N 9

9

Coastal & Sound Steamers

Close to Shore

THE ATLANTIC SEACOAST WAS THE GREAT HIGHWAY OF COLOnial America. Small ships sailed over these waters from Maine to Florida, stopping at dozens of ports or inlets. The sinking eastern coasts of North America formed numerous natural harbors, inlets, sounds, and bays, all of which encouraged maritime travel. Some boats ventured no more than 100 miles from home while others sailed the length of the coast to New Orleans. Even more adventuresome sailors would circumnavigate South America and head for San Francisco. Such ambitious sojourners covered 14,000 miles in 180 days. Yet most coasters were content with more modest travels and engaged in transfer trade. They would stop at several small ports to gather shipments for oceangoing vessels. The coaster would transfer goods to larger ports where the cargo would be loaded upon a ship heading for Europe or the Far East. In the same way, they would distribute goods or passengers, dropping them off at large ports by the sea to hamlets on the coast. A typical merchantman would take six to ten days to sail from New York to Charleston, a distance of approximately 650 miles. Small sloops were faster, but they could carry only limited cargoes and so were more often used for shorter commuter trips. Steam power offered both speed and capacity, and by the 1830s it began to offer passage between Charleston and New York in three days. Travelers to New Orleans could expect more than a dozen days at sea, often leaving New York by steamer. Such a journey could be pleasant as long as the sea was reasonably calm.

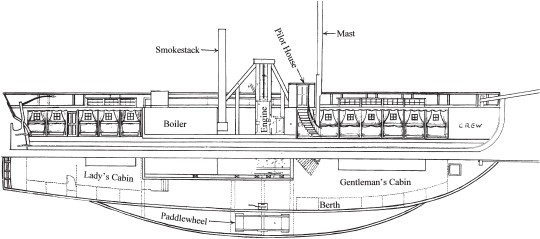

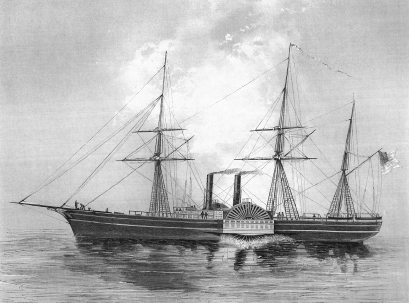

9.1. The Fulton was completed in 1813 to the design of Robert Fulton. Because of the War of 1812 it did not enter Long Island Sound service until 1815.

(Jean-Baptiste Marestier, Marestier's Report on American Steam Boats, 1824)

Sailing close to shore meant the ship could seek protection in a harbor, bay, sound, or river. The eastern seacoast offers many such harbors. On the other hand, being so close to the shoreline meant a storm could drive ships onto a reef or rocky point that would send it to the bottom. Locals along the coast made their living by salvaging wrecked ships, and it seemed that every few weeks nature landed a pile of treasure near their front yards. The wrecked ships and their cargo were a rich store of building material, food, and trade goods, so salvagers were opposed to lighthouses and other navigation safeguards that would end their trade. The best sailing season along the coast was April to November, but there was always the danger of a storm blowing in; these events were almost always a surprise, because there was no weather forecast available. Sea captains kept an eye on the sky to seek some indication of what might be developing.

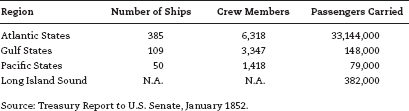

Table 9.1. U. S. Steam Navigation, 1851

Pirates were yet another danger along the North American coast because of so many well-laden vessels traveling along this busy trade route. It was said that a person could stand at the coast and see as many as six boats passing at a time. The British navy did a poor job of defending the merchantmen, because they had too many assignments elsewhere in the world. The empire was growing, and His Majesty's service was well engaged elsewhere. During the Revolution and the War of 1812, American shipping became prey to the British fleet. Once these hostilities were concluded, the pirates returned and were not subdued by the U. S. Navy until the 1830s.

Traffic along the coast was stimulated by the growth of population in eastern cities and the expansion of industry in young America. Manufacturing was discouraged under colonial rule. America was to supply raw material to the mother country and import her manufactured goods, but since independence all of that had changed. Industrial towns such as Paterson, New Jersey, were established as early as the 1790s. A cotton mill was set up in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. This meant cotton was transported from the north for New England's textile mills. Molasses came in great drums from Havana and the sugar islands to be processed into sugar and rum. Shipping lines were being established on Long Island Sound; Chesapeake Bay; and the James, Potomac, Delaware, and Hudson Rivers, which fed more travelers and cargo to the coastal ships. In 1888 John Ringwalt estimated that one-half to three-quarters of all American shipping was coastal. Because Britain so clearly dominated world shipping, America concentrated on the coastal trade; however, the country's transatlantic lines tended to be short-lived or feeble. In 1817 the U.S. Congress passed legislation that closed coastal shipping to foreign ships. This protective law would create a nursery for seamen and thus strengthen one branch of the country's marine industry. In 1845 Congress acted again by offering mail subsidies for maritime carriers. The payments were not generous but large enough to encourage the expansion of shipping lines by river, lakes, and seas. The effect was to support new steamer lines to Charleston, Savannah, Norfolk, New Orleans, Havana, and elsewhere.

Table 9.2. U. S. Steam Navigation, 1880

Statistical information on U.S. shipping is difficult to assemble other than data on freight tonnage. However, tables 9.1. and 9.2 provide some idea of steamship activity for 1851 and 1880. (Data for lakes and inland rivers are reported elsewhere in this book.)

LONG ISLAND SOUND

Daniel Webster once referred to Long Island Sound as the “Mediterranean of the western hemisphere.” It was the busiest corridor for passenger vessels along the East Coast. Although it generally appears placid and is protected by Long Island from the Atlantic Ocean, the sound is part of the ocean and is just as salty and treacherous. It is about 100 miles long and as wide as 30 miles. It has many fine harbors and inlets with a dozen midsized towns. Of more importance, it connects New York with Boston. It would do so directly were it not for Cape Cod. The way around this barrier is an overland portage from one of the coastal cities, such as Fall River. Such travel was initially made possible by stagecoach connections, and by the late 1830s by a series of railroads radiating from Boston.

Nature created a few more defects to travel through the sound. The entrance from the East River at the New York end is hampered by the connecting channel, purposely named Hell Gate, which is short but narrow and rocky. Worse yet, it has two tides – one from Long Island Sound, the other from Sandy Hook. The tides collide at Hell Gate and create whirlpools that pitch small ships around and over the rocks and reefs. It was said in those days that for every fifty ships passing through Hell Gate, one was seriously damaged. In 1851 work was started to remove some of the rocks; more work was done over the next several decades, and by 1885 Hell Gate had lost much of its bite. The channel was 26 feet deep and 200 feet wide at its narrowest place. At the other end of the sound is Point Judith, standing at the lower tip of Rhode Island and the entrance of Narragansett Bay. The problem here is not rocks so much as the confused currents that come together from the sound, ocean, and the bay to produce a swirling merry-go-round that can drive ships against the point. A Stonington Steamship Line advertisement referred to Point Judith as a “dangerous promontory” where waves rose in a fearful violence, making passage, if not always dangerous, at least unpleasant to persons unaccustomed to life at sea.

Sloops carried passengers and household goods along fish-shaped Long Island in colonial times. Large and slower vessels carried the freight. British patrols during the War of 1812 delayed the testing of steam vessels for a few years, but Robert Fulton built an elegant little steamer especially for such service in 1813. She ran on the Hudson River until the British withdrew. Figure 9.1 shows a cutaway drawing of this vessel, named the Fulton. She measured about 134 feet long and had the boiler and engine in the center of the vessel. Two-tier bunk beds were built in the cabin. Draw curtains made them into a private compartment. A small cabin at the stern was reserved for ladies. Both cabins had a skylight. The crew slept in the forecastle. She made a trip to New Haven in March 1815; this 75-mile trip took eleven hours. Later she ran to Hartford and Norwich, Connecticut. Her normal running speed was 6½ mph, and her cost was $87,000.

Fulton built a similar boat for service in Russia in 1816, and when the promoters of this venture failed, the vessel was renamed the Connecticut and put into operation with the Fulton. The little Firefly had been tried a year later on a run between New York and Newport, Rhode Island. She was much too slow to win many admirers, taking twenty-eight hours to finish the trip. The packet sloops could outrun her with a favorable wind. They also dropped their fare to 25 cents and sent the Firefly into an early retirement. Fulton's reputation was vindicated several years later by the performance of his last ship, the Chancellor Livingston. This vessel was completed nearly two years after the designer's death in 1814. She provided good service on the Hudson River by running at 8½ mph and consuming 1½ cords of wood per hour. She was rebuilt with new machinery in 1827 and put into sound service. There she ran three round trips a week between New York and Providence. In 1832 the Livingston began the Providence-to-Boston run. Two years later the aging vessel was running between Boston and Portland, Maine.

Meanwhile Fulton's steamboat monopoly had been overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court as an unconstitutional violation of interstate commerce. Only New York and part of Louisiana had agreed to the Fulton and Livingston monopoly. Elsewhere steamboats were operating freely and could run at will through all of Long Island Sound. Many independent operators were contemplating a monopoly of their own by setting up powerful lines of steamers owned by wealthy partners or corporations. Cornelius Vanderbilt was one such operator. Vanderbilt had already made a small fortune from Hudson River boats, so an expansion into sound steamers was only natural. He was not a gentleman in manner or speech, but he was smart, bold, and cunning. He also liked to win. In 1835 Vanderbilt decided to build a sound boat that would win greater traffic for his operations and put his rivals to shame.

The Lexington was the commodore's pride. He had personally supervised her construction. She was framed with the best white oak for strength. At 205 feet, she was long and elegant like a racer. In June 1835 she began service between New York and Providence and made the round trip in twelve hours and twenty-eight minutes. Her average speed was over 12 mph, which was a record. A New York newspaper declared her the fastest steamboat in the world. Vanderbilt was happy, and when she hit a reef sometime later at 16 mph and revealed no damage, he was even happier. The Lexington performed well in regular service, making three trips a week. The fare was $4, with meals available at an extra charge. The Lexington was sold to the Stonington line in part because they offered a good price, and Vanderbilt was always ready to build a new and faster boat. However, the Lexington did not go quietly in the night.

The Lexington operated on the Stonington line without apparent incident until early 1840. She left New York at 3:00 PM on January 13 of that year bound for Stonington, Connecticut. The line called itself the Great Inside Route because Stonington was just to the east of Point Judith, and passengers could relax knowing they would be spared that hazard. The Providence and Stonington Railroad opened a 93-mile-long rail connection to Boston in 1837 that ranked next to the Fall River line in popularity. The Lexington steamed ahead in what promised to be another routine trip. At almost 7:00 PM flames were seen near the smokestacks. Some of the cotton bales stacked all around the boat were on fire. Captain George Child seized the wheel and headed for shore. They were 3 or 4 miles below Eaton's Neck, Long Island, or roughly opposite Norwalk, Connecticut. A fresh wind fanned the flames. Soon the tiller rope was burned in half. The lifeboats were either swamped by overcrowding or were smashed by the paddle wheels. About 150 people on board were killed by the fire or the frigid water of the sound. Four saved themselves by clinging to cotton bales. One of the swimmers floated in this uncomfortable position for two days. The New York Sun heralded this major news story by issuing an EXTRA with a lithograph on the front page depicting the horrific scene of flames and death. Nathaniel Currier, an obscure printmaker, furnished the lithograph and continued to sell it for another eleven years. No longer obscure, Currier would become more famous in later years as a partner of James Ives.

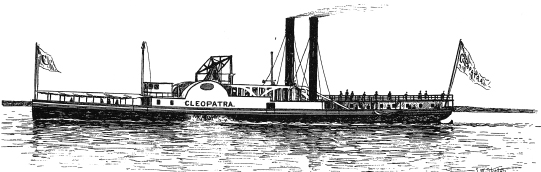

9.2. The Cleopatra was built in 1836 for Cornelius Vanderbilt and was used on Long Island Sound. Her two boilers were made of copper.

(Samuel Stanton, American Steam Vessels, 1895)

Not all of Vanderbilt's sound steamers met a violent end. The Cleopatra had a long and peaceful life. She entered service in 1836 on the New-York-to-Hartford run. Her long and low look was typical for most of the early sound steamers (fig. 9.2). After a few seasons she was assigned to the Providence, Norwich, and New York run. In 1845 Vanderbilt opened a railroad to the end of Long Island at Greenpoint, New York. A dock was built, and steamers such as the Cleopatra carried travelers to Providence and other sound ports serviced by the Vanderbilt lines. Travel time was reduced and those passengers in a hurry patronized the Greenpoint line. The Cleopatra, unlike her ancient namesake, went out quietly. She never wrecked, burned, or blew up but worked out her last day as an excursion boat in New York Harbor.

George T. Strong (1820–1875) recorded a diary account of his trip on the sound steamer Massachusetts dated May 5–7, 1836. Strong was a student at Columbia and was taking a trip to Boston with his father. He booked two berths at the dock and then walked uptown to St. John's Park, where he sat on the grass and visited with a classmate. The next day he left school and went directly to the dock. The Massachusetts was a new boat and much like the Lexington in size. She had space for 142 berths. Strong estimated there were one hundred people on board. She made her first trip to Providence in thirteen hours and thirty-two minutes. The cabin was in the hold, as was typical of the time, and well fitted out, she cost over $100,000. The trip had not been under way long when they came up to another steamer, the President, which was unable to move because of a broken paddle wheel. The Massachusetts stopped and took on some of the stranded passengers, which took almost an hour.

Strong got a cup of coffee, walked forward, watched the sound, then went below to read, and at nine he adjourned to his berth. It was narrow but better than the temporary beds set up for the President's passengers. He found sleep difficult – perhaps too much coffee, the motion of the boat, or the serenade of snoring around on all sides kept him awake. At five the next morning he was summoned by his father to go up on deck to witness the specter of Point Judith. For all of its terrible reputation, it looked very placid through the fog. They passed Newport, which Strong described as mean and contemptible looking, then sped up Narragansett Sound, where our young traveler judged the great city of Providence as worse in appearance than Newport. They arrived at a little after 8:00 AM and proceeded directly to the railroad. Strong had never ridden before on a “decent railroad” and wondered about the effects of a fast ride. They were now clicking along at 25 mph, which was very rapid traveling for 1836, yet our cavalier New Yorker perceived no danger or fear. They arrived in Boston at 10:15 AM in perfect condition except for a copious sprinkling of dust. And here our firsthand account of travel in 1836 ends.

Several boat lines were operating on the sound by the 1830s. There were also many independent boats in service, so Long Island Sound was a busy waterway filled with steamers and sailing vessels moving in all directions and patterns, yet taking care never to collide. In 1847 another new line would start up to make the busy waterway more crowded. It began as the Bay State Steamboat Company but would evolve into the famous and long-lived old Fall River line. In 1869 it was merged into the Narragansett Steamship Company by James C. Fisk, the Wall Street speculator. After Fisk's murder in 1872, it was reorganized as the Old Colony Steamboat Company, a subsidiary of the Old Colony Railroad. When that railroad was absorbed by the New Haven Railroad in 1893, its steamboat properties were added to New Haven's New England Navigation Company. This last combination was part of an ambitious scheme by J. P. Morgan to assemble all of New England's public transportation into one company. It would be efficient and would benefit both stockholders and the public. Morgan was a brilliant and able man, but this proved to be one of his mistakes. The Fall River line would remain part of the New Haven Railroad's empire until its final days of operation.

The Fall River line began with just two boats, the Bay State and the Empire State. The Bay State was 317 feet long and 82 feet wide. Her wheels were 38 feet in diameter and 10 feet, 3 inches wide. She made a run from New York to Fall River, including a stop at Newport, in eight hours and forty-two minutes and became known as a sound flyer. Two boilers sat on the guards on either side of the hull. These low-pressure vessels burned 6,500 pounds of hard coal an hour. This hot-burning fuel produced very little smoke. A correspondent for the Illustrated London News reported on a visit to the Fall River dock in April 1852, saying that the interior of the Bay State offered every comfort and luxury a passenger could hope for – rich décor, damask curtains, excellent food, a fine upper deck to view the scenery, and a saloon and cabins that approached splendor. But upon examination of the lower deck the reporter found a large open warehouse suitable for rough cargoes. It was here the immigrants were sent to find a place among the boxes and barrels or perhaps a soft plank in the floor. It was a picture of misery. The reporter noticed that at the end of the trip the hot coals and cinders were raked out of the boiler's firebox directly into the river. A huge flag at the stern of the boat at least 30 feet long read, “Bay State.”

9.3a & 9.3b. The Old Colony dating from 1865 experienced an unfortunate engine failure in 1878 when one end of the walking beam fractured and crashed through the vessel's cabin. There were no injuries to crew or passengers.

(Scientific American, May 25, 1878)

The Empire State was somewhat newer than the Bay State and was equally elegant. An English woman traveler, Marianne Finch, recorded a tea aboard this big side-wheeler in 1848. It was held in the main cabin on a long table covered with everything beautiful and edible. There were pineapples, butter, tea cakes, pies, tongue, ham, and all kinds of delicacies served by waiters in white linen uniforms. At the end of the banquet a waiter whispered in passengers’ ears “half a dollar.” A coin was produced and silently disappeared, not a clink was heard. For all of its refinement of service, the Empire State was not a particularly lucky ship. She suffered a boiler explosion, a fire, and two serious groundings in her twenty-three years of service. The Bay State was better behaved than the Empire State and ran until 1864 with no major problems. She was lengthened in 1854 to 352 feet. Her engine was removed and placed in a successor named the Old Colony. These old beam engines were hard to wear out, so reuse was commonplace. The old engine performed well for many years in the second boat until one day in 1878 the walking beam, the top of which was about 45 feet above the keel, cracked in half. This massive piece of iron, together with the connecting rod, crashed through a partition and stairway, landing on the keel; fortunately, no one was injured. The fact that the beam did not break through the keel saved the boat. A defective forging was likely the cause of the rupture. The good luck of the old Bay State had apparently carried over, for the accident could have caused a disaster (figs.9.3a and 9.3b).

Sound boats of the 1850s continued to grow in elegance and comfort. The Commonwealth of 1854 cost $250,000 and was the standard-bearer for a time in terms of style and finish. After just eleven years of service she burned at Groton, Connecticut, and was deemed a total loss. The Metropolis combined beauty with speed, and in June 1855 she made a trip from Fall River to New York in eight hours and fifty minutes, averaging 20 mph. She steamed on until 1879. American steamers of the time were seen as splendid and glittering, all white and gold on the outside and grand and elegant on the inside. As more decks were added to make them taller, steamers took on a regal yet top-heavy look. But make no mistake, they could cut through the water like a swordfish.

9.4. The Bristol of 1867 was one of the largest and most decorative sound steamers of her time. She was 375 feet long and had 1,200 berths.

(Asher and Adam's New Columbian Railroad Atlas, 1887)

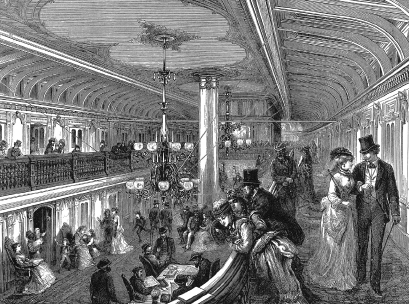

James Fisk Jr., also known as Admiral Fisk or “Jubilee Jim,” had been involved in Wall Street investments for many years, but he found steamboats an attractive business, a way to both emulate and annoy Commodore Vanderbilt. In 1865 he purchased two large sound steamers: the Bristol and the Providence. They were designed and built by celebrated naval architect William H. Webb. The boats were outfitted with rosewood doors, a mahogany stairway, velvet pile carpets, gas lighting, and steam heat (figs. 9.4 and 9.5). At a cost of $1.25 million each, one would expect some luxuries. Fisk added his own touches, too, such as a lavender trim to the paddle boxes, deep yellow for the smokestacks, and 250 gilded birdcages complete with yellow canaries. He dressed the ships’ officers in overly elaborate uniforms, with the most ostentatious admiral's uniform for himself. He and his paramour, Josie Mansfield, would stand at the gangplank welcoming passengers aboard. All of this buffoonish behavior seemed to amuse New York society, which only encouraged Fish into great acts of questionable taste. In 1867 he took hold of the old Fall River line, and the Bristol and the Providence became part of its fleet. The oldfashioned placement of the boiler on the guards was ignored, and the boilers were placed inside the hull. Rather than the usual fan pattern, the paddle-box fronts were rendered in what might be described as the Capitol Dome pattern. The Bristol burned at the Newport dock on December 30, 1888, just after completing a trip. The Providence was retired about two years later but was kept in reserve until around 1896.

Not long after the Bristol entered service, the Norwich line introduced the City of Lawrence, which boasted an iron hull. A few of the lines had talked about such improvements, but it was not until 1881 that the New London line put the iron-hulled City of Worcester in service. She had electric lighting, which was an innovation in steamboating. In 1898 she sank at Cormorant Reef, Rhode Island, but only went down to her upper decks. The boat was raised and remained running until 1915.

9.5. The main cabin of the Bristol is shown in this engraving to be as grand as any palace hotel in the world.

(Jim Harter collection)

In May 1877 steamer service to Providence was revived by a new line. One of its new boats, the Massachusetts, had two hundred rooms and several family-size compartments. The dining room was on the main deck rather than below as was customary. Aft of the dining room were staterooms and berths set aside exclusively for ladies. Almost an hour before departure, an orchestra would begin playing in the main saloon and continue to do so as the boat began its trip. Most of the sound lines had docks on the Hudson River, along West Street. The Massachusetts left from Pier 29 and headed south to the Battery and Castle Garden, where she passed around the southern tip of Manhattan. She would then bend to the north and pass the great line of large sailing ships along South Street. There were wharves on both sides of the East River crowded with ships. The boat would pass Brooklyn and the navy yard, continuing on a northern course past the shipyards at Greenpoint. All the while legions of boats would pass by as ferries darted back and forth in front of and behind the Massachusetts.

The boat would then steam alongside the long, slender Blackwell's Island, square in the middle of the upper East River, moving slowly because of the traffic of ships. It would then turn eastward and thread its way through the narrow Hell Gate, past Ward's Island and Randall's Island, until it entered the sound. It would pass Riker's Island, Flushing Bay, and enter a narrow channel at Throgg's Neck. Down below, the orchestra would temporarily stop playing when dinner was served. Some passengers chose to sup later and stay on deck to catch a few more sights of the boat's entrance into Long Island Sound proper. To the right was King's Point, and up ahead, Pelham Bay. As the Massachusetts moved along, the towns grew smaller, especially on Long Island. There were cottage villages, green fields, rocky bluffs, and an occasional lighthouse. Passengers would go below to be in time for the last leavings of a beautiful meal. The musicians reassembled at 8:00 PM and offered two more hours of beautiful melodies. Then passengers would go to bed, to rest awhile, before an early morning landing. In Providence, passengers boarded a boat train that would reach Boston in one hour and fifteen minutes. Holiday passengers could go on by rail to Cape Cod, or the White Mountains, or as far north as Bar Harbor for the summer.

Later in the nineteenth century the service varied by the season. Most of the sound lines carried seventy to seventy-five passengers a day, even in the winter months. However, during the summer peak each boat might carry up to a thousand. The Fall River line, for example, ran its smaller boats in the winter and offered a fare reduction of 25 percent. During the warm weather months they ran four boats a day. The basic fare was $4, with an extra charge of $1-$2 for a stateroom, depending on its size.

There was much to praise about the sound boats. They were large, comfortable, reasonably fast, and safe. The crews were helpful. The officers were gentlemen and as polite and refined sailors as are likely to be found. A popular writer of the day, J. D. McCabe, was offended by the number of ladies of ill fame who made the boats their home and plied their infamous trade in the most shameless manner. He said that a trip on these deluxe boats was an experience never to be forgotten. Perhaps that was true because of the ladies he so disparaged, but the average passenger was more likely bothered by the difficulty encountered in getting on and off the boat at the dock.

Runners were hired to persuade travelers to ride on “their” boat and to avoid the inferior vessel operated by competing lines. These impertinent and aggressive salesmen were paid a fee for every passenger they could deliver to the ticket booth. They would block passengers from buying a ticket while degrading the vessel nearby, saying she was unsafe and had a hole in her bilge large enough to crawl through, the captain was a drunk, the boilers blew up regularly, the food was like fodder, or she would get stuck on a sandbar every trip for three hours. At the same time, two or three other hucksters shouted the merits of their particular vessel and the defects of the competitors. They held on to your coat or tried to grab your bag and move you away from the dock to one down the street. Each of them offered a cheaper fare or a free meal if you would only sail on their boat. A strong traveler would pull away from these rascals but not with ease. Otherwise, one could only hope a policeman would appear to handle the situation.

Getting off a boat could be as great an ordeal, because passengers leaving the vessel faced a gauntlet of cab drivers, porters, and expressmen, all seeking their business. They shouted, yelled, and grabbed in a wild and aggressive manner. The hackmen wanted your taxi fare, while the porters and expressmen wanted your baggage. In the Victorian era, upper-class travelers needed many changes of clothes in that dressed-up age when appearances were important. This called for a large wardrobe and hence many bags and trunks. A New York Times reporter recorded a scene at the Fall River dock late in August 1882. It looked and sounded like a mini riot, he said, and the three policemen assigned to keep order were overwhelmed. They did what they could to keep a path open for the passengers. The weak and timid were literally grabbed by a burley cab driver and pulled over to his vehicle and pushed inside. The young, fleet, and strong might escape, but they faced a second lineup of hackmen and porters on West Street, where the hectoring began all over. A certain number of older gents with a military bearing, head held high, would hold out their walking stick as if to say, “Get out of my face or get a taste of this stick.” They alone might be allowed to pass through unmolested.

Despite the building of more railroads, New Englanders seemed determined to go by boat when traveling to Manhattan. It was fashionable and more dignified and it became a tradition. Grandfather had always taken the boat train to Fall River and continued on by steamer to Gotham. His son would do the same, and the grandson, not one to upset the status quo, would do likewise. They knew the schedule by heart. The boat train left Park Square station at 6:00 PM and arrived at the Fall River wharf at 7:25. The steamer left just ten minutes later and arrived at Pier 28 in New York City at 7:30 the next morning.

Maintaining the loyalty of its traditional patrons prompted the Fall River management to purchase a series of new vessels starting in 1883. The Pilgrim was the first of this iron hull generation. It was a double hull with 90 watertight compartments and 6 watertight bulkheads that extended to the top of the hull. She was 385 feet long and had 219 staterooms and 10 parlor bedrooms. There were 695 berths on board, including 93 for compartments. The Pilgrim would carry 540 passengers and 200 crew members. The interior of the boat was similar to earlier steamers such as the Bristol. There was no effort to update this aspect of the vessel design. Figure 9.6 shows the Pilgrim as she appeared when first entering service in June 1883. The Puritan followed in 1889 and was somewhat longer than her predecessor. The hull was steel in place of iron. She carried 800 passengers and had a compound engine for greater fuel economy.

9.6. The Pilgrim became the flagship of the Fall River line when she entered service in 1883. The several interior views show the attention to passenger comfort, including electric lighting.

(Leslie's Weekly, June 30, 1883)

But the Puritan was to have a different and more sophisticated look about her. She was in no way modest or puritanical in dress. Traditional steamboat interiors were fabricated and designed by ship carpenters whose idea of beauty was anything that could be cut with a scroll saw. The Puritan was to be artistic as well as seaworthy. The interior followed the Italian Renaissance plan for ornamentation. Care was taken that the gilding was not too heavy. Dark varnished woods and bright accent colors were less often used. Boston native Frank Hill Smith (1842–1904) directed the work. He had been educated in France, specializing in interior decorating, and favored classical designs. Smith and his artists used white or pale colors and decorations molded in low relief. Walls were divided into panels by fluted pilasters. Dignified figures – often half-draped females – filled in the panels. The ornamental ironwork was graceful and not gilded. The hardware was ornamental but cast in dark bronze (figs. 9.7 and 9.8). Other boats in the Fall River's new fleet were the Plymouth, Priscilla, Providence, and the mighty Commonwealth of 1908, all of which proved to be excellent boats.

Train service improved between Boston and New York after the opening of the New Haven shoreline in 1889. Completion of the Hell Gate Bridge in 1917 brought the New Haven trains directly into Pennsylvania Station. This was the beginning of direct passenger service from downtown Boston into the heart of Manhattan. But no matter, the old ways continued to a degree and conservative Yankees preferred the sound steamers. Passenger service on the Fall River line actually peaked in 1906 at 444,500 and stayed near that number during much of the 1920s. However, by 1928 the line was losing money. The Depression cut patronage so that by 1936 traffic was down to about 127,000. Yet the Fall River line took pride in its good safety record, which recorded only one passenger fatality in its history. This meant little to workers, who wanted a wage increase in the summer of 1937. The line's management reacted to the workers’ demands by ending operations. A judge granted the Fall River line permission to shut down on July 27, 1937. And so ended the strike and a glamorous chapter in coastal steamer history.

9.7. The Puritan entered sound service in 1889. She was a giant at 420 feet. Her paddle wheels weighed 100 tons. She was also beautiful as can be seen by this engraving of her grand staircase.

(Century Magazine, July 1889)

NEW ENGLAND COASTAL TRAVEL

New England has always been associated with the sea. Most of its population continues to live along the Atlantic Coast. This section of the nation was devoted to shipbuilding, fishing, the China trade, and seafaring in general. Today the area's most fashionable seaside summer resorts are at Bar Harbor, Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket. Yachting is more than a pastime for those Yankees who love the sea and wind.

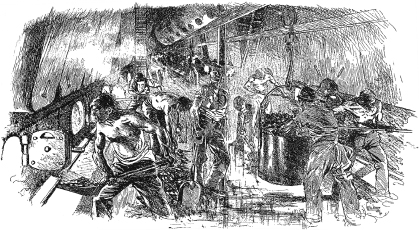

9.8. A squadron of stokers shoveled vigorously to feed her furnaces to produce enough steam to drive the Puritan along at 20-plus mph.

(Century Magazine, July 1889)

Colonial New England was a maritime economy. Many worked their farms during the spring and summer but cut timber or built ships during the other seasons. Some fished or converted logs into boards. Large tracts of virgin timber furnished excellent lumber for ship hulls, masts, and spars. The tall trees found in Maine were ready-made for masts. The plentiful supply of wood reduced American shipbuilding costs, compared to European yards, by 60 percent, and America built many vessels for the British merchant fleet. Large vessels were being built at Salem, Massachusetts, as early as 1641. The schooner was introduced by Yankee shipwrights in 1716 and grew in popularity over the next century because it required such a small crew to handle the sails. Schooners grew in size and remained economic into the twentieth century.

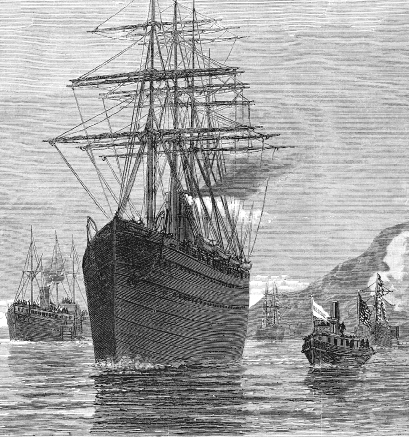

New England's reputation for fine sailing ships was greatly enhanced by the clipper ships built by Donald McKay (1810–1880) at his East Boston boatyard. McKay was a native of Nova Scotia but came to New York as a teenager to become an apprentice ship's carpenter. After mastering the trade he opened his own yard near Boston in 1845. The Stag Hound was his first clipper, completed in 1850. She was long and narrow and intended for speed rather than maximum cargoes. Such ships were described as “knives with sails.” The plentiful sails towered almost 200 feet above the deck. It was McKay's hope that a line of such fast vessels might capture the cotton trade between New Orleans, Savannah, and Boston; however, this scheme did not succeed. At the same time, British builders introduced composite hulls with iron frames and wooden planking, which produced a stronger and cheaper vessel than the American all-wooden hulls. The panic of 1857 forced McKay to close his yard. He attempted iron ships but failed to make a profit and so retired in 1869.

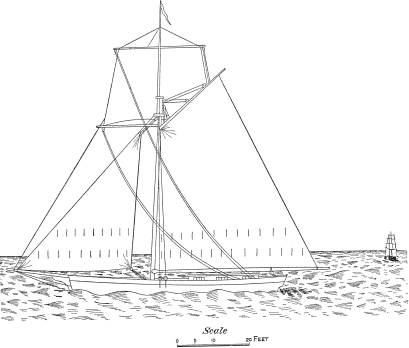

9.9. Sloops were popular along the Atlantic Coast from New England to Florida. They carried passengers and freight between small ports. This vessel was about 60 feet long and featured a topsail.

(1880 U.S. Census, Vol. 8)

Clipper ships sold for about $90,000 and routinely set speed records that exceeded those of steamers of the period. A clipper named the Northern Light dashed from San Francisco to Boston in just seventy-six days and six hours. By 1883 there were 270 clippers in service. The great American historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote this eloquent description of a proud clipper ship's entry into Boston Harbor during the age of sail.

After the long voyage she is in the pink of condition. Paintwork is spotless, decks holystoned cream white, shrouds freshly tarred, ratlines square. Viewed through a powerful glass, her seizings, flemish-eyes, splices, and pointings are the perfection of the old-time art of rigging. The chafing-gear line has just been removed, leaving spars and shrouds immaculate. The boys touched up her skysail poles with white paint, as she crossed the Bay. Boom-ending her studdingsails and hauling a few points on the wind to shoot the Narrows, between Georges and Gallups and Lovells Islands, she pays off again through President Road, and comes booming up the stream, a sight so beautiful that even the lounging soldiers at the Castle, persistent baiters of passing crews, are dumb with wonder and admiration.

The coastal trade began with the earliest settlers around the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The only convenient way to travel between Plymouth and Boston was by boat. Small sloops and ketches were soon venturing along the coast (fig. 9.9). These small boats had only a single mast, and there were no cabins and few comforts or protections from the weather. They could move quickly with a good breeze, but at the first sign of a storm these little craft would seek a safe harbor. Boats that didn't head to shore soon enough would be blown out to sea. Fishermen were the most subject to such misadventures and were blown out to the Grand Banks off of Newfoundland. One New England crew found itself far to the south after a gale blew them east of Bermuda. What happened to fishing boats happened to the largest sailing vessels as well.

A lively trade developed between ports along the Atlantic seaboard. Coastal ships carried lumber, stone, fish, and lime to the south. Bangor, Maine, became the lumber capital of New England after 1820. During its peak year of 1872 it shipped out more than 240 million board feet. Excellent granite was found on the mainland, as well as on some of the islands off the northeastern coast, and would be carried south to Boston, Philadelphia, and other ports by ship. Some blocks weighed as much as 650 tons. Firewood went from Maine to Boston by coasters. These same vessels would carry coal back east. Perhaps the most remarkable fact about the Yankee seaman was the beginning of trade with the West Indies in about 1640. A schooner could expect to reach Philadelphia from Portland, Maine (about 450 miles), in about five days with favorable winds. It could require almost three times longer if the winds were contrary.

One of the most important changes that occurred to coastal shipping before the advent of steam power was the establishment of ship lines that worked on common carriers. Traditionally the ship's captain carried his own goods or that of his partners. He sailed when and where he pleased. The ship lines ran on a fixed schedule over a fixed route. For example, the Red line sent out a ship between New York and Charleston every Wednesday. This vessel was open to all shippers at a uniform charge. Many small shipments put together added up to a full or nearly full load. The idea became so popular that by 1815 there were boat lines between every major port on the East Coast. Some lines even serviced Richmond, Virginia, by using smaller vessels to navigate the James River.

The steamboat appeared in northern waters about a decade after Fulton convinced American travelers that such vessels were both safe and convenient. A small open boat named the Tom Thumb was built in Boston in 1818. It was only 30 feet long and had paddle wheels. Initially it was used on the Kennebec River between Bath and Augusta. Despite its small size, it was used along the Maine coast and ran as far east as Rockland. A larger boat appeared in 1824 intended for service between Portland and Boston. It was built in New York and was named the Patent. The vessel was 80 feet long and had a proper cabin for passengers, plus a separate ladies’ cabin. Finished at a cost of $20,000, it exceeded the humble Tom Thumb in every particular. It operated at 10 knots. The fare was $5, meals included. The Patent ran on its intended route for six years and then was transferred to the Penobscot River for another five years. After that assignment was concluded, she was sold down south. Another interesting pioneer was the Eagle, which was set to work between Boston and Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1818. This route, just 11 miles long, cut across Boston Bay and offered local citizens a quick way to commute. By 1832 the route was taken over by the Boston-Hingham Steam Boat Company. Half a century later this line became part of the Nantucket Beach Steam Boat Company. It was more into the excursion trade than commuter business and was especially busy in the summer season.

In 1835 Cornelius Vanderbilt tried to take over the Boston-to-Portland route. Why Vanderbilt desired such a line is unclear, because the traffic between the cities was not sufficient to generate a large profit. Boston was a major city, true enough, but Portland at the time had only about thirteen thousand residents. Although Vanderbilt normally employed the very best vessels, he now proceeded in an uncharacteristic manner by entering two well-used vessels to win the competition for the route. The Chancellor Livingston of 1816 was the last boat designed by Robert Fulton. When new it was possibly the best steamboat afloat. She was designed for Hudson River service but operated successfully on Long Island Sound. She had been re-engined in recent years but even so remained an obsolete boat. Her companion was another Fulton boat, which had been built for Russia but never delivered and was subsequently renamed the Connecticut. She was smaller than the Livingston but was completed in the same year. The established line he had hoped to defeat held fast, and Vanderbilt was forced to retire. He returned, however, in 1838, hoping to unseat the local operators on the Boston-to-Portland route. Fares were cut to $1, and Vanderbilt had a fine boat to represent him this time. But the local vessel outran Vanderbilt's best and made the run to Boston in a record nine hours and ten minutes. The commodore did not accept defeat easily, but in this case he decided to give New England a long rest.

The Boston and Bangor Steamship Company was established in 1833 by a group of Boston investors. A new boat named the Bangor was built in New York for the company. It burned twenty-five cords of wood on each trip. In 1842 the vessel was sent to Turkey for service on the Mediterranean Sea. There was a second Bangor built for the Boston-to-Bangor service by Betts, Harlan, and Hollingsworth of Wilmington, Delaware. This was an iron-hull vessel driven by screw propellers and was very advanced for its time when completed in August 1845. On her second trip a fire broke out in the boiler room. It was decided to run the Bangor ashore near Castine, Maine. Passengers and crew were taken off without any injuries, but the boat was seriously damaged. She was rebuilt and returned to service. Late in 1846 the Bangor was sold to the U.S. Navy and refitted as a gunboat for service in the Mexican War.

A more typical steamer for the time also served the Bangor route. This was the Penobscot, built by James Cunningham of New York in 1844. She had a wooden hull, side wheels, and a walking beam engine. Samuel Stanton produced an attractive ink drawing of this vessel. The Penobscot was renamed the Norfolk and sent south where she was lost off the coast of Delaware on September 12, 1857, in the same storm that sank the Central America. This boat gained considerable notoriety in more recent years when its cargo of gold was recovered from the frigid depths of the Atlantic Ocean.

Miss Isabella Bird, mentioned earlier, was an English lady who toured Canada and the United States in the early 1850s and published a book about her travels in 1856. After landing in Halifax and touring Nova Scotia, she departed from St. John, New Brunswick, for Portland, Maine. It was a bright day in August when she stepped aboard the Ornevorg, a former Long Island Sound side-wheeler now being used in this short international run. Miss Bird entered through a side door on a lower deck into what looked like a large hall. It had a ticket office and a curtain that separated the ladies’ compartment. Behind the curtain she found sofas, rocking chairs, and tables. This otherwise comfortable space was too airy for Miss Bird. Berths were built in on both sides of the room. The drapes were satin damask while the curtains were of muslin with rose-colored binding. On the deck above was a large saloon for the male passengers, with 170 berths. The large beam engine propelled the boat along at 15 mph. A stop was made at Eastport, Maine, where the midday meal was served, because dining was much more pleasant when the boat was stationary. The ladies were seated first, but the men made a rush for the food when they were brought in. There was an abundance of food for everyone. The table was piled high with pork roasts, leg of mutton, broiled chicken, turkey, roast duck, beef steaks, yams, tomatoes, squash, and endless breads and pastries. While Miss Bird was finishing her soup, the others were eating their dessert. A waiter asked her for a dinner ticket or 50 cents.

The sea began to pick up with a fresh breeze. The boat was too low in the water and had so little free board that water came rushing into the passenger deck. A wave came down the companionway into the ladies’ compartment and upset the tea table, scattering its contents around the deck. The boat was now rocking, groaning, and straining heavily as a gale blew in. A lamp fell from the ceiling, rendering the cabin dark. Furniture continued to be knocked around, and enough water was in the lower decks to put out the fire under the boilers. The boat was now at the mercy of the sea. The men pumped and bailed. Miss Bird was thrown against a bulkhead and was stunned insensible for three hours. By morning the storm began to moderate. Another boat pulled alongside and gave the stricken vessel a tow into Portland, arriving at 1:00 PM, damaged but afloat. The passengers were simply happy to still be alive.

Many towns along the New England coast did not have harbors or docks for larger boats. Some of these vessels would stop as close to such towns as they could, and small boats could shuttle back and forth with passengers and cargo. It was an inexpensive, if not notably efficient, way for a hamlet to have access to good transportation. In other areas, local lines would use small boats that could land in shallow harbors. There were some steamboat operations that specialized in local service. Cosco Bay lies offshore from Portland and is dotted with islands. The Cosco Bay Steam Boat Company offered service to these islands with four miniature side-wheelers. It was claimed there were 365 islands in the bay. Daily mail service was offered, and the boats were especially busy during the summer resort season. The Harpswell Steam Boat Company, also based in Portland, was another “island hopper.” The Portland Packet Company took vacationers directly from Boston to Bar Harbor, a rich man's summer haven after it was discovered by the Rockefellers. In the early 1890s boats left Boston's India Wharf every evening at 7:00 except Sundays. After Mount Desert Island was partially converted into a national park, more ordinary tourists began to visit Bar Harbor.

Steamboating was not damaged by the spread of railroads in coastal New England, as the boats managed to compete fairly well. It was the automobile that destroyed passenger service by both rail and sea. While the automobile was the rich man's toy, an ambitious businessman named Charles W. Morse attempted to consolidate the northeastern coastal lines as far north as the Canadian Maritimes. In 1901 he created the Eastern Steamship Company. Several lines were combined, some of them very old, such as the Boston and Bangor and the International Steamship Company. Morse had previously made a fortune in the ice business and other enterprises. He controlled a number of banks that proved useful in financing his steamboat adventure. He was counting on the good economic times continuing but did not foresee the panic of 1907. Morse was ruined and lost control of the Eastern Steamship Company, which was forced into receivership. It recovered and continued to do well until 1914, when it once again failed. However, this was only a temporary setback, and good times were ahead. In 1916 the Cape Cod Canal opened, which offered a direct water route to Boston. The Eastern Steamship Company purchased the Boston-to-Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, ferry line. This service started in 1855 and proved successful because it was more direct than the overland routes. Service continues today, but it now runs from Portland to Yarmouth. Two new boats were built in 1924 for the Eastern Steamship Company, and traffic remained strong, especially in the vacation trade, until 1930. The effects of the Great Depression meant an end to many businesses, and the Eastern Steamship Company was no exception. The lines from Boston to Portland closed in 1932, and the Bangor service was gone three years later. The New-York-to-Boston boat ran as late as 1941. The Yarmouth line was closed during World War II. It was restored after the war but ran only until 1954, when the Canadian government took over the operations as a public service.

SOUTHERN COASTAL TRAVEL

Most modern Americans go south in the winter to find sunshine, warm beaches, and orange blossoms. In the antebellum era southerners headed north in summer to escape the heat and tropical diseases of Dixieland. The most comfortable place for southerners was Newport, Rhode Island. Here was a seaside town in the heart of New England that contained almost no abolitionists. It started as a seaport and working place for traders, fishermen, and shipbuilders. It had no ambition to be a fancy resort catering to wealthy southerners, but that is how it evolved by about 1730. Prosperous sea captains built handsome homes and patronized excellent schools. Art and music flourished to a degree, and all of this superficial refinement appealed to the upper-class southerners. The wealth of Newport was built on the rum and slave trade. Ships carrying rum distilled in Newport sailed to the west coast of Africa and traded rum for slaves. The slaves were brought back to the West Indies and traded for molasses that was carried north to Newport, where it was converted into rum or sugar. This exchange was one of the most lucrative trades for American seamen. Ships had full cargoes on all three legs of the triangular trade and profited each mile of the way. The final section of the voyage followed the eastern U.S. coast from Florida to Rhode Island. Because almost everyone in Newport was supported by the slave trade to some degree, abolitionist sentiments were subdued at best. Southerners might go there with their house servants and never have to be confronted with the issue of slavery. Newport became such a popular resort for the Old South, many referred to it as the Carolina Hospital. Boats heading north from late spring to early fall were well patronized.

During the American Revolution the British occupied Newport, putting an end to its glory days as a seaport. It fell into a general decline after the war but retained its resort trade. By the 1840s rich northerners were beginning to assemble there as an escape from the overheated cities of the northeast. Anthony Trollope reported it as still busy in September during his visit in the early 1860s. Southerners were no longer present at this time because of the war. Wealthy New Yorkers made it a summer retreat for the top four hundred in the American society. Great mansions, called cottages, were built by the Astors and the Vanderbilts. But high society is fickle, and by 1920 the magic of Newport had worn off and the four hundred withdrew to newer and more fashionable locations. Today tourists come to see what remains of the great houses and wonder how this sleepy place could have once been the largest seaport in colonial America.

Southern merchants also headed north in the summer on yearly buying trips to restock their shelves with bonnets, shoes, perfumes, and other fancy goods best found in New York City. Some was of local manufacture, but much was imported from England, France, and other overseas suppliers. The businessmen were also happy to have a good excuse to leave the heat behind them, and some would linger on until September. The best way to reach Manhattan was by packet boat, the same vessels that carried so much cotton northbound. These same vessels returned to the south laden with fancy goods that were high-value cargoes. When the sailing packet Louisa Matilda wrecked just north of Hatteras, North Carolina, in August 1827, her cargo's estimated value was between $300,000 and $400,000. New York was a fine place to find entertainment and diversion. In 1825 it was estimated that ten thousand southerners sailed from various southern ports to New York City. No breakdown was included to distinguish just how many of this total were merchants or vacationers.

Sail prevailed longer on the southern routes than it did along the northern coastline. Steam was championed by New York-based coastal lines, but it took longer to take hold. One of the first steamers to head south was the Robert Fulton, launched at New York in 1819. In April of the next year it ran to Cuba, some 1,300 miles, in seven days. Part of the trip was made through a storm, and the Fulton proved seaworthy. The boat ran successfully on this route for five years but could not maintain a regular schedule as a single vessel. Profits were not enough to justify a second boat, so the service was suspended.

Robert Albion, in his seminal study of square riggers, contends that marine historians have generally ignored coastal history in favor of more glamorous deepwater trans-ocean subjects. He contends that American coastal routes were universally long and were as great a challenge as crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Good ships and skillful crews were needed to get coastal cargoes and passengers to their destinations. Expert seamanship was required as well, of course, in order to average 100 miles a day whether the sailing ship was on the edge or at the center of the sea. At this speed, Charleston was 6.6 days from New York, Mobile was 17.7 days, and New Orleans was 18 days. Adverse weather and contrary winds could adversely affect sailing schedules. One of the slowest trips between New York and Charleston took 23 days. Being blown off course or out to sea made timely travel by sea impossible. Pirates were active in the Gulf of Mexico into the 1830s, not only interrupting schedules but sometimes murdering or torturing ship crews. Those merchantmen carrying specie shipments were generally well armed.

9.10. The Home (1838) was a pioneer in the New-York-to-Charleston trade. She sank on her third trip to the south at Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

(S.A. Howland, Steamboat Disasters, 1846.)

Perhaps the most important fact concerning southern coastal trade was its control by New York shipping interests. These shrewd and aggressive agents controlled the cotton trade by about 1835. This meant cotton sold to New England and British mills went via New York. It involved hundreds of thousands of bales a year and thus amounted to huge transportation fees. Southern cotton growers contended that for every dollar received for their crop, 40 cents went to New York. Charles Morgan was among the largest of the New York shippers to benefit from the southern coastal trade.

Charles Morgan (1795–1878) came to New York City in 1809 to make his fortune. Over the next several decades he did so, mainly in southern shipping and railroads. In 1819 he invested in a sailing packet working the New York, Charleston, New Orleans trade. He later joined James Allaire, a marine engine builder, in starting a steam packet line to service the same ports. The two men began with a line to Charleston in 1832. Four years later service was extended to Havana, Key West, and New Orleans. In 1837 Morgan pushed the operations to Galveston, Texas. This was the pioneer southern steam packet operation, but it was a troubled business. Several boats were lost and passengers lost confidence in it.

The sinking of the line's Home was featured in a sensational book of the time by S. A. Howland called Steamboat Disasters and Railroad Accidents in the United States. The boat owned by Morgan and Allaire had made a fast trip to Charleston, South Carolina, in just sixty-four hours. Good publicity helped sell tickets, but the next voyage, on October 7, 1838, was to be her last. It started poorly when the Home became stuck on a shoal before leaving New York Harbor. A rising tide set her free after a few hours, but once into the Atlantic Ocean the Home was overwhelmed by a stubborn gale. As they headed south the boilers failed, the hull began to leak, and the sails, now the only means of power, were torn to pieces. She made it as far south as Cape Hatteras when the captain decided to drive the vessel onto the beach and end the trip before she came apart at sea. It was a desperate measure, and the boat came to pieces in the surf before landfall. Ninety-five lives were lost near the beach at Ocracoke, North Carolina. Forty people managed to reach shore, but many children and women were among those lost (fig. 9.10). The unfavorable publicity from this tragedy prompted Morgan and Allaire to abandon their operation. But Morgan was only temporarily stalled in his effort to build a coastal shipping business.

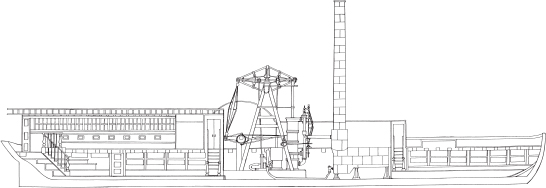

9.11. The North Carolina ran between Wilmington, North Carolina, and Charleston, South Carolina, in the years 1838 through 1840. It was built in New York City.

(Thomas Tredgold, The Steam Engine, 1838)

Morgan refocused on his operations in Texas, and before others reorganized the business opportunities in this remote part of Mexico, Morgan monopolized the Texas trade. He built a railroad east from Texas that ended opposite New Orleans on the Mississippi River. After Texas became a republic and then a state, Morgan's transport empire flourished. After his death, the Southern Pacific Railroad took over his transport business that stretched from New York to Texas.

The internal plan of a cotton state coastal steamer, the North Carolina, was printed in Thomas Tredgold's folio volume The Steam Engine (fig. 9.11). It was constructed in 1838 for a coastal line serving Wilmington, North Carolina, and Charleston, South Carolina. Wilmington was 30 miles up the Fear River; the remaining 130 miles to Charleston was along the Atlantic Coast. The North Carolina was almost 160 feet long with a beam of 24 feet. She had side wheels and a single-cylinder low-pressure engine 40 inches in diameter with a 10-foot stroke. The engine was rated at 100 hp. Copper boilers were used because they were more durable than iron ones, since seawater was used to make the steam. Two cabins had beds for 72 passengers, and another 28 temporary beds could be set up in the main cabin. The coastal line had four boats, three built in New York, under the direction of Cornelius Vanderbilt, and a fourth made by Watchman and Bratt of Baltimore. Operations were done at night, so the vessel ran slowly as a precaution. The journey took 14 hours at an average speed of 11 mph. Fourteen cords of wood were consumed during each trip. Passenger loads averaged only 18 per trip, and some of the travelers rode only partway, resulting in a rather disappointing gross income of $1 per rider. Operating expenses, wages, fuel, repairs, and so forth came to a little over $30,000 for a nine-month season. It was hoped that revenues would rise as the rivers became better established. However, there was more trouble ahead for this small coastal line. Late in July 1840 the North Carolina was struck by the steamer Governor Dudley. They were at sea about 20 to 30 miles northeast of Georgetown, South Carolina. The accident happened at about 1:00 AM, and both captains had just gone to bed. The North Carolina sank almost immediately, yet no lives were lost. Most of the luggage was lost, however, and because some of the passengers were congressmen returning home, a great deal of money was lost as well.

Meanwhile, on the eastern seacoast, the age of sail continued south of Philadelphia. Large ports such as Savannah were served by six packet lines consisting of thirty-eight barks and brigs (fig. 9.12). They sailed alternate days to divide up the business. Finally in 1846 the U.S. Post Office awarded mail contracts that were large enough to encourage a new steamboat line between New York and Charleston. A fine new steamer named the Southerner made its first trip to Charleston in September 1846 and completed the journey in two days and eleven hours. Other mail contracts encouraged steamer lines from New York to Key West and Havana.

The most convenient place to see U.S. coastal trade in action was New York Harbor. Boats lined up in close ranks along the Hudson and East River docks. Boats left daily for dozens of ports along the East Coast and the Caribbean Islands. One of the biggest coastal lines in the 1890s was the Clyde Steamship Company located at Pier 29 on the East River at the foot of Roosevelt Street. It was easy to find, because the pier was below the Brooklyn Bridge. This company was founded in the 1840s by Thomas Clyde, who immigrated to Chester, Pennsylvania, from Scotland in 1820. Clyde worked with John Ericson in perfecting the screw propeller. In 1844 he built a vessel named the John S. McKim, said to be the first screw propeller used in the coastal trade. The McKim ran between New York and Charleston.

Over the following years the Clyde line expanded its operations to include Boston; Philadelphia; Washington; Norfolk, Virginia; New Berne, North Carolina; Georgetown, South Carolina; and Jacksonville, Florida. Its boats ran up the St. John's River in Florida for 195 miles, landing at Green Cove Springs, Palatka, Astor, Blue Springs, and other Florida landings. A subsidiary line to the West Indies left from Pier 15 of the East River for Turk's Island, Haiti; Puerto Plata, in the Dominican Republic; and Samna, Sanchez, and San Domingo City, in the Republic of San Domingo. Thomas Clyde's son William played an active part in the steamboat business. In 1873 he became president of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. He managed the Panama Railroad and for a time the Richmond and Danville Railroad as well.

9.12. Brigs were well suited to coastal service and were a common type of sailing vessel in that trade before the advent of steamships.

(Merchant Vessels of the United States, 1892)

The Savannah line operated by the Ocean Steamship Company was acquired by the South Carolina Railroad in 1872 (fig. 9.13). This line served both Boston and New York and thus did much to strengthen the Port of Savannah. In 1890 it ran four boats a week from Pier 35 on the Hudson River. Time to Savannah was fifty-five hours, and the cabin fare was $20. Vacationers took the Savannah line to Bermuda for a quiet rest; it was only two days from New York. Visitors found a restful beach warmed by the Gulf Stream. It was a balmy and relaxing place to visit, and it had a fine hotel. William Dean Howells, Mark Twain, and Woodrow Wilson were all guests at the Princess Hotel.

The Old Dominion Steamship Company ran boats from Pier 26 on the Hudson River four times a week to Norfolk and Newport News, Virginia, in just twenty-four hours. The fare was $8 and included all meals. Old Point Comfort offered a resort hotel. The Cromwell line was established in 1855 by H. B. Cromwell and Company. By 1860 it had ten screw propeller steamers running to Charleston and Savannah. It was building more boats to connect Boston and Charleston. By 1890 it offered service every Wednesday and Saturday from Pier 9 directly to New Orleans. A special vacation cruise of sixteen days with a four-day layover in the Big Easy was offered for $60. The New York Times carried a story about the southern coastal trade out of the Port of New York in January 18, 1860. The business was flourishing, according to this report, and went far beyond passenger travel. The Harden Express line had been in southern trade for eight years and never experienced such a good business with large and small shipments. The Adams Express Company reported handling sixteen hundred packages for the south during the week before Christmas.

9.13. The Savannah line was a railroad-operated steamship company that continued running into the 1940s.

(Official Guide of the Railway, 1893)

The Ward line started running between New York and Cuba in 1840 with a small fleet of schooners. James O. Ward, formerly of Roxbury, Massachusetts, started the operation and passed it on to his son, James E. Ward, in about 1856. The younger Ward soon had schooners landing in many West Indies ports. The New York and Cuba Mail Steamship Company, as the company was also called, acquired its first steamer in 1866. By 1877 it had faster steamers, which made the trip to Havana in four days and one hour. The return trip was faster yet, three days and nine hours, because of the Gulf Stream. By 1892 the Ward line had ten steamers servicing Cuba, Mexico, and Nassau.

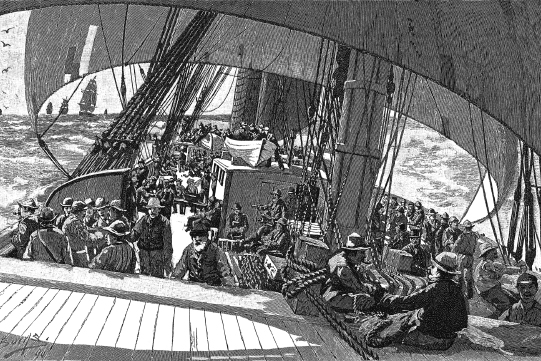

9.14. Passengers enjoy a concert on the rear deck of this small steamer heading for Coney Island on the Atlantic Coast just outside of New York Harbor.

(Harper's Weekly, August 6, 1881)

Although most citizens could only dream of taking a steamer to the Caribbean Islands or the ports of old Spanish Main, even the poorest New Yorker could have a small sample of coastal sea travel for just 25 cents. This modest fare purchased a round trip to and from Coney Island. The 12-mile excursion started at Pier One at the Battery or southern tip of Manhattan Island and headed down the upper bay past the Statue of Liberty and out to sea at Sandy Hook. Here the boat entered into the lower bay of New York Harbor. The steamer then turned north and continued along the eastern coast of Long Island to Coney Island (fig. 9.14). Some trips continued north to Manhattan or Rockaway Beach. With a round trip lasting about two hours, the passenger was at sea and gained brief exposure to coastal travel. Some passengers stayed aboard just to enjoy the sights of the busy maritime scene, the sun and fresh air, and some time away from the congested city. Excursion boats had started service to Coney Island in about 1845, but the trade was taken over by the Iron Boat Company, which built seven new steamers in the early 1880s. This firm adopted the motto “cannot burn, cannot sink” to assure timid travelers about the Iron Boat line's safety. But accidents do happen. In July 1894 two of the line's boats collided, and a third, the Pegasus, hit a cattle boat one day later. With three boats out of service at peak season, the Iron Boat line had difficulty handling its traffic of ten thousand passengers a day or in providing a boat every thirty minutes. These delightful, if abbreviated, sea excursions continued until about 1932.

New York was the dominant eastern coastal port and so prevailed over the Atlantic coastal trade. There were competitors elsewhere attempting to break the Empire City's monopoly, such as the Merchant and Miners Transportation Company of Baltimore. The firm was incorporated in April 1852 but was slow in getting under way. Service started in December 1854 with a seventy-six-hour trip between Baltimore and Boston with a big side-wheeler named the Joseph Whitney. When two more boats were acquired in 1859, service was expanded to Savannah and Providence. Two years later the Civil War created an emergency and the line's boats were seized by the federal government, but by 1864 the line was able to resume operations on a limited basis, and three years later they could offer service to Boston and Norfolk. In 1873 the line to Providence was restored. A Savannah line was purchased in 1876, allowing the company to resume its southern connection. By 1890 Merchants and Miners had eleven steamers, all with iron or steel hulls. In 1907 the line was taken over by the New Haven Railroad, but this arrangement was terminated seven years later because of the railroad's financial problems. During World War I the federal government took over the fleet as part of the war emergency. By 1921 Merchant and Miners had recovered and went on to rebuild its fleet to eighteen vessels. The Great Depression created another test for all transportation companies. The Merchant and Miners line was again taken over by federal action early in 1942 for the duration of World War II. Private ownership was not restored until 1948, but the shareholders decided to dissolve the corporation rather than resume operations, thus ending Baltimore's coastal shipping line.

Southern coastal lines were controlled largely by northern businessmen. One of the more dominant of these was Henry B. Plant (1819–1899), a Connecticut Yankee who spent most of his adult life in the south. He had declined the offer of a college education and went to work at the age of eighteen as a deckhand with the New Haven Steamboat Company. He soon found work with the Adams Express Company. In 1854 he was sent to Augusta, Georgia, to manage the company's business in the southern states. A few years after the Civil War began, Plant reorganized the business as the Southern Express Company and worked to cultivate good relations with Confederate leaders. But he felt compelled to leave the south in 1863 because he felt so unwelcome. He returned after the war and revived the express business. By the late 1870s he saw better opportunities in the railroad business and purchased the Atlantic and Gulf Railroad. As he added new railroad properties, he saw the need for steamboat connections to Central and South America. Florida fascinated him, and he correctly saw it as a great winter vacation area. Tampa became the center of his new world. He had visited Florida years before with an ailing wife and came to see that it was neither a water wilderness nor a land of swamps, alligators, and mosquitoes, as so many northerners assumed. Meanwhile, his railroad empire expanded into a 1,000-mile system and he expanded steamship operations to Cuba. Plant decided a deluxe hotel was needed to bring more affluent tourists to his sunshine resort and built the lavish Tampa Bay Hotel in 1891. The Hotel Seminole was next constructed in Winter Park, also on Florida's west coast. After his death in 1899 Plant's steamboat lines were merged into Henry Flagler's Peninsula and Occidental Steamship Company. Plant's railroads became part of the Atlantic Coast line.

Henry M. Flagler (1830–1913) was another northerner who became impressed with Florida's warm winter climate. Like Plant, Flagler believed better hotels and transportation could draw wealthy tourists from the northern states. He, too, first visited with an ailing wife, in 1878. They found the ancient city of St. Augustine (1565) quaint but run-down. His attachment to the Sunshine State grew during a visit with his second wife in 1883. Development of the area became his new passion, and raising capital to do so was not a problem. Flagler was a wealthy man, having been a close associate of J. D. Rockefeller and vice president of the Standard Oil Company for many years. He purchased the local railway and put it into firstclass order. At the same time, he built a large hotel in St. Augustine, the Ponce de Leon, which became a marvel of its day because of its concrete construction. When it opened early in 1888 it was seen as the beginning of the winter season for America's first families. As the bitter memories of the Civil War gradually began to fade, northerners felt comfortable in going south for part of the winter season.

Flagler began to extend his railroad south along Florida's east coast. In 1889 it reached Daytona Beach, and within five years it entered West Palm Beach. More hotels followed the railroad's steady progress. Those seeking a little sun in January were soon heading south to patronize Flagler's domain. Briefly Flagler felt he had ventured as far south as necessary, but an unusually cold winter in 1894–1895 prompted him to consider an extension to Miami, which at the time was a forlorn fishing village. In 1880 there were only 257 residences in most of South Florida. The magic of Flagler's money soon transformed Miami into the pride of Biscayne Bay.

Meanwhile, Flagler started operation of the Florida East Coast Steamship Company and like his counterpart, Henry Plant, was engaged in coastal shipping. Boats ran to Key West, the most southern island in the United States; other lines served Nassau, Cuba, and Savannah. By 1904 Flagler was feeling his years but decided to make one last, grand extension of the Deep South transportation empire. He would build a railway to Key West, which in effect meant laying a track over the sea. Much of the line was built on concrete bridges as the railroad hopped from one island to the next. It was a daring and expensive project that required seven years to complete and cost upward of $20 million. The line opened on January 12, 1912. Flagler died in May of the following year feeling that his life's mission had been completed. The Florida East Coast Railway operated ferry boats directly to Havana from Key West, making travel from East Coast cities like New York an almost effortless experience. However, a powerful hurricane in 1935 put an end to the overseas railway; the damage was so severe that the line was abandoned. It was soon rebuilt into a highway that extended Route U.S. 1 to Key West. In more recent years new, wider bridges were built to improve the highway, but many of the original railway bridges still stand to one side of the new roadway.

PANAMA PACIFIC TRAVEL

Europeans began to explore the Pacific Ocean and the western coast of the Americas in the early sixteenth century. Magellan's men cruised along the Mexican coast in 1521. Francis Drake explored the coast of California fifty-some years later. It was not until 1776 that Spanish clergy opened a mission in San Francisco. Two years later Captain Cook discovered the Sandwich Islands, which are today the state of Hawaii. At the end of the American Revolution the British Navigation Acts no longer hampered American sailors, who began to search the globe for new markets. In 1783 a sloop from Hingham, Massachusetts, visited Canton, China, and a few years later there were fifteen U.S. vessels in the China trade whose cargoes of tea, silk, spices, and sandalwood made a few American merchants wealthy. As the waters of the Pacific became more familiar, whalers ventured around the south end of South America to hunt the oil-rich giants of the sea. Long before the United States claimed any land on the West Coast, John J. Astor opened a fur-trading post on the Columbia River in 1811. By the 1840s America was fussing with Britain over Oregon and with Mexico over California, winning both land disputes without major warfare, if the brief war with Mexico can be forgotten.

By early 1848 America owned what we now call the lower forty-eight and became a vast nation that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific. However, most of the land west of the Mississippi River was thinly populated. There were no large cities, and the towns already settled were very small. San Francisco, San Diego, and Los Angeles were small villages. There was no mail service to the east, and the telegraph did not arrive until 1861. Few settlers seemed attracted to this beautiful but remote region. Richard Henry Dana was one of the few Yankees to visit the Golden State before the gold rush. He sailed around the horn of South America to California on the brig Pilgrim in 1833 and wrote about the hardships of being a sailor in Two Years before the Mast. His book was complimentary to California, but it hardly encouraged a rush to the West Coast. Early in 1848 a nugget of gold was discovered in a branch of the American River not far from Sacramento. News traveled slowly from this isolated area, and few Americans knew about it for almost another year when President Polk mentioned the golden nugget in his State of the Union address. In a matter of days every able-bodied man in the nation wanted to be in California. Where there had been no demand for transportation to the West, there was now a desperate demand for ships. There were no existing boat lines to that part of the world. Boats came and went on an as-needed basis, to haul lumber or hides in slow-moving (non-naval, non-troopship) merchantmen or to carry the more profitable high-class goods from China. They were not set up for passengers, and most of the captains did not want passengers on board their vessels no matter what the demand.

The crowds at the dock were handled in a disorganized manner by more speculative owners who saw this unexpected enthusiasm for westward migration as an opportunity for quick profit. Any available ship was pressed into service, whether she was ready for such an extended voyage or not. The first to leave is said to be the J. W. Coffin, a bark that left Boston on December 7, 1848. She was followed by another 774 vessels, both sail and steamer, that had been pressed into service to meet the sudden demand. In all, nearly 100,000 people headed to the gold fields. Few had a pleasant or safe journey, but these men were possessed by a gold fever that had affected their judgment.