Black men and Black men alone, hold the key to the gateway leading to their freedom.

— Marcus Garvey, The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, 1923.

Brant’s Ford, now Brantford, Ontario, was home to a diverse group of Blacks since the late eighteenth century. They included slaves such as Sophia Pooley1 and at least two other male African captives of the over thirty mixed slaves owned by the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant (Thayendinaga) in the 1790s and the two Black slaves owned by John Thomas, a local merchant, as late as 1809, some fifteen years after the passage of lieutenant-governor John Graves Simcoe’s Act to Limit Slavery.

A number of fugitive Blacks were seen in Brantford in the 1830s, some having arrived as hidden cargo in boats, just like their counterparts in Oakville and Collingwood. In 1830, a Black landowner named John Boylston was listed as a blacksmith. Three more African families bought land in 1832: Adam Akin, a labourer who lived on Darling Street; James Anderson, also a blacksmith, who bought property on Dalhousie Street; and Samuel Wright, a barber residing on Colborne Street. By 1846 fifteen Black families had settled in or near Brantford. The town was a growing milling centre, providing adequate employment opportunities.

The families quickly established institutions to meet the needs of the growing community and to provide fellowship and support. The AME church opened in the mid-1830s and the BME Church, now called the Samuel R. Memorial Church, was formed first on Dalhousie Street then moved to Murray Street. Private schools were also established, as local common schools did not admit African-Canadian students. One Black school, opened in 1837, was said to have higher educational standards than the all-White school, which enticed some White parents to register their children there.2 However, not only were the residents of African descent not welcome in the common schools, it was also made known that they were not wanted in the town. Some White settlers petitioned the provincial government to have Blacks relocated north to Queen’s Bush, where a sizeable number of Blacks were clearing land for settlement.

As noted earlier, Reverend Josephus O’Banyoun, who was born and raised in Brantford, mentioned some of the racism he experienced in a speech delivered at Emancipation Day in Chatham in 1891. He described how he was ostracized at school in Brantford and harassed because of his race. George Sunter, another Black Brantford resident, wrote a letter to the Brantford Expositor to express his disdain for the prejudiced sentiments towards fugitives displayed by some Whites in the town and in the province.3

Reverend Josephus O’Banyoun was very active in Black communities across Ontario. His calling as a church minister and role as musical director for the O’Banyoun Jubilee Singers caused him to live in numerous centres in the province and to travel extensively around Ontario, in Canada, and internationally. His recurring participation in Emancipation Day commemorations in Ontario shows his involvement in addressing issues of concern to African-Canadians.

Brantford’s Black community gained public attention with the John Anderson case. A runaway accused of killing his master as he made his escape from slavery in Maryland initially made his way to Toronto and then to the Brantford area. He was the subject of a famous extradition case tried at Osgoode Hall in 1860. Anderson was freed after an appeal.4 This precedent-setting case is an example of how extradition to the United States and Southern slavery was challenged in Canadian courts.

Although Brantford’s Black population had decreased by 1860, there was still a sufficient number to publicly recognize Emancipation Day each year, with the event always receiving support from African Canadians from surrounding centres. The earliest known recorded account reported that a crowd gathered for a picnic on August 1, 1856, at a grove on the site of the Mohawk Institute on the Six Nations Reserve (the present-day location of the Woodland Cultural Centre). Both Blacks and Whites attended the evening reception that followed. Peter O’Banyoun,5 the father of Josephus O’Banyoun, presided over the program of addresses that praised the British Crown and condemned slavery.6

Likewise, people from Brantford went to Emancipation Day celebrations in other nearby towns, as was the case in 1859 when a contingent travelled to Hamilton for the elaborate jubilee at the Auchmar Estates in recognition of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the passage of the British Emancipation Act. Again, in 1886, a group of about fifty people went from Brantford by train to attend the commemoration in Hamilton. The men, some of them members of the Coloured Citizen’s band dressed in “black frock coats, light pants, white vests, and black plug hats,”7 and marched together to the celebration site to participate in games, play baseball, and have dinner.

Heather Ibbotson, local historian and journalist for the Brantford Expositor, stated that Emancipation Day “events were held in different locations and boasted a variety of entertainment over the years.”8 When some locals stayed in town in 1859 and observed the freedom holiday, they enjoyed a picnic and speeches at Strawberry Hill in west Brantford. An evening ball took place at the town hall at Market and Colborne Streets. In 1865, visitors from Simcoe were part of the celebration that consisted of a dinner at the town hall and a soiree in the evening. A dance was held at the Day Hotel on Vinegar Hill, now Clarence Street on the eastern edge of Brantford, for the 1871 observance. On August 1, 1875, the festivities commenced with a procession through the main streets of the town proceeded by a picnic at the Fair Grounds, now Cockshutt Park at Ballantyne and Sherwood drives. Entertainment at the yearly events included music provided by local residents of the Coloured Citizen’s Band, formed in 1880, and the O’Banyoun Jubilee Singer from the BME church. This popular choral group performed at many of the annual events including those in other towns like Amher-stburg, Hamilton, and Guelph. Members included J. Lucas,9 Thomas Snowden (no relation to Charles Snowden), Sarah Galley, and Beluah Curtis. In 1875, The Grand River Band, composed of local Native men, entertained the gatherers. Visiting bands from other major centres like Buffalo and Toronto also played at these events. Other forms of amusement included canoe rides, baseball games, and a myriad of contests.10

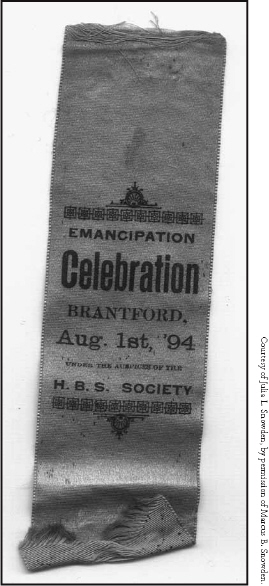

A souvenir ribbon from the Emancipation Day celebration held in Brantford in 1894, from the private papers and personal belongings of Charles W.F. Snowden (1868–1964) of Brantford, Ontario, inherited by his daughter Julia L. Snowden.

Emancipation Day in Brantford continued into the early twentieth century. By this time the event was organized and attended by many first- and second-generation African Canadians from the region. In 1894, a number of Woodstock’s Black citizens came to Brantford to celebrate. One of them, Solomon Lucas, a church minister and a member of the large Lucas clan living in Brantford, came to participate in the festivities and would have taken this time to visit his family. That same year, Jonathan “John” Tanner and his dance partner Miss Marshall won the cakewalk contest. Tanner was one of the founders of the Coloured Citizen’s Band. That year people joined together for an afternoon parade from Market Square through the core of the town to the Agriculture Park (present-day Cockshutt Park) to participate in sports, games, and dancing. The evening program moved to Wycliffe Hall located on Colborne Street by the Market Square for a musical concert with performances by the Reed Coloured Band from Buffalo, musical solos, drama, and drum and baton skill demonstrations. Afterwards, the several hundred celebrants assembled at Brantford’s town hall for the cakewalk followed by a dance, musical performances, and a night of dancing. Whites continued to recognize the end of slavery with their Black neighbours. Some who were present that day — Ab Grant, Mr. Stoleman, William G. Kilmaster, and Alderman Charles Whitney — were nominated by the crowd to judge the cakewalk.11

In 1903, an estimated one thousand guests from Toronto, Hamilton, Woodstock, Guelph, and other surrounding towns flocked to Brantford for Emancipation Day. After a street procession, all parties descended on Mohawk Park located on Lynwood by Mohawk Lake, where they spent the afternoon engaged in sport activities, boating on the lake, picnicking, and dancing in the pavilion. A baseball game was played between the Brantford team and a visitor’s team with players from Toronto and Hamilton. A lively ball took place that evening at the Drill Hall at Alexandra Park on Colborne Street with a cakewalk and character dances featuring costumes that “added greatly to the entire effect.”12

The organizing committee of the 1912 anniversary of the Emancipation Act was comprised of John McCurtis, Jasper Smith, Jesse Brown, Jerry Okley, and Charles Snowden,13 most of whom were descendants of fugitives that had settled in Brantford. Their plans accommodated the over seven hundred guests at Agriculture Park and included the usual activities. That year the baseball game was played between African-Canadian professional teams from Brantford and London,14 which the London team won. Music for the event was provided by the 37th Haldimand Rifles Band, primarily made up of Six Nations volunteer militiamen. The night closed out with an evening concert at the Armouries on Brant Avenue, followed by a dance. This occasion appears to be one of the last Emancipation Day commemorations in Brantford, where, in spite of social inequalities, an interracial group with citizens of African, European, and Native background were able to come together to celebrate the idea of freedom.15

Hamilton’s extensive Black history and sizeable Black population made it another key location for Emancipation Day commemorations. Black settlement in this large urban centre began with the slaves of Loyalists, followed by men of African descent who had fought for the British during the American Revolution and received land grants in British North America as compensation. From the 1820s through to the 1850s, dozens of African-American fugitives immigrated to Hamilton using the Underground Railroad. By 1861 there were 476 persons listed as “Coloured” or “Mulatto” in the Hamilton census.16 There were two main areas of Black settlement in Hamilton — “Little Africa” on Hamilton Mountain bordered by Upper Wentworth Street, Concession Street, Sherman Avenue, and Fennell Avenue, and the other along Main Street from Dundurn Castle to Wentworth Street North on the north side.

Residents of these areas were employed as cabmen, cooks, waiters, teachers, washerwomen, domestic servants, and teachers. Others were flourishing business owners of inns, grocery stores, tobacco shops, restaurants, fruit stands, barbershops, and even an ice company. Many of these new colonists enrolled in local Black military units to defend provincial and British interests during the Mackenzie Rebellion. They volunteered their service in the coloured company of the Fifth Gore Militia to ensure the security of their new lives on free soil. Black men from Hamilton, like former slave Nelson Steven17, also contributed to the fight to abolish slavery in the United States by going south to fight for the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Although Hamilton’s Black men demonstrated their loyalty to the British Crown and proved themselves to be hard-working, industrious citizens, they and their families experienced racial discrimination in various spheres of public life. As in many other locations, African-Canadian children either could not attend the same common schools as White children or were limited to restricted seating in schools in Hamilton. Black parents, many of them fugitives, petitioned Governor General Lord Elgin for admission to segregated public schools. Although officially they were integrated in the 1840s, Blacks developed their own separate schools, which were also attended by adults who had been denied an education as enslaved children. Schools like the Christian school on Concession Street in “Little Africa” sprang up because of continued prejudice throughout the 1850s. The level of persistent discrimination caused the Honourable Isaac Buchanan, MPP for Canada West and champion of the Black community, to express his views on the matter: “I think we see the effects of slavery here very plainly. The children of the colored people go to the public schools but a great many of the white parents object to it, though their children do not that I know of.”18

Black settlers in Hamilton also engaged in other anti-racism struggles. The Hamilton Black Abolitionist Society advocated for the end of African-American slavery and tackled particularly blatant forms of racial discrimination in the village of Hamilton, such as the time when Blacks were excluded from marching in “the parade that marked the laying of the cornerstone for the Crystal Palace.”19 Their protest, which also gained support from White residents, was victorious and citizens of African-Canadian ancestry participated in another major civic parade the following year. When Jesse Happy, a fugitive from Kentucky, escaped to Hamilton in 1837, a vocal Black community leader Paola Brown, the city bellman and town crier, successfully organized citizens to protest his arrest and imprisonment.20 Brown was also selected to speak on behalf of the Black community against segregated schools.21

In an effort to meet the social, economic, and political needs of the community and to create a united front against anti-Black prejudice, African Canadians formed solid cultural institutions including voluntary associations, schools, and churches. An African Methodist Episcopal Church, St. Paul’s, was established in 1835 on Cathart Street, then moved to Rebecca Street in 1856. The Coloured Baptist Church was organized in 1847 on McNab Street, and a British Methodist Episcopal Church was formed in the 1850s. Members of these sizeable congregations and other African-Canadian residents participated in the annual tradition of celebrating Emancipation Day, an event that also served their social and community development purposes. These August First observances extended their social network with support coming from African Canadians of the surrounding vicinity including Ancaster, Otterville, Toronto, Niagara, and Brantford.

In 1846, a musical band led an Emancipation Day parade through the main streets of Hamilton to the Anglican Christ’s Church Cathedral where Reverend Mr. John Gamble Geddes, a supporter of Hamilton’s Blacks, delivered a sermon, followed by dinner at city hall. The 1853 commemoration began with a street procession of about one thousand people where flags and emblems of various fraternal orders were displayed by marchers dressed in different uniforms. Gatherers sat together to share in a communal dinner at the Mechanics’ Institute Hall and to hear speeches. A party in the evening concluded the day.

In 1857, a marshal led the August First parade on horseback. Participants marched down to the wharf to welcome visitors from Toronto, who upon their arrival “gave three cheers for the Queen, three cheers for the captain and officers of the boat, and three cheers for British emancipation.”22 The entire party continued on to Christ’s Church for a service given by Reverend Geddes who preached about the similarities between the jubilation of the Jews when they were set free from Egypt and the day’s affair, which celebrated the release of people of African descent from bondage. The celebrants then joined together at the Mechanics’ Hall for a meal and for speeches that touched on the grace of freedom, the rights they now held like other human beings, and their appreciation to Britain for liberating African slaves in their territories.

For a number of years during the 1850s, the MPP for Canada West, the Honourable Isaac Buchanan, lent the grounds of his Clairmont Park estate as a host site for the Emancipation Day celebrations. Buchanan was a Scottish immigrant and successful businessman who gave of his money and time in support of various local causes, including initiatives that promoted rights and opportunities for Hamilton’s Black constituents. Buchanan and his family were described as, “big hearted folk [who] honoured the liberties of their fellowmen whether they were black or white.”23 Clairmont Park was an eighty-six acre (thirty-five hectare) estate that included a large, beautiful house named “Auchmar.” It was situated on Hamilton Mountain, the part of the Niagara Escarpment that that surrounds the city of Hamilton to the south and is locally referred to as the “Mountain.”

On one such occasion on August 2, 1859, over five hundred guests from the general public arrived at Auchmar at 1:30 p.m. after participating in a parade through the main streets and listening to Reverend Geddes’s sermon at the Christ’s Church Cathedral. The well-dressed guests, Black and White, were seated at tables covered by white linen and placed under the shade of apple trees. The sumptuous dinner, compliments of Mr. Buchanan, was comprised of, “roast beef, fowls, pies, pastry, oranges, fruits, nuts, and barrels of lemonade.”24 Afterwards, Buchanan addressed his company on the front lawn speaking about his hope for the extension and influence of British emancipation on the world. Other White community leaders such as John Scoble from Dawn addressed the visitors. Speakers of African descent included a Mr. Atkinson who articulated the history and atrocities of enslavement.

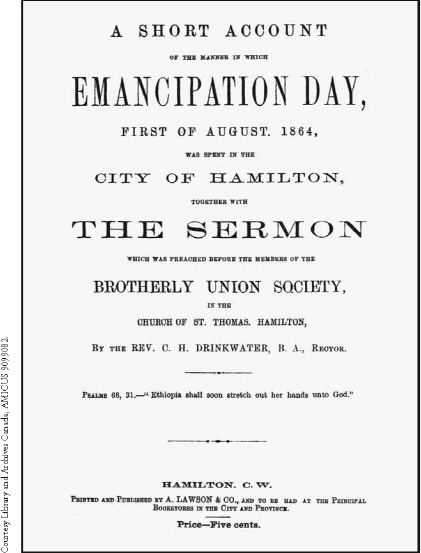

The 1864 celebrations began on McNab Street with a street procession formed by sixty men. They were led by the Storror’s Brass Band and marched along Main Street, down Wellington, then onto St. Thomas Church where Reverend Charles Henry Drinkwater delivered a sermon. He preached from Galatians 5:1, the verse that says, “Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be hot entangled again with the yoke of bondage.” The theme of his message was that redemption is at the centre of deliverance because “Christ has made us free.” He then went on to discuss the literal and figurative meanings of this Biblical text, the former referring to spiritual slavery through the captivity of sin. The latter and secondary meaning of this scripture, which was most relevant to the day, pertained to the yoke of slavery and the sufferings, which the enslaved had to endure. When they were deprived of all the rights of humanity, their deliverance came from the promised saviour who freed them from the bondage of corruption and admitted them into the glorious liberty of the children of God. Such sermons were deeply meaningful to their African-Canadian audience as they tapped into and reinforced the religious beliefs held by Blacks, and solidified the conviction that they were chosen by God and emphasized the role God played in the freeing of Black slaves.

Early Emancipation Day commemorations had strong religious characteristics. The day began with church services giving thanks for the blessings of liberation. This is the cover of the published sermon delivered by Reverend Charles H. Drinkwater in 1864.

After that, the reverend highlighted some of the benefits of emancipation such as Black men in Jamaica and other islands becoming planters and owning land, and pointed out that Africans were living productive, independent lives all across British possessions. Drinkwater then spoke on the pending end of slavery in the United States stating that “man shall enslave his brother no longer” and “Christ is the Great Emancipator.” He criticized people, including ministries, who wrongly used the word of God to justify slavery, and compared the deliverance from African physical slavery to deliverance from sin with Jesus’ crucifixion. In closing, his advice was not to be a slave to sin, to do well, to silence ignorant critiques of emancipation, and to “First, be Christians, educate yourselves and your children succour and exhort the weaker brethren.”25 After the service the parade re-formed and advanced to the decorated Albion Hall in Miller’s Block on McNab Street for a savoury dinner.

Approximately three hundred people, some from Toronto and London, assembled to partake in the meal and to listen to more speeches. Dr. Jenkins was the chair for the evening and he offered several toasts, first a salute to Queen Victoria, then a cheer for John Bull, and more. He encouraged Blacks to make use of the time to influence public opinion and to convince the world they were ready to fight and die for freedom. Reverend Thomas Kinnaird from Toronto gave the next address. He toasted Lord Lyons, the mayor of Hamilton, and Isaac Buchanan. Alexander Somerville, a White Hamilton resident and founder of the Canadian Illustrated News, spoke next providing a brief history of abolition and emancipation. A gala followed in the same building at which the Brotherly Union Society26 was presented with a banner from the Black ladies of Hamilton as a token of appreciation for its service to the community. Several other lecturers spoke and, when that segment of the night concluded and the church ministers had left the venue, the dancing began until the early morning.

One month after the Dominion of Canada was formed with the union of Canada West, Canada East, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, the thirty-ninth anniversary of Emancipation Day was commemorated at the St. Paul’s AME Church on Rebecca Street, just east of John Street North (now Stewart Memorial Church). An evening meeting, chaired by the minister Pastor S.C. Chambers, opened with a prayer and was followed by a night of thought-provoking speeches and discussions about the relevance of the day’s observation. Reverend Jones felt that the first of August should not be celebrated with grand public affairs like the parades and other forms of entertainment, but rather by quiet social meetings. Jones believed that other issues were of greater concern to the community such as the establishment and support of community institutions, the promotion of morals and values, and encouragement of independence, all of which should take precedence over partying.

Reverend Abes disagreed with Jones for the reason that Britain’s efforts and God’s intervention needed to be recognized. He also expressed his appreciation of the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes together, a display that symbolized a new, meaningful partnership between two powerful nations. Complete emancipation in North America had been achieved with the abolition of slavery in the United States and Canada was a new country on the world stage, poised to experience growth and change. Perhaps Mr. Jones thought that the province’s African-Canadian community should focus on the future and keep their development in line with the forging of a new nation.

The annual recognition of freedom from slavery also provided the opportunity to witness the accomplishments achieved just one generation after abolition and in spite of racial barriers. At the 1878 August First celebration in Hamilton, Reverend O’Banyoun spoke of how honoured he was to be in the company of a Black lawyer, Mr. Orra L.C. Hughes from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Another example of Black success was the 1884 main speaker, E.H. Morris, the former president of the Chicago Bar Association and member of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Chicago. At events across the province and the country audiences sometimes also received reports on how well some Blacks in the West Indies were doing.

In 1878, about eighteen hundred delegates from Toronto, Brantford, St. Catharines, Bronte, Oakville, and other districts joined Reverend O’Banyoun27 for a parade that marched up James and King Streets. They walked to the Crystal Palace grounds on King Street (present site of Victoria Park) for refreshments and speeches. Orators included the reverend himself; Orra Hughes, the principal speaker; A. Johnston of Nova Scotia; Mr. Collins from Drummondville; and Reverend William Butler28 from Bronte, now a village in west Oakville. Hughes delivered a lengthy, eloquent speech that embodied the common theme, likening the slave history of Africans to the Israelites in Egypt and their deliverance from bondage, which “He regarded as the keystone to the achievement of the grand strides made in the direction of liberty of all kinds ever since,” and also offered three toasts “one for humanity, one for temperance, and one for education.”29

Education was another component of Hughes’ address. He stated that any man who had an impact on the world acquired knowledge by some means and that education would be an important tool for Blacks in dispelling myths of African inferiority, while reclaiming their position as disciplined learners. He went on to provide the examples of the teachings Pythagoras received from an African, the advanced development of the Egyptians, along with modern-day examples of the success of peoples of African descent. Attendees were then treated to some entertainment, and the annual evening ball was held at Pronguey’s Hall on James Street.

This commemoration also illustrated the divergent interests developing between the older and younger parties at these festivities. While the adults were keen on the educational aspect of the gathering, many of the youth did not listen to the speeches. In fact, they “frequently interrupted … talking very loud in the galleries and alongside the platform, so much so that the chairman was constrained to interfere and call for order three or four times.”30 Youth attendance was decreasing and in 1884 the guest speaker said, “There was something he wanted to say particularly to the young people, and he was sorry there were not more of them present to hear him.”31

The Mount Brydges Lodge No. 1865 of Hamilton hosted the fifty-first anniversary of the abolition of slavery in 1884. Member Masons dressed in the regalia of their fraternal order accompanied fellow Masons from Toronto, Amherstburg, London, Chatham, Niagara Falls, St. Catharines, Guelph, Berlin (Kitchener), and Dresden lodges to local hotels and to their lodge hall. Guests from Boston, Massachusetts, Chicago, Illinois, and Rochester and Buffalo, New York, were also present. The street procession, led by a marshal on horseback, began at the Gore (the Town Square) and one thousand participants paraded down the principal streets to Crystal Palace for a luncheon and speeches. George Morton32 presided over the speeches including the guest speaker of the day, E.H. Morris of Chicago. Alderman George Elias Tuckett and Mayor John James Mason both gave addresses.

The special mention of the day was the inclusion of the Hamilton and Toronto branches of the Household of Ruth, “which is composed of the wives and daughters of Oddfellows, who followed in carriages, and looked gorgeous in their regalia of gold braid and black velvet, with tiaras and crowns of glittering tinsel.”33 The group “attracted a great deal of attention” and their drill exhibition, with assistance by the Mount Brydges Lodge, was the highlight of the evening: “The uniformed ones were put through a number of difficult and intricate evolutions.”34

While celebrations carried on throughout the 1890s, by then the attendance of Emancipation Day commemorations started to decline. The way in which the occasion was recognized was evolving. In 1902, a huge crowd of at least one thousand from across southwestern Ontario was expected, but disappointingly, the turnout was less than two hundred. One correspondent observed: “The days of the big demonstration on Emancipation day have evidently departed.”35 Consequently, many of the day’s events were cancelled including the cakewalk, the games, contests, and concerts. Instead of large public demonstrations, smaller events were organized such as the picnic held in 1890 under the auspices of St. Paul’s AME Church. About three hundred children and adults took a boat over to Bayview Park and in the evening the gatherers enjoyed a program by the children at the church, followed by refreshments.36 In 1893, a modest group comprised of people from Hamilton, Bronte, Oakville, Brantford, Guelph, Buffalo, and other centres paraded through some of the main streets of the city led by a mounted marshal and the Oshweken Indian Cornet Band. They then assembled at Dundurn Park on York Boulevard for games, a musical performance by Josephus O’Banyoun’s Canadian Jubilee Singers, and a dress parade at the palace rink. “The attendance was not so large as was expected.”37

The seventy-third anniversary of Emancipation Day was celebrated with a presentation of a cantata, a type of musical play, at Treble’s Hall on John Street North, just north of King Street East, sponsored by St. Paul’s AME Church. The production of “Jephtha and His Daughter” was managed by F.R. Overstreet of Philadelphia, and was enjoyed by visitors from Buffalo, Oakville, and Toronto.38

August 1, 1909, passed without much fanfare, likely only some small-scale meetings at local Black churches or in private homes, but no public events. By this time very few former slaves were alive in Hamilton, a reality that was depreciating the meaning and importance of the freedom festival. Other large cities and smaller towns that once hosted elaborate Emancipation Day observances were experiencing a similar decline.39

In the new millennium, the uncovering of some of Ontario’s deep, rich African-Canadian history in places like the Dundas Valley is leading to the restoration of August First as a day of commemoration of the end of slavery. Emancipation Day was first recognized at the Griffin House in Ancaster in 2002 after the history of the property, purchased by the Hamilton Conservation Authority, was unearthed. Just ten kilometres outside of Hamilton, Griffin House, was the original home and eighteen-hectare property of Enerals Griffin,40 a fugitive slave who arrived in Ancaster in 1830. Anne Jarvis, who initiated the observances, has organized programs that have included the reading of an account from the Hamilton Spectator of Emancipation Day celebrations at Auchmar Estates and inviting speakers such as locals who were interested in Black history to speak on the occasion as well as members of the Central Ontario Network for Black History.

Oakville received a sizeable number of fugitive settlers who entered Canada on the Underground Railroad with the assistance of White and Black residents of Oakville who engaged in anti-slavery activity. Captain Robert Wilson was a White abolitionist who transported escaping slaves to freedom by stowing them away in grain shipments aboard his fleet of small vessels or his main ship from American ports in New York. Two other captains, George Hardy Morden and James Fitzgerald, were also known to have carried refugees across Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Former slave James Wesley Hill became an agent on the Underground Railroad once he secured his own freedom in Upper Canada in the late 1840s. He had rescued so many fugitives over several trips back to the United States and bringing them to safety in Canada that he earned the name “Canada Jim.” Hill would then employ the refugees on his strawberry farm.41 Some moved on to other Black settlements in the province, while others took up permanent residence in Oakville finding work as domestics, dockside workers, and farmers. One gentleman, John Cosley, published a local newspaper called The Bee.

In 1891, these refugee settlers and free Blacks also established an AME church with William Butler as the minister. It is now known as the Turner AME Church, named after Bishop Henry Turner, a church minister and community activist. President Abraham Lincoln designated him chaplain to the United Stated Armed Forces, the first African American to achieve this position. The church congregation included residents from Oakville and Bronte, with a mix of AME and BME followers. The religious institution also served as a community centre. Many social activities such as musical concerts, parties, banquets, and other celebrations took place there or were organized by the congregation.42

Celebrating citizenship as a British subject and the opportunity for an improved quality of life motivated African Canadians in Oakville to observe Emancipation Day. Beginning in the 1850s with the influx of self-emancipated African-American slaves, regular celebratory picnics were held in George’s Square, a park located at Trafalgar Road and Sumner Avenue. Local African Canadians and many who previously lived there returned to commemorate the end of slavery. It was an annual tradition to march about one kilometre northwest of George’s Square in a street procession up to “Mariner’s Home,” the house of Captain Wilson, to pay homage to the man who had helped them or their ancestors. August First commemorations gradually declined by the early twentieth century, which was reflective of the decreasing Black population. “As the years passed, the number of visitors dwindled until one year only one man climbed up the steps to Captain Wilson’s door. The following year none came.”43

However, events did take place intermittently as noted in a 1929 newspaper article that stated: “For the first time in many years, Emancipation Day was celebrated by the colored race here.”44 The assembly was organized by the AME church who hosted a garden party at Victoria Park. Guests came from Toronto, London, Hamilton, and St. Catharines to mark the occasion. The activities included a girl’s softball game, speeches, and musical performances by the Oakville Male Quartet, the town band, and duets by Al and Bob Harvey of Toronto. Mayor Thomas Blakelock, chairperson of the day, gave opening remarks before turning the podium over to the keynote speaker, Bertrand Joseph Spencer Pitt, the attorney from Toronto who at that time spearheaded the “Big Picnic” in St. Catharines. Pitts’s address focused on Britain’s decision to make slavery illegal and congratulated the country for its efforts in abolition.45

Alvin Duncan, a descendant of fugitive slaves and a Second World War Royal Canadian Air Force veteran, recalls “marking Emancipation Day in August with a picnic in George Street Park,” when he was young. 46 Today, the tradition has been revived by the Canadian Caribbean Association of Halton (CCAH) in partnership with the Oakville Museum at Erchless Estate. Since 2007 people gather at St. George’s Square for a family-oriented picnic, while recreating history in celebrating the historic role Oakville played in securing the freedom of many people.

The diverse population of early Toronto (called York until 1834) consisted of Africans of varying backgrounds. Some of the city’s first Black inhabitants were enslaved Africans, the chattel property of British colonists and Loyalists settlers. Slave owners included Peter Russell, the administrator of Upper Canada, and William Jarvis, the first sheriff of York. There were about four hundred people of African descent living in Toronto. As a bustling city centre and a terminus of the Underground Railroad during the middle of the nineteenth century, Toronto also attracted many African-American fugitives. By the early 1860s, over two thousand refugees lived in Toronto. Free Blacks, who were locally born, immigrants from the United States, and a few from the Caribbean also resided in the city, especially after 1850 with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act.

These Black pioneers possessed a variety of skills and abilities. Some were educated professionals, owned real estate, and operated numerous businesses such as barbershops, grocery stores, restaurants, a salon, a cab company, a livery-stable, an ice company, a carpentry business, a cobble shop, a ladies dress and accessory shop, and a hardware store/ sawmill. Others found work constructing roads, and others as porters, farmers, bricklayers, sawyers, plasterers, blacksmiths, carters, waiters, washerwomen, domestics, and dock workers. Some widows made a living by operating boarding houses. The opportunities afforded enabled them to fare well economically.

They founded significant community institutions including businesses, churches, social reform societies, and political organizations. The churches established included the longstanding First Baptist, which was established in 1825 by Elder Washington Christian, initially located at Victoria and Queen Streets (site of St. Michael’s Hospital today) before moving to D’Arcy Street in 1955. An African Methodist Episcopal Church formed at Richmond Street east of York Street first moved to Elizabeth Street, then to Sayer (now Chestnut Street) and Elm Streets, and is now on Soho Street. A Baptist Church on Teraulay Street and a British Methodist Episcopal church on Chestnut Street were established, and the Coloured Wesleyan Methodist Church was organized in the 1830s on Richmond Street, with the assistance of Wilson Ruffin Abbott, originally from Alabama and by then a wealthy businessman.

The Provincial Union started a Toronto chapter in 1854, led by Thomas F. Cary, the husband of Mary Ann Shadd Cary, and Wilson Abbott, father of Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott. The chapter offered services and programs to refugees. Black women established groups like the Queen Victoria Benevolent Society, founded by Ellen Toyer Abbott (mother of Anderson Ruffin Abbott), the Ladies Freedman’s Aid Society, and the Society for the Protection of Refugees. These associations primarily helped fugitives coming into the urban centre.

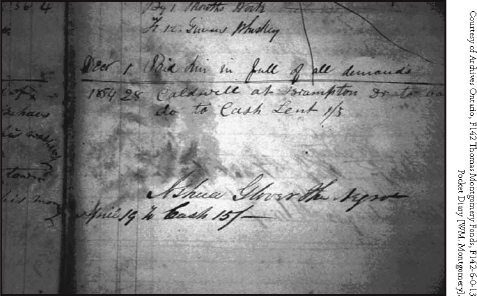

One notable example of a fugitive was Joshua Glover.47 On April 19, 1854, a travel-worn Black man trudged into Montgomery’s Inn on Dundas Street in Etobicoke. He was hungry and homeless. Two years before Joshua had escaped slavery in Missouri and settled in the free state of Wisconsin. However, his former owner tracked him down and had him imprisoned in Milwaukee, pending his return to Missouri. Enraged Wisconsin citizens stormed the jail, and on March 11, 1854, Joshua Glover disappeared on the Underground Railroad. For four weeks he was concealed in barns, attics, and cellars around the Wisconsin countryside. Finally, he was smuggled aboard a ship in Racine, Wisconsin, and sailed for the security of Canada West. On that wonderful spring day in 1854, Thomas and William Montgomery (usually the most cautious of businessmen) lent this stranger fifteen shillings, and recorded the loan in their account book. They offered him work and shelter, and Joshua Glover lived the rest of his life in Lambton Mills on the Humber River, in a house rented from the Montgomery family.

This telegram was sent from the superintendant of the Industrial House in Newmarket (the Poor House of York County) to William Montgomery, a businessman in Islington. Due to complicated circumstances, Montgomery was never able to locate Glover’s body.

The presence of a sizeable fugitive population coupled a large number of Whites with strong anti-slavery feelings facilitated a wide array of activities in support of the cause. St. Lawrence Hall at Jarvis and King Streets was the venue used to host abolitionist speakers like Frederick Douglass, was the site of the meeting that formed the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada, and, on September 10, 1851, hosted the North American Convention of Coloured People.48

Several legal challenges to American slavery took place in the courts of Osgoode Hall located at Queen Street and University Avenue such as the 1861 John Anderson extradition case that was tried by Chief Justice John Beverly Robinson. Anderson was subsequently set free after an appeal to the British courts. In reverence to the “Great Emancipator” Abraham Lincoln — the man they perceived as having legislated freedom for African Americans with the Emancipation Proclamation of 1865 — Black Torontonians closed their businesses during Lincoln’s funeral, held memorial services at several churches, and wore a Black armband for eighty days as a symbol of mourning.

A few newspapers using their pages to fight slavery were based in Toronto. The first office of the Black newspaper, the Provincial Freeman, was located at King and Jarvis Streets from 1854 to June 1855, and the Toronto Globe, published and edited by George Brown, also operated in Toronto. Brown was a staunch abolitionist and opposed racism. He, like the editors of the Provincial Freeman, used his paper to dispel stereotypes of Blacks, promote anti-slavery ideals, publicly denounce American slavery, share editorials on the atrocities of slavery, discuss the problems of runaways in the province, and provide reports on Emancipation Day celebrations in Toronto. Of anti-slavery in the city, Samuel Ringgold Ward, Black abolitionist and founder of the Provincial Freeman, said, “Toronto is somewhat peculiar in many ways, anti-slavery here is more popular there than any other city I know save Syrcuse [sic] …”49

Blacks in the Toronto of that period experienced fewer incidences of blatant racism and seem to have been more accepted by their White neighbours. William P. Newman, one-time editor of the Provincial Freeman stated: “Here there is no difference made in public houses, steamboats, railroad cars, schools, colleges, churches, ministerial platforms, and government offices. There is no doubt some prejudice here, but those who have it are ashamed to show it. This is at least true of Toronto.”50 A White traveller from the United States observed that Blacks and Whites worshipped together without distinction in several churches that had White and Black clergy. However, that does not mean that there was an absence of serious racial problems. Dr. Daniel Hill speculates that because the Black population remained fairly stable and did not increase drastically in a short time frame as in some towns in southern Ontario, there was less prejudice.

Still, Black Torontonians experienced discrimination and challenged occurrences of racism collectively and individually when they arose. For example, members of Toronto’s African-Canadian community protested against minstrel shows that travelled to the city. White actors would paint their faces with Black makeup and perform songs, skits, and plays that disparaged Africans. In 1840 they successfully petitioned the city council to not allow companies that exhibited these acts to perform in the city. Visiting Blacks were denied hotel accommodations such as in two cases documented in 1888 and 1929. Black voters in Toronto protested two racist politicians, once against Colonel John Prince’s racist comments in 1857 and the other in 1864 against a city councillor who persisted on “calling them niggers.” A Black passenger on a boat sailing from Toronto to Kingston was not permitted to enter the captain’s dining room. One exception to racial discrimination in Toronto, different to many other towns in Ontario, was that their children attended integrated public schools, colleges, and universities in Toronto. Graduates of Toronto’s integrated schools included Emaline Shadd, Peter Gallego, Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott, Dr. Alexander Augusta, and William Peyton Hubbard. Emancipation Day commemorations were also intertwined with the cultural, social, religious, and political lives of African Canadians in Toronto.

Community leaders and business owners organized the celebrations and festive events convened in many of the Black establishments. J.R. Kerr-Ritchie discusses that from the 1830s through to the 1850s, the Black elite who assumed leadership on behalf of all African Canadians planned August First events in Toronto.51 He further identifies two different kinds of Black Emancipation Day organizers and celebrants. The first group was made up of early Black Loyalists who established the older Black communities in the larger centres of Brantford, St. Catharines, Niagara, Hamilton, and Toronto. They instituted celebrations from 1834. The second group was comprised of the population of new fugitives who arrived in the 1840s and 1850s and settled in the southwestern Ontario towns of Chatham, Raleigh, Harwich, Camden, Amherstburg, Colchester, Sandwich, and Windsor. These Blacks in Kent and Essex counties commenced freedom festivals upon their arrival. Kerr-Ritchie’s comparison of how these two groups recognized Emancipation Day reveals the diversity of ideas and political views among Black Ontarians.

An examination of Emancipation Day in the identified southeastern Ontario cities during the first half of the nineteenth century reveal elements of an Anglo-Canadian identity such as volunteering for military service, strong political support of the Conservative party, the adoption of British cultural customs such as drinking tea, close ties to the Anglican church, and public displays of patriotism, especially on August First. The recent fugitives in southwestern Ontario in the mid-century used Emancipation Day celebrations initially to show loyalty to Britain then later as a tool to engage people in the movement to end American slavery. This shift in the use and meaning of Emancipation Day brought about by the fugitives shows strong anti-slavery beliefs that created, changed, and influenced elements of African-Canadian culture through the incorporation of African-American customs, militancy, and the formation of new institutions such as a Black press, AME churches, and self-help societies.

The legislation that ended African slavery in British possessions was celebrated publicly in Toronto as early as 1838 and has carried on regularly since then. Black Torontonians found cause for celebration on August 1, 1838, when Jamaica ended the apprenticeships of former slaves two years earlier than expected. They celebrated again that year to mark the final emancipation of slaves in the British Empire. Community members attended a special church service at St. James’ Cathedral Anglican, at Church and King, and Archdeacon John Strachan delivered a fitting sermon. Those assembled then ate a celebratory dinner.52

The Toronto Abolition Society, an association formed in 1833 that sponsored Emancipation Day commemorations in the 1830s and 1840s, organized the city’s 1839 celebration. A church service was performed at the AME Church at Richmond and York Streets, where a Reverend William Miller from Philadelphia delivered the sermon. After that, the crowd formed a parade and marched to city hall, which then was located in the south building of the St. Lawrence Market at Front and Jarvis Streets. Various speakers, such as Mayor John Powell, a Conservative politician, addressed the celebrants. Reverend Henry James Grasett,53 minister of the St. James Cathedral, also delivered a speech on British West Indian emancipation. Marchers then went on to the Commercial Hotel at Front and Jarvis Streets for an elaborately decorated feast. A British flag was hung in honour of the day. Jehu Jones of Philadelphia, the first ordained Black Lutheran minister in the United States, was invited by William H. Edward of the Toronto Abolition Society to join the celebration the day he immigrated to the metropolitan. In a letter to Charles B. Ray, editor of the Colored American, he describes how inspired he was by the seemingly prejudice-free environment he observed in Toronto:

Reverend Henry James Grasett, rector of St. James’ Cathedral (1847–1882). Prior to this post, he was the assistant to John Strachan, Archdeacon of St. James’ Cathedral, from 1835 to 1847.

The kingdom of Great Britain is open to all men where life, liberty, and the pursuits of happiness, without dissimulation, is distributed with an equal hand, to all men, regardless of the country or condition of any. This province especially, seems to invite colored men to settle down among the people, and enjoy equal laws. Here you need not separate into disgusting sect of caste. But once your elastic feet presses the provincial soil of her Britannic Majesty, Queen Victoria, God bless her, you become a man, every American disability falls at your feet — society — the prospects of society, holds out many inducements to men of capital; here we can mingle in the mass of society, without feeling of inferiority; here every social and domestic comforts can be enjoyed irrespective of complexion.54

The Black women of the city hosted a tea party in the evening at one of their homes on Elizabeth Street, to which Jones was invited. This is a demonstration of the adoption of British habits by African-Canadians in Toronto. He would remain in the city and live in Toronto for three years before returning to the States.

For the tenth anniversary of the abolition of slavery, St. James’ Cathedral was again the central meeting place. The day was recognized with a street procession to the church for a religious service delivered by Reverend Grasett and was followed by a party in the evening.55

As part of the 1854 recognition of Emancipation Day, a thanksgiving service was held at the Second Wesleyan Chapel at five in the morning. It was followed by a parade marshalled by W.H. Harris, C.P. Lucas, and W. Thompson, which began at the Government House on King Street West. This was the official residence of the governor general of Canada West (Ontario), which at that time was the Right Honourable James Bruce. Participants marched to Brown’s Wharf (the Yonge Street Wharf ) to meet arriving guests sailing from Hamilton on the Arabian. Here Thomas Smallwood Sr.,56 one of the organizers and elected president of the day, addressed the arriving crowd.

Fellow subjects of this noble province, and citizens of Hamilton, It is my pleasing duty, in behalf of a portion of my fellow citizens of Toronto, to welcome you, who have honoured us this day with your presence, to partake of a festival in commemoration of one among the greatest events in British history, when that magnanimous nation swept the bonds from 800,000 bondsmen, and made them free. Though some narrow-minded individuals object, saying, because we did not achieve it ourselves, it is disgraceful for us to celebrate this day; I am assured by your presence here to-day, that I speak your sentiments, when I say that I envy not the narrowness of the mind that can entertain such disloyal sentiments; so you are therefore heartily welcome to our hospitality.57

Afterwards the group continued on to St. James Cathedral to hear the special sermon delivered by Reverend Grasett, the regular speaker at Emancipation Day observances. Celebrants continued to march through the city to the Government Grounds on Front Street, between John and Simcoe Streets, for a grand banquet. After dinner, a program of speeches and entertainment began. The organizing committee asked George Dupont Wells, a local White lawyer, to read a speech they had written and dedicated to Queen Victoria expressed the gratitude of Toronto Blacks for Britain’s abolition efforts. (See Appendix A.)

Mary Ann Shadd of the Provincial Freeman returned to Toronto from a southwestern Ontario tour in time to briefly address the crowd. It’s not known what she said, but since Shadd had recently come back from soliciting newspaper subscribers, it is likely that she approached the gatherers with the same request. The evening was capped off with a fireworks display that was accompanied by a musical band. White residents of Toronto were involved as participants and observers in August First holidays. Some, like Reverend Grasett and Wells, lent support by being part of the activities, while other locals watched the parades along the main streets or attended some of the various events.58

Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott, the first Black, Canadian-born doctor, describes one of Toronto’s Emancipation Day commemorations in the 1850s:

On one occasion within my memory they provided a banquet which was held under a pavilion erected on a vacant lot running from Elizabeth Street to Sayre Street opposite Osgoode Hall, which was then a barracks for the 92nd West India Regiment. The procession was headed by the band of the Regiment. The tallest man in this Regiment was a Black man, a drummer, known as Black Charlie. The procession carried a Union Jack and a blue silk banner on which was inscribed in glit letters “The Abolition Society, Organized 1844.” The mayor of the city, Mr. Metcalfe, made a speech … followed by several other speeches of prominent citizens. These celebrations were carried on yearly amid much enthusiasm, because it gave the refugee colonists an opportunity to express their gratitude and appreciation of the privileges they enjoyed under British rule.59

Kerr-Ritchie argues that observances in Toronto and other major centres were more of a display of colonial patriotism by Black Loyalists who were freed by a benevolent state versus celebrations in southwestern Ontario towns that were freedom festivals in the true sense of the term by self-emancipated African peoples. The public display of allegiance and appreciation to Britain by both kinds of celebrants usually took the form of a street procession.

On August 1, 1856, African Canadians in Toronto took to the streets. The procession formed on College Avenue and marched down to the Great Western Railway Station on Front Street (now Union Station) to receive visitors from Hamilton. The parade resumed with everyone marching east along Front, north on Yonge, east on Wellington, then north on Church to St. James’ Cathedral. Reverend Grasett delivered a suitable sermon for the day after which the procession rejoined, led by an all-Black brass band, and continued to parade along various streets back to College Avenue for a tent lunch.60

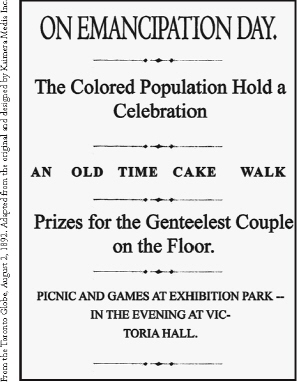

A replica of the advertisement for a dance held for the 1892 Emancipation Day celebration in Toronto. The cakewalk, developed by enslaved Africans on southern plantations, was a mix of traditional African circle dances and European dances, initially created to mock their White masters and mistresses. It became a popular dance across North America and internationally.

There were no celebrations in Toronto in 1859, quite likely because many Black Torontonians attended the huge festival in Hamilton. It was practice for African-Canadians in Canada West to support Emancipation Day observances in other parts of the province as a show of solidarity and community strength. But there was an August First demonstration in Toronto in 1860 that began with a church service at St. James Cathedral where Reverend Grasett once again delivered a sermon for the occasion. Celebrants then attended the leisure activities at Exhibition Park and a dinner and dance in the evening.61

On August 1, 1883, the forty-ninth anniversary of the Abolition Act of 1833 was put together by the Toronto branch of the Peter Ogden Lodge of the Grand United Order of Oddfellows, one of the few Black lodges established in Canada. The customary procession formed on Temperance Street headed by the Peter Ogden Lodge members and was followed by the Mount Brydges Lodge of Hamilton and the Victoria Lodge of Toronto. In front was the Excelsior band of Toronto, under the direction of Captain Jack Richards, who, like “Black Charlie” thirty years before, wore a blue and gold suit. Richards was also the drum major. Participants marched north on Yonge to Queen, then south on York Street to the wharf where they boarded a Turner ferryboat for Exhibition Park. Sporting activities and games in the afternoon included a half-mile race, a hopping race, a three-legged race, a half-hour race, and a hop, step, and jump competition. The amusement activities were followed by addresses by several Toronto and out-of-town notables.62

An interesting inclusion to the evening proceedings of Toronto’s 1892 celebration held in Victoria Hall was the cakewalk. A prize, two large cakes, was awarded to the lady and gentleman displaying the most grace and charm while circulating the hall — the “genteelist” man and woman on the dance floor.63

The Peter Ogden Lodge played a major role in organizing the celebrations in 1892 as well. Members always marched in the parades alongside other lodges, associations, and societies. Part of the reason for their consistent involvement with Emancipation Day is found in the basic principles of the Order: “to obtain an honest livelihood, to be faithful to our Queen and country, to avoid turbulent measures, and to submit with reverence to the decisions of a Legislative Authority.”64 These shared objectives were part of the purpose of Emancipation Day observances.

Toronto did not host large Emancipation Day festivities every year. As was custom, the towns and cities that recognized August First took turns in holding large-scale events, and the various African-Canadian communities planned and coordinated with one another to make travel and accommodation arrangements. In 1895, for example, a newspaper article read:

This is Emancipation Day, but local colored people are not indulging in any celebration. A number of the younger men of the Peter Ogden Lodge of colored Oddfellows, which organization has usually had considerable to do with the celebration of Emancipation have left the city and the old members who are left have not the … to have a big time like the young brethren. There is a big gathering of colored people to-day in London.65

And in 1902 several hundred Blacks from across the province, including Toronto, converged on Hamilton to commemorate Emancipation Day. By the 1920s, St. Catharines was the primary celebration site and people from Toronto attended regularly, taking one of two steamers across Lake Ontario to Port Dalhousie. The end of that eventful era saw public Emancipation Day gatherings return to Toronto and take on a new face.

During the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, Toronto was a site of civil rights activism. The demographics of the city’s Black community had changed to include immigrants of African descent from the Caribbean, some as university students and some as female domestics. The newcomers encountered prejudice and racism in their daily lives, in obtaining employment, in finding a place to live, and in many other aspects of life. August First provided citizens of the city who fought for equality for all to publicize the injustices taking place and to mobilize like-minded people to advocate for change. Local Black churches, as they had in the early observances of the 1800s, were active in mobilizing the community for the day. Dr. W. Constantine Perry of the city’s AME Church used the occasion and radio waves to speak out against the discrimination levied towards Black nurses. In a radio interview on CKEY, Perry discussed the issue of the barring of women of African descent from working as nurses in hospitals in Toronto and other cities like Windsor:

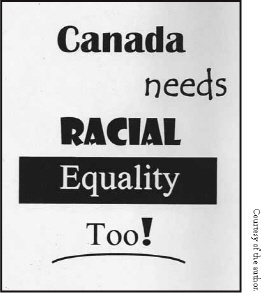

The Civil Rights Movement was alive and well in Canadian cities and towns. African-Canadians and other minority groups fought for equal opportunities and equal access. Shown is a replica of a placard carried by marchers on Emancipation Day in Toronto on July 27, 1964.

At the present time there exists an alarming situation in the shortage of nurses in our hospitals, a shortage which would not have been so great except for discriminatory indulgences,” said Dr. Perry. His address was in connection with the celebration of emancipation of Negro slaves in British colonies …66

Reverend Perry also made radio addresses in 1947 and 1951 that pointed to the discrimination against people of African ancestry in Canada.67 In Windsor, “Mr. Emancipation” Walter Perry used the Progress magazine to bring awareness to and congratulate the Black women who were still pursuing a career in the nursing profession despite the employment discrimination. The first issue of the publication in 1948 featured two women from Windsor and Dresden, the first African-Canadian students to gain admission to the nursing program at Windsor’s Hotel Dieu Hospital. The 1950 edition recognized the first Black graduate from that program, Cecile Wright.

Beginning in 1953, freedom events were held under the auspices of the Toronto Emancipation Committee (TEC). The revival of Emancipation Day observances in Toronto were spearheaded by Donald Moore, who pulled together numerous local Black community groups, churches, fraternal orders, and leaders under the umbrella of the TEC. Moore asserted that:

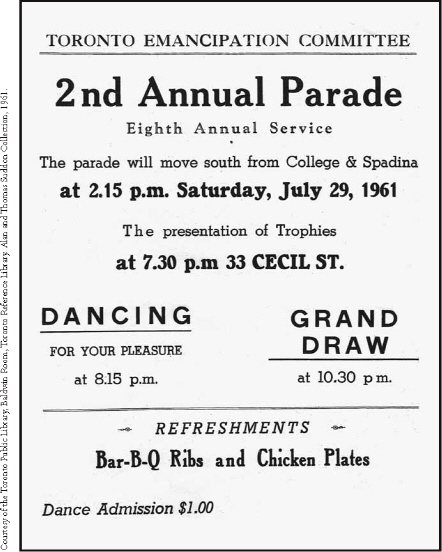

The Toronto Emancipation Committee organized Emancipation Day commemorations during the Civil Rights era.

Every facet of the community became involved: the churches — African Methodist Episcopal, British Methodist Episcopal, First Baptist; the lodges — Peter Ogden Lodge No. 812, Grand United Order of Oddfellows, Victoria Household of Ruth N. 5354, Eureka Lodge No. 20 Free and Accepted Masons, Naomi Chapter No. 8 Order of Eastern Star, John Henry valentine Lodge No. 740 Improved Beneficial and Protective Order of Elks, Queen City Temple No. 1003, IBPOE; associations – Universal Negro Improvement Association, The Home Comfort Club, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the Ladies Auxiliary Pullman Division, and the Toronto Negro Women’s Club. Also involved were the Toronto Negro Veterans under President Jim Marson and Treasurer Edward Clarke, and the Toronto Veterans Colour Guard under Commander Sergeant Aubrey Sharpe, E.MC.D.68

They used the August First holiday to commemorate the abolition of slavery and to pay tribute to the Black men who served in the Canadian military, from the Coloured Corps who fought in the War of 1812 to the men who served in the Second World War. The intent of the memorial service was:

• To offer thanks for emancipation from slavery.

• To pay due respect to those who laboured unselfishly to bring it about.

• To place a wreath on the cenotaph to our glorious dead who gave their lives in defence of Canada.

• To look forward with love and determination to remove those scars which slavery has left.

• To gather strength for the road ahead.69

In his memoir, Moore detailed the typical format of an August First program at Victoria Memorial Park at the end of a street procession, which consisted of opening prayers by church ministers followed by speeches by local community members, Black and White. These speakers included the likes of Stanley Grizzle, citizenship court judge and one-time president of the Toronto chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Black community activist Esther Hayes; John Collingwood Reade, CFRB radio host; and a wide array of Toronto-based, and national lecturers. Speakers discussed the ongoing struggle for freedom and equality, the importance of education, and the vigilance that was needed to maintain and extend universal freedoms. Another characteristic feature was the receiving of greetings from politicians at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels like the Honourable Lester B. Pearson and John Wintermeyer, national leader of the Liberal party and the Ontario Liberal leader, respectively. The TEC also used the opportunity to publicize the racial inequality African Canadians continued to experience through the selection of appropriate speakers.

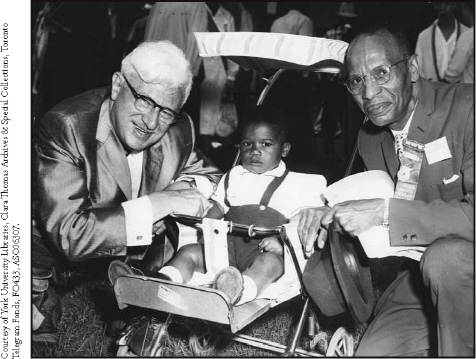

Community activist and Director of the Negro Citizenship Association, Donald Moore (right), with Mayor Nathan Phillips (left) and seventeen-month old Eugene Hood at Victoria Memorial Park on August 1, 1960.

When Donald Moore addressed the audience himself in 1954, he talked about the entrenched racism faced by people of African descent from the period of enslavement to the current discriminatory immigration practices against Blacks from British territories. He stressed the importance of remembering the past — where Blacks have come from and the journey to get here — in order to know future direction. Moore then reminded the crowd to call upon the endurance and resilience of their ancestors at the time of battle, such as the challenging of Canada’s immigration policies. In closing, he asserted, “Today we cannot be content with being wards of society. We must share in the responsibilities of citizens and see that no one prevents us from sharing in its glories.”70 His speech encapsulated themes that have persisted since the inception of Emancipation Day commemorations, indicative of the racial inequality that every generation encountered, even 120 years of the passage of the Emancipation Act.

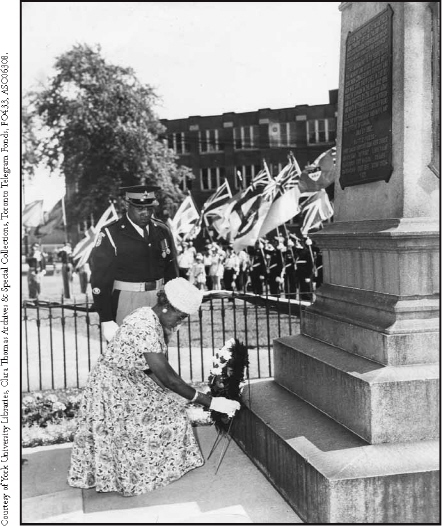

Sergeant Aubrey Sharpe of the Toronto Negro Colour Guard War Veterans and the young Beatty brothers at the Victoria Square cenotaph on August 1, 1957. As part of Emancipation Day commemorations sponsored by the Toronto Emancipation Committee, wreaths were laid at the war memorial park in memory of the many African-Canadian soldiers who died defending Canada in the Coloured Corps (War of 1812), the First World War, and the Second World War.

Silver Cross mother, Edith Holloway, places a wreath at the cenotaph at Victoria Memorial Park on August 1, 1960. She lost her son in France during the Second World War. Beside her is Jim Marson, Warrant Officer II of the Toronto Negro Veteran Association Drill Team.

The Emancipation Day parade in Toronto, July 29, 1961, led by the Toronto Negro Band. The procession is arriving at Victoria Memorial Park at Niagara and Portland Streets.

In 1958, the invited guest speaker was attorney Violet King,71 the first African-Canadian woman admitted to the bar in Canada, who told the crowd of over one hundred “that you cannot legislate against prejudice, but you can legislate against discriminatory acts which further prejudice.”72 This was a powerful message coming from a Black attorney. Just as in the United States, African Canadians were seeking to bring about social change through the implementation of human rights legislation, including an overhaul of the immigration laws, equal admission to nursing programs, and access to employment opportunities.

Seven years later, in 1964, over six hundred paraders and observers participated in the eleventh annual commemoration with a procession from Lansdowne Public School, down Spadina Avenue, to the Victoria Memorial Park on Wellington Street West.73 Many of the marchers held signs that called for racial equality in Canada, and were accompanied by several bands including fife and drum bands of the Orange Order and several army and veteran bands. The crowd listened to a speech delivered by Rabbi Abraham Feinburg that promoted racial harmony and special honour was paid to the Black servicemen who fought and died in the War of 1812 with a memorial service in the park.

The West Indian immigrants who settled in Toronto in the mid-1900s introduced the carnival feature to the celebration of Emancipation Day with the establishment of Caribana in 1967. Rooted in the carnival in Trinidad, the forty-two year old event includes a huge parade with the colourful representation of many Caribbean islands, including Guyana, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, and Brazil. It is a mainstay cultural festival that draws thousands of local and international spectators annually over the long weekend to downtown Toronto to enjoy the costumes, dance, music, art, and food of the West Indies. While the roots of the festival are a distant memory and not known to many of the revellers, some aspects of the Caribbean style of celebrating Emancipation Day remain present.

In 1996, the Ontario Black Historical Society (OBHS) revived the annual celebration and it has continued yearly. Events have been held on August 1st at the Parliament Building, Queen’s Park, and at Nathan Phillip Square.74 Since then, Rosemary Sadlier, president of the OBHS, has been advocating for legislation at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels to proclaim August First as Emancipation Day. To date there has been some measure of success. In 2008, official recognition came from the provincial government making the first of August Emancipation Day in Ontario.