EPILOGUE

End of an Era

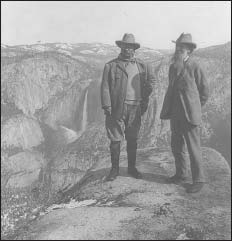

President Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir on Glacier Point, Yosemite Valley, California, in 1903.

THE AMERICAN FUR TRADE DIDN’T END WITH THE NEAR extinction of the buffalo; in fact, it hasn’t ended at all. From the late 1800s up through the present, Americans have continued to kill animals for their pelts and sell them for assorted fashion purposes. Today there are roughly 150,000 mostly part-time fur trappers in the United States, along with hundreds of fur farms, which contribute to an international fur trade that in recent years has generated sales of between ten and fifteen billion dollars.1 This, however, is not the subject of Fur, Fortune, and Empire, which concludes at the dawn of the twentieth century with the rise of the conservation movement.

As it turned out, the buffalo’s plight was a symptom of a much larger problem facing America. The nineteenth century, especially the latter half, has been called the “Age of Extermination,” and for good reason.2 An astounding number of animals were killed to feed the growing population, to respond to the demands of fashion, and for sport; while many more perished because their habitats were destroyed by the relentless expansion of cities, towns, farms, roads, and rail lines. As a result numerous species were dramatically reduced in numbers, some were pushed to the edge of extinction, and a few were wiped off the face of the earth. The buffalo, of course, one of the great American icons, is the poster child for the “Age of Extermination.” But there are many other egregious examples, including the passenger pigeon, and a great variety of plume birds, which were killed solely for the sake of their beautiful feathers, used to adorn hats.3

During the “Age of Extermination” the buffalo was not, of course, the only animal being killed for its pelt. Ever since the American fur trade commenced, a great variety of furs had been purveyed, and in the late 1800s that continued to be the case. For example, there were years during this period in which more than four hundred thousand skunk were killed for their furs, more than five hundred thousand raccoon, and well over 2 million muskrat—and for each of these animals the tallies sometimes went much higher. The latter part of the century also saw a dramatic increase in the number of beaver killed. After years of not being trapped, their numbers had rebounded, and although the market for beaver hats was small, the pelts were still widely used for trimming coats and making muffs. Fur seals and sea otters, too, were once again fashionable, especially after the United States bought Alaska from Russia in 1867, in the bargain of the century. From 1870 through 1890 the Alaska Commercial Company was given a lease by the United States government to kill up to one hundred thousand male northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) annually. For most of those years the company slightly exceeded its quota and sold the skins to furriers who made coats that were very dear. During this time thousands of Alaskan sea otters, prized for their luxurious fur, were also killed.4

The “Age of Extermination” led to a fundamental shift in American society. Inspired by the eloquent and stirring words of, among others, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and John Burroughs, who extolled the virtues of living in harmony with the natural world, Americans grew increasingly alarmed at the devastation they were witnessing—not only the great number of animals that were being killed, but also the virgin habitat that was being lost. They were at long last ready to take action, the ravages of the Gilded Age having ironically created an environmental cri di coeur. Some were intent on preserving nature by keeping human impacts to a bare minimum or, better yet, by having no impacts at all. Others pursued a philosophy that was more in line with emerging tenets of the embryonic conservation movement, which argued that humans should use natural resources wisely and efficiently so they would be there for the enjoyment and benefit of future generations. Driven by one or perhaps both these impulses, a diverse range of private individuals, hunting and birding organizations, and politicians—most famously Theodore Roosevelt—worked during the late 1800s and early 1900s to implement major changes to the way in which humans and the natural world interacted. The results of their efforts ushered in a whole new age, which witnessed the establishment of America’s first national parks, the creation of the National Wildlife Refuge System, the setting aside of the first national forests, and the passage of state and federal laws designed to protect game animals and plume birds.5

This nascent movement created a growing tide of conservationism that had a major impact on the operation of the fur trade as well. By the early 1900s the majority of states had enacted laws regulating the killing of fur-bearing animals, most of which included licensing requirements, and instituted closed and open seasons or in some cases, placed bag limits or outright prohibitions on the taking of certain species. These laws in turn were backed by a federal statute, the Lacey Act, that made it illegal to transport across state lines any wildlife killed in violation of state law. The purpose of these laws was not to hinder or stop the fur trade but rather to ensure that the trade continued indefinitely. The thinking went that by offering the animals protection against indiscriminate slaughter, the laws would guarantee that enough fur bearers remained year after year to sustain significant levels of trapping, thereby generating a healthy annual revenue stream for the trappers and the broader economy. In other words the states were interested in preserving the animals primarily because that was the only way to preserve the fur trade itself. Even when states banned the taking of a certain species because its numbers were too low, the expectation was that once the number of animals increased, trapping would resume.6

An international effort emerged as well to regulate the fur trade. Until about 1880 the hunt for northern fur seals in Alaska was mainly land based and operated by Americans on the Pribilof Islands, which had the largest concentrations of northern fur seals. By annually killing roughly one hundred thousand seals, the Americans were already threatening the long-term survival of the population. The situation grew direr in subsequent years when the United States, Great Britain (Canada), Russia, and Japan ramped up their pelagic (open ocean) sealing operations beyond the shores of the Pribilofs, killing perhaps as many as 75,000 additional seals per year.7 This level of slaughter was unsustainable, and once the four countries realized that, they came together in 1911 to sign a treaty that banned pelagic sealing and allowed land-based sealing to continue on a restricted basis. This treaty also included a provision prohibiting the killing of sea otters, whose numbers were so low that they were on the verge of extinction.8

The rise of the conservation movement and the passage of these state, federal, and international laws, then, represents a transition point in the history of the American fur trade. It unquestionably marks the end of an era. No longer would market forces alone drive the fur trade. Instead there was now also an expanding list of laws and regulations that placed boundaries on the conduct of the trade. For the first time many fur-bearing animals were afforded a measure of legal protection. It is at this transition point that Fur, Fortune, and Empire’s story leaves off, and another begins—one that will have to be written by someone else. Whoever takes up the task of telling the history of the American fur trade in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries will need to consider a whole array of issues—many of them quite prickly—not touched upon here, including the evolution and effectiveness of the laws and regulations; America’s transition from a net exporter to a net importer of furs; the dramatic growth of fur farming and the decline of fur trapping; the development and marketing of faux furs and other shifts in fashion; and the rise of the environmental movement. The story of the modern American fur trade will also need to address the controversial, emotionally charged, and sometimes violent political, moral, and ethical debate over the trade itself, in which various sides square off on a wide range of issues, among them animal rights, trappers’ rights, individual rights, cruelty to animals, the conditions at fur farms, and whether people should wear furs at all.

FOR THE MOST PART THE NEWS ABOUT THE LEADING ANIMAL characters in this book—the beaver, the sea otter, and the buffalo—is encouraging, especially if your base for comparison is where these animal populations stood at the end of the nineteenth century. Beavers, in search of new streams and rivers to dam, have returned to many of the places from which they had vanished long ago. One of the most remarkable reappearances occurred in no less than New York City, when, on February 21, 2007, a keen-eyed observer on the edge of the Bronx River made a startling discovery. There, swimming through the murky water, was a large, brown, furry animal, which looked curiously out of place. It was a beaver, the first one seen in New York City in two hundred years. Christened “José”—in honor of José Serrano, the Bronx congressman who had secured nearly $15 million in federal restoration funds to bring the grossly polluted river back to life—this lone, intrepid beaver continued unperturbed to gather wood and build its lodge, while New Yorkers marveled at the city’s new resident.9 Of course not everyone is happy about the nationwide resurgence of beavers, as evidenced by the many newspaper stories that tell of homeowners and town officials who are angry or frustrated about beavers cutting down trees and flooding formerly dry land—in particular, land that used to be someone’s backyard.10

Also encouraging is that sea otters have rebounded somewhat from their nadir in the early twentieth century, but in many places within their historic North American range, from Alaska down to Baja, there are still either very few or no animals present. And overall the number of sea otters today is but a wisp of a shadow of those that swam majestically in the Pacific before the fur trade commenced. That is why the sea otter populations in most of California and along the coast of Alaska, from the Aleutian Islands to the Kodiak Archipelago, are listed as threatened by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.11 As for the hardy buffalo, it too has rebounded. Beginning with private and public efforts in the late 1800s and early 1900s to protect the few individuals that were left, the buffalo was saved from extinction, and today there are more than five hundred thousand spread out over a combination of parks, refuges, ranches, Indian reservations, and zoos, with most of them being raised for meat production, like cattle.12

THE RUMBLING ECHOES OF THE FUR TRADE OF YORE REMAIN with us today. Dozens of American cities and towns can trace their origins, if not their actual creation, to the fur trade. These include, among so many others, Springfield, Massachusetts; Augusta, Maine; Saybrook, Connecticut; New York City; Pittsburgh; Detroit; Chicago; St. Paul; Green Bay; Milwaukee; St. Louis; Pierre, South Dakota; Leavenworth, Kansas; Pueblo, Colorado; Fort Benton, Montana; and Astoria. Scores of places are named after fur traders and trappers, among them Williams, Arizona; Ogden and Provo, Utah; Duluth, Minnesota; Culbertson and the Bridger Mountains in Montana; Bonneville, Washington; Jackson and Laramie, Wyoming; Craigmont, Idaho; Kit Carson Peak in Colorado; and Walker Lake in Nevada. A mosaic of locales, schools, and sports teams with beaver or buffalo in their name or used as images on their jerseys and flags attests to the ubiquity of these animals at one time, and to their importance in the fur trade. The cultural impact of the mountain man, one of the great icons in American history, remains strong, showing up in our language, our television shows and movies, and at the many reenactments of rendezvous that take place throughout the West. And more broadly, the history of the fur trade is on display at national and state parks, museums, and other historic sights, staffed by trained interpreters who are eager to impart their intimate knowledge of this bygone era.13 Then there are the hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people who can trace their ancestry back to that diverse parade of early Americans—whites, blacks, Indians, métis, and so many others—who created and sustained the fur trade from the 1600s to the 1800s.

Over time, as the thrills and immediacy of the present crowd out the echoes and lessons of the past, it is all too common for people to lose touch with their heritage. It would be a shame if that were to happen with respect to the fur trade. It is a seminal part of who we are as a nation, and how we came to be.