Rakovník, March 1938

IT WAS DIFICULT AT TIMES for Hana and Karl to reconcile what was happening outside Czechoslovakia’s borders with the daily life they lived in Rakovník. School continued as if there were no difficulties elsewhere. They were in different grades and attended separate public high schools, both of which were known for their high academic standards and strict discipline. Hana and Karl learned Latin, French, and German, along with mathematics, history, geography, and other subjects. Their German teacher did mysteriously disappear at one point, and no one seemed to know where he had gone or why. But Leila continued to speak German to the children, as she had been doing for years, and they became more and more fluent in her native language.

And then, events in Germany took a new and terrifying turn. It was a particularly cold and blustery evening in March 1938 when Hana and Karl returned home from the cinema. As they entered the house, they were still in an animated discussion about the American film actress, Jeanette MacDonald. Their cheeks were flushed from the damp wind that had blown through the streets, whipping leaves and debris up into their faces. Hana unwound her woolen scarf and cap and shook her curly red hair free. Lord and Dolinka were there to greet their masters, barking and jumping up and down enthusiastically. But when Karl and Hana walked into the salon, the stone faces of their parents instantly quieted them and their pets. At first, no one spoke. The only noise in the room was the sound of people cheering from the radio behind the heads of their parents. And the voice that shrieked loudest of all was unmistakably that of Adolf Hitler.

“What’s going on?” Karl began. The looks on the faces of his parents alarmed him.

“Shh!” his father barked, further disquieting Karl.

This was not the first time he had heard Hitler’s voice on the radio. On each previous occasion, the members of the household would stop whatever they were doing, nearly hypnotized by this man’s fanatical pronouncements, each one ending predictably with an anti-Semitic tirade.

“They’ve taken over Austria.” When his mother finally spoke, there was both rage and alarm in her shaky voice. “The Nazis marched into Vienna today. No one stopped them,” she added bitterly.

“Listen to the crowd cheering,” her husband added. “No one stopped them because they welcomed it. That maniac is being treated like a hero in Vienna.”

Hitler’s voice rose from the radio as he declared, “I have in the course of my political struggle won much love from my people, but when I crossed the former frontier, there met me such a stream of love as I have never experienced. Not as tyrants have we come, but as liberators.”1 And sure enough, the voices of the masses shouted in return, “Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!”

“I knew this would happen,” Marie stated somberly. She had the same stricken look she had worn the day the house had been vandalized.

In the weeks to come, she continued to hold fast to her belief that it was only a matter of time before Czech Jews would be targeted by Hitler. The details of the Anschluss were particularly shocking and depressing for Victor, who continued to insist that the family was still safe while declaring his contempt for the international events. But eventually even he had to acknowledge that the situation was deteriorating. Under pressure from his wife, Victor also began to buy up foreign currency to safeguard the family’s funds.

George Popper’s family came for dinner several weeks later, but food took second place to the animated conversation between George’s parents and Karl’s.

“I’ve been telling Victor for months now that we should ready ourselves in case we need to leave here,” Marie declared. “The occupation of Austria is just the beginning of Hitler’s crusade. But my husband doesn’t see things my way.”

“Don’t be silly,” said Mr. Popper gently. “We aren’t in danger here. Great Britain will always guarantee our independence and integrity against any forceful aggression from outside.” George’s father sounded exactly like his own, Karl thought. Zigmund Popper was a gregarious man who believed in his family’s assimilation into the country as much as Victor did.

“That’s what I keep telling Marie, but she doesn’t seem to want to believe me,” Victor said. “She seems bent on leaving Rakovník, whereas I believe we are safest staying right here.”

Also seated at the table was Rita Popper, George’s sister and Hana’s best friend. Rita was a pretty girl with straight brown hair. Her serious disposition was an interesting match for Hana’s usual sense of fun. But both girls were silent that night, seemingly glued to the conversation.

“I saw one of our neighbors the other day, and she told me that her children have left for Palestine,” said Mrs. Popper. “That poor woman. She seemed so bereft without them. Can you imagine separating your family like that?” Irena Popper was quieter than her husband in these social situations, but in her work, she was a force to be reckoned with. She ran the clothing business that she owned with her husband virtually single-handedly.

“Never!” declared Marie. “If we must go, we’ll go together.”

“Let me remind you that those children left for religious reasons,” Victor replied. “They are the most observant family in town and their children wanted to pursue a more Jewish life in Palestine. That’s not the case for any of us.”

“I agree,” added Mr. Popper. “We’re Czechs first and Czechs we will always be. There will be no restrictions on us here in our homeland.”

By now Karl had tired of this conversation. He excused himself from the table, motioned George to follow him, and the two boys made their way up onto the roof of the house where they could have their own discussion away from the adults.

“They say that we might be barred from attending school here,” Karl said, pulling his jacket tighter around his body and flipping the collar up to protect his neck. The night air was brisk, though the sky was clear and overflowing with stars. “Can you imagine if they close our school to Jews?”

George pushed his glasses up on his nose and nodded. He was a tall, stout young man, with a bookwormish look that matched his exceptional intellect. “I’ll be leaving at the end of this term to go to university in Prague. I think that, with everything happening in Austria, it’ll be a relief to get out of Rakovník and into the big city. It’s killing my mother to see me go,” he added. “But at least it’s close by. I’m sure I’ll be back frequently.”

“What about the rest of your family?” Karl asked.

“They’ll stay here,” replied George.

Karl nodded and said nothing. He knew he would miss his good friend – and he feared that when George left and Karl became the only Jewish student at the school, he would become even more of a target.

The ensuing days were uneventful. Everyone returned to their work or business, putting the events in Austria into the background, lulled into a false sense of confidence that no news was a sign of stability. And then one day Hana returned home from school anxious and distracted. Without pausing to say hello to her mother, she stormed up the staircase and pounded on Karl’s bedroom door.

“What is it?” he asked as soon as he saw her face.

“Listen,” she replied, dead serious. “I have to tell you what happened on the way home today.”

She had been riding her bicycle home from school as she often did. The streets were quiet. “I was passing the photography shop and I saw that there were lots of pictures displayed in the store window. So I stopped to look at them.”

The previous year, Hana, Karl, and their parents had gone to this studio for a family portrait. It had taken forever for the photographer to compose the family and snap his picture, long tedious hours during which Karl and Hana had wished they were outdoors with their friends, or reading a book, anything rather than being forced to primp and pose for a camera lens. But everyone had to admit that the final result was well worth the effort. The family portrait that hung in the living room was attractive and expertly done.

“I was thinking about our portrait and I was curious to see the other family photographs that the shopkeeper had lined up in the window.” Hana paced in Karl’s room as she recounted her story. “And that’s when I saw it.”

In the center of this gallery, proudly displayed, was one large framed picture that made Hana’s blood run cold. It was an SS officer, no one that Hana recognized, but his uniform was unmistakable – particularly the swastika on his armband that radiated from the portrait.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes,” continued Hana. “He was smiling in the picture, but all I saw was the Nazi insignia on his arm. I just glared at his face.” She stopped and faced her brother. “What are they doing proudly displaying this picture of a Nazi? Don’t they know what he is?”

“What did you do?” asked Karl. He felt his own blood boil.

Hana gazed calmly at her brother. “I looked around her to see if anyone was close by. Then I looked back at the photo of the SS officer and I spat directly at the shop window.” Hana finished her story. “That’s what I did!”

Karl returned her gaze evenly and nodded his approval. “If I had been there, I would have done exactly the same thing, Hana,” he said. Meanwhile, in the Reiser household, more plans were being developed that would provide some safety for its members. Father Ferdinand Hrouda was a sympathetic priest in town. Victor knew this when he approached him to arrange for the priest to perform a Catholic marriage ceremony for Marie and himself. Notwithstanding his ongoing belief that Czech Jews were safe, Victor felt that Catholic marriage papers might provide some added protection in the event that they were targeted in any way. Father Hrouda obliged. He agreed to witness Victor and Marie’s vows in a private ceremony. He signed the marriage certificate and provided the family with false baptismal certificates. Armed with these papers, Victor and Marie returned home to show their children.

“I always wanted to show your mother how much I loved her,” teased Victor. “I never imagined I would do it in a Catholic service. What would our rabbi think of this?”

It’s so easy for father to joke, thought Karl. But he wondered if these papers would really do anything to protect the family. Were they being naive to think that a piece of paper would separate them from other Jewish families in Rakovník if the Nazis came looking? Sometimes, Karl dismissed these negative thoughts and, like his father, held fast to his belief that all would be well. But these moments of calm were followed by moments of utter anxiety. More and more, he was beginning to fear that Jewish identity was not merely about religious observance. He could no more divorce himself from his Jewish heritage than he could deny his red hair and freckles. His father could pretend that being Jewish was of lesser importance. He could proclaim their Czech nationalism; he could try to hide his family behind Catholic documents. But, at the end of the day, they were being targeted for their roots – their genetics – and theirs were clearly Jewish.

Mother was not nearly as good-humored as Father. “There’s one more thing that I want you to do,” she insisted. “That villa in Prague that is owned by our friends, the Zelenkas – I want you to rent the downstairs flat from them.” Victor looked puzzled. “It will be a place to go if we need it,” she continued. “It will be easier for us to hide our identities in Prague amongst the masses.”

Even with the Catholic papers in their possession, Marie’s mind was still focused on leaving Rakovník. She had not abandoned the plan of getting out of the country, but Prague would be the first step in her exit strategy.

Victor shrugged. “What if people suspect that we are trying to run away?”

“Your business takes you to Prague every week,” Marie replied quickly. It was true that Victor traveled to the capital city every Tuesday to sell his grain crops on the commodity exchange. “If anyone asks, we’ll say that you are tired of staying in hotels,” she continued, detailing an explanation that sounded as if it was already well rehearsed. “People will understand that a flat is a more comfortable place to stay.”

Victor finally relented and, with his consent, it appeared as if the family might actually abandon their home and flee to a safer place.

No one in Karl’s hometown suspected that his family was fashioning an escape plan. They shared no information with friends or other family members. Marie in particular did not want to implicate anyone else in their arrangements; she did not trust that anyone would be able to keep their plans a secret. As for Karl, he said nothing to any of his classmates. No one in any case would have cared about the intentions of the only Jewish boy in class. Besides, this was the septima, the last year of high school, and Karl’s matura, the final exams, were fast approaching. They would be tough, a long set of oral and written tests that would determine his readiness for university. This should have been the most important time in Karl’s academic life. He should have been solely focused on his studies, day and night, analyzing mathematical problems, memorizing historical dates, conjugating verbs in Latin and French. But Karl was thinking of none of this. The unrest that had begun in Austria was finally and inevitably moving inside the borders of Czechoslovakia.

The three million German-speaking citizens living in Sudetenland continued to claim that they were oppressed under the control of the Czech government. The reports that appeared in the local newspaper told of increasing clashes on the northern border between Sudeten Germans and Czechs. The leader of the Sudeten German Party was Konrad Henlein who had come to power in 1935 in an election that had been largely financed with Nazi money. On March 28, 1938, Hitler instructed Henlein to increase Sudetenland’s demands for autonomy and its union with Nazi Germany. If the Czech government did not accede to these demands and turn over this part of Czechoslovakia to Germany, Hitler was threatening to support the Sudeten Germans with military force. The Czech government led by President Edvard Beneš turned to Britain and France, hoping that these powers would come to his country’s aid. But this was to no avail. Britain and France were determined to avoid war at all costs. Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain said, “How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom we know nothing…. However much we may sympathize where a small nation is confronted by a big and powerful neighbor, we cannot in all circumstances undertake to involve the whole British empire in war simply on her account.”2

In the end, Czechoslovakia’s allies did not stand up for her at all. The Munich Agreement, signed by Germany, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom, stipulated that Czechoslovakia must cede the Sudeten territory to Germany. In exchange, the understanding was that Hitler would not make any further demands for land. Chamberlain held the signed document in his hand, waving it above his head as he addressed the British public and read aloud the details of the accord. “We regard the agreement signed last night as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again…. My good friends this is the second time in our history that there has come back from Germany to Downing Street peace with honor. I believe it is peace in our time.”3 This could not have been further from the truth.

On October 5, 1938, as German troops were marching unopposed into Sudetenland, Beneš resigned as president, realizing that the fall of his country was inevitable. Almost a third of Czechoslovakia would now be subsumed into the growing Third Reich. The realization that the country was being pulled apart was hitting everyone in town with equal force.

Karl arrived at school on that day with his friend George. All around them, students were huddled in small groups, some talking frantically about the impact of these new developments in the north. Others stood in muted silence, absorbing the news and barely able to comprehend the impact on themselves and their country.

“Everyone looks as if they’re at a funeral,” George commented as the two boys pushed their way past their classmates and climbed the steps of the school building. “The country should have seen this one coming. Sudeten Germans have been clashing with the government forever.”

“No one could have imagined this,” replied Karl. “Countries are simply not carved up like this.”

“Then you’re blind, too,” said George bitterly. There was a long pause and then he added, “Hitler’s not going to stop. He’s got Austria, and now he’s got a part of this country. It’s only the beginning.”

“Stop it!” demanded Karl. “You’re starting to sound more and more like my mother.”

“I think she may be the one who’s got it right after all,” George replied, breathing deeply. “If Hitler can take over a third of our country just like that, who knows what else he’s capable of doing. The man is hungry for more. He’s like a bear that smells blood – he’ll stalk his prey until he devours it all.”

Karl had never heard his friend sound so cynical or contemptuous. The two boys stood silently watching their fellow students begin to assemble for the start of classes. A strange stillness had settled on the school grounds – a sense of dark foreboding.

“There may be an advantage for us in all of this,” said Karl, as the students began to enter the building. “As long as Czechs are focused on Germans, either here or in Germany, perhaps they’ll be less likely to focus on us.”

“I doubt it,” replied George. “I suspect that Jewish families living in the north are going to be flooding into this part of the country. Why would Jews want to stay there knowing how much Hitler hates them – hates us? And if you think Jews are going to be welcomed here, then you’re totally naive. I can’t wait to get out of here,” he added, “to get to Prague where at least it doesn’t feel as if everyone knows you and is watching you. I just wish my family were coming with me. You need to get out, too.”

Within the Reiser household, Leila was particularly distraught over the news of the annexation of Sudetenland. It was difficult for her to understand the bitter fragmentation of her country. Her roots were in Sudetenland, where she had been born and where she still had relatives. And yet, her heart was here with the family she had been with for almost two decades.

Later that day, Karl walked home with Leila after accompanying her to the market to pick up some groceries.

“What would I do without your family?” Leila muttered as she struggled to keep up with Karl’s long stride. “Yours is the only home I know.”

Karl squeezed Leila’s arm reassuringly. He glanced around to make sure no one was listening. Leila’s Czech was extremely limited, and German was the only language she spoke in the Reiser home. But here in public, Karl was cautious about responding. These days, speaking German was probably as dangerous as acknowledging one’s Judaism. He did not want to provoke anti-German sentiments any more than he wanted to incite anti-Semitic ones, and both were easily aroused. He nodded, and ushered Leila along. It was only once they were safely back home and Karl had deposited the groceries in the kitchen that he turned to face her.

“You’re the mainstay of this family, Leila,” he said in his near-fluent German. “We’d be lost without you.” He hugged her lovingly, nearly smothering the tiny woman.

“And you and Hana are like my own.” Leila returned the hug, sniffling loudly, and then shooed Karl out of the way so that she could begin to prepare that evening’s meal.

But the news of the Sudeten takeover was still troubling Karl. He was overwhelmed by the growing fear that his mother and George Popper might be right, that this was only the beginning. There was a smell of war in the air, and it was settling over the country like a thick fog. It had been easy to dismiss the unrest when the events were taking place elsewhere, across the borders. Karl, like many others, had tried to hold fast to the belief that his country was safe from conflict and that if circumstances escalated, other countries – more powerful and influential – would come to Czechoslovakia’s aid. One by one, these beliefs were being eroded.

And the situation continued to spiral downward. That November, in Germany and Austria, Jewish shops and department stores had their windows smashed and contents destroyed in what was being called Kristallnacht – the night of broken glass. One hundred and nineteen synagogues had been set afire and another seventy-six burned down completely while local fire departments stood by. More than two hundred thousand Jews had been arrested. Many were beaten and even killed. Once again, Hitler’s voice shrieked from the radio. Appearing before the Nazi parliament, Hitler made a speech commemorating the sixth anniversary of his coming to power. He publicly threatened Jews, declaring, “In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and have usually been ridiculed for it…. Today I will once more be a prophet: if the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the bolshevizing of the earth and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!”4

That same month, Karl celebrated his seventeenth birthday. What should have been a memorable occasion passed as a non-event in the Reiser household. There was no possibility of festivities given the intense feelings that Kristallnacht had aroused in everyone in the family. As Marie became even more resolute in her urging to leave the country, Karl felt his resolve crumble once and for all. He joined his mother’s camp, advocating for the family’s immediate departure from their home. Meanwhile, Victor continued to pronounce that all was still well.

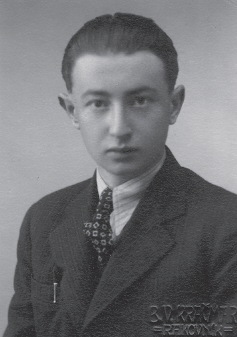

Karl at age 16 in Rakovnik

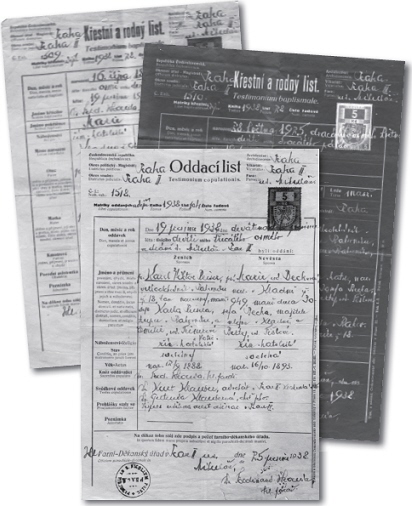

Marie and Victor's Catholic marriage certificate, dated December 19, 1938. Behind are Marie and Hana's false baptism certificates.

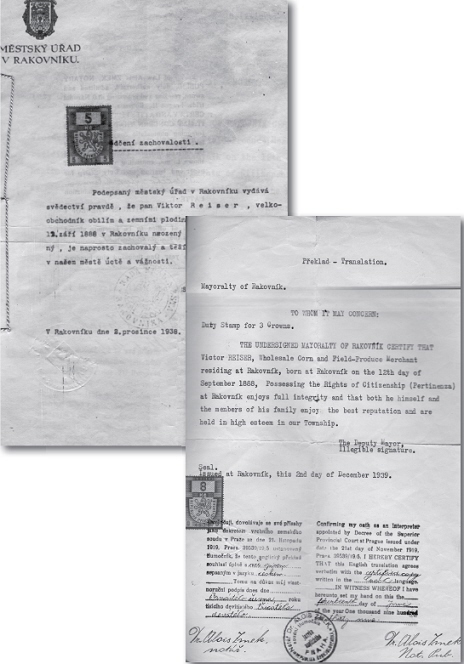

A letter from the Deputy Mayor of Rakovnik (top) dated December 2, 1938, stating that the Reiser family is held in high esteem within the community. The translation (bottom) is notarized in Prague on June 14, 1939, suggesting that Marie must have had the translation done when the family fled there.