Let us make our own intensions crystal clear. We must and we will be free. We want freedom now. We do not want our freedom fed to us in teaspoons over another one hundred fifty years. Under God we were born free. Misguided men robbed us of our freedom. We want it back.

— Martin Luther King Jr., from a speech given at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference Crusade for Citizenship, February 12, 1958.

The trade in African peoples began in 1441 with the development of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, a complex international economic system operated by European merchants. Portugal was the first European country to establish the trafficking of Africans followed by Spain, Holland, and France. Britain entered the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1562 and became the leading slave-trading power by the early 1700s. Ships from Europe brought horses, guns, cutlery, fabrics, copper, and alcohol to West Africa to exchange for captive Africans who were then transported across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World, on the horrific Middle Passage, along with African products such as ivory, gold, palm oil, spices, and animal skins. Africans were forced to work as household servants and on plantations and farms to produce massive quantities of sugar, cotton, rice, tobacco, coffee, and rum that were shipped back to Europe and sold. All of these goods traded in the Transatlantic Slave Trade moved across the Atlantic Ocean in the shape of a triangle and became the foundation of the flourishing economies of these European nations — all based on the successful trade in African bodies.

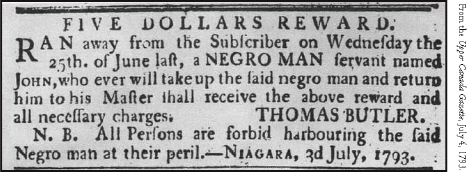

Advertisements were used by slave owners to deter the public from assisting runaway slaves.

The participating European powers wanted to increase their wealth, power, and size through the expansion of new colonies in the Caribbean, South America, the United States, and Canada, and believed this could be accomplished by utilizing a large pool of cheap labour. Africans were kidnapped, sold, bought, and traded as chattel goods for the purpose of providing free labour as farm hands, domestics, and many other skilled and unskilled positions. By the time the Transatlantic Slave Trade was deemed illegal by Britain in 1807 and the United States in 1808, over twenty million Africans had been captured or purchased from Africa and almost ten million died in the Middle Passage. Although the transportation of Africans across the Atlantic Ocean was banned, the practice of slavery continued, but not without constant opposition from those who were held in bondage. Enslaved Africans resisted their slave status from the moment they were taken from Africa by revolting on slave ships, refusing to eat, and committing suicide rather than suffer along the Middle Passage. Some political leaders on the continent of Africa — kings, queens, and chiefs — also fought against the enslavement of their people by taking various measures to halt the trade of Africans.

In the Western world, slaves protested their conditions in their daily lives including breaking tools, working slowly, leaving for short periods of time, running away, obtaining an education, and practising African cultural traditions. A dramatic act of resistance was committed by Marie-Joseph Angélique, an enslaved Portuguese woman of African descent in Montreal, who allegedly set fire to her owner’s house to protest her pending sale. In total, forty-seven buildings burned down. Immediately after, she was tried, found guilty, tortured, and hanged for her alleged crime of contestation.1 Taking slave masters to court was another kind of resistance enslaved Blacks employed, which in Canada, with the support of anti-slavery judges, was a key mechanism in the attack and destruction of slavery. For example, in 1899 an enslaved woman in New Brunswick named Nancy Morton legally disputed her masters’ ownership rights.2 Enslaved Africans also engaged in large-scale resistance schemes. In fact, continuous slave-led armed rebellions were instrumental catalysts in the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, largely because slave owners were incurring too many expenses for slaveholding to remain lucrative.

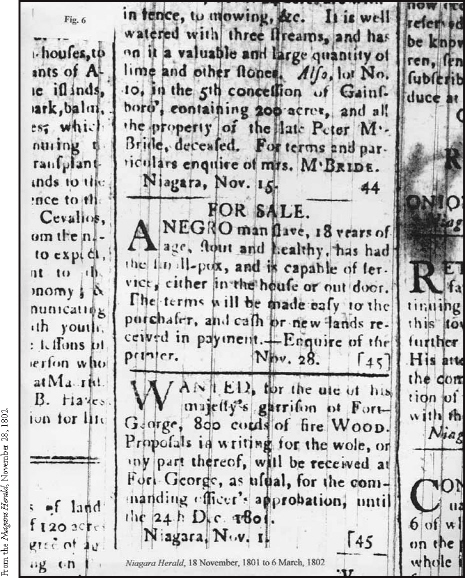

People of African descent continued to be enslaved after the passage of the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery.

In the Haitian Revolution, hundreds of slaves on the island of Saint Domingue, the portion that is now Haiti, were led by Toussaint L’Overture in an uprising against the French in a fierce, long battle, which lasted from 1791 to 1804. The captive resistors were victorious and Haiti was established, the first independent Black country outside of the African continent. After this long, gruelling fight, colonial powers began to recognize the economical, political, and military threats of such insurrections, a factor that was influential in outlawing the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Revolts also happened in the United States under such leaders as Gabriel Prosser in Virginia in 1800, Denmark Vesey in South Carolina in 1822, and Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831. Caribbean revolts included the four-month long Sam Sharpe Rebellion in Jamaica, also in 1831. Two British Guiana (now Guyana) revolts included the Berbice Slave Rebellion in 1762 and one in Demerara in 1795. Grenada and St. Vincent also had slave uprisings in 1795, and Brazil was the site of the Bahia Rebellion in 1835.

The abolition movement gained momentum and international attention through the persistent agitation of enslaved men and women throughout North America, South America, Europe, and the Caribbean, combined with the varied contributions of Black abolitionists, such as self-emancipated slaves Olaudah Equiano,3 Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass.4 White anti-slavery activists such as Toronto newspaper editor George Brown, Belleville doctor and ornithologist Alexander Ross, the St. Catharines politician, architect, and engineer William Hamilton Merritt, the Ohio Quaker Levi Coffin, and British abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson were also champions of the cause.

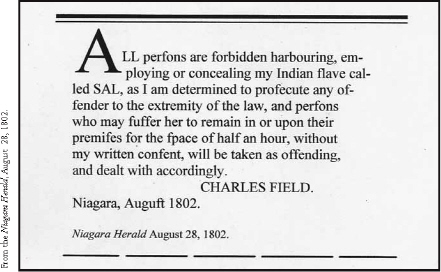

Native people comprised a large percentage of the slaves owned in Canada.

Canada was not only involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the enslavement of Africans, but would eventually be the first British territory to adopt legislation leading to the eradication of slavery. To this day, it is still not common historical knowledge in Canada that Africans were enslaved in both the French and British colonies from as early as 1628.5 Furthermore, very few Canadians are aware that at one time their nation’s economy was firmly linked to African slavery through the building and sale of slave ships, the sale and purchase of slaves to and from the Caribbean, and the exchange of timber, cod, and other food items from the Maritimes for West-Indian slave-produced goods such as rum, tobacco, cotton, coffee, molasses, and sugar.

However, in 1793, the wheels for the abolition of slavery in British possessions starting turning in Upper Canada with the passage of the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery. Lieutenant-Governor John Grave Simcoe, an ardent abolitionist, introduced a bill to end the practice of slavery, but was met by resistance from his slave-holding cabinet members who instead opted for a compromise of a gradual end to this inhumane institution.6 This first piece of abolition legislation titled, “an Act to prevent the further introduction of slaves, and to limit the term of contract for servitude within this province,” outlined that the importation of slaves into Upper Canada was banned immediately, but those who were enslaved at the time this law was passed would remain the property of their owners for life. Children born after 1793 would be slaves until the age of twenty-five and their children would be free at birth.7 There were two opposing, simultaneous effects of the Limitation Act. First, enslaved Africans, whose slave status was reinforced by this law, began fleeing Canada for northern American territories such as Michigan, and secondly, Canada became a haven for American slaves who wanted to secure their own freedom. Consequently, a wave of fugitives immigrated to Canada, the new symbol of freedom, especially following the passage of the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law.8

Forty years later, abolitionists world-wide claimed victory when the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 was made law, completely abolishing African slavery in all British colonies and granting freedom to almost one million enslaved Blacks in sixteen British colonies, most in the West Indies but also in South Africa and Britain. As of Friday, August 1, 1834, all enslaved children under six years old and any born after the effective date were free and no longer legally slaves. Celebrations and observances were held in all of the affected areas. For many though, this meant only partial liberation because all charges seven years old and over were to become apprentices of their former owners. Field labourers would have to serve a six-year term and all other former slaves would serve a four-year apprenticeship, after which they would obtain complete emancipation. Former slave masters were to be compensated for the loss of their free labourers from a £20 million fund, but none was allocated to Canadian slaveowners.9

Islands such as Bermuda, Trinidad, and Antigua did not implement apprenticeships and instead freed slaves from August 1, 1834. In fact, Trinidad became the first country to declare a national holiday to commemorate the ending of slavery. Although the Act did not mention Upper Canada, it immediately liberated approximately fifty Africans who remained enslaved, including young slaves like Hank and Sukey who were owned by a Mrs. Deborah O’Reilly of Halton County and still considered chattel property. In 1834, they requested and received their freedom.10 These colonies were the sites of inaugural Emancipation Day celebrations as newly liberated Africans rejoiced, parading through streets, attending church services, and engaging in other festive cultural activities.

Within four years, slaves in the colonies of Barbados, Bermuda, Guyana, Jamaica, and South Africa received their full freedom because the limited apprenticeship system of the Emancipation Act they adopted was brought to an early end. On August 1, 1838, these islands officially ended apprenticeships, granting total emancipation to approximately four hundred thousand indentured servants. This, of course, was an occasion for joyous celebration, because now complete abolition had been achieved in all British colonies. On August 1, 1838 in Spanish Town, then the capital of Jamaica, a hearse containing chains and shackles often used to restrain slaves was driven through the streets and then symbolically buried followed by bonfires and feasts. It was also noted that the soon-to-be ex-slaves climbed the hills and waited for the sun to rise, the dawn of the first day of freedom.11 Early Emancipation Day celebrations in the British Caribbean began to take place as part of Carnival and integrated numerous elements of other African-influenced cultural rituals such as jonkunnu in Jamaica and canboulay in Trinidad. These festivities involved the playing of musical instruments, singing and dancing, parading, theatrical acts/shows, and feasts. Over a century later, Caribana, a carnival festival in Toronto, would originate from these roots.

During the next twenty-seven years, Emancipation Day celebrations in the free northern American states, the West Indies, and Canada were used as a platform to petition for the end of American slavery. Participants hoped that the spirit and the momentum towards freedom would continue to spread to the southern United States to free almost ten million still in bondage. Finally, in 1865 the Emancipation Proclamation legislated the manumission of enslaved African Americans. The various slave laws and abolition legislation enacted between 1793 and 1865 heavily impacted the transcontinental and global freedom movements. Likewise, they influenced the tone and the goals of Emancipation Day celebrations in the 1800s. The hard-earned success of the abolition movement culminated in an upsurge of freedom festivals up and down the Atlantic shore and gave birth to a significant African-Canadian tradition. August 1, 1838, was a true Emancipation Day, one that would continue to be celebrated for years to come.