—7—

Adieu to the French

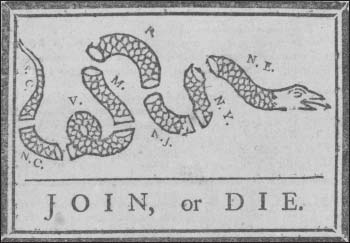

Benjamin Franklin’s warning to the British colonies in America, printed in 1754, exhorting them to unite, or “Join,” against the French and the Indians, or “Die.” This is widely believed to be America’s first political cartoon.

WHILE THE ENGLISH, THE DUTCH, AND THE SWEDES WERE battling over the fur trade to the south, to the north the French were struggling to keep their dreams of a fur-based empire alive. From the early 1630s to the early 1660s French merchants and traders veered between optimism and pessimism as New France’s fur trade gyrated wildly between great success and utter failure. Things started off encouragingly. In 1633 Samuel de Champlain, the “Father of New France,” returned to Quebec as acting governor, with the revitalization of the fur trade as one of his primary goals.1 But he realized he had a problem. Many decades of hunting in the drainage area of the lower St. Lawrence River had depleted local populations of beaver and other fur-bearing animals. Champlain believed that for the fur trade to thrive New France needed to expand its horizons. From their traditional allies and trading partners the Huron and the Algonquin, the French had heard about the “People of the Sea,” whose lands were far to the west and full of beaver. Champlain wanted to contact these mysterious people not only because of the furs they could provide but also because he thought they lived on the edge of the western ocean (the Pacific) and could be Asian. At long last dreams of a Northwest Passage to the Orient might be realized. To head this mission Champlain chose his trusted interpreter, Jean Nicollet.2

Nicollet, who first arrived in New France in 1619 when he was about twenty, had become one of Champlain’s truchements—young men or boys sent out to live among the Indians, learn their language and ways, build stronger ties between the French and the Indians, and encourage the latter to engage in the fur trade. Nicollet spent most of the next fourteen years among the Nipissing, an Algonquian people in the region northeast of Lake Huron, and thus was well suited for the trip Champlain had envisioned. Departing from Quebec in July 1634 and meeting seven Huron escorts along the way, Nicollet proceeded through areas never before seen by Europeans. They canoed through the Straits of Mackinac into Lake Michigan, ending up on the shores of Green Bay at the northeastern boundary between Michigan and Wisconsin.

Nicollet stayed briefly with the Menominee, while he sent one of his Indian companions on a journey south to tell the People of the Sea that he was on his way. They were so thrilled that Manitouiriniou (Wonderful Man) was coming to visit that they sent a party to escort him to their village and carry his bags. Still thinking that he might soon be meeting Asians, Nicollet donned “a grand robe of China damask, all strewn with flowers and birds of many colors” to make a good first impression. When Nicollet strode into the village thus attired and gripping two pistols, “the women and children fled at the sight of a man who carried thunder in both hands.” Of course Nicollet was nowhere near Asia, and the People of the Sea turned out to be the Winnebago living near the mouth of the Fox River. Word of Nicollet’s arrival quickly spread throughout the region, and soon four to five thousand Indians arrived to welcome him, with various chiefs hosting banquets in his honor, one of which served 120 roasted beavers. Nicollet concluded peace treaties with the local tribes, and not long after furs from these western lands began streaming into New France.3

In the fall of 1635 Champlain suffered a serious stroke. Paralysis, beginning in his legs, soon spread to his arms. For ten weeks he remained bedridden, but his mind was still sharp. He spent much of this time preparing “a general confession of his entire life,” which he gave to his dear friend the Jesuit priest Charles Lalement. Finally, on Christmas Day 1635, Champlain drew his last breath. All the people of Quebec, along with the many of the Indians he had befriended over the years, turned out for a procession in his honor, followed by his burial at the Church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Recouvrance, to which Champlain had bequeathed much of his worldly possessions.4

DESPITE CHAMPLAIN’S HOPES THAT NEW FRANCE WOULD become a functioning, multidimensional colony, it remained little more than a fur-trading outpost with major hubs at Quebec, Montreal, and Trois-Rivières. Even the farmers who came to till the land, and the Jesuit missionaries who came to Christianize the Indians, got swept up in the trade, enticed by the lure of quick profits.

The furs of New France traveled two main routes to market. Men working for the fur-trade monopolies granted by the king waited at their posts for the Indians to arrive in canoes laden with furs brought from the backcountry, whereupon the trading began. Then there were the coureurs de bois (runners of the woods), who, like their Dutch counterparts, the boschlopers, were self-employed and went to where the furs were and traded directly with the Indians, often becoming the first Europeans the Indians had ever seen, unwitting ambassadors of Western civilization.

Using the vast and spidery network of streams, rivers, and lakes, the coureurs de bois cut a serpentine path through the landscape of North America. Their main form of transportation was the graceful tapered, cedar-ribbed birchbark canoe, used by the Indians of the north since time immemorial for traveling, hunting, and fighting. This beautifully balanced workhorse, with its neatly stitched skin and seams made watertight with sticky pine gum, was stable and sturdy enough to hold hundreds if not thousands of pounds of people and pelts, yet light enough to be portaged with relative ease. Flat-bottomed and buoyant, and skillfully propelled and maneuvered by powerful sweeps of the broad flat paddles, the birchbark canoe was as serviceable in deep, fast-flowing rivers as it was in shallow, sluggish streams. Made of materials readily available throughout the woods, it could be easily repaired on the fly. So central was the birchbark canoe to the growth of the northern fur trade that it is hard to imagine that trade having succeeded without it.5

The coureur de bois, observed the author Bernard DeVoto, was “an Indian with a white man’s mind and he lived free…pulled the wilderness round [himself]…like a robe…[and] wore its beauty like a crest.”6 Away for weeks, months, and even years at a time, the coureurs de bois were always bold, often reckless and crude, and expert woodsmen who lived and hunted with the Indians. They were shrewd businessmen, knew how to acquire the best pelts, and loved to have a good time, with raucous singing, dancing, gambling, drinking, and sex being the usual forms of entertainment.7 They were freelancers par excellence who sold their furs at the French trading posts but did not hesitate to traffic with the Dutch and the English if the price was right.

To some the life of the coureurs de bois verged on the idyllic. As one historian wrote, “They were the most romantic and poetic characters ever known in American frontier life. Their every movement attracts the rosiest coloring of imagination…. We catch afar off the thrilling cadences of their choruses, floating over prairie and marsh, echoing from forest and hill,…What a rollicking life was this!”8 Contemporary critics offered harsher assessments. Although the Jesuits usually relied on the coureurs de bois to lead them into the wilderness to set up missions and to trade on their behalf, they still railed against the coureurs de bois’ heathenish behavior. The Jesuits were appalled by their liberal use of liquor for personal inebriation and as a means to obtain furs, and they were horrified by their propensity to “go native”—consorting too closely with the Indians, dressing like them, and even taking Indian women as wives. Government officials were frustrated by their unwillingness to settle down and contribute to the growth, permanence, and social fabric of the colony. And the fur-trade monopolies often viewed them as competitors or, worse, turncoats willing to sell their furs to the highest bidder regardless of nationality. Whether seen as romantics, reprobates, rootless wanderers, or simply unwelcome competition, the coureurs de bois remained critically important to the fur trade of New France as long as it lasted.9

AFTER MANY WILD FLUCTUATIONS NEW FRANCE’S FUR trade recorded its best year ever in 1646, shipping out 168 casks, or more than 33,000 pounds, of pelts, predominantly beaver.10 But growing violence in the wilderness overshadowed this success. The Iroquois were viciously attacking New France’s Indian allies, including its main trading partner, the Huron. As an entry in the Jesuit Relations from 1642 relates, “When our Hurons” paddle their canoes to Trois-Rivières or to Quebec to trade their beaver skins, they are less afraid of the turbulent rapids and the precipitous falls they must run, “on which they are frequently wrecked,” than they are of the Indians who lurk in the woods. “For every year the Iroquois prepare new ambushes for them, and, if they take them alive, they wreak on them all the cruelty of their tortures.”11

The attacks were part of a broader conflict called the Beaver Wars, so named because historians originally believed that they were motivated primarily by the Iroquois’ need to find new sources of beaver—a need that was created because the beaver populations on the Iroquois land had been devastated by years of hunting. If the Iroquois wanted to continue their economically beneficial fur-trading relationship with the Dutch, they had to find new sources of furs. Inevitably they chose to do so by attacking other Indians and taking the furs they had gathered as well as appropriating their lands.12 More recent and persuasive scholarship on the Beaver Wars, however, downplays the role of economics and the fur trade. From this perspective the Iroquois’s attacks are seen more in the context of mourning wars, which were a traditional means of rebuilding a tribe’s strength after many of its members had been killed or died. During the 1630s and early 1640s, a series of smallpox epidemics, likely introduced by fur traders, ripped through the Iroquois nation, cutting its population in half. In mourning for these dead, women demanded that their men raid other tribes to capture replacements for those who had been killed, thereby replenishing the Iroquois’ ranks. And in the Beaver Wars that followed the Iroquois tried to do just that.13

Whether the Beaver Wars were motivated by economics or mourning, or both, the results were the same. By 1649 the Iroquois had virtually destroyed the Hurons, dispersed its survivors to the west, and in the process brought New France’s fur trade to its knees. In subsequent years the range of the Beaver Wars expanded as the Iroquois attacked other Indians, including the Ottawa, the Algonquin, the Petun, the Erie, and the Neutral, further crippling the French-Indian trade.14 The destructive toll of these wars was captured by an entry in the Jesuit Relations of 1653. “Never were there more beavers in our lakes and rivers, but never have there been fewer seen in the warehouses of the country. Before the devastation of the Huron, a hundred canoes used to come to trade, all laden with beaver-skins; the Algonquians brought them from all directions;…The Iroquois war dried up all these springs. The beavers are left in peace and in the place of their repose…[The Iroquois] are preventing all the trade in beaver skins, which have always been the chief wealth of this country.”15 The dislocation wrought by the Beaver Wars was so bad that by the time the English took over New Netherland from the Dutch, in 1664, New France’s fur trade was for all intents and purposes “dead”—although only temporarily.16

NEW FRANCE’S FUR TRADE EMERGED WITH RESTORED vigor between the mid-1660s and the late 1680s. Part of the reason for this resurgence, ironically, can be traced to the Beaver Wars, which were slowly coming to an end. As the Indians displaced by the Iroquois traveled west, north, and south to the shores of Lakes Michigan and Superior, they met tribes unfamiliar with the fur trade, including the Sioux, Miami, Cree, Fox, and Illinois. These tribes were enamored of the European wares owned by the displaced Indians, and a new trade was born. The Ottawa, whose name literally translates as “traders,” exchanged their worn knives, kettles, and cloth for fine beaver robes and pelts provided by the distant tribes, and then took those furs to Montreal, where they were exchanged for European goods, which were in turn used to obtain more furs. Thus the Ottawa became middlemen in a thriving trade, and as the historian Harold A. Innis put it, “The Miamis and the Sioux ceased roasting the beaver for food, and began a search for skins.”17

Exploration was another reason for the revival of New France’s fur trade. Frenchmen whose names now dot America’s landscape ventured west and south to claim new lands, establish trading ties with local Indians, and find a water route to the western ocean.18 Among the first to set out were the Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette and the fur trader Louis Joliet. Lured by tales of a great river—which the Indians called the Meschacebe, or the “Father of Waters”—to the south of the Great Lakes, Marquette and Joliet launched an expedition in the spring of 1673 to see if the tales were true, and to discover into which body of water this great river emptied. With five Indian guides they journeyed in birchbark canoes to Green Bay, ascended the Fox River, portaged to the Wisconsin, and proceeded to its terminus, where they found the Father of Waters, which would later be called the Mississippi.

Although Marquette and Joliet were not the first Europeans to see the Mississippi—that distinction goes to Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto who came upon the river in 1541, near modern-day Memphis, Tennessee—they were the first to map and explore it. Floating downriver, Marquette and Joliet encountered friendly Indians, dined on buffalo, which were plentiful along the riverbanks, and passed the mouths of the Missouri and Ohio rivers. Running low on supplies and convinced that the Mississippi exited in the Gulf of Mexico, and not on the shores of a western ocean or the Atlantic (as some had believed), Marquette and Joliet turned around near the mouth of the Arkansas River and headed back to New France to share the news of their discovery.19

René Robert Cavelier de La Salle went Marquette and Joliet one better. In 1682, after many years exploring the Great Lakes region and establishing a series of fur-trading posts, La Salle journeyed down the Mississippi all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. With a flourish, and amid the firing of muskets, La Salle planted a flagpole, raised the royal arms, and claimed the river, and all the lands drained by it and its tributaries, in the name of King Louis XIV. And to honor the king La Salle called the new territory, which one of his party said was “the most beautiful country in the world,” Louisiana.20 While La Salle was traveling south, another Frenchman, Daniel Greysolon, sieur Duluth (originally “Dulhur”), went in the opposite direction, exploring the headwaters of the Mississippi, the shores of Lake Superior, and lands farther north. Along the way Duluth established posts and traded for furs with the Cree and Sioux, earning him the title “king of the coureurs de bois.”21

The discoveries of Marquette, Joliet, La Salle, Duluth, and other less celebrated explorers opened the way for the expansion of New France’s fur-trading empire, stretching from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Great Lakes region and down to the Gulf of Mexico. New France sent a flood of pelts back to Europe, restoring Paris’s preeminence in the production of fashionable furs and hats.22 Despite this success, New France remained nervous. It had good reason to be, since the English to the north and south threatened its plans for further imperial expansion and, more important, its control of the lucrative fur trade.

NEW FRANCE LIKELY WOULDN’T HAVE HAD A PROBLEM with the English to the north if only the French had treated Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart, sieur des Groseilliers, better. While the Beaver Wars were still raging, Radisson and Groseilliers were among the very few coureurs de bois brave enough to pursue their trade and risk being attacked by the Iroquois. When they returned in the late 1650s from an expedition to the Great Lakes with sixty canoes full of pelts, they provided one of the only bright spots in an otherwise dismal time for New France’s fur trade.23 Buoyed by their success Radisson and Groseilliers asked the governor for permission to launch another expedition, which was given, but with so many conditions that the adventurers could not accept them, instead departing on their own terms though the governor expressly forbade them from doing so. Although this expedition was as successful as its predecessor, it had a different outcome. By the time they returned to Quebec in 1663, a new governor was in charge, who decided to enforce the laws intended to clamp down on coureurs de bois for trading without licenses. As a result Radisson and Groseilliers were briefly imprisoned, heavily fined, and forced to hand over most of their furs.

Incensed by such treatment Radisson and Groseilliers journeyed to France and pleaded their case before the king—to no avail. While in Paris they told anyone who would listen about a great body of water (Hudson Bay) far to the north of the Great Lakes that the Indians had spoken of. It was ringed by great rivers populated by an enormous store of fat beavers with luxuriant pelts. If they could only get backing for a northern expedition, Radisson and Groseilliers argued, this rich hunting ground could be claimed for France. But nobody was interested in their plan, either in Paris or back in Quebec, so Radisson and Groseilliers, still committed to their idea, took the only action they felt was left open to them—they set their sights on getting English support.24

Radisson and Groseilliers made their way to Boston, where, after a few failed attempts to launch an expedition to Hudson Bay, they met with Sir George Cartwright, vice chamberlain to the king and treasurer of the navy. Intrigued by the Frenchmen’s plans, he offered to arrange an audience with King Charles II. Off to London they went, arriving in the fall of 1665 only to find the city in the throes of the bubonic plague that had killed nearly ninety thousand people. Enveloped in the stench of the dead and dying, Cartwright, Radisson, and Groseilliers proceeded by boat up the Thames to their meeting with King Charles, a royal with an insatiable appetite for money, who saw in Hudson Bay an opportunity for great financial gain, and a way of obtaining a competitive edge over the French in the race for North America’s furs. He gave Radisson and Groseilliers a weekly allowance of forty shillings and promised that soon they would have a ship to pursue their commercial venture.25

Eventually the task of getting the project off the ground was given to the king’s cousin Prince Rupert, a dynamo of a man who was already a successful entrepreneur, accomplished artist, celebrated soldier, and noted inventor (who could claim, among other things, to have developed the first torpedo, built a diving bell to retrieve sunken treasure, and introduced the Italian engraving method known as mezzotint to England). Rupert gathered together a company of adventurers whose deep-pocketed subscribers financed a trip to Hudson bay in 1668, which returned the following year with a profitable cargo of beaver and other furs, thereby proving the feasibility of Radisson’s and Groseilliers’ plan. This was enough to spur further investments in the company, but Rupert’s goal was grander than that. He knew that to secure his claim to the Hudson Bay trade he needed a royal monopoly, and on May 2, 1670, he got what he wanted, and then some. With his signature Charles II made Rupert and his partners the “true lords and proprietors” not of only Hudson Bay but also all of the lands whose waters drained into it. This extraordinary real estate transaction, one of the largest in history, gave the newly created Hudson’s Bay Company claim to 1.5 million square miles that became known as Rupert’s Land, and that encompassed roughly 40 percent of present-day Canada and significant pieces of Minnesota and North Dakota.26

By turning its back on Radisson and Groseilliers, New France had fostered the creation of a new and potentially powerful competitor. Indeed the Hudson’s Bay Company quickly became a source of great irritation to New France, since the furs they normally received from the Indians were now siphoned off by the company’s posts ringing the bay.27 The upstarts to the north, however, weren’t the only Englishmen who kept New France on edge. To the south lay a string of English colonies, also impinging on New France’s expanding fur trade.

NEW FRANCE’S BIGGEST COMPETITOR WAS THE NEWLY CREATED English colony of New York. With the expulsion of the Dutch in 1664, Fort Orange became Albany, but this hardly changed the commercial character of the old trading post. Many of the Dutch who had made Fort Orange the hub of the North American fur trade remained once the English had taken over. They now swore their allegiance to England’s king and continued to profit. The Iroquois, who had long traded with the Dutch, were quick to notice the shifting direction of the winds, and transferred their loyalty to the English. With the Iroquois acting as middlemen for various tribes, bartering English goods for pelts, furs that might otherwise have ended up in New France kept on coming down the Hudson to Albany.

The southern colonies, too, in particular Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the Carolinas, were another threat to New France’s fur trade. Capitalizing on the abundance of deer in the region, southern colonists established connections with local Indians and built up a vast trade in deerskins, which were sent to Europe to be processed into shoes, gloves, and other leather goods.28 The southern colonies also pursued a more traditional fur trade that focused on beavers, raccoons, wolves, muskrat, mink, and black bears, among other animals, but it was far smaller and less economically significant than the deerskin trade.* As the populations of animals along the coast dwindled, southern traders traveled farther inland, ultimately making their way across the Appalachians, bringing them into competition with the French.

Ironically New England, where the English fur trade had begun, was no longer a factor in the growing competition for furs in eastern North America. By the mid-to-late 1600s, and earlier along the coast, the New England colonies, had, with the help of the Indians, run the fur trade into the ground.29

There simply weren’t enough fur-bearing animals left in New England’s woods to generate decent profits, and New Englanders’ access to furs was limited by competition from other traders and a lack of good water routes to the interior.30 Even if the New England colonies had wanted to push their trading operations west, they couldn’t have, effectively blocked by the huge and rapidly expanding colony of New York.

Although New England’s fur trade would continue to sputter along, it was not a force to be reckoned with, nor one that caused New France any concern. And as many historians have pointed out, the withering of New England’s fur trade shifted the dynamics for many of the region’s Indians, who had depended on that trade as their source for European goods. Without furs to barter the Indians were, as Cronon notes, compelled to “turn to the only major commodity they had left [to trade]: their land.”31 Thus, as the furs disappeared, so too did the Indians’ land, piece by piece—a shift that created stresses that fueled regional conflict between the Indians and the English.

The result of all the fur-trading activity along the eastern half of the continent was that by the late 1680s a nearly three-thousand-mile battle line had been drawn from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Gulf Coast, with the French and the English on opposite sides. From that point until the middle of the next century, the fur trade would remain a constant source of tension between the two powers, and one that would contribute significantly to the expulsion of the French from the continent during the French and Indian War.

THE FRENCH AND THE ENGLISH HAD BEEN ON A COLLISION course in America since 1611, when an English vessel trading for furs near the Kennebec River captured a French trading vessel, claiming that the latter was trespassing on English territory. The only thing that had really changed by the end of the century was the geographical extent of the conflict. La Salle realized this in 1684, when he urged the French to build on his discoveries and colonize and defend Louisiana before it was too late. “If foreigners anticipate us,” wrote La Salle, “they will…complete the ruin of New France, which they already hem in through Virginia, Pennsylvania, New England and the Hudson’s Bay.”32 The English, too, knew that bold action was needed to outflank the French, evidence of which can be gleaned from a memorial written by a group of Englishmen around 1690 asking for a patent that would give them control over the lands to the west of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, all the way to the Pacific coast. “The English by settling [these lands]…may without any difficulty perfectly destroy the French commerce with the Indians and secure the [fur] trade wholly to themselves.”33 With the French and the English eyeing lands and opportunities the other had claimed as their own, the question was not if they would come to blows, but when.

The first two such confrontations were King William’s War (1689–97) and Queen Anne’s War (1702–13). Both of these were offshoots of European wars that preceded them, with the War of the Grand Alliance in Europe giving rise to the former and the War of the Spanish Succession leading to the latter. Although the European wars had nothing to do with the fur trade, when they spilled over to America, control of the fur trade became one of the strategic goals, with the French, the English, and their Indian allies jockeying for advantage. The net result was a wash, however, since virtually all the gains achieved on the ground were relinquished at the negotiating tables.34

The Treaty of Utrecht, which ended Queen Anne’s War, ushered in a thirty-one-year period of relative peace between the English and French. At the conclusion of the war New France’s fur trade lay in ruins. The troubles began in the late 1600s, when French explorers expanded New France’s geographical reach, and traders flooded the new lands, returning with canoes overflowing with furs. These traders included the ubiquitous coureurs de bois as well as a newer breed, the voyageurs, who were essentially highly skilled paddles for hire, employed by merchants to travel into the backcountry to trade with the Indians.35 For a while the coureurs de bois and voyageurs were able to earn rich rewards for their efforts because French furriers and hat makers could use all the furs they could get.

But the wars put a damper on the trade. The French people, heavily taxed to fund the wars, had little money left over for furs. And because France was at war with so many European countries, its access to many of its traditional markets was cut off. As a result the demand for French furs dropped precipitously. Yet the traders still ventured forth and were as productive as ever, and soon the supply of furs far outstripped what the market could bear. By the late 1690s the furs collected annually in New France were four times what was needed in France, and the price for pelts plummeted. The king clamped down on the coureurs de bois and closed western fur trading posts to try to reverse the trend, but the pelts continued to arrive. Excess furs piled up in warehouses, where many of them rotted or were eaten by rats. Small mountains of furs were burned to help reduce the supply, enveloping Montreal in thick black plumes of acrid smoke, which could be seen and smelled for miles around.36

By the time the Treaty of Utrecht was signed, most of New France’s stockpile of furs had been sold, burned, or become so riddled with holes as to be useless. King Louis XIV and the leaders of New France, convinced that furs were the colony’s economic lifeline to the future, reinvigorated the trade. Restrictions on coureurs de bois were lifted, and they were encouraged to gather as many pelts as quickly as they could. Forts and trading posts were strengthened, reestablished, or created anew to protect and extend the fur trade in the Great Lakes region and along the Mississippi and its tributaries. And the increasing number of furs supplied by New France quickly found receptive markets overseas.37

MEAN WHILE THE BRITISH PURSUED A SIMILAR COURSE. After the war Britain enjoyed great prosperity. An upsurge in the demand for beaver hats and furs kept the traders at Hudson Bay and in the American colonies busy. Charleston, South Carolina, became a trading entrepôt. By the 1730s it was annually sending more than two hundred thousand deerskins and many furs to Britain, a veritable flood that generated “more wealth in the colony than indigo, cattle, hogs, lumber, and naval stores combined,” leaving rice as the only product in the colony more lucrative than furs.38 Augusta and Savannah, Georgia, and Columbia, South Carolina, which were started as trading posts, prospered accordingly. Virginia consistently exported around twenty thousand furs, using the taxes levied on such exports to support the College of William and Mary.39 And during most of the first half of the eighteenth century roughly 20 percent of the value of New York’s shipments to Britain came from the sale of furs, creating a new aristocracy of rich New Yorkers. It wasn’t just demand from Britain, however, that stimulated the fur trade. A growing hatmaking industry in the colonies, as well as increased colonial consumption of hats, added to the British fur traders’ incentive to produce.40

The colonies often competed for control of the fur trade, at times violently.41 But no matter how hostile the colonies were toward one another, they were united against the French. Although Great Britain and France were technically at peace, their American satellites were constantly in conflict along shifting borders extending from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.42 Both sides forged military and trading alliances with the Indians and often encouraged their allies to attack the competition, with the fur traders occasionally participating in the assaults. And as the English and French did their best to encourage the Indians to trade only with them, the Indians played the “French off against the English, using the fur trade as an instrument of their own foreign policy.”43

In this struggle for furs the British had key advantages, the most important of which were the quality, quantity, and price of their goods. British cloth, kettles, knives, guns, and the like were not only more abundant and in many instances superior to their French counterparts, but also much cheaper, in large part because of heavy taxes the French placed on the fur trade and the higher cost of transporting goods from France.44 With alcohol, too, the British outcompeted the French, since Indians preferred the more potent British West Indian rum—which they soon began calling “English milk”—to the relatively weak though better-tasting French brandy.45 Regardless of which “spirituous” drinks were employed, however, the devastating impacts were the same, leading some Indians to call for a halt to the use of firewater altogether.46 In 1753 Iroquois chief Scarrooyady lodged a complaint with the governor of Pennsylvania that could easily have been made ten, twenty, or thirty years earlier:

The Rum ruins us. We beg you would prevent its coming such quantities by regulating the Traders…. When these Whiskey Traders come, They bring thirty or forty kegs and put them down before us and make us drink, and get all the skins that should go to pay the debts we have contracted for goods bought of the fair traders; by this means we not only ruin ourselves but them too. These wicked whiskey sellers, when they have once got the Indians in liquor, make them sell their very clothes from their backs. In short, if this practice be continued, we must be inevitably ruined.47

As had been the case in the prior century, such pleas had little impact, and alcohol remained an integral and free-flowing part of the trade. Simply put, many Indians demanded alcohol as a part of the trade, and traders were more than willing to oblige.48

THAT THE FRENCH WERE ABLE TO MAINTAIN THEIR NORTH American fur trade in the face of British competition is a testament to many factors. French traders ventured farther in search of furs, tapping areas and tribes that lay outside the English sphere of activity and influence. French gunpowder was a draw since it was more plentiful, and perhaps the only French commodity of higher quality than the British. To undercut the English the French sometimes increased the amount they paid the Indians for pelts, to the point of eliminating profits or even selling at a loss. The French also often purchased trading goods from the British to improve their competitive stance. And knowing that they could get more money for their pelts from the British, French traders regularly flouted laws against smuggling and sold their furs at British trading posts.

The French also benefited from better overall relations with the Indians. Although neither the French nor the British viewed their Indian allies and trading partners as equals, the French generally treated the Indians, and their way of life, with more respect. This earned the French some measure of loyalty.49 They were more solicitous and extravagant in giving gifts to the Indians, and many coureurs de bois and voyageurs integrated themselves into Indian society, further strengthening economic ties. As one British colonist bitterly observed, the French traders “live and marry among them, in short are as one people which last is not commendable but gains their affection…but our nation is quite the reverse notion, and will be baffled out of this trade.”50

Perhaps the most important reason why the French traders looked good to the Indians is that so many British traders looked so bad. As the historian Charles Howard McIlwain wrote, “Most of these [British] traders were the very scum of the earth, and their treatment of the Indians was such as hardly to be suitable for description.”51 The governor of Pennsylvania observed in 1744, “I cannot but be apprehensive that the Indian trade, as it is now carried on, will involve us in some fatal quarrel with the Indians. Our traders, in defiance of the law, carry spirituous liquors among them, and take advantage of their inordinate appetite for it, to cheat them of their skins and their wampum…and often to debauch their wives into the bargain.”52 And Benjamin Franklin, that keen observer of human behavior, labeled British fur traders “the most vicious and abandoned wretches of our nation!”53 Of course French traders were hardly without faults. They also often plied Indians with liquor and abused them in various ways, just not as much as the English did.

Another reason why the French were often viewed more favorably by the Indians had to do with the differences between French and English colonization. New France was still more a glorified fur-trading post than a thriving colony. Altogether there were about sixty thousand Frenchmen in North America, concentrated in Canada and the Great Lakes regions and then spread rather thinly down to the Gulf of Mexico, shadowing the course of the Mississippi. Only a relatively small percentage of them were able to take up arms and defend the colony, making it incumbent upon the French to maintain good relationships with the Indians as a security precaution. The French were also less interested in settlement than they were in maintaining an active fur trade. The main goal, therefore, was to limit the French footprint to a relatively small number of scattered forts and trading posts so that natural habitat could be preserved and the Indians could continue to live on the land and gather furs for French markets. British colonization, in contrast, was much more aggressive and posed more dangers to the Indians. There were more than a million British on the eastern seaboard and they had already shown their eagerness to buy land and evict Indians, with or without their consent, to make way for settlements.54

DURING THIS PERIOD OF COMPETITION WITH THE BRITISH, the French implemented a two-pronged policy: expanding westward to find new fur-trading opportunities, and consolidating their hold on the lands they already claimed, which meant extending their system of forts and keeping the British from advancing beyond the Appalachians. Westward expansion netted some promising results, including those from the travels of Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de la Vérendrye, and his sons, which led to increased trade with the Cree and the Assiniboin, the building of new posts as far west as Lake Manitoba, and an expedition in search of the Pacific coast that took one of the sons all the way to the foot of the Rocky Mountains near the Big Horn range.55 Consolidation, too, proceeded apace, as a growing array of French fur-trading posts stretched from the Gulf of Mexico up through the Mississippi Valley to Canada, the most important of which was Fort Detroit, established by Antoine de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, in 1701.56 On the other hand French policy of stemming the English advance over the Appalachians failed miserably. With each passing year British traders were a more common sight on the western side of the mountains.

While the French were bemoaning the British incursions, the British were growing increasingly concerned about the French. New France’s designs on the territory west of the Appalachians angered British colonists for three reasons. First, many of the royal patents establishing the British colonies gave them rights to land stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific and they argued that that included all the lands occupied by the French.57 Second, the British believed that their special relationship with the Iroquois confederacy—now the six nations with the addition of the Tuscarora—supported their claim to the disputed lands. After all, the Treaty of Utrecht had declared the Iroquois to be British subjects, and in British eyes this meant that any lands conquered by the Iroquois necessarily became part of the British Empire. A lot therefore turned on how one defined “conquered,” and the British chose to do so quite liberally. As the historian Francis Parkman points out, the British “laid claim to every mountain, forest, or prairie where an Iroquois had taken a scalp,” and that included most of the “country between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi.”58 Finally, the British didn’t want the French to monopolize the fur trade. As Cadwallader Colden, surveyor general of New York, wrote in 1724, New France “extends from the mouth of the river Mississippi, to the mouth of the river St. Lawrence, by which the French plainly show their intention of enclosing the British settlements, and cutting us off from all commerce with the numerous nations of Indians, that are everywhere settled over the vast continent of North America.”59

For all these reasons the British saw the French as interlopers on British land and not the other way around. And the British colonists feared that should the French succeed in usurping these lands and keeping the British hemmed in on the eastern side of the Appalachians, the colonies would “wither and die for lack of expansion.”60 Thus, for an increasing number of British colonists the solution to the French problem was not continued hostile coexistence, but rather conquest. If the French could be chased from the continent, then the disputed lands and the fur trade would fall into British hands.61

BY THE EARLY 1740S IT APPEARED THAT THE LONG PEACE between the French and British in North America was on the verge of shattering. The War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) had engulfed much of Europe, and Britain and France would soon be dragged into the fray. The war finally spilled over into America in 1744, where it was called King George’s War (1744–48). Bloody, dramatic, and long, King George’s War nevertheless failed to reduce any of the tensions between the British and the French because the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the war, restored the status quo ante bellum, returning all captured territories to their original owners. Although the war didn’t resolve the disputes between the French and the British over contested lands, it had a dramatic impact on the balance of power in the fur trade, which in turn set in motion a series of events that transformed the Ohio Valley into a battlefield and ignited another intercolonial war that resulted in the downfall of New France.62

During the war, British victories on land and supremacy at sea virtually halted the supply of goods coming into New France, and without those goods the French found it nearly impossible to compete with the British for the fur trade, especially in the Ohio Valley.63 British traders, who still had plenty of high quality goods, seized this opening, finding the Indians only too willing to switch allegiances, placing their current commercial interests far above their historical ties to the French. In 1747 Pennsylvania fur trader George Croghan wrote a letter to the provincial secretary of the colony that clearly showed the new dynamic in the valley. “I am just returned from the woods, and have brought a letter, a French scalp, and some wampum, for the governor, from a part of the Six Nation Indians that have their dwelling on the border of Lake Erie. Those Indians were always in the French interest till now, but this spring almost all the Indians in the woods have declared against the French: and I think this will be a fair opportunity, if pursued by some small presents, to have all the French cut off in them parts.”64 As if to prove Croghan’s point, a Miami Indian chief called La Demoiselle by the French, frustrated by New France’s lack of goods and high prices, turned his back on the French that same year and led his tribe south to the confluence of Lorraine Creek and the Great Miami River, where he established the village of Pickawillany and welcomed the British with open arms. Pennsylvanians, who dubbed La Demoiselle “Old Briton,” flocked to the new village, built a rudimentary trading post, and established a thriving fur trade.65

WITH THE CONCLUSION OF THE WAR THE FRENCH WERE determined to regain control of the Ohio Valley. Not only was the loss of the fur trade a serious blow, but the valley itself was also a key to the future integrity of New France. As Parkman put it:

French America had two heads—one among the snows of Canada, and one among the canebrakes of Louisiana; one communicating with the world through the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the other through the Gulf of Mexico. These vital points were feebly connected by a chain of military posts[.]…Midway between Canada and Louisiana lay the valley of the Ohio. If the English should seize it, they would sever the chain of posts, and cut French America asunder. If the French held it, and entrenched themselves well along its eastern limits, they would shut their rivals between the Alleghenies and the sea, control all the tribes of the West, and turn them, in case of war, against the English borders.66

New France’s first gambit was to reassert its sovereignty over the Ohio Valley, persuade the Indians to return to the French fold, and warn the British traders to leave the area at once. With these goals in mind Capt. Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville led two hundred French soldiers and thirty Indians into the heart of the valley. At the junctions of key rivers Céloron nailed plates of tin embossed with the arms of France to the largest trees, and planted lead markers in the ground beneath them proclaiming in no uncertain terms that this was French land and that the French had returned to claim what was rightfully theirs.67 Céloron met with any Indians he could find, including Old Briton, to persuade them to renounce their associations with the British. At a Seneca village he relayed a message from the marquis de la Galissonière, governor of New France. “My children, since I was at war with the English, I have learned that they have seduced you; and not content with corrupting your hearts, have taken advantage of my absence to invade lands which are not theirs, but mine…. I will not endure the English on my land. Listen to me, children…follow my advice, and the sky will always be calm and clear over your villages.” The Indians were quick to tell Céloron that they would renew their allegiance to the French, but Father Bonnecamp, the expedition’s chaplain, knew better—“We should all have been satisfied if we had thought them sincere; but nobody doubted that fear had extorted their answer.”68

And although Céloron was able to run off a few of the British traders, some refused to leave. Getting rid of the British, he now realized, was not going to be easy.

At a gathering of representatives from the Iroquois Confederacy, the Miami, Delaware, Shawnee, and Huron convened in 1751 at the Indian village of Logstown, in the vicinity of modern-day Pittsburgh, the French tried once again to reason with the Indians. A French officer, who was half Seneca, named Philippe Thomas Joncaire urged the Indians to banish the British from the valley and instead trade with the French.69 “The English are much less anxious to take away your peltries,” argued Joncaire, “than to become masters of your lands; they labor only to debauch you; you have the weakness to listen to them, and your blindness is so great, that you do not perceive that the very hand that caresses you, will scourge you like negroes and slaves, as soon as it will have got possession of those lands.”70 No sooner had Joncaire sat down than an Iroquois chief stood up to speak: “Fathers, I mean you that call yourselves our fathers, hear what I am going to say to you. You desire we may turn our brothers the English away, and not suffer them to come trade with us again; I now tell you from our hearts we will not, for we ourselves brought them here to trade with us, and they shall live amongst us as long as there is one of us alive.”71 Such repudiation was exactly what the Pennsylvania traders in the audience, including Croghan, wanted to hear. And to strengthen their relationship with the Indians, the Pennsylvanians distributed seven hundred pounds worth of gifts to the Indians.

BUT THE TIDE IN THE VALLEY WAS ABOUT TO TURN IN FAVOR of the French. The leaders of New France had long been calling for the destruction of Pickawillany, viewing the British traders there and Old Briton as the “instigators of revolt [in the Ohio] and the source of all our woes.”72 In June 1752 those leaders got what they were asking for when the French trader Charles-Michel de Langlade and a force of 250 Chippewa and Ottawa sacked Pickawillany, and to celebrate their victory feasted on the roasted flesh of Old Briton.73 This bold move devastated the British trade in the region and caused many Indians to realign themselves with the French.

The following year Michel-Ange Duquesne de Menneville, marquis Duquesne, the governor general of New France, implemented a plan intended to drive out any remaining British traders and permanently discourage the British from settling in the Ohio. Duquesne’s forces built forts at Presqu’isle (now Erie, Pennsylvania), and on the Rivière aux Boeuf (now French Creek), a tributary of the Allegheny River. They also took over and fortified a small British trading post at Venango (now Franklin, Pennsylvania). Duquesne had planned to construct yet another fort at the Forks of the Ohio, where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join to form the Ohio, which the French called la Belle Rivière (the beautiful river). Of all the forts envisioned by Duquesne, this was the most crucial because the Forks, at the site of modern Pittsburgh, were the strategic key to controlling the Ohio Valley and the gateway to the upper Mississippi. But the realization of Duquesne’s vision would have to wait. His men, ill, tired, and low on supplies, were in no condition to press on.74

Duquesne’s aggressive moves in the Ohio provoked a sharp British response. The French had to be stopped, or the entire Ohio would fall under their control. A contemporary letter to the editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette, signed “A Friend to Publick Liberty,” made the case for swift action: “There are they who are now, contrary to all justice, invading the English settlements all around…. What must inevitably be the consequences if they are permitted to settle and erect forts? I tremble to think;—the loss of liberty, devastation, and ruin;—my heart can speak no more…. A branch of trade of no less value than forty thousand pounds per annum (I mean the fur trade) totally cut off…if you have any love for your country, rouse at length in its defense, and show by your present conduct that you are not unworthy of the liberty you enjoy.”75 The British home government, alive to the threat, ordered the colonies to resist any French incursions, by force if need be.76

Virginia’s governor, Robert Dinwiddie, took up the call. Virginia had long claimed rights to the Ohio, which the French were now threatening—incentive enough for Dinwiddie to fight back. But Dinwiddie also had another, more personal reason for wanting the French out of the valley. In 1749 King George II granted a group of prominent Virginians five hundred thousand acres of land in and around the Forks of the Ohio, with the understanding that they would settle and defend the area with a fort. The investors in this Ohio Company were also very eager to exploit the area’s fur trade, seeing it as an excellent way to support subsequent settlement. Dinwiddie was one of those investors.77 The London Board of Trade and Plantations heartily approved of Dinwiddie’s aggressive stance, and if he needed further encouragement, he received it in a letter from an Ohio Company agent and fur trader named William Trent. “The eyes of all the Indians are fixed upon you,” wrote Trent on August 11, 1753. “You have it now in your power with a small expense to save this whole country for his Majesty, but if the opportunity is missed it will never be in the power of the English to recover it but by a great expense and the united force of all the colonies…. [The French] tell the Indians in all their speeches that they will drive the English over the Allegheny Mountains.”78

Trent could have added that the Indians were not only listening to but believing the French. The Indians respected strength, and they could see that it was the French who were gaining the upper hand in the region. One contemporary Indian chief spoke for many of his peers when he observed that the British were being humiliated by their European foes. “Look at the French, they are men, they are fortifying everywhere. But we are ashamed to say it, you are all like women, bare and open without any fortifications.”79 If the situation were allowed to stand, it would undoubtedly mean the end for British designs on the Ohio.

The governor’s first salvo in his effort to turn things around was a letter to the French warning them that they were occupying British land and should leave immediately. To perform the delicate task of delivering the letter Dinwiddie chose his protégé, George Washington, a six-foot-three-inch, twenty-one-year-old major in the Virginia militia, who had plenty of physical strength and ambition, but no real-life military or diplomatic experience.80

Washington departed Williamsburg on November 1, 1753, and arrived with his party at the French fort at Venango in early December, where he learned that the French commander to whom he must give the letter was upriver at Fort Le Boeuf. Rather than continue his mission right away, Washington accepted a dinner invitation from Venango’s hospitable officers, one of whom was Joncaire. As Washington later recalled, the wine flowed freely and “soon banished the restraint which at first appeared in…[the French officers’] conversation, and gave a license to their tongues to reveal their sentiments more freely. They told me that it was their absolute design to take possession of the Ohio, and, by G——, they would do it; for that although they were sensible the English could raise two men for their one, yet they knew their motions were too slow and dilatory to prevent any undertaking of theirs.”81 A few days later Washington arrived at Fort Le Boeuf, delivered his letter, and collected the reply. Dinwiddie could hardly have been surprised that the French commander’s answer was a polite but firm no.

Impatient to solidify Virginia’s and the Ohio Company’s claims to the valley, in February 1754 Dinwiddie sent forty-one men, including many carpenters, to the Forks of Ohio to build a fort. Another, much larger force, led by Washington, was supposed to follow soon after, with orders to protect the fort from the French should they be bold enough to attack. But before Washington arrived, disaster struck. On April 17 hundreds of canoes and scores of bateaux, carrying one thousand French troops, and eighteen cannons, descended on the Forks. The Virginians, who were in the midst of constructing their fort, understandably surrendered without a fight. And as soon as they left, the French began building Fort Duquesne on the spot.

Washington was still en route when he received word of France’s bloodless victory. He immediately began laying the groundwork for future military operations intended to retake the Forks, clearing paths through the woods and building a camp at Great Meadows. Learning from Indian allies that thirty-five French soldiers were nearby, Washington, believing them to be a war party sent to hunt him down, decided to attack. The short preemptive battle on the morning of May 28 left one Virginian and fourteen French dead. As it turned out, the French soldiers were indeed looking for the British, but not to fight them. The French commander, Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville, had been sent from Fort Duquesne to deliver a letter to Washington ordering the British to leave the valley or risk incurring the military wrath of the French—ironically enough, a mirror image of the message Washington had delivered to the French just a year earlier.82

The shots fired on the morning of May 28 sparked the French and Indian War in America (1754–63), which would later morph into the Seven Years’ War in Europe (1756–63). The details of the war—its bloody engagements, twists and turns, and shifting fortunes along the ravaged frontier—are beyond the scope of this book. What is important, however, is the outcome: The British won and the French lost. The long battle between these two countries for dominance in America was over. British territory now included Canada, and to the south all the land east of the Mississippi with the exception of New Orleans.83 Many in France took the loss of their North American empire in stride. In 1759 Madame de Pompadour, King Louis XV’s mistress, dismissed the news of the fall of Quebec succinctly: “It makes little difference; Canada is useful only to provide me with furs.”84 And the day the Treaty of Paris was signed, Voltaire wrote to a friend, “Permit me to compliment you. I am like the public; I like the peace better than Canada and I think that France can be happy without Quebec.”85 But as glad as some French may have been to be rid of their American holdings, the victors were happier still.86 For more than a century Britain had been jealous of New France’s fur trade and had coveted the fur-rich lands it possessed. Now those lands were British, and the big question was what the British would do with them.