Zurich–Prague, May 22, 1989

KARL ADJUSTED his airline seat into a reclining position and closed his eyes, trying to take advantage of the only solitude he might have for some time. He was on a Swissair flight from Istanbul to Zurich, a two-hour journey. He would spend one day in Zurich and then board a plane for Prague. But it was difficult to relax. His mind beckoned him back and forth in time, a siren call to the events of the preceding weeks, and those that lay ahead.

He had been fully engaged in the tour of Turkey, immersing himself in history and photography as he always loved doing, and enjoying this fascinating country. He had explored archeological sites, museums, mosques, and scenic countryside in a jam-packed tour from Ankara to Istanbul. But as captivating as Phyllis’s itinerary had been, Karl had often felt his mind turning to the pending trip to Prague and his meeting with the grandson of Alois Jirák. At the thought of Jan Pekárek, Karl felt a fresh stirring of anxiety and uncertainty. Pekárek had never responded to Karl’s reply letter in which he had indicated that he was coming for this visit.

So many things could have gone wrong already, Karl thought. Perhaps his letter had never arrived in Prague. It was entirely possible that it had been opened and confiscated by the secret police who regularly tampered with the mail. In that case, who knew what might have already happened to Mr. Pekárek? He might have been interrogated or arrested for trying to conceal valuable goods from the government. In another scenario, Karl imagined that perhaps Pekárek had received the letter but was too anxious to go any further. One letter confessing to the fate of the paintings might have been enough and now, in response to Karl’s eager reply, perhaps Mr. Pekárek wanted to withdraw his offer to finally reunite Karl with his family’s property, and regretted that he had even initiated the process.

But, more than anything else, Karl feared that by now the paintings had already found their way into the hands of the Communists. If Pekárek had indeed begun to inquire as to how to get the paintings out of the country, then the authorities may well have become suspicious. It was unlikely that anyone would put forward such a request if they didn’t have property of value to inquire about. Could he come this close to fulfilling Marie’s dream only to have it dissolve into thin air once more?

On top of that, Karl was feeling skeptical of Jan Pekárek’s offer to return the paintings. What motive would he have for contacting Karl after so many years? Was he after a reward? Karl wanted to believe that Pekárek’s intentions were genuine. But with Alois Jirák’s history, Karl worried that his grandson might be similarly deceptive. It was entirely possible that Karl was traveling all this way, possibly risking his own safety, only to discover that Jan Pekárek had some kind of an ulterior motive.

If that were not enough to consume his thoughts, Karl was also wondering what Prague would be like upon his arrival. The Prague of his memory reflected its rich history dating back more than a thousand years: buildings with gilded archways, concert halls where world-famous musicians had once performed, baroque statues, and tree-lined parks. That memory was interrupted with a vision of how Prague had been transformed by goose-stepping Nazi soldiers marching along banner-lined streets in a terrifying display of propaganda and pageantry. Karl had visited Czechoslovakia once briefly, when Phyllis had arranged a photo tour there in 1985. Despite the beauty that was still in evidence throughout the country, there were also noticeable signs of the oppression the country was enduring under Communist rule. Buildings were neglected and in disrepair. Goods of any kind were in short supply. The people looked solemn and disconsolate.

Phyllis had been encouraging and supportive when Karl had said good-bye to her in Istanbul earlier that morning. “You’re doing something wonderful for your family,” she had reminded him. “Your mother would be so proud,” she added, watching Karl pack his things at their hotel. At the same time, she couldn’t help but voice some concerns. “I’m worried about you being in Prague and doing something illegal.” At that, her eyes penetrated Karl’s, searching for reassurance, answers, anything to allay her fears. Karl returned her stare calmly.

“I won’t do anything foolish,” he had replied, though he wasn’t even certain what he would be doing. There was absolutely no blueprint for this trip, just a series of ideas and possibilities. He couldn’t confess this uncertainty to his wife. She was worried enough already. “And I will try to call you as often as I can, just to let you know I’m all right,” he had added reassuringly. He knew he wouldn’t be able to discuss much with Phyllis over the telephone. Everyone knew that phones in Prague were wiretapped, and anyone and everyone could be watched.

Phyllis tried to smile. “If it were up to me, I would never have tried to go after the paintings. I would have abandoned this plan from the start. But you were always the brave one – and persistent! You can’t let things go. I guess you have more of your mother in you than you think.”

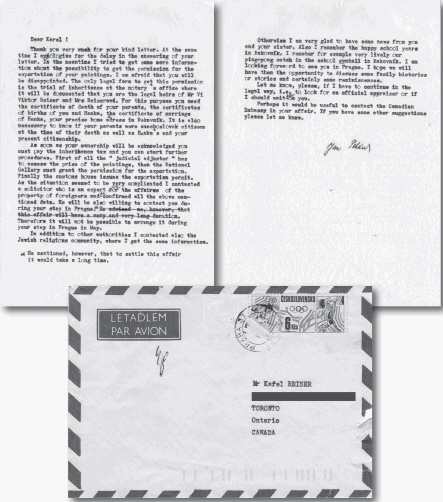

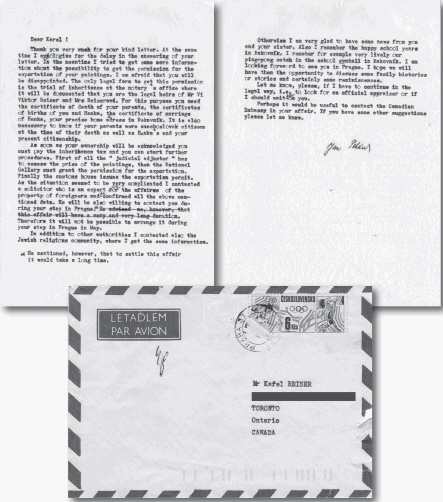

Those words echoed in Karl’s ears as his plane touched down in Zurich and he disembarked and headed for his hotel. A fax from his son, Ted, was waiting for him when he checked in. The reply letter from Jan Pekárek had arrived in Toronto after Karl and Phyllis had already left for Turkey. That was good news. It meant that Pekárek was still engaged in the process of trying to return the paintings. However, the letter did not contain the news that Karl had hoped to receive. In it, Mr. Pekárek acknowledged that he had begun to inquire about the procedures necessary to receive permission to export the paintings. He explained that it would have to be determined that Karl was the legal heir of Victor and Marie Reiser. Karl would have to produce death certificates for his parents along with birth certificates for himself and his sister. Documents were also required to prove that Victor and Marie were Czech citizens at the time of their death. That, in and of itself, could be enough to bring Karl’s efforts to retrieve the paintings to a grinding halt.

As soon as the legal ownership of the paintings was determined, a “judicial adjuster” would have to be appointed by the government to assess the value of the paintings. They would then impose a tax – a percentage of their assessed value – that Karl would have to pay. The National Gallery would then have to grant permission for the paintings to be exported. Finally, export permits would have to be issued by the customs department. The entire process was onerous and did not at all guarantee that, at the end of the day, Karl would receive authorization to have the paintings leave the country, even if he did meet the requirements and pay the tariff. Recognizing that the situation was complicated, Jan Pekárek stated that he had contacted a solicitor who was an expert on the “affairs of the property of foreigners.” This person had confirmed all of the stated requirements and had expressed his willingness to meet with Karl during his stay in Prague. He also warned that the process of settling the matter would be a long one – not something that was going to be completed in the short time that Karl was in Czechoslovakia.

As Karl read the fax, his heart began to sink. The conditions were overwhelming and daunting – simply impossible! Even if he were able to produce the required documentation, he knew that once this matter was in the hands of the Czech authorities there was little chance that they would actually release the paintings, particularly if the National Gallery assessed their value to be substantial. And Karl knew that the paintings were indeed valuable. He read the fax again, realizing that the prospect of reclaiming the paintings was slipping away. Given that Jan Pekárek had already begun a process of investigating the procedures necessary to export the artwork, Karl was more convinced than ever that the Czech authorities had already taken possession of them. It was even more disheartening that this news was reaching Karl on the eve of his departure from Zurich to Prague. Had he traveled all this way only to discover that his goal was unattainable?

As soon as he settled into his room, Karl picked up the telephone and called Ted in Toronto. Karl’s voice was tired and resigned as he voiced his concerns and apprehensions to his son. “I’m troubled by the whole matter,” Karl said. “There are at least a dozen obstacles facing me right now, and each one of them is complicated.”

“I agree,” said Ted. “But I’ve already contacted someone I know at the Department of External Affairs in Ottawa, a man named Lynch. He’s with the legal advisory division there.” Ted was typically practical and matter-of-fact, traits that Karl needed at this time. Doubts and misgivings would not service this project.

“I don’t trust the lawyer that Pekárek has contacted in Prague, notwithstanding his supposed expertise in foreign property affairs,” said Karl. For that matter, he did not trust anyone in Prague. Most people there had ties to the government, or, if they didn’t actively support the Communists, then they were likely under suspicion from them. Either way, this contact was unreliable. Both Ted and Karl agreed that the only way in which this plan had any possibility of succeeding was to seek legal advice from someone with the Canadian government.

“Mr. Lynch has suggested someone in his department who is an expert in dealing with estate matters in Eastern Europe,” Ted continued. “He’s willing to forward Pekárek’s letter to the Canadian embassy in Prague and see if the ambassador there can advise you in some way. After all, the embassy is there to look after the welfare of Canadians. Perhaps they would be willing to assist you in retrieving the paintings – without all the Communist nonsense and red tape.”

As Ted and Karl continued strategizing, Karl experienced a resurgence of hope. It was good to talk to his son, and energizing to brainstorm some ideas to move the plan forward. At the end of their conversation, Karl decided that he would personally contact the embassy and seek the counsel of the ambassador. “I’m going to try to make an appointment with him for when I’m there,” Karl said. “I need to meet with someone face-to-face and see if there is anyone who can really help me with this.”

“Your grandson is over eleven pounds,” Ted said as he and his father concluded their conversation. “That’s more than double his birth weight!”

Karl laughed. “Send him and Elizabeth my love,” he said, referring to Ted’s wife. “I’ll keep you posted on my progress here.”

As soon as he hung up, Karl dialed information to get the telephone number of the embassy in Prague. He was soon connected with the office of Chargé d’affaires Robert G. McRae. Keeping details to a minimum, Karl explained that he would be in Prague for a few days, and was requesting an appointment. A meeting was scheduled for May twenty-fourth at two o’clock.

Karl’s plane touched down in Prague and he collected his belongings and joined the line moving through passport control. It was long, and many ahead of him were being stopped and interrogated by the police. Karl checked and rechecked his papers; he could not afford for anything to go wrong at this point. When it was his turn, he handed over his documents and politely answered the questions about where he was from, and the purpose of his visit, silently giving thanks once more that the organizers of his high school reunion had inadvertently but conveniently planned the event for this time – a perfect reason to be entering the country. The border official scrutinized his passport and visa, and then scrupulously rummaged through his suitcase. Finally, he stamped Karl’s documents and waved him through the line.

During the taxi ride to his hotel Karl observed the city. Prague had suffered considerably less damage during the war than most other European cities in the region. But things had changed. The splendor of this city now lay hidden under a cloud of neglect. When the Communists had descended, Prague had plunged into disrepair. The once stately buildings that had been its landmarks, majestically towering over the streets and waterways, were now gray and aged, almost sagging under the layers of soot and dirt that had settled on them over the years. In place of fine architectural apartment buildings, the Communists had built tall, box-like concrete structures to house the people of the city, each one identical and uniformly drab. The citizens of Prague looked as worn down and dull as their surroundings. They walked quickly on overcrowded sidewalks, robotic, heads down, minding their own business. Broken-down motorbikes crawled along the congested streets, and were chased by dilapidated Škoda and Lada automobiles that spewed black exhaust from engines sputtering like rapid gunfire at every turn. There were no military officers, not uniformed ones at any rate, but Karl knew that the members of State Security were everywhere, spying on the movements of their citizens and their visitors. Karl’s frame of reference for the past fifty years had been the freedom of Toronto, and it was unsettling at first to think that he might be watched.

But there was something else that Karl knew about the situation in Prague. He was aware that the political system that had ruled so decisively for the last thirty years might actually be in decline. In recent years, the Soviet Union, long considered the primary enemy and rival of the West, was being regarded as less and less of a threat. The Soviet economy was floundering, and with it, its hold on its surrounding Communist-dominated countries. Shortly before Karl had left on this trip, there had been an article in the Toronto newspapers stating that Canada was calling for the release of Václav Havel, the renowned Czech playwright and dissident, who many were touting as the possible next president of a new democratic Czechoslovakia. Havel had been imprisoned for the last nine months for his part in demonstrations in Prague protesting the ongoing Soviet occupation. More and more protests of this kind were occurring on city streets across the country. And while the Soviets had quickly clamped down on these demonstrations, there was a sense that it was only a matter of time before the Communists would be forced to back down, or withdraw, and Czechoslovakia might once again claim its freedom from oppression.

It was against this backdrop of political entrenchment coupled with potential transformation that Karl arrived in Prague and proceeded to the InterContinental Hotel. He was surprised and impressed that the hotel had maintained its rather luxurious state. The first order of business after checking in was to call Jan Pekárek.

“It’s good to hear from you,” Pekárek said. “We must meet.” There were few details exchanged over the telephone. Pekárek’s voice was guarded and cautious. Karl could sense his anxiety and felt it as well. Both of them knew that someone could be listening in. “Please come to my place,” continued Pekárek. “We will talk.”

Karl took down the details, hung up the receiver, and headed outside to catch a cab. The warmth of the springtime air soaked through his light jacket and he squinted at the morning sun. He could hear the sound of the Vltava River flowing rapidly beneath the Charles Bridge, its waves lapping up against the break-wall. The scent of magnolia blossoms wafted through the air. Karl breathed in deeply and climbed into a cab. Despite the pleasant spring morning, he realized that he still bore the emotional scars of having fled this city for his life years earlier. Each corner was a reminder of those days in 1939: that street where Nazi soldiers patrolled; that bridge where Hitler had surveyed his troops; that park, once forbidden to Jews; that building that had flown the swastika. His breath quickened as his cab wove its way through the labyrinth of winding cobblestone streets, many too narrow for two cars to pass, before finally coming to a stop in front of a modest four-story apartment building.

He disembarked, glancing up. Jan Pekárek lived on the top floor and there was no elevator. After climbing the dark staircase, he reached the fourth floor and rang the doorbell. Pekárek opened the door and greeted Karl warmly.

“Please come in,” Pekárek said. “It’s good to meet you.” He stepped aside, and Karl entered a shabby but tidy apartment. He faced Pekárek and sized him up. The man was of medium build, rather pleasant looking, with thick, round, dark-rimmed glasses. He wore a tired old sweater and worn trousers. When he smiled, he showed his yellowed and crooked teeth, evidence of the country’s lack of adequate dental care.

Karl quickly learned that Pekárek was a medical doctor – an immunologist and a scientist of considerable reputation. He had written hundreds of research papers, which had been delivered in countries around the world, though sadly not by him. “This government would rather send a loyal comrade and Communist director abroad to represent the country, not a scientist like me. Foreign travel is a political reward here. My papers are the means to provide that to others.” Pekárek chain-smoked unfiltered cigarettes as the two of them sat talking. The ashtray in front of him overflowed with cigarette butts, and the smell of stale smoke hung in the air. Pekárek had been an enthusiastic Communist at one time. “But that was a long time ago,” he continued. “I’ve seen how this government has suppressed individual rights and abused civil liberties.”

His political journey had been a complicated one. During the Second World War, he had actively opposed the German fascists and had become an ardent Communist, even going so far as to join a group of partisan soldiers whose goal was to smuggle supplies to a group of saboteurs who were operating in the forests around Rakovník. He continued to be a vocal and passionate Communist after the war, supporting the country’s overthrow of President Beneš in 1948. Years later, he began to recognize the decline of cultural, social, and educational resources under Communist rule. And as he witnessed firsthand the restrictions on freedoms, he became disillusioned with his country’s political system and was now an outspoken critic.

“Mr. Pekárek, by speaking out, are you not afraid of arrest, or, at the very least, of losing your position at your research institute?” Karl asked. Pekárek was employed at one of the state-run laboratories in Prague. How did he have the courage to oppose the system so overtly and vocally, and particularly as he had a wife and young daughter? In this regime, even those who were related to, or associated with, dissidents could be blacklisted. The risk to his family was enormous.

Pekárek shrugged, and then answered matter-of-factly, “It seems that my position as a preeminent scientist has had some advantages. I’m quite simply irreplaceable. But please,” he continued. “I insist that you call me Jan. There is too much history between our families for such formalities.” It was a perfect opportunity to move the conversation to a discussion of the events of the war. “How did your family ever manage to get out of Czechoslovakia?” Jan asked. “I understand that it wasn’t possible for most Jewish people to leave once the war had started.”

“You’re right. It was virtually impossible,” Karl replied. “We left days before the official start of the war, and only because my father had connections out of the country, and my mother managed to pull together the necessary papers within the country.” He quickly filled Jan in on the details of their flight to freedom. “We were lucky,” he added. “Most of our friends and family members never made it out. They perished in Hitler’s gas chambers.”

The two men sat in silence. Karl wondered how much Jan really knew of the events of the war and the suffering of Jewish citizens in Czechoslovakia and elsewhere. He was Hana’s age, and would have been a young teenager then, living in a rural town, raised in a milieu of latent anti-Semitism and then overt persecution of Jews. Those events would have been the norm for Jan. Furthermore, after the war, he had lived within the confines of Communism, and his life had been impacted more by those circumstances than by the events of the Holocaust. Besides, even today, most Jews living in Czechoslovakia still kept their Jewish identify a secret.

“Tell me how your sister is?” Jan broke into Karl’s thoughts.

“She’s well, thank you. She’s married and has three children and several grandchildren. She and her husband live in Toronto, not far from my wife and myself.”

“And your mother – I was sorry to hear of her passing. I didn’t know her, but I can tell from the documentation regarding the paintings that she must have been a strong woman.”

Here was the opening that Karl was waiting for, a chance to talk about the paintings. “Yes, my mother was indeed passionate,” he said as he leaned forward. “You mentioned in your letter that you had found some documentation. My mother spoke very little about this after she returned to Toronto in 1948, except to say that she had not been able to recover the paintings.” He knew he was skirting some of the facts. After all, in Karl’s mind it was due to the greed of this man’s grandfather that Marie had failed to reclaim her property. But Jan had expressed his willingness to return the paintings, and Karl was being careful not to offend him.

Jan stood and walked over to a large wooden desk in the corner of his apartment. He rummaged through a stack of file folders, retrieved some papers, and returned to sit next to Karl. “These are the letters I found amongst my grandfather’s belongings after he and my father had died.”

Karl took the papers and quickly read through them. There they were: the letter affirming that the four paintings belonged to Victor and Marie, along with letters from Marie to Alois Jirák’s attorney demanding the return of the artwork, and Jirák’s refusal to do so. It was all there in front of him, the evidence of the unpleasant exchange that must have taken place between the two parties. He looked up at Jan, unable to speak.

“Take them and get some copies made,” Jan said. “I would like the originals back.” He seemed unperturbed by the documentation that implicated his grandfather in this way. “It was so helpful to see this material in writing. That’s what led me to your family after my grandfather died.”

Karl nodded, folded the papers, and put them inside his jacket. “I gather from your letters that it will be difficult if not impossible to get the paintings out of the country.” Karl was still fighting to calm his beating heart. He felt the need to steer the conversation away from their family feud, and to discuss the current status of the paintings.

“Yes, I’ve made inquiries, and the regulations are impossible to say the least.” Jan proceeded to outline the conditions that he had previously listed in his letter to Karl.

Karl hung his head. “My mother dreamed of bringing the paintings to Canada. I just can’t accept that there isn’t a way to fulfill her wish.” Once again, it felt as if he had come to a dead end as far as his family’s treasures were concerned.

“Would you like to see them?” Jan asked. Karl looked up puzzled. “The paintings,” Jan repeated, “would you like to see them?”

“Of course I would,” Karl replied. He had not even dared to ask this question. Surely by now the paintings were in the hands of the authorities who had come to collect them following Jan’s inquiries. But perhaps Jan still had access to them. “Can you arrange for me to look at them?” asked Karl. “Where are they?”

Jan smiled. “Come with me,” he said. “I’ll show them to you.“

The second letter that Jan Pckárck wrote to Karl outlining the procedures he would need to follow in order to export the paintings from Prague.