The most rewarding freedom is freedom of the mind.

— Amy Garvey, Garvey and Garveyism, 1963.

The onset of the twenty-first century triggered a revival in the observance of Emancipation Day in locations that previously celebrated the holiday. From the 1990s onward, the celebrations have experienced a move to new venues and a change in format to attract a wide array of supporters. Celebrations in Toronto were revived in 1997 by the Ontario Black History Society, and in Windsor in 2008 by the Windsor Council of Elders and Emancipation Planning Committee with the support of several other community organizations and the City of Windsor. Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site in Dresden began commemorations in 2005. Owen Sound observances have persisted throughout the years, but have been restructured to retain relevancy for ongoing participants and to attract new visitors. A particular element is the renewed emphasis on education with a specific interest in the recognition of both local and general African-Canadian history. The current organizers of both Owen Sound and Windsor events have utilized a weekend-long festival format packed with many activities designed to draw huge audiences. In Quebec, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Montreal hosted an Emancipation Day event in 2009.

Several reasons can be attributed to the resurgence of Emancipation Day observances. One is the surge in popularity of genealogy. The research of one’s ancestors is attracting more and more African Canadians, and through familial investigation descendants of early Black pioneers have discovered important facts about their forebearers and about the social interactions of early Canadians. Secondly, there is a new cohort of people, White and Black, intrigued by the history of African Canadians and their contributions to the building of this nation. Canada has a sizeable population of Black citizens, but very few know about the nation’s rich African heritage. Many are trying to understand how early Black Canadians dealt with such pressing issues as promoting education for their community, facing pervasive racism, encouraging integration, and creating an identity for themselves. All are issues that continue to be problematic for people of African descent living in this country, along with the need to engage in matters that affect Africans throughout the Diaspora. Many seek to draw from past knowledge and strength to solve these problems, and Emancipation Day has played an integral role in the past in tackling these issues.

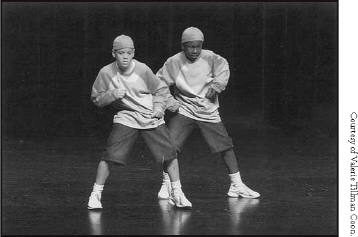

Strictly Rhythm Hip Hop dance performers from Guelph on stage at the Emancipation Festival in Owen Sound in 2007.

Emancipation Day has come full circle, once again being employed to educate and mobilize new generations. There has been a resurgence in the “freedom movement” both personal and social in an attempt to liberate our society and ourselves from modern forms of social confinement — mental enslavement, materialism, commercialism, and violence.

Underground Railroad Cyclists at the Owen Sound Emancipation Day Celebration, 2007. The Adventure Cycling Association, in partnership with the University of Pittsburgh Center for Minority Health, retraced one of the escape routes from Mobile, Alabama, to Owen Sound following the “Drinking Gourd,” the Big Dipper Constellation. Another tour called the Underground Railroad Celebration Ride cycled from Buffalo, New York, to Owen Sound.

Once again, advocates are seeking legal recognition of Emancipation Day. A provincial bill was passed into law in 2008 to officially recognize the first of August as Emancipation Day in Ontario. The Ontario Black History Society had petitioned different members of the provincial parliament and the premier of Ontario to implement a legal acknowledgement of Canada’s history of enslavement and its role as a haven for fugitive American slaves.1 There is also a push to internationalize the legal recognition of Emancipation Day by the National Joint Action Committee of Trinidad and Tobago in all territories of the former British Empire in the Caribbean, North America, and Africa. Emancipation Day is relevant to the continent of Africa in recognition of the loss of millions of people that ravaged the economic, political, and social development of villages, kingdoms, and nations in Africa, and because of the many Africans enslaved on the continent by the British in their possessions such as South Africa.

Coincidentally, in Ontario, Emancipation Day coincides with the August 1st Civic Holiday that honours Lieutenant John Graves Simcoe, who was instrumental in setting the wheels in motion to end slavery in Upper Canada. Individuals and community groups have suggested the two observances be officially merged. Evelyn Myrie, writing in the Hamilton Spectator, suggests that, “The idea of formally combining the Lord Simcoe Day with Emancipation Day should be given some consideration” because Simcoe’s efforts “gave Upper Canada the distinction of being the first jurisdiction in the British colony to pass an anti-slavery act.”2 Joining the two observances would be a powerful educational tool for highlighting knowledge about Canadian slavery and the abolition movement. At commemorations at the Griffin House and Fieldcote Memorial Park and Museum in Ancaster, which began in 2002, Anne Jarvis, the historical interpreter there, said: “We are open on the holiday Monday so the Civic holiday in August seemed the obvious date for the recognition as it is the nearest date to Emancipation Day.”3

How can Emancipation Day remain pertinent to African Canadians and the wider society in the twenty-first century? The nature of commemorations must stay true to its roots while incorporating innovative means of retaining and capturing the interest of its audience. Current approaches used by the organizations in localities mentioned, in an effort to be relevant to today’s adult and youth, blend current forms of entertainment and urban culture such as cycling tours, basketball tournaments, walk-a-thons, hip-hop dance competitions, and art shows with traditional ones like storytelling, presentations, picnics, and parties. One suggestion is that plans to restore the celebrations should go one step further by creating a “commemoration circuit” whereby each of the established locations and any other sites planning to revitalize August First as recognition of the abolition of slavery might alternate with nearby communities to host larger-scale events.

Yet another approach could involve a promotional initiative linking existing Emancipation Day celebrations in the manner of the Underground Railroad African-Canadian Heritage Tours, which are growing in popularity. By partnering in this manner, long-established annual events — such as those at Owen Sound, Ontario, and newer smaller celebrations elsewhere — could, by working together, bring about greatly increased appreciation of the Black experience and the contributions of African Canadians to Canada’s rich heritage.

Moving forward with co-operative planning would enable people to learn more about their province and country and its diversity, which in turn would assist in the process of the development of a Canadian identity for descendants of native-born African Canadians and for people like myself who are African Canadians with immigrant parents. It can encourage them to reclaim — and claim — their heritage and their nation. For new citizens it can foster an understanding of the people who came before them. Emancipation Day will continue to adapt to the people and the needs of Canada until Canada has achieved complete equality for all of its citizens.

Whatever new directions lay ahead, there is little doubt but that Emancipation Day celebrations will continue as an important cultural tradition with significance for all Canadians.