WEEK 29

Review your actions nightly

Have you ever had trouble falling asleep because you’re rehashing something you did earlier that day that you regret? Niamh has. She lost her temper at her husband for not taking care of the dishes yet again. Yes, she’d had a long day, and yes, he does neglect his share of things frequently. But instead of working things out, she turned to insults that clearly hurt him and that she now regrets. Niamh doesn’t normally act out like this, and she can’t help but berate herself about her loss of composure. Fortunately the Stoics have a method that allows you to look at and learn from, rather than dwell on, your past actions.

.

The spirit ought to be brought up for examination daily. It was the custom of Sextius when the day was over, and he had betaken himself to rest, to inquire of his spirit: ‘What bad habit of yours have you cured today? What vice have you checked? In what respect are you better?’ Anger will cease, and become more gentle, if it knows that every day it will have to appear before the judgment seat. What can be more admirable than this fashion of discussing the whole of the day’s events? How sweet is the sleep that follows this self-examination? How calm, how sound, and careless is it when our spirit has either received praise or reprimand, and when our secret inquisitor and censor has made his report about our morals? I make use of this privilege, and daily plead my cause before myself: When the lamp is taken out of my sight, and my wife, who knows my habit, has ceased to talk, I pass the whole day in review before myself, and repeat all that I have said and done. I conceal nothing from myself, and omit nothing, for why should I be afraid of any of my shortcomings, when it is in my power to say, ‘I pardon you this time; see that you never do that anymore?’”

The spirit ought to be brought up for examination daily. It was the custom of Sextius when the day was over, and he had betaken himself to rest, to inquire of his spirit: ‘What bad habit of yours have you cured today? What vice have you checked? In what respect are you better?’ Anger will cease, and become more gentle, if it knows that every day it will have to appear before the judgment seat. What can be more admirable than this fashion of discussing the whole of the day’s events? How sweet is the sleep that follows this self-examination? How calm, how sound, and careless is it when our spirit has either received praise or reprimand, and when our secret inquisitor and censor has made his report about our morals? I make use of this privilege, and daily plead my cause before myself: When the lamp is taken out of my sight, and my wife, who knows my habit, has ceased to talk, I pass the whole day in review before myself, and repeat all that I have said and done. I conceal nothing from myself, and omit nothing, for why should I be afraid of any of my shortcomings, when it is in my power to say, ‘I pardon you this time; see that you never do that anymore?’”

Seneca, On Anger, 3.36

.

The evening meditation is one of the most useful Stoic exercises. It is described in some detail by Epictetus in Discourses III, 10, and of course one can imagine the whole of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations as the output of this practice. It’s rather intimidating to take Marcus as your model here—the goal is not to produce the sort of prose that has rightly impressed posterity for almost two millennia. The objective, rather, is to achieve exactly what Seneca describes: the peace of mind that comes from having honestly examined our deeds of the day. We should reflect on what we did, learn from our mistakes, and orient ourselves toward better conduct in the future. This last point should be emphasized; the goal is not to beat yourself up about your past failings, as Seneca specifically mentions—he “pardons” himself, which is in line with modern psychological research emphasizing the importance of self-compassion.1 But the pardon has a caveat: that he try not to repeat his past moral failings in the future. After all, the past is not in your control (short of inventing a time machine), so being upset by it would go against the dichotomy of control. Rather, the point of reviewing your actions is to learn from your mistakes.

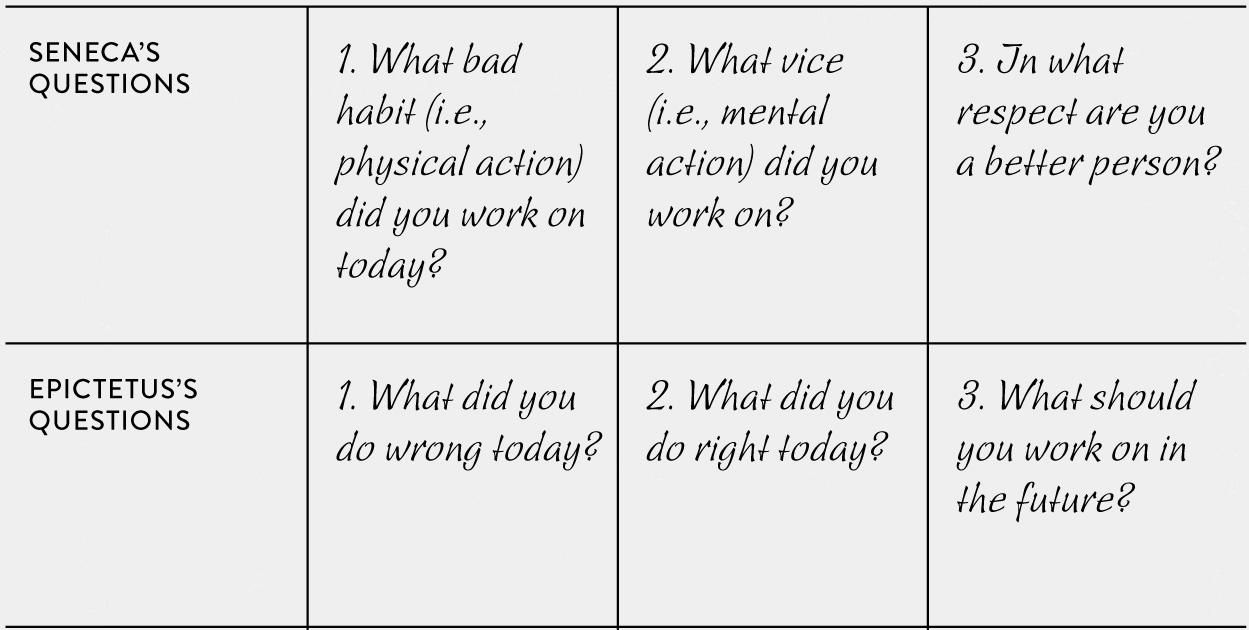

The Epictetian version of the evening meditation suggests that we ask ourselves three specific questions: Where have we gone wrong? What have we done right? What is left, as yet, undone? The goal of the first question is to humbly learn from our mistakes. The purpose of the second is to practice shifting our natural propensity away from erroneous thinking and toward right thinking, by taking time to acknowledge when right thinking has occurred (although note that vanity is not a Stoic virtue). The third question is future directed, aimed at preparing our minds for the tasks ahead and focusing on what is important as well as on the best way to accomplish it.

Psychologist Maud Purcell summarizes the benefits of what today is known as journaling: It clarifies (to yourself) your own thoughts and feelings, it allows you to know yourself better, it reduces stress (especially when writing about negative emotions like anger), it helps you tackle problems more effectively, and it makes it easier to resolve your disagreements with others.2 Or as the Stoics would put it, journaling makes you a better person, capable of learning and better equipped to deal with challenges and, as a consequence, more serene when facing such challenges.

Interestingly, research by psychologists Philip Ullrich and Susan Lutgendorf explored the effects of journaling in response to stressful events when people focus only on their emotional reactions, as contrasted to when they process emotions only by thinking about them.3 Their results were clear:

Writers focusing on cognitions and emotions developed greater awareness of the positive benefits of the stressful event than the other two groups [including a neutral control]. This effect was apparently mediated by greater cognitive processing during writing. Writers focusing on emotions alone reported more severe illness symptoms during the study than those in other conditions. This effect appeared to be mediated by a greater focus on negative emotional expression during writing.4

In other words, Stoic meditation, which today we call cognitive journaling, turns out to have anticipated modern psychology by a couple of millennia.

This week you’ll practice guided journaling by following a set of questions—either Seneca’s, Epictetus’s, or your own. We’ve reproduced both of the ancient versions, and left space for you to devise your own three questions if you’d prefer.

A tip on writing your own questions: Remember that the goal of the exercise is to focus on your virtue. It can be easy to slip into a project management system (“What’s left undone? Well, I need to drop off the dry cleaning!”) or performance review (“I’ve gotten much better at getting my reports in on time”), but that’s not the point. Instead, keep in mind ways to improve your character and the four virtues (wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance), both when doing the exercise during the week and if you write your own questions.

With that out of the way, choose which set of questions you’d like to work with this week, or write your own.

Now that you have your three questions at hand, your goal for this week is to answer them each night.

Seneca claims that this type of reflective journaling leads to sound sleep and peace of mind. That may sound a little strange. How can meditating on our character flaws put our minds at ease? First, remember that this exercise should be accompanied by self-compassion; your past actions are in the past, and therefore out of your control. You are meditating to improve your character. Second, thinking about past mistakes can help you generate action plans for improvement, which will allow you to mold yourself into the person you’d like to be. Finally, both Epictetus’s and Seneca’s prompts explicitly encourage acknowledging what you’ve done well over the course of your day. Take some time to appreciate your decisions—again, not for the sake of vanity, but in order to learn from yourself, and to feel that some good has come from your day in the process.

Did Seneca’s claims about sleeping more soundly after this exercise hold true for you this week? Did you discover any additional benefits? Take some time to reflect on your experience journaling the Stoic way.

If you’d like to continue this practice in the future, bookmark this page.