The sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality.

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream,” 1963.

The earliest Black pioneers of Nova Scotia (at that time part of Acadia) and other parts of the Maritimes were enslaved by French, and later by British, colonists. As the practice of slavery declined, Black pioneers (the free Blacks who worked for the British military during the American Revolution) relocated to Nova Scotia. They were followed by Black refugees, the escaped slaves who helped to defend Britain during the War of 1812. For their service, almost two thousand Black refugees migrated to Nova Scotia between and 1815 and 1834 to live on free soil in areas like Shelburne, Birchtown, Hammond’s Plains, Preston, Digby, Yarmouth, and Halifax, including Africville.1 These families linked themselves to their African kinsmen throughout Nova Scotia in celebrating their shared liberation from enslavement and their desire to build a new life and rejoiced through August First commemorations.

From 1846 to 1867 Emancipation Day celebrations in Halifax were organized by a benevolent society called the African Abolition Society(AAS). Started by Baptist minister Richard Preston2 in 1846, the mixed group of former American slaves, descendants of Canadian slaves, and free Blacks “dedicated itself to the eradication of an institution that had been illegal in the British Empire since 1834…,”3 but also aimed to improve the lives of Black residents through charity, education, religion, and community development. They provided help to fugitives during the peak period of their arrival between the 1840s and the 1850s, invited speakers to lecture on African history, slavery, and the impact of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. They also hosted other community events including celebrations of the anniversary of the abolition of British slavery.

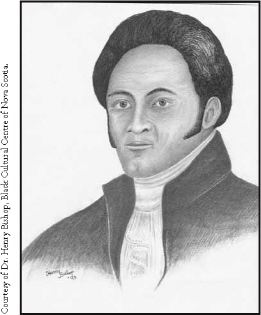

Reverend Richard Preston was an anti-slavery activist and community leader. He established eleven Baptist churches in Nova Scotia and organized the African Baptist Association of Nova Scotia.

Amani Whitfield in Blacks on the Border describes the AAS as being run almost exclusively by former slaves. In a move to solidify autonomy and minimize the influence of local Whites, the organization barred them from joining the society’s executive committee so that they could not participate in any decision-making regarding internal policies or practices. However, the AAS did invite Whites to attend AAS public lectures and some meetings.4

Emancipation Day was a way for the new arrivals to establish a connection with other people of African origin across the British Empire and to see themselves as subjects of the Crown and free people. The festivities also served to focus the attention of Blacks living in Halifax on abolition in the southern United States as well as on the racial discrimination they faced in their daily lives. Most of them faced residential segregation as their communities were intentionally and completely secluded from white settlements, as determined by the way land grants were issued. The plots they received were on poor, rocky land, which limited their farming opportunities and adversely affected their quality of life.

Additionally, common schools were separate by law in their isolated communities and since Black schools did not receive sufficient funding, primarily White church missionaries and White abolitionists delivered the education. Another instance of letting Blacks know they were not necessarily welcome in Nova Scotia was the passing of “An Act to Prevent the Clandestine Landing of Liberated Slaves … from Vessels arriving in the Province” in 1833, enacted by a local government apprehensive of a potential flood of fugitive slaves pouring into Nova Scotia once the Emancipation Act took effect. Enforcement focused on ships coming into the harbours that might be carrying refugees. Any Black refugees found on these ships were to be denied entry to Nova Scotia. The captain of the ship would be fined if escapees were found on his vessel or would have to give surety for the ones he knew of and would vouch for. This legislation was in effect for two years, after which the assembly attempted to renew the bill. However, the British Parliament prohibited any renewal and deemed the bill to be discriminatory, citing that it countered the intention of the Emancipation Act as people of African origin were now entitled to the same rights and privileges as any British subject.5

The refugees, the Loyalists, and their descendants generally accepted their conditional freedom and sometimes poor quality of life as better than being chattel property. As a female refugee pointed out, “I’ll live on ’taters and salt and help fight myself till I die, before I’ll be a slave again.”6 However, they actively pursued the ideal of equal citizenship and the full democratic rights entitled to them as British subjects and worked to improve the situation for themselves and future generations.

August First commemorations were representative of this dilemma. On the one hand, Blacks in Halifax expressed gratefulness for the liberty on British soil, however limited, yet they employed this public medium to rally for racial equality. Also the day was one of the few times each year for African Canadians who lived near and far to socialize. To ensure a sizable turnout and to make a public request for their brothers and sisters, the AAS placed ads in mainstream newspapers such as the Novascotian and the British Colonist to encourage White employers to give their workers of African descent the day off. The occasion usually consisted of a procession through Halifax, followed by speeches from former slaves and government dignitaries, and concluding with picnics and other festivities in the evening.

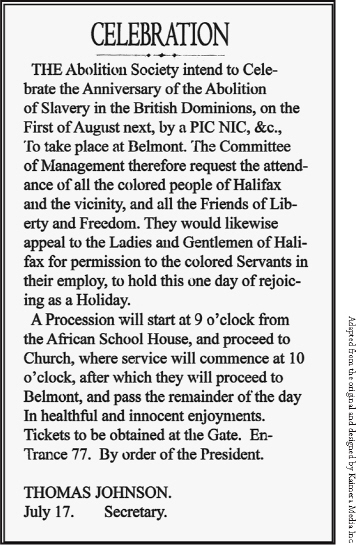

A reproduction of an advertisement that ran in the British Colonist (Halifax) on July 19, 1851, requesting that White employers give Black employees the day off to commemorate Emancipation Day.

In 1847, the African Abolition Society hosted their second annual Emancipation Day celebration. Led by a military band, those assembled paraded through the streets of Halifax carrying banners praising “freedom and British liberty.” They marched to the Government House7 at Barrington and Bishop Streets, just south of Spring Garden Road, to listen to a schedule of addresses. Members of “the Society departed to the festive grove at the North Farm where the remainder of the day was spent in the usual pleasures.”8 The North Farm property belonged to the governor and was situated at the north end of Gottingen Street where Devonshire Avenue crosses today.9

The 1850 celebration that recognized the sixteenth anniversary included a procession led by the band of the flagship Wellesley. They marched about one kilometre northwest from the African School House10 at the corner of Gerrish and Maynard Streets to the African Baptist Chapel on Cornwallis Street. A moving sermon was most likely delivered by Reverend Preston, then the gatherers continued to Belmont House, south of Oakland Road and west of the southward extension of Robie Street. At that time it was owned by John Howe Jr., half brother of Joseph Howe. He commonly offered the grounds of Belmont for various public and private events. Here they were treated to more speeches, refreshments, and entertainment. The increasingly interracial crowd included Joseph Howe, provincial secretary, former editor of the Novascotian, and father of confederation, who evidently had a pleasurable time at Belmont:

The Hon. Provincial Secretary was driven to the ground in a cab, seated on the knee of one of the coloured men … We have no disposition whatever to cast a slight upon the members of the Abolition Society, but we do not think it exactly becoming the dignity of the chief officer of the Province to embrace them or to sit upon their knees … Oh Joseph, thy career has indeed been glorious, and thy children will think upon their father with pride!”11

The thirteen toasts drunk at the event reflected the racial and global awareness of the established Black community in Halifax and their loyalty to Canada. The first salute memorialized “Africa, the land of our Forefathers,” then the Queen, Prince Albert, local government officials, and church leaders. The ninth acknowledgement was to the AAS, “may she never fail in promoting the cause of her poor and oppressed people, from every nation beneath the Sun” and the following thanks was extended to “The Printers, who have been so kind and liberal towards the cause of Emancipation.”12 As the newspaper was the mass media of that time, it was important to maintain a relationship with the editors and the printers in order to have access to a large audience. Mainstream newspapers across Canada reported on Emancipation Day that took place in their cities and towns as well as in other jurisdictions.

In 1852, Emancipation Day was observed on August 3rd with a street procession to the African Baptist church to hear a service, most likely by Reverend Preston. The band of the 97th regiment led the large numbers of gatherers through the main streets of Halifax, and then continued onward to the Belmont estate for various festivities. On the way back to the city, the band played the tune of “Get Out the Way Old Dan Tucker,” more than likely a popular Emancipation version of the song with anti-slavery lyrics (see Appendix B). The 1853 observances took place at Melville Island and were attended by lots of people. Melville Island13 is located five kilometres west of Halifax, at the head of the northwest arm of Halifax Harbour.

The African Abolition Society hosted a private dinner in 1855 to recognize Emancipation Day where forty society members and guests attended to partake of a shared meal. At the events during the 1850s, at least fourteen toasts were raised each year. The salutations always covered the globe from Africa, to Britain, the West Indies, and North America. The proposals reveal the global perspective they held and the many components of their African-Canadian identity. Homage was always paid to the African’s land of origin, gratitude to Britain for discontinuing an inhumane practice, for opportunities in Canada, strong opposition against American slavery, and the promise for a brighter future.14

One month after Confederation in 1867, another large group assembled and paraded through the main streets of Halifax out to the shores of the Bedford Basin to enjoy a bountiful picnic. Unfortunately, the day was marred by a racially motivated attack. The participants returning to the city core were assaulted by a crowd of White thugs that could only be quelled by police reinforcement. Consequently, the evening soiree at the Mason Hall on Barrington Street was cancelled.15 This was not only a physical clash, it was also a conflict of ideals that simmered in all parts of Canada. While native-born and immigrant African Canadians felt that the union of the provinces of the nation would further secure their citizenship and that they would be finally be embraced as contributing members of society, a segment of the White Canadian population believed that there was no place for them in the new Dominion. The sentiment of people of African descent not being true “Canadians” lingers today in the trite question, “Where are you from?”16

Shortly after 1867 Emancipation Day was commemorated chiefly with small group picnics. Why did the grand public affairs end with the confederation of the Canadian provinces? It is likely some American residents repatriated to the United States, thus reducing the number of Blacks in the vicinity. As such, with the end of American slavery there was no longer the pressing issue of emancipation. Perhaps many assumed that the formation of the Dominion of Canada further guaranteed their rights and place in Canadian society, thus rendering the civic demonstrations unnecessary for the purpose of mobilizing for political and social causes.

African-Canadian settlements in Guysborough County have also held Emancipation Day commemorations. Through to the 1950s, New Road, a Black neighbourhood now known as North Preston, held their Emancipation Day celebrations in isolation from observances in other nearby Black communities in Cole Harbour and Halifax. In 1856 Richard Preston established the Second Baptist Church in the New Road vicinity.17 As chief organizer of August First observances in Halifax and minister of eleven Black Baptist churches in Nova Scotia, it is likely that he coordinated events in other locations or planned joint commemorations.

Nova Scotia marked the 175th anniversary of the abolition of slavery by the British parliament with an emancipation celebration called Black Freedom 175. Organized by the Amistad Freedom Society of Nova Scotia, the main highlight of the week-long festival at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax was the visit of the schooner Amistad, a replica of the famed ship that was seized by the United States Navy for illegal slave trading. Since 1807 by British law and 1808 by American legislation, the slave trading across the Atlantic had been prohibited. One of the captives, named Cinque, led a revolt and all were charged with mutiny and murder. In a historic court decision by the United States Supreme Court in 1841, it was determined that the native Africans were kidnapped and not Cuban-born slaves and were recognized as never being legal property, but were human beings with human rights. They were subsequently returned to Africa through the assistance of abolitionists of the Amistad Committee. The decision also struck out against ongoing American slavery by marginally recognizing the human rights of Blacks.

The event also consisted of a welcome gala, performances by numerous local and international musicians, drumming, poetry, speeches, public tours of the replica tall ship, and activities for youth, including a sail and workshops to build leadership skills, explore diversity, and appreciate freedom. Natal Day, the official birthday of the communities of Halifax and Dartmouth is now the recognized August First holiday.

Enslaved Africans first settled in the present day Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, historically known as Acadia. Up until the end of the eighteenth century when the practice of slavery dwindled, a few hundred enslaved Africans lived in numerous New Brunswick Loyalist settlements including Otnabog, Carleton, Gagetown, and Fredericton. The number of Blacks increased during the Revolutionary War when escaped slaves who were granted freedom by British soldiers settled in Loch Lomond. They were joined by Black pioneers; free Blacks employed by the British army during the American Revolution. A large number of these Black Loyalists created a settlement at Elm Hill. Another wave of African-American immigrants entered New Brunswick in 1815 when nearly four hundred Black refugees of the War of 1812 arrived. Some would receive eight- to twenty-hectare land grants in several towns, including an area just east of Loch Lomond where they established a Black community called Willow Grove, about ten kilometres northeast of Saint John (now part of East Saint John). Yet more would come to New Brunswick, most fleeing the United States from the reach of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

The experiences of African-Canadians in New Brunswick were similar to those of their counterparts in other Maritime provinces. Although they were no longer enslaved on either side of the border, their freedom was restricted by local and provincial governments. Some were denied the land grants they were promised by Crown officials, while those who did receive land grants were often given property in isolated, poor, rocky, or marshland areas. The lots were often smaller than promised and smaller than the ones given to White Loyalists. Furthermore, most did not receive sufficient aid to assist in settling in to their new homes. When the City of Saint John incorporated on April 30, 1785,18 its charter placed several restrictions specifically on the growing Black community. People of African origin could not become free men19 and were prohibited from practising a trade or selling goods in the city, barred from fishing at Saint John Harbour, and could not reside within the city limits unless employed as a servant or a labourer. These stipulations, which remained city law until they were removed in 1870, severely restricted not only the development of the African-Canadian community in the area surrounding Saint John, but limited personal development as well; the separate schools that their children attended were inadequate and they also had to fight racial prejudice in its many forms. In 1830 a Black man and several Black women were victims of a racially motivated physical attack.

In spite of the obstacles brought about by racism from government authorities and some of their White neighbours, many Blacks remained in New Brunswick. These people included African Canadians of multi-generations and recent colonists who were determined to live in freedom, albeit restricted, and to contribute to their communities. Robert Whetsel, a fugitive from American slavery, settled in Saint John around 1852. He was originally from Virginia, but had escaped to Chicago and eventually made his way to Saint John. Whetsel was an entrepreneur: first establishing a barbershop, followed by an oyster saloon, then a successful ice business, the only one of its kind. Whetsel was very active in the Black community and highly respected by both Blacks and Whites. He was described in his obituary as one of Saint John’s “representative colored citizens.”20 Therefore, it is likely that Whetsel played a role in or attended a celebration of the nineteenth anniversary of the end of British slavery. A tea was hosted at St. Stephen’s Hall at the corner of King Square and Charlotte Street, followed by speeches “by some of our leading philanthropic and public men.”21

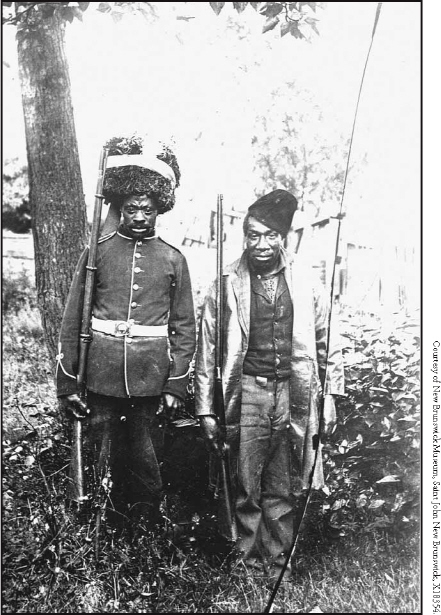

Another fugitive slave who did well in New Brunswick was Cornelius Sparrow, who made the difficult journey from Virginia to Saint John in 1851. After working as a labourer for ten years, Sparrow opened the first of three successful business ventures, including two restaurants and a unisex hair salon. Black men like Dan Taylor and Alex Diggs continued to volunteer in militias in Saint John and Fredericton to defend their country and demonstrate their loyalty to the Crown, even though they were forced to lead segregated lives. They enlisted in the all-Black company of the York County Militia until 1849, the African Staff Company that had been organized and attached to the Saint John Regiment in 1813, and in the all-Black Pioneer 104th Regiment, which had formed in 1814. Black men from New Brunswick served in the Construction Battalion Number Two in the First World War, and in regular integrated military forces.22

Militiamen Dan Taylor and Alex Diggs attended the Loch Lomond Fair circa 1900.

African Canadians in New Brunswick, as in other communities, established churches such as the St. Philip’s AME Church in 1859 in Saint John and the Willow Grove Baptist Church for worship and fellowship. Blacks celebrated Emancipation Day together despite their limited citizenship rights and the racial discrimination they faced. They were still thankful for what they had, but were determined for themselves and their successors to live a freer life on British soil and for their brethren in America to be released from bondage. A brief article in the Novascotian on August 15, 1859, reported that:

The colored population of Saint John, New Brunswick, celebrated the anniversary of the emancipation of the slaves of the British West Indies on the 1st inst. At a meeting held at the Mechanics’ Institute in that city, capital speeches, interspersed with songs, glees, etc., are said to have been delivered.23

In 1863, as the Civil War swept across the United States, African Canadians in New Brunswick observed Emancipation Day. A local newspaper reported that about five hundred people congregated in Saint John at Mr. Smith’s building in the evening. Robert Whetsel chaired the meeting and delivered an address, followed by an African-American guest from Boston named Francis. It was an interracial gathering with several members of the Irish community attending and speaking, such as Timothy Warren Anglin, founder of the Saint John Weekly Freeman newspaper, and a few other community leaders in attendance. The speakers extended gratitude to Britain, expressed the desire for victory over the South in the Civil War, and deliverance from bondage.

Entertainment included music by the City Band and a performance by Mr. Patterson, who “sung a song on Emancipation to the air of ‘Old Dan 24 The tune “Get Off the Track!” appears to have been quite popular Tucker.’”among African Canadians celebrating August First in the Maritimes. The author of the lyrics predicted the end of American slavery would come at the end of the Civil War: “Emancipation soon will bless our happy nation.”25 In the 1860s, the folk music by Black and White abolitionists carried a strong political message against the institution of slavery. It instructed enslaved Africans and all friends of liberty to jump aboard the freedom train: “Ho! The car Emancipation rides majestic thro’ our nation.”26

As discussed in the section about Nova Scotia, the number of African Canadians on the east coast lessened with the victory of the Union Army in the Civil War. Many of the refugees returned home to the United States and with the abolition of slavery Emancipation Day gatherings declined and eventually ceased. Today the first of August is a provincial holiday called New Brunswick Day.