Freedom is the most precious of our treasures, and it will not be allowed to vanish so long as men survive who offered their lives for it.

— Paul Robeson, valedictory speech, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1919.

Amherstburg, along the Detroit River, and Malden are two towns in Essex County that were the sites of large Black communities. Both locales are adjacent and were part of Malden Township until Amherstburg separated from the township in 1851. The earliest African settlers in the area were the slaves owned by French colonists and British Loyalists, such as Colonel Matthew Elliot who owned sixty slaves in 1784 when he arrived in Fort Malden (now part of Amherstburg) to settle on his land grant of eight hundred hectares. Other early Black pioneers included Loyalists like James Fry and James Robertson, who settled on land grants in the area.1

The early nineteenth century witnessed an exploding fugitive population in Amherstburg, the most accessible town in Essex County for the fleeing slaves. Situated along the Canadian side of the Detroit River, it was located at the narrowest point that refugee slaves could use to cross the river from the American side. Not surprisingly, at that time Amherstburg was one of the principal terminals on the Underground Railroad. In the 1820s, Black fugitives living in Amherstburg introduced tobacco farming while others ran small businesses such as grocery stores, barbershops, hotels, taverns, and livery stables, or worked various occupations like mechanics and carriage drivers. By 1859 the Amherstburg’s Black community numbered about eight hundred while the neighbouring Malden Township’s total population was nine hundred.

Blacks embraced their new British citizenship and took measures to secure and exercise their freedoms and rights. African-Canadian troops protected Upper Canada at Fort Malden against American attack during the War of 1812 and the Mackenzie Rebellions in 1837 and 1838. American expansion into Canada, for them, would almost certainly mean a return to slavery.

The development of religious, cultural, and social institutions was central to the survival and success of local Black citizens. A British Methodist Episcopal (BME) church was established in Malden in 1839. The First Baptist congregation, formed around 1840, constructed a church on George Street in 1845–49, and the Nazrey American Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church was established in 1848. These churches also functioned as schools, which was equally important to the community as the local common schools2 had been segregated since the 1840s and the demand for education by children and adults was steadily increasing. With regards to Black and White children attending common schools, the prevailing sentiment in the Amherstburg area was that “Local trustees would cut their children’s heads off and throw them across the roadside ditch before they would let them go to school with niggers!”3 The school board built the King Street School for African-Canadian students in 1864. It remained segregated until 1912.

Amherstburg was an epicentre of anti-slavery activity carried out by both Blacks and Whites. The Black churches passed anti-slavery resolutions at annual conferences and even joined the Canadian Anti-Slavery Baptist Association, headquartered in Amherstburg. Captain Charles Stuart, a White abolitionist mentioned earlier, helped many of the almost two hundred escapees who arrived between 1817 and 1822 to settle on small plots of land while he lived in Amherstburg. He received a large land grant in the northeastern section of the town for this reason. Presbyterian minister Isaac Rice of the American Missionary Association (AMA) began working among the fugitives in Amherstburg in 1838, giving out clothes and food and running a mission-funded school. Levi Coffin, the Quaker often referred to as “president” of the Underground Railroad, visited Amherstburg in 1844.4 He stayed with Rice while he toured the province to see how fugitives, some of whom he assisted, were adjusting to a free life.

In 1854, members of the Black community in Amherstburg created the True Band Society to combat discrimination. The group encouraged self-help and community building through economic development and education, and provided financial support for refugees. They promoted unity among Black churches, as well as political involvement and integration throughout the dispersed settlement. The parent group of the fourteen chapters in Canada West, which consisted of six hundred members, later moved to Malden. As well, a number of fraternal organizations were based in Amherstburg in the middle of the nineteenth century. This included societies such as the Prince Hall Masonic Order and the Lincoln Lodge No. 8 F. & A.M., one of the oldest Black Masonic lodges in Canada.5 Although Blacks in Amherstburg experienced some degree of equality until the 1840s, the arrival of the Irish and other European immigrants resulted in some displacement of African Canadians and an increase in racial prejudice. These fraternal institutions and the Emancipation Day gatherings endeavoured to heighten awareness of these injustices and to eradicate them over time.

According to Dr. Daniel Pearson, a native of Amherstburg, the recognition of Emancipation Day in Amherstburg began in 1834.6 Given the long history of Africans in the region, it is indeed likely that observances of the abolition of slavery occurred from the inception of Abolition in the British Empire. It was customary, each first of August, for Amherstburg’s Black residents to march down to the docks to receive and welcome one thousand or more guests coming over the river from Detroit and from Windsor. People also came from nearby Colchester, Kingsville, and Sandwich, as well as from more distant areas of the province and the United States. With Sandwich, Windsor, and Malden a fairly short distance away, commemorations periodically alternated among these towns or were split between locations. For example, Malden was the selected location for the 1852 Emancipation Day celebrations in Essex County. In 1875, the day program was held at Walkers Grove near Windsor and in the evening a soiree was held at the Amherstburg Town Hall under the auspices of the local Black Order of Oddfellows. Then, in 1876, Emancipation Day activities occurred at Prince’s Grove in Sandwich.7

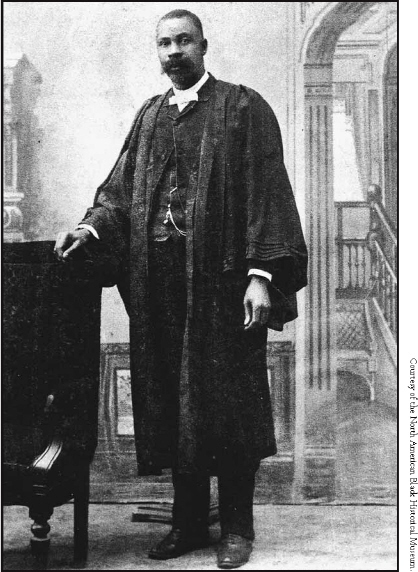

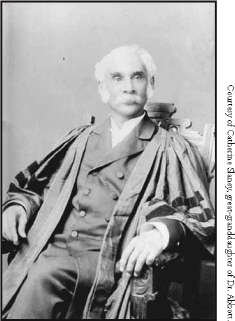

Delos Rogest Davis faced discrimination on his path to becoming a lawyer. Like all law students, he was required to article with a practising lawyer for a period of time before taking the entrance exams for admission to the Ontario bar, but for eleven years no White lawyer would hire Davis. He appealed to the Ontario Legislature in 1884 to ask the Supreme Court of Judicature to grant him admission to the Ontario bar providing he pass the exams and pay the required fee. His appeal was granted, and on May 19, 1885, Delos Davis was admitted to the Law Society of Upper Canada.

About two thousand individuals assembled in Amherstburg in 1877 to celebrate the abolition of slavery. The procession was accompanied by the Amherstburg Cornet Band and led by the mounted marshals Daniel “Doc” Pearson and Mr. J.O. Johnson to the docks to greet American guests arriving by steamer. The marchers continued through the town to Caldwell’s Grove8 to enjoy an outdoor lunch and hear uplifting speeches. A dance was held in the evening at the Sons of Temperance Hall on Ramsay Street in the old building of the newspaper, the Amherstburg Echo, located across from present-day Duby’s furniture store.

Caldwell’s Grove was the site for the forty-fifth anniversary of the Emancipation Act. In 1879 Daniel Pearson of Amherstburg was appointed the chairman. Over three thousand gatherers paraded through the principal streets of the town and then went to the grove for a picnic lunch, games, dancing, and the anticipated speeches. The first speaker was lawyer Delos Rogest Davis,9 the son of a former slave. He had grown up in Colchester about twenty kilometres south of Amherstburg. Davis stated that all present should be grateful to be able to assemble on free soil and supported his statement with a legal perspective, saying that any infringements of rights should be blamed on the perpetrator because the laws of Canada did not discriminate. He then went on to identify areas of existing racial discrimination that included denial of access to a good education, of the right to serve in the military, and the right to sit on juries. Davis encouraged African Canadians to demand equality and fair treatment. Other addresses were given by John Richards from Detroit; Mr. Lewis of Toledo, Ohio; and Michael Twomey, the mayor of Amherstburg. An evening program was held at the local BME church to raise money for the church, followed by a dance at the Sons of Temperance Hall.10

In 1889, several August First celebrations took place in Essex County, at Central Grove — close to Harrow, Sandwich, Windsor, Chatham, Detroit — and at Amherstburg. Once again, lawyer Delos Davis presided over the day’s event in Amherstburg. The recurring theme of the addresses delivered that day was the importance of education. Reverend Josephus O’Banyoun11 encouraged listeners to “educate their children,” Reverend J.S. Masterson of Windsor argued that “education … was the only way to be able to march on,”12 and Dr. James Brien, Member of Parliament, stated that “the earnest pursuit of education would enable them to take advantage of all opportunities for advancement both moral and material.”13 More messages came from Gore Atkin, a farmer and former warden of Essex County, who pointed out the benefits of knowledge in the abolition movement, because first “the English people were not then ready for it. The people had to be educated to a measure of this kind….”14 Reverend Mr. Williams from North Carolina, a child of formerly enslaved parents, said that Blacks “in his State, they had forty institutions of learning, yearly sending out 240 thoroughly educated pupils.” He further advised the crowd to “love morality education and religion and always look well to the future.”15 Reverend E. North of Colchester South pointed out “the power of education to remove prejudices against their race, as it elevated them in all relations of life and qualified them to fill any position in the land.”16 Lastly, the member of the provincial parliament, W.D. Balfour, remarked that African Canadians “were also being recognized in Government appointments in the country as well as at the seats of Government, and were educating themselves up to the requirements of these positions” and concluded the program “by urging them all to make great sacrifices, if necessary, to enable their children to take advantage of the many educational facilities now at their disposal.”17

Coincidentally, Emancipation Day was used to promote education when two years later in Chatham speeches were aimed at mobilizing community members to fight against segregated schools, which were still prevalent in some areas of Ontario, including Amherstburg. All Blacks knew that a quality education would afford African Canadians the opportunity for a good life and in turn could be used to dispel racist stereotypes and dismantle the prejudiced school system. Education was a matter close to the hearts of Blacks, largely because of their long history of being denied the right to learn. In spite of the tremendous obstacles, people of African descent persevered throughout the centuries of enslavement in the New World to acquire knowledge, a goal that has remained a constant in African culture. Emancipation Day was an effective instrument in furthering this cause.

The 1894 recognition of August First is immortalized in the famous image presented on the cover of this book. The mounted marshal Moses Brantford Jr., a native of Amherstburg, led the parade. The procession started at the Waterworks lot (now part of the Navy Yard Park) and marched along Dalhousie Street to Caldwell’s Grove. The nearly one thousand participants enjoyed an array of foods and the music of the Harrow Brass Band from Detroit who provided the music for the day. While the day was a festive occasion, it was also a sad time because Dr. Daniel Pearson had recently passed away. Thus, the commemoration was also used to honour the man who had played an integral role in the organization of local Emancipation Day celebrations and who had been a prominent community activist. The chairman, Delos Davis, noted “They would all miss the presence of the old man whose delight it was to take part in such proceedings and to begin with the singing the ‘Year of the Jubilee.’”18

The first speaker, John H. Alexander,19 also paid homage to Pearson, and spoke to the fact that the community elders such as Bishop Walter Hawkins and men of his stature were disappearing. This was of grave concern to Alexander and others because the past was becoming a distant memory for many, and the younger generation were forgetting the history of their ancestors. He further highlighted the progress that people of African descent had achieved in Amherstburg and in the province, such as serving jury duty, receiving appointments as returning officers and auditors, and becoming teachers and lawyers, all of which was accomplished as a result of education. Subsequent orators included a number of ministers,20 including a Reverend George Bell of Detroit, and a Thomas Harris. Chairman Davis and Harris talked about the significance of Amherstburg to the history of Blacks in Ontario. Davis said he “was pleased to see the crowd gathered so near the place where so many of the colored race had first stepped upon free ground,”21 while Harris stated that “Amherstburg was the spot where so many of their race had landed in making their escape from the United States, guided by the north star.”22

Annual Emancipation Day commemorations also included sports competitions and musical performances. The Jubilee Singers, led by the Reverend O’Banyoun from the local Nazrey AME church, performed regularly. In the evening, the annual ball was held at the Amherstburg Town Hall. In the 1920s and 1930s, fraternal lodges — like the Lincoln Masonic Lodge, the Damascus Commandery No. 4, and Steven’s Lodge of Oddfellows — played important roles in sponsoring Emancipation Day events. Members of these groups also sat on the Emancipation Day committee. Several local and visiting orders such as the Blue Lodges and the Knights Templar led the street parades with their bands and drill squads. As noted, speeches were delivered by political and religious leaders like the member of parliament Eccles. J. Gott for Essex South and the Reverend A.D. Burton of the local AME church.

The North American Black History Museum consists of various buildings. It includes the museum and cultural centre, the Nazrey AME Church, and the Taylor Log Cabin, once the home of George Taylor, an escaped slave.

By the 1930s August First celebrations were more relaxed and less formal. No speeches were given and there was no structured program. The day became a more social affair of getting reacquainted with old friends and extended family members. “With the passing of the years much of old-time formality and ceremony has passed from these emancipation celebrations and they have become big, colourful, informal picnics, attended by both colored and white people in large numbers.” “Emancipation Day in Amherstburg has come to be just a happy reunion, with lots to eat.”23 Family and friends barbecued, picnicked, participated in organized games like baseball, and gambled.24

Essentially, this more leisurely format of August First celebrations in Amherstburg carried through the next few decades. Citizens of the town who wished to celebrate on a grander scale attended the colossal events held in Windsor between 1931 and 1966. When the Windsor commemorations died down and the revitalization efforts by Edmund “Ted” Powell, Walter Perry’s successor as the organizer for Windsor’s Emancipation Day, in the 1970s were unsuccessful, the North American Black History Museum (NABHM)25 in Amherstburg carried on the tradition of marking August First with a community observance, beginning in 1983.

Emancipation Day celebrations in Essex County moved to Amherstburg’s Centennial Park for a four-day festival. Henry White of the NABHM took over the planning of the event with the blessings of Ted Powell. White planned to reintroduce Emancipation Day to Amherstburg with the recreation of the photographed 1894 parade, a move deemed fitting because of Amherstburg’s long African-Canadian history. The featured guest speaker for the occasion was Ovid Jackson, the Black mayor of Owen Sound. Since that time, the NABHM has organized annual events on a regular basis and has incorporated a variety of activities to appeal to a wide audience. The holiday weekend includes museum tours, presentations, and special displays, along with the usual family activities at a local park. In 1992, a yearly golf tournament was introduced.26 The celebrations have continued annually into the twenty-first century.

The first African pioneers in Sandwich (initially known as l’Assomption) were the slaves owned by French and English colonists. Antoine Descomptes Labadie, a French fur trader, held several slaves; a member of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada James “Jacques” Baby considered about thirty slaves as his personal property; and William Dummer Powell, chief justice of Upper Canada, possessed a number of slaves as well.27 Other Black settlers included Loyalists who were members of Butler’s Rangers. They obtained land grants in and around Sandwich, a community about twenty-four kilometres north of Amherstburg. The first major wave of fugitive American slaves to arrive in Upper Canada between 1817 and 1822 chose to settle in Essex County, including the village of Sandwich, now a suburb of the city of Windsor.

By the early 1850s there was a steady influx of escaped slaves coming into the area, many via the Underground Railroad. The village became the site of fugitive settlement and a mission called the Refugee Home Society established in 1851. Under the leadership of Henry and Mary Bibb, the settlement scheme sold land to incoming fugitives and provided support and schooling. The homes of most of the Blacks were found throughout the village, dispersed among the White residents. For the most part they were accepted by their neighbours, except when it came to education. The Sandwich common schools refused to admit African-Canadian children, so the Black community took it upon themselves to secure the future of their children by organizing private schools, such as the small private school Mary Bibb set up in her home to help educate the children of fugitives.

The annual recognition of the freeing of African slaves in British colonies was not always a large group demonstration. Abraham Rex and William Murdoch, both Black men in Sandwich, decided to celebrate the 1st of August at LeDuc’s Tavern in 1843, a place regularly visited by White soldiers from the Stone Barracks, a military base.28 What is interesting about this example is the association of African Canadians with other users of this public space. Some early tavern keepers in Ontario owned Black slaves, primarily women, who worked to keep up the business. In other instances, free Black women were hired as servants to work in bars. In some cases Blacks were denied service or were subject to restricted seating, and so at times the tavern also became as site of resistance when individuals of African descent challenged these unjust practices. Another intriguing aspect is that some well-known taverns in places such as Toronto, St. Catharines, and Chatham were owned by Black men.29

Earlier communal Emancipation Day celebrations in Sandwich took place at Park Farm between 1838 and 1856, located on what is now the city-owned Prince Road Park. This property was the estate of Colonel John Prince who had received support from the local Black inhabitants in his successful bid for a seat in the Legislative Council. Apparently they believed he ordered the execution of four American rebel supporters of William Lyon Mackenzie because they killed a man of African descent during the course of an attack in the Rebellion of 1837. Annual festivities ceased being held on his estate after Prince voiced racist beliefs over the steady stream of escapees from American slavery, which estranged his Black voters and contributed to his political defeat.30

By this time Sandwich had become a centre of fugitive-led abolition activity. Henry Bibb founded the Voice of the Fugitive, Canada’s first antislavery newspaper, in Sandwich in 1851. Bibb, like hundreds of other self-emancipated slaves, relocated to this area because of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Along with several community-building initiatives, he and his wife Mary were instrumental in organizing Emancipation Day observances in Sandwich. The celebration in 1851, held at the Stone Barracks, was attended by hundreds “parading up” from Amherstburg, “many of whom were dressed in the red jacket uniform, who marched into Sandwich after a band of military music looking as bold and courageous as John Bull himself.”31 Visitors from Detroit sailed across the Detroit River in the steamboat Alliance. Participants in the long parade included the Fugitives Union Society, whose anniversary and annual meeting was held that afternoon. The county’s high sheriff opened the assembly, followed by regional speakers including J.J. Fisher of Toronto, George Cary of Dawn, Samuel Ringgold Ward,32 and other American lecturers. The committee passed two motions, the first being to publish the days’ proceedings in the Voice of the Fugitive and the second to hold the next year’s event in Malden, but it was held in Windsor instead.33

Proceeds of the sales of admission tickets as well as the purchases of lunch, dinner, and refreshments went towards the construction of a brick building for the Baptist church on Crown-designated land located on West Peter Street. The building project for the Sandwich First Baptist Church, initially organized in 1840, was completed in 1851. Mary Bibb was one of the fundraising managers: “Dinner will be furnished by the Ladies for twenty-five cents per ticket. — Refreshments may be had during the day and supper in the evening. The proceeds will be appropriated towards erecting a Baptist church.”34

Sandwich Baptist Church was one of the community institutions that were created by fugitives. The church not only provided spiritual assurance, but physical security as well. Sandwich Baptist was a terminal on the Underground Railroad. There was a secret room beneath the church where escapees were hidden whenever the arrival of bounty hunters was announced by the ringing of a bell. Church parishioners kept lookout during services, as that was when bounty hunters liked to make surprise invasions. If alerted, fugitives escaped through a trap door in the floor of the church. Additionally, a tunnel running from the end of an underground passage connected the secret room to the nearby banks of the Detroit River.35

The August First commemorations also exposed the vast network of anti-slavery activists located across the continent. On his 1854 visit to Canada West, Levi Coffin, “president” of the Underground Railroad, attended Emancipation Day celebrations in the Maidstone area, which he described as, “a dense settlement of fugitives about eight miles south of Windsor.”36 He was part of a large group from Windsor, who, along with other guests, gathered at the schoolhouse run by Laura Haviland, a White Canadian-born Quaker, at the request of Henry Bibb and his Refugee Home Society in Sandwich. Invited speakers from Detroit delivered public addresses on a stage set up in a grove near the school. Coffin met and received many thanks from several freedom seekers he had assisted in their flight to Canada.37 In 1855, an estimated seven thousand people turned out at Prince’s Grove, the majority of them fugitives from American slavery, including thirteen who had been assisted to freedom by John Brown, a White revolutionary abolitionist from Kansas, and his son. Colonel Prince delivered remarks along with Eli Ford from Chicago. The evening galas were held in Windsor.38

However, by the 1890s, the direction and nature of Emancipation Day observances in Sandwich changed from a celebration of freedom, the maintenance of historic memories, and support of education to merriment and frivolity, so much so that leaders in the Black community, primarily church ministers, were calling for the event to be cancelled. What resulted were two different kinds of celebrations in the Windsor area, as described by the Windsor Evening Record in 1895. When celebrants from near and far arrived in Windsor, they split into two distinct groups: the first went to Walker’s Grove in Windsor and the second headed for Mineral Springs39 in Sandwich. The commemoration in Windsor was more serious in tone, focusing on spiritual and community prosperity through a steady schedule of lectures by notable local leaders such as Mayor Clarence Mason and Black alderman Robert Dunn. In contrast, the company in Sandwich did away with some of the traditional aspects of Emancipation Day in favour of having a good time by replacing them with lots of music, sporting activities, and barbecues.40

Colin McFarquhar, an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Waterloo, suggests that the separation occurred because slavery was in the remote past for too many of the attendees and few survivors were alive to tell the stories. Another reason he identifies is the decrease in speeches that recognized late freedom fighters and staunch abolitionists, resulting in the weakening of the collective memory that had been important in passing on shared historical experiences and cultural values.41

In the years immediately following, celebrations in Sandwich saw the introduction and growth of gambling, drinking, rowdy behaviour, and dance halls at Lagoon Park and surrounding venues. All of which became major problems, drawing complaints from both Black and White community leaders. In 1905, the mayor officially banned gambling and extra officers were hired to patrol the park grounds, instructing the police to arrest anyone who attempted to set up a game.42

Seven years later an association of Black church ministers appealed to the Sandwich town council to cancel the festivities, but they refused, perhaps because the stream of ten thousand people every summer brought an economic boom to the town. It is also interesting to note the change in tone of the media coverage of events. Previously, sermons and speeches were highlighted first at great length and the conduct of the crowd was always described as orderly. At the turn of the twentieth century the crap games, the arrests, and food were the main topics, with public addresses receiving little if any press, and the decorum that was highlighted favourably for the first sixty years of the celebration diminished greatly. Newspaper editors of the Windsor Evening Record joined in the chorus of unhappy Black voices calling for an end to the current trend of observances.

In 1913, the mayor of Sandwich, Edward Donnelly, announced that he would do his best to see that years’ celebration be the last because the event organizers refused to pay for the extra police officers that secured the event. His decision seems also to have been influenced by the pressure from the African-Canadian church ministers, coupled with the deterioration of the event.43

Interestingly, Mitchell Kachun, author of Festivals of Freedom, describes similar protests by African-American leaders about the change in objectives of the August First celebrations in the United States during the early 1900s. These leaders across North America wanted a separation of popular entertainment and commemorative events as the former threatened the spirit of Emancipation Day, and, by extension, the political movements in their respective communities. He argues that the shift was illustrative of a continental trend of increasing “commercialization of leisure,” urbanization, and the development of popular culture that was impacting all forms of early culture across Canada and the United States and not just freedom festivals.44 By 1915, Emancipation Day observances in Sandwich had ceased. Consequently, it appears as though the original meaning of August First as a commemoration of freedom, rights, and opportunities could not be reconciled with the emergence of mass entertainment.

By the 1830s and 1840s sizeable Black communities had developed in places such as Windsor, Sandwich, Amherstburg, and the surrounding vicinity. Hundreds of fugitives entered Canada by crossing the Detroit River, taking advantage of the more straightforward access point. Many came to Windsor because the town was a major terminus on the Underground Railroad, and along with Sandwich offered an initial safe haven for fugitive slaves. Dr. Daniel Hill identifies the first influx of refugees as arriving between 1817 and 1822.45

By the mid-nineteenth century, Windsor was emerging as a booming commercial and industrial centre. There were over fifty Black families living there by 1851 and seven to eight hundred individuals by 1868. Many of the Black men worked for the Great Western Railway in the construction of the rail lines and later as porters for the trains. Others were employed as labourers, barbers, coopers, draymen, preachers, and sailors. One man was working as an engineer, and another man, named Labalinin Harris, was a postman. Members of the town’s African-Canadian community owned an array of businesses including plastering, masonry, and carpentry companies, blacksmith shops, tailor shops, grocery and general merchandise stores, shoemaking shops, a confectionery shop, a paint and varnish store, and several farms. Black women were mainly employed as washerwomen and domestics, while a few were teachers.

Most Blacks in Windsor resided on McDougall, Assumption, Pitt, Pellisier, Church, and Goyeau Streets as well as on Bruce Avenue. With the Black population growing daily, several cultural institutions were established to aid in settlement, provide a sense of solidarity, challenge American slavery, and to help their members weather the increasing racism that punctuated their daily lives.

Although not welcomed in many White churches, Blacks in Windsor actually preferred to worship amongst themselves and several Black churches took root in Windsor. The British Methodist Episcopal Church was constructed on McDougall and Assumption Streets in 1863. The First Baptist Church used two buildings on McDougall Street near Albert in 1856 and 1862, and then in 1915 they relocated to a new location at Mercer and Tuscarora Streets. A Baptist Church formed the Amherst Regular Missionary and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, although in existence for decades, through worship in homes, erected a building at Mercer and Assumption in 1889.

To meet the educational needs of the community, mission schools or private schools were established to serve the children and the adults of the Black community, the African-Canadian children in Windsor having been barred from attending common schools. Before earning the distinction of becoming the first female editor of a newspaper in North America, Mary Ann Shadd was hired as a teacher in a private school for Black children in Windsor. Classes were held in the old military barracks in 1851 until a schoolhouse was built in 1852. A handful of White children also attended this school. When Shadd left in 1853, there were no separate common schools for the growing Black population until 1858 when the Board rented an old, run-down building to serve its purpose. In 1862, the St. George School was built for African-Canadian children at McDougall and Assumption Streets. By 1864, the school was accommodating 150 students.

Blacks in Windsor organized other self-help societies to further strengthen the community like the Temperance Society formed by Robert Ward and Henry Bibb, the Mutual Improvement Society established by Mary Bibb “to hear speeches and improve their minds,” and the African Enterprise Society led by William Jones.

Anti-slavery initiatives flourished in Windsor with its high concentration of fugitive supporters. Henry Bibb was appointed as the local vice-president of the Windsor branch for the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. Bibb’s newspaper, the Voice of the Fugitive, which began in Sandwich in 1851 and moved operations to Windsor shortly after, played an integral role in the Black community by providing information to local Blacks and attacking the enslavement of Africans in the southern United States. Bibb himself was a fugitive slave from Kentucky and was very active in the abolition movement through his paper and assistance in the settlement of recent escapees. He also managed the Refugee Home Society in Sandwich. White sympathizers active in the movement included John Hurst, who worked with fugitives in Amherstburg before being assigned to Windsor in 1863. As minister of the All Saints Anglican Church, he attempted to integrate his congregation.

Blacks in Windsor also organized themselves to protest and challenge the many forms of racism they faced on a daily basis. In 1855 they were denied the right to purchase town land lots. Blacks like Clayborn Harris and a Mr. Dunn launched legal challenges against the school board in 1859 and 1884 respectively. Mr. Harris complained that the property rented for the Black school was inadequate, but he lost his case. Mr. Dunn took the school board to court for denying admissions to his child. The superintendents’ defence was that it was unsanitary to admit Black children and the courts ruled in favour of the school board. People of African heritage who visited Windsor were refused hotel accommodations. They were not allowed to join Boy Scout troops or the local YMCA. On occasion there were incidents of physical attacks by Whites.

Blacks in Windsor also sought to secure their rights and freedoms through military service. About two hundred Black men defended the Detroit frontier against attacks from Americans during the Rebellion of 1837–38. Josiah Henson, one of the founders of the Dawn Settlement, commanded Black volunteer companies, part of the Essex Militia that commandeered a rebel ship attacking Sandwich. During the First World War, dozens of Windsor’s Black men enlisted in the all-Black No. 2 Construction Battalion in 1916, whose duties included logging, milling, and shipping.

Emancipation Day festivities, which have been held in Windsor since the 1830s, were a culmination of these social dynamics. Because the villages of Windsor and Sandwich were only three kilometres apart (Sandwich amalgamated with the City of Windsor in 1935) and Amherstburg about thirty kilometres away, at times the locale for these commemorations alternated among the three locations. These Ontario towns always received support from the African Americans living in nearby American states, which meant many additional participants. In 1852, large numbers of celebrants from Detroit (their city’s Emancipation Day event had been cancelled), attended the festivities in Windsor.

Because of proximity, Canada shared a close relationship to Detroit and in fact that city was a part of Upper Canada until 1796 when the British surrendered, transferring British administration to the Canadian side thirteen years after the end of the American Revolutionary War. For some time African Canadians had fostered strong social and economic ties to African Americans in Michigan cities like Detroit and Ypsilanti. People from both sides would attend each other’s social events and African Canadians often found employment across the border.

On this day in 1852, as every year, American residents took the ferry across the Detroit River. The street parade began at the military barracks, the present-day site of City Hall Square and Caesar’s Windsor. At the time, the barracks also served as temporary shelter for incoming fugitive slaves. Marchers went to meet the Detroit visitors including the Sons of Union, a Black lodge who arrived by ferry and joined the procession. The grand marshal and assistant marshal escorted them on horseback, and participants carried banners with the phrases, “God, Humanity, the Queen, and a Free Country” and “Am I not a man and a brother?” A Black militia from Amherstburg arrived and were “given the right of the line of march.”46 Another group participating in the parade was the Canadian Friends of the North American League who were identified by the badges they wore.47 The procession continued on to the Pear Tree Grove for a Thanksgiving church service where an anti-slavery song was sung, and Reverend W. Munroe from Detroit delivered an the sermon.

Participants then adjourned to the bank of Detroit River to hear the speeches of the day. Henry Bibb, as Emancipation Day president, extended a warm welcome to all visitors from near and far. Addresses given were directed to the hundreds of African-American freedom seekers in the audience and offered valuable advice on how to benefit from their new, free life. Reverend Munroe recommended that “colored people must work out their own elevation, not trusting the imaginary philanthropy of political rulers.”48 Reverend Samuel May from Syracuse, New York also presented “some noble suggestions to the colored refugee in Canada in relation to how they should get to elevate themselves in the scale of being.”49 The third speaker was Reverend Mr. Culver from Boston, Massachusetts (a White minister), who “urged upon them the necessity of becoming tillers of the soul.”50 Esquire Woodbridge from Sandwich “urged them to go on in well doing, and they would be respected.”51 This comment referred to the way in which the newcomers were understanding and following the laws of the land more, for which they should be commended. He encouraged the crowd to continue to be law-abiding citizens and not to expect special treatment, but equal treatment in all areas including in the enforcement of laws.

After a savoury lunch the assembly resumed and a young girl read a composition she had written and dedicated to Queen Victoria in honour of the occasion. The report in the Voice of the Fugitive makes special mention of the speech by the seven-year old that made the audience proud. The inclusion of this story in the newspaper highlights the involvement of children in early Emancipation Day programs and demonstrates the importance of African-Canadian children receiving an education, a recurring theme at these festivals of freedom.

At the end of the program, Reverend John Lyle from Sandwich closed with the pronouncement of ten toasts to parties in Essex County, the United States, and Britain who were involved in some form in the fight against slavery.52 Indeed, within a short period of time Blacks in Windsor, like their counterparts in other Canadian centres, proved themselves to be industrious and progressive. They succeeded in acquiring ownership of land, exercising voting rights, obtaining an education, and being elected to public office.53

Observances in recognition of the sixty-first anniversary of Emancipation Day were held simultaneously in both Windsor and Sandwich, the result of a growing divergence among attendees over the meaning of this special occasion. Events in Windsor continued to focus more on intellectual stimulation and community development while festivities in Sandwich centred more on partying and having a good time. When out-of-town celebrants arrived on August 1, 1895, in Windsor, they divided into two separate groups with one set going to Walker’s Grove in Windsor to listen to stimulating speeches by Mayor Clarence Mason and Black alderman Robert Dunn. The other group went to Mineral Springs (later Lagoon Park) in Sandwich.54

The ushering in of a new century also symbolized a change in the significance of Emancipation Day and the way in which this notable day was observed not only in Essex County, but in North America as well. Despite the changes, the new kind of celebration seemed to have appealed to many segments of the Black community and Whites, too, as it continued to draw large crowds. Huge celebrations in the first part of the 1900s were hosted at Lagoon Park in the Township of Sandwich, and were attended consistently by several thousand people from Windsor, all points in Ontario, and American states including New York, Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. In 1905, five thousand of the attendees were from the United States and in 1909 an estimated ten thousand people converged onto Lagoon Park, including legendary boxer Jack Johnson. 55 It seems to have become a regular practice that there would be two separate celebrations in Essex County, the one at Lagoon Park becoming the most popular: “Lagoon Park drew the larger crowd of the rival celebrations.”56 Many gatherers enjoyed the afternoon activities in Sandwich that consisted of speeches, sports, games, midway rides, and sideshows, then partied in Windsor in the evening. The annual balls included a cakewalk and displays of the latest dance moves including the grizzly bear, the turkey trot, the bunny hug, tangos, two steps, and waltzes.57

The Depression era and the war years experienced another marked shift in the event in Windsor, which by far held the grandest and most elaborate Emancipation Day celebrations in Canada for over three decades through the 1930s to 1966. At its zenith in the 1940s to 1950s, the Windsor festival attracted more than two hundred thousand people annually. The August First celebration in Windsor was once the largest outdoor cultural festival in North America, drawing a racially-mixed crowd and receiving ongoing support from like-minded people in the United States.

The ninety-seventh Emancipation Day anniversary celebration was held in 1931 with guests from Ontario and the United States under the auspices of the British-America Association of Colored Brothers (BAACB).55 Approximately twenty thousand visitors were in attendance. This celebration was particularly historic as it also marked the centenary of the Underground Railroad into Canada. Letters of acknowledgement were received from Prime Minister Robert Borden Bennett, Premier Mitch Hepburn, Toronto’s Mayor James Simpson, and Robert Moton of Tuskegee College in Alabama.59 Honoured guests included Ray Lewis, the track athlete from Hamilton. The growth and popularity of Windsor’s Emancipation Day celebrations during this time period can be attributed to Walter Perry,60 the festival’s organizer since 1931 when he launched “The Greatest Freedom Show on Earth.” For over thirty years, “Mr. Emancipation,” as Walter was kindly known, worked diligently to restore the importance of a sense of community and history to the annual event. He worked tirelessly to revamp the commemoration because he wanted to create a better image. Under Perry’s leadership, the festivities expanded to four days, keeping most of the traditional elements while incorporating some newer forms of entertainment.

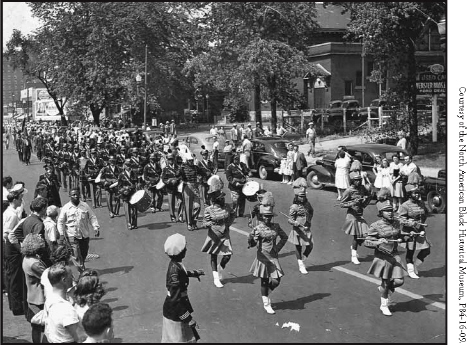

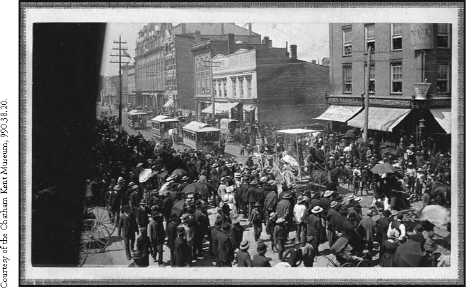

Event organizer, Walter “Mr. Emancipation” Perry, is the man in the white shirt who is shown walking along with the parade at the left of centre in the photograph.

Windsor’s yearly parade started from Riverside Drive at the edge of the Detroit River and marched north along Ouellette Avenue. The two-mile long procession, which ended at the Jackson Park grounds at Tecumseh Road West, required three hours to reach its destination. Crowds of Black and White people lined the parade route. Parade participants from Ontario and Michigan towns and cities included drill teams, marching bands, dignitaries, floats of Miss Sepia contestants, community businesses, and fraternal organizations. There was always a mix of entertainment at the park grounds such as fair rides, talent and beauty contests, sporting events, musical performances, speeches, and skill demonstrations that drew elite as well as up-and-coming athletes, singers, and community leaders. World-famous boxer Joe Louis fought in a friendly match. Jesse Owens, a 1936 Olympic gold medallist, demonstrated his track and field abilities. A young Diana Ross competed in a talent contest. Musical acts like the Temptations, the Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Sammy Davis Jr., and numerous gospel choirs performed over the years. Even actress Dorothy Dandridge attended on one occasion. Homegrown artists and groups also performed, such as the popular North Buxton Maple Leaf Band, formed by Ira Shadd in 1955, who participated in Emancipation Day parades in Windsor beginning in 1960.

Multiple spectators line the street to witness the Emancipation Day parade in Windsor. Parading past is the Union Company No.1, a Black Masonic Lodge from Detroit, Michigan.

Perry returned to the tradition of education and honouring the rich past of Africans in North America and the motherland through the mindful selection of speakers and the publication Progress. The magazine included articles about the history of Africans such as the Transatlantic Slave Trade, slavery, resistance, runaways to Canada, abolition, the achievements of Blacks in Windsor and North America, and the fight for equality and justice. It also contained advertisements for local businesses, both Black and White, and the program for Emancipation Day detailing the events and speakers at Jackson Park.

The goals and aims of the civil rights movement were intricately woven into Emancipation Day programming, to heighten awareness and challenge the policies and practices that denied African Canadians their full rights. One such infringement was the denial of the right of Black men to serve in the Canadian military during the Second World War. Other human rights infractions included the ongoing refusal of service in restaurants and bars, barriers to hotel accommodations and housing, and discrimination in employment and education. The BAACB also worked with other community groups in Essex County to address racism. They collectively received reinforcement from various levels in the region. Alvin McCurdy, president of the Amherstburg Community Club and active trade unionist, wrote to the federal government in 1943 expressing that African Canadians “want every single right and privilege to which our citizenship entitles us, no more, no less,”61 and, in 1947,Walter Perry appealed for “greater understanding of created racial problems.”62 Obviously, this formula was proving successful as the number of participants climbed steadily. In 1947, approximately fifteen thousand assembled at Jackson Park, while the 1948 event saw an astounding 275 thousand attend, and in 1949 about 120 thousand gathered.63

As part of the annual program, the BAACB presented awards to various citizens, politicians, and organizations; people such as Walter P. Reuther, the international president of the United Auto Workers– Congress of International Unions (UAW–CIO), and those individuals who had contributed to the betterment of the African race in some way. His brother, in an acceptance speech on Reuther’s behalf in 1950, declared, “While Jim Crow may have been kicked off the assembly line, he still lives smugly in many homes and many other places where humans gather.”64 One way the UAW–CIO had contributed to the civil rights movement in Windsor had taken place seven years prior when the union took a position against racial discrimination waged against a Black military officer who was refused service at a local restaurant. The union wrote a letter of support and distributed pamphlets to its members denouncing the racist action.

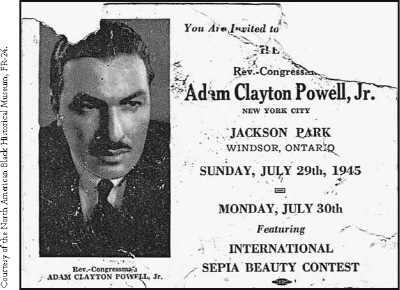

The 1950s witnessed the height of the American Civil Rights movement aimed at putting an end to Jim Crow laws legalizing the practice of discrimination against descendants of African slaves. But the battle for democracy and equal rights among Blacks and Whites was brewing in Canada as well. The BAACB invited civil rights activists from the United States throughout the mid-1940s to the 1960s, to motivate African Canadians to act against racism and to show how much they had achieved since the end of slavery. Numerous Black civil rights activists addressed Emancipation Day audiences in Windsor. American congressman and church minister Adam Clayton Powell was a guest speaker in 1945. Mary McLeod Bethune, an African-American female civil right activist,65 and Eleanor Roosevelt, President Franklin Roosevelt’s wife, spoke at Windsor’s Emancipation Day festivals in 1954. Twenty-seven-year-old Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attended in 1956 just after garnering international attention for leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott triggered by the arrest of Rosa Parks. The next decade saw speakers like Daisy Bates,66 an American civil rights activist; Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth,67 Baptist minister and civil rights activist in Birmingham, Alabama; and Mrs. Medgar “Myrlie” Evers,68 wife of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, deliver addresses to the throngs of people at Jackson Park. Emancipation Day had returned to its roots of being an effective political vehicle for the African-Canadian community.69

Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was the first African-American to be elected as a city councillor in New York City, in 1941. He was a special guest at Windsor’s Emancipation Day celebrations in 1945. A prominent civil-rights activist, he advocated for fair employment and housing for Blacks.

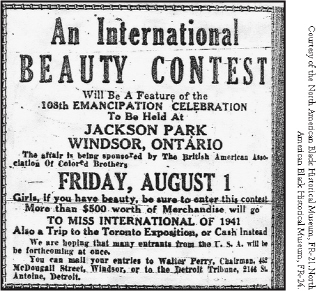

The Miss Sepia International Pageant was a unique feature added to the celebrations in Windsor. This beauty and talent competition, introduced in 1931, provided a platform for young African-Canadian women who otherwise would not receive such an opportunity. In the early twentieth century women of African descent were banned from entering mainstream pageants and women of colour were hardly ever featured in magazine or television advertisements. Contestants were judged on the basis of evening gowns, swimwear, and talent competitions. In addition to the honour of being crowned Miss Sepia, winners also received prizes in the form of cash, a trophy, and flowers. Local and American contestants took great pride in representing their cities and their race. Young girls also competed in the Little Miss Sepia Pageant.70 Other attractions at Windsor’s celebrations included the anticipated barbecue chicken, one of the most popular foods, and a variety of captivating forms of entertainment, such as an aviation stunt show.71

The 108th Emancipation Day program included the Miss Sepia Beauty Pageant, which was open to contestants from both Canada and the United States.

Preparation for this important annual social event on African-Canadian calendars required an extensive amount of work. Celebrations had to be planned months in advance to host hundreds and thousands of observers. Overnight accommodations needed to be available for the throngs of people staying in Windsor, and local restaurants had to be prepared to serve many visitors. According to one person’s recollections of the Big Picnic in St. Catharines, “All of the relatives came to stay. They would sleep anywhere — on the lawn, in a car in the driveway. The police would even put you up for a night until you found accommodation.”72 Cooking and baking had to begin days before the event. It is evident the yearly logistics worked out as Windsor’s celebrations remained successful for decades.

Janie Cooper-Wilson, born in Collingwood, Ontario, was crowned Miss Sepia in 1965 at the age of eighteen. During her teenage years she was a competitive baton twirler, her talent in the Miss Sepia International contest. She is the current Executive Director of the Silvershoe Historical Society.

Generally during these festivities, Black patrons were not mistreated or denied service because of their race. E.C. Cooper, president of the Chatham Literary Society, remarked that when he visited Windsor he ate “at a first-class restaurant amongst white gentlemen and ladies.”73 However, the same could not be said for attendees of events in Chatham. Throughout the end of the 1800s and early 1900s, African Canadians in Chatham and their guests were refused service in White establishments and could only frequent the few Black-owned businesses.

Three factors led to the end of Emancipation Day celebrations in Windsor in the middle of the twentieth century. Firstly, a fire at Jackson Park in 1957 caused extensive damage to the main event grounds just three weeks before the scheduled event. Secondly, the park was split into two by the construction of an overpass. Then, the 1967 race riots in Detroit led to the refusal of Windsor city council to issue the event permit because of security and safety concerns. No celebrations were hosted in Windsor for the years between 1967 and 1978, but eventually resumed in 1979 at a new location, Mic Mac Park. However, attendance fell dramatically. Shortly after, Windsor’s festivities merged with those in Amherstburg.

August First celebrations were revived in Windsor in 2008 by the Windsor Council of Elders and the Emancipation Planning Committee, with the support of several other community organizations and the City of Windsor, in honour of the 175th anniversary of the abolition of slavery throughout British colonies. The organization’s aim is to restore an awareness of family unity and identity to the African-Canadians in Windsor. The revitalized four-day event recaptured elements of the past by featuring foods from the African Diaspora, musical concerts highlighting hip hop, gospel, blues, and R&B artists, a sunrise church service and breakfast with a keynote speaker, a boxing demonstration, the Miss Sepia International Pageant, and a parade on Ouellette Avenue. The opening ceremony and reception on the Friday night was co-hosted by the United States Consulate General in Toronto, Mr. John R. Nay. Many provincial and American dignitaries, along with local dignitaries and community leaders were on hand to lend their support, such as Rosemary Sadlier, president of the Ontario Black History Society. New attractions to appeal to a younger audience included a three-on-three basketball tournament, a graffiti contest, and a tour of some local Underground Railroad historic sites. Many of the festivals events were held at the riverfront.74

An admission ticket to the Emancipation Day activities at Jackson Park in Windsor on August 5, 1962.

During the nineteenth century, Chatham was a developing commercial centre endowed with large export businesses and a series of smaller enterprises, many of which involved local African Canadians. African people have lived in Chatham as early as 1791. A Black man, possibly named Croucher, is recorded as a resident of the town that year. There were seven Black families in 1832, and the population surge as a result of the influx of runaway slaves saw almost two thousand by 1860, a figure that accounted for one-third of Chatham’s total population. Refugees were attracted to Chatham as the community with its large, welcoming Black community and ample employment opportunities had gained the distinction of being an ideal place for incoming African Americans. Chatham’s Black pioneer community, concentrated primarily on the east side of town, was composed of a mix of free persons, fugitive slaves, and an increasing number of Canadian-born individuals, all with a variety of occupational abilities. Some were skilled workers who operated their own businesses including shoemakers, carpenters, blacksmiths, bricklayers, masons, barbers, cigar makers, cooks, cabinetmakers, watchmakers, ship carpenters, and plasterers. Black labourers were able to find employment on farms, in mills, or lumberyards.

The Black citizenry established cultural institutions that were central to the African-Canadian community. By the 1850s Chatham had three Black churches with a combined membership of about 250 people. The First Baptist Church on King Street was erected in 1853. The Campbell Chapel AME Church, built in 1887 with bricks from Dresden’s British American Institute, was also on King Street. The Victoria Chapel became the mother church of the newly formed British Methodist Episcopal church in 1856, following the decision at the AME Conference of that year to split from the main AME body. In 1859, Victoria Chapel moved to Princess Street near Wellington Street with a congregation of about three hundred. These churches, along with several others, not only served religious functions, but social and political purposes, too. For instance, the last session of the John Brown Convention was held at the First Baptist Church on May 10, 1858.75 Many of these churches supported other anti-slavery campaigns. Schools, such as the Wilberforce Educational Institute constructed in the 1870s with the money raised by the solvency of the Dawn Settlement, were built to meet the needs of Black students who were prohibited from attending the public common schools. The office of the Black newspaper, the Provincial Freeman, relocated to Chatham in 1855 at the Charity Block at King and Adelaide Streets under the new ownership of the Shadds: Israel, Isaac, and Mary Ann. The publication, a valuable source of information about African-Canadian institutions in the province, promoted anti-slavery, integration, temperance, and literacy, reported on cases of discrimination, and discussed the concerns of the community.76

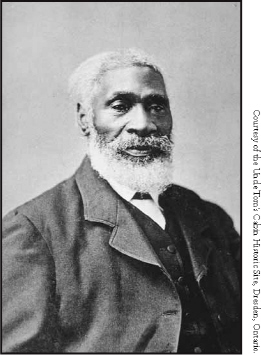

Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott, circa 1900, presented numerous lectures that addressed current issues in science, medicine, education, and social justice, even in his retirement. He was the coroner of Kent County from 1874 until he retired in 1881, at the age of forty-four.

Men of African descent in Chatham coordinated two voluntary militias of eighty men in 1838 to help provide defence during the Mackenzie Rebellion and to practise drills using the guns of the British regular units. They remained active until the corps was disbanded in 1843. Members of the community organized social groups and benevolent societies, such as the Provincial Union Association, the True Band Society, and the Victorian Reform Benevolent Society, to help refugees settle and to provide financial assistance to the sick, destitute, or for funerals. The several Masonic lodges and women’s auxiliaries, as well as a temperance group and the Chatham Literary and Debating Society, added to a network of social institutions addressing the demands of a growing fugitive population. As well as providing social support, these groups pushed for American abolition, assisted in the education and betterment of the community, and challenged anti-Black prejudice in Chatham.

Blacks in Chatham fought against slavery in many other ways. The large number of escapees, like Nelson Hackett,77 attracted bounty hunters to the area. In August of 1857, two White men from the United States came to Chatham in search of a runaway named Joe Alexander. They were confronted by a crowd of Black residents, including Alexander himself who ran them out of town. Chatham hosted the meeting of the Canadian Anti-Slavery Baptist Association in 1854 and an all-faith convention was held in December 1855 to discuss how local Blacks could be active in the abolition movement. Some local Black anti-slavery activists included members of the Shadd family, Osborne Anderson, Martin Delany, and Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott.78

They also battled racial discrimination in its usual forms. African-Canadian children were excluded from public schools in Chatham. In 1832 there was such strong opposition to their attendance from White parents that Black parents were forced to keep their children home. A segregated educational system lasted for about sixty years in Chatham and was even upheld by the courts until the practice was legally struck down in 1890.79 Even with this, it would still be a few years, until 1904, when integration began to occur. During this time Blacks in Chatham fought against separate schools through numerous petitions, the first one in 1851, followed by a court challenge in 1861.

Residents of African descent could not purchase cabin-class tickets for a Chatham steamer and Blacks from out of town were denied hotel accommodations in local hotels. When a local White politician let his views be known that he did not want Blacks to settle anywhere near Chatham, the African-Canadian community used the power of their vote to remove him from office. Politician Edwin Larwill had expressed his racist views publicly many times. His intolerant position was representative of positions held by some of Chatham Whites who were showing increasing hostility towards Blacks as the number of fugitives and the number of European immigrants coming to the town increased. Some felt that Blacks had too many rights.

Beginning in the 1830s, the annual Emancipation Day commemorations in Chatham were celebrated against this backdrop of overt discrimination. In 1841, Emancipation Day was observed on July 20th. Over one hundred people gathered at the hospital building on the military base, the grounds surrounding the present-day Chatham Armoury on William Street North, beside Tecumseh Park. From there, the parade followed a band through some of the main streets. The procession was succeeded by a dinner and speeches, with William Lampton as chairperson. One speaker was Lindsay Taylor of Chatham who provided a detailed account of the beginning of the slave trade in Africa and its effects on the families and communities on the continent. Celebrations in Chatham in 1842 began at sunrise at the local military parade grounds with twenty-one rounds of ammunition being fired from a cannon by Chatham’s Black militiamen. Along with civilian participants, one hundred Black soldiers marched through the town and prepared the meal for a military-sponsored dinner, speeches, and a dance. Josiah Jones, a local Black farmer and service member, gave one of the addresses. He expressed how wonderful it was to be able to gather and celebrate this victorious day and how much admiration Black settlers possessed for Britain for releasing its slaves. Jones announced that when the groundswell of abolition sentiments reached the enslaved African Americans in the southern states from Britain, they would all rise up and destroy the opponents of “liberty and humanity.” Entertainment for the evening included musical performances and a dance in the officer’s building.80

By the 1850s the size and scope of the August First festivals had grown dramatically. An editorial in the Chatham Planet described the order of events planned for August 1, 1856. Various associations, societies, and lodges were invited to join the parade that assembled on King Street in front of the Second Baptist Church. They marched to the Grand Truck Railway depot on Queen Street, led by musical bands, to welcome hundreds of guests coming from Elgin and other locales, then proceeded to march to McGregor’s Grove at the south end of present-day Tecumseh Park to enjoy an extravagant meal. Reverend Mr. William King81 and Mr. John Scoble of Dawn were two of the many renowned speakers. The evening activities included a bazaar in the town hall on King Street near Market Square, hosted by the Victorian Reform Society.82

August 1, 1860, was observed with reverence and seriousness by the almost five thousand in attendance. People came from Detroit, Windsor, and other nearby towns for the event organized by C.W. Prince and Reverend W.H. Jones.83 A church service was held with the sermon featuring Genesis 28:17, which stated: “And he was afraid, and said, How dreadful is this place! This is none other but the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.”84

However, the commemoration of Emancipation Day was not only about enjoyment or an acknowledgement of the past. By the late 1860s the themes of Emancipation Day began to shift from celebrating liberation from slavery to advocating for the full rights and privileges as British citizens to ensure a better life for their children. With the increased persistence of anti-Black attitudes throughout parts of the province, as well as other areas of the country with sizeable African-Canadian populations, the gathering of hundreds of Black Canadians in one place provided an opportunity to boost public awareness of their mistreatment.

Observances in 1871 started off with a kilometre-long parade, replete with music, banners, and decorations from the BME Church Victoria Chapel. The crowd marched down Wellington Street to William Street then to the train station to receive guests from Windsor and other centres. The train from the west had thirteen full coaches; others arrived by carriage and by steamer. Guests joined the procession and approximately four thousand people, including the many visitors from Detroit and other American cities, walked to McGregor’s Grove. Black parents, greatly concerned about what the future held for their children, often had their offspring participate in the parade, such as the thirty little girls dressed in white dresses with wreaths of flowers around their heads that were featured that year.

Isaac Holden85 shared the history of Blacks in Ontario since the 1850s wave of fugitives. After a two-hour dinner accompanied by music by the Jones’ Brass Band and a band from Detroit, the lineup of speakers continued. R.L. Holden, a lawyer from Cleveland, Ohio, and brother of Isaac Holden (R.L. later moved to Chatham) gave the next address characterizing the progress of Blacks in Canada as being behind the United States even though British territories obtained freedom first. He particularly noted the increase of racial prejudice in Ontario and in British Columbia.

Reverend William Hawkins, bishop of the BME in Canada West, who had spoken earlier to praise emancipation, addressed the listeners again. He reinforced R.L. Holden’s point, stating that at least Blacks in the United States helped to fight prejudice through the use of force. The next speaker, from Detroit, said that he, too, agreed with Holden because there were no more segregated schools for Blacks in Detroit, but this segregation still remained in Canada. The civil rights of African Canadians were not improving over time, but were being severely eroded, a trend that needed to be changed. Otherwise, what kind a life would the future hold for young African Canadians who had been born and raised here, for Canadian-born citizens, and for established immigrants?

When the meeting closed, participants reorganized the procession and escorted guests to the train station and the harbour. St. John’s Lodge No.9 held an evening program at the Drill Shed and the funds raised from ticket and food sales were donated to their widow and orphan charity. Just as in other city centres like London, Hamilton, and Toronto, fraternal orders in Chatham were very involved in Emancipation Day functions, an event that helped them build support for various causes benefiting the Black community.86

At times Emancipation Day was used to fulfill a more political agenda based on issues that Ontario’s African-Canadian citizens were experiencing at that particular time. In 1874 Chatham cancelled most of the traditional festive activities. Instead they held a political rally to protest the racial discrimination faced by Chatham Blacks and the twenty-year failure of the Conservative Party to meet the needs of its African-Canadian constituents. Over two thousand people marched in a street procession led by the Union Brass Band. The protest began at Princess and Wellington Streets and included a cavalcade of about 150 carriages and wagons carrying the chairperson Grandison Boyd — the Black businessman who owned Boyd’s Block a section of commercial real estate on King Street West — invited speakers, and Masonic lodge members along with their wives and daughters. Participants marched to Mr. Tobin’s farm for the day’s program. E.C. Cooper outlined how the ruling Reform Party had secured political and civil rights for Blacks in Chatham in the past three years.

The following speaker, J.M. Jones, criticized the Conservatives for attempting to gain Black votes by bribing them with a free boat trip to Detroit during election time and likened it to the ride given to Africans in the horrendous Middle Passage. Exercising the power of their vote would be critical to obtaining the full rights and privileges held by other Canadian citizens. He stressed that their votes should be strategically placed for the Reform Party. Jones then went on to discuss two similar but separate cases of racism. The first case was that of a daughter of a former militiaman of the 1837 Rebellion. In the second case, two men were denied soda water at a Chatham restaurant, and the men were subsequently charged with disorderly conduct. Although the counter clerk admitted that he refused service to the men because they were Black, the court case resulted in the male defendants being sentenced to keep the peace for one year. Jones also brought up another matter, which was the political scandal labelled the Elgin Association Fraud. In an apparent political ploy to attract Black votes, Reverend William King (former managing director of the Elgin Settlement) and incumbent provincial member Archibald McKellar were accused by the Conservatives of misusing settlement money for personal expenses. At the conclusion of the meeting a motion was passed: “Therefore resolved that we as electors of the counties of Kent and Bothwell, do exonerate the gentlemen above-named from all charges brought against them which we have found so basely untrue; charges made, in our opinion, to injure the colored people as well as those they were brought against; and hereby express our fullest confidence in them, and in the Government of Ontario, of which Mr. McKellar is a member; and pledge to them our united support, so long as they pursue the course they have done in the past.”87

After a picnic lunch, MP Archibald McKellar was the next person to address the audience. McKellar, like King, had a long relationship with the Black community in Kent County. An attorney, he was one of two White men in Chatham to support William King’s settlement project. Blacks in Kent County helped to vote him back in during the 1856 election, which he won over Edwin Larwill. (Larwill had beaten McKellar in the 1854 election.) The efforts of local activists such as Martin Delany to mobilize Black voters in support of McKellar resulted in almost three hundred African-Canadian votes, enough to create the winning margin. In his speech, MP McKellar outlined how he and his political party, the Clear Grits (Reform Party), treated Blacks fairly by pointing out that they had appointed Isaac Holden as councillor, designated Dr. Anderson Abbott as county coroner, and selected some Black men, like Charles Watt of Raleigh Township, as justices of the peace. African Canadians, as part of their British citizenship and rights as property owners, took advantage of their right to vote, a privilege at that time denied to the majority of African Americans. They understood the importance and the impact of voting and used their votes to remove racist politicians like Colonel John Prince and Edwin Larwill. They also utilized their votes to defeat politicians who did nothing for Blacks in parliament such as challenging the Common Schools Act. All of the Black voters in Kent County were able to sign their names in the voting register, but many of their White counterparts could only “make their mark.”

The next speaker was George William Ross, the MP for West Middlesex. He emphasized how Emancipation Day and reform were closely linked: those who agitated for liberation were themselves reformers of their day and Reformers now worked to free people from failed governance.88

When no commemorations were held in 1877, an editorial was written in the Tri-Weekly Planet on August 2nd, asserting that Blacks had become ungrateful and indifferent towards Britain who freed them. E.C. Cooper, president of the Chatham Literary and Debating Society, wrote a letter to the editor criticizing the opinion piece. He strongly disagreed with the editorial, pointing out that the land that was described as “free and just” refused to pay the former slaves (who were now labourers) the full value of their work and then left them to fend for themselves after being forced to work without pay. Cooper argued Emancipation Day should not be celebrated by Blacks any more than by the Irish. He asked whether the Irish were ungrateful, too because they didn’t recognize the Irish Emancipation Act of 1829. Cooper then suggested that the Irish be forced to celebrate for generations. Why didn’t the Planet tell Irish settlers they owe their liberty to Britain?

The absence of the annual celebration of freedom reveals the extent of discrimination against Blacks in Chatham and in varying levels of society across Canada. Because of their colour, Cooper argued, they could only stay in one hotel in Chatham, the Garner House, but in Windsor and across the border in Detroit Blacks could frequent any first-class hotel or restaurant without prejudice. Cooper pointed out that if one thousand Black visitors came for an Emancipation Day celebration tomorrow they would face blatant discrimination because there would be only one place they could go get a soda or an ice-cream cone. He asserted these were the reasons why Blacks in Chatham did not celebrate Emancipation Day. The sentiment among local Black residents was that limited rights for African Canadians should not be celebrated and that perhaps this move would force Whites in Ontario to acknowledge and end their racist practices.89

Consequently, the 1870s saw growing opposition to Emancipation Day celebrations in Chatham. Why celebrate freedom when basic rights and privileges were being denied? Anderson Ruffin Abbott echoed similar sentiments in an editorial piece he wrote for the Missionary Messenger in 1873, while living and working in Chatham. The change in opinion towards August First during this decade appears to exemplify the tumultuous state of civil rights and race relations in Ontario and the fact that Blacks seemed quite discouraged by their worsening social conditions.

Several identified factors were contributing to this situation. First, the Black population began to diminish, with hundreds of African Americans who had been living in Ontario now returning to the United States after the abolition of American slavery in 1865, a shift that affected the dynamics of the Black community. Simultaneously, there was a surge in European immigrants arriving in the area that led to a decline in opportunities for Blacks. White involvement in issues relating to the rights of Blacks steadily lessened. Further, when some Whites realized that a segment of the fugitive population planned on permanent settlement, anti-Black attitudes and White opposition swelled because of the imminent threat of close social interaction and intermarriage.

Interestingly, Emancipation Day commemorations in Chatham did resume shortly afterwards, as in 1882 a large number of people were described as gathering together for August First despite the stormy weather conditions in the morning. Celebrants, comprised of numerous lodge and cultural association members as well as people of the general public, travelled by train from other Ontario towns and many American states. In the afternoon, Isaac Holden gave a moving speech following the procession. He stressed the importance of recognizing those who actively fought for the freedom of Africans enslaved in British colonies and touched on the falling of the horrific institution of slavery in the United States seventeen years before. In closing, he reminded listeners to take advantages of the opportunities to improve themselves and strengthen their communities, to show themselves worthy of the rights and privileges granted to them in British North America. Later, the mayor, town council members, and Black and White gatherers attended a picnic in Tecumseh Park.90

However, those unresolved social inequality issues from several decades before resurfaced at Emancipation Day observances during the remainder of the century, such as the one held in 1891. The gathering at Tecumseh Park did not follow the regular program of church service, parade, and merriment in a relaxed atmosphere. James C. Richards, the chairperson of the day (he later became a BME minister) and leader of the new Kent County Civil Rights League (KCCRL), instructed speakers not to give the usual thanks and praises, but to speak about the goals of the League and why it was formed. After the hundreds in attendance, both Black and White, enjoyed a social luncheon at the Drill Shed and listened to music played by a band from Dover (just west of Chatham), the speeches began. This time the focus was on educating listeners on the organization’s aims and encouraging the community to address several grievances.

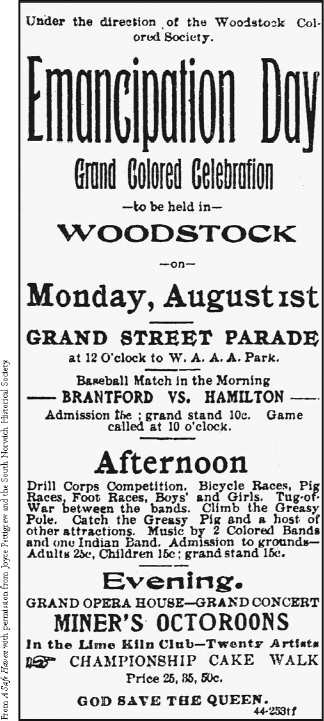

An Emancipation Day street procession at King and Fifth Streets in Chatham in August of 1885.

The lineup of speakers for the day was announced by the chair. Racial discrimination was the topic addressed — African Canadians in Chatham were not being allowed to exercise their full democratic rights. The Civic Rights League stemmed from the Chatham Literary Association, which had been formed to improve the lives and conditions of local Blacks. The main goal of the KCCRL was to unify Chatham Blacks in seeking redress for the many injustices they experienced: the lack of public schooling for African-Canadian children; Black men being barred from serving on a jury, especially in the trial of another Black person; and the denial of hotel accommodations and service at local food establishments. One argument presented was that if Blacks were accepted at bars, which were public places, they should be allowed to frequent all public places. The League sought removal of these barriers, to be followed by access to full citizenship rights. The first objective on the agenda was to launch a campaign against segregated schools. The monies raised from this Emancipation Day were to help pay for the initiative.

The underlying question was why did Whites view Blacks differently, even though they had demonstrated themselves to be just like any other Canadians? R.L. Holden argued sarcastically that there was no distinction when viewing Blacks as criminals. Reverend Josephus O’Banyoun, in sharing a personal example, commented on how he was ostracized at school in Brantford where he was born and raised, and on how he was singled out because of his racial background. Holden and Garrison Shadd reiterated the fact that Black citizens were just as loyal as White citizens were, “just as patriotic, just as willing to die for his country, as a white man and his citizenship should be as fully recognized.”91 As O’Banyoun stated, African Canadians only wanted fair treatment, not favours.