CHAPTER EIGHT

Prague, July 1939

AFTER THE FIASCO with the lawyer, Marie began to proceed more cautiously to obtain exit visas from the Gestapo. It was becoming increasingly clear that few people in Prague could be trusted to help. Swindlers were everywhere, looking for opportunities to take advantage of desperate Jews who were trying every avenue to get out of the country. As hard as his mother was working to secure the exit documents, Karl knew that his father was working equally hard to find a country willing to accept them, and to obtain the necessary entry permits. And by July 1939, it appeared that Victor might be having some luck.

As Karl was returning home from his English lessons one afternoon, the streets were busy with people rushing about at the end of the workday. At first glance, all appeared normal. But a second look told a different story. On every corner and in front of many shops and stalls, there were Nazi soldiers and Czech police patrolling side by side. Their rifles were slung over their shoulders in an almost casual manner. But their eyes were trained on the faces of the people as they passed by. What are they looking for? Karl wondered as he kept his head down and walked quickly toward his home. Were they searching for Jews? And would they recognize him as one if they had a good look? Signs and placards in stores and cafés warned that Jews were not permitted to shop or sit. The flag bearing the swastika flew at every street intersection and draped the tallest buildings. Karl resisted the burning urge to document the pillage of this city with his camera. It had remained tucked away in his suitcase at the flat. A young red-haired man snapping photographs of Nazi soldiers would be a beacon and he was smart enough not to risk this exposure.

As soon as Karl pushed open the front door of their apartment, he was greeted by the most intoxicating smells coming from the kitchen. There was the familiar aroma of caraway, paprika, and dill combining with garlic and onions. He closed his eyes and felt himself transported back home where these smells at the end of the day meant only one thing – a banquet in the dining room and guests for dinner.

Karl followed the smells into the formal dining room at the back of the flat where he was startled to see Leila setting the table with the fine china, silverware, and crystal wine glasses that had been there in the villa when they had arrived. This ceremonial dining ware had seldom been used by Karl’s family. It seemed pointless to dine formally when it was only Karl, his mother, and sister.

Marie was directing Leila from one side of the room but stopped when her son entered. “Karl,” she said brightly, her face more alive than he had seen in weeks. Strands of hair had escaped from her bun and flew about the top of her head. She had a schoolgirl excitement about her. “How were the lessons today?”

Karl nodded. “They were fine. I’m actually enjoying the classes. My English and Spanish are becoming almost as good as my French, Latin, and German.” With his strong aptitude for languages, the classes were proving to be a gratifying challenge.

“Good,” his mother replied, “because English may come in quite handy for you.” She paused and smiled at the puzzled expression on her son’s face. “Let me tell you about my telephone conversation with your father today.”

Marie went on to explain that Victor had made an important contact in Paris earlier that week. He had been working feverishly, desperate to find a country willing to accept them. Rumors were rampant about where to go and which country might be offering visas. As everyone was discovering, there were fewer and fewer legal avenues open. But two countries in particular, Canada and Cuba, had the reputation of having immigration officials who might be willing to accept bribes in exchange for providing those all-important entry documents.

“Your father is worried that the Cuban visas might turn out to be forgeries. That’s what people are telling him. Can you imagine arriving in a country only to be turned back because the papers are counterfeit!” Marie exclaimed as she inspected the placement of the last of the dishes on the dining room table. She turned again to face Karl, her face shining. “But Canada! Your father believes that we have a chance to get genuine entry papers to go there. He’s met a man who’s willing to help us.”

The man was George Harwood, a Canadian official stationed in Paris, working as an agent of the Canadian Pacific Railway in a section known as the Department of Colonization and Immigration. His job was to find and recruit suitable employees to work for the CPR in Canada and to find immigrants who could work the land. “These immigrants are not necessarily meant to be Jews,” continued Marie, “though I imagine there are many, like your father, who are trying to get hired on just to be able to get the papers. But, more importantly, your father has learned that Mr. Harwood is a man who will take money under the table. And that’s what we’re counting on. Remember, money talks, Karl.” She was quoting what the corrupt lawyer had said before he had swindled them out of a large amount, and Karl wondered if Mr. Harwood’s intentions were any more legitimate.

“Mr. Harwood is here in Prague; he’s come to meet some prospective recruits. And I’ve invited him to dinner here tonight!” Marie turned to face her son. “Oh, Karl, we must remain hopeful that this plan will work, and we must impress Mr. Harwood, no matter what. Now, I have so much to do.” With that, she flew out of the dining room, calling instructions to Leila.

George Harwood was a charming and talkative man, who happily accepted Marie’s hospitality as if he were a long-lost friend. “It’s so lovely to enjoy a home-cooked meal, Mrs. Reiser,” he said patting his rather large stomach. He finished off his third plate of food and washed it down with another glass of red wine. From his portly stature he looked as if he had enjoyed many a good meal. “I can’t tell you how tedious it has been to dine in those hotel restaurants night after night.”

Marie, ever the gracious hostess, smiled warmly. “We’re pleased to welcome you, Mr. Harwood. As you can imagine, I haven’t had many opportunities to entertain lately. I miss the dinner parties we used to have. This is a treat for me as well.”

Marie had gone out of her way to prepare a banquet. All of Karl’s favorites were there:  – garlic soup – to start, followed by hovìzí with opekané brambory – beef with roasted potatoes – for the main course. Dessert was the best surprise –

– garlic soup – to start, followed by hovìzí with opekané brambory – beef with roasted potatoes – for the main course. Dessert was the best surprise –  , dumplings with blueberries hidden inside mounds of delicately chewy dough. With restrictions on shopping for Jews, it was difficult to know how she had managed to acquire all of these delicacies. Leila must certainly have helped.

, dumplings with blueberries hidden inside mounds of delicately chewy dough. With restrictions on shopping for Jews, it was difficult to know how she had managed to acquire all of these delicacies. Leila must certainly have helped.

There were other guests for dinner that evening: Mr. and Mrs. Zelenka, the couple that owned the flat that Karl and his family were renting. They also wanted entry visas to Canada, and hoped that Mr. Harwood would be willing to help.

“You have a lovely home here,” Mr. Harwood said, finally pushing away from the table and leaning back in his chair.

“We are very comfortable,” said Marie. “And lucky, thanks to the Zelenkas. But I wish you could see what we left behind, Mr. Harwood. Our books, music, furniture, artwork.” She went on to describe the four large paintings. “They were really quite special. I think I miss those most of all.”

“I love the arts, too,”” said Mr. Harwood. “My family owned a music store in Winnipeg, where I grew up.”

“My son, Karl, has been studying English,” said Marie. “I hope he gets to use it in your country.”

Karl and Hana watched and listened from their spot at one end of the dining room table. They had been told to dress for the evening. Karl wore his best suit, while Hana had on a silk dress in the softest shade of green. It set off her curly red hair and vibrant eyes, but she was quiet. The presence of these guests reminded her of those days in Rakovník when the house had been overrun with unfamiliar faces. The preceding couple of months in Prague had been a welcome opportunity to have her family to herself, notwithstanding the circumstances under which they were there. Karl was glued to the conversation, anxious to hear word of when the family might be leaving and when he would be reunited with his father.

“The country doesn’t want us here anymore – that is becoming abundantly clear. But they’re making it impossible for us to leave.” Mr. Zelenka was speaking and his face was red as he gestured in the air angrily with his knife, hardly noticing the bits of food and gravy that flew in all directions.

“Perhaps things are not as bad as some would suggest.” This statement came from Mrs. Zelenka, a thin woman dwarfed in size and personality by her outspoken husband. “My parents will never leave, no matter what, and I’m still not sure I can leave them behind. They believe that because they are elderly, no one will bother them. ‘What would Hitler want with old Jews?’ my father often asks.” She smiled and others at the table joined her.

“We will all have to leave eventually. That’s what I think,” continued Mr. Zelenka. “Hitler’s right-hand man, Eichmann, is here in Prague right now, trying to push all of us out. He’s even established a branch of the Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung. They say that if you sign up with this Central Office for Jewish Emigration you’ll receive an exit visa. Simple as that! But is it?”

“If Jewish families register with this organization, doesn’t it mean that they have to transfer all of their capital and property into the hands of the Nazis?” Karl asked from his spot at the table, no longer able to resist contributing to the conversation. “That makes it impossible for most families to leave.”

“Exactly my point!” Mr. Zelenka’s head bobbed emphatically. “They want us out, but then they create all kinds of obstacles to our leaving. Some are suggesting that this branch of the SS is merely a front. Jews register to leave and once they come forward, they are arrested and never heard from again.”

Marie recounted the story of how the lawyer had swindled her out of a large amount of money. “Not only that, but he threatened to report us to the Gestapo.”

Mr. Harwood nodded sympathetically. “It’s no easier to get in anywhere, as I’m sure you all know. It was possible a few years ago. But now, Canada and many other countries are reluctant to take in Jewish refugees. There’s a fear that we’ll be flooded with families escaping Europe. Besides, few countries want to alienate Hitler these days.”

“Not even Palestine,” added Mr. Zelenka, shaking his head. “One would have thought that Jews could go there. But the British are worried that there might be another Arab uprising like the one in 1936. So those doors are closed as well.” The Arab revolt against mass Jewish immigration had lasted off and on for three years and had prompted a renunciation of Britain’s intent to create a Jewish national home in Palestine.

There was a moment of silence at the table. Then Mr. Harwood said, “Thankfully, for you and others, I’m able to bend the rules to allow selected immigrants into my country – not an easy task, I assure you.” He stopped short of saying that it would cost these families dearly for the privilege of entering Canada. The details of that would come later.

“We are all so fearful of Hitler’s plans,” said Marie. “Here, there are more and more restrictions emerging on a daily basis. Now Jewish doctors and lawyers can’t practice; professors and instructors can’t teach.”

“And what about those who are being arrested?” asked Mr. Zelenka. “They call it protective custody, whatever that means. Who’s being protected? And where are they going? No one seems to know.”

“First Austria, then Czechoslovakia. What next?” Marie lowered her head and closed her eyes.

“Poland!” declared Mr. Zelenka. “Hitler recognized a valuable prize when he took Czechoslovakia. Not only did he get this vast land, but also it paved the way for further conquests. He’s already denounced the non-aggression pact with Poland and he’s demanding the return of Danzig to Germany. Mark my words: Poland is next.”

“Will no one come to Europe’s aid?” Mrs. Zelenka whispered these words.

Mr. Harwood shook his head. “President Roosevelt has outlined a peace proposal for Europe, but it doesn’t look like Hitler is going to listen to it. I’m afraid we’re headed for all-out war.”

There was silence at the table as each guest digested this pronouncement. Karl was angered by the discussion. How was it that they had become fugitives? They were being forced to leave their homes and were being treated like criminals for no reason. They weren’t wanted in their home country, and they weren’t wanted elsewhere. None of it made sense. Karl’s family had barely acknowledged its Jewish background, but now it seemed to glow above their heads like a spotlight.

“Enough talk of war,” said Marie, shaking her head wearily. “Please enjoy the wine, the meal, and our hospitality, Mr. Harwood. Let’s talk of happier things. Let’s talk of a future in your country.” She raised her glass and said, “To Canada. And to peace!” The others joined her in the toast.

Shortly after that, the Zelenkas said their good-byes and went upstairs to their flat. Marie walked over to Mr. Harwood and extended her hands to him. “I know that you and my husband have discussed the terms under which we might be able to get into your country,” she said, referring to the bribe that would buy them their precious entry visas. “We will complete our part of the agreement. Please fulfill yours. Do not let my family down.” She spoke these last words fervently, staring Mr. Harwood in the eyes and clutching his hands in a forceful grip.

Mr. Harwood nodded. “I’ll meet with your husband as soon as I get back to Paris. When the details are in place, I’ll arrange your visas through the consulate there,” he said, bowing slightly. “Thank you again for the lovely evening.”

Within days, Victor called his wife at a prearranged time on a public telephone to report that the monetary transaction with George Harwood had been completed and the entry visas to Canada would be issued. Karl didn’t know how much money had passed between his father and Mr. Harwood, though he believed it must have been a sizeable amount. What was important was that one more hurdle had been cleared to enable them to leave.

With the visas seemingly secured, Marie turned her attention once more to acquiring the exit permits, the final and perhaps most important documents standing in their way. It was dangerous to try to arrange a meeting with the Gestapo. Notwithstanding the power of attorney in the hands of Alois Jirák, Marie knew that she would risk having to disclose their family fortune if she were to meet with Nazi officials. And she worried that by concealing their wealth, she was jeopardizing the safety of her family. If the Nazis were to discover this deceit, not only would they confiscate the estate, but they would probably also arrest the Reisers. The Gestapo did not need a reason to take a Jew into custody. Marie could chance none of this.

But the pieces were falling into place, one by one. Once again, Marie cast out her net and pulled in contacts. She discovered that in the town of Zlin there was a Gestapo official who, like George Harwood, was known to take bribes. This was all she needed to know. She awoke early one morning and announced to her children that she would be traveling by train to Zlin, staying there overnight, and would return later the next day.

“I haven’t even told your father these details,” she said, before leaving the villa. “Better not to worry him too much more.” Though Victor had remained in Paris as per his wife’s wishes, the stress of being separated from his family was taking its toll. Marie knew this from their telephone conversations and she in turn worried about her husband’s health. “I’ll give him the good news tomorrow, after I’ve got the papers in my hand,” she said brightly.

Karl wondered if her optimistic attitude was merely a front for the anxiety that she surely must have been feeling. He too was anxious for his mother’s safety, though he could not state these concerns. He watched her, wondering how she was ever going to pull off this feat. What Gestapo official would agree to meet with a Jew, let alone a woman? But Karl knew that his mother had already proved herself capable of accomplishing the impossible, and Karl prayed that this journey to Zlin would be no exception. When he saw her striding confidently up the sidewalk toward their apartment the following evening, he knew that she had accomplished her mission.

“I’ve got them,” she announced jubilantly as she entered the villa and grabbed her children in a fierce embrace. “Imagine! It only took a few minutes.” She went on to describe the trip. The train ride to Zlin had been the most anxiety-provoking part of the journey. In every car, Nazis patrolled the aisles or mingled with passengers. Marie’s greatest fear had been that she might be asked for her papers and questioned. It would have been difficult, under Nazi scrutiny, to hide her religion. But the trip passed uneventfully. Perhaps the guards had passed her by because she looked so refined. Several actually had nodded at her and she had forced herself to paste a smile on her face as she hid her trembling hands in her lap. In Zlin, she proceeded to Gestapo headquarters, and asked to speak to the official whose name she had obtained. He saw her immediately.

“Like being close to the devil himself,” Marie described. “That’s what it felt like in the room with that man staring at me.” She breathed in deeply before continuing. “I took the envelope of cash from my purse and slid it across the table toward him. He would never have taken it from my hand – wouldn’t dare touch me, a Jewess. But my money was certainly good enough for him. We barely spoke, we didn’t need to. He knew why I was there. Look Karl, Hana, my hands are shaking even now as I think about it.”

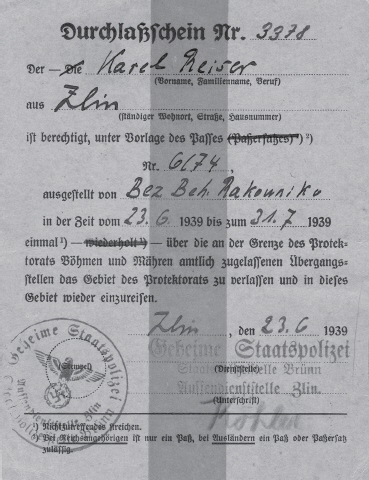

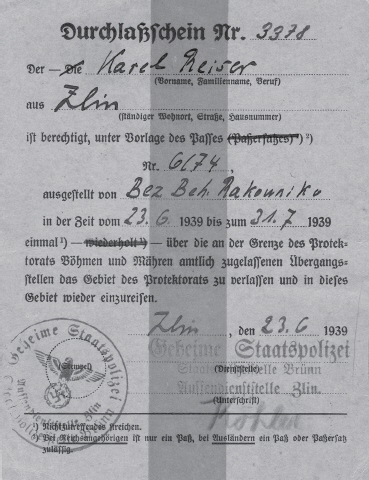

Karl could only imagine what it must have been like for his mother to face this Gestapo officer and ask for the exit papers. Her initiative and sheer guts were more impressive than ever. In exchange for payment, Marie had left the building with the exit permits in hand. Proudly, she displayed the documents to her children, one in her name and one in Karl’s name. Hana would travel under her mother’s passport. Everything was now in place, but Marie was still worried.

“What if these permits are invalid?” She voiced her apprehension that evening as they celebrated the acquisition of the documents. All the necessary papers lay on the table in front of them: passports, exit permits, even the false baptism papers and Catholic marriage certificate. This accumulation of documentation had more value to the family than their entire estate. And Karl knew that they were luckier than most to have collected them. There was the underlying sense of a near stampede in Prague as other Jewish families were desperately trying to acquire the very papers that the Reisers had lying in front of them. “What if the exit documents are forgeries, or stolen from someone else?” Marie continued. “What if that Gestapo official deceived me, just as that terrible lawyer did? Without proper papers, we could be stopped at the border and that would be that.”

Chances were, with invalid papers, not only would they be turned back from the border, they would be arrested. Though sanctions against Jews had been slower to take effect in Prague, this infraction would no doubt lead to severe consequences.

“I do have one idea,” Marie said, turning to Karl. “But you are going to have to agree to this.”

What now? Karl wondered.

“I want you to test these documents for us.” It seemed that Marie had already thought this plan through. “I want you to get on a train to Paris with your permit. If you can get through passport control at the border, then we will know that the papers are good.” Once safely in France and reunited with his father, Karl would notify his mother and sister to come immediately.

The plan hung in the air as Karl digested its implications. “You’re smart and quick, Karl,” Marie added, reaching across the table to take her son’s arm, as if to pass her strength to him. “You can manage any situation. I’m sure of that.”

Karl swallowed and nodded. This had an ominous tone to it. But he knew what he had to do. He was being asked to put himself on the line, to test these waters for the family. And, in the absence of his father, he was the only one who could do it.

Karl's exit permit issued by the Gestapo in Zlin, June 23, 1939.

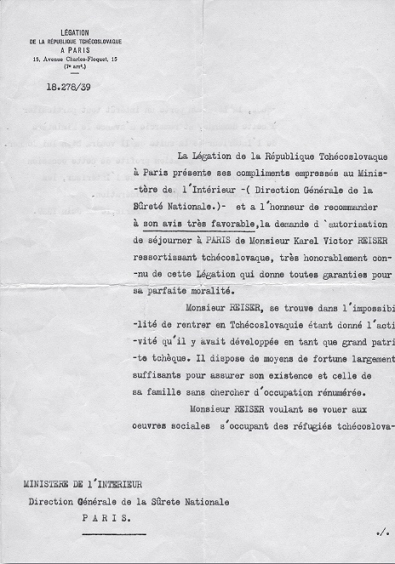

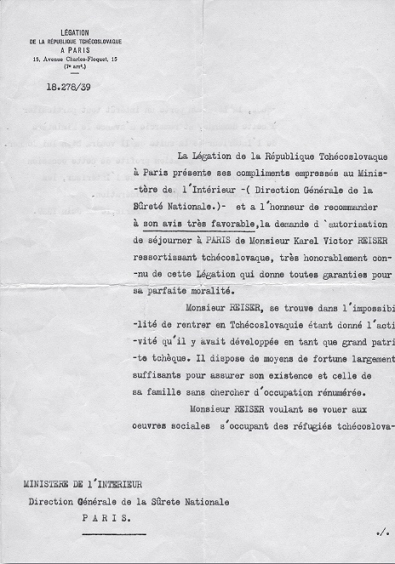

A two-page document issued by the Czech Embassy in Paris.

This document enabled Victor to remain in Paris while trying to get his family out of Czechoslovakia. It provided support to him in his efforts to obtain his “carte d'identité,” the official papers needed to remain in France during the war.

– garlic soup – to start, followed by hovìzí with opekané brambory – beef with roasted potatoes – for the main course. Dessert was the best surprise –

– garlic soup – to start, followed by hovìzí with opekané brambory – beef with roasted potatoes – for the main course. Dessert was the best surprise –  , dumplings with blueberries hidden inside mounds of delicately chewy dough. With restrictions on shopping for Jews, it was difficult to know how she had managed to acquire all of these delicacies. Leila must certainly have helped.

, dumplings with blueberries hidden inside mounds of delicately chewy dough. With restrictions on shopping for Jews, it was difficult to know how she had managed to acquire all of these delicacies. Leila must certainly have helped.