF Iroquois helicopter passes over a troop of Centurion tanks from C Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment. For battlefield mobility the ‘Huey’ helicopter was second to none, and the Centurion quietened all its critics with its ability to fight in the jungle. Without the tank, our bunker battle in July would not have been the success it was.

The armoured personnel carriers move through the Province capital on their way south to Vung Tau on Operation Southward. This heralded the withdrawal of the combatant elements from Nui Dat and the gradual relocation to the departure point for Australian Forces in South Vietnam. Nui Dat was taken over by the ARVN the morning this photo was taken.

After more than four hours on the operating table and with 17 kg of plaster cast surrounding me, I was left out in the sun to dry at the 1st Military Hospital at Yeronga, Brisbane, in May 1972. I came out of plaster on 30 November that year.

The whole scene was incredibly gruesome. The men went about this grisly task in an almost trance-like state. No-one was saying very much and on several occasions men were physically ill. It was a stark reminder of the dreadful damage the weapons of war can wreak on the human form. I was sad; and at the same time I felt a quiet rage inside, wanting to exact revenge for what had happened. The frustrating part about it was that we would probably never know who was responsible for the attack. It could have been the very same civilians we had passed on our way to the destroyed APC and its passengers.

On my return to the base I was greeted by bad news that I would have to pass on when I returned to my platoon out bush. One of my diggers, Phil Asprey, was engaged—and his fiancée had been killed in a car accident. I would have to break the news to him when I arrived in the field. It was a part of my job that I wished I didn’t have to do. The whole battalion was redeploying after operation Overlord: we were now being sent to search for 274 VC Main Force Regiment, which was reported to be operating in the northern end of the province. It looked like the operation was going to be a long one and would probably last another three or four weeks.

Wet weather greeted my return to operations on 16 June and it was apparent the monsoon season was now really with us. Rain was falling regularly every afternoon and if we were unlucky, sometimes in the morning. I used to have a bet every day for a couple of cans of beer with my artillery forward observer’s assistant on what time it would rain. Bombadier Russ Pullen was the forward observer’s assistant and I was amazed at his uncanny ability to guess when it would start to pour down. By the time I was about 100 cans of beer down after ‘doubling or nothing’ and only having an occasional win, I began to suspect that he was contacting the artillery headquarters on the gunner radio net and getting the meterological data every day. I could never prove it but I smelt a rat. The one thing we did smell was a couple of dead Viet Cong that my platoon was tasked to exhume just after I arrived back on the operation. V Company had killed the Viet Cong in a clash about a week earlier and now the Intelligence Section wanted us to dig them up, photograph them, and search for documentation. I had trouble getting volunteers for this—it’s remarkable how the tough guys will sometimes pale away when jobs like this have to be done.

We were now patrolling west of Nui Dat in an area called the Chau Pha (pronounced Chow Far) Valley, trying to locate elements of a Viet Cong unit known as the Chau Duc District Company. We didn’t know it at the time but we were now on an operation called Hermit Park. Quite frankly the names of operations meant very little to us as all we were interested in was where we were going, who the enemy was in our area and how far and how long we would be patrolling. For over a week our efforts were largely unsuccessful as most of the sign we found led away from us heading north and it was old. The sign was usually footpads and tracks left by the enemy in the soft ground. Occasionally we would find a spot where enemy transiting through the area had slept for the night. Our other companies and the APC troop were having more success to the north and closer in to the villages. The APCs sprang a very successful ambush on twenty or more Viet Cong, killing thirteen and capturing four and one surrendering. V Company was back in the thick of it and got stuck into a bunker system with the aid of the Centurion tanks and accounted for about another two dozen. Luckily they had only one NZ soldier killed and about eight troopers and soldiers wounded in action.

The platoon was becoming pretty exasperated at our own lack of contact as we had now been out on patrol continuously for over four weeks. On 24 June things started to look up. We were operating as individual platoons again and the company was sweeping up the Chau Pha Valley either side of the Suoi Chau (River Chau) about 15 km west of Route 2. This put us a long way from the civilian access area in a ‘free fire zone’ where the only people you were likely to meet were enemy. Then one of my scouts spotted some reasonably fresh footprints on a footpad near the river. The country was a mixture of jungle and savannah scrub, with occasional clumps of thorny bamboo. I halted the platoon and took a couple of men from the lead section with me and went for a look around. I was certain I could smell the same smell that I had experienced before and was taking no chances.

Our reconnaissance group carefully made its way through the bush until we came to a large patch of thorny bamboo that must have been about 100 metres across. I wanted to stay close to the river to pick up any sign of water parties or the like, so we moved in towards the creek. Just as we did, I spotted movement to my front. I gave the signal for enemy and to go to ground. About ten metres in front of me I could see the back of a woman in black pyjamas who appeared to be cutting bamboo shoots. I crawled forward to try to see into a depression in the middle of the bamboo clump and ascertain if any more enemy was around.

My sergeant had come forward by now, as we had been gone for longer than I had anticipated. I told him to quietly move the platoon around to the flank of the bamboo in case the enemy tried to get out of the area. I continued to reconnoitre the area of the bamboo, which was around and over a depression in the ground. There were several other enemy in the bamboo whom I glimpsed but couldn’t see for long enough to positively identify as male or female. They appeared to be preparing a staging camp as they were stockpiling firewood and bamboo shoots. After about half an hour or longer of sneaking around this camp I decided to put a machine-gun covering a track leading out of the camp to the west. We would sweep through from the south. I returned to the platoon, gave quick orders and reminded everyone that I hadn’t seen any of the people in the camp carrying weapons, stating at the same time that these may have been left on the ground while they were working.

After ten minutes or so we started our sweep and moved into the camp. We were going slowly as it was difficult to move through the bamboo and scrub. We swept into the camp to find that the women had gone. I wasn’t sure if they had heard us or whether fate had robbed us of our first real crack at the Viet Cong. We searched the camp and determined that they were probably a caretaker group setting up transit camps for groups of Viet Cong who used the valley as an infiltration route into the south of the province.

In the hope that the enemy hadn’t seen or heard us, I asked my company commander if we could ambush the camp for a day or so, in case the caretaker group might return or in case Viet Cong transiting through the camp could drop in. After getting the go ahead, I decided to occupy the camp. It gave good cover and had a water supply handy; and it was easier to cover all the tracks coming into it from the inside. We allotted sections to cover sectors of the camp and laid claymore mines out along the tracks coming into the camp and covered them with machine-gun fire. The forward observer’s assistant registered targets around us to act as ‘cut-offs’ if a big group hit us and covered some minor tracks we couldn’t adequately cover with small arms fire.

The camp had been used about a day before by about a dozen enemy and we were hopeful some more guests would arrive. 10 Platoon had also found a camp further up the river and a pattern was emerging along the river line: 10 Platoon were then moved to try to cut off the enemy that were moving from our location towards them, but to no avail. We settled down to wait.

After three days we still had had no luck. So we used the camp as a base and sent section strength patrols out to look for the enemy. The rest of us were kept busy killing six inch long scorpions, probably the original landlords of the camp. When the scorpions had been disposed of there were always the leeches to keep one amused. The leeches were in epidemic proportions. Being so close to the river didn’t help, and it became a constant battle to keep the buggers off you. Some men had woken up in the morning and had a leech under their eyelids or in their mouths. With the lack of enemy and the leeches’ propensity to want to dine on us continually, I had no choice but to opt for a return to patrolling. This was a lot harder work but it was better than being bored to death and sucked dry.

We moved to rendezvous with the company as our rations were just about out; we also needed a resupply of clothing and various other odds and ends. The company commander was keen on the company not disclosing its whereabouts to the Viet Cong and insisted that we move to a common point to take a single helicopter resupply instead of three independent platoon resupplies. My platoon and 10 Platoon had no trouble getting to the rendezvous with company headquarters but 12 Platoon were having problems. One of Graham Spinkston’s section commanders, Cpl ‘Tassie’ Wilkinson, was unwell and was continually collapsing. Graham could not go fast through the bush with Tassie, so he had lightened the sick man’s personal load so that he was only carrying his rifle and basic webbing. This didn’t help too much; in fact his condition worsened. I was listening to all of this drama on the radio and could feel that the company commander was getting more and more upset as Graham’s platoon struggled towards the rendezvous point with a sick man in tow.

Eventually 12 Platoon asked for a helicopter to evacuate Cpl Wilkinson. However, it appeared the company commander was worried about giving away our position by having a chopper come in and take out a soldier. By now Graham was 5000 metres from the rendezvous and he was worried about Tassie’s condition. By this time everyone was listening to all of the message traffic between 12 Platoon and company headquarters on the radio and the tone of voices on the net was becoming increasingly strained. The moment of truth came when the commanding officer, Lt Col J. C. Hughes, who was coming out to visit D Company in his personal chopper, then landed at our rendezvous. He had been unaware of the drama that had been going on, but quickly released his helicopter to evacuate Cpl Wilkinson.

We spent the afternoon taking a resupply, which was flown in by RAAF choppers, and getting orders for the rest of the operation. The resupply was a fairly slick affair. The company secured the landing zone by surrounding the position with the platoons and posting sentries on any likely tracks. The choppers arrived and while one came into the pad one would circle above to act as cover in case the other took ground fire. A work party from the platoons unloaded all the items; a backload several hours later took out all our unwanted, broken and replaced stores.

Every five days we needed to take a resupply of rations. These were broken down into about three days of US Army C ration, one day’s worth of dehydrated long-range patrol ration and a day of Australian ration. The rations came in 24-hour packs, and except for the US C ration, they were reasonably compact. The American ration was bulky, produced a lot of rubbish from its packaging and was weighty. However, it had a good variety of cans, which meant you didn’t often get the same meal three days in a row On long patrols we had a larger resupply every ten days. Apart from the normal ration resupply we were also given a change of clothes which had been laundered in Baria, a couple of pairs of socks and what was known as the supplementary ration pack.

This sup pack contained cigarettes, tobacco (including chewing tobacco), shaving cream, toothpaste, writing paper and envelopes. I wouldn’t let the diggers use the foam aerosol shaving cream as it had a strong perfumed smell which carried for some distance. In addition to the combat rations our cooks back in Nui Dat made up fresh bread rolls and salad and sent them out on the resupply. But I think the one thing that we looked forward to most of all was a cold carton of milk. Everyone would sit down and open the mail that had come in and slowly drink their milk. It was great to be able to drink something cold and wasn’t warm like the water in our water bottles or a hot brew.

While we packed our rations away and distributed the sup pack, the mail and the other goodies, my medic would go around the platoon and check out the diggers when they shed their filthy greens for clean fatigues. He was on the lookout for tropical ulcers, tinea, and a multitude of other diseases which living in the jungle without bathing for weeks on end could produce. Sometimes we got extra ammunition or grenades to replace ones which had been used or which had become unserviceable through wear and tear in the damp conditions. Radio batteries were always at a premium; I liked to carry at least four of these in the platoon for the two radios plus the mortar-fire controller’s set. It was no wonder our packs were bulging when we took a resupply, as we stuffed everything we could into them. The pack was good for holding about five days’ worth of rations, but add in spare batteries, claymore mines, extra linked ammunition for the machine-gun, grenades, spare socks, waterproof gear and you soon had a pregnant pack.

The diggers would write letters home during the period while we waited for all the administration to be done. The mail was sent out on the choppers which would pick up our smelly greens and other rubbish. Sometimes our RSM, Warrant Officer Class One Wally Thompson, would come out on the resupply chopper and return on the backload. His visits were always welcomed by the diggers as RSM Thompson was an experienced and well-liked soldier. He had a great knack for being able to sit down and chat to the lads, and he knew within a quarter of an hour if anything was astray or what the morale of the platoon or company was like. I had great respect for this man; once I had overcome the initial uncertainty of how to talk to him, I found in him a great store of knowledge on how to handle different situations.

Our resupply day was now almost over. We were then given orders for the next ten days of the operation. We were to continue to sweep north up the Chau Pha Valley, and to clear the area as we went. The day was again punctuated by an incredibly heavy downpour of rain that added to the already high humidity. We therefore spent the night in the company rendezvous, planning to move out at first light the next morning. It was company policy to dig in shellscrapes but as we hadn’t seen hide nor hair of the enemy, none of the platoons had been digging in at night. My thoughts on it were that if you went to all the trouble to conceal your night harbour, why advertise your presence by digging in with a lot of noise? The CSM, Warrant Officer Huish, came around to see the soldiers in the company just before stand to and noticed that my platoon hadn’t dug shellscrapes. He asked me why I hadn’t. I told him; he said I would probably get into trouble if I didn’t dig in.

The next morning just as we were about to leave the company rendezvous, the company commander called me on the radio and asked me to come into his headquarters. This I did and when I walked into his position I couldn’t believe my eyes. Not only was company headquarters well dug in, but Kudnig was sitting in his shellscrape under a hootchie in about a foot of water! I thought he was having a go at me, but when he started to give me a blast for not digging in I knew he was dead serious. The other problem with digging shellscrapes in the wet season was that if you wanted to fight out of one you sometimes needed a snorkel.

Anyway, I took my rocket from the company commander and noticed that the company sergeant major had avoided my eyes as I left to return to my platoon. When I mentioned to my sergeant that I had just seen the company commander sitting in a shellscrape full of water and taking notes, he thought I was pulling his leg.

The next couple of days were memorable in that the company commander was applying pressure on us all the time to cover a lot of ground. It wasn’t easy to keep up the pace that he wanted. We weren’t always in under the canopy of primary jungle and the bush had opened up into areas of woodland with high kunai grass. Patrolling was extremely arduous in this type of scrub. The forward scouts were tiring after only 200–300 metres of bashing their way through the six foot high grass. Before long everyone in the platoon had had a go at breaking the trail. We moved not unlike some African safari in a Tarzan movie. I went forward and had a go at leading. It was damn hard work. The tall grass had to be forced aside by pushing at it with your whole body and when you did that your feet would entangle and make it even harder to stay upright. As one pushed against the grass and opened a passage the hot air trapped at ground level would escape upwards and hit you in the face like a blast furnace being opened.

By two o’clock on the first day of scrub-bashing, I called a halt for the day. We were so exhausted we couldn’t concentrate on what we were doing, and our security was non-existent. I sought shelter from the broiling sun under a copse of trees in this sea of grass. The whole platoon was jammed in an area suitable for about only ten men but I was desperate to get out of the heat and rest the platoon. I was prepared to take the risk.

Major Kudnig was pressuring all the platoons to cover more ground than we were physically able to in these conditions. When he asked me why my locstat hadn’t changed at 4.00 pm, I told him I was looking for a place to stop for the night. He nearly exploded at this remark and told me to continue my patrol, giving me a grid reference to get to by last light before he would consider letting me stop for the day. He wouldn’t accept how hard it had been for us in our area; so we pushed on. Luckily, we broke out of this nightmarish grass plain and back into cooler bush and got to only a kilometre short of where he wanted us when I harboured for the night. We had sacrificed security for our dash through the bush that afternoon and I wasn’t happy about the way the company commander hadn’t accepted my word on what it was like in our area. We weren’t the kind of platoon to swing the lead or bludge; and I was disappointed that indirectly he was criticising our progress. Most platoons could knock over 10–12 km of scrub-bashing a day, but Major Kudnig was asking for 15–18 km—and to go head down and bum up was not possible without jeopardising your security.

On the second day we saw enemy sign leading toward the staging camp. Some of the footprints were quite fresh and gave indications that the owners were carrying equipment. The bushes alongside the track were bent and broken from passing traffic, and looked like they had been damaged only twelve hours before. I was given permission to return and see if the enemy was around. There was sign in the area of the camp but the heavy rains had washed any tracks away and even evidence of our own occupation was difficult to find. We set up our ambush in the camp and set claymore banks out along the trails leading into the camp. We hadn’t been settled down for more than an hour when, right on last light, one of the sentries came scuttling back into the camp to report that a group of enemy was approaching the position. I moved up next to where one of our guns was facing down the track the enemy was moving on. The claymores would account for at least 70 metres of track but the gun was a back-up in case we had a misfire. The silence was deafening as we peered through the gloom of the fading light; my heart was pounding away inside my chest as I began to anticipate the incredible noise that a bank of six claymores was going to create. Finally dark figures were seen moving towards us. I tightened my grip on the firing mechanism for the mines. I could see the first six or seven men and I was just about to press the clacker—when I recognised the scout as one of the soldiers from 10 platoon.

I quickly passed the signal for ‘friendlies’ and told everyone to put on their safety catches. It had been a close call. Had we not waited to observe the rule of engagement—that one couldn’t engage someone unless they had been positively identified as enemy—we would have had a tragedy on our hands. Kev Byrne’s platoon were somewhat disoriented after having been pushed to go like the clappers all day and in fact they were trying to make up time like I had the day before. After Kevin and I compared notes on where we were, he moved to harbour about a kilometre north of our position on the other side of the River Chau.

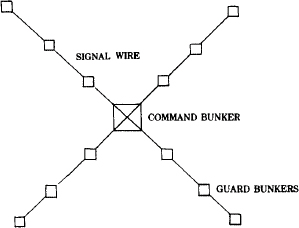

On 2 July the company recorded its first kill. 10 Platoon sprang an enemy caretaker group in an old bunker system where they were preparing the bunkers for reoccupation. They killed only one enemy, but the bunker system was a big win in itself. The bunkers were in five systems altogether (see Figures 1–3) and one tunnel dug into the rich red soil was 1200 feet in length! The whole system was designed like a large X, so that if you assaulted it from any direction you would get caught in a cross-fire from the arms of the cross. Above ground, there were sleeping areas at the entrance to each bunker, so that if the enemy were subjected to shelling or bombing by us, then they simply rolled out of their hammocks and into the shelter of the bunker. Also above ground, was a kitchen complex capable of feeding several hundred men. The smoke from the cooking fires was dissipated by an ingenious method. A length of bamboo ran for about 30 metres along the jungle floor and every two metres or so a small hole drilled into the bamboo filtered out the smoke in such little amounts that it was undetectable by the ever present air patrols.

Underground, the tunnel system was vast and represented an enormous amount of work. The sides of the tunnels looked like they had been carved by some machine. The tunnels descended about 35–40 feet and were about four feet high. One of the tunnels had several rooms for a casualty ward, complete with bunks, and a well, which went another 30 feet down, ensured fresh water for this subterranean hospital. There was no revetting of the sides of the tunnels as the dark red soil was like clay and excellent for digging. The striking thing about the whole complex was the camouflage. It was almost impossible to see one bunker from the next and if you were down on the ground flat on your stomach (as we often were), they were almost undetectable.

We spent the day searching the bunkers for equipment or information on who was destined to occupy the system. Late in the afternoon we heard over the company radio net that Tassie Wilkinson had died. It was both a shock and a shame: Tassie had probably been on his last tour of operational duty. He had been in the army for about fifteen years and had served in Borneo, Malaya and a previous tour in South Vietnam.

Figure 1. Extended lay-out of bunker system

Figure 2. ‘X’-type bunker formation. An assault from any direction brought cross-fire from at least two other bunkers.

Figure 3. Cross-section of typical bunker

We moved north again. My platoon went right up against the Phuoc Tuy and Long Khanh Province border, near the Firestone Trail. We were now looking for sign of the enemy entering into the civilian access area close to the villages. But our only sighting of anyone was a couple of civilians from the village of Thai Thien. They were gathering bamboo shoots and other natural vegetables and it dawned on me that these locals were walking 10–15 kilometres a day just to gather food. The next resupply, commonly known as a ‘maintdem’ (maintenance demand) day, saw our company commander leave the field to go into hospital for an operation for a stomach ulcer. The word quickly filtered down to the troops that Major Kudnig was leaving and that Capt Peter Schuman would be acting company commander. I must admit I was not sad to see Major Kudnig go.

Peter Schuman’s first job when he took over as acting company commander was to give orders for a company area ambush. After we received the most comprehensive, and without doubt, the best set of orders I had ever heard, we moved off to take up our positions. We were ambushing some fairly prominent tracks in the area on supposedly hard intelligence that enemy were in transit through the area to and from the civilian access areas. The Viet Cong were building up their stocks in the border ‘sanctuary’ areas. They were pressing the local villagers into providing cash and food for their troops; often using terror and coercion to achieve their aims. We were out of the primary jungle and into fairly open scrub with fields of fire that reached almost 100 metres. It was a daylight ambush and oppressively hot in our position in the long grass. Torrential rain replaced the heat in the afternoon, which was followed by a short humid spell before nightfall. After dark we went onto 50 per cent alert and spent the remainder of the night resting for an hour and then peering into the gloom for an hour. Unfortunately, the enemy failed to come our way and we pulled out of our position the next morning.

By now the company had been on patrol for just on six weeks. I could feel that we were losing our zip as I was having to correct faults and kick backsides more than ever before. The hard yakka of patrolling in the wet and living on hard rations was taking its toll. It was our first really long stint on operations and the strain of remaining constantly alert and watching your arcs all the time, coupled with the physical effort of scrub bashing and interrupted sleep for gun picquet had worn us out. We were jaded. Most of us had not had a wash throughout the whole patrol save a couple of lads who had been rotated back to Nui Dat for five days at around the four week mark. Those soldiers had been able to clean up and eat real food while doing Task Force perimeter bunker security duties. So I was not the only man in the company who was pleased when Col Hughes pulled us out of the bush on 12 July.

My platoon had covered some 90 km on foot. We had smelt and fired at an indeterminate number of enemy and seen some female enemy who were possibly unarmed. It wasn’t what one would call a successful patrol—but at least we were all alive, at least we had learnt a lot and at least we hadn’t let the enemy get the drop on us.