—3—

New Amsterdam Rising

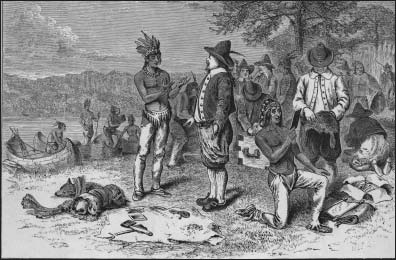

Dutch fur traders at Manhattan.

NOT MUCH IS KNOWN ABOUT THE FIRST DUTCH FUR-TRADING voyage to the Hudson, other than that it was sponsored by the Van Tweenhuysen Company in 1611, on a ship called the St. Pieter (St. Peter), and that it was successful enough to encourage the company to send forth the Fortuyn (Fortune) the following year, captained by Adriaen Block.1 On that equally successful trip Block had the field to himself, and when he returned to America in the winter of 1612–13, it appeared that his luck would hold. Seven weeks after arriving on the Hudson River, however, Block saw a ship in the distance.2 It was a Dutch ship, captained by Thijs Volckertz Mossel, and funded by a rival group of Amsterdam merchants. It too had come to trade.

Block bristled at the sight of this interloper, and the situation worsened when Mossel attempted to “spoil the trade” for Block, offering the Indians twice the amount of goods that Block had been paying for each beaver pelt. To avoid further competition, in which the price for pelts would only rise as the Indians played the rivals off against each other, the two captains set a fixed amount that they would pay per pelt. They also agreed to split the trade, with Mossel receiving one-third of the pelts while the rest went to Block. But Mossel inflamed matters when, just prior to sailing home, he left behind one of his crew, a West Indian named Juan Rodrigues, along with eighty hatchets, a few knives, a sword, and a musket. Mossel swore to Block that Rodrigues had run away, and that the goods were his wages for the voyage, but Block suspected that Rodrigues had been left intentionally, with orders by Mossel to trade with the Indians on his behalf until the ship returned next season. It even appears that Block tried unsuccessfully to kidnap Rodrigues in an effort to thwart the competition.3

The controversy between Block and Mossel followed them back to Amsterdam, where their respective employers took up the cause, each arguing that they had the sole right to the fur trade along the river. Prince Maurice, Holland’s leading nobleman, listened intently to both sides before telling them to resolve their differences. The merchants, however, couldn’t agree to anything. The options of dividing the trade, combining forces, or having one competitor buy out the other were all equally repugnant. Determined and undaunted, each of the merchant companies sent a threatening letter warning the other to back off; and both proceeded to send another ship to America.4

Late in 1613 the two ships entered the Hudson, and the arguments commenced soon after. Mossel and Hendrick Christiaensen, representing the feuding merchants, were furious at the others for trespassing on what they felt was “their” river. While Christiaensen “tried to quarrel and make trouble” between the crews, using “many proud, heated and abusive words,” Mossel took a more direct approach, ramming a canoe full of Indians on their way to Christiaensen’s ship to trade for furs, and then hacking the canoe to pieces, while the Indians fled in terror. One eyewitness suggested that Mossel had resorted to such violent action because he possessed inferior goods, and did not think he could successfully compete for the Indians’ furs. Mossel’s solution was to threaten to drive away the Indians unless he was given part of the “skin-trade.”5

Before things spiraled further out of control, Block himself arrived on the Tijger, in January 1614, and took control of the situation. Block, Christiaensen’s superior in the same company, offered Mossel a deal. Block would take three out of every five furs traded with the Indians, leaving the other two for Mossel. Not long after the agreement was reached, a series of disasters upended their compromise. First the Tijger burned to the waterline, allegedly by accident. Second, members of Block’s crew took Mossel’s ship by force, and after a series of failed negotiations and a subsequent firefight, the mutineers sailed to the West Indies to become pirates. Then, in May, two other Dutch ships, each sponsored by a different set of merchants, arrived, forcing Block and Mossel to rip up their earlier agreement, replacing it with one in which each of the four parties would receive one-quarter of the furs traded on the river.6

Despite these skirmishes the ships returned to Amsterdam in the summer of 1614, bringing back a formidable cache of skins, with Block and Christiaensen alone accounting for 2,500, most of which were beaver.7 Still, given the rancor, the delays, the lawsuits that resulted, to say nothing of the lost ships, the merchants were not happy with the returns on their investments. Yet their anger proved short lived. On March 27, 1614, Holland’s parliament, the States General, issued a General Octroy, or general charter, which invited anyone who had discovered “new Passages, Havens, Countries or Places” to obtain a monopoly on trading in those areas, lasting for four voyages. Rather than fight one another, the once-antagonistic merchants who had sent ships to the Hudson in 1613–14 decided to bury their differences and band together, forming the New Netherland Company. In doing so they applied for a monopoly, not only to trade in and around the river but also up and down the coast. The fact that they didn’t actually discover the Hudson or its surrounds did not bother them in the least; nor did it trouble the States General, which granted the merchants’ application on October 14, 1614, giving them exclusive rights to trade anywhere on the coast, from the fortieth to the forty-fifth lines of latitude—roughly from present-day Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Bangor, Maine—an area that was christened “New Netherland.”8

To anchor its operations in the area, the New Netherland Company quickly built a trading post on the Hudson, allowing its employees, or factors, to trade year round. The post, called Fort Nassau, was built in 1614, on Castle Island, near present-day Albany. It was a formidable redoubt, surrounded by a breastwork, or palisade, fifty-eight feet on a side and an eighteen-foot-wide moat, armed with two heavy and eleven light cannon, and occupied by a garrison of ten to twelve men.9 While the fort seemed impregnable, the island was not. Repeated flooding forced the company to abandon Fort Nassau and three years later to build a new fort nearby, also on the banks of the Hudson.

Being on the Hudson and near the confluence of another major river, the Mohawk, Fort Nassau was an excellent trading hub, strategically located to benefit from the flow of furs coming downriver from the beaver-rich hinterlands. It also provided the Dutch fur traders a place to retreat and fight. In reality, however, fighting was not a viable option. The Dutch were well aware that their pitiful defenses were no match for the Indians, who greatly outnumbered them. This was especially true of the Mohawk, who were part of the Iroquois League of Five Nations, the most powerful Indian alliance in eastern America, which also included the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Cayuga, and the Seneca. So the Dutch tried their best to maintain good relations with the Mohawk, as well as the Mahican (or Mohican) Indians, who inhabited much of the land to the east of the fort.

The New Netherland Company’s monopoly expired in 1618 and was not renewed, most likely because the States General was contemplating establishing a private company—in which the government would have a financial interest—that would be responsible for trading activities in America. The end of the monopoly resulted in a virtual free-for-all that lasted five years. Any group that wanted to mount a trading expedition to the Hudson could, and ships representing rival Amsterdam merchants joined those of the still-dominant New Netherland Company.10 As word spread that the Dutch were ready to trade, an increasing number of Indians brought furs to the posts on the Hudson, as well as to Dutch ships cruising the river. The Dutch in turn journeyed to the South River (the Delaware) and the Fresh River (the Connecticut), and as far east as Narragansett Bay, seeking additional trading opportunities.

WITH MORE THAN A DECADE’S WORTH OF EXPERIENCE, THE Dutch were slowly building up a viable fur trade in America. As Adriaen van der Donck observed in his 1655 A Description of New Netherland, there were persuasive reasons for this success. “The country is truly suited and well situated for commerce: One, because it has fine and fertile land on which everything grows aplenty; two, because its fine rivers and navigable waterways reach many places and enable produce to be collected for purposes of trading; three, because the Indians, without labor and exertion on our part, provide us with a handsome and considerable peltry trade that can be assessed at several tons of gold annually.”11

The trading bonds between the Dutch and the Indians grew stronger over time because both provided what the other wanted. The Dutch side of the equation was simple: The more furs the better, and the best fur of all was beaver. In exchange the Dutch gave the Indians a variety of European goods, including knives, metal pots, glassware, and duffels—coarse, durable, and usually colored pieces of woolen cloth. Guns and liquor, which would soon profoundly alter Indian life in America, were rarely used during this early stage of the Dutch fur trade.12

Particularly key to the trading activities were shell beads, which the Dutch called sewan, sewant, or zeewand, and the Indians and the English called wampumpeag, peag, or wampum. There were two types of wampum: White beads, cut from the inner whorls of whelk shells, and so-called black beads, which were really dark purple and worth twice as much as the white, from the edges of quahogs. Indians along much of the eastern seaboard used wampum for ceremonial purposes, as jewelry, as indicators of status, to pay tribute or to compensate for a wrong, as peace offerings, and as a medium of trade between tribes.13 A seventeenth-century European observer noted that wampum “answers all occasions with them, as gold and silver doth with us.”14 Quickly realizing the importance of wampum as a form of currency they could use to buy furs, the Dutch provided the Indians with metal drills and polishing tools, and soon beads were being manufactured at a rapid rate.15

Thus began the close relationship between the Dutch and the Indians of Long Island, who produced so much wampum that the Dutch referred to Long Island as sewan-hacky, or “land of the shells.” 16 The Dutch would trade European goods to the Indians of Long Island in exchange for wampum, and then use it to trade for furs with other Indians. From this point forward, and for much of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, wampum would have an enormous impact on the colonial fur trade. As a nineteenth-century historian succinctly stated, “Wampum was the magnet which drew the beaver out of the interior forests.”17

SOME HAVE ARGUED THAT EARLY EUROPEAN FUR TRADERS, including the Dutch, took advantage of the Indians, but in fact the Indians rarely saw it that way.18 As the French Jesuit priest Paul Le Jeune observed in 1634 during his stay with the Montagnais, an Algonquian tribe in eastern Canada, the Indians were somewhat amused by the Europeans’ great desire for furs and their willingness to part with valuable trade goods to get them. Le Jeune heard his “host say one day, jokingly, Missi picoutau amiscou, ‘The Beaver does everything perfectly well, it makes kettles, hatchets, swords, knives, bread; and, in short, it makes everything’…showing me a very beautiful knife [he said], ‘The English have no sense; they give us twenty knives like this for one Beaver skin.’”19 Joking aside, the point remains that usually both sides in the trade gave things they didn’t value highly in exchange for things they did, and therefore both sides thought they were getting the better deal.20

Although Indians held beavers in high regard, they had no problem killing them. They had done so for thousands of years to provide food and clothing, and to serve other utilitarian purposes. But such killing was not indiscriminate, and “they killed animals only in proportion as they had need of them,” noted the seventeenth-century French historian and statesman Nicolas Denys. “They never made an accumulation of skins of moose, beaver, otter, or others, but only so far as they needed them for personal use.”21 With the arrival of the Europeans, however, the nature of the Indians’ relationship with beavers and other fur-bearing animals changed radically. As the historian William Cronon observed, “Formerly, there had been little incentive for Indians to kill more than a fixed number of animals…. Precolonial trade enforced an unintentional conservation of animal populations, a conservation which was less the result of enlightened ecological sensibility than of the Indians’ limited social definition of ‘need.’”22 The opportunity to obtain European goods, however, altered this equation and the Indians’ “definition of ‘need.’” When they discovered that all that the Europeans wanted in exchange for their goods were relatively common furs, the Indians launched themselves wholeheartedly into this trade, much to the detriment of local animal populations.23

In effect the fur trade enabled the Indians to improve their standard of living and their status within their tribe and within the broader Indian community at little cost. The Indians’ interest in European goods, however, must not be confused with the desire to accumulate wealth or become rich. Unlike the Europeans, for whom becoming richer through trade was the chief goal, the Indians had no interest in that pursuit. Their goals were more practical and sacred in nature.24 Metal hatchets, knives, and kettles, as well as metal-tipped arrows fashioned from those kettles, performed better and lasted longer than the stone counterparts the Indians traditionally used, and gave the owners of such items added “prestige” among their peers.25 Indians coveted imported glass beads and the shiny copper and brass objects for ornamental and ceremonial purposes; the latter because such objects were thought to be imbued with “spiritual power.”26 European fabric, especially when colored red or blue, was in high demand not only because it was easily made into durable, flexible, lightweight, and relatively weatherproof clothing, but also because it was cheaper than beaver: As the historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich so cogently put it, Indians in northeastern America “gave up…[fur] clothing not because it was inferior to English cloth but because it had become too valuable to wear.”27 Trading beaver pelts for wampum was also seen as particularly advantageous transaction.28

A similar logic held for the Europeans. The iron wares, the cloth, and the various trinkets they traded were fairly common items, in many instances produced specifically for the Indian trade, and therefore of little intrinsic value. Thus trading them for beaver pelts and other valuable furs was an extremely sound business decision.

This is hardly to suggest, however, that the Europeans were always fair traders, or that they always treated the Indians with respect. They most certainly did not. For example, in 1622 a Dutch merchant ascending the Connecticut River to trade with the Sequin Indians decided that the best way to obtain wampum was to kidnap the local chief and hold him hostage until the ransom of 140 fathoms of wampum belt was paid.29 Still, taking the broad view, the notion that Indians were routinely duped or mistreated in their trades with the Europeans, at least at this early period of colonization, is simply not true. After all, the Indians were in a very real sense the customers of the European traders, and one of the key ways of maintaining a profitable relationship with one’s customers is to treat them at least civilly. The traders knew that if they abused that relationship, their Indian partners would be partners no more.30

Nor were the Indians novices when it came to trade. They had been trading among themselves, and across the length and breadth of North America, for thousands of years, and in the century before the Dutch arrived on the Hudson, Indians had honed their skills trading with a range of European explorers, fishermen, and fur traders. If anything, in the early years of the fur trade it was often the Europeans who were taken advantage of by the Indians, who quickly learned the value of furs and became adept at playing traders off against one another to drive up prices.31 As Roger Williams, the highly principled founder of the colony of Rhode Island, who viewed Indians with much more respect and sympathy than did most of his fellow European colonists, observed in 1643, “whoever deals or trades with them [the Indians], had need of wisdom, patience, and faithfulness in dealing; for they frequently say, ‘you lie: you deceive me.’ They are marvelous subtle in their bargains to save a penny, and very suspicious that Englishmen labor to deceive them: therefore they will beat all markets, and try all places, and run twenty, thirty, yea forty miles and more, and lodge in the woods, to save six pence.”32

It would be a mistake, however, to view the fur trade in purely economic, utilitarian, or spiritual terms. To the Indians especially the trade was an important means of forging bonds between individuals and groups. When an Indian exchanged furs with a trader for a metal hatchet, for example, “it wasn’t,” as Cronon notes, “simply two goods that were moving back and forth. There were symbols passing between them as well. The trader might not have been aware of all those symbols, but for the Indian the exchange represented a statement about friendship. The Indian might expect to rely on the trader for military support, and to support him in return.”33 Thus the trade in furs functioned diplomatically, cementing alliances between the Indians and the Europeans that helped to determine the balance of power not only among Indian tribes, but also among the Europeans who would soon be vying for control of the continent.

THE ENGLISH POSED THE BIGGEST THREAT TO THE NEW hegemony established by the Dutch. In 1606 King James I had claimed for England the vast expanse of the North American continent that fell between the thirty-fourth and the forty-fifth parallels of latitude, roughly from present-day Cape Fear, North Carolina, to Bangor, Maine. One year later, and two years before Hudson had even arrived on the scene, the English established their first permanent settlement in America at Jamestown, Virginia. This didn’t bode well for the Dutch, given that it wasn’t until 1614 that they laid claim to New Netherland, which fell entirely within the realm that the English had already declared was theirs. And although Jamestown, located just above the thirty-seventh parallel, lay to the south of New Netherland, it was clear by the late teens that the English were forging ahead in their efforts to colonize farther to the north.34

The New Netherland Company, well aware of English designs, decided that the best way to parry the English and to keep New Netherland was to emulate the English and encourage colonization. In 1620 the directors of the company became aware of an opportunity to lure potential colonists away from the English. This chance was provided by a group of religious separatists, the Pilgrims, who were then living in Holland, and who showed interest in relocating to America. The Pilgrims had already obtained a patent from an English company to settle in America, but they were still trying to figure out a way to fund their trip when the Dutch stepped in.

The directors submitted a petition to the States General in February 1620, noting with great urgency that the king of England was eager to “people” New Netherland “with the English Nation,” and thus “by force…render fruitless” the Dutch “possession and discovery” of that land. There was, however, a way in which the States General might be able to avoid this outcome. The directors said there was, at this moment, “a certain English Preacher [John Robinson],” residing in Leiden, “versed in the Dutch language,” who “has the means of inducing over four hundred families to accompany him hither [to New Netherland], both out of this country and England.” If the States General were to transport these Pilgrims to America, protect them, and give them freedom to pursue their religion, then they would relocate and thereby preserve Holland’s “rights” to those lands.35

The States General took a dim view of this petition. First, the parliament was already well along in the planning stages for a private company, which would oversee activities in America, and it was felt that this new entity should make any decisions about colonization. Second, Holland was intent on going to war with Spain, and now was no time to antagonize England, a potential ally in that war, by colonizing land the English thought was theirs. So on April 11, 1620, the States General rejected the petition. But by then it was academic, since in the interim the Pilgrims had accepted a land patent from a group of London investors called the Merchant Adventurers, which ultimately led the Pilgrims to establish the English colony of Plymouth on the shores of Massachusetts Bay.36

FINALLY, IN JULY 1621, AFTER YEARS OF PLANNING, THE States General chartered the Dutch West India Company, a privately owned monopoly that was charged with making war on Spain and funding the war by developing trade throughout a huge portion of the globe, including North America.37 Before the company could do anything, however, it needed to be solvent, and that meant attracting investors, a task that was hindered by the company’s emphasis on fighting. Therefore, over time, the company’s statements and literature began touting the benefits of trade more than the need for war, and ultimately profits became the company’s prime goal.38 One of the company’s original supporters, William Usselincx, offered a cogent argument for the strategic value of money as a motivator. “If one wants to get money,” said Usselincx, “something has to be proposed to the people which will move them to invest. To this end, the glory of God will help with some, harm to Spain with others, with some the welfare of the Fatherland. But the principal and most powerful inducement will be the profit each man can make for himself.”39 That is why the West India Company focused much of its efforts on establishing a province in the vicinity of the Hudson, where the fur trade, if managed properly, could generate a steady stream of income.

It took the directors of the West India Company a little more than two years to get the company’s financing in order. Almost as difficult as raising capital was rounding up settlers. These were prosperous times in Holland, and it was well nigh impossible to find Dutchmen willing to relocate to the wilds of America. But one small group was eager to emigrate: the Walloons, as the Dutch called them—French-speaking Protestant refugees, driven from Belgium by Spanish persecution.40 Before approaching the Dutch, however, the Walloons—fifty-six families in all—turned toward England. Knowing that their neighbors in Leiden, the Pilgrims, had established an English colony in America, the Walloons wanted to do the same. So in July 1621 they petitioned King James I of England for permission to settle in Virginia, and the petition was forwarded for consideration to the Virginia Company, in charge of granting land patents for that part of America. Although the Virginia Company wanted to encourage colonization, and appeared willing to let the Walloons settle in Virginia, it had no interest in paying for transportation. Since the Walloons couldn’t fund the trip themselves, negotiations went no further.

Rather than give up, the Walloons redirected their search for a sponsor and appealed to Holland. Their timing was propitious. The States General had recently created the West India Company, and both the company’s directors and the politicians knew that settlers would be needed to anchor the company’s new province in America. Therefore when the Walloons presented themselves as prospective settlers, the Dutch welcomed them. And, with the pledge of land in exchange for six years’ working for the company, thirty Walloons left Holland on the New Amsterdam, in late January 1624, bound for the Hudson.41

The settlers arrived in early May, setting foot first on Manhattan Island. From there most made their way upriver to where Albany now stands, to inhabit the soon-to-be-constructed Fort Orange. Others settled on a small island near the mouth of the river (Governor’s Island today), while still others fanned out to establish posts along the Delaware River and the Connecticut River.42 The settlers were pleasantly surprised by their new surroundings, which were nothing like the savage wilderness many of them had imagined. “Here,” one of them wrote in a letter home, “we found beautiful rivers, bubbling fountains flowing down into the valleys…agreeable fruits in the woods…considerable fish…good tillage land…[and] especially, free coming and going, without fear of the naked natives of the country. Had we cows, hogs, and other cattle fit for food…we would not wish to return to Holland, for whatever we desire in the paradise of Holland, is here to be found.”43

The Walloons’ arrival signaled the end of an era. No longer would Dutch fur traders have free rein along the coast. From then on all fur trading in the region was the company’s business. And if anyone had any doubts as to what fur the company wanted most, all they needed to do was look at the seal of the new province, with a beaver squarely in its center, surrounded by a string of wampum.44

The province fared well the first year and half of its existence. On September 23, 1626, the Arms of Amsterdam sailed from New Netherland, arriving in Amsterdam on November 4, bringing with it both news from America and a hold full of cargo. The next day Pieter Schaghen, one of the directors of the West India Company, wrote a letter to the States General, telling the “High and Mighty Lords” that “our people are in good heart and live in peace there,” that they had a successful harvest, and that they had “purchased the Island Manhattes from the Indians for the value of 60 guilders.”45 Soon after this purchase, Peter Minuit, New Netherland’s first governor, gave Manhattan a new name—New Amsterdam—and then, in an effort to improve security and administration, he had the province’s far-flung colonists relocate to New Amsterdam, where he built Fort Amsterdam at the southwestern tip of the island to watch the harbor’s mouth and guard against enemy attacks.

Although the purchase of Manhattan was hardly negligible, it seemed at the time less significant than the cargo aboard the Arms of Amsterdam: 7,246 beaver skins, 853½ otter skins, 48 mink skins, 36 wildcat skins, 33 mink, and 34 rat skins. When this is added to the 4,000 beaver skins New Netherland had sent home in 1624, and the 5,295 it had sent the following year, it becomes clear that the provincial fur trade was progressing rather nicely.46 But, as the Dutch well knew, they were not the only ones looking for furs in America.

THROUGH THE MID-1620S THE FRENCH FUR TRADE IN AMERICA was marked by instability and strife. Monopolies were granted and rescinded on a regular basis, and new companies came and went, with freelance traders consistently cutting into company profits. Periods of open trade resulted in a free-for-all, in which scores of traders competed with one another for furs. Trading posts fell apart due to neglect and decay. And the much-hoped-for colonization of the region commonly referred to as “New France” never materialized; in 1625 there were only twenty permanent settlers in Quebec, who were greatly outnumbered by the transient fur traders. Despite these problems, however, the fur-trading business remained strong. In an average year as many as fifteen to twenty thousand furs, virtually all beaver, were shipped to France.47 During this period French and Dutch interactions were very limited, with only a few instances when fur traders from one group tried to gather furs in what amounted to the other’s backyard.

While the French were busy far to the north, the English were active in the south. In late April 1607, after a four-month voyage across the Atlantic in exceedingly cramped conditions, the hundred or so English settlers onboard the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery arrived on the coast of America at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. A few weeks later, about forty miles from the ocean, on a densely wooded and swampy peninsula jutting out into the present-day James River, the ships’ passengers stepped ashore, inaugurating the Jamestown Colony.48 The most colorful of the settlers was twenty-seven-year-old John Smith, who by his own reckoning had already lived a life worthy of the history books, having survived a shipwreck, pirated in the Mediterranean, fought as a mercenary for the Dutch and the Hungarians, been enslaved by a Turkish pasha, and beheaded three men in duels.49 When Smith—one of the colony’s leaders, and for a time its president—had chance to survey his new surroundings, it seemed to him as if he had stepped ashore in paradise. As he would later recall, “Heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation.”50 He marveled at the profusion of fish and vegetation, along with a great variety of animals, including beaver, otters, mink, and wildcats, all of which had fur coats suitable for trade.51 This latter discovery was no surprise. Smith was very familiar with the voyages of fellow Englishmen—Sir Walter Raleigh, Martin Pring, George Weymouth, and Jamestown colonist Bartholomew Gosnold—who had preceded him to America. Each of these explorers had seen evidence of America’s fur wealth, and some of them even obtained pelts from the Indians.52 Therefore when Smith arrived in Jamestown he knew that furs could be one of the colony’s greatest assets.

Despite the Indians’ eagerness to trade furs, Smith and the other leaders of the colony had little time for or interest in such transactions. Theirs was a more basic struggle—to keep the colonists alive and fed. Nevertheless an illicit fur trade soon developed between the Indians and the crews who manned the supply ships sent from England. The sailors raided the ship’s holds, taking goods to trade with the Indians for furs, baskets, and other commodities. To amend their profits the sailors enlisted the support of colonists, who surreptitiously acted as factors, stealing supplies from the fort and using them to trade with the Indians, and then passing the items received to the sailors in return for a cut of the profits. Over the span of six or seven weeks this secret trade resulted in the disappearance of two or three hundred axes, chisels, hoes, and pickaxes, as well as vast quantities of shot and powder. One ship’s master later admitted that the furs and other goods he had obtained by this means generated a profit of thirty pounds back in England.

Rail as he did against this “damnable and private trade,” there was little Smith could do about it before he departed the colony in the fall of 1609. Over the next ten to fifteen years the Jamestown colony did profit from the fur trade, as scores of traders traversed the region, but by the early 1620s, Virginia had already shifted much of its commercial energy toward tobacco.53

Thus, just when New Amsterdam was emerging on the world’s stage, this small Dutch fur-trading province had little to fear from French competition in New France or from the Englishmen in Jamestown. However, there was a growing English threat to the north, and it came from the Leiden Pilgrims whom the Dutch had rejected as potential colonists in 1620.