Prague 1939

THE WEATHER HAD TURNED quite miserable by the time the Reiser automobile rolled through the streets of Prague. Snow was falling in a steady cascade in one of the worst storms of the season, blanketing a city that lay in wait for its opponents to strike. Few people were outside and those who walked had their heads and eyes down, keeping the business of the world at bay.

The family car headed straight for the villa in the Vinohrady suburb of Prague at 20 Benešova ulice, a beautiful section of the city with tree-lined streets and impressive private homes. It did not take long to unload their luggage and settle into the spacious apartment.

Within hours, just before noon, a gray column of soldiers, tanks, and motorcycles began to roll through the streets. Hitler’s army had arrived and his limousine led the military parade. Generals came next, followed by marching soldiers, their faces set and staring ahead, their boots clomping through the snow in perfect synchronicity.

In the hundreds and thousands, the citizens of Prague came out to witness the arrival of Hitler’s victorious army. They emerged slowly from their homes, shops, and businesses to line the streets and watch the takeover of their country. But there was little cheering, no chanting of slogans, and few sounds of adulation. They would accept their fate, but would not welcome it. Unlike their neighbors in Austria, the people of Prague were not pleased by Hitler’s appearance. Many wept and openly jeered at him. For others, his invasion was met with stunned and stony silence.

Karl and his family remained indoors during the army’s arrival. They stayed out of sight and listened to the distant sounds of marching, wondering what would happen next. During this time, Karl’s mother paced frantically in their new living room. She was anxious to find a way to contact her husband.

“I can’t imagine what your father must be thinking,” she said as she approached the window to glance outside. As she turned away, the satin drapes fluttered closed behind her, blocking the view of the city as the snow continued to fall. “I’m sure he’s been trying to call the house all morning. He’ll be beside himself worrying about what’s become of us.”

Marie was reluctant to use the telephone in the villa to contact her husband. She feared that police or censors might be tapping phones, listening in on conversations. The family’s goal was to be as invisible as possible – no overt contact with the outside world, nothing to draw attention to themselves, particularly as Jews. But by mid-afternoon, Marie could not stand it any longer. She announced to her children that she was going out to find a public telephone.

“I’m terrified that he’s going to make the mistake of returning and I can’t let him do that,” she said. “At least one member of this family is safe outside Czech territory. He’ll be more help to us from France right now than he could ever be here.” She pulled on a heavy wool coat, wrapped a scarf around her head and neck, and headed out into the streets.

While his mother was gone, Karl wandered through the villa from room to room, inspecting this new, temporary home. It reminded him of his home in Rakovník with its tall ceilings, grand chandeliers, and fine Oriental carpets. There was a spacious garden in the courtyard at the back, now covered with snow and looking rather bleak.

Karl longed to watch the activity surrounding Hitler’s arrival. He imagined the dictator crossing the Charles Bridge and emerging from his limousine at Hradèany castle, ready to inspect his troops on this historic occasion. Unbeknownst to Karl, Hitler would make a speech that day, declaring the entire western region of Czechoslovakia to be a German territory called the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and under the rule of German-appointed Reich protector Konstantin von Neurath. In reality, this part of the country would be totally subjugated to Germany. Slovakia in the east would be declared an independent state under its president, Jozef Tiso, another of Hitler’s pawns. Karl knew none of these details then, but he envisioned the Czech flag that flew over the Prague castle being lowered, and replaced with the swastika. And as he pictured the takeover of his country, a vile taste rose in his throat. He wanted to spit in Hitler’s face, just as Hana had spat at the photograph of the SS officer in the photography shop window.

When Marie returned, Karl rushed to the door to greet her and hear the details of her call to his father. As expected, Victor had been frantic with worry over his family’s whereabouts. When news of Hitler’s invasion had reached him in Paris, he had called the house in Rakovník repeatedly but no one knew what had become of his wife and children. The family had left early in the morning and had told no one where they were going. For Victor, it was as if his family had disappeared into thin air, and he feared the worst. And, just as Marie had anticipated, Victor wanted to join them in Prague.

“It took everything in me to convince your father not to come back here,” Marie explained, rubbing her tired eyes. She pulled a lace hankie from her sleeve and wiped her brow.

“How is Father?” asked Karl.

“A nervous wreck,” his mother replied. Marie looked so distraught that Karl could only imagine just how difficult it must have been for her to persuade her husband not to rush to his family’s side. “But now it’s up to him to find a way to get us out of here. And it’s up to us to stay out of the clutches of the Nazis.”

It still felt somewhat unreal to Karl that the danger could be so imminent. But he was becoming increasingly impressed by the accuracy of his mother’s assessments. Karl barely recognized his mother these days. The woman who had quietly stood behind her husband’s authority all the time that Karl was growing up was emerging as a person in charge. Were it not for her, they would certainly never have left Rakovník so quickly.

Three days after Karl and his family arrived in Prague, Victor traveled to Zurich to finish off the business that had taken him out of Czechoslovakia in the first place. While he was there, he met with a notary to have his power of attorney turned over to Marie in Prague. Thanks once again to his wife’s foresight, Victor had at his disposal a sizeable amount of family money that had already been transferred to the Crédit Lyonnais in Paris. Marie would now be in control of what was left of the family’s estate and fortune in Czechoslovakia.

A few days later, Marie met with a notary in Prague and arranged to have her power of attorney assigned to Alois Jirák, the same colleague of their father’s whom Hana and Karl had met in their home weeks earlier. Not only was Jirák a trusted business associate of Victor’s, but, more importantly, he was Christian. Marie and Victor feared that the Nazis might freeze the bank accounts of all wealthy Jews, and hoped that placing their estate in the hands of a non-Jew would protect it from confiscation. In Germany it was already illegal for non-Jews to help Jews hide their holdings. But those laws had not yet arrived in Czechoslovakia.

The discussions for how to proceed with these arrangements were all done by telephone. Marie had found a payphone at the Hotel Paris in the center of Prague. There, she could talk with her husband uninterrupted, and she spoke frequently with him, awaiting his calls at preappointed times, and then returning to relay information to Karl and Hana. Once these financial plans were in place, Marie arranged to meet with Jirák in Prague to seal the agreement.

When she did, she had one more important request. “There are four paintings that we left behind in Rakovník,” Marie said, describing the artwork. “They are the largest paintings we own, wall-sized oil paintings that are hung in the salon. You can’t miss them. I would be devastated to see them destroyed, or worse, to think they had been taken by some Nazi thief. So I want you to take personal custody of them. Do whatever you must do to keep them safe.”

Jirák nodded. “I understand,” he said. “And if the Nazis search your house, I don’t want them taken either. To be on the safe side, I will hide the paintings at my son-in-law’s estate. He lives in the village of Krušovice, close to Rakovník. His name is Václav Pekárek. As you will recall, his son, Jan, attended school with your daughter. The paintings will be safe there. You can be confident of that.”

Marie nodded. Jirák was so sincere, and appeared so earnest, that her fears about losing the works were immediately laid to rest. Her husband had trusted this man and she would do the same. With these arrangements in place, her mind was temporarily eased.

After Marie outlined her agreement with Jirák to him Karl asked, “Will we ever see our home again?”

Marie had difficulty answering her son, and she looked away. After several minutes, she turned back to him. “We can’t worry about that right now,” she said. “For the time being, we’re safe and our belongings will be safe. The most important thing now is to get out of the country and to do it quickly.”

Marie was right. This was not the time to worry about other things. The immediate order of business was to find a way to get out of the country, and do it while conditions were still relatively stable. The Nazis had predicted they would receive the same kind of reception in Czechoslovakia that had met them in Austria. Expecting the support of the masses, they anticipated moving quickly with new laws, including anti-Jewish measures. But because the citizens of Prague did not flock to show their adulation for the conquering army, few restrictions were imposed on Jews in the early days of the takeover, and Karl and his family were able to blend easily and quietly into life in the country’s capital.

Almost immediately, Marie had arranged for Hana to go to school at a local public high school. Hana, bored by the inactivity and confinement of their villa, had been only too delighted to begin attending classes.

“I told you it would be a new adventure,” she told Karl confidently as she headed out for classes one bright morning. The snow and cold had left Prague almost as quickly as it had arrived, and while it was still rather gray and bleak outside, the assault of winter was retreating.

“Just be careful, Hana,” warned Karl. He did not want to jolt his younger sister out of her easy state of mind, but Karl had listened to his mother’s dire predictions about the fate of Czech Jews for too long. For him, it felt as if the country was waiting for the guillotine to fall. Still, Hana laughed easily as she walked out the door.

School was not an option for Karl. He had already missed his final examinations in Rakovník, and it would be impossible to find a place where he could register for exams in Prague without drawing too much attention to himself. He imagined the conversations with school officials; “Why did you leave your home town just as your matura was taking place? Why did you have to leave so quickly? Why could you not wait a few more days – a few more weeks?” These were questions that Karl was not prepared to answer. Although school had never occupied the most important place in his life, he mourned the loss of the completion of his education just as he mourned the loss of his home. He often wondered if their house had been plundered, either by Nazi soldiers or by greedy natives of Rakovník who couldn’t wait to be rid of their Jewish neighbors. Was everything they had once owned now gone?

When his mother found a tutor for him in the city, and he began taking private lessons in Spanish and English, Karl’s days were occupied and he found that he worried less. He also managed to locate his friend, George Popper, who had been attending university in Prague for almost a year. The two young men easily picked up their friendship.

“I’m concerned about my family,” George said one afternoon as he and Karl stood waiting in line at one of the many financial institutions in Prague. Each day, Marie sent Karl to one of the banks to withdraw the legally controlled limit of funds allowable on a daily basis – fifty Czech crowns. Through Alois Jirák, Marie had access to larger sums of money in their estate. However, some of the family’s funds were here in regular bank accounts. “I don’t want the government to have any of it,” Marie insisted. “We’ll get it out of the bank, bit by bit if we have to.”

“Your mother was smart to get you out of Rakovník when she did. I told you that she knew what she was talking about when we were still there,” continued George. “Mine refused to leave. I haven’t heard from my parents in weeks.” Karl nodded sympathetically. He didn’t even want to mention this news to Hana, knowing how she would worry about George’s sister, Rita. It was difficult enough for Karl and his family to be separated from his father, but at least they knew where he was. There were too many rumors that Jews in smaller towns were being arrested. Karl’s mind often wandered to thoughts of the Jewish families in Rakovník. He wondered if they had had the foresight to get out as Marie had.

The line in front of the bank wound its way down the street and around a corner. Now it inched forward ever so slightly. Hundreds of citizens lined up here on a daily basis to try to retrieve their savings. Along with a growing tension in the air was a sense that the market in Prague might collapse, leaving many without financial resources. Karl and George spent long hours here on a daily basis. Still, it passed the time when there was little else for Karl to do.

As for Marie, she was working furiously to get her family out of Czechoslovakia. Through conversations with Victor and various friends and officials in Prague, the family learned that to get out of the country, three key documents were required. The first was Czech passports. They were fortunate that they had these in their possession. The two remaining requirements were a permit from the Gestapo allowing the family to leave and cross the border, and a visa from a country willing to accept them. Victor was trying to acquire the latter. Marie was in charge of the exit permits. But the acquisition of these two key documents was proving to be a daunting task.

“Even if we are able to get out of Prague, what country will take us in?” Marie voiced this concern as she sat with her children in the evenings, discussing her ongoing telephone conversations with her husband and their efforts to obtain the necessary papers. The simple truth was that not many countries were willing to open their doors to Jewish refugees, and more and more were desperate to escape their countries. Many nations thought that by accepting Jews they would be bringing the wrath of Hitler upon themselves. Besides, many refugees had no jobs and no money, and could prove economically burdensome to countries dealing with their own unemployment and poverty. Instead of refusing entry to Jewish refugees outright, many countries made the conditions for entry so difficult that it was nearly impossible to comply. Stringent quota systems on the number of Jews admissible were put into place, adding to the list of obstacles facing Jews who wanted to leave their homelands. All of this conspired to keep Karl and his family in Prague as Hitler’s noose tightened ever so slowly around their necks.

By early June, prominent Czech Jews began to disappear mysteriously. Jewish synagogues across the country were burned down and Jews rounded up and beaten on the streets. Jews were barred from owning businesses and Jewish property was seized across the protectorate. On June 21, von Neurath, the new Reich protector, issued a long list of anti-Jewish decrees, not unlike those already enacted in Germany, all designed to destroy the economic viability of the Jewish population. The seizure of Jewish property became commonplace. And while some Jews were still offered the opportunity to get their exit permits and leave the country, doing so meant that they would have to transfer their capital and property to the Nazis, thus forfeiting all of their belongings.

With their family fortune in the legal hands of Alois Jirák, Marie hoped to avoid surrendering their assets to the Nazi government. She searched the city, spoke to some trusted contacts, and managed to locate a lawyer who said he was willing to help with the exit permits. Marie returned home optimistic after her first meeting with the solicitor.

“He’s charming, and so reassuring,” she said. “I really think he’ll be able to help us.”

Trusting him, she turned over their passports and a large sum of money. She believed that within days, the family would have the necessary papers to leave. Each morning after that, she awoke, ready for the call that would summon her to the lawyer’s office to pick up the documents, and each day there was no such call. Eventually, the lawyer contacted Marie, stating that he was having difficulty securing the necessary papers. He declared that he would need more money if he were to be successful in this task. More hesitantly now, Marie complied and turned over an additional large amount of cash. Still the lawyer did not come through. Reluctantly, Marie began to suspect that she was being extorted by an unscrupulous man. Karl accompanied her on the day she went to his law office.

“I insist that you return our passports,” Marie said firmly when she and Karl were finally ushered in to face the lawyer. She stared evenly at him as she sat on the edge of a large armchair.

Karl stared at the lawyer who was trying to take advantage of his family. He was tall and gaunt, a humorless man with a permanent sneer on his face, so different from the “charming” person that Marie had at first described. He wore an ill-fitting black suit and eyed Marie quietly through thick glasses, returning her stare with one equally cool and detached. “Perhaps if you give me more money, I could do more for you. Money talks, you know.”

Marie rose taller in her seat. “I will not give you one more crown.”

The lawyer raised his eyebrows above his spectacles in a gesture that indicated his complete disdain for Marie. He shook his head. “That’s a great pity,” he replied, ice cold. He then went on to say that he had turned the passports over to his contact at the Gestapo. “Perhaps you’d like to deal with them as opposed to me.”

Karl gulped. This man had them, he thought. There would be no escape after all. Their belongings would be confiscated and his family would simply be fed into the jaws of the Nazis. Karl watched his mother. What could she possibly do in the face of this threat?

Marie paused a moment, and then slowly rose out of her chair to face the lawyer. “I have nothing to lose here,” she said, so quietly that Karl and the lawyer had to lean forward to catch every word. “I have reached the end of my rope and I will do anything to get my family to safety. Unless you return the passports to me immediately, I will go to the Gestapo myself and report you.”

Karl was dumbfounded. This was an incredible and perhaps reckless display of bravado. What influence could Marie possibly have with the Gestapo, and why would they even care if one more Jew was being defrauded? But Marie was calling this man’s bluff, hoping that he would not want any kind of attention brought to himself. How would he respond? He and Marie faced off against each other, staring one another in the eyes, waiting to see who would blink first. The lawyer’s nostrils flared and his breathing made a high-pitched whistling sound. Minutes passed – an eternity. Finally, he rose, turned, and walked over to a large safe behind him. He opened it and reached inside. When he turned around he was holding the family’s passports in his hands. He handed these precious identification papers over to Marie and motioned for her to leave with a wave of his hand, as if he were shooing away an annoying fly. Without uttering another word, Karl and his mother turned and left the office.

Once on the sidewalk they both breathed a deep sigh of relief. But Karl could see that, for all of his mother’s daring, her hands were shaking as she placed the passports securely back inside her purse. She smiled weakly up at her son.

“We won that round, didn’t we, Karl?”

Karl nodded admiringly. But, in the next moment, his heart sank and the sense of victory was replaced with one of despair. They were back to square one. They had no travel documents, no visa, and no means to leave the country.

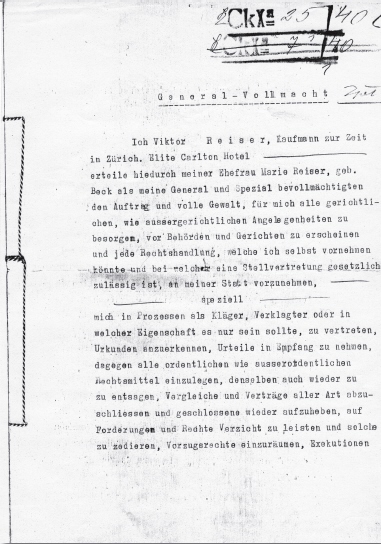

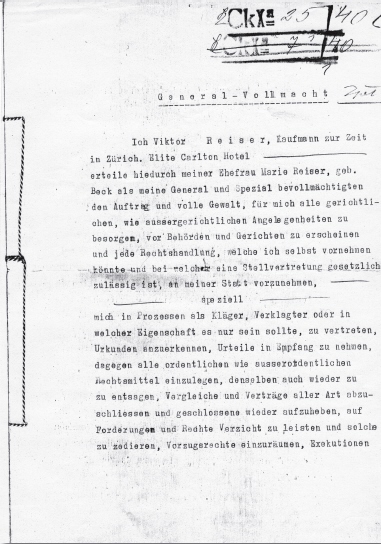

In this first of a three-page document, Victor transfers to Marie full power to deal with all assets, and power to take whatever action in relation to those assets that she deems necessary.

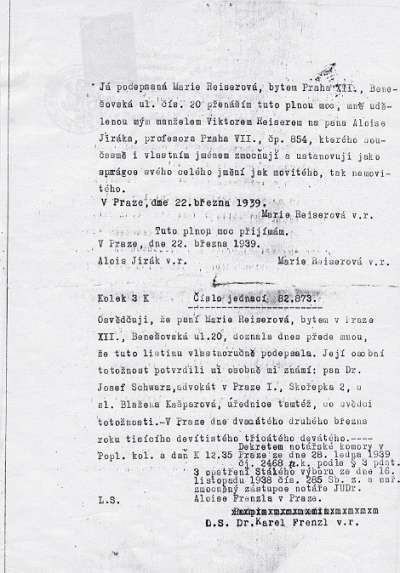

In response to assuming power of attorney from Victor, Marie transfers this power to Mr. Alois Jirák, “professor whom I...empower as an adminstrator of our assets, real estate or other...” At the bottom of the document is a statement by Jirák saying that he accepts this Power of Attorney.