Castle and was still extracting notes and binders from his briefcase. As soon as VandenBosch sat down, McRae put aside his papers, perched himself on the edge of his desk, and waited expectantly.

Castle and was still extracting notes and binders from his briefcase. As soon as VandenBosch sat down, McRae put aside his papers, perched himself on the edge of his desk, and waited expectantly.Prague, May 1989

SHORTLY AFTER Karl left his office, Richard VandenBosch headed down the hallway to meet with Robert McRae. He knocked softly on his door and entered, sinking heavily into an armchair across from his desk.

“How was the appointment with Mr. Reeser?” McRae asked. He had just returned from his meeting at the  Castle and was still extracting notes and binders from his briefcase. As soon as VandenBosch sat down, McRae put aside his papers, perched himself on the edge of his desk, and waited expectantly.

Castle and was still extracting notes and binders from his briefcase. As soon as VandenBosch sat down, McRae put aside his papers, perched himself on the edge of his desk, and waited expectantly.

“Incredible!” Richard replied. “I need to talk to you about this.” McRae was not only Richard VandenBosch’s superior, but had become a valued friend over the years. They had met while posted together in Yugoslavia. It was McRae who had recommended him for the position here. Richard respected and often sought out McRae’s advice. “This man’s story – his life – is quite remarkable,” he continued. Just as Karl had done for him, he unfolded the history of the paintings. “Mr. Reeser wants the embassy to take possession of the paintings while he figures out a way to get them out of the country,” he went on. “If he goes through the ‘legal’ channels, you and I both know that they will be confiscated. Housing them here will give him time to figure out a better plan.”

McRae nodded thoughtfully. “And what did you tell him?”

“I said we’d have no problem with that.”

McRae nodded again but did not reply. The calm and acumen he possessed came from years of having worked in diplomatic service. Robert McRae had seen and heard it all.

“As far as I’m concerned, the paintings are the property of a Canadian citizen,” Richard continued. “The letter we have from this Jan Pekárek proves that. That makes the artwork Canadian as well. I don’t care how long it’s been here in this country.” He leaned forward in his chair to face McRae. “Look, there’s no way we should let the Communists get their hands on this stuff. Our job is to help Canadians in need, and this guy is desperate for our help.”

It was no secret that Richard VandenBosch had little fondness for the government of the day. He had witnessed firsthand the repressive activities of the police and had seen the impact they had on the people of this country. Over the nearly two years that he had been here, his emotions had turned from sadness for the country, to irritation, and then to outright anger. He was tired of the crude campaign of harassment carried out under the guise of conducting government business. He sometimes wondered what the authorities thought they might uncover with this constant scrutiny, but he also knew that it was the very act of surveillance that kept the citizens cowering and on guard.

He had also had personal experiences of being watched and spied upon, notwithstanding his diplomatic immunity, which was meant to protect him from interference or intimidation by a host government. Most days, he could look out the window of his office and see the barely concealed undercover agents, training their long-lens cameras on the embassy building. He had answered telephone calls in the middle of the night where no one would reply on the other end, and he knew that his phone had been bugged.

There had even been a time, the previous summer, when he and a group of diplomatic families had all gone out for a weekend picnic. Twelve cars with diplomatic license plates headed out of the city toward a spot in the countryside. Richard had his wife, Anne, and his two young sons, Alexander and James, in the car with him. They eagerly anticipated spending a relaxed afternoon in the fresh air and away from their small, dank apartment where there was always a taste of burning coal in the back of their throats.

The families had found the perfect spot in a small valley where green fields dotted with daisies butted up against gently rolling hills. They had parked their cars, spread blankets on the grass, and pulled out baskets of sandwiches, sweet cakes, and beer for the adults. The children had begun kicking a soccer ball around the open field. But in the distance, on a sloping hill and clearly visible to all, a line of black cars was also parked. A half a dozen or more plain-clothed agents were standing in front of their automobiles, binoculars and long-range cameras aimed directly at the embassy families below. Big Brother was always watching.

Now that there was a sense of change in the political landscape of Czechoslovakia, the demands on the Canadian embassy to assist people had increased dramatically. Recently, people had been escaping from East Germany and were coming through Prague to get to the embassy in West Germany. Cars were being abandoned in the city as people tried to flee. Tents had sprung up in the gardens of public buildings, housing families who were desperate to get papers to go overseas. No one really knew what would happen to the citizens of Czechoslovakia if the Iron Curtain collapsed. And no one could predict what would become of personal property.

“I don’t like people getting ripped off,” he continued, springing from the armchair in McRae’s office and beginning to pace back and forth. He hadn’t even seen the paintings, but was already drawn in by Karl’s vivid description of them. “They’ll be sold, and some corrupt Communist is going to pocket the cash. Or they’ll end up on some party official’s wall, someone who will never know or care about them, or the blood, sweat, and tears it took to get this family out of the country during the war.”

VandenBosch had listened to many stories over the years. But this one, Karl’s story, had something more. It was the fact that his family had miraculously escaped unscathed in 1939, when so many other Jewish families had met a devastating fate. It was the injustice of having entrusted valuables to someone, only to have that person betray that trust. And it was the miracle of discovering their goods still safe here in Prague, and yet still unattainable.

He finished pacing and faced McRae. “This family defied the odds by getting out of here before the war,” he said. “Now it’s time to reunite them with what is rightfully theirs.” He sank back down into the armchair and waited for McRae’s response. But he was not worried. He and the chargé d’affaires were like-minded civil servants. They shared the same concern for the welfare of Canadians in need, and both were equally determined to right the wrongs committed against fellow nationals.

“I’m with you on this one,” McRae replied. “Let’s see what we can do.”

The two officials sat down to formulate plans. Richard would accompany Karl to retrieve the paintings and the two of them would transport them in a diplomatic vehicle to the embassy. The diplomatic car would provide immunity, ensuring that they would not be stopped or searched during the transfer. McRae agreed that this all had to happen on Saturday, two days later, when the workers doing renovations in the building were off. “If we’re going to do this, then let’s do it with as few eyes on us as possible.”

Richard nodded. “I’m just waiting for Mr. Reeser to confirm things from his end, and then we’re all set,” he concluded.

“As I said, I support this one hundred percent,” said McRae. “But we should probably discuss what might happen if the Communists do get wind of this plan.”

VandenBosch shrugged. Of course he had considered this possibility already, and knew there could be consequences for the embassy if it colluded in a scheme that defied the protocols of its host country. At the very least, this could be embarrassing for the embassy. At worst, it could have international implications.

“If they find out, I suppose I could be thrown out of the country for contributing to the theft of what they consider to be their property,” Richard said. “That certainly wouldn’t look good on me or our country. But I’d fight any suggestion that we’re breaking the law,” he added. “As far as I’m concerned the paintings are Canadian, and we are perfectly within our rights to help Mr. Reeser get them out.” He would not be intimidated by the possibility of this plan being discovered. And even if the Communists found out what the embassy was doing, at the end of the day, he knew that he was protected by the rules of the Geneva Convention, providing him immunity from prosecution. His personal safety would not be compromised.

“I know you’re a passionate man. But just promise me you won’t be a cowboy, okay?” McRae stood to signal the end of the meeting. VandenBosch smiled. It was in his nature to fight for the underdog, and this case would be no exception. “I need to brief the ambassador on all of this, just to be on the safe side,” added McRae. “But I think he’ll agree with everything we’ve decided. Let me know when Mr. Reeser confirms things. By the way, I’m looking forward to seeing those paintings myself.”

When Karl left Richard VandenBosch’s office, he headed straight back to his hotel and immediately placed a telephone call to Jan Pekárek. Keeping the discussion brief, he arranged to meet Jan and his wife for dinner the next evening. It would be easier and safer to have a discussion about the plans in a public place, rather than over the telephone. Next, he placed a call to Phyllis. Again, it was difficult to have the full conversation he yearned to have with his wife.

“How is everything?” she asked. Karl could hear the veiled anxiety behind her simple question.

“Things are going well,” he replied, deliberately trying to keep his voice light and even. “Moving forward, in fact.” There was so little he felt comfortable saying. Throughout the call, he waited and listened for the click to indicate that the line was being tapped. But he did want to reassure Phyllis that he was safe.

“I can’t wait for you to be home,” Phyllis said.

“Only a few more days. Don’t worry,” he added. “Prague seems to be looking better than ever right now.” He chuckled to himself, wondering if Phyllis would guess what he meant by that oblique statement. “I’ll tell you all about it when I’m home. Love to you and the children.”

When he got off the telephone, there was a call waiting for him from Richard VandenBosch. Anxiously, Karl returned the call.

“We’re all set here,” the jubilant voice of Richard VandenBosch boomed over the telephone, immediately allaying the fears that had crept into Karl’s mind. This call signaled to him that all of the authority figures at the embassy were on board with the plan. “Can you meet me here Saturday morning, as we discussed?” he asked.

Karl took a deep breath. “I’m having dinner with my friend, tomorrow evening.” He was deliberately vague about naming Jan on the telephone. “If you don’t hear from me, then you can assume that I will be there first thing Saturday morning.”

“I’m looking forward to seeing you then,” Richard replied and the two men said their good-byes.

The next evening, Karl caught a cab to the Hotel Paris where he was to meet Jan Pekárek for dinner. He entered the formal lobby and was once again overwhelmed with nostalgia for this once fine establishment. His father had been a regular guest of this hotel on his business trips to Prague. And while he and his mother and Hana had lived in Prague after escaping Rakovník, this hotel was also the place where Marie had made her telephone calls to Victor in France. She had parked herself in a private telephone booth in this lobby, anxiously awaiting his calls, filling him in on the details of her attempts to secure their travel documents, and trying, unsuccessfully at times, to sound strong and dispel his fears for the safety of his family. At each step Karl felt that he was following in the path of his mother.

Despite the shortages and the general shabbiness of the city, the Hotel Paris restaurant was still quite elegant and bustling with activity. A familiar Czech folk song played softly through overhead speakers. Karl was led to a quiet table in a corner of the room. He was early for the dinner meeting, and, while awaiting the arrival of Jan and his wife, he composed himself, concentrating on the details that he needed to have in place for Saturday. Even though things were far from resolved as far as getting the paintings out of the country, Karl already felt lighter knowing that he would be able to move them to the embassy.

Karl rose from his seat as Jan entered the restaurant, right on time. He waved, and Jan and his wife moved toward the table. Karl was introduced to Jan’s wife. She smiled, accepting Karl’s outstretched hand, as he invited them both to sit. He was anxious to talk about the paintings, but decided they should first order and enjoy their dinner. The meal was classic Czech fare, not unlike the meals Karl remembered from his childhood – beef with dumplings and thick brown gravy, and sweet and sour pickled cucumbers on the side. They washed all of this down with several glasses of local beer. The conversation with Jan was light. They discussed Karl’s life in Toronto and Jan’s work at the lab. His wife, a pleasant-looking woman, was largely silent, drifting into the background of their discussion and seeming somewhat subjugated by her husband’s obvious intellect. It was only after the three of them had received their coffee and dessert that Karl and Jan finally put their heads together to talk about the plans for the paintings.

“I’ve made arrangements to move the paintings from your home to the Canadian embassy,” began Karl, glancing around. The waiters had moved back from their table to a respectable distance. Still, he lowered his voice. Briefly, Karl reviewed his meeting with Richard VandenBosch and told Jan of the embassy agreement to temporarily accept custody of the paintings.

“So you’ve decided not to go through conventional channels,” Jan interrupted at one point.

Karl nodded. “I won’t do anything that jeopardizes your safety,” he added. “You have my word on that.”

Jan looked thoughtful. “It’s probably a wise decision to bypass the government,” he said after a short pause. After that, he asked few questions. It was not necessary to know too much, simply the part that he would have to play in all of this. His wife was silent, glancing periodically at her husband and listening closely to what was being said. “I’d like to come for the paintings tomorrow, Saturday morning,” Karl concluded.

Jan, who had been nodding at everything Karl had said, frowned unexpectedly and lowered his gaze. Karl was instantly ill at ease. Had Jan changed his mind? Would he refuse to relinquish the paintings? Everything hinged on this part of the plan. Karl stared at Jan, waiting for him to speak. But Jan was not backing out.

“There’s a man in our apartment building – an administrator,” Jan began anxiously. “Every building has one.” At that moment, a waiter moved toward the table to refill coffee cups, abruptly silencing the conversation. Only when the waiter had finished pouring and moved away did Jan lean forward and resume speaking. “We must be careful when this administrator is there. He watches everything, everyone. That’s his job, and if anything out of the ordinary were to happen, he’d be the first to report it.”

Another tense moment passed.

“He’s a party appointee. He’s meant to let the Communists know about the business of each and every tenant, particularly those activities that are suspicious or out of the ordinary.” Jan leaned even closer and lowered his voice to a whisper. “We could never chance moving something as large and obvious as the paintings with him in the building. He would report us in a moment.”

Karl exhaled deeply and closed his eyes.

“This man goes out to work during the week. That’s when no one is around to watch the tenants, and we’d be freer to move about,” Jan continued. “But on evenings and weekends, this fellow is home. We simply could not be seen moving anything on a Saturday. I think it would be better to move the paintings on a weekday. Would that be possible?”

Karl’s heart sank. The one day that the paintings could safely be moved into the embassy was the one day that they were at risk of being discovered in Jan’s home. “No!” he replied. “A weekday is impossible. The embassy is undergoing renovations, and workers are crawling all over that building like ants. They’re all watchdogs according to my contact there.” He thumped his fist on the table, at once irritated and frustrated with the circumstances. “How do you live under this toxic microscope?”

The question, unanswerable, hung in the air and Jan shrugged his shoulders and looked away. In that moment, his wife reached out unexpectedly to touch his arm. She whispered something to him. He nodded, and then turned back to Karl. “There is one slight chance,” Jan said. “This fellow, the informer, has a cottage in the country. He often spends his weekends there, unless his wife is working in town. She occasionally moonlights as a cloakroom attendant in one of the museums. You’ll have to call me early tomorrow morning. I won’t know his plans until then. With luck, the weather will be good, and he and his wife will decide to leave for the weekend.”

Karl nodded. It was all he could do for now. He wished that he could leave this dinner meeting with the moving plans firmly in place. But that was not to be. Karl and his dinner guests finished their coffee, said their good-byes, and left the restaurant.

He spent another restless night at his hotel; his sleep was constantly interrupted with thoughts of the paintings. At one point, the telephone rang shrilly, the sound cutting through the silent shadows in Karl’s room. He groped for the receiver, but when he put it to his ear, no one was there. It must have been a wrong number, he reasoned, as he replaced the telephone and lay back down on his pillow. But was it as simple as that? Or was he now the target of some investigation by police agents?

Would he be able to safely move the paintings to the embassy? He imagined himself being stopped outside Jan’s apartment door, the paintings in hand, secret police surrounding him. The paintings would be confiscated, but what of him? Would he be arrested? Expelled from the country? The paranoia in Czechoslovakia choked you, Karl thought, worse than the pollution in the air, or the smoke that hung in the restaurants and bars. He turned over in bed and tried to close his eyes to the fear.

Early the next morning, Karl picked up the telephone. Holding his breath, he dialed Jan’s number.

“We’re in luck,” Jan said as he answered the phone. The coast was dear. The informer had gone to his cottage for the weekend. The plan was on.

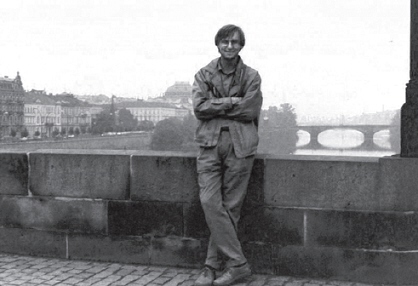

Richard VandenBosch on the Charles Bridge, while stationed in Prague, 1989.