—2—

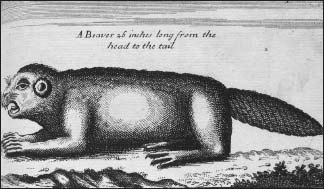

The Precious Beaver

A vicious-looking beaver, with humanlike eyes, from a book published in 1703.

THE DAWN OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY WAS A HORRIBLE time for beavers. Killed by trappers for hundreds of years, the beaver had been just one of many furs in the universe of fashion, and a lesser one at that. Precious sables, martens, and ermines were among the fur elite; beavers were not. Then, toward the end of the 1500s, the evolution of style transformed the beaver hat into a necessary accoutrement for the well bred and well heeled. Suddenly the beaver—one of the world’s most intriguing creatures—became the most sought-after commodity of the fur trade. Its popularity would not be surpassed for more than two hundred years.1

Since the beaver plays such a central role in this book, a brief digression on the animal’s natural history is in order. There are two species of beaver—the European or Eurasian (Castor fiber) and the North American (Castor canadensis)—both of which belong to the largest group of mammals, the order Rodentia, or “gnawers,” which includes other toothy members such as squirrels, porcupines, and rats. The European and the North American beaver differ in their number of chromosomes and a few behavioral characteristics but otherwise are largely indistinguishable; hence the generic term “beaver” will be used from now on. Beavers grow up to four feet long, and weigh as much as 110 pounds, although they average 40 to 50. The only larger rodent is the capybara, or “water hog,” of South America, which also reaches four feet, but can pack as many as 150 pounds onto to its beefy frame. Both the modern beaver and the capybara, however, are lilliputian compared with the extinct giant beaver, which roamed ancient forests alongside woolly mammoths, and may have been up to seven feet long and have weighed nearly 500 pounds.2

A head-to-tail tour of the beaver reveals a range of fascinating features. Up front the four curved orange incisors, two each jutting from the upper and lower jaws, are the perfect combination of form and function, allowing the beaver to gnaw and chip its way through tree trunks up to three feet in diameter.3 Such abrasive work would quickly wear down average mammalian teeth to the gums, but the beaver’s incisors are designed to withstand this punishment and remain sharp. Their first line of defense is that they never stop growing, so what is worn away is quickly replaced. And second, the power of abrasion is an ally. The outer edge of each incisor is extremely dense and hard enamel, while the inner edge is much softer dentine. Thus the inner sides of the teeth wear down more quickly than the outer, keeping them beveled like a chisel, a profile that is further honed by the way in which upper and lower teeth slide past one another each time the mouth opens and closes. However, if one of the incisors breaks off or goes out of alignment, disaster can ensue. No longer impeded by its opposite, an incisor will continue growing, curving back on itself, making it impossible for the beaver to eat, resulting in a slow painful death by starvation. And if the errant tooth is angled in a certain way, it can impale and kill the beaver by puncturing its skull. The mighty incisors are backed up by sixteen deeply ridged molars, and this formidable toothy assemblage is embedded in the beaver’s impressively large and sturdy skull, whose jaw is powered by massive muscles that create the brute chomping force needed to fell a tree, as well as the strength to grind the beaver’s fibrous vegetarian fare, consisting of the bark and small twigs of deciduous trees, the leaves and roots of various aquatic plants, and terrestrial grasses, flowering plants, and berries.4

At the beaver’s hind end is its most arresting and recognizable feature, the flat, lozenge-shaped tail, which accounts for a quarter or more of the animal’s length. While the muscular base of the tail is furry, the rest of it appears to be covered with overlapping scales, such as one might see on a fish or a snake; but appearances deceive, and the scales are merely skin-deep indentations. A highly versatile appendage, the beaver’s tail serves as a support to help the beaver sit upright while scanning its surroundings or gnawing through trees; as a fat reserve; a rudder in the water; and as a body-temperature regulator. It is also an alarm system. When the tail is slapped violently against the surface of the water, it generates a resounding crack that can be heard hundreds of yards away, warning other beavers of danger.5

The beaver’s tail has even played a minor role in the history of religious dietary restrictions. As the author Mark Kurlansky points out, among the Catholic Church’s edicts during the medieval era was one forbidding its followers from eating “‘red-blooded’ meat on holy days…arguing that it was ‘hot,’ associated with sex, which was also forbidden on holy days.” The church, however, had no problem with its followers eating meat that came from animals that lived underwater, for such meat was viewed as “cold” and apparently unlikely to excite libidinous passions. This dispensation was mistakenly extended to beaver tails because, the reasoning went, they were often immersed in water and therefore must be “cold.” Thus, for the 166 holy days during the year, including all Fridays, Catholics could dine on beaver tails without guilt.6 How many actually did so is unknown, but it may have been quite a few, because many who have tasted the beaver’s fatty tail claim it to be quite a delicacy. Indians, too, viewed it as a delicacy, but they also saw the tail in a wholly different light than did the church. Instead of a suppressor of sexual desire, the beaver’s tail was actually regarded by the Indians as an aphrodisiac that could help maintain an erection. Not surprisingly the tail was usually reserved for the sachem or chief, and was, as a seventeenth-century English observer of Indians in lower New England noted, “of such masculine virtue, that if some of our Ladies knew the benefit thereof, they would desire to have ships sent of purpose, to trade for the tail alone.”7

The beaver is enveloped in a lustrous fur coat, usually chestnut brown or reddish in color, but at times black, and on very rare occasions white. The fur comprises two types of hair: the longer, coarser guard hairs, and the softer, woollier undercoat, which together achieve astounding densities ranging from 12,000 to 23,000 hairs per square centimeter. This thick coat provides added buoyancy in water, shields the flesh from the sharp teeth and claws of predators, and keeps the beaver dry and warm. The coat is thickest in the winter, and beavers that live in more northern and colder climates tend to have the thickest pelts of all, which were most prized in the fur trade. In contrast pelts obtained during the summer molting season or in warmer, southern climates were not as plush and therefore were less commercially desirable.8

Although beavers can be found living along the banks of rivers and streams, they prefer ponds. If beavers happen upon a natural pond, they may easily build a lodge or dig a burrow at the edge of the water and move in.9 But if there are no ponds in the area they will often create one; it’s for a good reason, after all, that beavers are called nature’s engineers. Using a structurally impressive combination of logs, branches, mud, and stones, laboriously placed along the axes of streams, beavers construct mighty dams that halt the gurgling rush of water down hillsides and through valleys, thereby inundating the land and forming a pond. To build these natural masterpieces, beavers rely on raw materials that are close at hand, the most important of which is wood, provided by willows, aspens, birches, and other deciduous trees.10 Alone or sometimes in pairs, the beaver sets to work with its powerful incisors, gnawing, cutting, and chipping away the wood near the base of the tree in a V-shaped pattern, often laboring for hours at a time, until the tree is left balancing precariously on a narrow point or wedge of wood, often no thicker than a pencil. With one more cut or a providential gust of wind, the connecting wood fibers rupture as the tree begins to fall. Sensing the vibrations through its teeth or hearing the wood crack, the beaver scampers out of harm’s way. Then the tree topples to the ground—except when it doesn’t. If the tree gets caught in nearby branches, it will remain standing, or listing as the case may be.11 Some people claim that beavers can predict which way a tree will fall, or that they cut the tree so that it falls in the direction of their choosing. This is not true, and a small number of beavers are so clueless on this account that, failing to get out of the way of the crashing lumber, they end up serving as their own executioners, crushed to death by the tree they have just felled.12

Beaver dams in fact reflect the constraints of the environment and the proclivities of the builder. The severed branches and logs, held fast in the vice-like grip of the beaver’s jaws, are dragged into the water to commence construction. Where the current is strong, the dam is usually slightly bowed upstream to best deflect the pressure of the water, and the dam’s foundation is made up of stout limbs driven a short way into the mud, like pilings, and sometimes secured by stones. In more sluggish streams the dam may be perpendicular or concave to flow, and the foundation comprised of sticks, stones, and mud laid on the bottom. From these crude beginnings the beavers build up the width and height of the dam, carefully placing interlocking logs and branches across the expanding structure, and adding stones, mud, grass, and other debris to hold the dam together, give it bulk, and decrease its porosity. A single stream might have one dam or many, creating successive ponds dotting the terrain like a strand of liquid pearls.13

A family of beavers can construct a small dam in a few days, a thirty- to forty-foot dam in a week or so, and a thousand-foot dam in a couple of years, but no matter the length, dams are never truly completed. There are always walls to be shored up and holes to be patched, and the beavers’ seemingly instinctive aversion to the sound of running water makes them very attentive repairmen indeed. Usually many generations of beavers will work on the same dam, which can range in length from a few feet to more than a thousand yards, and in height from barely eight inches to eighteen feet. Regardless of their size and age, dams don’t last forever. Eventually the beavers will exhaust the easily accessible local supply of wood, and when they do, it is time to move on.14

HUMANS VIEW BEAVERS AS NATURE’S WORKAHOLICS, industrious to a fault, and that is why phrases such as “busy as a beaver,” and “eager beaver” are part of the vernacular. “Most people have the idea,” claimed Enos Mills, an American naturalist who spent twenty-seven years observing beavers in the wild, “that the beaver is always at work; not that he necessarily accomplished much at this work, but that he is always doing something.” This is, however, a mistaken assumption. “The fact remains,” Mills continued, “that under normal conditions he [the beaver] works less than half the time, and it is not uncommon for him to spend a large share of each year in what might be called play. He is physically capable of intense and prolonged application, and, being an intelligent worker, even though he works less than half the time he accomplishes large results.”15

It is hard to overestimate beavers’ extraordinary impact on the world around them. When Westerners launched their first explorations of the New World, the North American beaver was likely the most widespread and successful mammal on the continent, found “living almost everywhere there was water, from the Arctic tundra to the deserts of Northern Mexico.”16 About the only places beavers weren’t found were in present-day Florida, the western edge of the arid Southwest, and farthest reaches of the frigid North. Population estimates for beavers at this time range from sixty to two hundred million.17 The effect of the beaver on the environment, even now but more then, remains profound. Beaver ponds reduce turbidity and encourage the settling of sediment, resulting in clearer water, deeper penetration of the sun, and the blossoming of vegetable life. They create valuable wetland habitat for a great variety of animals and plants. When abandoned dams are finally breached, pond bottoms are exposed and are soon colonized by grasses, flowers, shrubs, and trees. Beaver dams are also critical to water conservation and flood control. Wetlands soak up rain, slowly releasing during dry spells, and the dams themselves offer essential service during severe storms, providing a bulwark against the rampaging waters and limiting the damaging impacts of downstream erosion.18

GIVEN THE MYRIAD OF REMARKABLE CHARACTERISTICS AND skills that the beaver displays, it is not surprising that it has fascinated humans for thousands of years. Many Indian tribes have legends prominently featuring the beaver. Northeastern Algonquian peoples spoke of the world originally being enveloped by water, and of enormous beavers, otters, and muskrats diving into the depths retrieving heaps of mud, which the Great Spirit Manitou molded into the landforms that became the earth. One Algonquian tribe, the Amikona, or “People of the Beaver,” believed they were descended from the carcass of the original beaver. The Cheyenne saw the world precariously supported by a great wooden beam, which had been partly gnawed through by the snow-white beaver of the Far North, the father of mankind. If the beaver got angry it would gnaw all the way through the beam, and the earth would fall into a dark abyss. To avoid this fate the Cheyenne refused to eat beaver or touch its skin. And the Paiute of California said that the beaver used its tail to bring fire from the East, and that is why the tail was naked—all the hair was burned off.19

While Indians have created legends about beavers, Westerners have created their own mythology, rife with hyperbole and fantastic claims. Beginning with the beaver’s mouth, the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder claimed, “The bite of this animal is terrible…. If they seize a man by any part of his body, they will never loose their hold until his bones are broken and crackle under their teeth.”20 Although a beaver’s bite would no doubt be quite serious, Henry David Thoreau correctly noted in the nineteenth century that observers such as Pliny have “a livelier conception of an animal which has no existence, or of an action which was never performed, than most naturalists have of what passes before their eyes.”21

Many medieval writers, including Dante Alighieri, believed that beavers were fish eaters. The beaver supposedly dangled its tail in the water, causing a fatty substance to be released that attracted the fish, whereupon the beaver, sensing the arrival of its meal, spun around and seized the fish in its mouth.22 The eighteenth-century French natural historian Georges-Louis LeClerc, comte de Buffon, even went so far as to state baldly, “a beaver has a scaly tail because he eats fish.” This last outrageous claim was too much for George Cartwright, an English entrepreneur who spent sixteen years on the Labrador coast in the late eighteenth century trading in furs and fishing. “I wonder much that Monsieur Buffon had not…[a scaly tail] himself for the same reason; for I am sure that he has eaten a great deal more fish, than all the beavers in the world put together.”23

One of the oldest and most unusual myths surrounding the beaver involves the animals’ testicles, hunters, and castoreum, a yellowish, pungent excretion that beavers use to mark their territory, and that was long thought by humans to have curative powers. The basis of this myth is the belief that castoreum is contained in the testicles, and since hunters often pursued beavers to obtain this valuable medicinal substance, the beavers would cut off their testicles as a means of escape.24 The best explication of the castration myth comes from one of Aesop’s Fables—“The Beaver and His Testicles”—written in the sixth century B.C.: “It is said that when the beaver is being chased by dogs and realizes that he cannot outrun them, he bites off his testicles, since he knows that this is what he is hunted for. I suppose there is some kind of superhuman understanding that prompts the beaver to act this way, for as soon as the hunter lays his hands on that magical medicine, he abandons the chase and calls off his dogs.” Aesop drew from this story the following moral—“If only people would take the same approach and agree to be deprived of their possessions in order to live lives free from danger; no one, after all, would set a trap for someone already stripped to the skin.”25 The moral notwithstanding, the myth has many holes. First, castoreum is found not in the testicles but in the beaver’s castor sacs. Second, the tale of the testicles fails to explain how female beavers, which were also chased for their castoreum, escaped the hunters’ clutches. Finally, even if castoreum were found in a beaver’s testicles, and male beavers were willing to castrate themselves to live another day, they simply wouldn’t be able to do it because not only are the beaver’s testicles very small, but they are also located inside the beaver’s body, making them inaccessible to the animal’s sharp incisors.

Some myths revolve around the beavers’ mode of transporting wood back to their dams and lodges. A seventeenth-century observer claimed that to perform this operation, one beaver would lay a log on his shoulder, keeping it in place with his forepaw, then all the beavers would form a chain, holding “each other’s tails like a team of horses,” and pull the log to their “habitation.”26 Conrad Gesner, a sixteenth-century Swiss naturalist, had an even more unusual view of how this happened. The first step after felling a tree was for the beaver “company” to select one of the “oldest” beavers among them, “whose teeth could not be used for cutting,” get him on his back, and “upon his belly lade all their timber, which they so ingeniously work and fasten into the compass of his legs that it may not fall.” Alternatively the “company” could “constrain some strange beaver whom they meet withal, to fall flat on his back,” and make him the transport vehicle for the wood. Whatever platform was selected, the “company” then dragged the beaver by the tail to the pond. Gesner didn’t doubt the accuracy of this account because he knew of beavers that had been “taken that had no hair on their backs.” And that was good news for the beaver, because Gesner claimed that hunters, upon seeing such bald beavers, and “in pity of their slavery or bondage,” would “let them go away free.”27

Few qualities of the beaver have attained more mythic status than its supposed intelligence. As John James Audubon and John Bachman observed, “the sagacity and instinct of the beaver have from time immemorial been the subject of admiration and wonder. The early writers on both continents have represented it as a rational, intelligent, and moral being, requiring but the faculty of speech to raise it almost to an equality, in some respects, with our own species.”28 Indeed, the number of authors who have seen fit to comment on the amazing “sagacity” of the beaver, and to compare this animal’s mental capabilities favorably with our own, is impressive.29

In the end, however, all this intellectual adoration cannot hide the truth. As Lewis S. Morgan asserted in his 1868 classic The American Beaver, “In intelligence and sagacity…[the beaver] is undoubtedly below many of the carnivora.”30 Scientific statistical analysis supports Morgan’s contention. One way that biologists measure intelligence is by calculating the encephalization quotient (EQ), which compares the size or weight of an animal’s brain to “the expected brain size.” The latter, in turn, is the average ratio of brain weight to body weight across all the species within a certain taxonomic grouping—for example, a class, order, or family. On this scale the beaver is about average, having an EQ of 0.9, which “is intermediate between that of terrestrial rodents of similar size and…squirrels.”31

IT WASN’T, HOWEVER, THE BEAVER’S UNUSUAL PHYSICAL MAKE-UP, its engineering prowess, its work ethic, or its purported intelligence that most excited humans; rather it was the products provided by this rodent. Long before the arrival of Europeans, the beaver was a “commissary” to the North American Indians.32 They roasted the entire beaver and ate its succulent meat. They cut the beaver’s flesh into thin strips, cooked them over a low fire or on a rock under the hot sun, until they were dry and brittle. Then they pounded them, often along with berries, into a paste that was mixed with animal fat and molded into pemmican cakes that lasted for months, if not years, and provided sustenance for sojourns in the wilderness. Less an item of status than a life necessity, beaver pelts were stitched together into warm winter coats, mittens, and moccasins. Tanned beaver skins produced a thin, sturdy leather perfect for belts and summer dresses and shirts, as well as quivers and bags. The beaver’s scapula was used in religious ceremonies, and even its teeth, decorated with carved lines and circles, or colors, were used by tribes, especially in the Pacific Northwest, to make dice for a game of chance.33

Westerners, on the other hand, saw beavers primarily as profit centers. The two most valuable commodities the animals afforded were castoreum and fur. For thousands of years humans killed beavers to get their castor sacs. Once dried, the syrupy and yellowish castoreum turns into a hard, reddish brown, waxy mass, with a musky, slightly sweet odor. Mixed with alcohol, injected into the body, or ingested as shavings or in pill form, castoreum has been touted as a remedy for a dizzying array of maladies, including head-aches, epilepsy, rheumatism, insomnia, insanity, poor vision, and fleas. And at least since the ninth century, castoreum has also been used as a fixative in perfume, to make the scent last longer.34

By the late 1500s beaver fur had become as sought after as castoreum, for that is when hats made from beaver felt came into vogue. At its most elemental the felt-making process involves taking an animal’s shorn fur, agitating, rolling, and compressing the fibers in the presence of heat, moisture, and sometimes grease, to the point where the fibers intertwine so tightly that they form a strong fabric. Although virtually any fur can be used in this process, beaver is “the raw material par excellence for felt” because the hairs of the beaver’s woolly undercoat are barbed, which makes them ideal for interlocking with one another, creating an exceptionally dense, pliable, and waterproof felt that maintains its shape even in the toughest conditions.35

Given that the early history of hats is murky at best, it is not known when or where the first beaver felt hat was made.36 The oldest reference to a beaver hat comes from Geoffrey Chaucer’s late-fourteenth-century Canterbury Tales, which mentions a “merchant” sporting a “Flandrish beaver hat.”37 Over the next two centuries an expanding cadre of professional hatters met the growing demand for “beavers” or “castors,” as beaver felt hats were called. And toward the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, high-quality beaver hats were the most expensive and desired hats not only in England but throughout Europe, where the size and shape of one’s beaver hat had already become a symbol of one’s stature in society.38 The exponential growth in the trade in beaver hats was a mortal blow to the European beaver. As demand for pelts grew, an extinction problem first coursed through Europe, with the circle of death eventually reaching Russia.

DESPITE THE PAUCITY OF BEAVER AND OTHER FURS IN Europe and Russia, and the promise of the fur trade along the Hudson, the Dutch merchants did not rush across the Atlantic to reap the rewards. A trip to the New World was a major investment, which entailed considerable risk. It took time to plan the trip, gather a crew, and outfit the ship. As a result the first Dutch fur-trading voyage to follow in Hudson’s wake didn’t leave Amsterdam until 1611, roughly a year after van Meteren’s intriguing report on Hudson’s voyage arrived in Holland.

While the Dutch were planning to capitalize on Hudson’s discovery, Hudson himself was heading toward his doom. In the spring of 1610, with the backing of a small group of English merchant adventurers, Hudson finally got his chance to captain a voyage that had as its goal the search for the Northwest Passage to the Orient. Since his last trip had disabused him of the notion that the passage could be found along the coast of America, where John Smith thought it might be, this time Hudson planned to follow George Weymouth’s lead and find the passage farther north, in Canada.39 In late April, Hudson and his crew of twenty-two, including his young son, John, sailed out from London on board the Discovery.

Although Hudson reached what would later be known as Hudson Bay, he did not find the passage he was seeking. What he did find, however, was that his crew could be pushed only so far. During a miserable winter on the edge of James Bay (south of Hudson Bay), while the Discovery was immobilized in pack ice and the crew was slowly wasting away, some of the men began complaining bitterly about Hudson’s leadership. They were especially upset with the way the captain dispensed the dwindling provisions, and with his intention to continue searching for the passage come spring, thereby placing them all in further jeopardy, instead of admitting defeat and returning to England. By the time the ice broke up in early June 1611, freeing the Discovery to sail again, the growing discontent of the men erupted into mutiny.

One morning, as Hudson emerged from his cabin in his nightclothes, the mutineers grabbed him and “bound his arms behind him.” They forced him, along with his son, and seven other men—“the poor, sick and lame” among them—into the Discovery’s shallop, “without meat, drink, clothes, or other provision.” For a short while the shallop was towed behind the ship; then the line was severed, and the nine men were set adrift amidst the ice floes. As the shallop disappeared from view, the mutineers searched the ship for food, finding some that Hudson had apparently hidden in the hold. But then, like an apparition, the shallop reappeared in the distance, and the mutineers immediately “set the mainsail and topsails, and flew away as though from an enemy.”40 The haunting image of Hudson, his son, and the other men, huddled together in the shallop as the Discovery raced away, condemned to what must have been a slow and agonizing death, ranks as one of the most tragic and despairing scenes in the annals of maritime history.

The Discovery finally reached London in the late summer of 1611, with eight crewmen on board. Six years passed before four of them were charged with the murder of Hudson and the other men who had been forced onto the shallop. The mutineers pleaded not guilty, and all were acquitted. No trace of Hudson and his fellow castaways, has ever been found.41