N 1

1

Transportation for Hire

From Human Burden to Taxis

THE EARLIEST HUMAN TRAVEL WAS SELF-LOCOMOTION. Mankind was blessed with very strong legs, and we could transport ourselves over very long distances. These day-by-day perambulations could carry one across a continent, if such a long trip was necessary. The average person can complete between 20 and 25 miles in a day, with the actual walking time totaling only six to eight hours. Someone who was determined to cover more ground could walk for a few more hours and do 30 miles in a day. Hence crossing North America could be done on foot in a little less than three and a half months. This optimistic schedule would depend on favorable weather, a certain degree of good fortune, and no unforeseen difficulties. In reality, however, when we consider crossing the country's several mountain ranges and rivers, which would impede travel considerably, it would likely take twice as many days to march across the vast expanse of what is now the United States. Most early travel was actually more local in nature and involved the search for food when our ancestors subsisted as hunters and gatherers of cereals, fruit, and small game.

1.1. Tunis bearer and passenger, ca. 1890.

(Marshall M. Kirkman, Classical Portfolio of Primitive Carriers, 1895)

With the establishment of agriculture about ten thousand years ago, mankind settled down into a less ambulatory lifestyle. Walking remained the chief mode of getting around, until the domestication of animals opened a new era in travel. The donkey proved itself a reliable, if slow-moving, beast of burden. The introduction of the riding horse from Central Asia in about 1400 BC offered Europeans the first really fast way of getting around. Speeds of 25 mph could be reached, but the animal could sustain such velocities for only very short distances.

Every community included certain members who were unable to walk very far because of advanced age, physical disabilities, or illness. For these same reasons, they could not stay on horseback for long. A few were simply too lazy to do so, but if they had the means they could hire a human bearer to carry them. A few strong men in need of money were ready to hoist people up on their back and march out to wherever their patrons cared to go. It can be assumed that most such journeys were relatively short. This practice continued in certain parts of the world until late in the nineteenth century. Marshall M. Kirkman included engravings of human burden bearers in his 1895 volume on primitive carriers. He shows such a carrier in Tunis and a second example from Turkey (figs. 1.1 and 1.2). Figure 1.2 shows a Turkish human bearer fitted with a folding chair strapped to his back. The passengers sit facing backward on the seat. The rear legs of the chair are inserted into sockets on the bearer's trousers. The passenger has a foot rest, a sun shield, and a wraparound handrail. In a similar fashion, ferrymen would carry patrons across creeks and small rivers piggyback style. This practice goes back to ancient times, for Saint Christopher was a human-bearer ferryman in Syria in the third century AD. After his martyrdom in about 250 AD, he became a hero to early Christians. Many centuries later he was canonized as the patron saint of travelers and ferrymen. However, his feast day, July 25, is no longer celebrated by the Roman Catholic Church. Figure 1.3 shows ferrymen in Formosa carrying patrons across a shallow river in the 1890s.

1.2. Turkish bearer and passenger, ca. 1890.

(Marshall M. Kirkman, Classical Portfolio of Primitive Carriers, 1895)

1.3. Ferrymen in Formosa, ca. 1890.

(Marshall M. Kirkman, Classical Portfolio of Primitive Carriers, 1895)

One-on-one transport surely had its limitations, especially if the passenger was very large, the trip very long, or the terrain very difficult. The use of a portable bed allowed two or more men to transport a single passenger for longer distances with greater ease, since the burden was divided among multiple bearers. The bed was similar to a modern stretcher, as the frame extended beyond the limits of the bed itself. The use of removable poles attached to the frame's sides worked even better. If the poles were made long enough, up to eight men could serve as bearers. A lightweight compartment was made by adding upright posts, a roof, and draw curtains at the sides and ends. The curtains kept out sun and offered the occupant a degree of privacy. Conveyances of this type are believed to have originated in Asia. The Greeks adopted them for invalids and women, but in general the litter was not fashionable for regular travel. It became so in Rome around 190 BC. The Romans called them lectica, the Latin word for “bed.” A soft mattress and bolster, plus easy pillows, added to the traveler's comfort. The more luxurious litters were made from precious woods and decorated with ivory, silver, and gold. The curtains were fashioned from the most costly textiles (fig. 1.4). Less ornamental litters could be found near the city gates of most towns. They were available for hire by anyone who could pay the fare and represented about the only form of public transit available in ancient times. The remains of one of these simple litters were discovered in Rome on Esquiline Hill in 1874, offering the best record yet found for such a conveyance.

1.4. A Roman litter, or lectica.

(Johann Christian Ginzrot, Die wagen und fahrwerke der Griechen und Römer und anderer alten Völker, Lentner, 1817)

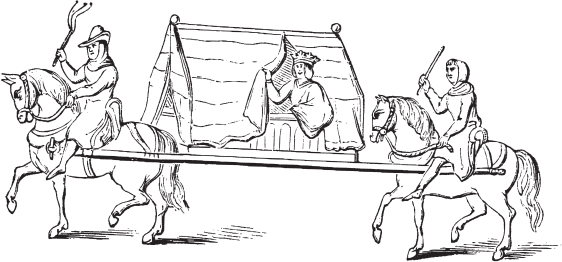

For longer journeys, litters were slung between two mules in a fore and aft position. The compartment was somewhat more substantial than the litters carried by human bearers. An attendant walked beside the basterna, as such conveyances were named in Roman times, to guide and manage the mules. Riders or postilions, one on each mule, were sometimes used in place of the walking attendant. If nighttime travel was attempted, torch bearers walked ahead to light the way. Figure 1.5 shows an illustration of a French horse litter of the fourteenth century.

A chair fitted with two horizontal poles allowed two men to carry a passenger. It also offered the passenger a more comfortable ride. Where labor was cheap, the use of two rather than one bearer made little difference in the operating cost. Just when and where the traveling chair was introduced cannot be determined, but they were used by all societies. In Madagascar four rather than two bearers were employed. The poles were carried on the men's shoulders – Asian style – rather than at waist level, which was typical in the west.

The chair was improved during the 1500s by a lightweight enclosure as the sedan chair. Italy was the apparent home of this improved form of chair, and the name likely comes from the Latin word sedes, meaning “to sit.” The compartment was large enough for only one occupant and measured about 30 by 30 by 60 inches. The enclosure offered privacy to the traveler and protection from the sun and rain. The entrance door was placed at the front of the enclosure. The sedan chair spread from Italy to Spain and finally to England in the late sixteenth century. After 1630, sedans were commonly used in London as taxis. During the eighteenth century they were frequently used by ladies and gentlemen in the cities of England and France for transportation. During Queen Anne's reign the fare was fixed at 1 shilling per mile. Wealthy families might own their own sedan, often handsomely painted by a notable artist. The exteriors were decorated with gilt and fine carvings. The interiors were lined with silk, and the bearers wore elegant uniforms.

1.5. A French horse litter, or basterna, fourteenth century.

(Ezra M. Stratton, The World on Wheels, 1878)

The sedan chair was used to a more limited degree in the major cities of North America in colonial times. In 1770 Philadelphia was the largest city, yet its population was only twenty-eight thousand. Ben Franklin mentions riding in a sedan chair nineteen years later. Efforts to introduce this form of city transit in Boston were less successful. The Puritans found the very idea abhorrent. A remarkably elaborate chair, covered in costly silk and festooned with solid silver ornamentation, was offered to John Winthrop (1588–1649), the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It had been found on a Spanish galleon captured off the coast of Mexico. Its Yankee capturers thought the governor would be delighted to receive this glittering prize, but the frosty old Winthrop snorted that he had no need for such a frivolous thing.

The sedan chair was put on wheels sometime later in the eighteenth century by French carriage makers. How widely used such vehicles became is uncertain. The vehicle's body was considerably larger than the typical sedan chair, big enough possibly for two passengers. It rode on spoke wheels about 4 feet in diameter. A single man pulled it along using a pair of shafts attached to either side of the body. This vehicle was actually nearly identical to rickshaws once used in Asia and Africa except for its enclosed body. They were called vinaigrettes because of their resemblance to bottles of smelling salts once so popular in genteel households.

1.6. A sedan chair, eighteenth century.

(Thomas A. Croal, ed., A Book about Traveling: Past and Present, 1877)

INTRODUCTION OF THE TAXI CAB

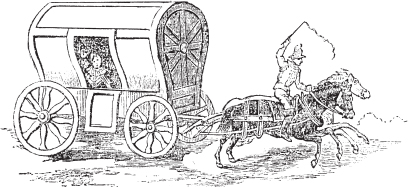

The ancient ancestor of the modern taxicab can also be traced back to water taxis on the River Nile in the time of the pharaohs. Similar services were offered on the Thames from London Tower and upriver to what is now London's West End in Shakespeare's time. Imperial Rome offered hackney service using a four-wheeled carriage invented by the Gauls called the rheda, or redae or reda. It sometimes had a cloth roof to fend off the sun or rain and was generally powered by a team of oxen (fig. 1.8). These sturdy beasts were slow but steady and were not so easily fatigued as horses nor as likely to run amok. Figure 1.8 is likely a more pristine example of a rheda while still in like-new condition. In about 1625, horse-drawn vehicles called hackney coaches appeared on London's streets that offered to carry city dwellers around town for a modest fee (fig. 1.9). These for-hire carriages were generally elderly, unkempt, and rather soiled. Some of these same vehicles had once been elegant showpieces belonging to a royal family. But now they were near the end of their service life. The drivers were of a similar unsavory nature. Worse yet, they tended to be rude, drunken, and inclined to overcharge their patrons whenever possible. Because some hackmen drove in a fast and reckless fashion, they were called “Jehu” after the Tenth King of Israel, Jehu (d. 816 BC), who drove his chariot in a fury against the king of Judah. Even so, they offered ready transport when most people needed to – and could, if the occasion demanded it – fly across town like frightened rabbits.

1.7. A British sedan chair with a lift-up roof, eighteenth century.

(Author's collection)

The word hackney is said to have come from a medium-size riding horse with an ambling gait that was once popular in England. While too small for hunting or military use, the hackney proved suitable for pulling light vehicles. Other etymologists contend the term comes from the word hack, which meant any article for sale or hire. The driver of the first hacks rode on the back of the horse as postilions rather than on the vehicle. Hackney was often shortened to hack and came to mean any overworked horse. Indeed the word hackneyed, connoting an overworked phrase or saying, comes from the same source. It is also claimed that the name is derived from a borough situated about 3.5 miles northeast of the London Bridge, but most etymologists deny this theory.

1.8. A Roman rheda used for both private and taxi service.

(Ezra M. Stratton, The World on Wheels, 1878)

The growing popularity of the public coaches alarmed Charles I, who felt they were damaging the city roads and thus diverting public money that might be better spent maintaining his royal court in greater luxury. In 1635 Charles ordered that their number be limited to fifty and that the hackneys be licensed and regulated, not so much to protect the public as to discourage their use. London was growing so fast, however, that traffic congestion and an increasing number of people created a greater demand for improved urban transit. London was becoming the largest city in world – between 1600 and 1700 it grew from 200,000 to 675,000 residents – and the number of hackneys grew with the population. By 1662 there were 500 hackneys in the British capital. In 1694 the count was up to 700, and by 1771 there were 1,000 in service. The hackneys might be shabby in appearance, but they were a fast way to get around for those who could afford to pay. Fares varied over the years, from 3V2 pence per mile to a zone fare system set up inside a 4-mile circle with Charing Cross at its center. Within the circle a flat fare of 1 shilling prevailed; outside the circle the rate was 1 shilling per mile or fraction of a mile beyond the first. Drivers were allowed to charge a small fee for luggage as well. The coaches were governed by laws going back to the time of Richard I's first year as king, 1189, when ferrymen, innkeepers, and flour mill operators became the subject of standards of service and price regulations. This became part of British common law that was copied in the American colonies of today's United States. The hacks faced increasing regulations in the Victorian era. In 1843 the London Hackney Act required drivers to wear badges and to refrain from using profane language, driving too fast, drinking on the job, and overcharging their passengers. Their vehicles were subject to annual vehicle inspections. The drivers were tested for driving skills and an expert knowledge of the city street system. They were required to display lighted lamps at dusk and during the dark of night. This law became the model for other cities around the world.

1.9. An English hackney wagon of about 1650.

(Author's collection)

Yet nothing seemed to discourage the growth of the taxi fleet. By 1860 there were more than forty-three hundred hacks operating in London. Early in the next century, the number grew to over eleven thousand. The rustic old hackney coach had long since passed out of fashion by this time and had been replaced by specialized vehicles designed and built specifically for taxi service.

The first of this new breed appeared in London in 1823. It was a light, springy, two-wheel carriage called the cabriolet that had been popular in Paris since the early 1700s (figs. 1.10 and 1.11). It required only a single horse, which made it far more economic than the heavy hackney coaches, which needed two horses. The cabriolet could turn and maneuver easily in traffic, swinging around and dashing off in the opposite direction with ease. Its name came from a Latin root word for a young goat or kid that had a frisky, capering motion to it. The passenger seat was covered by a fold-down top that could be raised or lowered according to the weather. Waterproof curtains could be closed to protect the occupants on rainy days. The driver sat on the right side of the body, on an outrigger seat, with no protection from the elements. The harness of these lightweight taxis often had small bells attached that set up a jolly serenade as the cabriolet bounced along the streets. By mid-century four-wheel cabriolets were introduced. The name was quickly shortened to “cab” and so has come into modern usage.

In 1834 a Leicestershire architect named Joseph A. Hansom (1803–1882) patented a unique style of carriage for taxi service. It featured two very large wheels, a narrow boxlike body with two side-by-side seats and a low front-door passenger entrance. The driver sat on a roof above the passengers. A test vehicle was driven around the streets of London. Hansom offered rights to his design for £10,000, but no buyer came forward until John Chapman, secretary of the Safety Cabriolet and Two-Wheel Carriage Company, secured right to the patent for a small fraction of Hansom's asking price. Chapman improved the design by moving the driver's seat behind the passenger compartment for better balance and devised a lever system to open and close butterfly doors on the front of this enclosure (figs. 1.12 and 1.13). The Hansom cab proved a success as modified and became the “gondola of London.” Later in the nineteenth century it was popular in New York as well. Munsey's magazine claimed in June 1898 that the Hansom had captured New York. They were as thick on Fifth Avenue as in Piccadilly. The whole avenue was alive with them. For reasons not explained, the Hansom was the joy of the feminine heart.

1.10. A British cabriolet of the 1820s.

(H. C. Moore, Omnibuses and Cabs: Their Origin and History, 1902)

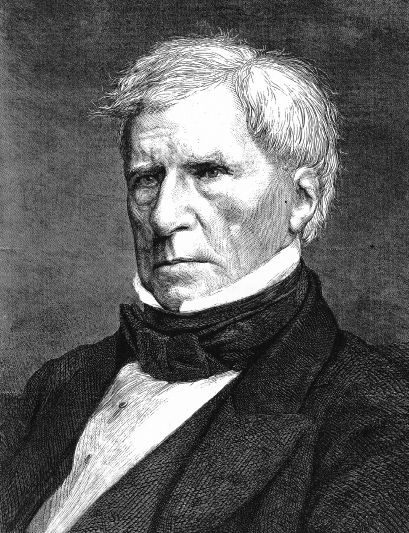

Not long after the introduction of the Hansom, a prominent Scottish jurist, Henry P. Brougham (1778–1868), became interested in carriage design. How this very busy lord of the realm found time for such a trivial occupation is difficult to imagine, for he was a Member of Parliament, Lord Chancellor, and the founder of London University (fig. 1.14). Yet in 1838 Lord Brougham's contribution to the betterment of horse-drawn transport was unveiled (fig. 1.15). It was a light four-wheel vehicle with a drop floor, making entry and exit safe and easy. The driver sat out front on an open seat. The passenger compartment seated two comfortably.

1.11. An American cabriolet of about 1830.

(Ezra M. Stratton, The World on Wheels, 1878)

A third passenger could ride right up front with the driver – this was a favored place for young boys. Brougham had intended it as a gentleman's carriage, yet it had features that recommended it for hack service. It was described as discreet, simple, practical, and dignified. It was the most popular closed carriage in Victorian England. Ease of access and a better ride because of the four wheels made it a strong competitor to the Hansom, and many a London cab was soon built to Lord Brougham's plan. It, too, traveled across the Atlantic to find favor in New York City among taxicab operators.

THE TAXICAB APPEARS IN THE NEW WORLD

It is likely that cab service originated in the United States in March 1840. By mid-April of that year, twenty-five such vehicles were operating in Manhattan. A watercolor rendering of one of these two-wheel conveyances was prepared by a contemporary Italian artist, Nicolino Calyo (1799–1884), who prepared a series of paintings based on New York street scenes. The cab was very similar to Hansom's design, except that the wheels were smaller and the entrance was made through a rear door. By 1866 there were approximately fifteen hundred cabs in this great city near the sea. Leslie’s magazine, in its issue of January 6, 1866, offered an appraisal of the local service and found much to critique. The light and handy cabs of the 1840s had been replaced by lumbering secondhand coaches that were slow and clumsy. They were manned by “one of the most insolent sets of men in the city.” Two horses were needed, and the seating for four to six was wasteful. Most cab patrons traveled alone and hardly required such ponderous vehicles. Passengers were ready to pay for fast, courteous service, yet the New York system charged high for the rather sluggish travel. Leslie’s editor went on to note the contrast between taxi operation in New York with those of its European counterparts. New York cabs charged 50 cents for short trips plus 25 cents for each additional passenger. London fares were fixed at 18 U.S. cents a mile or 72 cents per hour. Things were cheaper yet in Paris, where the 6-mile-circle zone fare was just 37 U.S. cents or 60 cents per hour. Both London and Paris had small and nimble vehicles that could thread their way quickly through the worst traffic. When would New York catch up with the great cities of Europe?

1.12. A Hansom cab of 1898.

(The Hub, August 1898)

There was a gradual shift to Hansom cabs, but the old flat-rate fare of 50 cents remained in place until the early twentieth century. Some years earlier the 1871 Scientific American noted that Manhattan cabs were painted dark red and striped in broad vermillion lines and thin black lines. Some details on cab operations were given in Outing Magazine of November 1906. It noted that the two thousand taxis that roamed the city's pavement were sent out each day from forty-five stables. Some would ply the streets looking for customers. Others lined up at designated stands near railway or ferry terminals. Others yet waited outside hotels, prominent churches, or city hall. Hotels often required a commission or kickback to use stands outside their entrance. Police put up stanchions and rope lines to limit the number of cabs that might wait at any stand in the center city.

Some years earlier, some of the drivers founded an association called Liberty Dawn. It was a mutual benefit group that paid sick and death benefits; the latter payment would guarantee the member a decent funeral. This association later joined the Teamsters International Union as Local 607. Before the union was formed a driver worked twenty-hour days and slept in a stable. After the union came about, his workday was fourteen hours and he could afford a small flat or accommodations in a rooming house. He generally earned $2 a day plus tips and drove a new carriage pulled by good horses.

1.13. A London Hansom 1895.

(Smithsonian Institution, Neg. 34, 417–E. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

A few words should also be offered on the patrons of these sometimes-not-so-genteel conveyances. Many passengers were rich or respectable, it is true. A fair percentage were businessmen hurrying to an appointment or a concerned parent needing to getting home quickly to a check on the children. But there was a strong belief that less savory members of our society were frequent users of these public carriers as well. Thieves, bootleggers, and gamblers seemed drawn to the taxicab. There was also the cheating husband who left his paramour in the privacy of a taxi rather than show his face on the streetcar. The bank thief might elude the police by hopping into a cab. Drunks too tipsy to navigate a short walk home would hail a cab. And then there was the prostitute, whose trade seemed to flourish even in the supposedly sanctimonious Victorian era. A Cincinnati newspaper of June 7, 1866, reported that a harlot “as gay and fashionable in dress and fair in face as she is deformed morally, flings herself into the hack and order[s] the nonchalant driver, who well knows her and all women of her class, to exhibit her on Fourth Street between Main and Elm, and then make for the Avenue.” The morality of American society showed no signs of improvement, but the size of the republic was definitely on the rise.

1.14. Portrait of Henry P. Brougham.

(Harper's Weekly, June 13, 1868)

As the new century dawned, New York and Brooklyn were consolidated, making New York City the second largest city in the world, with a population of 3.4 million. The U.S. census for 1900 reported a total of 36,794 taxi drivers in the nation. Most American cities had cab service, supplementing street railways, which remained the preferred mode of urban transport. But this status quo would radically change over the succeeding decades as strange new vehicles became more and more popular.

THE HORSELESS AGE

The motorized taxi carries us into the twentieth century, and because the focus of this book is the Victorian era, our discussion on this modern period of for-hire vehicles will be brief. Efforts to develop a practical horseless carriage had been under way since the eighteenth century. Nicolas Cugnot's steam wagon of 1770 was among the first of a long line of experimental vehicles that led to the present-day automobile. Battery-powered electric carriages were first tried for taxi service in London and New York in 1897 (fig. 1.16). They were silent and odorless, but they were also slow and heavy. The clumsy wet-cell batteries weighed 800 pounds and required frequent recharging. A fairly sizable electric fleet was installed in New York, but gasoline motor cars proved faster and more reliable and soon replaced the Edison dream for an all-electric world. By 1903 Manhattan had three thousand petrol taxis in service, running a combined 5,000 miles a day. Several years later, London's gasoline-powered taxi fleet was nearing sixty-four hundred vehicles. The horse-drawn Hansoms and Broughams were soon made obsolete.

1.15. A Brougham of 1890.

(The Hub, October 1890)

In Chicago, John D. Hertz (1879–1961) began to manufacture the famous Yellow Cab in 1905 (fig. 1.17). They would become familiar in most American cities. Harry N. Allen introduced a German invention, the taxi meter, in New York at about the same time. The Checker Cab Manufacturing Company began production in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1922. Its large, roomy sedan was designed specifically for taxi service. It became a favorite with the traveling public because it was so easy to get in and out of, compared to the typical American car. Drivers and operators liked them because of their durability. The last Checker was produced in 1983 and so ended, for many taxi patrons, the golden age of the American taxicab. Whatever the comfort level of modern motor cars might be, the taxi remains an active component in all major cities of the world today.

1.16. A New York electric taxi of 1897.

(Georges Dary, A travers l'électricité, 1903)

SUGGESTED READING

Armstrong, Anthony. Taxi! London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1930.

Belloc, Hilaire. The Highway and Its Vehicles. Ed. Geoffrey Holme. London: Studio Limited, 1926.

Berkebile, Donald H. American Carriages, Sleighs, Sulkies, and Carts: 168 Illustrations from Victorian Sources. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

___. Carriage Terminology: An Historical Dictionary. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978.

___. Horse Drawn Commercial Vehicles: 255 Illustrations of Nineteenth-Century Stage Coaches, Delivery Wagons, Fire Engines, etc. New York: Dover Publications, 1989.

Casson, Lionel. Travel in the Ancient World. London: Allen and Unwin, 1974.

Croal, Thomas A., ed. A Book about Traveling, Past and Present. London: William P. Nimmo, 1877.

Dollfus, Charles, et al. Histoire de la Locomotion Terrestre. 2 vols. Paris: Sociéte nationale des enterprises de presse: Editions Saint Georges, 1935.

Geogano, G. N. A History of the London Taxicab. New York: Drake Publications, 1973.

Gilbert, Gorman, and Robert E. Samuels. The Taxicab: An Urban Transportation Survivor. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

1.17. Advertisement for a Yellow Cab, model “O,” 1921.

(Lad G. Ahren collection)

Green, Susan, ed. Horse Drawn Sleighs. 2nd ed. Mendham, N.J.: Astragal Press, 2003.

Hazard, Robert. Hacking New York. New York: C. Scribner's Son, 1930.

King, Edmund F. Ten Thousand Wonderful Things. 1859. London: G. Routledge and Sons, 1860.

Kirkman, Marshall M. Classical Portfolio of Primitive Carriers. Chicago: World Railway Publishing, 1895.

Kouwenhoven, John A. The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York. Garden City, N.J.: Doubleday, 1953.

Lay, Maxwell G. Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles That Used Them. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Maresca, James. My Flag Is Down: Diary of a New York Taxi Driver. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1948.

Mooney, William W. Travel among the Ancient Romans. Boston: R. D. Badger, 1920.

Moore, H. C. Omnibuses and Cabs: Their Origin and History. London: Chapman and Hall, 1902.

Papayanis, Nicholas. Horse Drawn Cabs and Omnibuses in Paris: The Idea of Circulation and the Business of Public Transit. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Scrimger, D. L. Taxicab Scrapbook: A Pictorial Review of the Taxi. Charles City, Ia.: Scrimger, 1979.

Stratton, Ezra M. The World on Wheels. New York: B. Blom, 1878.

Vidich, Charles. The New York Cab Driver and His Fare. Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman, 1976.

Wakefield, Ernest H. History of the Electric Automobile. Warrendale, Penn.: Society of Automotive Engineers, 1994.