—4—

“The Bible and the Beaver”

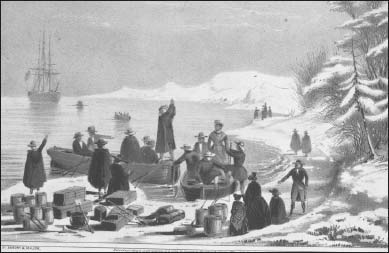

The Landing of the Pilgrims in Plymouth, Sarony and Major, 1846.

VIRTUALLY EVERYBODY KNOWS THAT THE PILGRIMS WHO sailed on the Mayflower were religious dissenters from the Church of England who hoped to establish a colony in America where they would be free to practice their Puritan religion as they saw fit.1 But that is only half the story. Although religious goals were foremost in the Pilgrims’ minds, the Merchant Adventurers, the company sponsoring the voyage, had distinctly less spiritual ambitions. Everyone on that ship was expected to earn their keep and generate dividends for the company in one way or another. If the Pilgrims failed to achieve this goal, the colony would likely fail as well. Nobody was more aware of the economic imperative hanging over the voyage than William Bradford, one of the Pilgrims’ leaders. And during the sixty-five days that the Mayflower spent at sea before sighting land at the tip of Cape Cod, Bradford must often have wondered which of the New World’s many commodities—fish, furs, or timber—would enable this venture to earn a profit. As it turned out, the beaver, an animal that had been extinct in England for at least one hundred years, provided the answer.2 And more to the point, beaver pelts, something that none of the Mayflower’s passengers had ever seen before, would prove to be their economic lifeline for the future.3 As James Truslow Adams noted, “The Bible and the beaver were the two mainstays of the young colony. The former saved its morale, and the latter paid its bills, and the rodent’s share was a large one.”4

On the eve of the Pilgrims’ departure all signs pointed to failure: The entire run up to that moment had been a series of disasters, disappointments, and frustrations, producing an atmosphere of growing anxiety and foreboding. In June the Pilgrims discovered, much to their astonishment, that the Merchant Adventurers had yet to secure transportation for the voyage, forcing the Pilgrims to purchase a ship, the Speedwell, to get them from Holland to Southampton. By the time the Pilgrims finally arrived in England in late July 1620, the company had acquired another ship, the Mayflower, but everything else surrounding the voyage remained in disarray.

The original agreement drawn up by the company seemed fair to the Pilgrims. It would bind them for seven years, during which they would work four days of every week generating returns for the company and two days for themselves, with the last day set aside for worship. Each colonist older than sixteen would get one free share in the venture, and during the seven-year period all living costs and supplies would be provided out of the company’s joint stock. When the seven years concluded the shareholders would split the profits, and the colonists would own the land their houses stood on and the houses themselves.5 But then—unilaterally and the last minute—the Merchant Adventurers, fearing that earnings would not be sufficient, altered the terms of the agreement. Now the Pilgrims would be required to devote all their time to company business, and the land and the houses would be common property, subject to division among the shareholders on a pro-rata basis—conditions the Pilgrims viewed as being “fitter for thieves & bond-slaves then honest men.”6

Although the Pilgrims’ representative signed the hastily revised agreement, the larger group refused to compromise, greatly offending the company’s representative, Thomas Weston, who stormed off, leaving the Pilgrims “to stand on their own legs.” On his way out Weston refused even to pay the one hundred pounds needed for the Mayflower and the Speedwell to satisfy all their debts and clear port, thereby forcing the Pilgrims to sell some of their precious supplies. It was a bitter sale, which Bradford said, left the Pilgrims with “scarce…any butter, no oil, not a sole to mend a shoe,” and not enough swords, muskets, or armor to protect themselves adequately.7 Also problematic was the issue of who would be making the voyage. Because of mounting fears about the terms of their employ, the voyage itself, and what perils might await them in America, many Pilgrims backed out, leading the company to add fifty-two nonseparatists to the passenger manifest, a move that alarmed the Pilgrims, who viewed these “Strangers” with considerable suspicion.

Problems continued when the first attempt to leave England was aborted. The Speedwell didn’t live up to its name, leaking so badly that it couldn’t be repaired, becoming a total loss. By early September the situation was dire. Although the Mayflower was packed to more than capacity, the would-be colonists had already eaten nearly half their provisions, and by leaving so late in the season, the ship was bound to encounter inclement weather on the notoriously tempestuous Atlantic. When the Mayflower finally did set sail, on September 6, 1620, Bradford noted, perhaps with more than a tinge of optimism, that they were accompanied by a “prosperous wind.”8 Unfortunately it didn’t last long.

The Mayflower soon encountered “many fierce storms, with which the ship was shroudly shaken, and her upper works made very leaky.”9 The flooding and cracking of timbers were so bad that many onboard wanted to turn back, but with makeshift repairs and prayers to God, they continued, finally sighting the tip of Cape Cod two months later on the morning of November 9. The Pilgrims deemed what they saw in the distance to be a “goodly” land that was “wooded to the brink of the sea.”10 As much as the forests beckoned, they quickly realized that they were in the wrong place. Their land patent gave them permission to settle in the vicinity of the Hudson, not some two hundred miles to the north, so they began sailing south only to have their progress arrested by “dangerous shoals and roaring breakers” near the Cape’s elbow.11 Deciding that safety was more important than fidelity to the terms of an English patent, the Pilgrims turned around and on November 11 came to anchor in the relatively calm waters of modern Provincetown Harbor. A little over a month later, after a difficult and often frustrating expedition to find a suitable spot for a settlement along the coast, the Mayflower’s tired and sickly passengers stepped ashore in Plymouth.

IT WAS A STRANGELY DESOLATE PLACE. ALTHOUGH THERE were “cornfields” and other signs that Indians had cleared the land, there were no Indians, and no physical record of native settlement.12 Yet just fifteen years earlier Samuel de Champlain, on one of his explorations of the American coast, had drawn a beautiful map of this area, showing it to be a thriving Indian community with numerous wigwams, planted fields, and Indians walking along the shore. The dramatic shift was attributable to the “great sickness” or plague. Sometime around 1616–19 an epidemic had struck the region, most likely sparked by a contagion introduced by European fishermen or fur traders, to which the Indians had never been exposed and to which they had no immunity. Although the exact cause and nature of the epidemic is still debated among historians, its impact is not.13 The few thousand Indians living in the vicinity of Plymouth were virtually exterminated, while tribes farther away suffered devastating losses, with up to 90 percent mortality. The Pilgrims viewed this outcome as God’s work, with a seventeenth-century historian noting that “divine providence [had thereby] made way for the quiet peaceable settlement of the English in the depopulated territory of those [Indian] nations.”14 Another historian of that era claimed that with the epidemic, “Christ (whose great and glorious works the Earth throughout are altogether for the benefit of his Churches and chosen) not only made room for his people to plant; but also tamed the hard and cruel hearts of these barbarous Indians.”15 But if this was God’s work, it was truly horrific. One of the Pilgrims, exploring the coast, commented that so many thousands of Indians had been struck down that they had been unable to “bury one another; their skulls and bones were found in many places lying still above ground, where their houses & dwellings had been; a very sad spectacle to behold.”16

With the Plymouth colonists having come ashore at the onset of winter, there was no talk of trade or profit making. Survival was the paramount goal; the rest could wait. By March 1621, as the land began its verdant turn toward spring, Plymouth was a community on the edge. Nearly half of the 102 people who had boarded the Mayflower lay dead, and of those that remained, only six or seven were “sound” enough to minister to the sick. On March 16, however, the colonists’ fortunes took a turn for the better. That morning a tall, confident Indian walked “boldly” into the midst of Plymouth, at first alarming the colonists. But alarm turned to amazement when the Indian “saluted” and shouted out, “Welcome Englishmen!”17

Samoset was an Abenaki sachem from Pemaquid Point in Maine, who had learned “broken English” from fishermen who frequented the coast. He asked for beer, and the colonists fed him “strong water probably [probably aqua vitae], and biscuit, and butter, and cheese, & pudding, and a piece of a mallard, all of which he liked well.” Samoset told them about Patuxet, the area in which they had settled, and of the local Indians, especially Massasoit, the great sachem of the nearby Pokanoket.18 Samoset spent the night, and the next morning the colonists gave him “a knife, a bracelet, and a ring.” They asked him to bring these to Massasoit and have him and his men visit Plymouth, bringing with them “such beaver skins as they had to truck [trade].”19

Massasoit, along with Samoset and a large group of warriors, arrived at Plymouth five days later. This meeting was especially auspicious. First, it resulted in a treaty of peace between the Plymouth Colony and the Pokanoket. Second, it introduced the colonists to Squanto or Tisquantum, a Patuxet Indian who had been kidnapped from the area in 1614 by the Englishman Thomas Hunt, and sold as a slave in Spain, only to end up living in England. In 1619 Squanto accompanied the English explorer Thomas Dermer on a voyage to New England, and in the summer of 1620, when Indians on Martha’s Vineyard attacked Dermer’s expedition, Squanto was taken prisoner and eventually placed under Massasoit’s care. During the negotiations over the peace treaty with the Pilgrims, Squanto used his facility in English to serve as Massasoit’s interpreter. Once the treaty was concluded Squanto stayed with the colonists, becoming not only their interpreter but also, according to Bradford, “a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation.” Squanto taught the colonists how to plant corn, where to catch fish and obtain “other commodities,” and also served as their guide to the surrounding countryside.20

THE INITIAL MEETING BETWEEN MASSASOIT AND THE COLONISTS was also significant because it inaugurated Plymouth’s fur trade. The Plymouth men had asked Massasoit to bring beaver pelts to trade, and he did.21 Six months later the Plymouth men set out on their first fur-trading expedition. On September 18, 1621, around midnight, Miles Standish, Plymouth’s military leader, along with nine colonists, Squanto, and two other Indians, began sailing their shallop north along the coast to visit the Massachusetts Indians. In addition to procuring furs the men hoped to “see the Country” and “make Peace” with the Indians.22

Over the next four days the expedition explored what is now Boston Harbor and the lands surrounding it. Seeing such a beautiful, broad, deep, and protected harbor, fed by mighty rivers, the Plymouth men realized they had made a mistake. This would have been a much better location to settle than Plymouth, which had a relatively shallow harbor and no great rivers connecting it to the fur-rich hinterlands. But although the men wished “they had been there seated,” it was too late to make a change.23

Finding Indians to trade with proved difficult. On his visit to the area in 1614 John Smith had declared it to be “the Paradise of all those parts.” The harbor’s islands, which he estimated might have had nearly three thousand inhabitants, were planted with corn, fruit trees, and beautiful, well-tended gardens. The coast was cultivated as well, and had “great troupes of well proportioned people.”24 The scene that greeted Standish and his men, in contrast, was of a ravaged landscape, with overgrown fields and all the people “dead or removed.”25 The same disease that had hit Plymouth had killed most of the native population, and many others had succumbed to intertribal warfare. When Standish finally found a small group of extremely fearful Indians a few miles inland, and made clear to them that he and his men had come in peace and wanted “to truck,” the Indians relaxed. The women accompanied the men back to their boat; along the way they “sold their [fur] coats from their backs, and tied boughs about them, but with great shamefacedness (for indeed they are more modest than some of our English women are).” Before departing with “a good quantity of beaver,” Standish promised to return.26

The success of this expedition did not come soon enough to satisfy Weston. He had expected the colonists to start generating profits almost instantaneously upon arriving in America, and when the Mayflower returned to England in April 1621, its cargo being ballast and a few Indian artifacts, Weston exploded. He dashed off a sharply worded letter to John Carver, the first governor of Plymouth, complaining about the empty ship and warning the colonists to do better next time. “That you sent no lading…is wonderful,” wrote Weston sarcastically, “and worthily distasted. I know your weakness was the cause of it, and I believe more weakness of judgment, then weakness of hands….. Consider that the life of the business depends on the lading of this ship.” This letter arrived in Plymouth, onboard the Fortune, in November 1621. In the interim Carver had died and Bradford had been elected governor, so it was up to him to take up the reply, which was essentially: You insult us with your unfounded accusations, we were barely able to stay alive and bury our dead much less engage in trade, and we hope you will forget our “offenses” and move on.27

In addition to Weston’s excoriating missive the Fortune brought thirty-seven colonists, a new land patent to the area where the Pilgrims had settled, and a renewed plea from the Merchant Adventurers for the colonists to consent to the harsh terms that had been proposed just prior to their departure from England—namely that all their days for seven years be devoted to earning returns for the company. The contract still rankled, but the colonists felt they had no choice, so they signed. Wanting to prove their worth to the company, the colonists quickly loaded the Fortune with “two hogsheads of beaver and otter skins,” worth five hundred pounds—roughly 60 percent of the value of the ship’s cargo—and sent it back to England.28 Ironically, given its name, the ship had the misfortune of being captured by a French man-of-war on its return and stripped of its cargo before being allowed to sail to its destination. The Merchant Adventurers were understandably dismayed by the loss, but they were also encouraged by the fact that the colonists had sent any furs at all. The colonists had clearly gotten the message, and from then on the company expected furs to be part of every shipment.

THE COMPANY HAD FROM THE START WANTED THE COLONISTS to succeed at fur trading, but it did little to help them achieve this goal. Despite the fact that it was common knowledge that to obtain furs from the Indians one needed items to trade, the company failed to supply the Mayflower with the traditional goods that would appeal to the Indians. Thus, when the colonists began bartering for furs, they had, as Bradford observed, to rely on the “few trifling commodities [they had] brought with them at first.”29 The colonists pleaded with the Merchant Adventurers to stock them adequately, but the response was anemic at best. Largely left to shift for themselves, the colonists improvised.

The leaders of Plymouth soon realized that the Indians wanted corn, and once the colonists’ harvests improved, they were quick to convert their surplus corn into beaver pelts.30 The colonists also took advantage of opportunities to obtain European trading goods whenever possible, as when the English ship Discovery sailed into Plymouth harbor in August of 1622. Fitted out for the Indian trade, the ship had plenty of beads and knives. The Discovery’s captain, Thomas Jones, was happy to sell these goods to the colonists, but since he knew he had the upper hand, he imposed a high price. In no position to haggle, the colonists offered “coat-beaver at three shillings per pound, which in a few years after yielded twenty shillings [and] by this means they were fitted again to trade for beaver.”31 On another occasion, in 1626, hearing that an English plantation or settlement, on Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine, was ready to “break up,” Bradford and fellow Pilgrim Edward Winslow, along with a few other colonists, took a boat and “went thither,” purchasing five hundred pounds’ worth of trading goods, one hundred pounds of which came from a French ship that had been cast ashore a few months earlier.32

HAVING THE GOODS TO TRADE FOR BEAVERS IS ONLY half of the equation; you also need beavers. And here, several factors—biology, geography, and the impacts of the plague—posed serious obstacles. Because beavers do not migrate over great distances and have a relatively low reproductive rate, intense hunting can easily wipe out local populations. Thus the pressures of the fur trade quickly stripped all the beavers from the woods and meadows in the vicinity of Plymouth. And because Plymouth lacks large navigable rivers, there was no easy route for furs from the interior to be transported to the Pilgrims. Finally the plague wiped out many of the local Indians who would have been the Pilgrims’ most logical trading partners, and who could have served as a bridge to tribes farther away, where furs were more plentiful.

The colonists overcame these obstacles by traveling up and down the coast, seeking out Indians who had furs to trade. Standish’s trip to Boston Harbor in 1621 was the first such expedition, and it was followed by others, including one in 1625, when Edward Winslow and fellow colonists loaded a shallop with corn and sailed “40 or 50 leagues to the eastward,” to Maine, where they ascended the Kennebec River and traded their corn with the local Indians for “700 pounds of beaver, besides some other furs.”33 These ventures, although they might appear insignificant, loomed very large in the life of the colony. As Bradford wrote, during these early years of Plymouth’s existence, “there was no other means [beside the trade in furs] to procure…food which they so much wanted, and clothes also.”34

Reliance on the Indians as suppliers of pelts would become a leitmotif for the American fur trade for more than two hundred years, during which time the Indians became, according to the historian Harold Hickerson, “a kind of vast forest proletariat whose production was raw fur and whose wages were drawn in goods.”35 As William Wood, an Englishman who lived in Massachusetts for four years, wrote in 1634, the colonists were not well suited to take up the hunt. The “wisdom” of the beaver “secures them from the English who seldom or never kills any of them, being not patient to lay a long siege or to be so often deceived by their cunning evasions, so that all the beaver which the English have comes first from the Indians whose time and experience fits them for that employment.”36

The Indians employed many hunting methods in their pursuit of beaver. They used traps on land and nets in the water, baited with the wood the beavers ate. Sometimes the Indians’ dogs would catch the beavers.37 Indians would also damage parts of the dam, and shoot the beavers with arrows and spears when they came to mend the breach, or, if the pond was frozen over, the hunters might kill the beaver by taking advantage of its need for air. In the latter case the Indians first destroyed the beaver lodge, forcing the beavers to escape through plunge holes into the water. Knowing that the beavers would seek out “the hollow and thin places between the water and ice, where they can breathe,” the Indians would find these spots using their clubs, one side of which was tipped with a “whale’s bone,” while the other had a sharpened “iron blade.” The Indians tapped the ice with the tip of the bone, and when a hollow space was found, flipped the club over and used the blade to make a hole, “looking to see if the water is stirred up by the movement or breathing of the beaver.” If it was, they used a “curved stick” and their club to grab the beaver and smash its skull.38

The dead beavers were then given to the Indian women to be skinned, a relatively tedious job that began with cutting off the beaver’s legs at their base, then slitting the animal from the underside of the chin to the tail. Starting at the edges, the pelt was slowly sheared and pulled away from the body, making every effort to cut off as much of the meat and fat as possible. After further cleaning and preparation, the oval pelts would travel one of two paths. Many were cut into rectangular pieces and stitched together by the Indians, then worn as robes for a year or more before being traded to the Europeans. This coat beaver, or castor gras as the French called it, was the most valuable because nearly all of the pelt’s coarse guard hairs—which stick out beyond the soft woolly undercoat, and would otherwise have to be time-consumingly plucked out and discarded during the felting process—were already removed as a result of the constant friction between the pelt and the Indians’ bodies. As an added bonus the Indians’ perspiration thickened the remaining hairs, making them easier to felt and giving them a lustrous sheen.

Pelts not incorporated into robes were stretched on branch hoops, using animal sinews threaded through the edges, and dried in the shade for a day or two. The pelt was then scraped to remove the last vestiges of meat or fat, and dried some more. When the pelt was finally removed from the stretcher, it was as stiff as a board and ready for trade and transport. Such pelts, called parchment beaver, or castor sec, by the French still had guard hairs in place, and therefore were of lesser value than castor gras. No matter how the pelts were prepared, it was extremely important that it be done properly, because shoddy work could lead to maggot and moth infestation, rendering the pelts worthless.39

THE PLYMOUTH COLONY HAD PLENTY OF COMPETITION FOR THE fur trade. Along the coast small plantations were cropping up, virtually all of which planned to earn their keep by trading for furs.40 The most surprising and least successful of these plantations was the one established by none other than Thomas Weston. Early in 1621 Weston decided to “divorce” himself from the company of Merchant Adventurers and strike out on his own, thinking that he knew much better than the Pilgrims how to make a business of trading furs in America. The company warned the Plymouth Colony of his plans to establish a settlement nearby and absorb as much of the trade as possible for himself, and perhaps to take what supplies he wanted from the colonists either by force or guile.41

A year later, when Weston sent more than “60 lusty men” to start his operations, he showed that he had learned almost nothing about achieving success in America. The men, who soon proved to be “rude fellows,” whom the historian Samuel Eliot Morison claimed “were the riffraff of the London slums,” came with virtually no food or supplies, and only through the kindness of the colonists, who allowed them to stay in Plymouth, did they make it through the next few months.42 In the fall Weston’s men moved to Wessagussett, near modern-day Weymouth on the edge of Boston Harbor. Totally out of their element, the men not only fell apart physically, unable even to feed themselves adequately, but also antagonized the nearby Massachusetts Indians, who in turn became aggressive toward them. When the Plymouth colonists learned from their ally Massasoit that the Massachusetts Indians were planning to destroy the small settlement at Wessagussett as well as Plymouth, they went on the offensive. Along with a small force Standish visited Wessagussett, the plan being to foil the Indians’ plans by killing as many of them as possible. After inviting some Indians into a house under the pretense of sharing a meal, Standish and his men sprang their trap, stabbing the Indians to death. The brief battle spread beyond the house, with more Indians being killed and Standish’s men emerging victorious.43

Saved from certain death, most of Weston’s men decided that they had had enough and got in their ship and sailed to Maine. Not long after they departed, Weston arrived in America in a most curious fashion. The Council of New England—the organization that controlled the issuance of land patents for northern New England and the governance of the region—had ordered Weston to stay away from the area, so he disguised himself as a blacksmith, assumed an alias, and crossed the Atlantic on a fishing vessel, landing on the coast north of the Merrimack River.44 Hearing of the “ruin and dissolution” of his colony, Weston sailed south to see what could be done, but his shallop was caught in a storm and wrecked on the shore of Ipswich Bay, where he was captured by Indians and stripped of all of his possessions. Bare-foot and with only the shirt on his back, he made his way to a nearby trading post, borrowed clothes and finaly traveled to Plymouth, where he had the temerity to ask its leaders to stake him some beaver so that he could get back on his feet while he waited for one of his ships to resupply him. Although they remained angered with their erstwhile supporter for castigating them and failing to send them promised supplies, Plymouth’s leaders took pity on this forlorn character, and decided that brotherly forgiveness was the order of the day. They gave Weston one hundred beaver skins and sent him on his way. Weston ultimately established a base of operations in Virginia and made a few trading trips to Maine, but, true to form, he “never repaid” the colonists for their kindness, as Bradford bitterly recalled, and instead offered only “reproaches and evil words.” After a few years Weston returned to England, where he died in debt.45

ANOTHER SOURCE OF COMPETITION FOR THE PLYMOUTH Colony was the scores of ships frequenting New England, whose crews had come to fish and trade for furs. By 1624 there were already nearly forty English ships alone cruising Maine’s coast.46 Although the Plymouth colonists didn’t like sharing potential profits with these itinerant traders, it was what the fishermen traded that bothered Plymouth the most. To gain an edge in the fur trade, these “interlopers” trafficked in guns. This was not a new development (for many years fishermen-traders from various countries had traded firearms with the Indians), but by the mid- to late 1620s its scope had expanded. And as the Indians became more familiar with guns and their great value in hunting and warfare, their desire for guns only grew stronger, making them even more eager to trade furs to arm themselves. Thus each year more guns made their way into Indian hands.

The arming of the Indians greatly alarmed the Plymouth Colony. Their main defense against Indian aggression had been their superiority in firepower, but now that superiority was challenged. Writing about these times, Bradford gave full vent to his emotions. “Oh! that princes and parliaments would take some timely order to prevent this mischief [supplying Indians with guns and powder], and at length suppress it, by some exemplary punishment upon some of these gain thirsty murderers (for they deserve no better title) before their colonies in these parts be over thrown by these barbarous savages, thus armed with their own weapons, by these evil instruments, and traitors to their neighbors and country.”47 Making matters worse, the English fishermen were openly flouting King James I’s 1622 proclamation prohibiting trading firearms to the Indians, a law put in place specifically to protect his majesty’s subjects overseas.48

Virtually powerless to stop the fishermen from engaging in this trade, the Plymouth colonists were not the only ones who were impotent. In June 1623 Capt. Francis West sailed to America on the Plantation, at the behest of the Council of New England, which had given him the grandiose title of “Admiral of New-England.” Outraged that these upstart fishermen were ignoring the requirement that they obtain a license from and pay a fee to the council before fishing or trading along the coast, it instructed West to compel the fishermen to comply. Outmanned and outgunned, West failed miserably, finding that his foes were “stubborn fellows,” much too “strong” to be put in their place by the likes of him and his meager force.49

WHILE PLYMOUTH HAD NO RECOURSE AGAINST THE TRANSIENT fishermen-traders, it was an entirely different situation when men settled nearby and began trading guns for furs, as was the case with Thomas Morton and his associates, who set up operations on the shores of Boston Harbor. Born in Devon around 1576 to an Anglican family of some aristocratic bearing, and trained in law, Morton referred to himself as “Thomas Morton of Clifford’s Inn, Gent.” Others were less kind. Bradford designated him a “kind of pettifogger” who had “more craft than honesty,” Winslow labeled him “an arrant knave,” and the nineteenth-century historian Charles Francis Adams said that Morton was “a born Bohemian and reckless libertine, without either morals or religion.”50 Whatever else he was, however, his ideas about life and, in particular, commerce in guns were too disturbing for Plymouth to accept without a fight.

Morton first visited America in 1622, then returned in 1625 with a captain Wollaston, a few other men of means, and “a great many” indentured servants who were obliged to work for Wollaston and the other overseers for a period of years, the goal being to set up fishing and fur-trading operations along the shores of Massachusetts Bay. This motley band settled Mt. Wollaston (now Quincy), but in less than a year Wollaston, whom Bradford called a “man of pretty parts,” had grown pessimistic about the future of such an outpost, and he particularly wanted to avoid having to suffer through another long, cold New England winter. So he took most of his servants to Virginia, leaving the rest of them, one of his associates, and Morton behind. Virginia was much more to Wollaston’s liking, and he soon sold his servants for a considerable profit, requesting that another contingent of them be delivered from Mt. Wollaston forthwith.51

This turn of events alarmed Morton, because he knew that soon Wollaston would be asking him to head south as well. Between his three-month visit in 1622, and his more prolonged stay in Mt. Wollaston, Morton had fallen unabashedly in love with New England and its commercial potential, and he wanted to settle there for good. In New English Canaan, published in 1637, Morton mused rhapsodically about this new land, which had captured his imagination in the same way it had John Smith’s years earlier. “And when I had more seriously considered, of the beauty of the place, with all her fair endowments,” wrote Morton, “I did not think that in all the known world it could be paralleled…. For in mine eye, ‘twas Nature’s Masterpiece, her chiefest magazine of all where lives her store: If this land be not rich, then is the whole world poor.”52

Instead of succumbing to Captain Wollaston’s entreaties to send more servants south, Morton began to sow dissension among those who had stayed behind, telling them that if they went south they too would be sold. At the same time he held out another option for their consideration. If they agreed to join with him and settle in this area, Morton promised to break their bonds of servitude, treat them as equals, and share with them the fruits of their labor. Such emoluments were sufficient to incite a mini-insurrection, during which Wollaston’s other associate was cast out, and Morton, or “Mine Host” as he later liked to be called, and his minion established a trading post that he christened “Mare-mount,” or literally “hill by the sea.” But the Pilgrims, who greatly distrusted Morton and his heathenish ways, referred to this settlement as “Merie-Mount,” which has come down to us as “Merrymount,” a most appropriate designation given what transpired there.53

Merrymount quickly became an unusually free and conspicuously rowdy community bent on having fun while making money. Morton established warm relations with the local Indians, viewing them more as friends and coconspirators than ignorant natives and potential enemies. Morton respected how the Indians honored their aged, and he admired their compassion, humor, joie de vivre, and willingness to share pretty much everything but their wives. He was further impressed that they had no jails or gallows “furnished with poor wretches.”54 Indeed, if Morton had had to choose between being among the Pilgrims at Plymouth or the Indians, he would have chosen the latter without question.

Using guns for barter, “Mine Host” and his followers soon were overseeing a thriving beaver-pelt trade with the Indians.55 In May 1627, to celebrate the success of his venture, Morton held a celebration for his men, the local Indians, and all other comers, replete with beer, poetry, dancing, and an eighty-foot maypole topped with the antlers of a large buck, which served, Morton said, “as a fair sea mark for directions; how to find out the way to mine Host of Ma-re Mount.” A sexually provocative song composed for the wild event implored, “Lasses in beaver coats come away, Yee shall be welcome to us night and day.” The song’s refrain was even bawdier:

Drink and be merry, merry, merry boys,

Let all your delight be in Hymen’s joys,

Lo to Hymen now the day is come,

About the merry Maypole take a Room.56

The priggish and straitlaced Puritans of the Plymouth Colony viewed these proceedings with growing horror. Commenting on the situation at Merrymount, Bradford claimed that Morton and his men

Fell to great licentiousness and led a dissolute life, powering out themselves into all profaneness. And Morton became lord of misrule, and maintained (as it were) a school of Atheism. And after they had got some good into their hands, and got much by trading with ye Indians, they spent it as vainly, in quaffing & drinking both wine & strong waters in great excess, and, as some reported, ten pounds worth in a morning. They also set up a Maypole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women, for their consorts, dancing and frisking together, (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices. As if they had anew revived & celebrated the feasts of the Roman Goddess Flora, or the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians.57

The colonists were also bothered by Merrymount’s commercial success. Each beaver that went to Morton and his men was one less that could potentially have gone to Plymouth, and Plymouth’s leaders hated being undercut in the trade that was literally keeping them afloat. But much more worrisome to the Plymouth Colony than either Merrymount’s “great licentiousness” or its profit was Morton’s supplying the Indians with guns and teaching them how to shoot. Had his only offense been outcompeting Plymouth in trade or sinking to the depths of moral depravity, at least in the eyes of the Puritans, Morton likely would have been left to his own devices, while still being roundly cursed by his neighbors.58 But with the trade in guns Morton had crossed the line and set the stage for his ultimate downfall.59

It didn’t matter that the Indians had shown no inclination to turn their guns on the English but had used them primarily for hunting—the Pilgrims’ fear of what might happen was enough cause for alarm. Bradford wrote of the “terror” felt by the settlers living “straglingly” along the coast, with “no strength in any place,” who met gun-toting Indians in the woods. If Morton was not stopped, the argument ran, the arming of the Indians would only escalate. And by early 1628 all signs indicated that such an escalation was already taking place. Morton had requested that more “pieces” be sent over from England, and the Indians had, according to Bradford, become “mad” to get guns, and would give anything they owned to attain them, “accounting their bows & arrows but baubles in comparison.”60

In the spring of 1628 representatives of all the plantations in the vicinity of Boston Harbor that felt most threatened by Morton met to consider their options. Realizing that none of them had the power to confront Morton on their own, or even as a combined force, they turned to Plymouth for support. As the most populous and powerful settlement in the area, and the one that potentially had the most to lose from the actions of Morton and his row-dies, Plymouth rose to the challenge. Persuasion was chosen as the first line of attack, and the aggrieved plantations wrote to Morton “in a friendly & neighborly way,” imploring him to stop trading guns to the Indians. Morton responded with a scathing letter, inquiring by what right the plantations questioned his activities, and claiming that he would continue to “trade pieces with the Indians” despite the displeasure it had aroused. Holding out hope that Morton was amenable to reason, the plantations sent a second joint letter, in which they advised Morton to be “more temperate in his terms,” and pointed out that he was violating King James’s 1622 ban on trading guns with Indians. They also added a subtle warning, telling Morton that “the country could not bear the injury he did.”

Morton’s response was anything but subtle, declaring “the king was dead and his displeasure with him.” Then he threw in a warning of his own. If anyone tried to “molest” him, it was they who should be worried: He would be ready for them.61 This insolence was too much for the plantations to tolerate, and they decided to take Morton by force. With each of the plantations contributing money to a battle fund, Plymouth outfitted Miles Standish and eight men, and sent them to apprehend “the lord of misrule.”

What transpired next depends on who is doing the telling. According to Morton, whose account is filled with characteristic braggadocio, “the Separatists envying the prosperity and hope of the plantation at Mare Mount,” particularly its success with the beaver trade, “made up a party” to capture him, claiming that he was “a great monster.” Morton made light of the force sent against him, calling them the “nine Worthies of New Canaan,” and derisively labeling Standish, who was small in stature, as “Captain Shrimp.” Morton claimed that Standish and his men caught him “by accident” at Wessagussettt, a mile or so from Merrymount, and that they were so joyous to have “obtained” their “great prize” that they “fell to tippling” and gorging themselves on food. Morton did not partake in the festivities, so he could remain alert, and escape if the opportunity presented itself.

That night, when the six men guarding him, including one who was lying beside him in bed, drifted into a deep sleep, Morton arose and made his way silently through two locked doors. But just as he thought he had escaped unnoticed, the second door slipped from his grip and slammed shut. This woke the guards and Standish, who Morton claimed, “took on most furiously, and tore at his clothes for anger, to see the empty nest, and their bird gone.”

Standish caught up with Morton at Merrymount and pleaded with him to surrender and lay down his arms, so that he could be sent back to England. Morton, who claimed to be “the son of a soldier,” at first declined, but after thinking of all the “worthy blood”—not his, theirs—that would be spilled in a fight, he relented when Standish promised not to harm him or any of his men. Despite this agreement Morton claimed that when he opened the door, “Captain Shrimp” and his men “fell upon him, as if they would have eaten him,” and that the only reason they didn’t “slice” him with a sword was because one of Standish’s men, an old soldier, admonished the “worthies for their unworthy practices.”62

Bradford’s account lacks both the drama and the indignation of Morton’s version. There is no mention of the encounter and stealthy escape at Wessagussett. Instead, when Standish arrived at Merrymount, “mine host” was already holed up in one of his houses, the doors and windows barred, with his men about him and “diverse dishes of powder & bullets ready on the table.” Morton at first ignored Standish’s summons to yield, preferring to cast “scoffs and scorns” at his attackers. Then, fearing that Standish would break down the walls of the house, Morton and some of his men exited through the front door, guns by their side. But they were all “so steeled with drink” that they couldn’t even raise their “pieces” to aim, much less shoot any of the force arrayed against them. Morton wanted to shoot Standish, but before he could make an attempt, Standish stepped forward, grabbed the gun, and took hold of Morton. So ended the Battle of Merrymount, the only casualty one of Morton’s men, who was so drunk that “he ran his own nose upon the point of a sword” one of Standish’s men was holding up as he entered the house.63

Whichever of these stories is more accurate, the end result was the same. Morton received a mock trial and was held prisoner on the rocky Isle of Shoals, ten miles off the coast of New Hampshire and Maine, until a ship was found to take him back to England. Stripped of its leader, Merrymount dissolved and was renamed Mount Dagon in 1629, only to burn to the ground the next year.64

WHILE THE PLYMOUTH COLONISTS DEALT WITH MORTON, they simultaneously developed an interesting relationship with the Dutch. It began in March 1627, when Isaack de Rasière, the secretary of New Amsterdam, wrote governor Bradford a letter. Although the Dutch had known about the Plymouth Colony since its inception, this letter was the first formal contact between the two. De Rasière noted that the Dutch had often traveled by shallop up the coast and traded with Indians within a half day’s journey of Plymouth, and being in such close proximity, the Dutch thought it was time to introduce themselves formally. De Rasière congratulated the English on the success of their colony and held out the hand of friendship. In particular he wanted to establish a mutually beneficial trading arrangement with Plymouth, and therefore offered to sell them Dutch wares in exchange for beaver or otter skins, and he added that if the English didn’t desire these things, he hoped they would nonetheless be willing to sell the Dutch furs and other useful items “for ready money.”65

Bradford responded with similar politesse, affirming Plymouth’s desire to trade, but he also warned the Dutch to stop trading with the Indians to the southwest of Cape Cod, in and around Buzzard’s and Narragansett bays. That land, he maintained, was claimed by England, a fact that gave Plymouth the right to expel intruders—a right Bradford implied they would exercise if the Dutch didn’t back off. De Rasière responded that the Dutch had a claim to that land as well, and would continue to trade with the Indians as they pleased, but for the time being neither side took this dispute any farther. Instead they began trading.

With trumpets blaring to announce his arrival, de Rasière visited Plymouth in October 1627. He laid out for the colonists’ perusal a great range of items, including tobacco, three types of colorful cloth, and sugar. The most important thing de Rasière brought with him, however, was wampum. Largely ignorant of wampum’s great value in the Indian trade, the Plymouth colonists listened intently as he told them “how vendible it was” at Fort Orange, and how it had enabled the Dutch to obtain a great many furs. Then, in a not-so-subtle effort to direct Plymouth’s trading attention to the northeast and away from southwestern areas where the Dutch were most active, de Rasière said that there was no doubt that if the English acquired wampum it would be a great boon to their fur trade in Maine, along the Kennebec River. Convinced by this pitch, Plymouth’s leaders purchased fifty pounds’ worth of the shell beads.66

The purchase of wampum and the focus on Maine meshed perfectly with Plymouth’s evolving plans for the fur trade. After Winslow’s successful trip to Maine in 1625, which yielded seven hundred pounds of beaver, there had been others to the same general vicinity. To get this trade on a firmer footing, Plymouth obtained a patent to the land along the Kennebec in 1628, and that same year they established a trading house on the river, at the site of present-day Augusta, and stocked it with clothing, blankets, corn and other food-stuffs, as well as other commodities that the Indians had shown a willingness to trade for furs. The colonists also stocked the post with the wampum they had recently purchased, but to their dismay found that it wasn’t as “vendible” in Maine as de Rasière had predicted, at least in the short term. The inland Indians who came to the new trading post were unfamiliar with wampum and were at first reluctant to accept it in trade. Within two years time, however, that reluctance had been replaced by desire, with Bradford noting that from then on the Indians “could scarce ever get enough” wampum.67

THE ACQUISITION OF WAMPUM AND THE EXPANSION OF TRADING activities in Maine coincided with a radical restructuring of the economic underpinnings of the Plymouth Colony. In 1628 eight of the leading men in the community, including Bradford, Winslow, and Standish, assumed the burden of paying off the colony’s £1,800 debt to the Merchant Adventurers in return for a six year monopoly to the region’s fur trade. With Isaac Allerton, the former assistant governor of the Plymouth Colony, as their lead sales agent in London, the eight so-called undertakers expected to export a steady stream of furs and quickly draw down the debt, and they got off to a good start, sending nearly £700 worth of beaver to England their first year.68

The undertakers’ stake in Maine’s fur trade increased in 1629 when Allerton and a few other investors came to them with a proposition. Allerton’s group had decided to launch a fur-trading post on the Penobscot River, and they wanted the undertakers to join as partners in this venture and/or supply the post with trading goods and food. This offer placed the undertakers in an uncomfortable position. If they refused to join the venture or supply the post, they risked offending and possibly losing the support of Allerton’s group, which included the undertakers’ main financial backers. On the other hand, if the undertakers didn’t become partners in the Penobscot post but provided it with supplies, they would be aiding the competition, and likely reducing the profitability of the fur-trading post they had set up on the Kennebec River just a year earlier.

Making the decision more problematic was the undertakers’ distrust and dislike of the man chosen to run the Penobscot post—Edward Ashley—“a very profane young man,” according to Bradford, who had earlier offended the Pilgrims’ sensitivities by living with the Indians, going “naked among them,” and adopting “their manners.” In the end the undertakers overlooked their concerns about Ashley, and signed on as partners and suppliers. It wasn’t long, however, before Ashley lived up to their worst fears. Although he quickly gathered a “good parcel of beaver,” Ashley refused to pay back the undertakers for any of the supplies they had given him, and then he had the gall to ask for more. And Ashley’s familiarity with the Indians had, Bradford claimed, led him to commit “uncleanness with Indian women,” an unpardonable sin in the Pilgrims’ eyes. But what got Ashley into the most trouble was his trading “powder and shot” with the Indians, an offense that led to his arrest and imprisonment in England. With Ashley out of the way, the undertakers took over operations at the Penobscot trading post in 1630.69

JUST FOUR YEARS AFTER THE PILGRIM’S COLONIAL EXPERIMENT had begun, Edward Winslow wrote glowingly about the promise of the fur trade in New England. “Much might be spoken of the benefit that may come to such as shall plant here, by trade with the Indians for furs,…[for] the English, Dutch and French return yearly many thousand pounds profit by trade only.”70 During the balance of the 1620s Winslow and his fellow colonists made good on that promise. The Plymouth Colony had solidified its presence in the fur-rich region of Maine, and despite Dutch designs, was also branching out toward the southwest, establishing another trading post on the underside of Cape Cod, at the head of Buzzard’s Bay, on the site of modern Sandwich. The combination of surplus corn harvests, wampum, and other commodities now coming more regularly from England gave Plymouth the means to expand the fur trade, while the colony’s new financial arrangement and the undertakers’ monopoly allowed for visions of a debt-free future. Indeed, by the dawn of the 1630s all the signs seemed to be pointing to the colony’s continued success in the fur trade. Yet within ten years that trade simply disappeared.