To be free means the ability to deal with the realities of one’s situation so as not to be overcome by them.

— Howard Thurman, Meditations of the Heart, 1953.

Owen Sound, located on the southern shores of Georgian Bay, was the northern most “station” of the Underground Railroad. Blacks who arrived in this part of Grey County (often by steamer or wagon) settled in the nearby communities of Negro Creek, Priceville, Virginia (now Ceylon), Holland Centre, and Nenagh. Some African Americans who had settled first in Queen’s Bush relocated to the Owen Sound area in the 1850s. It is believed that some of them settled along the Old Durham Road, which runs just south of the former Highway 4 running in a westerly direction from Flesherton through Priceville towards Durham. Ongoing research in the area has determined that a number of the lots along this road were initially cleared by Blacks seeking to set up homesteads. The Old Durham Pioneer Cemetery, located at the intersection of the Old Durham Road and Grey County Road 14, is where many of these people were buried. Several stories are told of the rise in prejudice and discriminatory practices that escalated as the English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants moved into the region; there were even rumours of Ku Klux Klan activities. As result, many of the Black pioneers moved out, some heading further north to the Owen Sound or Collingwood areas.

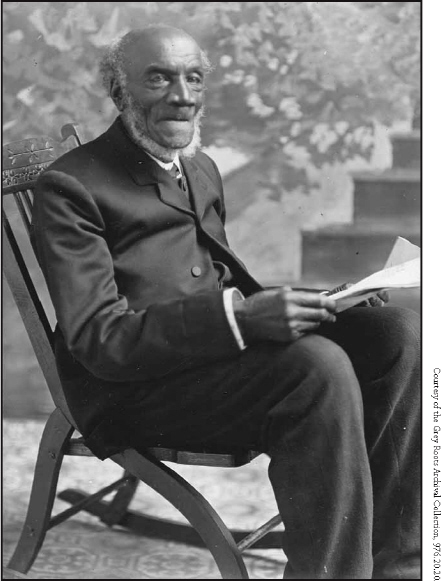

Father Thomas Henry Miller, lay preacher, Little Zion Church (BME) in Owen Sound.

More recently, some members of the local Old Durham Road Pioneer Cemetery Committe1 undertook a restoration project involving extensive research on the Black history of the area and archeological explorations of the site. As a result, the few old cemetery gravestones that could be located were returned to the cemetery, and in 1990 the Old Durham Road Pioneer Cemetery was restored and rededicated by Lincoln Alexander, then the lieutenant-governor of Ontario. Today it is marked as an historic site.2

These women were members of the BME Church in Owen Sound around the early 1900s, back row (l to r): Pearl Green, Myrtle Green, Viola Johnson, and Ethel Earll; front row seated (l to r): Josephine Scott, Georgina Douglas, and Elizabeth Harrison.

These freedom seekers worked to clear land in Grey County, establishing homesteads and securing as positive a life for themselves and their developing community as was possible. To do so they established their own institutions to assist one another and to strengthen their community.

The “Little Zion” BME Church, at the present-day site of Market Square in Owen Sound, was started in the early 1850s by Reverend Thomas Miller, son of a slave. Later, Josephus O’Banyoun came to take over the responsibilities of the church in 1856. Blacks in Owen Sound established close social ties with those living in Collingwood, almost sixty kilometres to the east, as a way of extending their support system in a new, free land. It was a tradition for Black residents of Owen Sound and of Collingwood to support each others’ Emancipation Day celebrations. Many would walk from Owen Sound to attend the festivities at Georgian Bay Park in Collingwood.

Thomas Henry Miller, the preacher of the BME church, spearheaded celebrations in 1856. James “Old Man” Henson, an escaped slave from Maryland who settled in Owen Sound in the late 1840s, regularly provided a detailed depiction of his recollection of slavery and his escape from bondage in the United States to John Frost Jr., enabling Frost to write Broken Shackles in 1889 under the pseudonym of “Glenelg.”3 John “Daddy” Hall,4 one of the first Black settlers in Owen Sound, announced Emancipation Day celebrations and other town happenings in his capacity as town-crier, a role he had for fifty years.

Prior to obtaining Harrison Park as the permanent location for the occasion in 1912, members of Owen Sound’s Black community travelled by steamer to the waterside village of Leith on the northeast shore of Georgian Bay and to Presque Isle north of Owen Sound in the former Sarawak Township to commemorate August First celebrations.

On one occasion, sometime between the 1870s and the 1890s, participants from Owen Sound took a steamer to Presque Isle to attend the observance held under the auspices of the BME Church. White Methodists ministers and some of their congregation from Owen Sound were part of the group of celebrants as well as local residents of Presque Isle. Superintendant of the Sabbath school, Mr. S. Graham, presided. James “Old Man” Henson was given a warm reception when he was called upon to speak to the gatherers. He shared a few insightful anecdotes on separation based on race, and pointed out how things were changing; an example being that particular day when both Black and White men and women were having a good time together. Reverend Miller addressed the assembly and provided some background on the abolition of enslaved Africans. He extended gratitude to members of the White community for joining them in the celebration and for helping the church’s Sunday school. Speeches were also delivered by W.P. Telford, Reverend Kerr, and Reverend Holmes. Captain Ludgate performed a musical solo of the hymn, “I am satisfied with Jesus Now.” The event closed with a brief concert by the choir before returning to the shores of Owen Sound.5

Annual activities at Harrison Park in the early 1900s were comprised of cookouts, games, races, musical performances, and readings alongside the Sydenham River. The Eastern Star Lodge and Masonic Lodge of Owen Sound helped to organize, sponsor, and promote the events in both Owen Sound and Collingwood. Called “the longest continuous running Emancipation Day celebrations in North America,” this annual tradition has continued through into the twenty-first century, changing and adapting to attract a large, diverse audience. Some gatherers visit to get together with family and friends, while others who are less familiar with the festivities attend to learn more about this part of Ontario’s and Canada’s Black history.

Drew Ferguson (left), Mayor of Owen Sound Ruth Lovell, and Mario C. Browne (MPH, CHES) Project Director, Center for Minority Health, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, at the Emancipation Day festival at Harrison Park, Owen Sound, 2007.

Owen Sound’s Emancipation Day held its 147th event in 2009. Now a three-day festival organized by Dennis Scott, a native of Owen Sound, and his wife Lisa, along with an ensemble of volunteers, the event serves to educate and enlighten people through a range of programming including art exhibits that feature the works of African-Canadian artists at Grey Roots Museum and Archives, a lecture series, book launches, and readings, all supplemented by a variety of African-influenced music. In 2008, a cycling tour of bike riders from the United States honoured the escapees and agents of the Underground Railroad by travelling on some of the arteries taken en route to Canada. This tour may become a new tradition. The annual picnic held on a Saturday at Harrison Park, situated off Second Avenue, is filled with even more activities, music, storytelling, craft presentations, games, races, and award presentations, and is a cherished tradition in the life of Owen Sound.6 Now an international event, the annual celebration attracts visitors from all over Ontario and parts of the United States.

Blacks settled in a portion of the Queen’s Bush as early as 1833. This yet-to-be-surveyed territory was located southwest of Lake Huron and included parts of present-day Wellington County and Waterloo County, as well as today’s Dufferin, Grey, and Bruce counties. The main area of the African-Canadian settlement known as the Queen’s Bush Settlement was around the village of Conestoga, just north of and between Waterloo and Guelph, but also included areas around present-day Hawkesville, Elmira, Glen Allan, Wallenstein, and Galt (now Cambridge).7 Some of the region’s Black pioneers were militiamen who defended the Crown in the Rebellion of 1837, but many were either fugitives from the southern American states or free Blacks. Sophia Pooley — once owned by Joseph Brant in Brantford and Englishman Samuel Hatt in Ancaster — relocated to the Queen’s Bush when she was freed as a result of the Emancipation Act.

At its peak, as many as two thousand people of African descent resided within the Queen’s Bush. They had settled on unsurveyed Clergy Reserves, which meant that they could not purchase the land they squatted on, even though they cleared lots, started farms, put up fencing, built homes, and laid roads, along with other improvements. Several petitions were made to the Earl of Elgin, governor general of Upper Canada, who in 1850 eventually offered a deal for Black and White squatters to purchase the land they settled on, but the Black settlers could not afford the payment terms. By the late 1850s, the displaced settlers began the mass migration out of the Queen’s Bush and relocated to other African-Canadian communities. Although they were in the Queen’s Bush Settlement for a short period of time, Blacks were able to establish a strong, supportive community despite the harsh physical conditions and unfair and expensive land deals.

With the assistance of church missionaries and support from each other and Blacks in different centres, they worked hard to build a life on free soil. Several social institutions were established to meet their needs. By the mid-1840s, almost 250 students attended the two mission schools set up for African-Canadian children because they were excluded from the White common schools. Black churches of the AME, BME, Baptist, and Wesleyan denominations were also established in these villages, which were “not only religious centres for the widely dispersed populace, but also places for public meetings, social occasions, and the creation of self-help and moral improvement societies such as temperance associations.”8 In spite of many obstacles, a fair numbers of the pioneers fared well and still had reason to celebrate freedom.

Members of Queen Bush’s Black community celebrated Emancipation Day in the hamlets of Hawkesville, Elmira, and Wallenstein in Wellesley Township, Waterloo County. Some of these residents sponsored an Emancipation Day celebration in Hawkesville on Saturday, August 1, 1863, to commemorate the twenty-ninth anniversary of the abolition of slavery. Approximately twenty-five hundred visitors gathered. The Berlin Band led a street procession to the town hall where a Reverend Milner delivered a sermon. Celebrants then went on to Temperance Island in the Conestoga River near the mouths of Boomer’s and Spring creeks. A number of cooks and waiters served an elaborate dinner over three lunch shifts. It is unlikely that any alcohol was served at the event as many of the fugitive settlers in the vicinity were part of the Temperance Society of Hawkesville who denounced the consumption of rum and other spirits and were known to have “cold water” picnics on the island. Speeches were given by Reverends Downey, Milner, Lawson, and Miller.9 Presumably, the most talked about issue at this affair was the Civil War and the pending overthrow of the institution of slavery. Following the end of that war, many ex-fugitives living in Queen’s Bush returned to the United States to reunite with family or moved to other established Black communities in Canada West because of the mounting racial prejudice and the increasingly difficult conditions. However, those who did remain in Queen’s Bush continued to get together for the August holiday.

Elmira, located in Woolwich Township, was the main centre of activity for Blacks in the Queen’s Bush. They would often come into town to shop and sell goods. Emancipation Day celebrations were also hosted on the Elmira Exhibition Grounds and at the local Black church, located about six kilometres to the northwest. The last celebration in Elmira seems to have taken place in 1886. It was attended by about two hundred people who pitched tents, barbecued, and enjoyed musical entertainment provided by a band and a group singalong.10

Other nearby towns hosted Emancipation Day as well. On August 1, 1890, the fifty-seventh anniversary of the abolition of slavery was recognized in Berlin (now Kitchener), just twenty kilometres south of Elmira.

A grand barbecue was held and various games were indulged in. The principal sporting attraction was the baseball match between Hamilton and Toronto. The visitors came from Toronto chiefly, but there was quite a representation from London, Brantford, and Hamilton. This evening a grand ball and cakewalk were held in the rink.11

Another Emancipation Day observance took place in Berlin on August 2, 1894. A Black fife and a drum band led the street procession to West Side Park (now Waterloo Park) where there were many sporting events. A dance, held at the town hall in the evening, included a cakewalk contest.12

At times the Emancipation Day celebrations were held under the auspices of the local church, providing an opportunity to raise money to support community initiatives. In 1935, the African Canadians of Wallenstein had a picnic in commemoration of Emancipation Day and to fundraise for the building that was used as both a school and a church. The Black community gradually dissipated as the elders passed on and the younger people relocated to larger cities in search of better opportunities.

Simcoe County: Collingwood and Oro

During the nineteenth century people of African descent settled in several villages and hamlets in Simcoe County including Oro and Collingwood. Oro-Medonte Township, located on the western shore of Lake Simcoe northwest of Barrie and southwest of Orillia, was home to around 150 Black residents at the peak of its population. They settled on Wilberforce Road, one concession east of Penetanguishene Road, which they helped to extend northwards. These families also farmed on the plots of land they received from the government. Others went to Shanty Bay, another area in Oro Township. African-American refugees, who escaped using the Underground Railroad, comprised the majority of the citizens including those in Collingwood. Many fugitives arrived in Simcoe County by boat from such American ports as Chicago and Milwaukee, and Canadian Great Lakes ports like Sault Ste. Marie. Northern Railway operated a line of steamships in the Great Lakes and ships sailed on a regular route from Chicago and Milwaukee, up Lake Michigan, across Lake Huron, and into Georgian Bay to Collingwood and Owen Sound. It was not uncommon for fugitives to stow away on these ships.13

The town of Collingwood, founded in 1834, is located on the shore of Georgian Bay in the northwest section of Simcoe County. In the early 1900s there were an estimated 120 Blacks living mainly in the southwestern section of the town. One of the first Black settlers in Collingwood, in the 1850s, was a man named Harris who owned a tavern and hotel.14 Others include Elizabeth Piecraft who also arrived in the 1850s. She was a cook and the first caretaker of Central High School, while her husband was a labourer, the town’s bell ringer, and a fiddler on some of the passenger boats. “Dr.” Susan LeBurtis was a successful herb doctor and lived in a nice home on Sunset Point. Mrs. Bolden owned a hat shop on Hurontario Street. Abraham Sheffield worked as a pearl-ash maker and Pleasant Duval owned a barber shop and an ice cream and soda shop on Huron Street while his wife ran a dress-making business out of their home. Others were employed as house servants, whitewashers, lime-burners, bakers, plasterers, day labourers, barbers, waiters, and chefs on boats like the Armstrong and in public facilities like the North American Hotel. Joseph Cooper, a free Black and Civil War veteran, came to Collingwood in 1866 at the age of twenty-four. He worked as a labourer then opened a cork factory in 1882 where he employed eleven people. In 1904, his sons opened a contracting business to pave and repair town roads and helped to construct the old Victoria Public School, some local factories, and other buildings.15

The Sheffield family played a prominent role in Collingwood’s history. One descendant, Howard Sheffield, who passed away a few years ago, was an athlete of considerable talent and a powerful hockey player, but was barred from the major leagues because of his race. He and his niece, Carolyn Wilson, with the support of other members of the family established the Sheffield Park History and Cultural Museum, which commemorates the extensive Black history of the area.

With only a fairly small population in comparison to other places in Ontario, the Black community needed strong social supports to sustain their existence. Simcoe’ Blacks interacted at church, such as the Edgar AME Church, established in 1848 under the leadership of Reverend Richard Sorrick, or the BME Church, which met in people’s homes until a building was constructed on Seventh Street in 1871. In particular, they gathered at the home of Pleasant and Mariah Jane Duval on Sixth Street. Pleasant Duval is said (according to family oral history) to have walked from New Orleans to Collingwood. The Duval home was described as the social centre for Blacks in Collingwood, Owen Sound, and surrounding region. Parties, picnics, and other occasions were held there. The Blacks of the area also came together for the August First holiday.

Numerous celebrations were held in Simcoe County, usually spread over two days so that celebrants could support events and spend time with friends in Owen Sound. These affairs would have been attended by members of the Collingwood community and guests from surrounding centres.

Members of Oro’s African-Canadian community also held many commemorations. A local White author wrote an account of the celebration from personal recollection:

One of these great occasions is in the beginning of the long hot days in August when Darkey Hollow empties its brilliantly altered population into the Maple Grove above the Wanda Falls where they hold a monster picnic, commemorating their fathers’ emancipation from slavery. Then, perhaps, for the first time in the year we feel in touch with our less fortunate neighbours. There is nothing like the mention of slavery to touch the heart of one who revels in the glorious freedom of the Land of Maple. Thoughts of their great day of darkness come back on this day of their great rejoicing, to give us sympathy and to keep our hearts warm from our downtrodden brethren during the coming trials of winter. But the first of August under the maples, with Joshua DeForest playing the fiddle and Miss Lavinia Lodice Smith in all glory of a flaming blue gown and white veil …16

They conducted street processions on Wilberforce Road, marching together, playing small instruments, and singing spirituals and plantation songs.

While the tone of this description is very patronizing, it is useful for three purposes. One, it gives details on how Blacks in Oro observed Emancipation Day. Secondly, it reflects the attitude of some White Canadians at that time, and third it speaks to the tenacity of the fugitive settlers who continued celebrating and rejoicing their freedom, even though they experienced hardships in their new home, struggling with poor farmland and harsh winters.

According to another account, there was a regular soccer game between Black and White players from local teams that attracted a large number of spectators from near and far. “The negroes were skilled at hitting the ball with their heads and sending it great distances. Their weak spots were their shins, a fact that their opponents kept in mind.”17 In a poem written by W.R Best, another White resident of Oro, he says: “Emancipation day they had a glorious time….”18 From these pieces of literature, the conclusion can be drawn that August First commemorations were an important social institution in the county.

When John Nettleton19 arrived in Collingwood with his family in 1857, he recorded his observations on the early town:

There was also quite an extensive colored settlement between 6th and 7th streets, near Walnut street. Being nearly all escaped slaves from the United States they celebrated the British Emancipation Day on the 1st of August by a picnic and dance, under the big elm trees on Third Street. Mayor McWatt, Adam Dudgeon and Peter Ferguson delivered orations to them about the glories and freedom of the British Empire and the citizens used to join them in the evening in dancing.20

Whites and Blacks celebrated together, as noted by Nettleton and by the following description in an article dated July 30, 1862, from a slightly torn copy of The Spirit of the Age, a local Barrie newspaper:

being the twenty-eighth anniversary … Emancipation by England of the … slaves is to be kept by the … people of this county with more…. [ordinary] signs of rejoicing and thankfulness. They are to meet at Barrie and among the proceedings of the day have arranged for a religious service, at the conclusion of which a sermon will be delivered by the Rev. Mr. Morgan. In the evening the party will dine together, and afterwards hold a soiree, when several able speakers will address the meeting. The rejoicings are not to be confined to the coloured people, but all who feel friendly towards them are desired to join their party. We trust the interesting proceedings will pass off successfully.21

By the 1860s interracial groups of Simcoe County residents were meeting at Sunset Point Park on Georgian Bay, having followed a parade through Collingwood to the waterside site. Joined by Blacks from Owen Sound, who walked about sixty kilometres to get there, they listened to speeches and picnicked for the afternoon. The evening program consisted of a lively dance or a festive banquet.22

Eventually, the number of African-Canadians living in Simcoe County gradually declined when some faithful Oro followers of Reverend Sorrick moved to Hamilton in the 1840s after he accepted a position there. In the 1850s and 1860s, some who were living in more rural areas relocated in Collingwood, and Emancipation Day festivities were kept alive well into the 1900s. Just at the turn of the century “Colored people from all parts of the county gathered at Nottawasaga River … to celebrate Emancipation Day” where they enjoyed the day at the beach.23

In the mid-twentieth century, some people in Simcoe County got together at Sunset Point for a picnic, games, and social interaction. The older kids who were good swimmers would go up the road to swim at Black Rock and the younger ones played on the swings or played baseball. First of August festivities were usually combined with the Sunday school picnic in the 1950s, then gradually faded out as the younger generation moved away.

After that celebrants went up to Owen Sound. The two BME churches, the Masonic and Eastern Stars, and Black fraternal orders, tended to join together for events then, just as they do today, to strengthen the numbers attending. This shared event approach was a natural evolution as everyone was related in one way or another, and Collingwood had a much smaller Black population. Those adults who really wanted to party usually went to a house party in the evening.24 Alternatively some of the small number of local Blacks would travel to other celebrations like the colossal ones held in Windsor or St. Catharines.