![]()

BORROWED TIME

The mood in the capital to which the generals returned in November 1644 had a new hostility towards them. Until now, newspapers and pamphlets could on the whole be relied upon to cry up parliamentarian successes and minimize defeats; and as Cromwell knew better than most, the accomplishments of individual commanders could be eulogized beyond what seems now to have been their objective desserts. Now the opposite effect obtained, centred above all on the events of 9–10 November, when the royal army had twice challenged Parliament’s commanders to battle and they had twice refused. There was a strong (and false) impression that those commanders had still heavily outnumbered their enemies, by at least two to one, which made their conduct seem even more pusillanimous, or even disloyal.1 Mercurius Civicus spoke of their ‘improvidence and imprudence’.2 The Parliament Scout noted that some attributed the failure to the absence of the earl of Essex, others ‘that our generals are godly but not worldly men, others speak of plot and betrayal, others God’s judgement for our being too worldly’.3 A Perfect Diurnall talked darkly about a forthcoming punishment of mistakes.4 The Scottish Dove belied its name, declaring that God’s anger had clearly been aroused by the presence of traitors or wrongdoers in the parliamentarian ranks, who needed to be rooted out.5 In his private journal, a London merchant and landowner called Thomas Juxon, who was fervent both as Puritan and parliamentarian, wrote that ‘God seems not to favour the great officers’ and that ‘our great army is now shamefully beaten and cudgelled out of the field’.6

Faced with this suspicion and hostility, the returning generals had two immediate options: to form a united front and persuade public opinion of the necessity for their actions, or to blame each other and hope that somebody else would become the scapegoat. Depending on the outcome of either tactic, there were three possible scenarios for the fighting season in 1645: that the existing system of military leadership would be vindicated and maintained; that one or two generals would be replaced and the rest retained; or that a clean sweep would be made of the lot. Cromwell’s future was prospectively in this melting pot, along with those of the rest.

FURORE

The policy initially adopted by the military leaders was to try to allay the anger in the capital by taking collective responsibility for the campaign and explaining plausibly why the decisions taken had been rational and wise. This was entrusted to Sir Arthur Hesilrig, who duly appeared in the House of Commons on 14 November, rather theatrically still attired in his battlefield dress of a leather buff coat, sword and pistols. He explained the decisions taken at Newbury as the product of a prudent weighing of odds in the prevailing circumstances; and got nowhere. The Commons remained unpersuaded and unappeased, and the demands for better explanations continued.7 It did not help their feelings when the commander of the troops which had been driven from the siege of Basing House when the army retired to winter quarters wrote complaining that he had been betrayed and abandoned.8 On the 22nd, Cromwell and Waller arrived in the Commons, to be greeted with an unwonted coldness and to be observed as looking unusually subdued as a result. The following day the House formally ordered them to prepare a justification of their actions on the campaign.9 From what followed, it is clear that this was the tipping moment, as the two men decided that the fastest and most effective way of allaying the anger of Parliament and the public was to offer them a scapegoat.

They chose the earl of Manchester, Cromwell’s own immediate superior, as the fall guy, and the reasons for this may readily be surmised. Oliver’s rank as the earl’s lieutenant put him in a privileged position to deliver information concerning his commander’s shortcomings. As said, his own relations with Manchester had deteriorated to the point at which it seemed unlikely that they could work together much longer, while Waller may well have blamed the earl for not marching rapidly into the west to reinforce him in September, and so leaving him to make his humiliating retreat before the king. Moreover, Manchester was vulnerable. He had already gained a reputation as a torpid and over-cautious commander by the early summer, and had come close to being disowned or bypassed by the Committee of Both Kingdoms for his failure to obey its orders to take rapid action in the autumn. At the battle in October, he was handily isolated on the eastern side of the terrain, enabling Waller, Cromwell and Hesilrig to unite in blaming him for their lack of decisive success in the west. He had certainly (as was now to be shown) argued strongly for avoidance of battle when the king offered it in November. The facade of solidarity was already cracking in the army, and Manchester being isolated and set up for attack, as letters were being sent from officers to London, claiming that on 10 November Cromwell, Waller, Hesilrig and Essex’s officers had all wanted to give battle to the royalists, but had been overruled by the rest of the council of war. The earl was really the perfect choice, and it must be imagined that Cromwell was encouraged and supported in it by frantic discussions conducted with his own friends and allies in Parliament and the armies before he delivered his blow. Moreover, Oliver was the perfect person to deal it. He had a savage streak in his nature which enjoyed inflicting death, injury or humiliation on those against whom he had taken, and he had already played a crucial part in bringing down Hotham and Willoughby, two other inadequate upper-class commanders. In Willoughby’s case in particular, he had destroyed a general’s reputation by delivering a set of falsehoods to the Commons. Manchester’s fall was designed to be a larger version of that lord’s.

The blow was dealt on 25 November, when Cromwell and Waller made their reports. Nobody subsequently commented on Waller’s speech, so it must be surmised that it was relatively brief and supportive of Cromwell. The latter spoke for a long time, and caused a sensation. His delivery was, like many of his orations, extremely emotional, laced with tears. It was also deadly in its aim and intention, because it charged Manchester not merely with incompetence but with a consistent and deliberate design to sabotage Parliament’s war effort by preventing decisive victory. He did so by telling a string of lies and distorted truths. First he accused the earl of frustrating his army’s wish to besiege Newark after Marston Moor, when the records of the Committee of Both Kingdoms show that Manchester had sought exactly this. Then he alleged that his commander had single-handedly frustrated the design to march his army to attack Prince Rupert at Chester, when the same records prove that the earl was supported by his officers in objecting to this and eventually agreeing to a compromise plan. That was prevented by Essex’s defeat, and now Cromwell portrayed Manchester as delaying his army’s progress to rescue the military situation in the south from the beginning. In fact he had marched at top speed to protect London, and only slowed down there because of his very real fear that the strategy being forced upon him was too dangerous. Cromwell accused his superior of halting his army in Hertfordshire in September for no reason, when he knew that Manchester was struggling to resolve the religious divisions in it, and its lack of pay and equipment, before heading for battle.

The volley of accusation went on. Oliver naturally made full play with the earl’s genuine resistance to his orders to make for Dorset and engage the king there with Waller. He then told stories of Manchester’s foot-dragging and obstruction all through the Newbury campaign. He accused him of preventing decisive victory in the battle by sending in his crucial diversionary attack far too late, though, as said, there is no sign that the king was able to divert any soldiers from that wing to reinforce the other. Thereafter, Manchester was charged with preventing the pursuit of the fleeing royalist army after the battle, and then an advance into the Oxford area to prevent it from reuniting, and then the interception of the royal army on its return to relieve Donnington. The decision not to attack it when Rupert offered the chance was laid firmly at his door, as was that to abandon the siege of Basing House and give up the whole campaign. Oliver’s version of events included a ringing and emotive account of an exchange in the council held in the cottage on the morning of 10 November. It claimed that when Cromwell and others argued for an immediate attack to win a decisive victory, Manchester had replied ‘if we beat the king ninety-nine times he would be king still, and his posterity, and we subjects still, but if he beat us but once we should be hanged’. The clear implication was that the earl did not think it worthwhile fighting at all.10

Cromwell also excused the performance of his own horsemen in the battle as the result of the terrain, as described, and candidly acknowledged that he and most of his men favoured independency, and some might be Anabaptists, but that they had been accepted only as good and faithful soldiers who fought well.11 He promised that they would peacefully accept a presbyterian settlement, if one were imposed.12 The whole thing worked, as Oliver’s speeches to the House often did. It provoked a long debate, which kept MPs sitting far into the afternoon,13 but was generally received, as the newspaper reports cited below demonstrate, with satisfaction and approval. One journal writer who heard of it at second hand spoke of Cromwell’s ‘clearness and ingenuity’.14 It must have helped that he was clearly supported not just by Waller, but also, now, by the latter’s lieutenant Hesilrig.15 It was the sort of thing that most of the Commons wanted to hear: that the failure of the campaign had not been due to the will of God, or collective and sequential misjudgements, but because of one bad apple in the barrel of commanders.

Formally, the House’s response was to refer the relations made by both Cromwell and Waller to a committee with a remit to consider a remodelling of the parliamentarian armies, chaired by an MP called Zouch Tate. It had powers to cross-examine Cromwell, Waller and Hesilrig, and send for papers from the Committee of Both Kingdoms. Two days before, the committee itself had been ordered by the House to consider ways of combining the existing armies into a single body as large as possible.16 Press responses were mixed. Some accepted that Cromwell was now fully vindicated and exonerated, reporting the satisfaction he had given the Commons: these tended, of course, to be papers already approving of him.17 Others disapproved of the rift that Oliver had just opened in the parliamentarian leadership and declined to report his speech: these included one which favoured independency.18 Manchester had suspected that Cromwell might turn on him, and his countess had reputedly made a last-minute attempt to head this off, inviting Cromwell and his civilian ally Sir Henry Vane to supper on the previous night and telling Oliver that her husband ‘did exceedingly honour and respect him etc’. He was said to have replied, dourly, ‘I wish I could see it’.19 Cromwell may have expected that the earl’s reaction to the subsequent attack on him by his most important and famous subordinate officer would be as choleric as most of Manchester’s responses to slights or obstructions, but even he may have been surprised by its strength. On 26 November the earl asked the House of Lords to permit him to defend himself, and two days later he delivered his response, which like Cromwell’s speech was long and detailed.20

There were three aspects to it. The first was a dignified and thorough rebuttal of Cromwell’s accusations, pointing out the inaccuracies and injustices of those concerning his behaviour between July and October as has been done above. He covered his part in the decisions taken on the Newbury campaign by saying, again correctly, that in every case they had been the product of a majority of votes on the army’s council of war, of which his was only one. Likewise, his actions when sending in the attacks on the eastern end of the royalist position during the battle were all taken on the advice of his senior officers, who were named and all prepared to testify to this fact. He was also right in pointing out how poorly Cromwell’s own cavalry had performed both at the battle and on the morning of 9 November. When discussing the crucial meeting of the council of war in the cottage on the following morning, he insisted that it had been Hesilrig, and not he himself, who had uttered the words beginning ‘if we beat the king ninety-nine times . . .’ and that though Manchester had supported him, neither had been referring to the war in general. Instead they meant that if they defeated the king north of Donnington that day, he could shelter the remnant of his force behind his powerful local garrisons (as he had done two weeks before), whereas if their army was destroyed, then there was nothing to stop the victorious monarch immediately advancing upon London.

1. This may be the earliest portrait of Cromwell (bottom row, second from left), a crude but still distinctively individual woodcut on a broadsheet published in August 1646. It was a catalogue of Parliament’s victories in the Great Civil War then concluding, in a manner which emphasized the achievements of the more aristocratic and conservative generals, such as the earls of Essex and Manchester, and downplayed Cromwell’s.

2. Cromwell’s home town of Huntingdon would have been perfectly familiar to him in this painting of one corner of it from the end of the eighteenth century: the medieval parish church and houses, and the sprawling Ouse with its animal and human activity, are not changed from his time.

3. A view of Ely, painted around 1800, again shows virtually no change from the sight which would have greeted the young Cromwell from that angle. The medieval cathedral still rides on its hill above the Ouse, like a great vessel, and dominates the landscape physically, politically and religiously.

4. The grammar school in Huntingdon, in which Cromwell was taught by Thomas Beard: part of a former medieval hospital, and now the Cromwell Museum.

5. A nineteenth-century print of a contemporary miniature of Cromwell’s mother, a person generally respected for her piety, modesty and common sense, and consistently supportive of her son without interfering in his career.

6. Sir Oliver was the leader of the dynasty of which our Cromwell led a junior branch. His portrait displays the prominent nose which was a family trait, and his wealth – which Sir Oliver was to dissipate – is suggested by the elegance of his dress.

7. A miniature, painted from life, of Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth at the time of her husband’s period as head of state. Her modesty, unpretentiousness and seclusionrp from politics were as valuable to him as her devotion, and theirs was an enduringly happy marriage.

8. Cromwell’s Cambridge college of Sidney Sussex, drawn near the end of the seventeenth century, with its original central court unchanged from his time there near its beginning.

9. This is a highly imaginative eighteenth-century depiction of the wedding of King Charles with his French queen, Henrietta Maria. It does however sum up the dual aspect of the union: a usually happy and fertile royal marriage, but also a political liability, in that the wife whom the king deeply loved was a fervent member of the Roman Catholic faith feared and hated by most of the British.

10. This Victorian history painting depicts the entry of Cromwell into the House of Commons when first elected to Parliament in 1628. It conveys well the crowded and informal, and simple, seating arrangements in the chamber. He would probably not have stood out as much, in sober black clothing and linen collar, as he is made to do here.

11. Another Victorian artist recreates the dramatic scene, which Cromwell would almost certainly have witnessed, which closed the 1628–9 Parliament, when members resisted the king’s dissolution of it and held down the Speaker to pass some final motions. It incidentally provides a nice view of the end of the chamber as it was at the time (and until the nineteenth century).

12. The Victorian painter Ford Madox Brown achieved this splendid painting of Cromwell imagined at the nadir of his fortunes in the 1630s, as a working tenant farmer at St Ives. The Ouse Valley landscape is authentic, as is the crowding of incidental rustic detail, and our man’s air of depression and introspection may well be also.

13. Another nineteenth-century reconstruction of a dramatic moment in parliamentary history for which Cromwell would almost certainly have been present, Charles I’s attempted arrest of the Five Members in January 1642. Again, it gives a good sense of the layout of the House of Commons, although there would have been more benches and people.

14. Sometimes Victorian history painting erred on the side of drama. This famous representation of Cromwell’s cavalry action at Marston Moor conveys its frenetic action and the armaments well, but to enhance its protagonist’s heroic credentials it loses the co-ordinated discipline of a close-order attack, and gives Cromwell a wound in the arm, rather than the neck.

15. Some Victorian history paintings are so fine that they can readily be forgiven inaccuracies. Augustus Egg’s famous scene of Cromwell kneeling in prayer on the night before the battle of Naseby puts him and his men in nineteenth-century military tents, when he would have been quartered in a house or cottage (and the moon was not full); but it is so atmospheric that it remains a beautiful work of art.

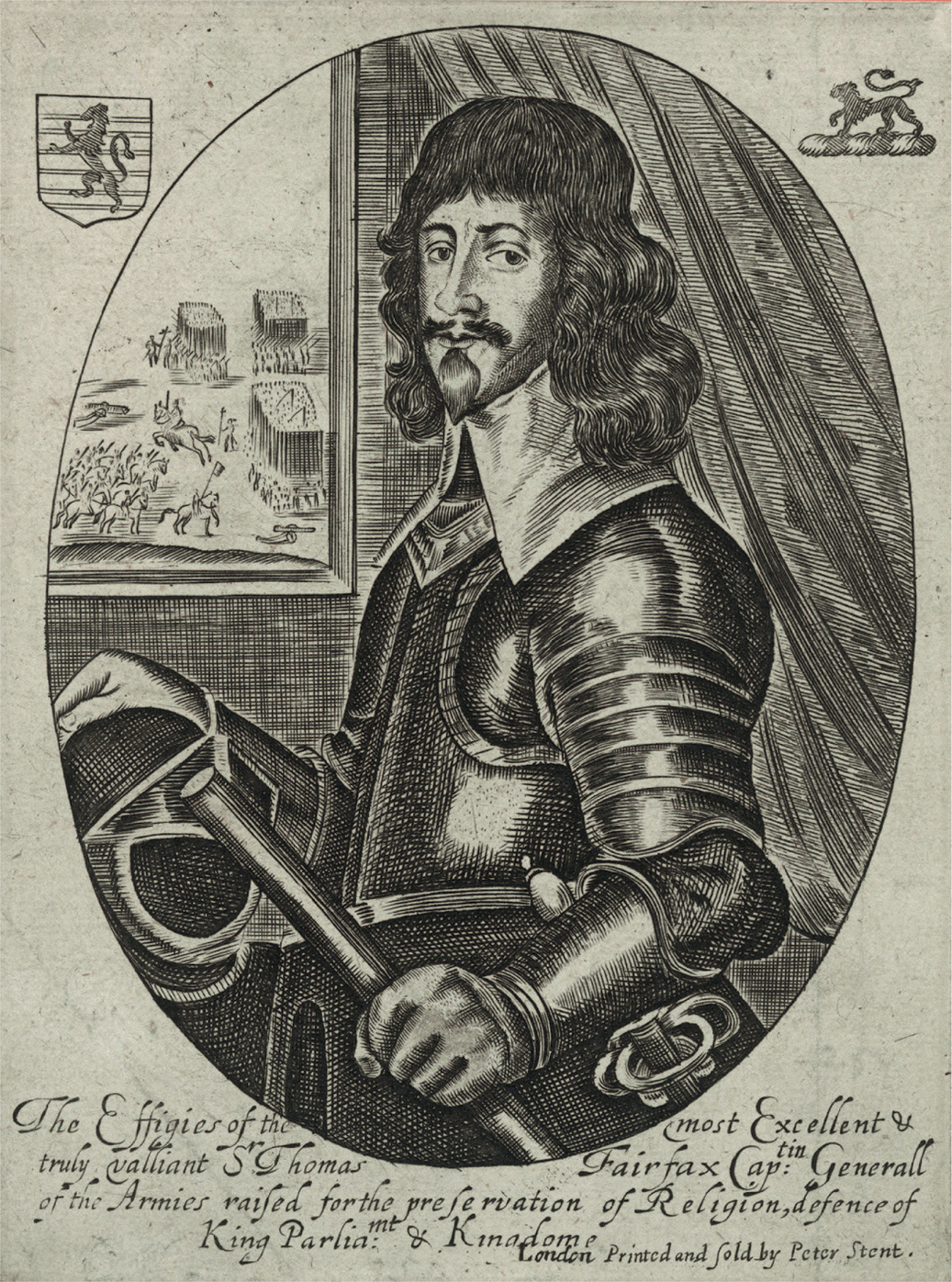

16. Sir Thomas Fairfax became Cromwell’s most reliable military and political ally in Parliament’s war effort, and his immediate commander in the last year of the war. This contemporary engraving captures his dash, flair and energy, and also his blade-like nose and long, dark, thick and waving hair.

17. Henry Ireton was another of Cromwell’s most loyal and reliable allies, though this time a junior one and client: he was his deputy in governing Ely and commanding the New Model Army cavalry, and eventually became his son-in-law. This portrait, painted years later, displays his stubbornness, courage and dedication, bonded by a firm Puritan faith which matched Oliver’s.

18. Robert Streater’s famous plan of the battle of Naseby, first published in 1647, is an admirable guide to the layout of the armies there, though it may increase the actual size of the royal army.

19. A Victorian history painting of the battle of Naseby seems to capture the alleged moment when a Scottish noble caught the bridle of King Charles’s horse and so prevented him from leading in the royalist reserve and possibly turning the action in his favour.

20. A nineteenth-century illustration of the storming of Basing House by Cromwell’s men in October 1645 embodies well the sheer chaos and violence of the event, which ended in the destruction of the house and the deaths of many defenders.

Thus far, the earl of Manchester was largely in the right in objective terms, and had been sober and restrained, but there were two other elements in his defence which were to explode the political situation instead of stabilizing it. The first was that he admitted that he had come sincerely to believe that God did not intend either side to gain an outright victory in the war, and that a negotiated peace was to be the divinely ordained outcome. He did not say when he had reached this conclusion – it was most probably after the defeat of Essex at Lostwithiel, following that of Waller and balancing the great victory at Marston Moor – but he had articulated it in the debate on 10 November if not before. In this situation, he believed that the main strategic imperative was to keep Parliament’s main armies intact, and thus never to fight unless at an advantage, so as to retain a strong position from which to bargain for good terms. This was a dramatic admission, and coupled with the earl’s emphasis on his own inexperience as a general, and reliance on the advice of his more experienced subordinate officers and of councils of war, must have given an abiding impression of a timid and torpid commander. Moreover, his stance was not of a kind likely to reassure many religious independents, whose vision of a future church structure was most unlikely to be acceptable to the royalists and would almost certainly be one of the main casualties of a negotiated peace.

What really made his presentation political dynamite, however, was that he did not merely set out to counter Cromwell’s accusations, or to accuse him in turn of specific failures of military performance, but to return the compliment and attempt to destroy his reputation altogether, politically as well as militarily. He accused him of trying to undermine Manchester’s authority in the Eastern Association army during the Newbury campaign by telling the men that the earl was responsible for their continuing long service in autumnal conditions and that Cromwell would have led them home long before. More generally, the earl appealed to conservative and moderate opinion by representing his lieutenant-general as a dangerous radical. He described Cromwell’s pressure on him to dismiss all opponents of independency, above all Crawford, from their army, and went further to claim that Oliver had spoken of being willing to fight the Scots to prevent an intolerant presbyterian settlement, and use his soldiers to prevent a treaty with the king that established one; and had expressed contempt for the Westminster Assembly. Yet more incendiary was the earl’s insistence that Oliver had inveighed against the power and privileges of the nobility and expressed his desire to overturn it. All this was to play to the very worst prejudices of those who feared the socially transgressive potential of religious radicals. Whereas most of Cromwell’s accusations against Manchester can be checked against contemporary records (and found wanting), the most serious of those made against him by the earl in return – the invective against nobles and the willingness to fight his own allies to protect independency – cannot be independently verified. Both are extensions of attitudes which Cromwell certainly held: his fierce advocacy of independency and his irritation with inept aristocratic commanders such as Grey of Groby and Willoughby, which must have been compounded by Essex’s defeat at Lostwithiel and Oliver’s growing estrangement from Manchester himself. Cromwell was also noted, all his life, for intemperate outbursts, from the time when one ruined his youthful political career at Huntingdon. How much the earl exaggerated, however, it seems that nobody can say. What is clear is that he was accusing Oliver of treason as effectively as Oliver had accused him: a commotion over the conduct of a campaign had turned into a political vendetta.

His fellow peers mostly heard the earl of Manchester with apparent sympathy, and formally referred his account to a committee of six, which carefully mixed men who were not currently likely to favour independency with those who were.21 It also asked the earl for a written version of his speech, which he duly delivered on 2 December. The House pronounced itself satisfied, and sent a copy to the House of Commons, which provoked another long speech from Cromwell, in which he tried to escalate the dispute to a new level by suggesting that by appearing to accept Manchester’s accusations against him the Lords had breached the legal privileges of MPs. A majority were inclined to agree with him, and it was resolved to set up a conference over the matter between the Houses. This was held on the 4th, and the two rival charges, Cromwell’s against Manchester and Manchester’s against Cromwell, were read out. Three days later, the Commons set up a committee of lawyers to decide whether the Lords’ behaviour over the earl’s accusations did indeed constitute a breach of privilege. The row was now starting to tear Parliament apart, horizontally as well as vertically.22 As these resolutions show, Oliver had succeeded in rallying considerable support in the Commons, among those who had sympathy with independency, those who were sensitive about their own House’s powers and privileges, and those who were simply convinced by his speeches.

There were, however, powerful forces building up against him and in favour of Manchester. A majority of the Lords, as described, had rallied to a fellow peer. The Scots by now identified the independents as the greatest barrier to their abiding dream, which had brought them into the war: to establish a presbyterian Church in England equivalent to that in Scotland, which would ensure religious uniformity and harmony between the two nations. They now took up Manchester’s cause as their own, persuaded by his speech. One of their clerical representatives in London wrote that it was time to break the power of independency by removing Cromwell from the army.23 It was rumoured that they had declared they would not fight for Parliament again until this was done. The earl of Essex, who still enjoyed a great reputation among parliamentarians and led a strong faction in both Houses of Parliament, also threw his weight behind his fellow aristocrat. He had long favoured a negotiated peace, on good terms, and was now prepared to ally with the Scots, and offer them a Church of England roughly on their model, to get one. He supported Manchester in the Lords, and it seemed inevitable that the presbyterian majority in the Westminster Assembly would also be favourable to the earl.24

A striking apparent insight into the forces moving against Cromwell, but also the limitation of their powers, is provided by a retrospective account left in the memoirs of a leading parliamentarian MP, lawyer and politician called Bulstrode Whitelocke. Long afterwards, he recollected that late one night at this time the earl of Essex had invited him, and another prominent lawyer and MP, John Maynard, to his mansion. There the two men found a gathering which combined the earl’s leading supporters in the Commons with the Scots commissioners. They sat down and the Scottish Lord Chancellor, the earl of Loudoun, said that Cromwell had to be removed, as a bitter foe of both the Scots and Essex. He sought the lawyers’ advice on how to do so, and Whitelocke claims they answered that Cromwell was a very able man with a large following in the Commons, and that it would be necessary to have solid proof of his misconduct – such as that he had deliberately tried to set English and Scots against each other – if any move against him stood a chance of success. They added that they were not aware of any such evidence. Essex’s greatest supporters in the Commons, Cromwell’s former ally Denzil Holles, and Sir Philip Stapleton, both thought that it could be found and a majority formed against Cromwell. The Scots were, however, persuaded that an open attack on him by their two groups in conjunction would be unwise unless undeniable proof of Cromwell’s misbehaviour could be obtained. The meeting broke up at 2 a.m., and Whitelocke believed that Oliver had a spy in it, because he was subsequently notably more gracious to the two lawyers.25

The controversy therefore remained thus far formally one between Cromwell and Manchester, and both mustered their supporters and witnesses, as manifested in subsequent written depositions. Cromwell’s view of his opponent was endorsed by several officers in the Eastern Association army who were under his command in the horse division, most or all of whom shared his enthusiasm for independency; but also by Waller and Hesilrig and some of their officers, and the commander of the siege of Basing.26 There were also dirtier tactics used by sympathizers: a libel against the record of both Manchester and Essex was scattered around London.27 Manchester was supported by some presbyterians in his army: Crawford, one of the earl’s chaplains, and an anonymous officer who had known Cromwell since the opening of the war in East Anglia and was almost certainly William Dodson.28 The first and the last of those robustly enlarged on Manchester’s portrait of Oliver as a dangerous and unscrupulous radical. Essex’s officers stood aloof from the fray. Everybody understood that although some of those engaged, like Waller and Hesilrig, may have chosen sides for tactical and fortuitous reasons, this was more than a spat between two generals. It was a dispute which fed off deep divisions between parliamentarians, linked to their instincts and beliefs concerning the proper conduct of the war, the nature of the religious settlement to follow it, and even the proper location of power within society.

It also mapped at points onto an emerging partisan landscape within Parliament.29 For the first two years of the conflict, there had been tension, and at times dispute, in both Houses between those whose preferred that an end to the fighting would be in a negotiated compromise, and those who wanted utterly to defeat the king and his followers. The latter tended naturally enough to be prepared to prolong the war further and make greater sacrifices in it, and wanted an eventual settlement which was less like that of the pre-war religious and political establishment. Most members were not firmly identified with either group, and support swung between them and individuals migrated between them according to changing circumstances. Cromwell of course was always firmly identified with the people who wanted outright victory and far-reaching reform. During the winter of 1644–5 these existing ideological and human groupings developed further, and acquired the nicknames of Presbyterians and Independents, transferred to them from the now opposed factions in the Westminster Assembly. The essential distinction between them remained that which had divided them before, but with some changes of policy and personnel. Those who would be happy with a negotiated peace, made as soon as possible, now allied firmly with the Scots, making a tightly controlled presbyterian Church close to the Scottish model a part of the intended deal. Essex and his allies and followers became a major component of this grouping, nicknamed Presbyterians. The Independents were those who took up the cause of winning the war outright and imposing a more radically novel settlement on king and nation, which would include a looser system of church organization, discipline and doctrinal orthodoxy. The labels did not necessarily reflect personal religious belief: there were, for example, plenty of individuals who were personally happy with a presbyterian Church but felt that religious independents should be given some latitude because of the importance of their contribution to the war effort. As before, most parliamentarian MPs and some peers cannot be allocated confidently to either group. Nonetheless, something like a rough, hazy and unstable partisan division was in place, and the emotions, instincts and reasons which were causing people to give support to either Cromwell or Manchester were often the same as those which had created it. This made the mud-slinging between the two men all the more dangerous, especially as it was on the verge of causing a feud between the two Houses themselves. At the very time at which Parliament needed dispassionately and forensically to decide on the lessons of the Newbury campaign, and the measures required to wage war better in 1645, it was in danger of tearing itself apart.

NEW MODELLING

The whole context of parliamentarian politics and the terms of debate were famously changed forever on 9 December, when a dramatically far-reaching and – to most observers – unexpected measure was introduced to the Commons. This was what became known as the Self-Denying Ordinance, a draft piece of legislation that would bar all members of either House from holding military or civil offices conferred by Parliament, for the duration of the war. At a stroke, this would sweep Cromwell, Manchester, Waller, Hesilrig, Essex and a list of lesser commanders out of the army, terminating their quarrels and making way for a new set of generals, commanding a new, consolidated, field army. It is clear from the context that it was intended to be a cross-party initiative. The proposal for it seems to have emanated from the Commons committee set up to consider the future form of the field army, to which Cromwell’s complaint against Manchester had been referred. It was the chair of this committee, Zouch Tate, a fervent presbyterian, who brought in the proposal as part of a report from the committee. He clearly did so with considerable trepidation: Whitelocke, who was there, commented that he carried in the document ‘like a boil on his thumb’.30 The plan was then supported by Sir Henry Vane, a leading Independent (in both the religious and political sense) and usually an ally of Cromwell, and then by Oliver himself, as part of a long debate in a very full House, more than two hundred MPs being present. The committee chosen to draft the ordinance mixed men from different groups, but a majority on it seem to have been Independents.31

Cromwell may have spoken more than once in the debate. It was said afterwards that he argued that unless the war were prosecuted effectively then the English people would say that MPs and Lords were keeping it going to profit from the offices they held in the machinery to fight it. He apparently proposed that the inquiry into the shortcomings of the campaign be dropped, and effort put instead into reshaping a consolidated army with new leaders, generously declaring that he had also made mistakes as a commander. He credited Parliament’s soldiers with fighting for a common cause and not for particular generals. His intervention was regarded as very important, and his words noted more than those of any other contributor to the discussion. They represented, indeed, a key component of the process by which the measure became accepted, being the first recognition, by one of the contestants in the quarrel which had broken out over the conduct of the war, that the dispute was too damaging to be pursued further and needed to be replaced by a radical remedy to the question of leadership. As ever, we are woefully lacking in any reliable record of the manner in which the idea for it was developed, and how early Cromwell’s engagement with it was, and how much he had to be persuaded into becoming an advocate.32 It seems reasonable to conclude that he would not have done so had he not come to believe both that his feud with Manchester was dangerous to the parliamentarian cause and that its outcome had become uncertain enough to endanger himself; or at least that his friends and supporters had developed these beliefs. There are no grounds at all for thinking that at the moment when the ordinance was proposed he was not aware that its enactment would almost certainly end his military career along with that of most of the other leading generals. It was clearly a sacrifice he was prepared to make, and we can never know how much considerations of altruism (of serving and saving the cause) or calculation (of rescuing himself from a potentially dangerous situation) played in his willingness to do so.33 The proposal for the measure was given widespread support in the press, and public opinion in London also seemed largely favourable.34

Thereafter, Oliver was engaged in four different areas of activity in Parliament and the capital, most of which ran through the rest of the winter and into the very beginning of spring. The first was to support the progress of the Self-Denying Ordinance and the measures which accompanied it and for a time took the place of it. Given his expressed views and loyalties, it must be presumed that he did this, though his own role is invisible. Between 11 and 19 December the ordinance passed through all its stages in the Commons, often with lengthy and heated debate. A proposal to exempt the earl of Essex from it was defeated by just seven votes, the earl’s supporters Holles and Stapleton acting as tellers for the minority and Vane and another prominent Independent acting for the majority: Cromwell’s support for the latter can be taken for granted. Another proposal, to deny office to anybody who did not take the oath of the Solemn League and Covenant and promise to submit to any form of church government that Parliament imposed – which would have worked against some of the religious radicals whom Cromwell favoured – was also defeated.35 On 7 January, however, the Lords rejected the whole ordinance on the grounds that to lead men to defend the realm was one of the fundamental purposes of an aristocracy.36

The Commons, their pride affronted, made an appeal to the Lords to change their minds, and when this failed, began to circumvent the noblemen by reconstructing the main field army with the presupposition that the ordinance would be in effect. On 11 January they decided that the army would have 6,000 horse in ten regiments, 1,000 dragoons in ten companies, and 14,400 foot in twelve regiments: this was a force of a size likely to outnumber anything the king could put into the field. Two days later they imposed the system of taxation needed to support a force of that size, the Eastern Association paying about half of the total. They also allocated funds to pay the Scottish army to advance south, giving an overwhelming numerical superiority when facing the royalist forces; in February these were secured against an extra property tax on the whole of parliamentarian territory, to be levied for four months. On 21 January the House voted to make Sir Thomas Fairfax, the military commander who had won the most victories among those not sitting in either division of Parliament, the leader of the new army. It did so by a comfortable majority, with a vote which this time opened along clearly partisan lines: Cromwell and Vane, both Independents, were tellers in favour of Fairfax, opposed by Essex’s men Holles and Stapleton, who were both emerging as leading Presbyterians. As a sop, the House directed Tate’s committee to find some mark of honour and recompense to award the displaced Essex. The latter’s experienced and respected foot commander, Philip Skippon, was appointed to lead the infantry in the new army, and the House also named the foot and horse colonels, again holding to the rule of appointing neither MPs nor peers. Of Cromwell’s existing horse officers, Fleetwood, Whalley and Vermuyden were all given regiments. A week later, Cromwell and Waller were both put onto a committee to frame instructions for the remodelled army.37

Tantalizingly, the post of general of horse in the new army was left vacant. Essex’s commander, Balfour, was dismissed, with the Commons directing that he should receive a suitable reward, but nobody was put into his place, apparently because there was no obvious candidate among the officers who was not apparently disqualified, like Cromwell, by a place in Parliament. The MPs seem to have decided to wait to see who would emerge. Everything now depended on whether the Lords would throw out the whole plan as they had the Self-Denying Ordinance. They debated it for the rest of the month, and sent up their amendments on 5 February, one of which was sent to discussion by a committee which included Cromwell. Debates over the requirements of the peers took up the next few days. A key one was that the lesser officers chosen by Fairfax should be approved by Parliament, and here once again the Commons divided along party lines, Cromwell and another Independent, Sir John Evelyn, acting as tellers for the votes against it and Holles and another Presbyterian, and Essex supporter, acting for its supporters. This time Cromwell’s side lost, by almost twenty votes, and he suffered another blow when the Commons agreed with the Lords’ requirement that all officers of the new army take the oath of the Solemn League and Covenant, and refusers be barred from any further post in Parliament’s service.

Oliver must have known that some of the more radical and scrupulous of the independents would jib at that. Not only did some sectaries scruple to take oaths, as said, but the terms of this one bound takers both to defend the king’s authority and to maintain a national Church and bring it into the closest possible conformity with that of Scotland, all undertakings about which some parliamentarians were starting to have doubts. However, the House also agreed to reject the Lords’ proposal that the soldiers would have to promise to accept any form of church government that Parliament imposed. On 13 February Cromwell and his allies returned to the attack, and a division in which he was once more paired with Evelyn as teller, against two Presbyterians, got agreement to strike out the clause purging army officers who refused the Solemn League and Covenant. Three days later, however, this was changed to a compromise with the Lords that subscription to the document was still needed to be admitted to a place in the army, especially as an officer. Such a concession was needed to get the Lords to agree to the ordinance for the new army and so set about creating the latter: people like Cromwell may have hoped that there was enough ambiguity in the terms of the League and Covenant to get it past the consciences of most officers. The day after that, the Commons set up a committee to consider how best to recruit what was becoming known as the New Model Army, and to get it ready to fight; and Oliver was made a member.38

The second of the four areas of activity in which Cromwell was engaged was his struggle with Manchester. The chance that the Self-Denying Ordinance would fail made it imperative that an alternative plan be followed to get rid of incompetent generals; and also both Cromwell and Manchester had names to clear from the mud-slinging in which both had engaged. Therefore, the inquiry into the failure of the Newbury campaign shuddered back into life just when it might have seemed as if the wholesale removal of the leading existing commanders ought to have rendered it unnecessary. On 26 December 1644 the Commons ordered a report into Cromwell’s conduct when the king came to relieve Donnington Castle, and a week later required one on Manchester’s conduct. On 10 January 1645 they humiliated both Manchester and Essex by peremptorily reprimanding them for not putting their soldiers into the winter quarters (closer to those of the royalists) specified by the Committee of Both Kingdoms. Soon after, they directed Manchester to submit to another of the committee’s orders, and on the 15th gave another direction for a report on the evidence submitted by Cromwell and Manchester.39

On 20 January, with the Lords still refusing to pass the Self-Denying Ordinance, the Commons raised the stakes in the quarrel by declaring that the action of the upper House in appointing a committee to hear Manchester’s charge against Cromwell was a breach of privilege, as Cromwell had wanted. A fresh initiative was launched to gather evidence to determine the truth of the charges that the two men had brought against each other. As a further act of aggression and intimidation, Tate’s committee was ordered to discover the printer of the defence of Manchester written by his chaplain, with a view to punishing him. Manchester promptly demanded a hearing, and the House insultingly left it to the committee to decide whether to give him one. On 12 February it went after the earl again, directing the committee to inform him of the charges against him.40 The third of Cromwell’s areas of activity this winter was finally to settle scores with an older and more clearly culpable parliamentarian opponent than Manchester. As soon as the autumn campaign finally ended, and all witnesses were available to return to London, the trials of Sir John Hotham and his son, who had been locked in the Tower for one and a half years, finally opened. The letters that the younger man had sent to the marquis of Newcastle, captured at Marston Moor, now served as the conclusive evidence for the prosecution, but as much more as possible was heaped up by it. Cromwell gladly appeared as one of its witnesses, citing the failure of the defendant to rout the opposing royalist wing at Belton as an act of deliberate perfidy; which it may have been, though final proof is lacking. Both Hothams were condemned to death, but the elder asked for a stay of execution, and both Houses allowed this on Christmas Eve. The Commons, however, only did so by ten votes, and while Holles and Stapleton acted as tellers for the victorious majority, Cromwell, implacable as ever towards enemies, was one of those for the minority who wanted severity. He got his way six days later, when the Lords asked that Sir John’s life be spared altogether because of his previous services. This time Cromwell and another Independent acted as tellers for the large majority which voted for death, Stapleton again being one of those opposed; and Hotham duly followed his son to face the headsman’s axe.41

Cromwell’s fourth area of activity between December 1644 and early February 1645 was to carry on his career as an MP and committeeman in general. He took up the teller’s staff for other motions than those mentioned already.42 Another major parliamentary initiative of the winter was to open and conduct peace talks with the king, a necessary measure to satisfy those in Parliament who wanted to end the war by treating. On 16 December Oliver was made one of the commissioners to hear the king’s reply to Parliament’s overture, and three days later was a teller in a vote to frame an answer. The division concerned showed that there was no consistent partisan frontier yet running through the Commons, for Oliver was paired with Hesilrig in favour of a motion that the MPs would reply ‘in time’ to the royal offer to discuss peace terms in detail. They were defeated, and Cromwell’s usual ally Vane was a teller for the victorious majority.43 Oliver was also serving on a range of parliamentary committees again.44 Outside Parliament he was able to attend the Committee of Both Kingdoms regularly for the first time since its establishment, being present for most of its meetings and getting put onto its sub-committee for the reshaping of the army. He also carried messages from it to the Commons.45

As an MP he also played his part in the continuing quest for a religious settlement, on which the collective mind of Parliament had been concentrated anew in early January by two further developments. One was a pointed letter from the representatives of the Kirk of Scotland, asking what progress had been made in the matter, on which the alliance between the two nations depended. The other was the action of the Westminster Assembly in handing Parliament the problem of how the independent and presbyterian models for the Church of England could be reconciled. On 14 January the Commons resolved that it was possible – in theory – for many different congregations to exist underneath a national presbyterian umbrella. Nine days later it decided that the Church should be divided into fixed congregations for public worship, each representing a certain number of dwellings and served by a minister who was part of the national system: in other words, equivalents to the traditional parishes. Representatives of a number of these were to meet together in a regional presbytery, and above these would come provincial organizations, classes, and national synods. The whole Church would be subject to state power.46 This was a system broadly equivalent to Scottish presbyterianism, but with state control, and the decisions still ducked the issues of where power ultimately lay in it, or how far the state would control it, or what would happen to congregations who did not want to be part of it.

In theory, the Self-Denying Ordinance would have allowed MPs to make themselves eligible for reappointment to high military office in Parliament’s army by resigning their seats: something that peers were of course not able to do as their nobility was inherited. There is not the slightest indication that either Cromwell or anybody else contemplated this course. To remain in Parliament not only ensured a place at the centre of power, which was not subject to the fortunes of war, but a role in the settlement of the nation after the war was won. There seems every likelihood, therefore, that Cromwell himself regarded the existence he was carrying on at Westminster and London in the first two months of 1645 as the pattern of his life in the foreseeable future: as a zealous and influential regular member of the Commons and the Committee of Both Kingdoms. It was going to take an extraordinary sequence of events to disrupt that; but such a sequence was not long in commencing.

THE INTERIM CAMPAIGN: THE WEST COUNTRY

The trail which was to lead Cromwell back to active military service began on 15 January, when the Commons decided to send a huge raiding party of six thousand horse and dragoons into the West Country, to disrupt royalist preparations for the campaigning season there. Sir William Waller was chosen to command it, because he knew the region and had done well there before, and as a final mark of honour to, and confidence in, him before he laid down his command and his men were reallocated to the New Model Army. He was, moreover, a general who had proved many times his ability to cover distances rapidly and catch enemies off guard, and could be a formidable strategist and tactician (though these talents too often seemed to abandon him on an actual battlefield). On the 29th, the House ordered him to join his troopers and commence his advance.47 Instead he stuck on the Surrey–Hampshire border, as only seven to eight hundred of the soldiers allocated to him from what had been Manchester’s and Essex’s armies had turned up.48

Waller’s mission acquired a new urgency and focus on 9 February, when local royalists recaptured the important Dorset port of Weymouth, which the earl of Essex had taken in the previous summer. They surprised it with the help of some of the citizens, in what became known as the Crabchurch Conspiracy, but the achievement turned out to be only partial. The parliamentarian garrison retreated into the twin town of Melcombe, on the far side of the harbour, and there held out under siege.49 On the 12th, Waller was therefore ordered urgently to march to its relief, and to secure Parliament’s other ports on the Dorset coast, Poole, Wareham and Lyme, if he were too late.50 Sir William’s problems were, however, continuing. He had no pay or supplies for his men, and no foot soldiers to accompany his cavalry and enable him to fight an enemy well supplied with both. On informing the Committee of Both Kingdoms of all this, he announced lugubriously and melodramatically, ‘I have discharged my conscience, and now if I perish, I perish!’51

Despite this declaration, he still did not set out, because he had run up against the instability among Parliament’s soldiers caused by their prospective incorporation into the New Model. In January some of Manchester’s infantry had started a petition to have him continued as their general, and when their colonel cautiously suspended two of the officers for promoting it, and sent them to London to face the earl himself, Manchester had restored them to their commands.52 In Waller’s case, most of his men for the expedition would be drawn from Manchester’s and Essex’s armies, and did not know him. Their resulting unease and resentment were enhanced by the prospect of more hard service without assured pay, and with the likelihood of once more sleeping rough in weather that, this early in the year, was likely to be both cold and wet. It was especially strong in Cromwell’s own huge horse regiment, around a thousand strong, which was to be a major component of Sir William’s force.53 As a leader, Oliver had two special and consistent talents. One served him especially well in Parliament, and it was his ability to make effective and persuasive speeches. The other was his success in instilling a profound personal loyalty into the soldiers who served directly under him. This was partly because of his concern for their physical welfare, their pay and the demands made of them and their horses on campaign. It must also have been because of the religious bond between him and many of them, in his protection and encouragement of independency. This bond between colonel and men much aided the good discipline of the latter, and their good performance under favourable conditions of battle. It was said that when a rumour had reached his troopers in January that they were going to be placed under the command of a Scot in the remodelling of the armies, they had immediately mutinied.54 Now they, as well as some of the horsemen from Essex’s army, mutinied again, refusing to obey Waller and embark on what seemed to them a foolhardy expedition with inadequate resources.55 They received sympathy from newspapers which favoured independency, and emphasized their normal high quality, loyalty and discipline.56

On 26 February, therefore, the Commons decided both to rescue the situation and pay Cromwell a final gesture of honour and trust, parallel to that granted to Waller, by ordering him to lead his regiment himself under Sir William’s command on the campaign. To remedy the material needs of his troopers, he was granted a thousand pounds.57 Oliver attended the Committee of Both Kingdoms for the last time on the following day, ensuring that care was taken to get the money paid over, and then set out to join his men.58 He did so with the two great advantages that Waller had lacked: he was known to and trusted by his regiment, and came with a chest of cash which would strengthen their faith in him still further. Conspiracy theorists might suggest that he had clandestinely encouraged his men in their behaviour towards Sir William, to secure just such a result; but apart from the (expected) utter lack of evidence for this, nobody suggested it at the time, and it would have been extraordinarily dangerous for him to have attempted anything of the sort. On 4 March the Commons ordered him and Waller to march for the West at once, with whatever men they had managed to gather already.59 A week later they had advanced across Hampshire with around four thousand troopers in all.60 All this dawdling had actually saved them a job, because in the meantime the parliamentarians in Melcombe, reinforced both by land and by sea, had sallied out, driven off their attackers and recaptured Weymouth.61

Their first action was the easiest, most successful and most newsworthy: to eliminate the royalist home guard for Wiltshire, being the horse regiment led by its high sheriff, Sir James Long. This was the sort of job at which Waller excelled: to trap and crush an outnumbered, unsuspecting enemy commanded by a genteel incompetent. He did it perfectly. The royalists were quartered in villages of the clay lowlands just to the west of the huge chalk wasteland of Salisbury Plain. Waller made a forced march from Andover along the high road to Amesbury, resting there in the evening. At midnight he sent part of his force, including Cromwell, to ride through the rest of the dark hours in an arc across the open sheep country of the south-west corner of the plain. By dawn on 13 March they were to the west and north of their prey, and attacked, driving the panicked royalists south and east, and so straight into the rest of Waller’s men who were ready for them. Of four hundred of Long’s men, only thirty escaped, the rest being killed, or captured with Long.62 This was exactly the kind of easy, complete, victory of which Parliament and its supporters wanted to hear. From there Sir William and Cromwell moved south through the chalk hills into Dorset, where they united with the local parliamentarian forces on the 19th to make up an army near to the six thousand which Parliament wanted.63

This is where things started to go wrong. To protect the royalist West Country against exactly the kind of havoc that the parliamentarians intended to wreak there, the king had returned to it what remained of the regional army which had been led in 1644 by Prince Maurice. This he had now put under George Goring, with whom he had also sent some of his best horse regiments from the royal field army. That gave Goring a striking force roughly equal to that which he now faced, and he was at least Waller’s equal in a cavalry warfare of raids, feints and forced marches. Moreover, he disposed of a large force of infantry, which Waller – despite frantic appeals for one – lacked, enabling him to conduct combined operations suited to a variety of terrain. The landscape of western Dorset and eastern Somerset, which was the zone in which the rival forces met, was a patchwork of woods, narrow roads between banks, and small enclosures, badly suited to mounted warfare and favouring the defence: in Waller’s own words, ‘every field was a fortification, and every lane as disputable as a pass’. He began to view fighting Goring as ‘my hopeless employment in the West’.64 His men faced this formidable new enemy worn out after their long marches across Wiltshire, and starting to run short of money and supplies.65 In the last week of March, Goring commenced an expert harrying of his opponents, pouncing on and routing all of the parliamentarian detachments, including Cromwell’s, west of Dorchester; and then refusing battle when his enemies combined again and offered it in a position favourable to themselves.66

Waller had found Cromwell an able and congenial lieutenant, thinking him blunt, but not proud or arrogant, and obedient, intelligent, and inclined to let others speak first in discussions of strategy rather than push forward with his own opinions.67 This does seem a fair summary of his character in general, and Oliver also had the strongest possible motive, after his treatment of Manchester, to show himself to be an effective and compliant subordinate. They should have made an excellent team, the very experienced, energetic and often talented general and the charismatic, committed and gifted cavalry commander. As it was, by the opening of April they were facing the wrong opponent, in the wrong place, with the wrong resources. In the first week of that month Waller and Cromwell gave up and retreated to Salisbury, and there they stuck, their activities fading out of the newspapers.68 At first the Committee of Both Kingdoms ordered Sir William to advance westwards again, but he did not, and on the 17th it directed him to march his men back to Reading, turn them over for integration into the New Model Army, and go on to London to resign his commission.69 It was an anticlimactic end to the campaign, and a gravely disappointing one to Sir William’s career as a parliamentarian general. Cromwell went with him, apparently expecting to do the same, and therefore almost certainly with the same bitter feelings regarding his own time as a soldier.

THE INTERIM CAMPAIGN: THE MIDLANDS

When Cromwell had ridden out from London on his spring campaign, there would have been yellow catkins on the hazels, grey buds on the willows and black buds on the ashes, but the trees in general would still have been leafless and the grass withered and bleached on the sheep runs. Now as he returned, spring was almost gone, with fresh grass in the fields and emerald leaves showing in sprays against the grey trunks of the woods, while flowers of half a dozen kinds had opened on the field banks and the floors of copses. The landscape of military leadership had been as dramatically transformed.70 In March there had been another struggle between Lords and Commons, this time over the list of officers which Sir Thomas Fairfax had submitted for their approval, to be commissioned into the New Model Army. The lower House had altered only a few names, but the upper one changed around a third, over half of them being from Manchester’s former army and many representing religious independents. This was a clear attempt to produce a less radical and potentially more tractable force, and the Commons rallied against it, inspired both by sympathy for independency and for soldiers with good records, and by a sense of collective pride. They coerced the peers by persuading the corporation of London to make the loan needed to launch the New Model conditional on the acceptance of Fairfax’s list. That then got through the Lords by one, proxy, vote wielded by Viscount Saye, both Essex and Manchester backing the defeated minority.

The New Model was now on the way, more or less in the image that Fairfax had wanted for it, and that made further resistance by the Lords to the Self-Denying Ordinance pointless. It was therefore revived by the Commons and passed by both Houses on 3 April, directing that by 13 May all members of either one who had been appointed to a military or civil office by them since 1640 had to resign. It went through, however, without any clause which forbade either House to appoint or reappoint any of its members to such offices in the future, so that if Fairfax and his new corps made a mess of things, some of the old generals might return. It therefore also left a chink of hope for a future military command for Oliver.71 For the time being, however, the old order was passing, and before Cromwell neared London most of the existing commanders, including Essex and Manchester, had handed in their commissions. The Commons spurred on Manchester to do so, and reminded him of the animosity of most of its members, by making a final declaration that he should answer the charges against him as a general.72 Several of the Scottish officers who had served Parliament and might have continued to do so preferred now to transfer to the forces of their own nation: one of them was Cromwell’s enemy Crawford, and Oliver must have been glad to see him disappear.73 Their removal reduced the influence of presbyterianism in the New Model further, and more changes allowed one more of the cavalry officers who had served under Cromwell, a noted religious independent, Nathaniel Rich, to become a colonel. Oliver’s shadow hung over the horse division of the new army, as six of the eleven regiments which now comprised it had been formed out of men he had commanded for the Eastern Association. Most of his own enormous regiment, on delivery to Fairfax, was divided into two of standard size, one being put under Cromwell’s lieutenant-colonel and cousin Edward Whalley and the other honoured by being made Fairfax’s own, though another leading officer in Cromwell’s old regiment, his brother-in-law John Desborough, was put in effective command.74

On 21 April Waller and Cromwell reported to Fairfax’s headquarters at Windsor to announce delivery of their men, debrief, and move on to London and civilian life. This is exactly what Sir William did, but Oliver, allegedly to his complete surprise, was offered another job.75 The king was still at Oxford, preparing to set out from there on his summer campaign, but most of his field army was either in the west with Goring or with Rupert and Maurice in the Welsh Marches, reimposing royalist authority there. The Committee of Both Kingdoms decided that Cromwell should move on immediately with the cavalry force he had commanded under Waller, including both the new units just formed out of his old regiment. His assignment was to prevent the king from joining the bulk of his soldiers, and trap him in Oxford.76 It was a vital duty, and represented just the kind of rapid, mobile warfare at which Cromwell excelled, and at which Fairfax knew he excelled after their service together in the previous two years. It was also a providential opportunity to end his military career with a resounding success instead of an anticlimax; or perhaps even to extend it.

As soon as he received these instructions, Oliver called his horsemen to a rendezvous at Watlington, a village sitting at the foot of the steep chalk scarp of the Chiltern Hills, upon the plain of the River Thames. It was easily reached from their quarters around Reading, and from it he marched at once towards Oxford, using intelligence given by the parliamentarian garrison at Abingdon, a major thorn in the side of the king’s winter quarters, aided by four friendly Oxford University students. He quartered north of the city for the night, and in the morning was attacked by a smaller party of royalist horse, which he drove back, claiming to have captured two hundred men and four hundred horses, and killed some troopers. Having thus cleared the way, he pounced on a nearby royalist outpost in a mansion called Bletchingdon House, threatening the governor with a massacre if he did not surrender at once. The unfortunate man had women guests in the house, and only two hundred soldiers, and was taken by surprise and without hope of relief; and the place does not seem to have been strongly fortified. As a result, near midnight he agreed to hand over the house and the weapons and ammunition in it and march away, bagging Cromwell a second easy and newsworthy victory, and over two hundred muskets. On the following day, 25 April, he sent a triumphant account of his success to the Committee of Both Kingdoms, meticulously attributing all the credit to God.77 When the former governor reached Oxford, the king had him court-martialled and shot for dereliction of duty.78

Later that same day, Cromwell led his men westwards across the Thames Valley to block the king’s escape from the city towards his field army, and once more excellent intelligence directed him towards easy prey: three hundred royalist foot soldiers who were marching between local garrisons. He caught them at the little town of Bampton an hour before midnight, and offered them the choice between surrender and death, accepting their submission at dawn. He then sent a party to beat up a royalist horse detachment on the march to the west, and settled at Faringdon, a safe distance south-west of Oxford, where he could still block King Charles’s way out. He wrote again to the committee, announcing yet more achievements and asking for money for his men, as they had to take free quarter.79 Parliament and the press were delighted, and the Commons duly sent formal thanks for his ‘great services to the state’.80 The easy victories, however, had now run out. Faringdon contained a great house which had been made another of the king’s garrisons, and Cromwell summoned it with the same blood-curdling threats which had broken the nerve of the hapless governor at Bletchingdon. Faringdon Castle, as this mansion was called, was another tough nut like Donnington, set within powerful earthworks with projecting bastions, and commanded by a hard-bitten veteran. He invited Oliver to send in his men to get killed, and this is exactly what happened. Cromwell despatched a large body of foot soldiers loaned from the Abingdon garrison to storm the defences at 3 a.m. on 30 April, and they were driven back with serious losses. He was reduced to thanking the governor for the kindness of allowing the survivors subsequently to carry away the corpses of their comrades.81

The unfortunate infantry from Abingdon were commanded by Richard Browne, a solid and capable man who was the governor of that town and Parliament’s major-general in the region. He and they had been sent by the Committee of Both Kingdoms to give Cromwell a foot division, and the committee directed Fairfax to send more New Model soldiers to join him.82 Trapped in Oxford, the king had sent appeals to Goring and Rupert to rescue him, and both were on their way with powerful bodies of men.83 The plan of the committee was to make Cromwell and Browne strong enough to repel them, and keep Charles cooped up. The flaw in it was that Goring was moving much too fast and was upon Cromwell and Browne with three thousand horsemen before the reinforcements could set out, while Rupert and Maurice were approaching the west of Oxford with another powerful force. Goring reached Faringdon on 3 May, and exactly what happened there must remain in doubt, because the partisan accounts differ. Royalists asserted that he fell successively on the soldiers of Cromwell and Browne, and those sent by Fairfax to aid them, and routed both with heavy losses.84 Parliamentarians insisted that Oliver drew up his men to fight him and Goring declined battle, though some admitted to the loss of a scouting party, and that the royalists beat up some of the quarters in which Cromwell lodged his troopers.85 What is certain is that Cromwell and Browne retreated eastwards to the comparative safety of Abingdon, leaving Goring in control of Faringdon and the king free to march. The royalist cavalry general had thwarted Cromwell’s mission in the Oxford area as effectively as he had Oliver’s one in the West Country a month before. Only peripheral damage had been inflicted on the royalist war machine, which had been balanced in large part by the loss at Faringdon Castle. The king’s departure on campaign had been delayed by at most one to two weeks, which was not a factor in the fortunes of war to come.

Charles left Oxford on 7 May and combined the men he took with him with those brought by Goring and Rupert, to make up a formidable army of eleven and a half thousand men. Halfway across the Cotswold Hills Goring peeled off with his three thousand to protect the West Country again, while the king and Rupert turned north to relieve the major royalist port of Chester, which was under siege. They picked up more soldiers from garrisons on the way. By 15 May the royal army was in Worcestershire, clearing away the enemy garrisons there with ten thousand men.86 Meanwhile parliamentarian leaders generated a spray of suggestions for a strategy to cope with it. The one besieging Chester begged the Committee of Both Kingdoms to join to his men the Scottish army in the north, Lord Fairfax’s in Yorkshire, and Cromwell and Browne’s one, to form a composite force large enough to take on the king.87 Parliament itself agreed that the Scots had to march south to face the royal army.88 Cromwell himself informed the Commons that he and Browne were going to follow the king in his rear and do their utmost to hinder him.89 As Oliver’s commission as a general was due to expire in the following week, under the terms of the Self-Denying Ordinance, and as he and his men currently had a critically important role to play, it was imperative to grant him an extension of it. On 10 May both Houses rushed one through, until 19 June.90 A few other, local, commanders, such as Lord Fairfax, were granted the same privilege, given the gravity of the situation.91

Cromwell’s strike force consisted of the horse regiments with which he had raided around Oxford, plus four of the New Model Army’s foot regiments, sent by Sir Thomas Fairfax, and Browne’s men and some from Midland garrisons. Together they totalled six to eight thousand, not enough to match the royal army alone but capable of making up a body able to do so if united with the Scots and more local parliamentarian commanders. They accordingly marched up into the Midlands, crossing the limestone hills which divide Oxfordshire from Warwickshire to quarter in various parts of the latter county and wait for opportunities and allies. They did not come.92 The parliamentarians besieging Chester gave up that job and retreated in the face of the king’s continued advance, appealing for help.93 Lord Fairfax and the other northern parliamentarians did not feel strong enough to face the royal army without the Scots. The Scots, meanwhile, having moved down from Newcastle into Yorkshire, instead of joining him and heading on south as asked, went in the wrong direction, across the Pennines into Westmoreland.

They were prodigal in reasons and excuses. The Scots claimed to have heard that Charles intended to invade the north via Lancashire, to reconquer the region and attack Scotland, and so were moving into his path. They claimed to lack pay and food for their men, and carriages and draught horses for their baggage and equipment, and they could not move without those. They claimed that the New Model Army was now getting paid every fortnight a larger sum than they had received from Parliament in six months.94 In reality, two considerations seem to have prevailed with the Scots more than any others. The first was that they were watching their own backs. In the previous autumn a civil war had broken out in Scotland, produced by a royalist rebellion in the Highlands led by the marquis of Montrose. The latter had notched up a succession of brilliant victories, and though he had not yet broken into the Lowlands, it seemed increasingly possible that he would, and that the Scots in England would have to return home to fight him. So they had an incentive to stay close to the border. The second probable motivation was that they had a keen respect for, and fear of, the main royal field army, and after their experience at Marston Moor did not want to face a situation in which they had to take it on alone or in combination only with Lord Fairfax’s men, who had failed them there.

This was, in fact, exactly the fate which Prince Rupert, as direct commander of the royal army under the king, intended for them. His master plan for the 1645 campaign had been to reconquer the north, sweeping up there before the New Model was ready, relieving the remaining royalist strongholds and annihilating or chasing off the local parliamentarians and the Scots, while they were separated and vulnerable, and then turning south again, reinforced by northerners, to face the New Model.95 The response which Parliament now intended was to halt the royal army in the North Midlands with an allied one made up of the Scots and the soldiers of Lord Fairfax and Cromwell and Browne. That would fight a replay of Marston Moor, and if it would be smaller than the composite force which had won that battle, the royal army was also now less than that which Rupert had led there. Instead, now, the Scottish retreat had left the component parts of the intended allied force far apart from each other, each too weak to tackle the king by itself and vulnerable to annihilation by him. Charles and Rupert could now rampage as they wished. The bitter truth of that must have sunk into Oliver as he was forced to dawdle in Warwickshire while the woods, fields and heaths of that county turned fully green around him.96 He lacked any money for his men, so that they had to take free quarter again, and feed their horses on the sown grass now sprouting in the meadows, on which the farmers depended for their hay.97

Parliament, and its executive, the Committee of Both Kingdoms, now had to play its trump card, the New Model Army. In the first half of May, when it trusted to its putative allied army to stop the king, it had sent Sir Thomas Fairfax and most of that army into the West Country, to relieve Taunton. This town, taken by Essex in the previous summer, sat in the centre of the royalist territory of the region and presented a major threat to it. The response by the king’s followers was to try to reduce it as fast as possible, an enterprise which would, if successful, release a reinforced western royalist army to march east and distract Parliament or join the king and give him a composite field force at least the size of the New Model. Accordingly, Parliament needed to keep Taunton in its own hands, and Sir Thomas Fairfax duly marched into Dorset and sent a relief party which saved the town in the nick of time.98 In mid-May Parliament and its committee seemingly decided on a new strategy to trap and destroy the king’s army, by making his capital, Oxford, play the role that York had done in the previous summer. They ordered Sir Thomas to take the main body of the New Model to lay siege to the city, apparently to force the king to return to save it.99 He could then be brought to battle outside it and defeated exactly as Rupert had been outside York.

The committee now set to work to enact this scheme, and Cromwell found himself being moved as a piece in it, at the committee members’ behest; an experience which could not have been improved by the irony that one result of the Self-Denying Ordinance had been to enable former generals such as Essex and Manchester – now with no love for Oliver – to take up their seats on it and join the business of ordering him around. The first plan was to send him and his cavalry to reinforce the Scottish army, both strengthening it significantly in an arm in which it was always weak and adding to the moral pressure on it to come south. The combined force was expected to shadow the royal army and fight it if it could be caught at a disadvantage.100 That was scuppered when the Scots made it plain to their English allies that Cromwell was now so obnoxious to them that they would not fight alongside him.101 His orders were therefore changed, to hand over most of his horsemen and dragoons – 2,500 men in all – to one of the colonels serving under him, the Dutch professional Bartholomew Vermuyden. The latter was much more acceptable to the Scots, and would lead his party north to join them instead of Cromwell: if Vermuyden performed well on this mission, it seemed likely that he would be appointed to the vacant post of lieutenant-general of the horse in the New Model. Oliver was directed instead to come south with Browne and unite their remaining soldiers with the New Model Army, under Sir Thomas Fairfax, for the siege of Oxford. He and Vermuyden parted at Coventry, and Cromwell marched to Fairfax with a thousand horsemen and the foot regiments.102 On 21 May the New Model Army laid siege to Oxford.103 The implications of the change of plan were probably clear to Oliver, with the clock ticking against the extension of his military career. Sent north to the Scots, he would almost certainly have needed a further extension to carry out the expected service. As one among Fairfax’s subordinates, in a static and possibly lengthy siege – for Oxford was even stronger, better supplied and well defended than York had been – he would probably just wait uselessly until his time expired, and then return to London a civilian.