—9—

“A Perfect Golden Round of Profits”

Title page of Robert Haswell’s journal, September 1787–June 1789.

AMERICANS IN THE LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY HAD only a murky understanding of the West. Once the maps of the day crossed the Mississippi, details became fewer and blank spots multiplied. Over the next century the United States would spread all the way to the Pacific, slowly filling in the map becoming a continental nation. The fur trade played a significant role in this westward movement. America’s first foray to the West was in pursuit of sea otter pelts, and it went not overland, but by sea. The credit for providing the earliest impetus for this venture belongs to Capt. James Cook, a taciturn Yorkshireman who became one of the world’s most daring explorers.

On the eve of the American Revolution, Cook, whose greatest passion was to go where no Westerner had ever gone before already had two remarkable voyages on his résumé, both circumnavigations of the globe in the Southern Hemisphere.1 As commander of the Endeavour (1768–71) one of his primary tasks was to search for terra australis incognita, thought to be a lush, resource-rich continent located near the bottom of the earth. Although Cook didn’t find this bountiful land, he did become the first European to chart the entire coastline of New Zealand, and the first to visit southeastern Australia, naming Botany Bay in the process and making contact with the Aborigines.2

During Cook’s second voyage (1772–75), with the ships Resolution and Adventure under his command, he once again set out and failed to discover the mythical southern continent. Yet, in pursuing this phantom land, Cook sailed the Resolution to within seventy-five miles of Antarctica, and became the first European to cross the Antarctic Circle. Having braved the frigid air and ice-choked waters below the seventy-first parallel, Cook boldly predicted—incorrectly, as it turned out—that because “the risk one runs in exploring a coast in these unknown and icy seas, is so very great,…no man will ever venture farther than I have done; and that the lands which may lie to the south will never be explored.” If terra australis incognita was indeed ever found, Cook averred that it would be “a country doomed by nature never once to feel the warmth of the sun’s rays, but to lie buried in everlasting snow and ice.”3

It was on his third voyage, however, that Cook made his critical contribution to the history of the American fur trade. On July 12, 1776, Cook again sailed from Britain, with 191 men onboard the Resolution and the Discovery, in yet another in the long line of attempts to find the Northwest Passage to the Orient, spurred on by Parliament’s promise of twenty thousand pounds for the first British ship that did so.4 Rather than search for the passage from the Atlantic side of North America, as most earlier failed expeditions had done, Cook planned to sail to the northern Pacific, where he hoped to find the fabled waterway and follow its course clear through (or around North America), ending up at Hudson Bay.

In mid-January 1778, about eighteen months into the journey, Cook and his men became the first Europeans to visit the Hawaiian Islands, which he named the Sandwich Islands in honor of the Earl of Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty and one of his staunchest supporters. The Hawaiians were dumbfounded by the ships’ arrival at the island of Kauai. “In the course of my several voyages,” Cook wrote, “I never before met with the natives of any place so much astonished as these people were upon entering a ship. Their eyes were continually flying from object to object; the wildness of their looks and gestures fully expressing their entire ignorance about everything they saw.” The Hawaiians were quite welcoming, treating Cook in particular as if he were at a minimum a great chief, and possibly even a god. Wherever he went they threw themselves prostrate to pay their respects to the strange and wondrous visitor. Then, in early February, having loaded the ships with copious amounts of food and water, the Resolution and the Discovery proceeded on their voyage.5

A little more than a month later Cook sighted the coast of present-day Oregon and continued sailing north, anchoring in Nootka Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island at the end of March. Almost immediately, observed Cook, “a great many canoes, filled with the natives” surrounded the ships, “and a trade commenced betwixt us and them,” in which the furs of bears, raccoons, sea otters, and other animals were exchanged for various articles, including knives, buttons, and nails. Cook’s men eagerly snapped up the furs to make new clothes to replace their own, in tatters after nearly two years at sea. In the coming months such transactions were repeated multiple times, accumulating fifteen hundred pelts.6

Cook spent much of the rest of 1778 vainly searching for the Northwest Passage, and then headed back to the Hawaiian Islands to give his men time to relax, and to stock up on supplies before resuming his explorations. Coming ashore on January 17, 1779, in Kealakekua Bay on the island of Hawaii, Cook and his men were greeted with a joyous celebration. For the next two and a half weeks the British were treated with even more adoration and deference than they had been accorded on their initial visit. When the Resolution and the Discovery sailed out of Kealakekua Bay in the early hours of February 4, they were escorted by an armada of canoes, a few of which came alongside one of the ships so that the Hawaiians could deliver some hogs and vegetables, a parting gift of friendship.7

Four days later, during a powerful gale, the Resolution’s foremast, already weakened by rot, became dislodged near its base, forcing Cook to head back to Kealakekua for repairs. This time, however, when the British came ashore, the Hawaiians were decidedly cool, then openly hostile. Although the reasons for this dramatic change in attitude, compared with just a week earlier, are the subject of a strident academic debate, the results are not.8

Stealing by the Hawaiians soon escalated into altercations with the British, followed by stone throwing, which in turn led Cook to try to reestablish some order through a measured show of force. He went ashore with his lieutenant and nine armed marines to take the king hostage until the Hawaiians returned the Discovery’s cutter, which had been taken from its mooring. The king agreed to accompany Cook, but as they approached the water’s edge one of the king’s wives, crying hysterically, begged him not to go; and then two chiefs grabbed the king and “forced him to sit down.” All the while the rapidly growing throng of Hawaiians, perhaps three thousand strong, grew more restive. Each time Cook tried to coax the increasingly fearful king to board the boat that would take them to the ship, the two chiefs restrained him. Realizing that forcing the king to come would likely ignite a battle, Cook decided to leave without him. But at that moment news arrived “which gave a fatal turn to the affair.”

Earlier in the day two canoes had tried to run the blockade Cook had established in the bay to keep anyone from leaving until the cutter was returned. Cook’s men had fired at the fleeing canoes, “killing a chief.” As word of the murder spread through the crowd, the Hawaiian men slipped woven “war-mats” over their chests, and armed themselves with stones and spears. One of the men ran up to Cook, gesticulating wildly, threatening to strike. Cook tried to calm him down, but when that failed he fired one of his gun’s barrels, loaded with “small-shot.” The pellets bounced harmlessly off the man’s “war-mat,” and the act of firing only further provoked the Hawaiians, who menacingly edged closer and again started throwing rocks.

One of the Hawaiians, dagger in hand, lunged forward, but the marine who was the intended target parried with a well-placed blow of “the butt end of his musket.” Cook “fired his second barrel, loaded with ball,” killing one of the Hawaiians. While stones rained down on the British, Cook ordered his men to fire and yelled, “Take to the boats.” The marines’ fire was deadly accurate, but before they could reload the crowd rushed forward “with dreadful shouts and yells.” In the melee that ensued, and the mad scramble for the boats, Cook was left behind. As he stood in the surf, urging one of the boats to come get him, he was clubbed and then stabbed in the back. Cook pitched forward into the water, immediately set upon by others who continued the assault, then dragged his body onto the beach where they took turns repeatedly kicking and stabbing him.9

Cook’s men could scarcely believe the “calamity” that had just occurred. Their commander dead, along with four marines, as well as seventeen Hawaiians (and many more wounded on both sides). The men’s grief soon gave way to thoughts of revenge. In the days following Cook’s death, the marines went ashore to collect the repaired foremast and gather water. Rock throwing and threatening advances by the Hawaiians elicited a vicious response from the British, who shot and bayoneted perhaps a dozen Hawaiians, set one of the villages ablaze, and even decapitated two natives, parading their heads about on pikes. The crew’s tempers grew more inflamed when one of the Hawaiian priests paddled into the bay to deliver a package. Wrapped in a piece of cloth was a ten-pound slab of human flesh. It was from Cook’s body, the priest said, claiming that the rest of his body had been burned and that his bones and head were with one of the chiefs. This caused the British to repeat their earlier demand that all of Cook’s remains be returned immediately.

On the morning of February 20 a solemn procession of Hawaiians walked down to the beach and deposited presents of sugarcane and fruit near a white flag stuck in the sand. One of the chiefs beckoned to the ships moored just offshore that a boat be sent to pick him up. The chief held in his hands a beautifully wrapped bundle, which he gave the British. It contained the rest of Cook’s body, or at least what was left of it, including both of his hands, with the flesh still on; the skull, with the scalp cut off and the facial bones missing; and the thigh and leg bones. The next day Cook’s remains were placed in a coffin and consigned to the deep with military honors. With peace restored, the British stayed for another three weeks, during which they charted the rest of the islands. In mid-March the Resolution and the Discovery departed Hawaii.10

NOW UNDER THE COMMAND OF CHARLES CLERKE (WHO would soon die, to be replaced by John Gore), the men visited the Russian settlements on Kamchatka, then continued their fruitless search for the Northwest Passage, and after abandoning that sailed to Canton (Guangzhou), China, to gather supplies for their journey home.11 It was in that bustling port that they made one of the most valuable discoveries of the entire voyage. In late December 1779, Capt. James King, who had taken over command of the Discovery, visited a Chinese merchant to sell twenty sea otter skins. The merchant tried to take advantage of the supposedly naive Briton by offering three hundred dollars for the lot. Although it seemed a large sum on its face, King knew better. During their stop on the Kamchatka Peninsula the British sailors had sold sea otter skins to Russian traders for twice that amount. Thus the hard bargaining began, with King haggling until he received forty dollars per pelt. King soon learned that these already fantastic prices could go even higher. “During our absence [from the ships],” he would later write, “a brisk trade had been carrying on with the Chinese for the sea-otter skins, which had every day been rising in their value,” despite the fact that many of the pelts were “spoiled or worn out.” One lucky seaman sold his lot of furs for $800, a few especially prime skins fetching $120 apiece.12 Such huge sums precipitated in the men an almost uncontrollable urge to return immediately to the Northwest Coast to gather more furs, and a near-mutiny ensued. But order was restored, and the Resolution and the Discovery headed back to Britain, arriving in October 1780. When years later the news of Cook’s voyage, in particular the fur sale in Canton, reached the East Coast of the United States it sparked one of the biggest rushes of the American fur trade, a period when the sea otter pelt reigned supreme.

THE SEA OTTER (ENHYDRA LUTRIS) IS A REMARKABLE AND exceptionally handsome animal. Related to weasels, mink, skunks, and badgers, it spends virtually its entire life in the ocean, rarely if ever coming ashore.13 The smallest of marine mammals, reaching nearly five feet and weighing as much as one hundred pounds, sea otters were originally found in a great arc along the Pacific coast, from the Kurile Islands above Japan, north to the Kamchatka Peninsula, across the Bering Sea to the Aleutian Island chain, and then south to Baja California.

The sea otter spends much of its time either floating on its back at the surface or diving deep, up to four minutes at a time, to gather a smorgasbord of delectable morsels to eat, including sea urchins, crabs, and abalones, which it retrieves by either holding them tight in its paws or tucking them into pocketlike folds of skin under its arms. One of the few animals to use tools, the sea otter often consumes its meal by placing a rock on its belly, grabbing the object of its gustatory desire in its paws, and pounding it violently against the rock until the prey’s shell is fractured and the succulent meat inside exposed. Abalones, whose bodies are covered by a shell on one side only, do not need to be subjected to this punishing treatment; instead the sea otter digs right in to the mollusks’ exposed underside, tearing off big chunks of sweet meat. As for sea urchins, they are approached gingerly, with the sea otter using its dexterous paws to push aside the needle-sharp spines and its mouth to crush the creature’s exoskeleton, getting to the soft jellylike animal within.

Playful, curious, and extremely social, sea otters will often leap about and follow one another in the water like seals or dolphins. They will congregate in large groups, or rafts, of up to one hundred individuals, at times interlocking their paws to keep together as they float serenely atop the ocean swells. In warmer climates they will sometimes wrap themselves in the ribbonlike fronds of kelp rising from the bottom, creating an anchor that keeps them from drifting too far while they sleep. With keen senses of sight, hearing, and especially smell, sea otters are ever alert to danger and are quick to evade predators, including killer whales and white sharks.

Arguably the sea otter’s most fascinating feature is its fur, which can be brown, reddish brown, or black in the body, and lighter or whitish or silvery about the head. Like the beaver the sea otter has two types of hair: the outer guard hairs and the inner downy underfur. With as many as one million hairs per square inch, sea otter fur is the densest of all mammals’, and the most luxurious to the touch.14 William Sturgis, one of the most famous American sea otter traders, who began voyaging to the Pacific Northwest in the late eighteenth century, opined that it gave him “more pleasure to look at a splendid sea-otter skin, than to examine half the pictures that are stuck up for exhibition, and puffed up by pretended connoisseurs,” and that “excepting a beautiful woman and a lovely infant,” the sea otter’s pelt was the most beautiful natural object in the world.15

Unlike many other mammals, the sea otter does not molt. The pelt remains in prime quality throughout the year, with never a season when it is ratty or thin. The fur plays a particularly critical role in thermoregulation. Because the sea otter has no insulating layer of fat, it relies on air bubbles trapped in the underfur to help keep it warm. For that system to work the outer guard hairs must be kept very clean so that they remain waterproof. That is why sea otters spend so much time grooming themselves, and also why they can die of hypothermia or pneumonia if their fur gets dirty or covered with oil. A thick, clean layer of fur, however, is not enough to keep warm. To maintain a constant body temperature in the cold ocean waters the sea otter eats up to 25 percent of its body weight per day to keep its extremely rapid metabolic rate up to speed.16

The sea otter’s pelt inevitably made it a target of the fur trade. By the time Cook’s men arrived in Canton, such pelts had been selling briskly for at least forty years in China, where they were deemed the royal fur, valued more than any other by the rich and powerful, used to trim robes and capes, and to make hats and winter coats.17 The Japanese were trading sea otter pelts to the Chinese by the early 1700s if not before, but it wasn’t until the early 1740s, and the arrival of the Russians, that the sea otter trade became a major entrepreneurial activity.

RUSSIA’S RELENTLESS DRIVE TO THE EAST HAD BEGUN TWO decades earlier when Peter the Great, Russia’s most visionary and expansionist czar, called on one of his most trusted naval officers, the Dane Vitus Bering, and ordered him to travel to the farthest eastern reaches of Siberia and then across the ocean to America, with the goal of bringing the North American continent into Russia’s embrace. Bering’s first expedition lasted five grueling years and ended in failure. Although Peter the Great had died before Bering returned, his successors decided to continue his policy and send Bering forth once again in 1733. Eight and a half years later, after transporting a small army of men and supplies to the Kamchatka coast, building two crude sailing ships, and sailing them nearly two thousand miles to the east, Bering and his men made landfall in America in the middle of July 1741.

Bering’s lieutenant, Alexei Chirikov, on board the St. Paul, sighted land first in the vicinity of Takinis Bay near what is now Sitka Sound. Three days later he sent ten well-armed men ashore to explore, followed five days later by another group to see what had happened to the first. The mystery was solved a few days later when Tlingit Indians in two canoes paddled within view. Despite the Russians waving white handkerchiefs and motioning for them to come closer, the Tlingit stayed far away from the St. Paul. “The fact that the Americans [Indians] did not dare approach our ship,” Chirikov concluded, “leads us to believe that they have either killed or detained our men.”18

Chirikov was now in dire straits. A quarter of his crew had vanished, and with them the only two boats that the St. Paul had onboard, meaning that even if Chirikov wanted to send a party ashore to get water or explore somewhere else along the coast, he could not. Stranded on their ship, with only forty-five casks of water in the hold, Chirikov and his men knew they didn’t have much time before there was nothing left to drink. With no recourse he sailed his leaking boat back to Kamchatka, losing another twenty-one men to scurvy and other illnesses along the way.19

Bering’s adventure onboard the St. Peter was even more harrowing. He sighted land a day later than Chirikov, a little way southeast of modern Cordova, gazing first upon the jagged towering peaks of Mount St. Elias, which soared nearly twenty thousand feet into the sky. After four days of coasting to the northwest Bering finally let his men step ashore. One of the first off the boat was the eighteenth-century German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, part of the large scientific contingent Bering had brought along at the behest of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences. Steller had hoped to document exhaustively the wildlife of the region, but within less than a day Bering announced that the St. Peter was heading back, sending Steller into a rage. “The only reason for this,” Steller later wrote, “was stupid obstinacy, fear of a handful of natives, and pusillanimous homesickness. For ten years Bering had equipped himself for this great enterprise; the explorations lasted ten hours!”20

The next three months on the St. Peter proved a maritime nightmare worthy of Dante’s imagination. Rotten food, lack of water, and tempestuous seas conspired to kill many of the men and nearly destroy the boat. In late October the St. Peter made it to the tip of the Aleutians, a gracefully curving chain of rugged volcanic islands that stretches roughly twelve hundred miles into the Pacific. It appeared as if the St. Peter might finally make it to Kamchatka. But neither the ship nor its crew had anything left. The sails were in tatters, the sixty-year-old Bering was fighting a losing battle against multiple ailments including scurvy, and his men were barely able to stand, much less run the ship. On November 4, after most of the men had resigned themselves to a horrendous death, they sighted land. Fleeting hopes that it might be Kamchatka vanished soon after the crippled ship wrecked on the shore a day or two later. They had discovered a small group of islands off the Kamchatka coast, which would later be named the Komandorski, or Commander Islands, in honor of their commander. And the extinct volcano they were marooned on would become known as Bering Island.

The emaciated men spent nine months on the island, many of them dying there, including Bering, who spent his final days partially buried in the sand in an effort to stay warm and protect himself from the piercing winds. Those who survived did so because of the sea otters—or sea beavers, as the Russians called them—that swam in the waters around the island and occasionally hauled themselves onto the rocks. Despite their infirmities the men were easily able to kill the otters, which provided the main source of food.21 And the animals’ pelts became a form of currency used as stakes in gambling games. As the gambling debts mounted, the sea otters’ plight worsened. “He who had totally ruined himself,” Steller wrote, “tried to recoup his losses through the poor sea otters, which were slaughtered without necessity and consideration only for their skins, their meat being thrown away. When this did not suffice, some began to steal the skins from the others, whereby hate, quarrels, and strife were disseminated through all quarters.” According to Steller’s calculations the men killed at least nine hundred sea otters, far more than would have been necessary if they had been killed for food alone.22

Using materials salvaged from the St. Peter or found naturally on the island, the survivors built a forty-one-foot boat. Launched in early August 1742, it arrived a few weeks later in Petropavlovsk on Kamchatcka’s southeastern shore. The ship was so weighed down that Bering’s replacement, Sven Waxell, ordered that the sea otter skins be thrown overboard during the voyage to lighten the load. The men complied, save Fleet Master Sofron Khitrov, who hid his hoard of prime pelts beneath his bunk, and upon landing in Petropavlovsk smuggled them to shore. Unashamedly he began to boast how he would make a fortune selling the furs to the Chinese. It didn’t take long for Khitrov’s claims that Bering Island and the Aleutians were teeming with sea otters to reach the ears of the promyshleniki, the professional hunters who inhabited the eastern reaches of the Russian empire. “As the quest for the black sable had enticed the promyshleniki from the Volga over the Urals to Siberia,” observed the writer Corey Ford, “so the sea otter was the Golden Fleece which lured these Russian Argonauts across the North Pacific to the Aleutians and Northwest America.”23 The proverbial race was on.

LITTLE MORE THAN BRIGANDS WITH A WELL-DESERVED reputation for using violence to get what they wanted, the promyshleniki swept eastward, leaving a path of utter destruction in their wake. Rather than hunt for sea otters on their own, the promyshleniki usually forced the natives, or Aleuts, as they dubbed them, to do it for them by taking some of them hostage and threatening their lives unless the remaining members of the tribe returned with pelts. This particularly savage form of extortion worked particularly well for the promyshleniki, who were more than willing, and at times almost eager, to slaughter the Aleuts if they disobeyed. When the Aleuts rose up in defiance, bloodbaths ensued. In one particularly gruesome instance, Fedor Solovief, appropriately named the “Terrible Nightingale,” attacked Aleuts on Unmak and Unalaska islands in retaliation for earlier attacks on the promyshleniki, and before he was through had murdered nearly three thousand.24

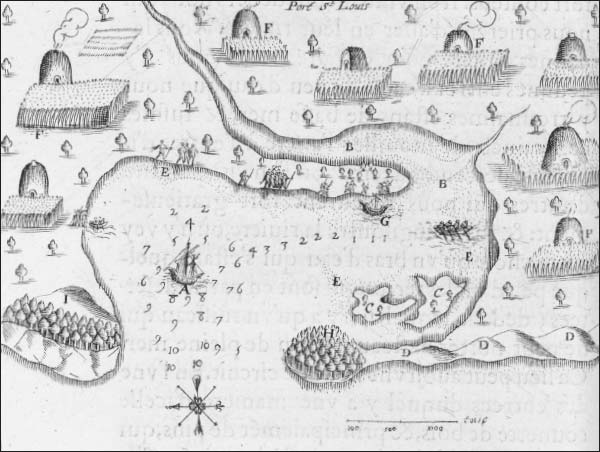

1 | Samuel de Champlain’s map of Plymouth Harbor, 1605.

2 | The first sale of furs at Garroway’s coffeehouse, London, 1671.

3 | Beaver lodge.

4 | Birch tree chewed by a beaver.

5 | Beaver skull.

6 | Beaver dam near the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, Montana.

7 | An assembly line of industrious beavers, employing building techniques never seen in nature, circa 1715.

8 | A British engraving from 1839, showing a scene from the beaver hat-making process.

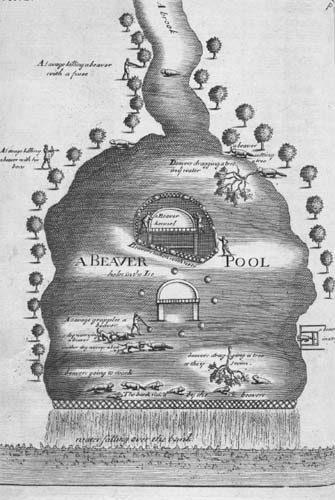

9 | A drawing from 1703, showing beavers going about their business, as well as various Indian hunting methods.

10 | Brass pots used in the fur trade.

11 | Benjamin Franklin wearing his marten fur cap.

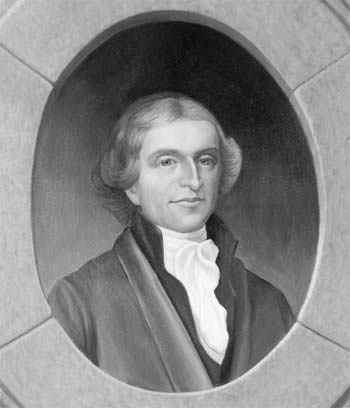

12 | Portrait of John Ledyard by Joseph Swan, 1991.

13 | Maquinna, chief of the Yuquot in Nootka Sound, by Suria, circa 1791.

14 | A 1799 engraving of a Chinese furrier hawking his wares in Canton, China.

15 | Northern fur seal.

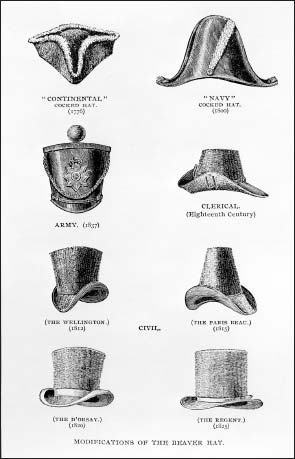

16

17 | One type of beaver trap.

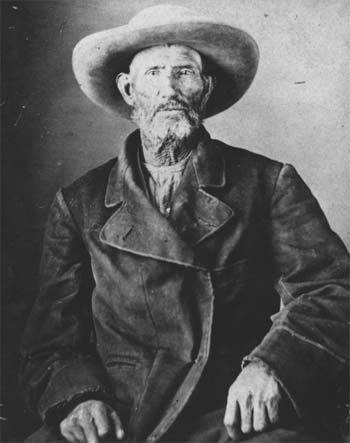

18 | Jim Bridger, between 1860 and 1880.

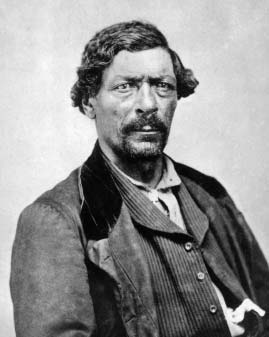

19 | Mountain man James P. Beckwourth.

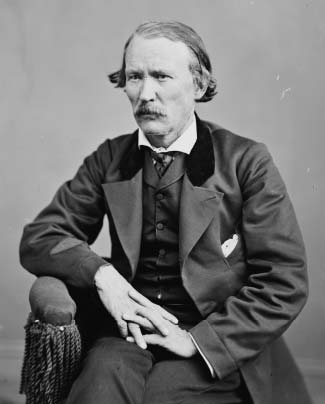

20 | Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson.

21 | This is the Museum of the Fur Trade’s reconstruction of the James Bordeaux trading post in Chadron, Nebraska. The original post was established in the fall of 1837 by Bordeaux to trade with the Indians and provide the American Fur Company with prime buffalo robes.

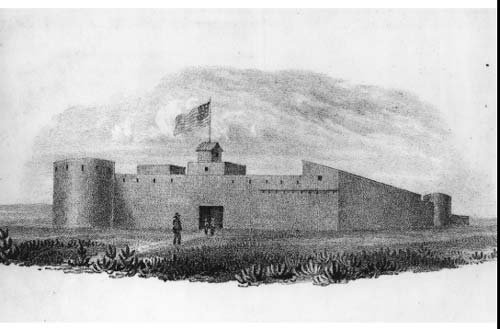

22 | Bent’s Fort, on the Arkansas River, Colorado, 1845. The Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site is a reconstruction of the original fort near La Junta, Colorado, and is operated by the National Park Service.

23 | Fur traders in a mackinaw loaded with furs on the Missouri River, being attacked by Indians.

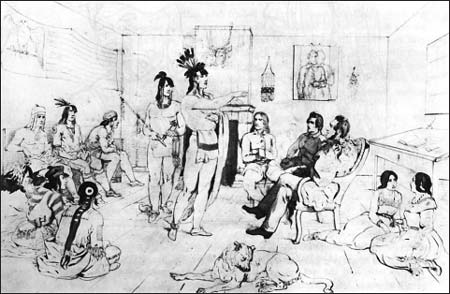

24 | Cree chief All Tattooed meets with the traders in the Indians’ council room at Fort Union, on the upper Missouri. Drawing by Rudolph Kurz, 1851.

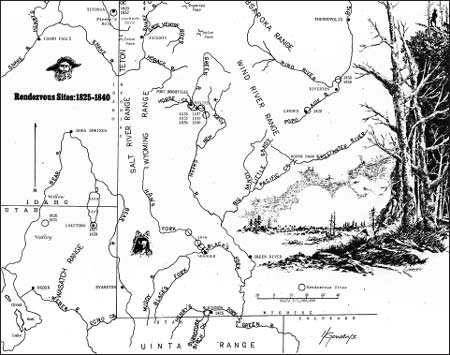

25 | The sites of the Rocky Mountain rendezvous.

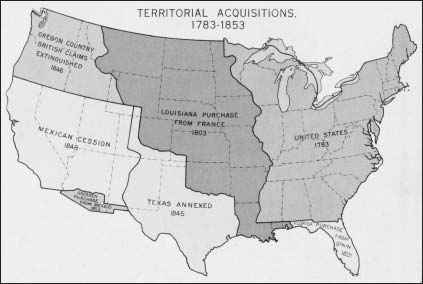

26 | Map showing the growth of the United States, from the Atlas of Historical Geography of the United States, by Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright, 1932.

27 | The oldest known European image of the American buffalo, from Francisco López de Gómara, La Historia General de las Indias, 1554.

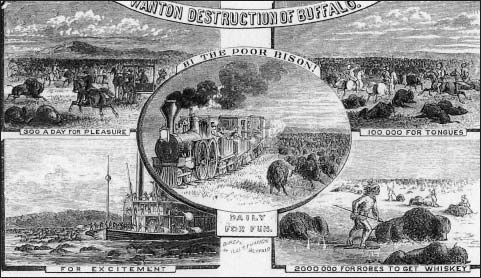

28 | Image from W. E. Webb, Buffalo Land, 1872, showing the various ways in which the buffalo were decimated.

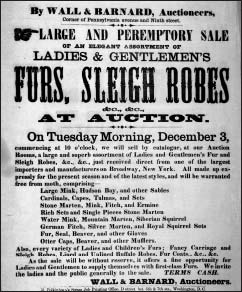

29 | Fur auction advertisement, late 1800s.

30 | Pile of buffalo hides in Dodge City, Kansas; the photograph was taken on April 4, 1874.

31 | Fur trader with his wares.

32 | Woman in the height of fashion, circa 1906.

33 | Sealer with skinned seal carcasses, Pribilof Islands, Alaska, 1892.

The Aleuts used a variety of hunting methods to obtain sea otters for their tormentors. If the tide was out and the otters were up on the rocks, they were clubbed to death. When the otters were in the water, which was nearly all the time, the Aleuts pursued them in one- to three-person skin-covered kayaks called baidarkas, which were twelve to twenty one feet long and fewer than two feet wide. In the hands of skilled paddlers this fast and agile watercraft was perfectly suited for the hunt. Sleeping sea otters were approached cautiously and quietly, then dispatched with a bone- or shell-tipped spear. If an otter was awake, the hunters formed a broad circle around the last place the otter had been seen, and waited for it to resurface. They tried to spear it when it did, repeating this procedure until the increasingly winded sea otter was killed. The Aleuts also employed nets, and on occasion set out otter-shaped wooden decoys that were painted black to lure the sea otters into range. And toward the end of the eighteenth century the Russians taught the Aleuts to hunt with guns.25

By the time of Cook’s ill-fated expedition the sea otter trade had already become a major industry for czarist Russia, where the otter’s pelts were referred to as “soft gold.” Thousands of Aleuts, driven mercilessly by the promyshleniki, killed many hundreds of thousands of sea otters, generating millions of rubles in profits.26 And at the same time some Russians were already looking to the Alaskan mainland and areas farther to the south to expand their trade.

AT THE CLOSE OF THE REVOLUTION, AMERICANS KNEW nothing about the vast sea otter trade with China, but that was all about to change courtesy of John Ledyard, one of the most curious and intriguing characters in early American exploration history. Born in Groton, Connecticut, in 1751, Ledyard had a wandering soul, generating a résumé replete with odd twists and turns. Lasting only a little more than a year at Dartmouth College, he was officially kicked out for failure to pay his bills, but the leaders of the school were not enamored of this “saucy” fellow and his unorthodox ways, and for his part Ledyard disliked the rigid discipline, so the school and the man parted. Rather than travel back to Hartford by road to tell his family the bad news, Ledyard cut down a large pine tree, hollowed it out into a canoe, and paddled it 140 miles down the Connecticut River, becoming the first white man to navigate that span of the waterway. Ledyard floundered about, first failing as a divinity student, then working as a seaman on an American ship transporting mules to the coast of Africa. In 1775 he sailed to London, where he either volunteered for or was impressed into the British army. A short while later he switched to the navy and then, in July 1776, the day after the Declaration of Independence was signed, Ledyard joined Captain Cook’s expedition as a corporal on the Resolution.27

When the expedition returned to London in late 1780, Ledyard was in a quandary. He yearned, like the homesick man he was, to get back to America, but couldn’t very well desert the British navy and sail across the ocean without courting certain capture and a quick hanging. He had to wait for the right opportunity to come to him, and it did in the fall of 1781 when he was sent to Long Island onboard a British frigate to fight the Americans. While on shore leave in November the following year, Ledyard bolted for Connecticut, and after convincing the local authorities that, despite his tenure with the British navy, he was a true American, he settled in and wrote his one and only book—A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, and in Quest of a North-West Passage, between Asia and America, Performed in the Years 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1779—published in 1783.28

Ledyard devoted relatively little space in his book to the sea otter trade, noting that “the skins which did not cost the purchaser six pence sterling sold in China for 100 dollars. Neither did we purchase a quarter part of the beaver and other fur skins we might have done, and most certainly should have done had we known of meeting the opportunity of disposing of them to such an astonishing profit.”29 Although the sea otter trade didn’t figure prominently in his prose, it quickly became his obsession. His dream was to return to the Pacific Northwest and establish a fur-trading operation selling sea otter pelts to the Chinese. During the expedition Ledyard had met with the Russians on Unalaska Island and learned of their success. If they could carry on a lucrative fur trade, so could he. All he needed was to find backers to supply the ships, men, and materials, and among the first persons he approached was one of the richest men in the country, Philadelphia tycoon and signer of the Declaration of Independence, Robert Morris, who granted Ledyard an audience in June 1783. The two men got along well, and Morris threw himself into the venture, leading Ledyard to write to one of his cousins, “but it is a fact that the Hon’l Robert Morris is disposed to give me a ship to go into the N. Pacific Ocean.”30

Morris’s enthusiasm for Ledyard’s plan made sound business sense. Before the Revolution, Americans received most of their goods from the mother country, paying for them with a range of raw materials. After the war the pipeline to and from Britain was virtually cut off, forcing American merchants to look for new ways to invest their capital and obtain the things their countrymen wanted to buy. Among the items most cherished by Americans were the teas, silks, and porcelains of China that had formerly been provided by the British East India Company, which held the monopoly on the China trade. Now that the Americans were no longer part of the British Empire, they could ignore the company’s monopoly and go straight to the source to obtain Chinese goods. The pressing issue facing American merchants, therefore, was precisely what they should trade with China. The Americans knew the Chinese would pay dearly for ginseng, a wild and purportedly medicinal root that grew in the United States. Ginseng alone, however, was a slender thread from which to hang the weight of the entire China trade. American merchants wanted other goods to offer, and sea otter pelts looked to be the perfect addition to their marketing repertoire because they were not only plentiful in the Pacific Northwest but also in great demand in China.31

Frustration and then despair slowly replaced Ledyard’s initial excitement over the project. The partners Morris had enlisted were a motley crew who did little to keep Ledyard informed as planning progressed, and although they managed to build an impressive ship—the Empress of China—their arguments and mistrust of one another fractured relationships and led some of them to withdraw their support. The resulting financial shortfall led to a downsizing of the venture. There would be no stop along the Pacific Northwest to pick up sea otter pelts; instead the ship would sail directly to China with a load of ginseng and other goods to barter. Thus, when the Empress of China left the port of New York on February 22, 1784, Ledyard was not on board.

Deeply discouraged but unwilling to give up, Ledyard traveled first to Spain, then to France, ending up in Lorient in September 1784, where he quickly found enthusiastic backers for his fur-trading venture. His new French partners forged ahead but found it impossible to gain a royal commission for their project or permission to sail to China. Then, in August 1785, the king decided to send the explorer Jean-François de Galaup, the comte de La Pérouse, on a voyage to the Pacific. With France focusing so much of its attention and resources on the La Pérouse expedition, Ledyard’s partners were simply ignored, and once again his dream was deferred.32

Ledyard next went to Paris, where he met American naval hero John Paul Jones and tried to entice him into his fur-trading scheme. Holding out the prospects of profits of as much as 1,000 percent, Ledyard soon hooked Jones, and together they formed a company and began planning their voyage. Their ship, proposed to be a stout 250 tons, crewed by forty-five French sailors, and with Ledyard as the supercargo, would double Cape Horn, visit the Hawaiian Islands, and then head to the Pacific Northwest to commence trading. Once stocked with furs, the ship would sail to Japan to sell the peltry for gold or other goods, and failing that, continue on to Macao. Then it would be back to France, all in the span of eighteen months. Ledyard evinced no doubts in the basic economics of his business model. “Such precious furs might be bought for a bagatelle,” he claimed, “and sold at a market where the venders might fix their own price.”33

But as might be expected in Ledyard’s star-crossed life, his plans began to unravel. One of the investors in the company told Jones that British ships were on their way to the Pacific Northwest, raising the unwelcome specter of competition. Ledyard learned that the Empress of China had succeeded, becoming the first American-flagged ship to trade with China, and he and Jones worried that other American ships might soon follow. The only ships Ledyard could find cost three times what he had budgeted. Jones wanted Robert Morris’s approval for the voyage, but his assent didn’t come. Jones was also somewhat distracted at the time, trying to secure from the French government the prize money he thought he was due as a result of capturing British warships during the American Revolution. The most damaging blow, however, was dealt by the king of Spain, who claimed ownership of pretty much the entire West Coast of America, and had made it clear that the proposed fur-trading expedition would violate Spanish sovereignty. Given that King Louis XVI of France was at the time an ally of Spain, he wasn’t about to allow a French ship to threaten that relationship. All these factors combined to kill the project. With this final rejection, Ledyard wrote to a cousin, “Upon the whole I may venture to say that my enterprise with Paul Jones is no more—that I shall inter this hobby at Paris.”34

WHILE LEDYARD’S PLANS FOUNDERED, OTHERS FORGED ahead, spurred on by the 1784 publication of the official narrative of Cook’s expedition to the Pacific. Whereas Ledyard’s 1783 account barely touched upon the sea otter trade and its potential profitability, the official narrative gave this topic more extensive attention. Not only did it recount the dynamics of trading activity during the voyage, and the great value of the otter pelts, but it also presented a call to action. Cook observed, “The fur of these animals…is certainly softer and finer than that of any others we know of; and therefore the discovery of this part of the continent of North America, where so valuable an article of commerce may be met with, cannot be a matter of indifference.” Captain King added, “The advantages that might be derived from a voyage to that part of the American coast, undertaken with commercial views, appear to me of a degree of importance sufficient to call for the attention of the public.”35

It was King’s intention, of course, to capture the attention of the British. He was not disappointed. As early as 1785 the East India Company and the South Sea Company, which held monopolies on British trade in the Pacific and Canton, licensed a few British ships to enter the Northwest trade. Most British merchants, however, preferring to avoid the rigid constraints imposed by government monopolies, sent their ships out of non-British ports under foreign flags, and in that manner more than a half dozen ships were launched by early 1788.36 But the British were not the only ones who read King’s words: So too did the Americans.

THOMAS BULFINCH, AN EMINENT BOSTON PHYSICIAN, hosted a gathering at his mansion on Bowdoin Square in early 1787. Around the roaring fire, the men’s conversation soon turned to business, more specifically the prospects for Massachusetts’ maritime trade. Relying on Cook’s narrative, and to a lesser extent Ledyard’s account, Joseph Barrell, a Boston merchant, proposed that they join forces, outfit a couple of ships, and enter the sea otter trade. The logic was particularly compelling because Massachusetts’ traders were facing a problem with ginseng. Since the end of the Revolution a growing number of American ships had sailed for China with large amounts of the root to sell. These ships had done well for their owners but in the process had dumped so much ginseng on the Chinese market that the supply outstripped demand. Sending more ginseng was, therefore, a losing proposition. As a result Barrell had little difficulty persuading the small group sitting by Dr. Bulfinch’s hearth that sea otter pelts were their best bet if they wanted to continue the China trade. “There is a rich harvest to be reaped,” Barrell remarked, “by those who shall first go in.”37

Duly excited by the prospects for success, the men raised fifty thousand dollars to purchase two ships, the eighty-four-foot and 212-ton Columbia Rediviva, and its tender, a forty-foot 90-ton sloop, Lady Washington, which were commonly referred to by the sailors themselves as the Columbia and the Washington. John Kendrick was picked to command the expedition and served as captain of the Columbia, while Robert Gray was put in charge of the Washington. Barrell ordered three hundred medals struck, in pewter, copper, and silver, with the images of the two ships on one side and the names of the investors on the other. These, the first die-struck medals to be minted in the United States, were, according to the voyage’s bill of lading, “to be distributed amongst the Natives on the North West Coast of America, and to commemorate the first American Adventure on the Pacific Ocean.”38

The two ships left Boston’s inner harbor on September 30, 1787, with many merchants and friends and family still onboard. That evening, while they were anchored in the outer harbor at Nantasket Roads, a high-spirited farewell party was held on the Columbia. Songs echoed from the main deck, drinks flowed, and before the sailors turned in, their visitors wished them a safe and prosperous voyage.39 The next morning the ships weighed anchor and began their journey.

The Columbia and the Washington kept company all the way to the tip of South America, reaching Cape Horn early the next year. Here was a mighty and fearsome obstacle: Many sailors from other countries had met their end in the tempestuous waters off the Cape, and now it was the Americans’ turn to run the gauntlet, during late winter, no less. For more than a month the men and their ships battled frigid gales that generated seas of a “mountainous height,” which pounded the ships, ripped sails, and at times threatened the bone-weary crews and their vessels with “instant destruction.”40 But they survived, and in mid-April 1788 the Columbia and the Washington became the first American ships to round the Cape. During the passage, however, the two ships had lost sight of each other, forcing them to continue separately on their voyages to the Northwest.

The Washington made better speed, and on August 14 it anchored in Tillamook Bay on the Oregon coast. Salish Indians in dugout canoes visited the ship and commenced trading sea otter skins for knives and axes. A few days later Davis Coolidge and Robert Haswell, the first and second mates, respectively, took a small party ashore. While some men stayed with the boat and others gathered food and water, Coolidge and Haswell visited the local village and watched as the Indians showed off their spear- and arrow-handling skills. They then launched into a war dance, whose gyrations and screaming, Haswell said, “chilled the blood” in his veins.41

Marcus Lopez, Captain Gray’s Cape Verdean cabin boy, was nearby hauling supplies to the boat, when an Indian grabbed Lopez’s cutlass, which he had “carelessly” left in the sand. One of the other crewmen saw what had happened and let out a yell, which brought Coolidge and Haswell running to the spot, only to learn that Lopez had taken off after the Indian. Coolidge, Haswell, and the other man onshore rushed into the woods, and when they rounded a dense clump of trees came upon a harrowing sight. Lopez was in the middle of a throng of Indians, holding the thief by the collar and screaming for help. When the Indians saw the men, they instantly rushed Lopez and “drenched their knives and spears with savage fury in the body of the unfortunate youth,” who staggered forward before being felled by a “flight of arrows” in the back.

The three men ran as fast as they could to the boat while arrows and spears assaulted them from every side. They fired on the Indians, hitting a few, yet still they came. As Coolidge and Haswell waded into the water to get to the boat, an arrow struck the third man, who fell disabled, bleeding profusely, into the surf. The two officers, who were themselves slightly injured, managed to drag the third man to the boat, where the others pulled them onboard and began rowing for the sloop. But it wasn’t over yet. The Indians jumped into canoes and pursued the men, who continued firing until they reached the Washington, whereupon blasts from their sloop’s small cannons hastened the Indians’ retreat. That night the Indians lit bonfires on the shore, howling wildly as they paraded back and forth in front of the flames. For two days, while Gray waited for favorable conditions to make his departure, the Indians taunted the Americans from the beach and on one occasion approached the sloop in canoes only to be turned back with cannon fire. Then, when the tide was right, the Washington sailed out of what the men had dubbed Murderers’ Harbor, and by the middle of September the sloop entered Nootka Sound, the expedition’s designated rendezvous, to wait for the Columbia.

MISERABLE WEATHER PLAGUED THE COLUMBIA’S JOURNEY after rounding Cape Horn, greatly damaging the ship and forcing Kendrick to take refuge at Juan Fernandez Island off the Chilean coast for repairs. When the Columbia finally limped into Nootka Sound in late September, it had already lost two men to scurvy, and the rest of the crew, suffering from the advanced stages of that disease, were barely able to stand. Kendrick realized that it was too late to start trading, so after his men had regained their strength, he ordered them and the crew of the Washington to build houses on the shore of Vancouver Island and settle in for the winter. Between hunting and fishing, the men spent most of their time fashioning iron bars into chisels to trade once warmer weather returned. Haswell took advantage of frequent visits from the Indians to record extensive observations of their physical characteristics and way of life, in addition to compiling a “vocabulary of Nootka Sound,” which ran to more than three hundred words. It included many fascinating and melodious entries such as upsee oop for “hair,” mooxey for “rocks,” yoona for “how many,” and shucksheetle for “to strike.”42 During the spring and summer of 1789 Kendrick and the Columbia stayed in Nootka Sound, while Gray on the Washington sailed up and down the coast from the Queen Charlotte Islands to Cape Flattery, and fifty miles up the Strait of Juan de Fuca, trading with the Nootka, Haida, and Salish, and gaining in one transaction two hundred sea otter pelts for one chisel each. Overall, however, the trading was somewhat sluggish. The Americans found out to their chagrin that Indian tastes in trading goods had changed since Cook and Ledyard had visited, and that many of the trading goods they had stocked in Boston, such as Jew’s harps, snuff bottles, beads, and combs, were not in as much demand as they had expected.43

In July, with supplies running low, Kendrick decided it was time to conclude the trading expedition, divide the pelts, and head to China to sell their cargoes, then return to Boston. Before departing Kendrick switched commands, taking over the Washington while putting Gray in charge of the Columbia. Kendrick, however, never did make it back to Boston. He grew quite fond of his new ship and his own self-importance, and effectively commandeered the Washington for his own use, at one point even selling it to himself in a sham transaction. The rogue freelancer traveled between the Pacific Northwest and China, trading for furs and selling them in Macao. On one voyage he even ventured to Japan, and although he was unable to interest the Japanese in his hold full of sea otter skins, he did become the first known American to visit that “Forbidden Country.” During the return leg of his second trip to China, Kendrick stopped in Hawaii, becoming involved in a dispute involving the natives. He threw in his lot with Capt. William Brown of the Jackal, ending up on the winning side. Kendrick and Brown, flush with victory, decided to toast each other with a cannon salute, using blanks. Unfortunately for Kendrick one of the Jackal’s guns was still loaded, and when the celebratory explosion went off, the cannonball ripped through the side of the Washington, wounding several crewmen and splattering Kendrick’s head about the cabin. Needless to say the original owners of the Washington, who were not happy with Kendrick’s behavior, never got any money from their erstwhile expedition leader.44

GRAY TOOK A DECIDEDLY DIFFERENT PATH. HE STOPPED IN Hawaii before Kendrick, making the Columbia the first American vessel to visit the islands. He stayed there for three weeks gathering supplies, including 150 hogs, and taking onboard a native prince named Attoo who wanted to visit America. Gray then sold his pelts in Canton for $21,404.71, but after factoring in port charges, bribes, and the cost of ship repairs, the profits amounted to only about half as much, and they went toward the purchase of nearly twenty-two thousand pounds of tea.45 Heading west from Canton, Gray rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed into Boston on August 9, 1790, giving the Columbia the honor of being the first American ship to circumnavigate the globe, logging nearly forty-two thousand miles since leaving Boston three years earlier.

When the Columbia came alongside Castle Island, Gray offered a thirteen-gun salute, which was repeated onshore, and then he fired his cannons once again upon mooring in the harbor, causing the “great concourse of citizens assembled on various wharfs…[to respond] with three huzzahs and a hearty welcome.”46 The crowd’s excitement grew when they learned that a native of “Owyhee” was onboard, and soon they saw Attoo, bedecked in “a helmet of feathers that glittered in the sunlight, and an exquisite cloak of the same yellow and scarlet plumage.”47 Attoo walked behind Gray as the two men paraded to the state house for a meeting with Governor John Han-cock, which was followed by a lavish dinner in honor of Gray, his officers, and the Columbia’s owners, during which Gray regaled those in attendance with stories from his trip. The Massachusetts Spy reported, in orotund phrases that were repeated in many other newspapers, that the country was “indebted” to the Columbia’s backers “for this experiment in a branch of commerce before unessayed by Americans,” and that the country was “also under obligation to the…navigators who have conducted this voyage—whose urbanity and civility have secured the friendship of the aboriginals of the country they visited; and whose honor and intrepidity have commanded the protection and respect of the European Lords of the Soil, to the American flag.”48

Despite the fanfare in Boston, the Columbia’s investors had plenty to be glum about. Not only had more than half of the tea been damaged in transit, greatly reducing the voyage’s relatively meager profits, but also Kendrick and the Washington had not returned, and it was beginning to appear that neither ever would. Two of the original investors, greatly discouraged, lost faith and sold their shares in the venture to Gray and a couple of other men. The remaining investors, however, still saw great promise in the Columbia’s return. It had proved the basic feasibility of the business model Barrell had presented at Bulfinch’s fireside back in 1787, and the men believed that, with a little better planning and execution, future voyages would profit handsomely. So confident were they that the Columbia was overhauled, refitted, and sent on another voyage to the Northwest less than two months after its return, with Gray at the helm. This trip, which lasted from September 1790 to July 1793, was much more profitable than the first. But it wasn’t profits for which the Columbia’s second voyage would be remembered.

IN THE WANING DAYS OF APRIL 1792 THE COLUMBIA WAS A little less than fifty miles south of Cape Flattery, along the coast of present-day Washington, when Gray spotted two sails in the distance. They were his majesty’s ships the Discovery and the Chatham, captained by George Vancouver and William Broughton, respectively. Vancouver had been sent to deal with problems the British were having with the Spaniards, to chart the coastline, and to search for the Northwest Passage. Vancouver sent emissaries to meet Gray and gather intelligence about the region, and Gray told them that he had recently “been off the mouth of a river in the latitude of 46° 10', where the outset or reflux was so great as to prevent his entering for nine days.”49 Could this be the almost mythical “Great River of the West” that supposedly led to the Northwest Passage?50 Vancouver didn’t think so. Just a day before encountering the Columbia, Vancouver had been in that vicinity, and noticed that “the sea had…changed from its natural to river-colored water,” but he attributed that to the effects “of some streams falling into the bay,” and not the presence of a mighty river. Vancouver thus concluded that “this opening [was not] worthy of more attention.”51 Gray, however, was of a different mind. So, after sailing northwest in the company of the British, he turned the Columbia around and headed back down the coast. Perhaps, with a bit more persistence, the Great River could be found.

But first a detour. On May 7, off the port bow Gray saw an inlet and went to explore. After crashing through the breakers rolling over the bar at the inlet’s mouth, the men of the Columbia found themselves in an “excellent harbor,” which they called Bulfinch Harbor (now Grays Harbor). Soon canoes full of Indians surrounded the ship, ready to trade. “They appeared to be a savage set,” remarked John Boit, the Columbia’s fifth mate, and were “well armed, every man having his Quiver and Bow slung over his shoulder…. [They] viewed us and the Ship with the greatest astonishment.” Trading proceeded the next day, but that night, under a full moon, some of the men on the Columbia saw canoes approaching and tried to scare them off with cannon shots over their heads. This only set the Indians to whooping and hollering, and when a large canoe with twenty warriors got to within a “1/2 pistol shot of the quarter,” the men fired the nine pounder and ten muskets right at them, which “dashed…[the canoe] all to pieces, and no doubt killed every soul in her,” causing the rest of the canoes to beat a hasty retreat. “I am sorry we was obliged to kill the poor devils,” Boit wrote in his log, “but it could not with safety be avoided.”52

On May 10 Gray continued sailing south, and early the next morning, according to the Columbia’s official log, he “saw the entrance to our desired port bearing east-south-east, distance six leagues.” This time the Columbia made a safe passage over the bar and found itself in the middle of “a large river of fresh water,” ultimately ascending it to a point some thirty miles from the mouth. It was the river Gray had told Vancouver’s emissaries about, which Gray named Columbia’s River, in honor of his ship, but which would soon be shortened to the Columbia River.

GOING ASHORE, GRAY CLAIMED THE RIVER AND THE SURROUNDING land for the United States. For eight days the men explored the river and the adjoining coast, and carried on a vibrant trade with the Indians, who greatly impressed Boit. “The Men, at Columbia’s River, are strait limbed, fine looking fellows,” Boit observed, “and the Women are very pretty. They are all in a state of Nature, except the females, who wear a leaf Apron—perhaps ’twas a fig leaf. But some of our gentlemen, that examined them pretty close, and near, both within and without reported, that it was not a leaf, but a nice wove mat in resemblance!!” Boit also offered his thoughts on the role the Columbia might play in the development of America’s fur trade. “This River…would be a fine place for to set up a Factory [trading post]. The Indians are very numerous, and appeared very civil…we collected 150 Otter, 300 Beaver, and twice the number of other land furs.”53

By July the Columbia was back in Nootka Sound, where Gray and his men were entertained in opulent fashion by Spanish commandant Don Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, who provided a five-course dinner for fifty-four people, with plates, utensils, and everything else were made of “solid silver.” After dinner Gray told his host about his discovery of the Columbia, and even sketched him a map of the area. This transfer of information set off a cascade of events whose reverberations would be felt well into the next century. Soon after Gray left Nootka, Vancouver and Broughton arrived. Bodega told Vancouver about Gray’s discovery, and gave him a copy of Gray’s map, which caused Vancouver to second-guess his earlier dismissal of the “river-colored water” as not meriting further exploration. Had Gray really discovered the Great River of the West? Vancouver had to see for himself, so off he sailed to the southeast on the Discovery, with Broughton on the Chatham following close behind.54

Upon reaching the mouth of the Columbia, Vancouver decided that there was no safe passage for the Discovery across the bar so he left Broughton to investigate while he sailed the Discovery to California. Using a complex set of calculations and rationalizations, Broughton concluded mistakenly that Gray had actually never entered the river proper and that therefore his claims of discovery were null and void. To Broughton this provided a brilliant opportunity to stake his own claim, and with that in mind, he ventured nearly one hundred miles upstream, giving proper British names to a number of land-marks along the way, including Mt. Hood, Vancouver Point, Puget’s Island, Whidbey’s River, and Cape George. To make it official Broughton “took possession of the river, and the country in its vicinity, in His Britannic Majesty’s name,” and then sailed off to rendezvous with the Discovery father down the coast. When Vancouver was briefed on Broughton’s actions, he fully concurred, adding that Broughton had “every reason to believe that the subjects of no other civilized nation or state had ever entered this river before. In this opinion he was confirmed by Mr. Gray’s sketch, in which it does not appear that Mr. Gray either saw or ever was within five leagues of its entrance.” With that bold assertion the stage was set for decades of debates between the United States and Britain over which country had the rights to the region and where the northwestern border of America should be drawn.55

ON HIS SECOND VOYAGE TO THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST COAST, Gray had company. The Columbia’s triumphant return to Boston in 1790 inaugurated what the author David Lavender called “the famous three-cornered trade of the Yankees: Massachusetts gimcracks to the Northwest; Northwestern furs to Canton; and Chinese goods on around the world to Boston.”56 The Columbia’s investors were not the only ones who saw promise in the ship’s first voyage. Other American merchants were watching as well, and they rushed to get a share of the business. In 1791 the Columbia was one of seven American ships trading in the Pacific Northwest, and for the rest of the decade that number fluctuated between three and six. But during these early years the Americans weren’t alone. British, Portuguese, French, Spanish, and Russian ships were also in the area, in search of furs.57

By the turn of the century, however, the Pacific Northwest fur trade had become, in the words of the historian Mary Malloy, “an American specialty, almost an American monopoly.”58 Its remarkable record seemed to reflect the economic dynamo that the new nation was becoming. In 1801, of the twenty-three ships on the coast, twenty were American, two were British, and one Russian. America sustained this dominant position until the early 1830s, and the vast majority of American ships hailed from Boston. So great was the Boston influence that the Northwest Coast Indians thought for many years that Boston was America, and referred to all citizens of the United States as “Boston Men,” in contrast to those coming from Britain, who were called “Kintshautsh (King George) men.”59

A Virginian by birth, President James Monroe noted that “the habits and ordinary pursuits of the New Englanders qualified them in a peculiar manner for carrying on this trade.”60 New Englanders, and in particular Bostonians, had a well-earned reputation as excellent sailors and navigators, sharp traders, and frugal businessmen. They also were less constrained than some of their competitors, particularly the British, by cumbersome regulations and oversight of their activities. In fact once the “Boston Men” left port they were essentially on their own, and were ordered by the owners to use their judgment and bargaining skills to cut the best deals not only with the Indians but also the merchants in Canton. This freedom to improvise and respond flexibly to whatever situation arose gave them a competitive advantage over their would-be rivals, often producing spectacular results. In some years the Americans transported nearly eighteen thousand sea otter pelts to Canton, and when the sales of those were added to those of the other furs they had on board, profits were astronomical, regularly returning as much as 300 to 500 percent on the original investment in the voyage, and in some instances reaching as high as 2,200 percent.61 The key to generating such handsome returns was embedded in the nature of the trade. As one early-twentieth-century historian saw it, “The Americans had a perfect golden round of profits: first, the profit on the original cargo of trading goods when exchanged for furs; second, the profit when the furs were transmuted into Chinese goods; and, third, the profit on those goods when they reached America.”62 Despite these profits, however, success was by no means always assured, there being many instances in which impetuous and inexperienced men entered the Pacific Northwest trade with high hopes, only to have them dashed in the end.

THE DYNAMICS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST SEA OTTER TRADE mirrored those of the fur trade on the East Coast. The Indians were savvy negotiators who quickly learned the value of their furs and how best to get the best deal, often by withholding furs until demands were met or playing one trader off against another. In many instances Indian women did the trading, because, as some of the men said, “women could talk with the white men better than they could, and were willing to talk more.”63 European and American goods were readily incorporated into Indian society and used to enhance “material prosperity” and one’s standing within the community, although as the geographer James R. Gibson argues, these goods “generally…supplemented rather than supplanted Indian products, and served to further, not initiate changes.”64 Alcohol and epidemics tore tribes apart and sent many to an early grave, as did the increased availability and use of guns. And like the eastern trade, the northwestern trade was a source of deadly conflict between whites and Indians. One of the most remarkable examples of such conflict is provided by the case of John R. Jewitt.65

Jewitt, nineteen, was living in the port town of Hull, England, in the summer of 1802, when the American ship Boston arrived to stock up on goods for a fur-trading expedition to the Pacific Northwest. The Boston’s captain, John Salter, hired Jewitt’s father, a blacksmith, to do some work on the ship, and the two quickly became friends. One day, when young Jewitt visited the Boston, Captain Salter invited him to join the crew as the ship’s armorer. Jewitt quickly assented, but his father had severe reservations about sending his son halfway around the world, and took some convincing before agreeing to let him go. In early September the Boston sailed from Hull with twenty-seven men onboard, including Jewitt, who was extremely excited to start his grand adventure.

Jewitt, who had never before been out of sight of land, soon got over his sea-sickness and focused on working at the ship’s forge, repairing muskets and making daggers, knives, and small hatchets. The Boston arrived at Nootka Sound on March 12, 1803. The next day Maquinna, the chief of a Yuquot village in nearby Friendly Cove, visited the ship and offered a warm welcome. Jewitt, who had never seen an Indian before, said he was “particularly struck” by Maquinna’s appearance, noting that he “was a man of a dignified aspect, about six feet in height and extremely straight and well proportioned…. His complexion was of a dark copper hue, though his face, legs, and arms were…so covered with red paint, that their natural color could scarcely be perceived…. His long black hair, which shone with oil, was fastened in a bunch on the top of his head and strewed or powdered all over with white down…. He was dressed in a large mantle or cloak of the black sea otter skin, which reached to his knees.”

Salter hadn’t expected to obtain furs in this place, but rather merely wanted to replenish the ship’s supplies before proceeding farther up the coast; and indeed no fur trading took place. Nevertheless Salter was gracious to the Indians who visited the following week, and after first checking them for hidden arms as a safety precaution, would allow them freely on the ship. One evening Salter had the Indians to dinner, and at its conclusion presented Maquinna a double-barreled fowling gun. The following day Maquinna returned and told Salter that one of the gun’s locks had broken and that it was peshak, or “bad.” “Salter was very much offended at this observation, and considering it as a mark of contempt for his present, he called…[Maquinna] a liar, adding other opprobrious terms.” Salter grabbed the gun from Maquinna and threw it into the cabin, and then told Jewitt, “John, this fellow has broken this beautiful fowling piece, see if you can mend it.” Maquinna took this verbal abuse without uttering a sound, but as Jewitt recalled, it was clear from his “countenance” that the chief was enraged. During the harangue Maquinna repeatedly placed his hand on his throat, then rubbed it on his chest. As Jewitt would later learn, Maquinna did this “to keep down his heart which was rising into his throat and choking him.”

Maquinna and other chiefs, along with many men, visited the ship a day later, and Salter let them onboard. Maquinna seemed quite happy as he paraded around wearing a wooden mask over his head and using a whistle to play a tune, which his men seemed to follow along with as they “[sang] and capered about the deck.” Salter did not know he was being lured into a trap. Maquinna wanted revenge for being treated so rudely, but attacking the entire ship’s complement made him nervous, so his goal was to divide and conquer, which is exactly what he did. Maquinna asked Salter when he intended to leave, and when Salter said the next day, the chief responded, “‘You love salmon—much in Friendly Cove, why not go then and catch some?’” Salter thought this was a capital idea, and after dining with Maquinna and the other chiefs onboard, he sent one of the ship’s boats and nine crewmen to seine for fish. Now the number of Indians onboard was almost as great as the number of white men. Maquinna was about ready to pounce.

Jewitt was belowdecks when he heard a great commotion up top. He ran up the stairs, but as soon as he thrust his head above the deck, an Indian grabbed him by the hair and yanked him into the air. Jewitt’s hair, however, was short and the Indian lost his grip. Seeing his prize slipping away, the Indian swung his ax, hitting Jewitt in the head and sending him hurtling backward onto the deck below, where he lay unconscious, bleeding from a gash in his skull. Nightmarish whooping and hollering awakened Jewitt a short while later. The only reason he remained alive was that Maquinna wanted him that way. The Indian who attacked Jewitt wanted to finish the job but Maquinna ordered him to stop because the chief thought that Jewitt’s skills as the ship’s armorer could be useful to the tribe. Soon after Jewitt came to, Maquinna summoned him to the main deck, where six naked, blood-drenched warriors surrounded him, with daggers raised ready to strike. Maquinna stood before Jewitt and said, “‘John—I speak—you no say no—You say no—daggers come!’” Maquinna asked Jewitt if he would be willing to become his slave, not only to fight alongside the chief in future battles, but also to repair his muskets and make knives and other arms for him. Jewitt assented and then was taken to the quarterdeck, where he beheld what he called “the most horrid sight…ever my eyes witnessed—the heads of our unfortunate Captain and his crew…all arranged in a line.” Jewitt noticed that one of the crew was missing from this macabre display, John Thompson, the Boston’s sailmaker, whom the Indians found the next day. They wanted to kill him, too, but Jewitt was able to save his life by quick thinking, claiming that the older man was actually his father.

Just four days after the massacre two ships appeared in Friendly Cove, but before they got too close to shore, the Indians fired on them with their newly acquired muskets and blunderbusses, and after firing back a few times, the ships sailed away. Thus began more than two years of captivity, during which Jewitt was treated quite well by his captors, yet he never stopped hoping that another ship would arrive and set him free. To hasten that day Jewitt wrote sixteen letters on paper salvaged from the ship, telling of his plight and pleading to be rescued. He gave these letters to visiting Indians, asking that they deliver them to any white men they saw. But no ships appeared. Word of the massacre had spread, and ships scrupulously avoided the area.

In the summer of 1805 Jewitt’s savior arrived. One of his letters had made it into the hands of Sam Hill, the captain of the brig Lydia, a fur-trading ship out of Boston. On July 19 Hill sailed into Friendly Cove, signaling with three cannon shots that he wanted to trade with the Indians. Maquinna was greatly excited. After two years with no fur trading, the white men had finally returned. But how should he handle this golden opportunity? Wouldn’t the men on the ship be very angry over the fate of the Boston’s crew and the imprisonment of Jewitt and Thompson? Finally Maquinna devised a plan. He would visit the ship, but only if Jewitt would write him an introductory letter, telling the ship’s captain that Maquinna had treated Jewitt and Thompson “kindly,” a move the chief hoped would assure a favorable reception. Jewitt readily agreed, but believing that this would be his “only chance of regaining [his]…freedom,” he wrote a letter that was quite different from the one Maquinna had in mind.

To Captain ______________,

of the Brig ______________

Nootka, July 19, 1805.

SIR,

THE bearer of this letter is the Indian king by the name of Maquinna. He was the instigator of the capture the ship Boston, of Boston in North America, John Salter captain, and of the murder of twenty-five men of her crew, the two only survivors being now on shore—Wherefore I hope you will take care to confine him according to his merits, putting in your dead lights, and keeping so good a watch over him, that he cannot escape from you. By so doing we shall be able to obtain our release in the course of a few hours.

JOHN R. JEWITT,

Armourer of the Boston, for himself and

JOHN THOMPSON,

Sail-maker of said ship.

Maquinna grilled Jewitt on the letter’s contents line by line, as Jewitt, feeling as if this “destiny was suspended on the slightest thread,” struggled to maintain his composure, finally convincing the suspicious chief that the message was as he wished. Telling his followers not to worry because “John no lie,” Maquinna climbed into one of his war canoes, and was paddled out to the Lydia, where Jewitt’s plan worked flawlessly. Upon reading the letter Hill had Maquinna placed in irons, and told him he would remain a prisoner until the two men on shore were released. When the Indians realized what had happened, they worked themselves into a frenzy, running back and forth along the shore like “so many lunatics, scratching their faces, and tearing the hair in handfuls from their heads.” Some rushed Jewitt threatening to cut him into “pieces no bigger than their thumb nails.” Jewitt remained calm, telling them, “kill me…if it is your wish, throwing open the bear skin which I wore, here is my breast, I am only one among so many, and can make no resistance, but unless you wish to see your king hanging by his neck to that pole, pointing to the yard arm of the brig, and the sailors firing at him with bullets, you will not do it.” And they didn’t.

After much debating Jewitt told the Indians that the best plan would be for them to trade him and Thompson for Maquinna’s release, to which they agreed. When the two white men, however, finally got onboard the Lydia, and Hill learned the full extent of their story, he wanted to execute Maquinna, but Jewitt rose to defend the old chief. He argued “that Maquinna’s conduct in taking our ship, arose from an insult that he thought he had received from captain Salter, and from the unjustifiable conduct of some masters of vessels, who had [visited the coast in prior years, and] robbed him, and without provocation, killed a number of his people.” Finally Jewitt said that if Hill killed Maquinna, his warriors would exact revenge on the next American ship to enter this cove, and more men would be killed. Convinced, Hill set Maquinna free, and Jewitt began his long journey home.

THE EVENTS SURROUNDING THE BOSTON AND, IN PARTICULAR, the Indians’ attack on the crew must be viewed more broadly to be fully understood. As the author Hilary Stewart notes, “Certainly [the attack]…was triggered by an insult to the high-ranking Maquinna,…but behind the deed also lay a buildup of injustices and mistreatment of the native people by intolerant and greedy white traders.”66 In pleading with Hill to spare Maquinna’s life, Jewitt alluded to such mistreatment, a point which he made more forcefully on another occasion. “I have no doubt,” wrote Jewitt, “that many of the melancholy disasters [along the Pacific Northwest coast] have principally arisen from the imprudent conduct of some of the captains and crews of the ships employed in this trade, in exasperating [the natives] by insulting,…plundering, and even killing them on slight grounds. This, as nothing is more sacred with a savage than their principle of revenge,…induces them to wreak their vengeance upon the first vessel or boat’s crew that offers, making the innocent too frequently suffer for the wrongs of the guilty.”67

In fact the history of the Pacific Northwest coast fur trade is littered with examples of white men, and certainly not just Americans, behaving atrociously and brutalizing the local Indians. Sturgis, whose brother was killed by Indians on the coast, looked back on his many years in the northwestern trade, and concluded that the Indians were often the “victims of injustice, cruelty, and oppression, and of a policy that seems to recognize power as the sole standard of right.”68 Sturgis once told a genteel audience in Boston: “Should I recount all the lawless & brutal acts of white men upon the coast you would think that those who visited it had lost the usual attributes of humanity, and such indeed seemed to be the fact.” The wise old ship’s captain placed the blame for this mainly on the degraded character of the men on these voyages, who “considered” the Indians “little better than brutes,” and “finding themselves beyond the pale of civilization and accountable to no one, pursued their object without scruple as to means, and indulged in every brutal propensity without the slightest restraint.”69 Gibson posits another potential reason why traders on the coast so frequently acted with such cruelty. “Perhaps because they were ‘transient traders,’” who usually made but one voyage to the coast, “they were wont to treat the Natives more callously and brutally than if, like the land fur traders, they had to live among them permanently.”70 The coastal traders also often had the option of making a quick escape by sea, which no doubt encouraged the tendency to strike, plunder, and flee.

Of course not all northwestern fur traders treated the Indians so horrifically. Many trading sessions were civil, and both sides involved perceived the trades to be fair or at least acceptable. But over time problems multiplied. And for every case like Jewitt’s, in which the Indians were the instigators of violence, there were more in which it was the other way around. Similarly, although there were many instances in which the Indians stole from the traders and tried to cheat them in their dealings, it was certainly more common for the traders to try to cheat the Indians and take their furs by force.71 As Sturgis commented, the Indians were “more ‘sinned against’ than ‘sinning.’”72

AMERICAN PROFITS IN THE FUR TRADE WITH CHINA didn’t rely solely on the sale of sea otter pelts from the Pacific Northwest. There were other sources of income. One of the most unusual arose from a unique partnership between the Americans and the Russians. In early October 1803 Joseph O’Cain, the captain of the O’Cain out of Boston, arrived at Kodiak Island off the Alaskan coast with a proposition for Alexander A. Baranov, the chief manager of the Russian American Company, an entity created by the Russian emperor Paul I to control his country’s economic activities in America, including the fur trade. O’Cain told Baranov that the California coast was teeming with sea otters, and all that was needed to get their valuable pelts was hunters who could kill them. If Baranov would provide him with a brigade of Aleuts and a small fleet of baidarkas, O’Cain promised to get those pelts and share them with the Russians.

Baranov was intrigued. The Russian sea otter trade had been a bit anemic lately, making O’Cain’s proposal especially attractive, and Baranov had no compunction about forcibly sending Aleuts, whom he considered no better than chattel, to these distant lands. Also, the Russians were quite interested in getting a foothold in California, and through this venture Baranov might glean valuable information that could contribute to that end. The deal struck, O’Cain left Kodiak at the end of October with forty Aleuts, twenty baidarkas, and one Russian overseer on board, proceeding to San Quentin Bay in Baja California. Living up to their reputation, the Aleuts had soon killed eleven hundred sea otters. O’Cain bought another seven hundred otter pelts from Spanish priests in the area, and in June 1804 returned to Kodiak to give Baranov his share, then sailed for Canton to dispose of the rest.73