CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Prague 1947–8

SHORTLY AFTER Marie and Arthur’s departure to Prague, Karl and Phyllis gave up their apartment in the west end of the city and moved into the family house on Rosedale Heights Drive. There they waited for news from Marie. It was difficult to get information. Through sporadic letters and even more infrequent telegrams, Karl was able to learn the full details of what unfolded in Prague only many months later.

When Marie and Arthur returned to Czechoslovakia, they took up residence in a spacious flat in Prague and began to take stock of what had happened to the country following Nazi Germany’s surrender. Like many European countries, Czechoslovakia was in the process of rebuilding, and in April 1945, the Third Republic of Czechoslovakia came into being. This was a coalition government consisting of three parties: the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia – Komunistická strana  – the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. At the time there was great support for the KSÈ, which had strong ties to the Soviet Union, the country that had liberated Czechoslovakia in the final days of the war and was now directing much of its future. The

– the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. At the time there was great support for the KSÈ, which had strong ties to the Soviet Union, the country that had liberated Czechoslovakia in the final days of the war and was now directing much of its future. The  was determined to become the country’s primary political force.

was determined to become the country’s primary political force.

In the spring election of 1946, Edvard Beneš, who had resigned in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement, returned to Prague and was formally confirmed to his second term as president of the republic. However, the election results gave the  a majority of the vote. More importantly, the Communists were able to gain control of all key ministries, with power over the police, the armed forces, education, social welfare, agriculture, and the civil service. The Communist leader, Klement Gottwald, became prime minister. He was viewed as a moderate who would respect the Czech tradition of democracy; this was reinforced when he proclaimed his desire to lead the country to a thorough “democratic national revolution.”7

a majority of the vote. More importantly, the Communists were able to gain control of all key ministries, with power over the police, the armed forces, education, social welfare, agriculture, and the civil service. The Communist leader, Klement Gottwald, became prime minister. He was viewed as a moderate who would respect the Czech tradition of democracy; this was reinforced when he proclaimed his desire to lead the country to a thorough “democratic national revolution.”7

It was into this new and promising political climate that Marie and Arthur arrived. Those early days in Prague were good. The country seemed to be thriving in the promise of prosperity for all. It almost felt to Marie as if life had returned to what it once was. There was a free press in place, freedom of religion, equal rights for women, an independent judiciary, jobs, and the right to education and recreation. Wealth was being restored, and art and music were thriving.

In the early days, Arthur was happily reunited with his son, who had managed to survive the war in one of the concentration camps of Poland. Karl could only imagine Arthur’s joy at this happy discovery. Almost immediately, Marie started looking for news of the fate of the Jewish community in Rakovník. The first discovery was devastating. Not one other Jewish family in their hometown had come through the war intact. Apart from the Reisers, only George Popper had survived. Everyone else had remained in town when Marie had packed up the family and fled to Prague, and all had been arrested by the Gestapo shortly thereafter, eventually perishing in Hitler’s death camps. The grief cut deeply as Marie remembered her friends, her neighbors, the dinner parties with the Poppers – everything was gone. It was unthinkable. The Rakovník that she had known no longer existed.

The only thing that remained was the house on Husovo  the central square, and Marie focused on it as though getting it back would restore one small piece of the world she had once known. She discovered that the family home had indeed been confiscated by the Gestapo shortly after they had fled. When Marie inquired as to the property’s current status, she learned that the house was now in the possession of the Czech government and had been converted into the local headquarters for the Communist party. Despite her best efforts and those of the attorney she had retained, there was nothing she could do to reclaim the house. Everything that Victor had worked for, everything that they had built together, their entire estate had vanished, swallowed up first by the Nazis and now by the Communists.

the central square, and Marie focused on it as though getting it back would restore one small piece of the world she had once known. She discovered that the family home had indeed been confiscated by the Gestapo shortly after they had fled. When Marie inquired as to the property’s current status, she learned that the house was now in the possession of the Czech government and had been converted into the local headquarters for the Communist party. Despite her best efforts and those of the attorney she had retained, there was nothing she could do to reclaim the house. Everything that Victor had worked for, everything that they had built together, their entire estate had vanished, swallowed up first by the Nazis and now by the Communists.

But Marie would not stop there. Seized by the realization that she would never be able to reclaim the family home, she believed that there was perhaps one part of the family property that had escaped Nazi confiscation. And that was the four paintings that she had left in the possession of Alois Jirák. Marie clung to the hope that the paintings had been moved to Jirák’s son-in-law’s home in the country for safekeeping, and had remained safe there, out of the Nazis’ hands. To Marie, the paintings seemed to represent, more than anything else, the freedom that the family had once enjoyed. They were all that remained of the family’s legacy.

Marie tracked down Alois Jirák. Mr. Jirák, she discovered, had made it through the war with his family, living in his estate outside of Rakovník. Like many Czech citizens, he had managed to do his work and remain under the radar of the Nazi machinery.

Marie’s reunion with him was not a friendly one. All of the respect that he had shown to Victor when they had done business together was gone, replaced with a cold reserve and disdain for Marie and her circumstances. After a short and awkward greeting, Marie got down to business.

“I’m not here to talk about our estate,” she began. “The property is gone – in the hands of the government now. And I realize there is nothing I can do about that.”

Mr. Jirák nodded, his eyes narrowed, and he stared at Marie without responding.

“I’m grateful that you handled our power of attorney back then,” she continued. “You helped my husband and me to hold on to the funds that enabled us to get out of the country safely. Not everyone would have helped in that way.”

Mr. Jirák continued to stare.

“But before we left Prague, I entrusted you with four paintings that hung in our home in Rakovník.”

At that, Mr. Jirák raised his eyebrows slightly. “Paintings?” he asked.

Marie nodded. “Yes, four of them. Surely you remember. At the time, you said that you were going to take them to your son-in-law’s estate in the country. You said they’d be safer there in case the Nazis came looking. I’m assuming you still have them and I’d like to take them back now.”

Mr. Jirák turned his head and gazed away. A long moment passed and neither spoke. Marie held her breath in anticipation of what Mr. Jirák would say. Finally, he turned back to face her.

“Yes, I remember now,” he said. “Four of them, you say?”

Marie nodded.

“Right. Well, I’m afraid they’re gone. The Gestapo came to search Václav’s house – my son-in-law, Václav Pekárek. Everyone was being searched, you know. You think only the Jews were in danger? Well, that’s not the case. We all were. The Nazis wanted everything they could get their hands on.” Mr. Jirák paused. When he said the word Jew, Marie sensed his contempt and she felt her anger rising. She fought to control herself.

“At any rate,” Mr. Jirák continued. “They searched the home several times, went through all of our things, and, on one such search, they confiscated the paintings – took them off the wall and carried them out the door. Who knows what became of them. I did my best, you know,” he added. “As you yourself said, there were not many like me who were willing to help you and others in your situation. Be grateful you got away with your lives. Not everyone was as lucky as you were.”

Mr. Jirák continued talking, but by now Marie had stopped listening. The paintings gone? She couldn’t imagine it and, what’s more, she didn’t believe it. Maybe it was the fact that Mr. Jirák would not meet her eyes, or that he claimed too emphatically not to have the paintings. That intuition, so predominant in Marie, kicked in once more and convinced her that Mr. Jirák was lying. The rest of the property may have been taken, and for that there was no recourse. But in her heart Marie believed that the paintings were safe, and she became even more determined to get them back.

Almost immediately after leaving Alois Jirák, Marie proceeded to the law office of Václav Jukl, where she described the events of her family’s departure from Czechoslovakia, Alois Jirák’s role, and her strong suspicion that he was now in possession of her property. With her usual determination, Marie made the decision to begin legal action against Alois Jirák.

Several letters were exchanged between Marie’s lawyer and the attorney that Jirák retained upon learning that Marie was planning to sue him. It did not take long for Mr. Jirák to confess a new version of his story. In this account, he claimed that the paintings had remained safe in his home during the war. He reiterated that the Gestapo had searched the house, and had questioned him several times as to the origin of the paintings. He reminded Marie of the consequences that might have resulted had they discovered that he was hiding Jewish property. Jirák stated that he had sold the paintings a couple of years after the war ended. He claimed that it was his belief that the power of attorney granted by Victor and Marie entitled him to dispose of the paintings in any way he wished, since he had had no way of knowing whether or not the Reiser family had even survived. Marie’s arrival back in Prague had come as a complete shock to him, which had prompted his first lie. The paintings, however, were still gone, he continued to claim, and there was nothing more that anyone could do to retrieve them.

Once again, Marie was not convinced. Several more letters passed between the two attorneys. Marie’s lawyer continued to press for the return of the paintings, while Mr. Jirák hung on to his story that the paintings were gone and Marie should abandon her mission.

Meanwhile, back in Toronto, Karl wondered and worried about his mother. By the summer of 1947, the political situation in Czechoslovakia was again becoming precarious. All of the assurances of a moderate transition to power for the Communists, one that would respect the Czech tradition of democracy, were rapidly disappearing. The Communist-dominated police, under the control of the Ministry of the Interior, began to increase its intrusiveness in the lives of Czech citizens. The  , with Soviet support, was beginning to accelerate its drive to total power. Toronto newspapers were filled with ominous predictions that Czechoslovakia would be caught up in the whirlwind of conflict that was spinning and escalating between the Soviet Union and the United States.

, with Soviet support, was beginning to accelerate its drive to total power. Toronto newspapers were filled with ominous predictions that Czechoslovakia would be caught up in the whirlwind of conflict that was spinning and escalating between the Soviet Union and the United States.

“‘Moscow’s strategy will be to spark revolutions throughout Europe. And Czechoslovakia will be the first step.’” Karl was scanning the papers and reading sections aloud to Phyllis as the two of them discussed for the umpteenth time the declining circumstances abroad. “Look here. This reporter compares the stand-off between the Soviet Union and the U.S. to a contest between neighbors who are trying to see who can live the longest. The rules of the contest provide that the survivor gets the property of the one who dies first, so it’s more than mere academic interest at stake. It is a real ‘we or they’ proposition.”8 He looked up incredulously. “I can’t believe the world is in this position again. There are some who are even talking of a Third World War.”

“Your mother hasn’t written much lately,” Phyllis replied uneasily. “But even the letters that we’ve had from her say so little about what is going on there politically.”

“Mother would never want to worry us. Don’t you know that’s her style? She’d rather write about what she can buy with whatever declining currency she has than talk about any danger to her or to Arthur.” In her sporadic letters to Karl, she had written that she was trying to do as much shopping in Prague as possible. Remarkably, the money that she had left in the country years earlier was still there, in bank accounts that had remained untouched, in the same financial institutions where Karl had lined up daily to withdraw small amounts of cash. Now Marie was trying to use up as much of it as possible, though she admitted in her correspondence that there was little to buy.

Karl pointed again at the newspapers. “Look, they’re saying that Czechoslovakia is a key location in Europe.” He sat back in his chair, shaking his head. “No wonder Hitler was anxious to control the country years ago. And Stalin is the same. He won’t let it be. And he won’t stop there. Even if the West ignores what’s happening to Czechoslovakia, anyone who thinks appeasement will work on the Communists doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”

There was a tense silence in the room. “There’s nothing you can do,” Phyllis finally said. “You know your mother will decide things for herself.”

“All I know is that I wish she’d leave Czechoslovakia behind and get back here safely.” He looked up suddenly. “My father must have felt like this when he was in Paris and we were stuck back in Prague before the war.” No wonder his father had suffered so much in the absence of his family. Karl now experienced a feeling of complete helplessness. In the face of the rising animosity between the United States and the Soviet Union, he was terrified that if the situation deteriorated, his mother might actually be trapped in Czechoslovakia again, this time under Communist rule.

Karl wanted his mother home for personal reasons, too. By late 1947, he and Phyllis were expecting their first child, and he hoped his mother might be there for the birth of her first grandchild.

Back in Czechoslovakia, the lawyers remained at an impasse. Then, in late 1947, there was a new turn of events. Mr. Jirák finally confessed that he was in fact in possession of the four paintings. Despite his continued insistence that the Gestapo had searched his son-in-law’s house on several occasions, Jirák admitted that he had managed to keep the artwork hidden away. The paintings were safe. A letter from his lawyer stated that Mr. Jirák was willing to return three of the four paintings: the children in the bathhouse, the dancer, and the forest inferno. The fourth one, the one called Die Hausfrau, would remain in the possession of his son-in-law as payment for having taken such risks to hide the paintings in the first place. It was only fair, the letter stated, that Mr. Jirák and his family be compensated for all they had done for the family during the war. One painting would settle this dispute once and for all.

Jirák’s offer was not what Marie wanted to hear. At first jubilant over the discovery that the paintings were indeed safe, she was angry to think that Jirák would hold one back from her. She could acknowledge that he had risked his family’s life to hide their belongings, and for that, she was extremely grateful. Indeed, she would have given him a substantial reward for having kept the paintings safe, anything except one of them in payment. It was her decision to determine the fate of the paintings, she reasoned, not his.

More and more, the paintings were taking on a particular symbolic importance for Marie. There were four paintings; there had been four members of the Reeser family. Keeping the family together in their prewar flight from Europe had been Marie’s primary objective. Keeping the four paintings together was now taking on the same significance. “They are all that is left of our home and belongings, and I will not abandon any of them. I would no more leave a painting behind than I would have left a member of my family behind during the war,” Marie declared. “I will not separate the paintings.”

The response letter from Marie’s lawyer was emphatic. In it, he stated that Mr. Jirák’s responsibility had been to protect the paintings as per Marie and Victor’s instructions. Jirák had no jurisdiction to sell them or keep them, no matter how much time had elapsed since the end of the war. Marie wished to settle the matter quickly, but under no circumstances would she relinquish one of the paintings. With this stalemate firmly established, there appeared to be no alternative but to move to a court hearing. The fate of the paintings would have to be settled in a courtroom before a judge.

In December 1947, Hana traveled to Prague to be with her mother. Taking a break from the stress of the pending court hearing, the family decided to go on a skiing vacation to  . This scenic resort in the Krkonoše Mountains was one of the most popular sites in northern Czechoslovakia, famous not only for its skiing, but also for its hiking and biking trails. Cottages, chalets, and hotels dotted the valleys in the shadow of several giant mountain ranges. The air was crisp, and the green tops of the pine trees looked beautiful as they emerged from under cascades of snow. Here, it appeared as if nothing had changed from before the war. The trip was a reminder of days gone by when the family had taken many such vacations.

. This scenic resort in the Krkonoše Mountains was one of the most popular sites in northern Czechoslovakia, famous not only for its skiing, but also for its hiking and biking trails. Cottages, chalets, and hotels dotted the valleys in the shadow of several giant mountain ranges. The air was crisp, and the green tops of the pine trees looked beautiful as they emerged from under cascades of snow. Here, it appeared as if nothing had changed from before the war. The trip was a reminder of days gone by when the family had taken many such vacations.

Hana was a strong and accomplished skier. It was while she was there with her mother and Arthur that Hana was introduced to Paul Traub, a man ten years her senior. Paul was a quiet, intelligent, and deeply thoughtful man who had studied to become a physician before the war began. His relatively young life and career, like that of so many others, had been tragically interrupted by the war and his arrest and subsequent deportation to the Auschwitz concentration camp. He had survived while most of his family members had not, and, in the wake of the war, he too had decided to return to his homeland. Paul and Hana decided to ski together, but while descending a particularly difficult mountain, Paul fell and broke his shoulder. This ended his skiing holiday, but it was the beginning of a growing affection between himself and Hana. They knew they were meant to be together.

When the family returned to Prague, there appeared to be a growing political tension in the air. The news was filled with the dissension between the United States and her allies in the west and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in the east. Czech military forces were being trained to handle the Soviet equipment and weapons that were regularly arriving in the country in large quantities. It felt as if Czechoslovakia was arming for war. Unbeknownst to anyone, Klement Gottwald and his  party were beginning a covert plan for a Communist seizure of power. They would not wait for the elections due to take place in the spring, and allow the possibility of defeat.

party were beginning a covert plan for a Communist seizure of power. They would not wait for the elections due to take place in the spring, and allow the possibility of defeat.

It was during this time that a strange turn of events occurred with respect to Marie’s attempts to reclaim the paintings. In a letter from her attorney to Jirák, she appeared to abandon her mission. The correspondence indicated that, while she did not relinquish her right to ownership of the paintings, she did wish to withdraw legal action. In addition, she agreed to cover the legal costs that Jirák had incurred in the intervening months. From Jirák’s perspective, this was a complete victory and a vindication that he had done the right thing all along.

When Karl heard that his mother was abandoning the lawsuit, he was somewhat relieved. “At least this means that she will get out of there before the political situation worsens,” he reasoned. Marie must have anticipated that a Communist takeover was imminent. Knowing that she would have to leave or be caught in this new oppressive net, Karl assumed that his mother had come to the conclusion that there would be no point in proceeding further with the lawsuit.

“But the paintings,” questioned Phyllis. “After all she’s tried to do to get them back, why would she stop now?”

It was a good question, and Karl had no answer. “She still maintains that all four paintings belong to her and to our family,” he said. “Knowing my mother, she may even be thinking that once this new political unrest has passed, she’ll go back to Czechoslovakia and pick up the fight where she left off. I’m sure this isn’t the end of the road.”

In February 1948, the Communist party under Klement Gottwald assumed full control over the government of Czechoslovakia. The country became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. This event would become significant beyond the impact on Czechoslovakia alone, as it paved the way for the drawing of the Iron Curtain, and the full-fledged Cold War between the East and West for the next four decades.

Karl’s heart nearly came to a standstill when he picked up the newspaper in Toronto in late February and read the headlines. “Lesson for appeasers seen as Bolshevists grab Czechoslovakia.” The article that followed read:

So democratic little Czechoslovakia has gone the way of all countries upon which bolshevism has managed to obtain a firm grip.

Czechoslovakia’s absorption is one of Moscow’s greatest successes. As the London News Chronicle pointed out a few hours before the coup was achieved, if the Communists gained complete control in Czechoslovakia it would be their most important victory in Europe, because out of all their conquests the Czechs would be the first with an instinctive belief in western democratic freedom. Well, bolshevism reigns in freedom-loving Prague – at least for the time being.9

Marie knew that she would have to get out of Czechoslovakia quickly. The borders were about to close. The memories of fleeing Prague once before rushed back into her consciousness. It was mind-boggling that her country was again forcing her to flee. She had returned believing that she and Arthur could build a stable home in the country she loved. And for a short while it had appeared as if that might be true. But now her heart ached, first for the homeland she was losing for the second time, but perhaps even more so for the loss of her precious paintings. They would remain behind, sealed within the same borders that were forcing her out for a second time. Marie, Arthur, and Hana quickly packed a few suitcases and boarded a plane for Toronto. Paul Traub, the man Hana intended to marry, was not allowed to leave with her. He was refused an exit visa by the new Minister of the Interior on the basis that, as a physician, he was needed by the country. In response, he claimed that his arm, which he had broken while skiing with Hana, made it impossible for him to practice any longer. Eventually, after paying a substantial bribe, Paul managed to get the necessary exit visa. He left the country quickly, taking no belongings, and was met in New York by a relieved Hana.

Karl was thankful to have his family back on Canadian soil. Upon his mother’s arrival in Toronto, Karl questioned her about the paintings and the lawsuit. Marie’s response was clear and firm. “You can forget about them,” she said. She and Karl never spoke of the paintings again.

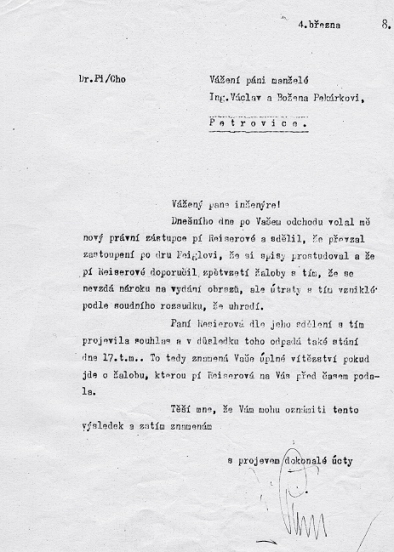

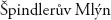

A letter from Marie’s lawyer advising that she has agreed to withdraw legal action for the return of the paintings, while not relinquishing her claim to them.

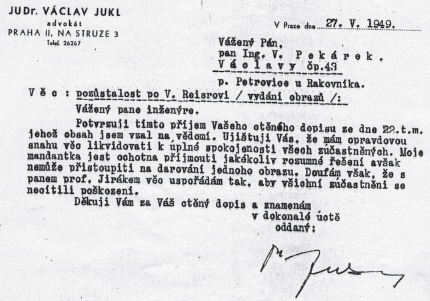

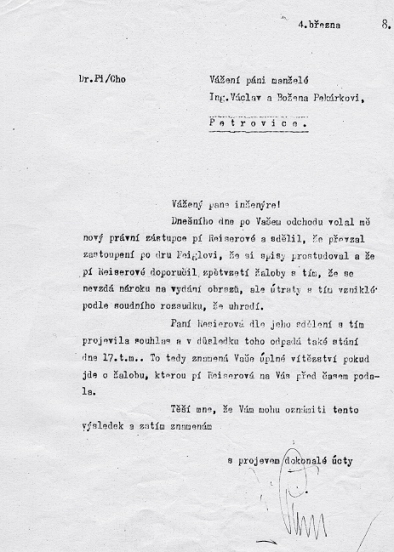

Written by Václav Juki, Mario's attorney in Czechoslovakia, this letter states that Marie is prepared to accept any reasonable solution to the matter of the four paintings, except relinquishing one of them.

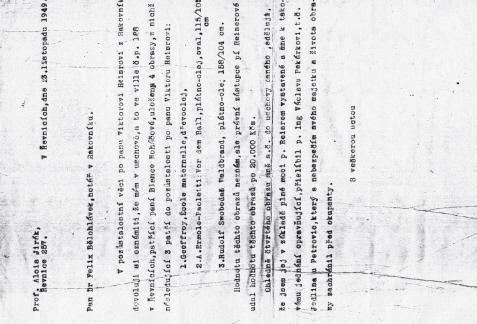

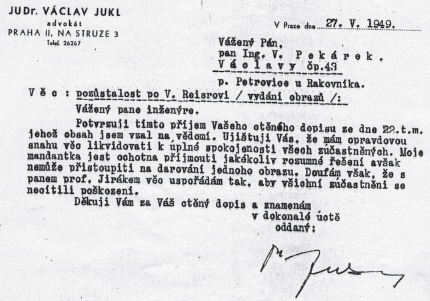

A statement from Alois Jirák to his laywer, which lists three of the paintings and describes that the fourth one was promised to his son-in-law, Václav Pekárek, “who risked his life and property to safeguard the paintings from occupation forces.”

– the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. At the time there was great support for the KSÈ, which had strong ties to the Soviet Union, the country that had liberated Czechoslovakia in the final days of the war and was now directing much of its future. The

– the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. At the time there was great support for the KSÈ, which had strong ties to the Soviet Union, the country that had liberated Czechoslovakia in the final days of the war and was now directing much of its future. The  was determined to become the country’s primary political force.

was determined to become the country’s primary political force. the central square, and Marie focused on it as though getting it back would restore one small piece of the world she had once known. She discovered that the family home had indeed been confiscated by the Gestapo shortly after they had fled. When Marie inquired as to the property’s current status, she learned that the house was now in the possession of the Czech government and had been converted into the local headquarters for the Communist party. Despite her best efforts and those of the attorney she had retained, there was nothing she could do to reclaim the house. Everything that Victor had worked for, everything that they had built together, their entire estate had vanished, swallowed up first by the Nazis and now by the Communists.

the central square, and Marie focused on it as though getting it back would restore one small piece of the world she had once known. She discovered that the family home had indeed been confiscated by the Gestapo shortly after they had fled. When Marie inquired as to the property’s current status, she learned that the house was now in the possession of the Czech government and had been converted into the local headquarters for the Communist party. Despite her best efforts and those of the attorney she had retained, there was nothing she could do to reclaim the house. Everything that Victor had worked for, everything that they had built together, their entire estate had vanished, swallowed up first by the Nazis and now by the Communists. . This scenic resort in the Krkonoše Mountains was one of the most popular sites in northern Czechoslovakia, famous not only for its skiing, but also for its hiking and biking trails. Cottages, chalets, and hotels dotted the valleys in the shadow of several giant mountain ranges. The air was crisp, and the green tops of the pine trees looked beautiful as they emerged from under cascades of snow. Here, it appeared as if nothing had changed from before the war. The trip was a reminder of days gone by when the family had taken many such vacations.

. This scenic resort in the Krkonoše Mountains was one of the most popular sites in northern Czechoslovakia, famous not only for its skiing, but also for its hiking and biking trails. Cottages, chalets, and hotels dotted the valleys in the shadow of several giant mountain ranges. The air was crisp, and the green tops of the pine trees looked beautiful as they emerged from under cascades of snow. Here, it appeared as if nothing had changed from before the war. The trip was a reminder of days gone by when the family had taken many such vacations.