Chapter 2

Critique and Science in Capital

Preliminary

This exposition proposes to show what problems articulate the reorganization of Marx’s conceptual field, the reorganization which constitutes the transition from the ideological discourse of the Young Marx to Marx’s scientific discourse. Actually, there can be no question of a systematic exposition, which would presuppose that Marxism’s concept of scientificity was fully grasped and could be expounded in a unitary discourse. Hence my method will be to start from different points, different sites, in an attempt to circumscribe the specificity of Marx’s discourse in Capital by a series of approximations.

In general, Marx no longer gives this specificity the name ‘critique’, but rather the name ‘science’. A famous letter to Kugelmann (28 December 1862) ranks Capital among the ‘scientific attempts to revolutionize a science’ (MECW 41, p. 436). This project to revolutionize a constituted scientific domain is something quite different from the project to read into a discourse an implicit sub-discourse, the project which characterized the anthropological critique. However, Marx does also use the term ‘critique’ to designate this new specific project – the subtitle of Capital is ample evidence of this. Thus, in a letter to Lassalle on 22 February 1858, he writes:

The work I am presently concerned with is a Critique of Economic Categories or, if you like, a critical exposé of the system of the bourgeois economy. It is at once an exposé and, by the same token, a critique of the system (MECW 40, p. 270).

In approaching the problems raised by this project to revolutionize a science I shall assume familiarity with a number of points. These are, essentially:

– The location of what I have called economic reality in the ‘economic structure of society’ as defined by Marx in the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), i.e., I shall presuppose familiarity with the concepts of historical materialism;

– The problematic of the method expounded in the general Introduction of 1857.

The questions I shall attempt to pose are therefore as follows:

If Marx revolutionized a science, founded a new scientific domain, what is the configuration of that domain? How are its objects and the relations between those objects defined? If Marx founded this new science by the critique of economic categories, what is the basis for the essential difference between this new science and classical economics? Further, what in its theory will enable us to understand the economic discourses it refutes, that of classical economics and that of vulgar economics? At the same time, I shall tender another question, as I promised: What becomes of the anthropological problematic of the 1844 Manuscripts in Capital?

This last question can be posed by using a particular interpretation of Marx as a reference, the interpretation developed by Della Volpe’s school. According to this interpretation, to criticize economics in Capital Marx used the critical model he had worked out in the manuscript of 1843 entitled Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law (MECW 3, pp. 3–129).

In this text, in order to criticize Hegel’s philosophy of Staatsrecht, Marx used the Feuerbachian critical model, the model of the subject/predicate inversion. This model aimed to show that Hegel everywhere turned the autonomized predicate into the true subject.

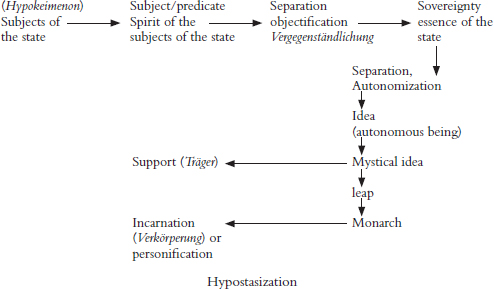

As a concrete example, Marx takes the concept of sovereignty. Sovereignty, he says, is nothing but the spirit of the subjects of the state. It is therefore the predicate of a substantial subject (Marx defines this subject as hypokeimenon, as a substance). In alienation, this predicate, this spirit of the subjects of the state, is separated from its subject. It appears as the essence of the state. This separate existence of the subject and the predicate enables Hegel to make the speculative operation: by a new separation he separates sovereignty from the real state, he makes it into an idea, an autonomous being. This autonomous being has to have a support. This support is provided by the Hegelian Idea, what Marx calls the Mystical Idea. Sovereignty becomes a determination of this Mystical Idea.

Once he has completed this movement of abstraction, Hegel has to make the inverse movement and redescend towards the concrete. The link between the abstract idea and the concrete empirical reality can only be made in a mystical way, by an incarnation. This incarnation allows the abstract determination to exist in the concrete. The Mystical Idea is incarnated in a particular individual, the monarch. The latter then appears for Hegel as the immediate existence of sovereignty.

Let me summarize this movement in the figure below. Marx calls this movement hypostatization. It consists of the separation of a predicate from its subject, its hypostatization into an abstract category which is then incarnated in some empirical existence. Marx also says that we are dealing with an inversion of the empirical into speculation (abstraction and autonomization) and of speculation into the empirical (incarnation). This critical model is thus governed by two oppositional couples: subject/object and empirical/speculation.

According to Della Volpe, this is the model Marx used to criticize classical political economy in A Contribution and in Capital. Classical political economy separates the economic categories from their subject which is a determinate society, and hypostasizes them into general conditions, eternal laws of production. It then moves from speculation to the empirical by making the determinate, historical, economic categories of the capitalist mode of production into a mere incarnation of general categories which are those of all production.

A particularly clear example of the use of this schema can be found in Marx’s critique of John Stuart Mill in the 1857 Introduction. Thus, in Mill, private property appears as the empirical existence of the abstract category of appropriation. There is no production, says Mill, without the appropriation of nature by man. Hence property is a general condition of all production. This abstract category is then incarnated in a very special type of property, capitalist private property.

Using passages such as this, and the pages from the general Introduction on ‘determinate abstraction’, Della Volpe sums up the critical work carried out by Marx; he opposed classical economics by everywhere substituting determinate (historical) abstraction for indeterminate general abstractions or hypostases.

Such an interpretation seems to neglect one essential problem, that of the theoretical conditions necessary for the model of the 1843 text to be able to work. For this, the two oppositions, subject/object and empirical/speculation, must be pertinent oppositions within the theoretical field of Capital.

First of all, we must be dealing with a subject. For the model to be able to work, society has to play the part of a subject which humanity played in the anthropological discourse. Two passages in the general Introduction really do speak of society as a subject. But this definition of society as a subject is condemned by Marx elsewhere and, as we shall see, it is incompatible with the concepts he sets to work in Capital. On the other hand, the application of the empirical/speculation model presupposes a certain kind of relation between economic reality and economic discourse. If this relation no longer exists in Capital, this couple ceases to be operational.

It is on the basis of this problematic that I shall seek to define the specificity of the ‘critique of political economy’ constituted by Capital. This will give us an index which enables us to determine whether we really are dealing with a change of theoretical terrain.

(1) The Problem of the Starting-Point and the Critical Question

a) Value and value-form

We know the importance Marx attributed to the problem of the starting-point of a science in the general Introduction of 1857. The fundamental character of this question is confirmed in Capital. Thus when Marx is criticising Smith in Volume Two, for example, he states that the source of his errors and contradictions has to be looked for in his ‘scientific starting-points’. Hence this is the level at which we ought to be able to find the difference between Marx and classical economics.

What defines the scientificity of classical economics for Marx?

Classical economics seeks to reduce the various fixed and mutually alien forms of wealth to their inner unity by means of analysis and to strip away the form (Gestalt) in which they exist independently alongside one another. It seeks to grasp (begreifen) the inner connection (inhere Zusammenhang) in contrast to the mulitiplicity of outward forms (Erscheinungsformen) (Theories of Surplus-Value, MECW 32, p. 499).

In Capital (Vol. 3, p. 969), Marx uses the word auflösen (dissolve) to designate the work of classical economics. Classical economics dissolves the fixed forms of wealth, an operation which, in the same text, Marx describes as a critical operation. This dissolution is a return to an inner unity, the determination of value by labour time.

Classical political economy is thus constituted as a science by its installation of a difference between the diversity of phenomenal forms and the inner unity of the essence. But it does not reflect the concept of this difference. Look at its application in Ricardo:

Ricardo starts out from the determination of the relative values (or exchangeable values) of commodities by ‘the quantity of labour’ … Their substance is labour. That is why they are ‘values’. Their magnitude varies, according to whether they contain more or less of this substance (Theories of Surplus-Value, MECW 31, p. 389).

Ricardo determines two things: the substance of value which is labour; and the magnitude of value which is measured by labour time. But he neglects a third term: ‘Ricardo does not examine the form – the peculiar characteristic of labour that creates exchange-value or manifests itself in exchange-values – the nature of this labour’ (ibid.).

In the analysis of value which is Ricardo’s scientific starting-point, there is thus an absent term in the first chapter of Capital: ‘The substance of value and the magnitude of value have now been determined. The form of value remains to be analysed’ (Le Capital, t. 1, p. 62; not in the English edition).

This is the work Ricardo never did. He was satisfied with the restored unity. The dissolution (Auflösung) of the fixed forms of wealth he regarded as the solution (Lösung) of the problem of value. Marx’s procedure, on the contrary, as Engels points out in the Preface to Volume Two, is to see in this solution a problem. Marx poses the question we can call the critical question: Why does the content of value take the form of value?

Political economy has indeed analysed value and its magnitude, however incompletely, and has uncovered the content concealed within these forms. But it has never once asked the question why this content has assumed that particular form, that is to say, why labour is expressed (sich darstellt) in value, and why the measurement of labour by its duration is expressed in the magnitude of the value of the product (Capital, Vol. 1, pp. 173–4).

The critical question is the problematization of the content-form relationship. For Ricardo, value is labour. It does not matter in what form this substance appears. For Marx, labour is represented in value, it takes on the form of the value of commodities.

Given the equation: x commodities A = y commodities B, Ricardo resolves it simply by saying that the substance of the value of A is equal to the substance of the value of B. Marx shows that this equation is posed in very special terms. One of the terms only features as use-value, the other only as exchange-value or form of value.

Hence we must pose:

Form of value of A = Natural form of B.

B lends its body, its natural form, for the expression of the value of A. The value must therefore have its form of existence in the natural form of B.

Hence we cannot be satisfied with an affirmation of the identity of the content of A and B. We can see this from the critique Marx made of Bailey in the Theories of Surplus-Value. For Bailey, value is merely a relation between two objects, just as distance is a relation between two objects in space. ‘A thing cannot be valuable in itself without reference to another thing … any more than a thing can be distant in itself without reference to another thing’ (cit. Marx, Theories of Surplus-Value, MECW 32, p. 329).

Look how Marx refutes this argument:

If a thing is distant from another, the distance is in fact a relation between the one thing and the other; but at the same time, the distance is something different from this relation between the two things. It is a dimension of space, it is some length which may as well express the distance of two other things besides those compared. But this is not all. If we speak of the distance as a relation between two things, we suppose something ‘intrinsic’, some ‘property’ of the things themselves, which enables them to be distant from each other. What is the distance between the syllable A and a table? The question would be nonsensical. In speaking of the distance of two things, we speak of their difference in space. Thus we suppose both of them to be contained in the space, to be points of space. Thus we equalize them as being both existences of space, and only after having them equalized sub specie spatii we distinguish them as different points of space. To belong to space is their unity (ibid., p. 330).

This text seems to me to be open to two readings. At one level, Marx is defending Ricardo against Bailey’s criticism by disengaging the existence of a substance of value. The existence of this substance common to the two terms of the relation means that we are not dealing with a relation of the type A = table. This last relation is an absurd, irrational relation. By disengaging the substance of value, Ricardo avoids irrationality at this level. But since he does not disengage the form of value, he condemns himself to fall in his turn into contradiction and irrationality where more complex and developed forms than the commodity form are concerned.

What Ricardo omits is the critical question, the question of the ‘=’ sign. As we have seen, this sign is problematic in that it relates together two terms which are presented in absolutely heterogeneous forms. On the one hand we have a pure thing, on the other a pure incarnation of value:

A close scrutiny of the expression of the value of commodity A contained in the value-relation of A to B has shown us that within that relation the natural form of commodity A figures only as the aspect of use-value, while the natural form of B figures only as the form of value (Capital, Vol. 1, p. 153).

The identity posed by the ‘=’ sign thus conceals a most radical difference. It is an identity of opposites. ‘The relative form of value and the equivalent form are two inseparable moments, which belong to and mutually condition each other; but, at the same time, they are mutually exclusive or opposed extremes’ (Vol. 1, p. 139–40). This identity of opposites is only possible because one form (the natural form of B) itself becomes the form of manifestation of its opposite value.

Thus, we see, and could have read implicitly at a second level in the passages on Bailey, that commodities are only equal in the very special mechanism of representation (Darstellung). They are neither equal as mere things, nor even as items of the same substance; they are equal in determinate formal conditions imposed by the structure in which this relation is achieved.

We can make this reference to space say a little more than Marx says about it explicitly. The forms in which the things are related with one another by the dimension of value are forms determined by the structure of a certain space. The properties they take on in the equation must be determined by the properties of the space in which the representation, the Darstellung, is achieved. The installation of this space which makes an impossible equation possible is expressed by a certain number of formal operations: representation, expression, adoption of a form, appearance in such and such a form, etc.

Let us consider one of these operations: ‘Value takes on the form of a thing.’ This examination will enable us to make the meaning of the content/form relation clear; it is a matter of the relation between the inner determination and the mode of existence, the phenomenal form (Erscheinungsform) of this determination.

In fact, the expression means that value has its mode of existence, its phenomenal form (or form of manifestation), in the natural form of the equivalent commodity. The paradox is that value is unable either to appear or to exist. In so far as it appears in the natural form of a commodity, it disappears in it as value, and takes the form of a thing.

Value thus has its form of manifestation in the exchange relation only in so far as it is not manifested there. We are dealing with a type of causality quite new in relation to the 1844 Manuscripts. In the Manuscripts the equations which expressed the contradictions (e.g., the erection of the world of things into values = the depreciation of the world of men; or value of labour = value of means of subsistence) all referred to the equation: essence of man = essence foreign to man, i.e., they referred as their cause to the split between the human subject and its essence. The solution of the equation lay in one of its parts. The essence of man separated from the human subject provided the cause of the contradiction and the solution to the equation. The cause was referred to the act of subjectivity separating from itself.

Here, in the equation, or, what amounts to the same thing, the contradiction: x commodities A = y commodities B, the cause is not in the equation. The latter presents a relation between things, a connection between effects determined by the absence of the cause. This cause lies in the identity of useful labour, creative of use-values, and labour creative of exchange-values, of concrete labour and abstract labour. It is well-known that, in a letter to Engels dated 8 January 1868, Marx declared that the discovery of the double nature of labour (concrete labour and abstract labour) is ‘the whole secret of the critical conception’ (MECW 42, p. 514). This distinction is indeed what enables us to problematize the unity of the two determinations. Classical economics took the concept of labour without making the distinction. Hence it could not understand the specific character of the unity: abstract labour/concrete labour, and fell into inextricable difficulties. Having thought the distinction, Marx can think the unity. The latter is the result of a social process. The absent cause to which we are referred is the social relations of production.

Thus the formal operations which characterize the space in which economic objects are related together manifest social processes while concealing them. We are no longer dealing with an anthropological causality referred to the act of a subjectivity, but with a quite new causality which we can call metonymic causality, borrowing this concept from Jacques-Alain Miller, who formulated it in the exposition he devoted to the critique of Georges Politzer. Here we can state it as follows: what determines the connection between the effects (the relations between the commodities) is the cause (the social relations of production) in so far as it is absent. This absent cause is not labour as a subject, it is the identity of abstract labour and concrete labour inasmuch as its generalization expresses the structure of a certain mode of production, the capitalist mode of production.1

In other words, the equation: x commodities A = y commodities B is, as we have seen, an impossible equation. What Marx does, and what distinguishes him radically from classical economics, is to theorize the possibility of this impossible equation. Without this theory, classical economics could not conceive the system in which capitalist production is articulated. By not recognizing this absent cause, it failed to recognize the commodity form as ‘the simplest and the most general form’ of a determinate mode of production – the capitalist mode of production. Even if it did recognize the substance labour in the analysis of the commodity, it condemned itself to incomprehension of the more developed forms of the capitalist production process.

In his critique of the starting-point of classical economics, Marx disengages a problem which is that of the mode of manifestation of a certain structure within a space which is not homogeneous with it. We must now make clear the terms of this last problem.

b) The problem of economic objects

Take the commodity-object. Three statements of Marx enable us to define its object character:

1) ‘The products of labour take on the commodity form.’ Here we see that strictly speaking there is not a commodity-object but a commodity-form.

2) The products of labour, when they become values, change into ‘things which transcends sensuousness’ or social things (sinnlich-übersinnlich oder gesellschaftliche Dinge)’ (Vol. 1, pp. 163–4).

3) ‘Commodities possess an objective character as values (Wertgegen-ständlichkeit) only in so far as they are all expressions of an identical social substance, human labour’ (Vol. 1, p. 138).

The question is to define the Gegenständlichkeit of commodities, i.e., their reality as objects.2 The latter is a very special reality. The thingness of commodities is a social thingness, their objectivity an objectivity of value. Elsewhere Marx says that they have a phantasmagoric objectivity. This objectivity only exists as the expression of a social unity, human labour.

We can therefore no longer have a subject-object couple like that of the 1844 Manuscripts. In the Manuscripts, the term Gegenstand was given a sensualist meaning, whereas here it is no more than a phantom, the manifestation of a characteristic of the structure. What takes the form of a thing is not labour as the activity of a subject but the social character of labour. And the human labour in question here is not the labour of any constitutive subjectivity. It bears the mark of a determinate social structure:

It is only a historically specific epoch of development which presents (darstellt) the labour expended in the production of a useful thing as an ‘objective’ (gegenständlich) property of that article, i.e., as its value. It is only then that the product of labour becomes transformed into a commodity (Vol. 1, pp. 153–4).3

It is therefore a ‘historically determined epoch’, i.e., a determinate mode of production, which achieves the Darstellung of labour in the phantasmagoric objectivity of the commodity.

The status of this Gegenständlichkeit is made even clearer when Marx speaks of an illusion of objectivity (gegenständliche Schein):

The belated scientific discovery that the products of labour, in so far as they are values, are merely the material expressions of the human labour expended to produce them, marks an epoch in the history of mankind’s development, but by no means banishes the semblance of objectivity possessed by the social characteristics of labour (den gegenständlichen Schein der gesellschaftlichen Charaktere der Arbeit) (Vol. 1, p. 167).

The character of this Gegenständlichkeit is such that it is only recognized for what it is, i.e., as a metonymic manifestation of the structure, in science. In ordinary perception it is taken for a property of the thing as such. The social character of the products of labour appears as a natural property of these products as mere things.

This theory of the sensuous-supersensuous object enables us to mark the difference between the problematic of Capital and that of the 1844 Manuscripts. In the Manuscripts, economic objects were treated in an amphibological fashion because the theory of wealth was overlaid by a Feuerbachian theory of the sensuous. The sensuous character of the objects of labour referred to their human character, to their status as objects of a constitutive subjectivity. Here objects are no longer taken for anything sensuous-human. They are sensuous-supersensuous. This contradiction in the mode of their appearance refers to the type of objectivity to which they belong. Their sensuous-supersensuous character is the form in which they appear as manifestations of social characteristics.

The substitution of the relationship sensuous/supersensuous → social, for the relationship human/sensuous, is fundamental for an understanding of what Marx calls the fetishism of commodities.

To show this let us examine the beginning of section 4 from the first chapter entitled ‘The Fetishism of the Commodity and Its Secret’: ‘A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties’ (Vol. 1, p. 163).

I think it may be instructive to take this last phrase absolutely to the letter. It means that the commodity is theological in the sense the concept of theology has in the anthropology of Feuerbach and the young Marx. Let us follow this guiding thread in the analysis of the commodity:

In the production of the coat, human labour-power, in the shape of tailoring, has in actual fact been expended. Human labour is therefore been accumulated in the coat. From this point of view the coat is a ‘bearer of value’ (Wertträger), although this property never shows through, even when the coat is most threadbare (Vol. 1, p. 143).

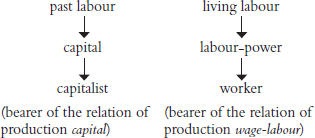

The object is no longer transparent. The whole theory relating the sensuous and the object to the human subject collapses. The coat has a quality which it does not get from the act of a subject, a supernatural quality. It is the bearer (Träger) of something which has nothing to do with it.

Here we have come once again upon the concept of the bearer which we located in the diagram of the anthropological critique of speculation, and with it we return to a function which corresponds to the function of incarnation in this same diagram. The empirical thing (the coat) becomes the bearer of the supernatural abstraction value just as the empirical existence of the monarch became the incarnation of the abstract category ‘sovereignty’ in Hegel.

Nevertheless, the coat cannot represent value towards the linen unless value, for the latter, simultaneously assumes the form of a coat. An individual, A, for instance, cannot be ‘your majesty’ to another individual, B, unless majesty in B’s eyes assumes the physical shape of A (Vol. 1, p. 143).

It is not just because it is a question of majesty here and of sovereignty in the Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law of 1843 that we can affirm the homology between the structure of the manifestation of value and the structure of incarnation which constituted an element of the general structure of speculation in the 1843 text. Value is incarnated in the empirical existence of the coat, just as majesty is incarnated in the empirical existence of A, and sovereignty is incarnated in the empirical existence of the Hegelian monarch.

Thus we see emerging an identical form to that of 1843. But it has neither the critical function that it had in the anthropological critique of speculation, nor the function which the Della Volpe school want it to play as a critique of the speculative operation performed by classical political economy. The union of the sensuous and the supersensuous here expresses the phenomenal form of value itself, and not its speculative translation. In the 1843 Critique this union was presented as a speculative operation. Hegel transformed the sensuous (the empirical) he found at the starting-point so as to make a supersensuous abstraction from it which he then incarnated in a sensuous existence which served as a body for this abstraction.

This means that the pattern which designated the speculative procedure in the anthropological critique, here designates the process which takes place in the field of reality itself. This concept of reality (Wirklichkeit) must be understood to mean precisely the space in which the determinations of the structure manifest themselves (the space of phantasmagoric objectivity). We must carefully distinguish between this Wirklichkeit, real with respect to perception, and the wirkliche Bewegung (real movement) which constitutes the real with respect to science.

We see that the properties which define the Wirklichkeit, the space of appearance of the determinations of the economic structure, are the properties which defined the operations of speculative philosophy for the young Marx. The commodity is theological, i.e., reality is of itself speculative, it itself presents itself in the form of a mystery.

There is another example of this change in function of the structure of incarnation in the text entitled Die Wertform (the first draft of Chapter 1 of Capital):

This inversion (Verkehrung) by which the sensibly-concrete counts only as the form of appearance of the abstractly general and not, on the contrary, the abstractly general as property of the concrete, characterizes the expression of value. At the same time, it makes understanding it difficult. If I say: Roman law and German law are both laws, that is obvious. But if I say: Law (das Recht), this abstraction (Abstraktum) realizes itself in Roman law and in German law, in these concrete laws, the interconnection becomes mystical (‘The Value-Form’, Capital and Class, no. 4, spring 1978, p. 140).

The process which characterizes the mode of existence of value here is the one which characterized the speculative Hegelian operation for the young Marx, and which he illustrated in The Holy Family by the dialectic of the abstract fruit realizing itself in concrete pears and almonds.

If reality is speculative, an extremely important consequence follows: every critical reading which claims, along the lines of the letter to Ruge, to speak or read things as they are, is invalidated. The ambitions of the letter to Ruge are refuted in one short sentence which tells us that ‘Value does not carry what it is written on its forehead’ (Es steht daher dem Werte nicht auf der Stirn geschrieben was er ist).

We are no longer concerned with a text calling for a reading which will give its underlying meaning, but with a hieroglyph which has to be deciphered. This deciphering is the work of science. The structure which excludes the possibility of critical reading is the structure which opens the dimension of science. This science, unlike Ricardo, will not be content to pose labour as the substance of value while deriding the commodity fetishism of the Mercantilists who conceived value to be attached to the body of a particular commodity. It will explain fetishism by theorizing the structure which founds the thing-form adopted by the social characteristics of labour.

Comment 1

A glance at the concepts in action in this problematic of economic objects show us that what is at stake here is the critical question of the Kantian transcendental dialectic. Here too we find the problematic of the object (Gegenstand) and the two couples phenomenon/appearance (Erscheinung/Schein) and sensuous/supersensuous (sinnlich/übersinnlich). In Kant a dividing line relating to the faculties of a subjectivity separates two domains:

| Gegenstand | |

| sinnlich | übersinnlich |

| Erscheinung | Schein |

In Marx we have a quite different structure:

| Gegenstand = Erscheinungsform (form of appearance) | |

| sinnlich-übersinnlich | gesellschaftlich |

| Schein (appearance or illusion) |

The commodity is a Gegenstand in so far as it is the phenomenal form (Erscheinungsform) of value. This object is a sensuous-supersensuous object in so far as its properties are only the form of manifestation of social relations. It is the misrecognition of its supersensuous character, i.e., the misrecognition of its character as a manifestation of labour in a determinate social structure, which founds the appearance (Schein).

In Marx, and particularly here in Chapter 1 of Capital, we do find the relationship between an analytic and a dialectic, but this relationship presupposes a totally new distribution of the elements, a reorganization of the theoretical space of these concepts. We might call this reorganization Marx’s anti-Copernican revolution (anti-Copernican in the Kantian sense, i.e., Copernican in the true sense). Phenomena are no longer centred around a constitutive subject. In the problem of the constitution of the phenomena, the concept of the subject does not intervene. Inversely, what Marx does take seriously is the connection between the phenomenon and the transcendental object = X. The phenomena, the objects, are phenomenal forms of this object, which is also the unknown that resolves the equations. But this X is not an object, it is what Marx calls a social relation. The fact that this social relation has to be represented in something which is radically foreign to it, in a thing, gives that thing its sensuous-supersensuous character. What characterizes appearance (Schein) is the fact that this thing appears in it simply as a sensuous thing and that its properties appear as natural properties.

Thus the constitution of objects does not appertain to a subjectivity. What does appertain to a subjectivity is perception. Appearance (Schein) is determined by the gap between the conditions of constitution of the objects and the conditions of their perception.

Comment 2

What radically differentiates Marx from classical economics is his analysis of the value-form of the commodity (or the commodity-form of the product of labour). The difference between the classical conception of abstraction and analysis and the Marxist conception is inscribed here. The theory of the form provides a solution at the level of the specific theoretical practice of Capital to the problems raised in the 1857 Introduction by the concept of determinate abstraction.4

The historicist interpretation of this theory of determinate abstraction as it is found particularly in the Della Volpe school depends upon a non-pertinent relation; the relation between the abstract in thought and the real concrete. The determinate abstraction then appears to be the one which solidly preserves the richness of the real concrete.

Marx, on the other hand, is concerned here with the value-form of the commodity (the commodity-form of the product of labour) as a scientific starting-point within the thought process. From this viewpoint, the value-form is characterized as the most general, the simplest, the most abstract, and the least developed form. Here I shall not speak of the first of these determinations, which incidentally poses difficult interpretation problems. Simple and abstract are situated in the oppositions abstract/concrete and simple/complex which define the field of what is thought in the 1857 Introduction. But the meaning of these two oppositions is made clearer here by the concept of development. This form is the least developed and the task of science, a task which was never undertaken before Marx, is to develop this simple form:

Now, however, we have to perform a task never even attempted by bourgeois economics. That is, we have to show the origin of this money-form, we have to trace the development of the expression of value contained in the value-relation of commodities from its simplest, almost imperceptible outline to the dazzling money-form (Vol. 1, p. 139).

Ricardo was incapable of making this development. He was incapable of deducing the money-form from his theory of value. This was because he did not grasp the concept of the expression of value, the concept of form. What he missed in this way was the motor of the development of the economic categories, a development which permits the constitution of the system of political economy. This motor is contradiction.

This poses the problem of the location of the concept of contradiction, the problem of the determination of its theoretical validity.

What is it that Marx, in the first chapter of Capital, calls sometimes contradiction (Widerspruch) and sometimes merely opposition (Gegensatz)? There can be no question of providing a definitive solution to this problem here, but only of presenting certain givens and indicating a possible direction for enquiry.

Take the relationship: x commodities A = y commodities B. It can be said to be contradictory in so far as one of the terms appears only as use-value and the other only as exchange-value. This contradiction refers to the internal contradiction of the commodity, to its duplication into use-value and exchange-value, and from here we are referred to the identity of opposites which characterizes the labour represented in the value-form of the commodity – the identity of concrete labour and abstract labour.

Three comments can be made here.

1) The contradiction posed here cannot be reduced to the order of appearance and ideology, as was the case with the pseudo-contradiction in adjecto implied, according to Bailey, by the concept of an exchange-value intrinsic to a commodity. On the contrary, this contradiction only occurs in the scientific discourse. It is not perceived by the subjects of the exchange, for whom the relation xA = yB is quite natural.

2) It does not consist of a split. In the equations in the 1844 Manuscripts which expressed the contradiction, the latter amounted to the separation of an original unity. The contradiction lay in the separate existence of complementary terms. Here, on the contrary, it lies in the union of two mutually exclusive terms. This identity of two opposites exposes the hidden existence of a third term which supports their union, i.e., of the term social, which supports the sensuous-supersensuous contradiction.

3) Nor does the contradiction consist of the fact that concrete labour is inverted into abstract labour, in the way that, with Hegel, Being is inverted into Nothingness, or the concrete here-now into the abstract universal. The contradictory union of concrete labour and abstract labour is not determined by a dialectic supposed to be inherent in one of these two terms. It expresses the special form that the general characteristics of labour take in a determinate mode of production.

Marx shows in fact that all production is necessarily determined by the society’s available labour time and by the distribution of social labour according to the different needs.5 This rule must be observed in one way or another in all forms of production. But it adopts different characteristics in each of these forms. Thus, in the text on the fetishism in Chapter 1, Marx shows in the case of several different forms of production (Robinson Crusoe, the Middle Ages, patriarchal peasant industry, and finally communist society) how this natural law operates according to specific forms determined by each of these structures. Within the capitalist mode of production, where commodity production is the dominant form of production, the regulatory law of labour time and its distribution follows a very special pattern, that of the contradictory identity of concrete labour and abstract labour, represented in the inherent contradictions of commodity exchange.

‘Contradiction’ could thus well designate precisely the structure’s peculiar mode of effectivity. We have already seen that the space of representation (Darstellung) of the structure was a space of contradiction, in which the objects were not objects, in which the relations linked together things which did not have any relationship between them, etc. The existence of the contradiction thus appeared as the very existence of the structure. In this way we should perhaps give the concept of contradiction, as Marx uses it in Part One of Capital, a purely indexical value; i.e., in these Hegelian concepts ‘contradiction’ and ‘development of the contradiction’, Marx is thinking something radically new, the concept of which he has not succeeded in formulating – the mode of action of the structure as a mode of action of the relations of production which govern it.

Recognition of the contradiction is thus recognition of the structure within which the economic objects and their relations function, the structure of a determinate mode of production. By analysing the commodity form Marx discovered the contradiction, i.e., he discovered that economic objects were determined as manifestations of a particular structure. The development of the forms is thus a development of the contradiction. The resolution (Lösung) of the contradiction is achieved in what Marx calls its forms of movement. The more complex, more developed forms are forms in which the contradictions of the simpler forms can develop and resolve themselves. This is the case for forms of exchange with respect to the contradictions inherent in the commodity form, and for the forms of capitalist production with respect to the forms of simple commodity production:

We saw in a former chapter that the exchange of commodities implies contradictory and mutually exclusive conditions. The further development of the commodity [as something with a double aspect, use-value and exchange-value] does not abolish these contradictions, but rather provides the form within which they have room to move. This is, in general, the way in which real contradictions are resolved. For instance, it is a contradiction to depict one body as constantly falling towards another and at the same time constantly flying away from it. The ellipse is a form of motion within which this contradiction is both realized and resolved (Vol. 1, p. 198).

There is an antithesis, immanent in the commodity, between use-value and [exchange-]value, between private labour which must simultaneously manifest itself as directly social labour, and a particular concrete kind of labour which simultaneously counts as merely abstract universal labour … these contradictions immanent in the commodity acquire their forms of motion in circulation (Vol. 1, p. 209; translation modified according to the French edition, t. 1, p. 122).

The development of the forms of bourgeois production, which constitutes the object of Capital proper, is thus thought as the development of forms of motion for the primitive contradiction, the opposition between abstract labour and concrete labour. Here, too, we can ask whether the concepts used by Marx (contradiction, development, resolution of contradiction) adequately express what is thought in them.

Let us leave this problem in abeyance and note the two essential elements that we have been able to extract from the analysis of the value-form:

1) This analysis and the theory of the form which it implies enable us to bring to light the constitutive structure of the relations of production and its mode of action at the level of Wirklichkeit.

2) It enables us to attain a systematic knowledge of the connection and articulation of the forms of the capitalist mode of production. Classical economics was unable to handle this development of forms. (For example, Ricardo did not succeed in deducing money from the analysis of the commodity or in showing the connection between surplus-value and the average rate of profit.)

We shall find that these two elements become clearer when we turn to the study of a special commodity – wage-labour.

c) Wage-labour and the theory of the irrational

It is well-known that the category of wage-labour poses an insoluble problem for classical economics. What really happens in the exchange between the capitalist and the worker?

The capitalist buys a certain quantity of labour, the worker’s working day, with a wage which represents a smaller quantity of social labour. We therefore see two commodities which represent unequal social labour times exchanged as equals, which clashes with the labour theory of value.

At the same time, we discover a circle. The wage appears to be the value of the labour. But labour has been posited as the creator of value. How can one determine the value of what creates value?

The solution to this clash and to this circle lies in the introduction of a new category, absent from classical economics, the category of labour-power.

The wage represents the value of labour-power. This value as we know, in accordance with the law of value, represents the value of the means of subsistence necessary for the reproduction of labour-power. Classical political economy had indeed formulated this determination of the value of labour-power, but as the value of labour. It therefore remained in a quid pro quo.

In the 1844 Manuscripts, Marx, too, remained in this quid pro quo, tied to the non-critique of the concept of the value of labour and of the concept of labour itself. Here, on the contrary, Marx attacks the concept itself and with the help of the concepts of form and relation works it over so that a new concept appears, that of labour-power, so that the concept of the value of labour can be understood in its inadequacy.

Marx grasped the difference between the exchange-value of labour-power (the quantity of social labour necessary for its reproduction, represented in wages) and its specific use-value – to create value.

We can pose the problem in the following two statements:

1) Labour-power has an exchange-value measured by the labour time necessary for its reproduction, and a use-value which is creative of value, which produces an exchange-value greater than its own value (which is not true of any other commodity).

2) Labour is creative of value. It does not have value.

In these two statements we can read the possibility of surplus-value. We can do so thanks to the analysis of the double character of labour, of the distinction between useful labour and labour creative of value, which enables us to penetrate the appearance of the capitalist mode of production:

From all appearances, what the capitalist pays for is the value of the usefulness which the worker gives him, the value of the labour and not that of the labour-power which the worker does not seem to alienate. The experience of practical life alone does not bring out the double usefulness of labour, the property of satisfying a need which it has in common with all commodities, and the property of creating value which distinguishes it from all the other commodities and, as a formative element of value, prevents it from having any value itself (Le Capital, Livre 1, t. II, p. 211; the English edition, Vol. 1, p. 681 reads differently).

We are confronted with the following contradiction: labour appears as a commodity whereas it cannot ever be a commodity. That is, we are dealing with a structure which is impossible. This possibility of an impossibility refers us to the absent cause, to the relations of production. The immediate producers, separated from their means of production as a result of primitive accumulation, are constrained to sell their labour-power as a commodity. Their labour becomes wage-labour and the appearance is produced that what is paid for by the capitalist is their labour itself, and not their labour-power.

The revelation of the category ‘value of labour-power’ concealed behind the category ‘value of labour’ is the revelation of the determinant character of capitalist relations of production.

Unable to problematize the category ‘value of labour’ as a phenomenal form of the value of labour-power, Ricardo could not reveal what sustains the whole mechanism, i.e., the relations of production: capital and wage-labour:

Instead of labour, Ricardo should have discussed labour capacity. But had he done so, capital would also have been revealed as the material conditions of labour, confronting the labourer as power that has acquired an independent existence? And capital would at once have been revealed as a definite social relationship. Ricardo thus only distinguishes capital as ‘accumulated labour’ from ‘immediate labour’. And it is something purely physical, only an element in the labour process, from which the relation between labour and capital, wages and profits, could never be developed (Theories of Surplus-Value, MECW 32, p. 36).

Marx, on the other hand, problematizes the category ‘value of labour’. This expression is an imaginary expression. In Marx this category of the imaginary designates the posing of an impossible relation which conceals the truly determinant relation.

There is a naive way of thinking the imaginariness of this expression. This is to consider it as a mere abuse of language. Thus Proudhon states that, ‘Labour is said to have value not as a commodity itself, but in view of the values which it is supposed potentially to contain. The value of labour is a figurative expression’ (cit. Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, p. 677 n6). Thus, according to Proudhon, the whole world of capitalist production is founded on a ‘figurative expression’, mere poetic licence. Here we have a very characteristic type of explanation; confronted by expressions which designate the mystery of capitalist production, its fundamental structural determination, it is said that these constitute only figurative expressions or subjective distinctions. In Capital, Marx repeatedly calls attention to this type of explanation by the arbitrary and subjective. (Ricardo, for example, states that the distinction between fixed and circulating capital is a wholly subjective one.)

For Marx, on the contrary, the imaginary expressions are not at all arbitrary. They express a rigorous necessity; that of the mode of action of the relations of production:

In the expression ‘value of labour’, the concept of value is not only completely extinguished, but inverted, so that it becomes its contrary. It is an expression as imaginary as the value of the earth. These imaginary expressions arise, nevertheless, from the relations of production themselves. They are categories for the forms of appearance of essential relations (Sie sind Kategorien für Erscheinungsformen wesentlicher Verhältnisse) (Vol. 1, p. 677).

Here the theory of the form and of the development of forms acquire precision. The expression ‘value of labour’ presupposes a change of form; the value of labour-power appears, manifests itself in a form of manifestation (Erscheinungsform) which is the value of labour. As a form of manifestation of labour-power, the value of labour is a form of manifestation of that relation of production essential to the capitalist mode of production – wage-labour. The mechanism of transformation of the forms is thus determined by the relations of production, which manifest themselves in the Erscheinungsformen by concealing themselves. The imaginariness is the index of this peculiar effectivity, this manifestation/concealment of the relations of production:

We may therefore understand the decisive importance of the transformation of the value and price of labour-power into the form of wages, or into the value and price of labour itself. All the notions of justice held by both the worker and the capitalist, all the mystifications of the capitalist mode of production, all capitalism’s illusions about freedom, all the apologetic tricks of vulgar economics, have as their basis the form of appearance discussed above, which makes the actual relation invisible, and indeed presents to the eye the precise opposite of that relation (Vol. 1, p. 680).

d) The concept of process

In the study of the phantasmagoric objectivity of commodities and in that of the imaginary expression ‘value of labour’, a certain structure can be apprehended. We see that the forms of Wirklichkeit are forms of manifestation for the social relations of production which do not appear as such in this field of Wirklichkeit but which structure the relations given there. At the same time, we see that all these forms of manifestation are equally forms of concealment. It is this structure which is misrecognized by classical economics. In the absence of a theory of form it misrecognizes its own object. It does not recognize the specific objectivity with which science is concerned, that of a determinate process of production.

For an understanding of this concept ‘process’, let us first recall Marx’s definition: ‘The word process … expresses a development considered in the totality of its real conditions’ (Capital, Vol. 1, p. 685, modified according to the French edition).

Let us complete this definition by mentioning the two essential characteristics of a process, i.e.:

1) its development leads to a constant reproduction of its starting-point;

2) the elements in it are defined not by their nature but by the place they occupy, the function they fulfil.

These characteristics are valid even for the simplest process studied by Marx, the labour process in general. Marx shows that the same material elements can play the part of product, raw material or means of labour in the labour process:

Hence we see that whether a use-value is to be regarded raw material, as instrument of labour of as product is determined entirely by its specific function in the labour process, by the position it occupies there: as its position changes, so do its determining characteristics (Vol. 1, p. 289).

A confusion is already possible at this level, a confusion between a material property of the elements of production and their functional determination. But we know in fact that the production process always takes place in determinate social forms, that it is always a determinate production process. This means that the places, forms and functions which it determines must themselves serve as bearers for those which are determined by the relations of production characterizing some mode of production. These relations of production in fact determine new places and functions which give specific forms to the elements of the labour process. In Wirklichkeit, these forms appear as properties of the material elements which support them, whereas they are phenomenal forms, modes of existence of the hidden motor of the development. The same is true of the commodity form which, in the fetishistic illusion, is severed from the social relations which found it, and of the form ‘value of labour’ behind which is hidden the value of labour-power, i.e., the capitalist relations of production.

This structure of the process of science implies the specific character of the concepts of the science which explains it. This is expressed by Marx in an opposition which determines the true form of scientificity on the one hand, and the principle of the errors of classical economics, on the other. ‘What is at issue here is not a set of definitions under which things are to be subsumed. It is rather definite functions that are expressed in specific categories’ (Capital, Vol. 2, p. 303).

| Things (Dinge) | Functions |

| subsume | express |

| definitions | categories |

Believing that it deals with natural relations between stable things, classical economics misrecognizes the specific structure of the capitalist process of production. In fact the latter is constituted by the concealment of the process of production in general, of the form of commodity production, and of the forms peculiar to the capitalist process which itself develops at several levels (production, reproduction, overall process). Classical economics, which flattens this structure down to a single plane, is trapped in a whole series of confusions: a confusion of the material determinations of the elements of production with the capitalist forms of these determinations; a confusion between forms of simple commodity production and capitalist forms; confusions between the forms of capital in the production process and in the circulation process, etc. Smith’s conception of fixed and circulating capital, criticized by Marx in Volume Two, is a concentrate of all these confusions. Smith succeeds in reducing the determinations of fixed and circulating capital, determinations of the form of the capital involved in the circulation process, to the mobility or immobility of the material elements of capital.

Thus we see how the study of the starting-point of Capital leads us to recognize the peculiar objectivity with which science is concerned, and to understand the basis of the errors of classical economics.

Appendix – Commodity relations and capitalist relations

Our analysis of the value-form raised the following objection. In order to explain the identity abstract labour/concrete labour which determines the value-form of commodities, we introduced the capitalist relations of production. Now it is evident that the commodity form existed long before the capitalist mode of production, and it seems that the analysis made of the commodity in the first part of Capital only introduces the characteristics of commodity production in general, independently of the part this form of production may play in different modes of production.

First let me restrict the range of the objection. It does not contradict at all what seems to me to be the fundamental point, namely the fact that the phenomena of economic reality (Wirklichkeit) are only comprehensible in so far as they manifest, in a specific distortion, the effectivity of the relations of production. However, what is at issue is the exact meaning of the function that the analysis of the commodity plays in the theory of the capitalist process of production, the function of the starting-point.

In fact, it seems at first that in Capital Volume One, Part One it is only a question of commodity production in general, in so far as it is a necessary presupposition of the capitalist mode of production. Thus we are concerned with the commodity in general and not with the commodity as an element of a capital commodity. The identity of useful labour and labour creative of value simply defines commodity production, capitalist production being defined by the identity of useful labour and labour creative of surplus-value.

In this first part we should thus be at a stage (theoretically and historically) prior to the peculiar determinations of the capitalist mode of production. Given this, a historicist reading is possible, one which sees in the first part a genetic exposition moving from primitive forms of exchange to bourgeois forms via those commodity islands which develop, as Marx puts it, in the interstices of societies prior to the capitalist mode of production.

But at the same time, Marx tells us that ‘the value-form of the product of labour is the most abstract, and but also the most universal form of the bourgeois mode of production; by that fact it stamps the bourgeois mode of production as a particular kind of social production of a historical and transitory character’ (Vol. 1, p. 174 n35), and he affirms in a letter to Engels dated 22 June 1867 that the simplest form of the commodity ‘embodies the whole secret of the money form and thereby, in nuce, of all bourgeois forms of the product of labour’ (MECW 42, p. 384). The metaphor of the embryo, like that of the cell in the Preface to the first German edition, indicates that the peculiar determinations of the capitalist mode of production are not simply added on over and above the simple determinations of the commodity and the exchange of commodities, but must in some way be already present in them. If so, we should have in the first chapter of Capital not at all an analysis of the general characteristics of all commodities but an analysis of the commodity form in so far as it is the simplest form of a determinate mode of production, the capitalist mode of production.

The accuracy of such an interpretation is clearly confirmed by Marx’s praise of Steuart in the first chapter of A Contribution:

Steuart knew very well that in pre-bourgeois eras also products assumed the form of commodities and commodities that of money; but he shows in great detail that the commodity as the elementary and primary unit of wealth and alienation as the predominant form of appropriation are characteristic only of the bourgeois period of production, and that accordingly labour which creates exchange-value is a specifically bourgeois feature (MECW 29, p. 298).

However, we must avoid the trap of a Hegelian reading of Capital, according to which the commodity form contains in embryo, in its interiority, all the contradictions of the capitalist mode of production, of which capital is only the development – with the corollary, inevitable in a discourse of the Hegelian type, that this starting-point is itself mediated by the destination point, that the commodity presupposes the whole development of the capitalist production process.

Note that Marx provides at least as many arguments for this Hegelian interpretation as he does for the historicist interpretation, and let me show the way I believe the problem can be posed correctly. To do so I can draw on the indications that Marx gives us in the chapter in Volume Three entitled ‘Relations of Distribution and Relations of Production’:

[Capitalist production] produces its products as commodities. The fact that it produces commodities does not in itself distinguish it from other modes of production; but that the dominant and determining character of its product is that it is a commodity certainly does so. This means, first of all, that the worker himself appears only as a seller of commodities, and hence as a free wage-labourer, i.e., labour generally appears as wage-labour (Vol. 3, p. 1019).

What is also implied already in the commodity, and still more so in the commodity as the product of capital, is the reification of the social determinations of production and the subjectification (Versubjektifierung) of the material bases of production which characterize the entire capitalist mode of production (p. 1020).

[T]he particular form in which social labour-time plays its determinant role in the value of commodities coincides with the form of labour as wage-labour, and the corresponding form of the means of production as capital, in so far as it is on this basis alone that does commodity production become the general form of production (p. 1022).

Only on the basis of the capitalist relations of production does the form of commodity production become the dominant form of production and the commodity form appear in a general way and with all the determinations to which it is susceptible as a form of the product of labour. Or, to put it another way, the identity of useful labour with labour creative of value only determines social production overall on the basis of the identity of useful labour and labour creative of surplus-value.

This confirms the determinant character of the capitalist relations of production.

Given the separation of immediate producers and means of production, the conversion of the means of production into capital, achieved in the process of the constitution of the capitalist mode of production (‘primitive accumulation’), the useful labour of the worker, of the immediate producer, can be manifested only as labour creative of value. This creates the condition which allows the identity of useful labour and labour creative of value to become the general law of production. It is in this way that the characteristics of the capitalist mode of production can be found already implied (eingeschlossen) in the simple commodity form of the product of labour.

(2) Structure of the Process and Perception of the Process

a) The development of forms and the inversion

We have established a first concept expressing the relation between the internal determination of the process and its forms of appearance (or forms of manifestation) – the concept of concealment. In doing so, we have provisionally left in the shade a second concept which defines this relation – the concept of inversion (Verkehrung).

Studying the change in form which converts the value of labour-power into value of labour, Marx declares: ‘[this] form of appearance … makes the actual relation invisible, and indeed presents to the eye the precise opposite of that relation’ (Vol. 1, p. 680). ‘In the expression “value of labour”, the concept of value is not only completely extinguished, but inverted, so that it becomes its contrary’ (Vol. 1, p. 677).

What does this inversion consist of? What appears in the form of wages is the fact that the worker is paid for the whole of his working day without distinction, whereas in reality the wages correspond to the value of the labour-power, and therefore to the part of the working day during which the worker reproduces the value of his own labour-power. In the form of wages, the basis for the understanding of surplus-value (the division of the working day) is thus reversed.

One of the essential points of the revolution brought about by Marx in political economy consists of his bringing to light in its domain this connection of inversion between scientific determination and phenomenal form, which is for him a general law of scientificity. ‘That in their appearance things are often presented (sich darstellt) in an inverted way is something fairly familiar in every science, apart from political economy’ (Vol. 1, p. 677).

The inversion of the inner structural determinations, which bear witness to the constitutive character of the relations of production, in their forms of manifestation, thus appears as a fundamental characteristic of the process. It is this law which determines the development of its forms.

We already have an illustration of this even at the level of mere monetary circulation. Money is in fact a form of existence of the value of commodities and monetary circulation a form of motion for the contradictions in commodities. But an examination of the movement of circulation as it is given in ordinary experience reveals a different presentation:

The circulation of money is the constant and monotonous repetition of the same process. The commodity is always in the hands of the seller; the money, as a means of purchase, always in the hands of the buyer. And money serves as a means of purchase by realizing the price of the commodity. By doing this, it transfers the commodity from the seller to the buyer, and removes the money from the hands of the buyer into those of the seller, where it again goes through the same process with another commodity. That this one-sided form of motion of money arises out of the two-sided form of motion of the commodity is a circumstance which is hidden from view. The very nature of circulation itself produces a semblance of the opposite … As means of circulation, money circulates commodities, which in and for themselves lack the power of movement, and transfers them from hands in which they are non-use-values into hands in which they are use-values; and this process always takes the opposite direction to the path of the commodities themselves. Money constantly removes commodities from the sphere of circulation, by constantly stepping into their place in circulation, and in this way continually moving away from its own starting-point. Hence although the movement of the money is merely the expression of the circulation of commodities, the situation appears to be the reverse of this, namely the circulation of commodities seems to be the result of the movement of the money (Vol. 1, pp. 211–2).

Here Marx distinguishes between two motions: a real motion which is the movement of value, a movement which is concealed in the repetition of the process of circulation, and an apparent motion, a movement accredited by everyday experience, and which presents the inverse of the real motion.

We find that this relation of inversion is confirmed as we pass from the most abstract and least developed forms of the capitalist process to its most developed and most concrete forms. It is the development of these ‘concrete forms which grow out of the process of capital’s movement considered as a whole’ (Vol. 3, p. 117), forms determined by the unity of the production process and the circulation process in the process of capital as a whole, that forms the object of Volume Three of Capital. This development ends with the forms which are manifest at the surface of capitalist production, those in which different capitals confront one another in competition, and which are perceived in their daily experience by the economic subjects to whom Marx gives the name of agents of production.

The development of the forms of the process is thus governed by the law of inversion; the forms in which the process of capitalist production presents itself or appears are rigorously inverted with respect to its inner determination. They present a connection of things (Zusammenhang der Sache) which is the inverse of the inner connection (innere Zusammen-hang), an apparent motion which is the inverse of the real motion of capitalist production. It is this form of the apparent motion or of the connection of things which is given to the perception of the agents of production.6

We shall study this law in a precise example – the theory of the ‘grounds for compensation’ expounded by Marx in Volume Three (pp. 310ff.). However, before beginning our study of this text, I must first make two preliminary remarks.

1) The analysis of the grounds for compensation presents the application of the following passages from Volume One:

The general and necessary tendencies of capital must be distinguished from their forms of appearance. While it is not our intention to consider the way in which the immanent laws of capitalist production manifest themselves in the external movement of the individual capitals, assert themselves as the coercive laws of competition, and therefore enter into the consciousness of the individual capitalist as the motives which drive him forward, this much is clear: a scientific analysis of competition is possible only if we can grasp the inner nature of capital, just as the apparent motions of the heavenly bodies are intelligible only to someone who is acquainted with their real motions (Vol. 1, p. 433).

In the relation between these three terms – tendencies immanent to capitalist production (real motion), movements of individual capitals (apparent motion), and the motives of the capitalists – we can see the outline of a theory of capitalist subjectivity, a theory of motors and motives, completely different from that of the 1844 Manuscripts. It is not the motives of the capitalist that turn against him in the form of objectivity; it is the tendencies specific to capital, the structural laws of the capitalist mode of production, that, through the phenomena of competition, are internalized as motives by the capitalists.

In Volume One this problem could only be posed incidentally. In Volume Three, on the contrary, the analysis of the inner nature of capital reaches the point where Marx is able, without analysing competition in itself, to pose the basis for such an analysis – the determination of the relation between real motion and apparent motion.

2) The analysis of the grounds for compensation is a part of the study of the equalization of the rate of profit through competition. Its understanding demands that we recall the broad outlines of the transition from surplus-value to profit and the establishment of an average rate of profit.

i) Surplus-value and profit

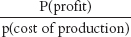

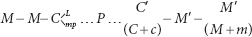

Let us start with the formula c (constant capital) + v (variable capital) + s (surplus-value), which expresses the value of commodities. We derive from it the rate of surplus value = s/v. The formula s/v expresses what Marx calls the conceptual connection. In fact it expresses the origin of surplus-value as the ratio of unpaid to paid labour.

At the level of the concrete phenomena of the process of capital as a whole, surplus-value does not appear. What does appear is a form of appearance of surplus-value – profit. Like all forms of appearance, profit is at the same time a form of concealment. In fact, what is considered in it is no longer the conceptual connection of surplus-value with variable capital, but its a-conceptual (begriffslose) connection with the whole of capital, a connection in which the differences between the component elements disappear. In which, therefore, according to Marx, ‘the origins of surplusvalue and the mystery of its existence’ are obliterated.

The rate of profit is expressed by the formula

which in reality represents s/v, the mass of profit being equal to the mass of surplus-value and the sum c + v determining the cost of production.

ii) The establishment of the average rate of profit

Unlike the rate of surplus-value, the rate of profit is determined by variations of constant capital. Independently of the rate of surplus-value and the mass of profit, the rate of profit will vary as a function of the lesser or greater importance of constant capital in relation to variable capital (which alone produces surplus-value).

If a capital has an organic composition lower than the average, i.e., if the proportion of constant capital in it is lower than the average, then the rate of profit will increase, and vice versa.

In a situation of perfect competition, there will be a flow of capital towards the spheres in which the rate of profit is higher than the average. This inflow of capital will induce an expansion of supply in relation to demand and vice versa in the spheres from which the capital has been withdrawn. Thus an equilibrium will be established:

This constant migration, the distribution between the various spheres according to where the rate of profit is rising and where it is falling, is what produces a relationship between supply and demand such that the average profit is the same in the various different spheres, and values are therefore transformed into prices of production (Vol. 3, p. 297).7

As a consequence, capitals of the same size will yield equal profits, independently of their organic compositions. The law of value is thus overturned, or, more accurately, it is realized in the form of its opposite. But this determination by the law of value is known only by science. The forms of competition in which it is realized conceal it. This is what Marx shows in the passage on the grounds for compensation:

What competition does not show, however, is the determination of values that governs the movement of production; that it is values that stand behind the prices of production and ultimately determine them (Vol. 3, p. 311).

On the contrary, competition does show three phenomena which go against the law of value:

1) The existence of average profits independently of the organic composition of the capital in the various spheres of production, and therefore of the mass of living labour that a capital expropriates in a determinate sphere;

2) The rise and fall of prices of production consequent on a change in wages;

3) The oscillation of market prices around a market price of production different from the market value:

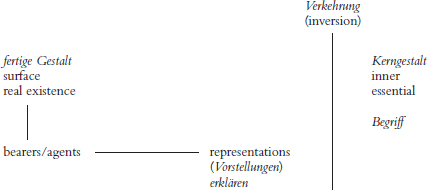

All these phenomena seem to contradict both the determination of value by labour-time and the nature of surplus-value as consisting of unpaid surplus labour. In competition, therefore, everything appears upside down. The finished configuration (fertige Gestalt) of economic relations, as these are visible on the surface, in their actual existence, and therefore also in the notions with which the bearers and agents of these relations seek to gain an understanding of them, is very much different from the configuration of their inner core (Kerngestalt), which is essential but concealed, and the concept (Begriff) corresponding to this (ibid.).

We have in this passage the elements of a theory:

– of the structure of the process;

– of the place of the subject in that structure;

– of the possibility of ideological discourse and its difference from science.

Let us put the relevant terms together in a general table. We can complement this table with a certain number of equivalent terms. The level of the fertige Gestalt is also that of the connection of things, of the apparent motion and of reality (Wirklichkeit). The level of the Kerngestalt is that of the inner connection and of the real motion.

To start with, this table enables us to specify the concept of science. In order to do this, let us recall the passage which defined classical economics as a science:

Classical political economy seeks to reduce (zurückführen) the various fixed and mutually alien forms of wealth to their inner unity (innere Einheit) by means of analysis and to strip away the form in which they exist independently alongside one another. It seeks to grasp (begreifen) the inner connection in contrast to the multiplicity (Mannigfaltigkeit) of outward forms (Erscheinungsformen) (Theories of Surplus-Value, MECW 32, p. 499).

We noted that in this project of classical political economy the dimension of science was installed by the establishment of a difference whose concept was not thought. Let us try to look more closely at why it was not, by examining the system of terms which in our text define the operation of begreifen, the pattern of the Begriff.

| zurückführen | Mannigfaltigkeit |

| Einheit | Erscheinungsformen |

It is a question of the reduction to a unity of the multiplicity of phenomenal forms, which defines a Kantian-style project. By utilizing this Kantian vocabulary, Marx designates a certain type of relationship between the science and its object of investigation, which in the Theories of Surplus-Value he characterizes as formal abstraction, false abstraction, insufficient abstraction.