N 7

7

River Steamers

White Swans on the Inland Rivers

EUROPEAN SETTLEMENTS WERE WELL ESTABLISHED ALONG THE Atlantic Coast by the beginning of the eighteenth century. The Allegheny Mountains discouraged migration to the west, except for traders, military men, explorers, and the eccentric. A few forts and trading posts were established by the French, which led to territorial disputes with Britain. A war erupted in 1756 between these European powers. Britain won the conflict and established its claim to most of North America. The British Colonial Office prohibited settlement in these territories as a way to end conflicts with the Native Americans who inhabited these vast lands. The peace was kept only temporarily; however, American independence reopened the settlement issue, and by the late 1780s land-hungry settlers began moving into the Ohio country. The only easy route to get there was the Ohio River, so the pioneers gathered at Pittsburgh and were carried down the river in flatboats piled high with people and their sundry possessions. The Ohio River was the east-west branch of two other major inland rivers: the Mississippi and the Missouri. There were also about fifty tributaries large enough to allow navigation by smaller boats, in some cases for several hundred miles. Nature also provided an excellent regional waterway – the Great Lakes. By 1850 the center of the nation was filling up with people. There were a dozen new states and about ten million residents. Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis were expanding. Most of this growth can be attributed to the rivers.

7.1. The bow-on view of the Memphis 1860 shows the size, grace, and elegance of the American packet boat. This vessel was designed for the cotton trade on the lower Mississippi River. Its main deck was an impressive 71 feet wide.

(E. J. Reed, ed., Transactions of the Royal Institution of the Naval Architects, 1861)

The rivers became the principal avenue of commerce for the western settlers. They adopted a variety of water crafts, including canoes, dugouts, flatboats, and keelboats. The latter were the most finished style of vessel on the river system; they had a cabin, a prow, and a stern and were intended for long-term service. Regular monthly keelboat service between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati began in January 1794. The 20-ton vessel was well armed with muskets and an ample supply of ammunition. Separate cabins for men and women were provided, as was food and liquor at reasonable prices, and onboard toilets eliminated the need to stop en route. Each year about five thousand keelboats were powered by men using oars or poles; the river current carried the vessels downstream. Keelboats and flatboats drifted down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers as far south as New Orleans. The trip normally required two months; poles, oars, and sails assisted in passage, but progress was extremely slow. The return trip was far slower and more difficult – so much so that flatboats were routinely broken up for their lumber, and crews walked home. A favored route was the Natchez Trace, a narrow path carved out by animals centuries before any humans lived in the area. It ended at Nashville, where travelers would follow other woodland trails homeward. Today the Natchez Trace is a paved parkway.

It should not be assumed that the inland rivers allowed navigation year round. Even the largest of these streams were problematic. The Mississippi River is interrupted by falls at St. Paul, Minnesota, and is encumbered by many twists and turns, some at right angles. The channel can shift in a few days and move a mile away. In 1876 the channel shifted 11/2miles below Vicksburg, isolating this important port from regular river services. Boats could land at Vicksburg only during times of high water. At the same time, the Mississippi is generally 3,000 feet wide most of the way from St. Paul to New Orleans. Its bends widen out to a mile or a mile and a half, allowing plenty of space for steering. The Mississippi generally has enough water volume to offer enough draft for navigation. This is especially true of the lower Mississippi, where the depth of the stream is considerable. The river divides into several branches below New Orleans to exit into the Gulf of Mexico. None of these branches were deep enough for easy navigation by seagoing ships, however, and in the 1870s jetties were built to scour out the South Pass Channel. The father of waters was like all American rivers; it had its share of snags, sandbars, and floods that hamper river traffic. It was subject to freezing at the northern end but rarely had this problem below Cairo, Illinois.

The Ohio and Missouri Rivers were more troublesome than the Mississippi. Their defects were more serious and were only partially corrected at considerable expense. The Ohio River begins at Pittsburgh and drifts in a southwesterly direction, 981 miles, to Cairo, where it joins the Mississippi. It suffers from low water and freezing that can shut down navigation for weeks or even months at a time. Typically summer and fall are the dry seasons. Around Thanksgiving the rains return and the river rises; floods commonly develop in January. Freezing is of shorter duration and rarely lasts more than a few weeks, but when the thaw comes the ice piles up in dams and advances southward, crushing everything in its path. Many riverboats met their end that way. It is also true that freezing was less common than low water, and a decade might pass without the river freezing solid. Boat operations relied on special low-water boats. The larger boats were tied up temporarily. The 1880s were bad years for low water. In August 1883 the Ohio River dropped to just 23 inches at Cincinnati. Nothing much larger than a rowboat could move. The drought returned the next May, and the boats that normally made ten trips to New Orleans during the year did well to make one to three trips. In times of especially low water, tiny steamers known as bat wings were put to work moving whatever freight and cargo their narrow decks could handle. The solution to the Ohio River's low-water problem was solved by a series of locks and dams financed by the federal government, which were completed between 1875 and 1929.

The Ohio River had a major obstacle near its center; the Falls of the Ohio, between Clarksville, Indiana, and Louisville, Kentucky, is actually more of a falling rapids. It drops just 22 feet in 2 miles. When the river was high, boats could run the falls in both directions, but this was true only periodically, so passengers and cargo were portaged around the rapids, thus adding to the slowness and expense of the trip. After much discussion, a canal was opened late in 1830 around the falls, but it was built on too small a scale and was enlarged in 1872. Large boats continued to shoot the falls for many years under the guidance of skillful pilots. Most such runs were successful, but enough boats were lost that a lifesaving station was established to oversee the dangerous operation.

Another danger already alluded to was the presence of snags and sawyers in the river. These were large submerged logs that came from trees growing along the shore. Trees need water and grow rapidly where it is plentiful. What better place to find it than on a riverbank? Very often the bank is weakened by the stream and at some point a tree topples into the river. The branches break off or fall away in time, but the trunk remains intact. It becomes waterlogged and sinks below the surface; this is the snag at its most dangerous, because it is so difficult to see. These very heavy logs could easily knock a hole in a wooden hull, especially if the boat was moving rapidly. Sinking occurred in a matter of minutes. The severity of the accident depended on the depth of the water and the timing of the collision. If it happened in a deep section of the river late at night while the passengers were asleep, the death toll could be significant.

Snags were the chief cause of steamboat accidents and accounted for 57 percent (about fourteen) sinkings a year. Fatalities were not inevitable, however, because some boats made it to shore before sinking or sank in water so shallow that the upper decks remained dry. Snag removal remained a leading concern of boat operators, and, once again, as much as they despised government interference in their private affairs, they seemed convinced that eradication of snags was a federal problem. The government did respond early, since the river system was seen as a national highway and necessary to the postal service. An effective snag removal program began in 1829 that greatly reduced this menace to navigation; however, political support for this program was inconsistent. The Whigs argued for funding; the Democrats remained opposed. By the end of the Civil War snag removal became a fixed line in the federal budget.

The Missouri River is a long, slender stream that joins the Mississippi River above St. Louis at St. Charles, Missouri, and crosses half a dozen states before ending in northwestern Montana. This 2,300-mile-long stream has been described as turbid and impetuous and frequently alters its channel. It was clearly not ideal for navigation, but because the river reached so far west, it was a logical route for travelers. Lewis and Clark followed it on their epic trip of exploration, and it served hunters and others seeking a way west equally well. Riverboats became plentiful on the eastern end of the Missouri as far as Council Bluffs, some 660 miles from the Mississippi. The upper reaches of the Missouri River required very light shallow-draft vessels. They were Spartan in nature and ran successfully on only 30 inches of water. Boats of this type ran as far as Fort Benton, Montana, and were largely used to service the fur trade. As with the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, the Army Corps of Engineers has improved portions of the “Big Muddy” for navigation.

EVOLUTION OF THE INLAND RIVERBOAT

The early years of river navigation were largely a downstream business. There was no easy way to propel boats upstream against the current. Human power was sufficient only to power empty or lightly loaded vessels. Many inventors in the western nation designed steamboats to answer the need for a vessel powerful enough to overcome river currents. The British and French were active in such efforts, but Americans seemed especially attracted to steamboat experiments. Some of those tested were technically successful. For example, after many experiments John Fitch operated a steamboat on the Delaware River in the summer of 1790. The boat offered service between Philadelphia, and its suburbs Trenton and Burlington, New Jersey. It ran on a regular schedule at speed from 6 to 8 mph. The public was not ready for such an advanced mode of travel – steam engines were unfamiliar and viewed as dangerous. Another American, more artist than engineer, Robert Fulton reintroduced a steamboat on the Hudson River in 1807. He housed passengers inside an elegant cabin; the engine and boiler were out of sight. Fulton was smooth and gentlemanly – so unlike Fitch – and he was able to convince the traveling public that his low-pressure steam plant was as safe as a nursery. Fulton's principal backer, Robert Livingston, was the head of an elite New York family and a prominent diplomat. His endorsement was important in creating a positive reception for this new way of traveling.

The partners built more boats for service on the Hudson River, New York Harbor, and Long Island Sound and planned a monopoly to control steamboats on every American waterway. Livingston had enough political connections to receive such a grant from the state of New York and several parishes in Louisiana. However, although they were less successful elsewhere, in 1824 the U.S. Supreme Court declared that our national waterways were open to all citizens. Fulton and Livingston had died a decade earlier. In 1810 Fulton pushed ahead with plans for an inland riverboat. He established a yard in Pittsburgh and hired Nicholas Roosevelt to manage the project. The engine was built at Fulton's shop in Jersey City and was carried overland by wagons to Pittsburgh. The boat was similar to those Fulton had built for Hudson River service. It was narrow, long, and deep – a suitable shape for rivers like the Hudson, but very wrong for the shallow Ohio River. The boat, named the New Orleans, was finished but could not proceed because of insufficient draft. By late October 1811 the river rose and the New Orleans left on its epic voyage. No passengers could be convinced to join Roosevelt and his crew, as the strange and futuristic craft was viewed with suspicion. All went well, however, until the New Orleans reached Louisville. The water was not deep enough there to shoot the Falls of the Ohio, so the boat returned upstream to visit Cincinnati. Suspicion and indifference were instantly overcome – the little sawmill on a raft had proven herself. She had bucked the current and moved upstream without difficulty. The steamboat was a reality, one that would revolutionize river travel. The New Orleans continued its trip southward and reached New Orleans in December 1811. She was found to work well in the deep water of the lower Mississippi River and continued operations there until sinking in 1814. Fulton died a few months later, ending his dreams of fame and fortune from a steamboat empire.

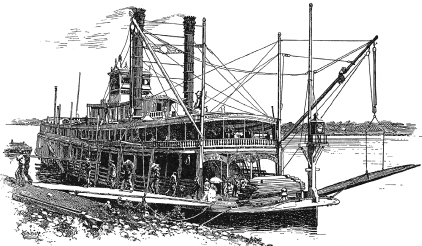

Many others were ready to build and improve steamboats for the western rivers. A few, such as Henry Shreve, can be named, but most of the pioneers are largely anonymous or forgotten. What they did, however, is well recorded. Fulton's steamboat was radically altered between 1815 and 1830. The hull was made flat and wide rather than narrow and deep. This single change made it suitable for shallow-river travel. The boat would skim over the top of the water rather than plow through it, and the hull became a buoyancy chamber. The hulls were built from heavy oak or locust timber. The bottom planks were often 3 inches thick. The hull was heavy and strong to resist snags and rocks. To gain more room for cargo, the first deck was made to overhang the hull. The overhang was considerable so that a hull 20 feet wide would support a deck that was 35 feet wide. The section that overhung the hull was called the guards. The guards also served to protect the paddle wheels from colliding with passing boats or other obstructions. They added to the peculiar appearance of the American riverboat. It was also a feature that remained in favor until the end of the steamboat era. This feature is illustrated in figure 7.1.

The engines and boilers were placed on the first deck. Freight was placed on the same deck in any open space available. Emigrants and other deck passengers were housed on the main desk as well. First-class passengers were housed on the second, or boiler, deck in small cabins that surrounded a large central cabin. This chamber served as both a sitting and dining room. A smaller and much narrower cabin rested on top of the second-deck cabin. It was called the texas and was divided into small compartments for the crew. The pilothouse was placed on top of the texas. The steering wheel was inside the pilothouse. The upper works – that is, all of the cabin decks above the hull – were very lightly constructed in an effort to reduce the boat's weight so that more cargo could be carried. This part of the boat was weak and flammable. If the boat caught on fire, the cabins would burn quickly. If the boat sank, the upper works sometimes broke loose from the full and floated away or sank. The oversized upper works and undersized hull made the American riverboat a most unusual looking and unique vessel. On the water it appeared to be all cabins and looked like a hotel gone adrift. The American riverboat was described as a most un-navigable-looking craft. It was a huge structure of flimsy wooden pieces, windows, doors, railings, long verandas, and great chimneys. These smoke pipes were topped with decorative crowns that resembled the paper frills that adorn broiled lamb chops. Humorists said the boats looked like a floating sawmills except for the glory of the white paint and the elegant artwork on the wheel boxes. This general plan, for all of its peculiarities, proved very successful and was never greatly altered during the history of the riverboat.

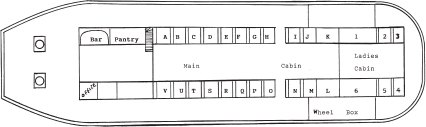

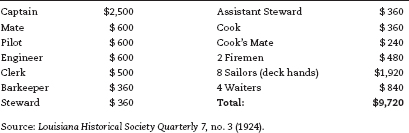

To illustrate the development of inland riverboats we will offer several examples of such vessels during the nineteenth century. The New Orleans II is a well-documented vessel of 1815 described by German visitor J. G. Flugel during a visit to New Orleans in 1817. The vessel was built in Pittsburgh at Robert Fulton's yard, where the original New Orleans had been built in 1811. The 1815 New Orleans was 116 feet long and 20 feet wide. She carried no sails and was capable of running 3 to 4 miles an hour upstream and 9 to 10 mph downstream. The 30-foot-long ladies’ cabin was at the stern below the top deck. It was elegantly furnished with white window curtains, sofas, chairs, looking glasses, and an ornamental carpet. There were twenty built-in beds enclosed with red curtains and mosquito netting. The men's cabin was on the top deck. It measured 28 by 42 feet and was described as a “round-house,” which presumably means the ends were rounded. This space was divided into thirteen staterooms, each having two berths. Each berth had a window. The mattresses were stuffed with Spanish moss, easily found in the Louisiana woods. The bed linens were handsomely flowered. The furniture included settees, chairs, tables, and a large gilt-frame looking glass. Forward of the men's cabins was a bar room, managed by a most agreeable attendant. The captain's room was on the starboard side. Separate cabins were also provided for the chief engineer, the bar keeper, and the clerk. The kitchen was forward of the engine. A bedroom for the mate and pilot was located ahead of the kitchen. The deckhands and firemen had spaces in the forecastle for twelve berths, a table, and seats.

Flugel's description seems to mirror Fulton's general design for Hudson River boats. The New Orleans II consumed six cords of wood a day, which cost $2.50 per cord. Passengers could enjoy a view of the river from a roof deck on top of the men's cabin. It was surrounded by an iron railing. An awning protected passengers from the sun. The boat was fitted with a 4-pound swivel gun that was fired to signal arrivals and departures. The crew consisted of twenty-four people: a captain, mate, pilot, engineer, clerk, bar keeper, steward, assistant steward, cook, cook's mate, two firemen, eight deckhands, and four waiters. The total yearly salary paid to the crew was $9,720. The boat's route was limited to New Orleans and major towns as far as Natchez, some 314 miles upriver. The fare between New Orleans and Natchez was $30 upstream and $15 downstream. The captain claimed that net proceeds per trip were never less than $4,000.

Well to the north of Louisiana, a description was published in a Cincinnati newspaper of the General Pike, named in honor of pioneer military officer and explorer Zebulon Pike. The hull for the center-wheel steamer was launched in September 1818. It was outfitted as a deluxe passenger carrier. Its keel was 100 feet long and the beam measured 25 feet. According to an engraving published in 1873 she was no thing of beauty externally. Yet her interior was elegant and comfortable. The main cabin was 40 feet long and 25 feet wide. Marble columns, rich carpets, and mirrors gave the space “an air of elegance which borders on magnificence.” There were twenty-four built-in berths in this space, each enclosed by crimson curtains. In addition six staterooms were at one end of the main cabin and another eight at the other end. Special settees designed for sleeping offered space for another sixty overnight guests. The General Pike ran upriver between Louisville and Cincinnati in thirty hours at an average of about 6 mph. By 1823 she was worn out and retired.

The Tecumseh of 1826 was in most respects a near duplicate of the New Orleans II. She operated on both the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and is remembered for her speed. The hull was built by the Stephen Weeks yard located in the east end of Cincinnati. Weeks and his several sons were New York boat builders who relocated to Ohio around 1820. Their products reflected the style of boat they had built for service in New York waters. The passenger cabin was at the stern of the main deck. The ladies’ compartment was below the main cabin in the hull. The vessel had a figurehead, a bowsprit, and a decorative panel on the stern transom. The keel measured 130 feet; the hull was 22 feet wide by 7 feet deep. A watertight compartment in the bow was designed to contain snags and prevent the boat from being sunk by predatory logs. Work started in the summer of 1825, and the hull was launched in February of the next year. She was fitted with a single-cylinder engine that featured a flywheel and clutches so that one paddle wheel might be disconnected to aid the boat in making quick turns. She drew 62 inches of water without cargo and consumed between 24 and 30 cords of wood a day.

The arrangements of the cabins and passenger spaces followed the eastern plan used for steamers in the Hudson River and Sound established by 1810. It was essentially the traditional plan used by sailing ships. The cabin was at the stern, the bunks were built in, and there were no staterooms. The top cabin was an open veranda covered only by canvas with a railing around the edges. The exterior of the boat was very plain, the only adornments being the figurehead and transom. When her first trip began on March 10, 1826, the river was high and the weather was wet and foggy. Somehow the pilot lost his way, and the Tecumseh veered out of the channel and over the bank, where she became wedged between two trees. The damage was minor, and once free from the trees she began service between Louisville and New Orleans. She could not compete with the larger boats in this service, however, and so took up cotton shipping on the Tennessee River. In 1827 the Tecumseh demonstrated her speed by running from New Orleans to Louisville in just nine days and five hours. The notoriety was sweet, but the boat was not a moneymaker. In 1829 she was retired. Her machinery was removed for a new boat in 1830, and the hull was burned in June 1831 to recover the spikes and other iron fittings. Five years was the average life for a riverboat at this time, so the Tecumseh's demise was right on schedule.

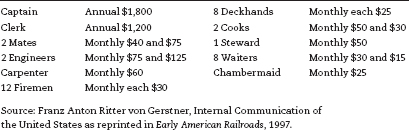

Foreign travelers offered some of the best information available on early American life. Austrian engineer Franz von Gerstner explained Ohio River steamers of 1839 in considerable detail in just a few pages. Rather than generalize, he used specific examples. By the time of his visits, the distinctive flat-bottom boat with two decks had replaced the eastern, or Fulton-style, vessel previously described. Boats were built in sizes ranging between 100 and 600 tons. Smaller vessels had single-cylinder engines with flywheels 10 to 15 feet in diameter. Larger boats had two-cylinder engines, one for each paddle wheel. Steam pressure was normally 70 to 120 psi and in a few cases 150 psi. Some boats recouped their purchase price in one year of operation. They were lightly built and rarely remained in service more than five years. Depreciation was generally figured at 25 percent per year.

7.2. The boiler or second deck of the Homer of 1832 shows the general plan long in favor for river steamers. Small sleeping rooms called staterooms surrounded a large, open cabin used as a combination dining room and parlor space.

(After a drawing made by Karl Bodmer in January 1833; Karl Bodmer's America, 1984)

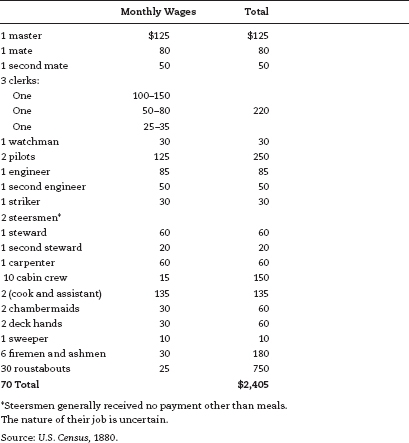

Gerstner offered the following particulars on Diana, a packet built in Louisville in 1838 for service to New Orleans. The Diana was a first-class boat built at a cost of $40,000. She was 170 feet long; 23 feet wide; and 7 feet, 2 inches deep. She drew 4½ feet empty and 6½ when loaded. Her normal time to New Orleans was four and a half days downstream and six and a half days upstream. She had seventy sleeping berths and charged passengers $40 downstream and $50 upstream. Deck passengers paid only $8 but received no meals or sleeping berths. They could travel for $5 if they assisted in taking on wood for fuel. The Diana's gross receipts for the 2,900-mile round trip between New Orleans and Louisville were on average $5,100 for first-class passengers; $650 for deck passengers; $1,937.50 for freight; and $240 for mail, for a total of $7,927.50. Expenditures for the round trip were $4,000; $1050 of this amount was for fuel. Monthly wages for thirty-eight crew members equaled $1,785. The boat made twelve round trips a year. The year's net income for Diana, including depreciation, came to $37,130, or very nearly the original cost of the vessel. The deck plan in figure 7.2 is for the Homer, a vessel very similar in size and date to the Diana. The Homer was built in 1832 in New Albany, Indiana, across the river from Louisville. The exterior of a generic boat of this period is reproduced in figure 7.3. This engraving shows a typical western riverboat of the late 1830s. The engraving is likely a reasonably accurate depiction of the Diana described by Gerstner during his 1839 inspection of such vessels. Boats of the period were plain and utilitarian in appearance. They were almost entirely devoid of exterior ornamentation. There were no jigsaw scrolls, no gingerbread, nor even fancy smokestack tops. The excesses of steamboat gothic became fashionable after 1860 and continued into the 1880s and 1890s.

By 1850 larger boats were running between major cities such as Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Considerable details on the Buckeye State were recorded in the 1851 edition of Thomas Tredgold's book on steam navigation published in London. This roomy yet plain steamer was 260 feet long and 54 feet wide. The hull was 29 feet; 4 inches wide; and 6 feet, 6 inches deep. This sizable vessel drew only 4 feet of water loaded and ready for service. The main passenger cabin was as long as many steamers running in the 1830s; it was 192 feet long and 15 feet wide. A separate ladies’ cabin, to the rear on the second deck, added another 40 feet to the main cabin. There were small cabins at the front end of the main cabin for the bar and excess baggage. Fifty-four sleeping cabins surrounded the main or central cabin. Each of these 6-foot-square compartments, or staterooms, contained a bunk bed and little else. The ladies’ washroom and toilet were on the starboard side of the second deck behind the paddle wheel house. The men's room was on the opposite side of the vessel. In April 1850, just a few months after entering service, the Buckeye State made an upriver trip to Pittsburgh from Cincinnati in fifty-four hours. This included sixty-two landings to pick up or drop off passengers and cargo. One hour of the 465-mile journey was lost due to fog. Fifty-four hours was considered good time on the river in 1850. The downriver trip normally took thirty hours. The Buckeye State was part of the Pittsburgh and Cincinnati line, which offered daily service between these river locations for a one-way fare of $6.

7.3. This Ohio River steamer was sketched by the Scottish engineer David Stevenson in 1838 to represent a typical boat of that time.

(David Stevenson, Sketch of the Civil Engineering in North America, 1838)

Size and decorative excess were combined in the Great Republic completed at Pittsburgh in 1867. This large, handsome vessel measured 335 feet in length yet drew only 4½ feet of water when loaded. She had fifty-four staterooms, each 8 feet square, and a palatial main cabin that measured 267 feet by 28 feet. The interior was steamboat gothic in all of its excesses and magnificence. Every surface was ornamented in white and gold. The carpet was English velvet rich in roses and scrolls. Adorning the walls were sixty-six oil paintings depicting river scenes around the nation. The silverware and table china were made especially for the boat. The Great Republic's stained glass was rivaled by that of other boats, such as the J. M. White of 1878. They were chaste in execution but had a bust of statuary in the center of each light. The glass was a pearl gray or a blue background enclosed by a wreath of ivy. The borders were made in purple and gold shades. The Natchez of 1879, the seventh boat of that name, had twenty-two stained-glass clerestory windows, each with an etched portrait of a Natchez Indian. They were rendered in soft tones of tan, russet, and brown. The sunlight coming through these stained-glass windows created a kaleidoscope of color. Artificial light reflected off them at night as it did off the mirrors and cut-glass prisms attached to the chandeliers. A few boats had interior statues; the Eclipse of 1852 had a gilt statue of Andrew Jackson in the main cabin and one of Henry Clay in the ladies’ cabin. Many boats had large silver-plated water coolers at one end of the main cabin (fig. 7.4). These containers sat on a tall wooden pedestal and were almost 6 feet tall. Silver cups attached by a light chain were available to all who cared to drink. Silver cake stands, cream-and-sugar sets, and cut-glass bowls added to the glitter of the dining room. A fifteen-room nursery was located below the ladies’ cabin. It included its own washroom and ironing facility. The boat cost an estimated $350,000.

7.4. A silver-plated water cooler stood at one end of the main cabin on board the Anchor line's City of Providence. Silver cups were attached to the cooler by small chains and were used by anyone desiring a drink.

(Harper's Monthly, January 1893)

The Great Republic left Pittsburgh on her maiden voyage on March 14, 1867, making stops downriver so that visitors might have a firsthand look at this incredible example of marine architecture. The boat was bound for service on the Mississippi River, so everyone along the Ohio River knew they would have only one chance to see the river giant. During her brief stop in Cincinnati 25,000–30,000 people came to visit the Great Republic. Louisville was next, and because the boat was too wide for the canal, she was run over the falls. She did this in a fine style, in part because of high water and in part because of expert piloting. By March 29 she was at Memphis and her working career on the lower Mississippi had begun. Being big and beautiful did not guarantee success. In less than two years the Queen of the River had rendered her owners bankrupt. New investors put her back in service but with no better result. In 1876 the Great Republic was rebuilt and renamed the Grand Republic. In May of that year she carried Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil from St. Louis to New Orleans. More trips followed, often with huge cargoes, yet a steady profit seemed to elude the Grand Republic. During a dormant interlude when she was laid up at St. Louis for a time, she caught on fire early in September 1877 and was reduced to ashes.

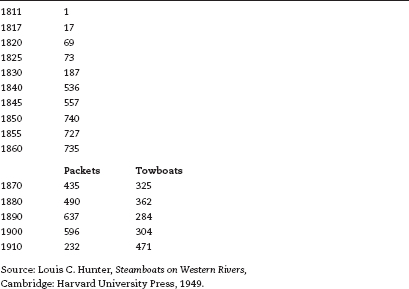

Readers should not assume that the Great Republic failed because the riverboat industry was in trouble. The popular belief that railroads stole traffic away from the rivers soon after the Civil War is somewhat erroneous. They did begin to take over long-distance passenger travel to a large degree as well as time-urgent cargo shipments. However, river traffic remained strong until the 1880s. At the same time, new passenger boats were being built. Some were of a good size and quality, such as those made for the Anchor line that offered service between St. Louis and New Orleans. One of the largest and most elegant vessels to serve on the inland rivers, the J. M. White, entered service in 1878. It was just slightly smaller than the Great Republic but was no less grand or costly. It was noted for its fine stained-glass windows and excellent food. It also featured large staterooms, some measured 9 by 14 feet. The boat made money because it was managed by an experienced river man. The White grossed $15,000 a trip and paid for itself over and over during its brief service life.

River steamers of the post-Civil War era were proving more reliable than their prewar ancestors. This is true in part because of more consistent snag removal, federal inspection of boilers and hulls, as well as the testing of key employees like pilots and engineers. In October 1879 the Louis A. Sherley had completed 26,920 miles and 946 trips between Cincinnati and Louisville in three years and two months. The Fleetwood of 1880 was another steady performer. During 1888 she ran every day and never missed a trip. Water levels that year were good on the Ohio River, allowing this big boat to perform steadily. At the same time, some boats continued to be very profitable. A Missouri River boat, the Waverly, paid for herself ($50,000) on its first round trip to Fort Benton in 1866. In June of the following year she returned to St. Louis loaded with bales of buffalo, wolf, deer, and antelope skins. In 1896 the Virginia, an Ohio River stern wheeler, earned enough to repay her owners their investment in one season.

Our final example of a Victorian-era river steamer, the Queen City, was completed in June 1897 for Ohio River service between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. This was a well-made boat but not a deluxe or extravagantly finished vessel. She was of a more modest size than giants such as the J. M. White or the Great Republic. The hull was 235 feet by 44 feet and was a wooden structure in keeping with western riverboat tradition. The main justification for choosing wood over steel was that the cost was greatly reduced. The general arrangement was equally old-fashioned; the arrangement of cabins and machinery was unchanged from boats built sixty years earlier. Mounted on the front deck was a landing stage that could be lowered to the riverbank to load passengers and cargo. This feature dates back to almost the beginning of the western steamboat, because landings were made anywhere along the riverbank, not just in towns where wharf boats were available. A farmer might want to send some sheep upriver to market. He would wave a white flag in the daytime to an approaching boat and hope it would pull over. If the boat ignored his signal, he would try the next boat. At night he would build a fire on the bank. The same signaling method was employed to fetch a steamer to take family members up or down the river. Most passengers were seeking transport to a nearby river town. Going by boat was often about as fast as going by train, because trains often had to take a more indirect route. However, for long-distance travel the train would be faster, and the routing, unless unusually complicated, was of less importance.

There were features about the Queen City that set her apart from her ancestors. Electric lighting was a relatively new invention. Power steering was another fairly new system on riverboats. Folding chimneys were introduced soon after the Wheeling Bridge opened in 1849, but they became more of a necessary as an increasing number of bridges crossed the Ohio River. In times of high water, boats lowered their smokestacks to pass under the bridges. That the Queen City was a stern wheeler set her apart from earlier packets, which were largely side-wheelers. The fact that the wheel shaft was nickel steel was surely an improvement over the wrought-iron shafts formerly used.

At the time the Queen City entered service on the Ohio River, boat operators could still boast of an investment of $8.5 million in their various vessels. They were carrying 7 million tons of freight and 1.5 million passengers a year. As to the boat itself, she proved durable, especially for a wooden-hulled vessel, and remained in service until 1933. Her hull was used as a wharf boat in Pittsburgh for another seven years.

RIVER TRAVEL: COMFORTS AND DISCOMFORTS

Riverboats were considered one of the nicer ways to get around in the Victorian era. They were roomy with interior space to move around inside. Those seeking fresh air could stride around the verandas or climb up to the hurricane deck or the pilothouse. On fair days a chair or bench on the veranda offered seating with an enjoyable river view. The tree-lined banks, the towns, farms, and passing steamers were all of interest. Flat boats were still plentiful until around 1880. The food was generally good and plentiful. It was served on time and at regular intervals. Toilets, wash basins, and clean towels were available at all times on the better boats. The bathrooms were large facilities intended for the first-class passengers, much like those found in any public facility such as an airport or school. Separate rooms were provided for men and women. Stoves kept the main cabin, which was illuminated in the evening, tolerably warm during the winter. Pioneers would remember their first river trip on a flatboat with only a tent for shelter. They could hardly believe the luxury and comforts commonly provided on the most average steamer. Some even had gaslights and hot-water baths. Other travelers would compare the riverboat to the stagecoach or walking through the forest mile after mile. Nothing available at the time could compare except the railroad; long-distance travel west of the Alleghenies by rail was not possible much before about 1855. Modern travelers, however, would find riverboats of the nineteenth century intolerable. The tiny sleeping cabins had no running water, heat, or toilets. The mattress and bedding would be unacceptable. Where were the TV, the Internet, the electric lights, and the air conditioning? The only way to educate contemporary travelers about the merits of river travel would be to have them spend several hundred miles traveling by stagecoach. Citizens of the twenty-first century have no conception of how soft modern travel is in comparison to what it was in the past.

7.5. A view of the interior of the ladies’ compartment of the steamer Planter in 1860 shows that even smaller packets had well-appointed spaces for cabin-class passengers.

(Author's collection)

Firsthand accounts are a rich source for what it was like to travel in early America. Some appear in books like Charles Dickens's published record of his visit to the United States in 1842. Others were published as articles in magazines of the time, while still others were handwritten and printed many years later by historical societies. Yale University Press published the journals of well-known architect Benjamin H. Latrobe (1764–1820) in 1977. In one of these volumes, Latrobe describes moving his family to New Orleans in the winter of 1820. Latrobe's family began the trip by road. They reached Washington, Pennsylvania, going by wagon and sleigh, in late January. The weather was so frigid, they stayed at an inn awaiting a thaw. They crossed on the National Road to Wheeling and boarded the Columbus, which was bound for New Orleans. The nearly new vessel was one of the largest in service. The trip should have taken only about eight days, but the Columbus was subject to breakdown. They laid over at Marietta, Ohio, for three days to replace a broken paddle-wheel shaft. The boiler required attention at Maysville, Kentucky. One of the paddle-wheel shafts cracked, resulting in another stopover. More stops were needed to fix other minor mechanical problems. The Columbus finally reached the Mississippi River late in March. The boat settled down and better progress was made. They finally reached New Orleans on April 3 or 4 (the record is unclear) after a trip that had required almost five weeks.

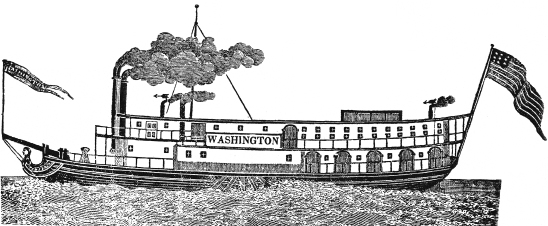

7.6. The Washington was completed in 1825. The figurehead and bowsprit were old features, but the passenger cabin on the second deck was an advanced feature. The boat lacked a pilothouse. It was 130 feet long.

(Frederick Way collection)

In April 1827 William Bullock, a British traveler, rode the George Washington from New Orleans to Louisville (fig. 7.6). In contrast to many of his countrymen, Bullock found the boat and the journey excellent. The accommodations were perfect and the cabins were furnished in the most superb manner. The veranda extended all around the boat on the upper level and was sheltered from the rain and sun. It offered a fine view of the surrounding scenery. The food was excellent as well and was served in a superior style. The ladies had a separate cabin with female attendants and a laundress. There was a library and smoking and drinking rooms for the men. The boat stopped twice a day for wood; fresh milk and other necessities were procured at this time, and passengers could go ashore for a brief visit. The trip upriver took only eleven days (1,500 miles) and cost about $40. Bullock was amazed as the boat passed impossible wilderness and unsettled lands without the least hazard or discomfort. The scenery on the lower Mississippi was flat, but it was lined with pretty homes, plantations, gardens, and sugarhouses. Sugar cane, rice, and orange groves made the land rich and productive. Unlike so many of his countrymen, Bullock found his American passengers to be pleasant, intelligent, attentive, and obliging. They were proud of their country and its democratic government and believed others should come and see what they had accomplished.

Bullock offered no details on the George Washington, but Captain Fred Way prepared such an account in more recent years based on original records. The boat was 130 feet long; 30 feet, 6 inches wide; and 8 feet, 6 inches deep. She entered service in 1825 and cost $31,982. The ladies’ cabin was at the rear of the second deck. The decorations included a large mirror and oil paintings of Daniel Boone and Washington's farewell to his troops. Staterooms and beds were provided for sixty passengers. Forward of the main cabin was an open cabin with 101 hammocks for deck passengers. Normally deck passengers slept wherever space could be found on the first or main deck. No bedding of any kind was provided.

Basil Hall, a former British naval officer, traveled extensively in the United States in 1827–1828 with his wife and young daughter in tow. In general he recorded a favorable opinion on American riverboats, finding them comfortable and inexpensive. When he was ready to return to England by the summer of 1828, part of the journey was by river steamer from Cincinnati to Pittsburgh. It happened to be a hot and humid part of the summer. Everyone on the boat was suffering but no one more so than Hall's daughter. The Halls were concerned that she had contracted malaria. She became so ill that her parents began to despair that she might not survive their journey. Upon reaching Pittsburgh they quickly boarded a stagecoach for the East Coast. As the coach pulled uphill into the clear, cool air of the Alleghenies, their darling child began to show signs of recovering and her improvement continued. Hall's three-volume report on his American visit remains a testimonial to the positive features of American river travel. His excellent account became a standard reference in our young republic.

Other travelers in the 1820s present a less flattering verbal picture of river travel. In 1828 a Methodist minister named Peter Cartwright boarded the Velocipede at St. Louis bound for Pittsburgh. She was a small vessel and very crowded. The passengers were described as a “mixed multitude” and seemed largely composed of profane swearers, drunkards, gamblers, fiddlers, and dancers. Cartwright was a strong, charismatic man who worked to turn these fallen people away from their card playing to the merits of Christianity. Some boats of this time had no staterooms, but berths folded down from the sidewalls of the cabin for a bed. The ladies’ cabin was separated by a curtain. There were so few beds that a lottery was held each night to see who would win a bed and who would win a chair, bench, or table.

The dangers of river travel were recalled by a pilot on the Patriot, a first-class packet built in 1824. She was, however, built with secondhand machinery. By 1830 the elderly boilers were showing signs of distress. The boat was on its way to New Orleans and was nearing the end of the Ohio River. A passenger wanted off at the town of Trinity, Illinois. At the same time, the pilot was warned that water was very low in the boilers and that the engineer would pump them up to a proper level once the boat stopped at Trinity. But just before the landing was made, the forward end of the far-left boiler burst open like a cannon. The chimney on that side popped up into the air and crashed down on the pilothouse. The guy rods supporting the chimney became entangled with the steering wheel, and the pilot had to struggle through the wreckage to steer the boat to shore. The front deck was covered with debris and four wounded men. The forward deck was also on fire. The captain managed to quench the fire. Although three of the injured crew members died, none of the passengers were harmed. Normally after such a mishap the trip would be abandoned. However, Captain Levi James and his crew made temporary repairs and went on to New Orleans with one smokestack and five, rather than six, boilers. The Patriot continued running for another year.

Most river travelers made their journeys for conventional reasons of business or pleasure. Some, however, traveled for science and art. A few made trips that were bound to be dangerous and uncomfortable because steamboats went to inaccessible places, such as the upper reaches of the Missouri River. The American Fur Company began sending boats into these remote and unsettled areas in 1831. They carried trading goods, ammunition, and a grisly crowd of trappers, hunters, and other frontiersmen to this outpost beyond civilization. No ordinary citizen would think about booking passage on one of these boats. However, Prince Alexander Philipp Maximilian of the small Germanic state of Wied-Neuwied was eager to make the trip and did so in 1833. He was intent on documenting the American Indian tribes of the region before they are contaminated by civilization. A self-taught American artist, George Catlin, traveled by steamer up the Missouri River at the same time as the prince. He lived with the tribes, who came to trust him. He made hundreds of paintings showing all phases of Indian life. His portraits preserved a likeness of their leaders and their ordinary people. Prince Maximilian kept a careful journal of his trip but depended on a Swiss artist to prepare illustrations to document Indian life. Much of this material now resides in the Joslyn Art Museum of Omaha.

In 1843 John James Audubon would retrace the journey of Catlin and the prince to paint four-legged creatures of the forest rather than American Indians. He would travel on a new American Fur Company boat, the Omega. The ladies’ compartment was reserved for Audubon and his several associates. The artist had his own room and made this area complete with a double bed and a stove. The boat was well stocked with food, including six thousand eggs and plentiful boxes of wine and whiskey. They shared the boat with a large number of frontiersmen who were drunk or half drunk, with almost none in the crowd who could be registered as completely sober. They would sing and howl like madmen or fire their guns to break the silence of the Missouri River valley. The boat fought its way over sandbars much of the way upstream. Audubon would leave the boat to search for birds and quadrupeds. He brought dead specimens back to his cabin for examination and sketching. The Omega reached Fort Union, Missouri, just above the mouth of the Yellowstone River, on June 13, 1843, after fifty days of travel. The material gathered along the Missouri River resulted in the publication of three volumes with 150 folio plates. Art and science were thus assisted by the humble riverboat.

The average riverboat patron rarely encountered a vulgar crowd like those associated with Missouri River packets. He would expect, however, a mixture of people. American sailor and fur trader Joseph Ingraham observed what he called a strange medley of people on his boat heading upriver to Natchez in 1835. There were merchants and planters in the main cabin and a few sporting gentlemen who won handily at the card tables. The men played cards to pass the time and seemed ready to lose a goodly sum. There was an important-looking French gentleman who bore the title of general. The cotton planters wore broad-brimmed white fur hats but were otherwise clothed in a careless half sailor-like and half gentleman-like attire. In contrast was a Yankee lawyer in a plain black coat, closely buttoned, a narrow hat, and gloves. A minister sat alone by the stove reading a small book. In the place of black he wore a bottle-green coat, a fancy vest, and white pantaloons. There were two or three fat men in gray and blue, several Germans, a sharp-nosed New York speculator, and four elderly French Jews with noble foreheads. The most interesting woman was an intelligent young lady from Vermont. She possessed a cultivated mind and a full share of Yankee inquisitiveness. Ingraham's ruminations were suddenly interrupted by the loud report of the boat's cannon, which made the boat tremble through every beam. The boat was about to land at Natchez.

Dr. T. L. Nichols recalled a trip down the Ohio River in 1845 that was a delightful adventure. He described the river as charming and grandly beautiful. It was broad and splendid in great reaches, with graceful curves and picturesque banks. The crewmen sang merrily as they stoked the furnaces. The boat got stuck on a sandbar but floated off the next morning. The clear sunlight glittered on the river and lit up the forest in a golden radiance. Blue sky and cool air added to the scene. When the boat stopped for wood on the lower Mississippi, Nichols jumped to the shore. The air was soft and delicious. The gardens were filled with flowers, the rose bushes were blooming, the oranges had turned from green to gold, and the figs were ripening in the sun.

A few years earlier Charles Dickens toured America, traveling down the Ohio River to Cincinnati on the steamer Messenger, but he found it a cheerless journey. Meals were eaten in silence, and after dinner the men would stand around the stove, spitting without uttering a word. A few days later the English novelist was on a second boat going downstream. On his way west he happened upon a Choctaw chief who was cultivated and engaging, and the two struck up a lively conversation. Dickens was pleased that the chief had read several of his books. He invited his new friend to visit England. The chief responded that the Englishman should come to Arkansas for a buffalo hunt. Dickens later reflected that the only really engaging person he had met during his travels was an American Indian, which most U.S. citizens dismissed as savages.

Another English novelist, one even more prolific than Dickens, came to America in 1862. Anthony Trollope found steamboating when it was in a most distressing slump. Most of the boats at Pittsburgh were tied up, because the Confederates had stopped navigation at Vicksburg. Later in his tour Trollope found boats running on the upper Mississippi and cruised the river from La Crosse, Wisconsin, to Dubuque, Iowa. He was on the boat for four days but found his fellow passengers strangely silent. If he asked a question, they would answer him in a civil fashion, but there it ended. None seemed inclined to converse. The men on the boat would sit together for hours, hardly speaking a word. He found the women equally taciturn. They seemed hard, dry, and melancholy. He was also astounded by their general indifference to the splendid scenery around him, declaring that the Rhine River did not compare to the bluffs of the upper Mississippi. Added to the bluffs were the woodlands, Lake Pepin, and the color of the scenery. Trollope went away wondering about the unresponsiveness of Americans to the joy of life and the beauty of nature.

Walt Whitman was another literary figure who traveled by riverboat and made a record of his journey. In February 1848 he was on his way to New Orleans to become editor of a newspaper. This was a new experience, for he had never been west of the Hudson River and was about to visit unfamiliar regions of America's interior. He boarded the packet St. Cloud at Wheeling, West Virginia, for a twelve-day sojourn down the inland rivers. The scenery was dismal during the winter, and, except for a few large towns, most stops were made at villages or dismal wood yards populated by loafers and dirty children. The boat itself impressed this romantic young man as splendid and comfortable. He was especially pleased by the food and admitted he loved eating. Breakfast consisted of ham, eggs, steak, sausage, hot cakes, and plenty of good bread. Dinner offered roast beef, mutton, veal, turkey, goose, plus pies and puddings. Shooting the falls at Louisville was less pleasant; it was an ugly part of the river, he thought, and boats went wildly down the boiling chute. Other passengers, however, were excited by the wild ride.

About two years after Whitman's trip, a German visitor to America, Moritz Busch, recorded his dining experience on an Ohio River steamer. The tables were covered with dishes of fruit, vegetables, jelly molds, meats, cakes, biscuits, and breads. The men stood behind their chairs. The main course, generally a large roast of beef, was placed before the captain, who would preside as host to the passengers. The bell was sounded for the ladies to enter and take their seats. The meal was a bountiful and even a noble experience although no one in the cabin was an aristocrat. In fact, not long before the meal was served, most of the passengers were demanding that the captain race the boat running ahead of theirs. The captain at first ignored these insane demands, but finally ordered the engineers to make all speed possible. Bets were set up, and the fireman worked furiously to make more steam. After an hour the steamer was just behind its rival. Shouts and cries went up, but as Busch's steamer passed the other boat, it proved to be another vessel, not the one named in the bet. Too often racing ended in an explosion; fortunately, this one resulted only in a few red faces.

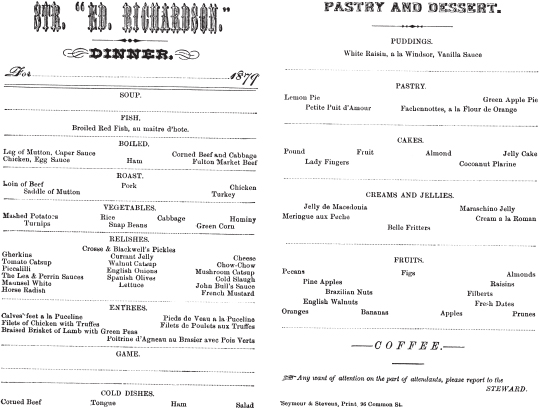

In 1846 Sir Charles Lyell, professor of geology at Kings College, toured America. He started his journey in New Orleans on board the steamer Rainbow but switched to the Magnolia at Natchez. The Magnolia was a large boat built for the lower Mississippi. She was a fashionable vessel and a favorite with society ladies and bridal parties. The captain was French and was fond of rich food, especially roast duck. Professor Lyell noted that the menu was sumptuous and included soup, two kinds of fish, a chain of entrees, and desserts. The claret was excellent, but Lyell was puzzled why some guests quaffed down river water. It was cloudy and full of tiny particles and silt, yet those consuming it declared it was healthy and drank it as a physic. Other travelers spoke of other boats where the food was well cooked and carefully served. The waiters stood by like bronze statues. A few boats kept a cow on board for fresh milk. Many had a henhouse on an upper roof. All stopped to pick up fresh food en route. Some boats offered a third seating to deck passengers who were willing to pay for a meal. Printed menus were common on the better boats (fig. 7.7). Special meals were prepared for visiting dignitaries. The menu for a breakfast served to General Ulysses S. Grant on September 3, 1865, included soft-shell crab, lamb chops, and prairie chicken. One of the notable and unusual characteristics of riverboat menus was the absence of prices. This is because meals were served “free” to first-class passengers. At least no money was collected at mealtime, but of course the cost was buried in the overall fare. Gerstner estimated the costs were about $1 a day, so if the trip lasted six days, the steamboat operators add $6 to the fare.

7.7. This menu was used on the Ed Richardson, a large Mississippi packet built at the Howard Yard in Jeffersonville, Indiana, in 1878.

(G. L. Eskew, Pageant of the Packets, 1929)

Most of the profit in the steamboat business came from the freight carried on the main deck; however, boat operators added to their revenue by carrying second-class passengers on the same deck. While a very few boats offered rustic wooden bunks, none included mattresses or bedding. In most cases, deck passengers looked for an empty place among the barrels and boxes. Emigrants, flatboat men heading home, farmers, and any poor person needing a cheap ride went as deck passengers. One such traveler was Andrew Carnegie's father, a hand weaver whose dyeing trade paid so poorly he could not afford a cabin. Andrew and his father traveled on the same boat, but only the younger Carnegie could afford a first-class ticket.

The lower deck was a scene of filth and wretchedness, but the fare was cheap, just $1 to go from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati. At less than a penny a mile, the riverboat was about the cheapest way to travel anywhere in the world. There might be 150 passengers on the deck, making sleeping space scarce. Dinner would consist of items taken on board by the travelers, such as sausage, dried herring, cheese, bread, and whiskey. A few boats sold food to deck passengers, but at 25 cents most would decline the offer. Sleeping on the freight deck could be dangerous. Cattle, sheep, and hogs were loaded and unloaded at stops along the way, which could include early morning hours. Sleepers might get trampled by the exiting animals. It was possible to roll over and drop off the deck into the river. Some passengers simply lost their balance and dropped over the side to drown in the muddy water. Some travelers were in good spirits despite the primitive accommodations. They were traveling to a new home in the west, where rich soil and cheap acreage promised them a better life in the new world.

Not all river travel was made on the three major branches of the inland rivers. Travelers patronized smaller boats that plied the Cumberland, Arkansas, and Illinois Rivers and dozens of other tributary streams. A college student named Theodore Hibbett was returning to his home in Nashville in June 1852. His previous experiences with stagecoach travel prompted him to try a river trip. For $10 he could go from Cincinnati to Nashville. The Jenny Lind was scheduled to follow the Ohio River to the mouth of the Cumberland River, which is about a dozen miles east of Paducah, Kentucky. There was only one boat a week between the two cities. Steamboats had been following this winding river 193 miles to Nashville since 1818. It was never an easy passage, especially in the dry season. By the fourth day the Jenny Lind started up the Cumberland River. There had been delays all along the Ohio River due to fog, sandbars, and a broken pump. As they proceeded, the water level dropped to 18 inches. The captain stopped and ordered the removal of cargo to lighten the vessel. Late that night they started up the Cumberland again, but by 10:00 the next morning, the boat was hung up on a sandbar. The captain resolved to return to Cincinnati. Once free of the sandbar, Hibbett got off rather than backtrack. He hoped to take a stagecoach or another boat to Nashville. A very small boat appeared at 1:00 AM and tied up because of fog. Hibbett bought a ticket as a deck passenger, because all the cabins were full, and sat up for the rest of the night.

The Jenny Lind proceeded at sunrise, rarely going faster than 2 mph and stopping to pick up more passengers for this already crowded boat. Even more passengers were added from a stranded boat. It was extremely hot, and there was only river water to drink. The cabin smelled so vile that Hibbett could not think of eating. The mosquitoes were as thick as a swarm of bees. This day was pure torment, and the following night was the longest he could remember. Five days out from Cincinnati, they had reached Clarksville, Tennessee, and were still more than 50 miles from Nashville. The boat continued to battle its way over shoals. After two or three tries, the deckhands would wade up the river to pull the boat by ropes. By early afternoon of the sixth day, they were within sight of Nashville, but it took almost three hours to get the boat around an island. What an exhausting and uncomfortable journey! Hibbett must have wondered if steamboating was so superior to stagecoach travel after all.

7.8. The Benton was a typical Missouri River mountain boat designed for light draft service. It was built in 1875 for T. C. Power and Brother's “P” line of steamers. Notice the spars attached to derricks at the bow. These sturdy wood poles were used for grasshoppering across sand or mud bars on the Upper Missouri River.

(James Rees and Sons Company Illustrated Catalog, 1913)

A few years after Hibbett's misadventure, Frederick L. Olmsted traveled as a correspondent for the New York Times. He was on his way to Texas and wrote a series of articles about his journey. Olmsted retraced the exact path that Hibbert's boat had taken. Low water was again the problem, but matters went more smoothly for Olmsted. The captain of the D. A. Tomkins promised to reach Nashville in a day, but the trip took about four days. The boat had hardly started on its way before a snag damaged the paddle wheel. After the repair was completed, a fog settled in, so they did not proceed. The following day they passed another boat abandoned on a sandbar. Upstream several other large boats were unable to move because of the low water. The D. A. Tomkins was a little vessel with a small draft. When a low place was encountered, the freight was transferred to barges tied onto either side of the mother boat. This lightened her load enough to go forward. In other places, spars were planted in the river bottom at the boat's bow. She was lifted upward a few inches by a windlass, on these timbers that acted as crutches. The paddle wheel, working at top speed, would propel the boat forward and over the sandbar. This method was much used on the Missouri River and was called grasshoppering or walking the boat (fig. 7.8). It had been in use since the 1820s. On the nearby Tennessee River, boats were helped upstream by large shore-mounted capstans. The manually powered capstan ropes attached to the boat and pulled the vessel upstream.

In general, Olmsted found traveling the Cumberland River more boring than unpleasant. The scenery remained monotonous, with a steady line of drooping tree branches and uncleared land. The boat engine's exhaust kept up a steady choosh, choosh, choosh that could be heard for miles. This, too, Olmsted found to be tiresome. He was happy to return to the Ohio River and continue his travels on a full-size, mainline river. The Cumberland River was much improved by the early twentieth century with locks and dams, canalization, and deepening the shoals. Light draft boats, at 30 inches deep or less, could reach Nashville year round, but larger steamers drawing no more than 36 inches could operate for only six to eight months. Eventually navigation was opened to Burnside, Kentucky, 518 miles upstream from the river's mouth on the Ohio River.

The headwaters of the Monongahela River are in southeastern West Virginia. The narrow stream winds its way northward into Pennsylvania and joins the Allegheny River at Pittsburgh to form the Ohio River. Steamboat navigation began in 1825 between Pittsburgh and Brownsville, Pennsylvania, a distance of 35 miles. However, service could be maintained only when the water level was sufficiently high. A private corporation was organized to improve the river so that boat service could be maintained year round. Rather than beg for public funding, the Monongahela Navigation Company was established to do the job. Instead of wasting years hoping for state or federal subsidies, this company went to work. By 1844 several locks and dams were completed, creating a series of pools or lakes and allowed year-round steamboat service. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had reached the Cumberland by this time. A stagecoach line connected Cumberland, Maryland, to Brownsville. This part of the trip was just 73 miles. The entire journey from Baltimore to Pittsburgh required just thirty hours, which was considered a very fast time in 1844. Passengers arriving in Pittsburgh had a choice of numerous steamers leaving for ports as far away as New Orleans. This multi-mode route to the West proved popular for about eight years; the northern end of the Monongahela teemed with passenger traffic. In 1847 the local packet line carried 445,825 through passengers and 39,777 way passengers; even more were transported during the next year. By 1852 the Pennsylvania Railroad opened its line to Pittsburgh. Riverboat passenger traffic fell off dramatically that year. It was quickly reduced to local or way passengers. Freight traffic on the Monongahela continued to grow. Millions of bushels of coal went to market on this small tributary river. More dams and locks extended commercial navigation to Morgantown, West Virginia, in 1904. Many other secondary steamers in the inland river system also offered steamboat service during the Victorian era.

MORE DANGEROUS THAN A SHIP AT SEA

In 1851 the Irish Emigrant's Guide to the United States claimed that steamboats were “more dangerous than a ship at sea,” and in January 1864 the American Railroad Journal offered transportation statistics for the years 1853–1863. Steamboat accidents were responsible for 3,545 deaths compared to 1,699 deaths on railroads. The exactness of these statistics might be challenged, but it is a fact that the riverboat industry had a poor safety record and thus was perceived by the public as a dangerous means of travel. The U.S. Congress reacted to public complaints in 1838 by enacting a steamboat safety act. It proved to be little more than a gesture, however, because little funding was appropriated to enforce the law. In 1852 a second bill was passed that included money for inspection and enforcement. A list of riverboat accidents was compiled in that year. It was a historic survey covering the years 1811 to 1851. The data was gleaned from available sources – notably, newspaper accounts – and is likely incomplete, yet the total of 995 accidents remains alarming. The greatest cause of accidents was snags at 57.5 percent. Boiler explosions were a poor second at 21 percent, and the remaining 21.5 percent was divided between fires and collision. The number of lives lost from all causes was just a little over 7,000.

Snags were the great sinkers of riverboats. In terms of property damage, they proved the greatest hazard, particularly before a systematic removal service was established. Relatively few passengers died in the resultant vessel loss, because the boat was often beached on the riverbank before the sinking occurred. At times of low water only the first deck was submerged and the passenger deck remained above the river. In such cases it was safe for the travelers to remain abroad until rescued. Boats could go down quickly, especially if the snag was large and hit the bow. This happened to the Arabia in September 1856 on the Missouri River near Kansas City. The snag was a large walnut tree that was both heavy and tough. The Arabia sank in just ten minutes, but the only fatality was a mule. In 1988 work began at the wreck site to recover the cargo and parts of the boat for display in a museum in Kansas City.

Not all sinkings resulted in tragedy; some were harmless and even somewhat amusing as this story about the Messenger illustrates. She was a nearly new side-wheeler on her third trip to New Orleans from Cincinnati. It was around suppertime on August 13, 1866, and the boat was moving along the Mississippi River with a barge attached on either side. It was proceeding below Island Number 26 and was about 55 miles north of Memphis when the bow struck a submerged tree stump. A good-size hole was made and the boat sank in ten minutes. One of the loaded barges broke loose from its lines and floated downstream. The second barge was empty. It stayed alongside and the passengers and crew climbed aboard it as a precaution. The stump, firmly implanted in the riverbed, supported the front end of the Messenger while the rear of the boat sank in shallow water. The main deck was flooded by just 6 feet. Seeing that all was safe, everyone climbed back on board. Dinner was served and proceeded normally until the limber structure of the vessel began to settle into the soft mud at the river's bottom. Just an inch or two of settlement caused the hull and cabin to pop and crack. These sounds so unnerved one young man that he jumped up on the dining table to escape what he perceived was a sudden danger. He collided with an overhead lamp and broke the glass shades and chimneys. The broken glass hit the table, setting off alarm among the diners. When it was explained that these cracks and pops were normal sounds that were sure to continue, the dinner proceeded. The passengers returned to their sleeping cabins. The next morning another boat stopped by and took aboard all who wanted to go upstream. Later, a second boat rescued those wanting to go downstream. The boat was raised, repaired, and continued in service until 1875.

A snag could also result in a tragedy, however, as was true of the Belle Zane one cold January night in 1845. She struck a snag on the Mississippi River below the mouth of the White River in east central Arkansas. The collision was so violent that the boat rolled over. The passengers were in bed, and only about fifty of those on board managed to escape from their berths. Of these, only sixteen survived that bitterly cold night. Some of the bodies were buried along the riverbank.

Fire was far more lethal because of the flimsy nature of the upper cabins and the boat's inflammable nature. Smoking, open-flame lamps, and heating stoves all contributed to the fire risk. Boats burned individually or in groups. There was a mass burning of steamers along the Cincinnati Public Landing in the early morning of May 12, 1869. The fire is believed to have started in the nursery of the steamer Clifton. By 2:00 AM it had spread to five other vessels, sending flames 100 feet into the sky. Fortunately, the passengers had departed some hours earlier and only the death of one employee was reported. Two other boats escaped by backing out into the river and out of harm's way. A second major fire occurred in the same place in 1922. Once again, several steamers were destroyed as the flames spread from one boat to the next. The origin of the fire was a large container of roofing tar being heated on a galley stove. A much larger riverfront fire started in St. Louis innocently enough in May 1849. Chamber maids had put bedding out to air. Sparks set it on fire around 10:00 PM. The flames spread to other boats and nearby buildings. In all, twenty-three steamers were destroyed as well as many blocks of the warehouse district.

Fire accidents on riverboats sometimes involved the loss of human life. The Ben Sherrod was on her way to Louisville when she began to overtake another boat upstream. It was 1:00 AM on May 8, 1837, and most passengers were fast asleep in their cabins. The crew decided it would be fun to stage a race. They provided the fireman with a barrel of whiskey as a reward to stoke the fireboxes full of wood, pine knots, and rosin. The boilers supplied steam in ever-increasing amounts to push the vessel faster against the current. The cord wood was stacked next to the overheated boilers and caught on fire. The smoke began to wake the passengers, but it was too late for an orderly evacuation. Many jumped into the river; a lucky few found a barrel or some driftwood to sustain them. Two passing boats drew alongside to rescue some of the passengers. Of the three hundred on board only about half survived.

A much less deadly fire consumed a stern wheeler named the Iron Queen near the small town of Antiquity, Ohio, in the spring of 1895. If everyone on board had followed the captain's orders, the blaze would have claimed no one. Passengers had gathered in the cabin for breakfast. Roustabouts were loading cargo on the lower deck when one of them accidently knocked over a lantern. It fell behind some crates and smashed on the floor, starting a small fire. No one noticed the flames until the fire had grown too strong to extinguish. Everyone was ordered off the boat. A chambermaid named Mattie Mosby could not bear the thought of being seen in public without her hat and impulsively ran back on board to retrieve this precious item. Once on the burning boat, however, she was unable to make it back to shore. Trapped by the flames, she jumped into the river and drowned. It was a sad and unnecessary death.

Riverboats were considered floating volcanoes that were likely to self ignite. The Pacific proved the validity of this saying while taking on coal at Uniontown, Kentucky, in November 1860. The pine-knot basket torches were the common form of lighting used to illuminate the first deck during any nighttime loading event. One of these medieval torches set the boat on fire – she burned to the waterline and killed eight people.

Collisions were another hazard that destroyed boats and their human cargo. The Thomas Sherlock was leaving for New Orleans in February 1891. It was early evening but the sun had already set. The boat backed into the river and made ready to swing around and head south. The current was very strong that evening – it carried the boat downstream faster than usual, and before the pilot could swing her around, the boat ran into a bridge pier with a mighty crash. The smokestacks collapsed and the upper works separated from the hull. The cabin floated downstream with thirty passengers and some of the crew. The wreckage traveled 10 miles before another boat could push it back to shore. Only two people died in this extraordinary accident, which indicates that the upper works or cabins could hold together well enough to carry all but two safely downriver.

Collisions between boats were common enough and often involved only minor damage. The collision of the United States and the America on the evening of December 4, 1868, was of a more serious nature. Both vessels were owned by the U.S. Mail line that offered overnight service between Louisville and Cincinnati. Both were large, deluxe packets of recent construction. The night was windy but clear, and the boats met near their normal passing place, two miles below Warsaw, Kentucky. On this night, however, a substitute pilot was at the wheel of the America. The regular pilot kept toward the Kentucky shore when going upriver while the down boat stayed toward the Indiana shore. In violation of custom, the substitute man decided to cross over to the Indiana shore. He signaled his intention to do so, but the pilot on the down riverboat, the United States, responded so quickly to the signal that he drowned out the sound of the second whistle blast. The America cut across the stream and slammed the United States amidships. The collision knocked down many passengers and toppled over a cargo of oil barrels. Fire broke out on both boats. Passengers and crew members scrambled to get off both vessels, which were burning and sinking at the same time. Estimates varied between 63 and 170 deaths. Many were injured. The America was a total loss, and the United States was heavily damaged. This terrible accident was the result of a misunderstanding of the whistle signal, demonstrating that small mistakes can result in tragic consequences.

Boiler explosions were a leading cause of deaths for riverboat travelers (fig. 7.9). In 1852 it was estimated that one-half of steamboat deaths were the result of such explosions. Higher steam pressures resulted in greater power but at the price of safety. Racing led to over-firing that taxed the wrought-iron boilers of the time; this, too, resulted in explosions. Careless and reckless management on the part of the engineering crews also led to failures. A fireman on a Mississippi steamer was quoted by a traveler in 1844 as saying, “But I tell you, stranger, it takes a man to ride one of these half alligator boats, head on a snag, high pressure, valve soldered down, 600 souls on board and in danger of going to the devil.” Many innocent travelers were blown to the devil by such men. In April 1838 the new steamer Moselle was ready for her second trip to Louisville. Her captain ordered the engineer to produce the maximum amount of steam so that his fine new boat would make a speedy pass along the Cincinnati riverfront and impress everyone who saw her leave port. The safety-valve levers were laden with extra weights. The boat was packed with passengers, including a large number of German immigrants. Before her wheels had made a single turn, there was a tremendous roar and the boat disappeared from view in a cloud of steam and smoke. Pieces of wood and iron fell from the sky into the river and on the nearby shore. Bodies and parts of bodies rained down as well. Of the estimated 280 on board, around 150 were dead or missing. Only a week earlier, the Oronoko had blown up on the Mississippi River, resulting in about 100 deaths.

7.9. The steamer Magnolia blew up and burned on the Ohio River several miles above Cincinnati on March 18, 1868. It was not a major disaster, yet thirty-five lives were lost.

(Harper's Weekly, April 4, 1868)

The U.S. Congress passed a steamboat inspection law in 1838 that temporarily quieted the public alarm over the issue of riverboat safety. However, the bill was far too general in its wording; it did not provide for meaningful inspections and was largely ineffective. In 1852 a much more specific federal act was passed, which included detailed provisions for boiler and hull inspections. Engineers and pilots would now be tested and licensed. Meaningful results were soon evident. Between 1848 and 1852 there were 50 major accidents and 416 boiler explosions, resulting in the loss of 1,155 lives. Between 1854 and 1858 there were 20 accidents, 214 boiler explosions, and the loss of 224 lives. Despite this general improvement in safety, the accident rate increased during the Civil War years, because boats and men were being worked very hard and maintenance tended to be neglected because of the war emergency.