Chronological Notes of Historical Meetings

Ramparts Magazine—The Children of Vietnam

As human beings, we sometimes are confronted with experiences which render us substantively different individuals than we were prior to exposures.

Vietnam had this effect upon me. It was soul shattering—first, because of what was done to those innocents, and secondly because we, the American people and our tax dollars, caused it under the self-serving lies and greed which underlay the atrocities. Virtually every war crime imaginable was committed against this ancient people and their children.

These victims are embedded in my being. Dr. King wept when he was confronted with the images, but the history and its narrative, which moved him to oppose the war in 1967, should be remembered, and is without doubt, a part of his legacy.

Reprinted from the January Issue of RAMPARTS Magazine

Additional reprints available from RAMPARTS, 301 Broadway,

San Francisco, California 94133

Reprints: “Children of Vietnam”

1-10 copies … … … 35 cents

11-50 copies … … … 30 cents

51-100 copies … … … 25 cents

101-1000 copies … … … 20 cents

over 1000 … … … … 18 cents

(freight cost additional)

Photographs and Text by William F. Pepper

Preface by Dr. Benjamin Spock

A MILLION CHILDREN have been killed or wounded or burned in the war America is carrying on in Vietnam, according to the estimate of William Pepper. Not many of them even get to hospitals, which are few and far between, but when they do, they may lie three in a bed or on newspapers on the floor. Flies are in the wounds. Even such simple equipment as cups and plates are in short supply. Materials for the adequate treatment of burns—gauze, ointments, antibiotics and plasma—are usually non-existent. This contrasts with the incredible speed and efficiency with which American troops napalmed by mistake are given elaborate first aid while being lifted out of the battlefield and then flown to a Texas hospital for treatment.

When Terre des Hommes, a Swiss humanitarian organization, asked for American government assistance in flying burned and wounded children to Europe for repair, our officials refused. With crocodile tears they explained children are unhappy when separated from their families. The fact is that a third of all Vietnamese children in institutions have already lost both parents or been abandoned.

Can America, which manufactures and delivers the efficient napalm that causes deep and deforming burns, deny all responsibility for their treatment?

Many American physicians are now volunteering to treat the children if they are brought to America. But citizens must be asked to pay the bill for transportation and hospitalization. They will also have to persuade our government to allow the children to be brought here.

WILLIAM F. PEPPER, executive director of the New Rochelle Commission on Human Rights, instructor in Political Science at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York, and director of that college’s Children’s Institute For Advanced Study and Research, spent between five and six weeks this spring (1966) in Vietnam as a freelance correspondent accredited by the Military Assistance Command in that country, and by the government of Vietnam.

During that period, in addition to traveling, he lived in Sancta Maria Orphanage in Gia Dinh Province and in the main “shelter area” in Qui Nhon, for a shorter period of time. His main interests were the effects of the war on women and children, the role of the American voluntary agencies there and the work of the military in civil action.

His visits took him to a number of orphanages—among them: An Lac, Go-Vap, Don Bosco, Hoi Duc Anh, Bac Ai—hospitals: Cho-Ray, Holy Family, Phu My, Saigon-Cholon (central hospital) and shelters in Saigon, Cholon, Qui Nhon and outer Binh Dinh.

Mr. Pepper interviewed, frequently, the following Cabinet ministers of South Vietnam: Dr. Nguyen Ba Kha, Minister of Health; Dr. Tran Ngoc Ninh, Minister of Education; Mr. Tran Ngoc Lieng, Minister of Social Welfare; Dr. Nguyen Thuc Que, High Commissioner for Refugees.

In addition, he conferred with the leaders of the Voluntary Agency Community and the USAID Coordinator for Refugee Affairs, Mr. Edward Marks, as well as the USAID child welfare specialist, Mr. Gardner Monroe, with Mademoiselle E. La Mer of UNICEF and Mr. Pierre Baesjous of UNESCO.

As Mr. Pepper makes clear, by far the majority of present refugees in South Vietnam have been rendered homeless by American military action, and by far the majority of hospital patients, especially children, are there due to injuries suffered from American military activities. The plight of these children and the huge burden they impose upon physical facilities has been almost totally ignored by the American people.

—From remarks before the Senate of the United States, August 22, 1966, by the Hon. Wayne Morse.

FOR COUNTLESS THOUSANDS OF CHILDREN in Vietnam, breathing is quickened by terror and pain, and tiny bodies learn more about death every day. These solemn, rarely smiling little ones have never known what it is to live without despair.

They indeed know death, for it walks with them by day and accompanies their sleep at night. It is as omnipresent as the napalm that falls from the skies with the frequency and impartiality of the monsoon rain.

The horror of what we are doing to the children of Vietnam—”we,” because napalm and white phosphorus are the weapons of America—is staggering, whether we examine the overall figures or look at a particular case like that of Doan Minh Luan.

Luan, age eight, was one of two children brought to Britain last summer through private philanthropy, for extensive treatment at the McIndoe Burns Center. He came off the plane with a muslin bag over what had been his face. His parents had been burned alive. His chin had “melted” into his throat, so that he could not close his mouth. He had no eyelids. After the injury, he had had no treatment at all—none whatever—for four months.

It will take years for Luan to be given a new face (“We are taking special care,” a hospital official told a Canadian reporter, “to make him look Vietnamese”). He needs at least 12 operations, which surgeons will perform for nothing; the wife of a grocery-chain millionaire is paying the hospital bill. Luan has already been given eyelids, and he can close his mouth now. He and the nine-year-old girl who came to Britain with him, shy and sensitive Tran Thi Thong, are among the very few lucky ones.

There is no one to provide such care for most of the other horribly maimed children of Vietnam; and despite growing efforts by American and South Vietnamese authorities to conceal the fact, it’s clear that there are hundreds of thousands of terribly injured children, with no hope for decent treatment on even a day-to-day basis, much less for the long months and years of restorative surgery needed to repair ten searing seconds of napalm.

When we hear about these burned children at all, they’re simply called “civilians,” and there’s no real way to tell how many of them are killed and injured every day. By putting together some of the figures that are available, however, we can get some idea of the shocking story.

Nearly two years ago, for instance—before the major escalation that began in early 1965—Hugh Campbell, former Canadian member of the International Control Commission in Vietnam, said that from 1961 through 1963, 160,000 Vietnamese civilians died in the war. This figure was borne out by officials in Saigon. According to conservative estimates, another 55,000 died during 1964 and 100,000 in each of the two escalated years since, or at least 415,000 civilians have been killed since 1961. But just who are these civilians?

In 1964, according to a UNESCO population study, 47.5 per cent of the people of Vietnam were under 16. Today, the figure is certainly over 50 per cent. Other United Nations statistics for Southeast Asia generally bear out this figure. Since the males over 16 are away fighting—on one side or the other—it’s clear that in the rural villages which bear the brunt of the napalm raids, at least 70 per cent and probably more of the residents are children.

In other words, at least a quarter of a million of the children of Vietnam have been killed in the war.

IF THERE ARE THAT MANY DEAD, using the military rule-of-thumb, there must be three times that many wounded—or at least a million child casualties since 1961. A look at just one hospital provides grim figures supporting these statistics: A medical student, who served for some time during the summer at Da Nang Surgical Hospital, reported that approximately a quarter of the 800 patients a month were burn cases (there are two burn wards at the hospital, but burned patients rarely receive surgical treatment, because more immediate surgical emergencies crowd them out). The student, David McLanahan of Temple University, also reported that between 60 and 70 per cent of the patients at Da Nang were under 12 years old.

What we are doing to the children of Vietnam may become clearer if the same percentages are applied to the American population. They mean that one out of every two American families with four children would be struck with having at least one child killed or maimed. There is a good chance, too, that the father would be dead as well. At the very least, he is probably far from home.

When Wisconsin Congressman Clement Zablocki returned from Vietnam early in 1966, he reported that “some recent search and destroy operations have resulted in six civilian casualties to one Viet Cong.” Though Secretary of Defense McNamara challenged the figure, Zablocki, relying on American sources in Saigon, stuck by them, and sticks by them today. What he didn’t say is that in any six “civilian casualties,” four are children.

McNamara, too, is sometimes more candid in private. A colleague of mine attended a private “defense seminar” at Harvard in mid-November, and heard the defense secretary admit, during a question period, that “we simply don’t have any idea” about either the number or the nature of civilian casualties in Vietnam.

Perhaps because we see them only one at a time, Americans seem not to have felt the impact of our own news stories about these “civilian casualties.” A URI story in August, 1965, for instance, described an assault at An Hoa:

“I got me a VC, man. I got at least two of them bastards.” The exultant cry followed a ten-second burst of automatic weapon fire yesterday, and the dull crump of a grenade exploding, underground. The Marines ordered a Vietnamese corporal to go down into the grenade-blasted hole to pull out their victims. The victims were three children between 11 and 14—two boys and a girl. Their bodies were riddled with bullets…. “Oh, my God,” a young Marine exclaimed. “They’re all kids …” Shortly before the Marines moved in, a helicopter had flown over the area warning the villagers to stay in their homes.

In a Delta province, New York Times correspondent Charles Mohr encountered a woman whose both arms had been burned off by napalm. Her eyelids were so badly burned that she could not close them, and when it was time to sleep, her family had to put a blanket over her head. Two of her children had been killed in the air strike that burned her. Five other children had also died.

“They’re all kids,” wrote Veteran Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett, describing in September a battle at Lin Hoc. There, in a deep earth bunker below the fury of a fierce battle, a child was born. Within 24 hours the sleeping infant awakened—and choked on smoke seeping down into the bunker. According to Arnett, the GI’s had begun “systematically” to burn the houses to the ground, and were “amazed” as hundreds of women, children and old men “poured from the ground.” For the baby, how-ever, it was already too late.

Another Times correspondent, Neil Sheehan, described in June the hospital at Cantho, in the Delta region where fighting is relatively light. The civilians, he said,

come through the gates into the hospital compound in ones, twos and threes. The serious cases are slung in hammocks or blankets…. About 300 of the 500 casualties each month require major surgery. The gravely wounded, who might be saved by rapid evacuation, apparently never reach the hospital but die along the way.

A few months before, Dr. Malcom Phelps, field director of the American Medical Association Physician Volunteers for Vietnam, put the monthly figure for civilians treated at Cantho at about 800. That means at least 400 children, every month, in just that one hospital.

New Jersey doctor Wayne Hall, who worked at the Adventist Hospital in Saigon (he went at his own expense, as a substitute missionary surgeon), reported that over-crowding, even in this three-story Saigon institution, is a “chronic condition.” No one was ever turned down: “When there were no more beds and cots, they were put on benches; when there were no more benches, they were put on the floor. Some were lying on a stone slab in the scrub room—delivery cases.” Babies born on a stone slab. “Of course,” Dr. Hall added, “this is the extreme—but it’s a common extreme.”

AT THE OTHER END OF THE COUNTRY, in Northern I Corps, David McLanahan reported that during last summer, the 350-bed Da Nang Surgical Hospital never had fewer than 700 patients. McLanahan, one of five medical students in Vietnam on an intern program sponsored by USAID, said that Vietnamese patients frequently would not talk freely to him, but that they told Vietnamese doctors and medical students enough about how they got hurt so that it was possible to estimate that at least 80 per cent of the injuries were inflicted by American or South Vietnamese action.

My first patient [McLanahan said] was a lovely 28-year-old peasant woman who was lying on her back nursing a young child. The evening before, she had been sitting in her thatched hut when a piece of shrapnel tore through her back transecting the spinal cord. She was completely paralyzed below the nipple line. We could do nothing more for her than give antibiotics and find her a place to lie. A few mornings later she was dead, and was carried back to her hamlet by relatives. This was a particularly poignant case, but typical of the tragedy seen daily in our emergency room and, most likely, in all of the emergency rooms in Vietnam.

Most of McLanahan’s patients, he said, were “peasants brought in from the countryside by military trucks. It was rare that we got these patients less than 16 hours after injury. All transportation ceases after dark. A small percentage of war casualties are lucky enough to make it to the hospital.”

Cantho, Saigon, Da Nang, Quang Ngai—it is by putting together reports such as these that the reality of extrapolated figures becomes not only clear but plainly conservative. A quarter of a million children are dead; hundreds of thousands are seriously wounded. There must be tens of thousands of Doan Minh Luans.

Manufacturer Searle Spangler, American representative for the Swiss humanitarian agency Terre des Hommes, describes what his agency has found to be the pattern when children are injured in remote villages: “If he’s badly ill or injured, of course, he simply won’t survive. There is no medical care available. Adults are likely to run into the forest, and he sometimes may be left to die. If they do try to get him to a hospital, the trip is agony—overland on bad roads, flies, dirt, disease, and the constant threat of interdiction by armed forces.” McLanahan says that virtually every injury that reaches the hospital at Da Nang is already complicated by serious infection—and describes doctors forced to stop during emergency surgical operations to kill flies with their hands.

Torn flesh, splintered bones, screaming agony are bad enough. But perhaps most heart-rending of all are the tiny faces and bodies scorched and seared by fire.

Napalm, and its more horrible companion, white phosphorus, liquidize young flesh and carve it into grotesque forms. The little figures are afterward often scarcely human in appearance, and one cannot be confronted with the monstrous effects of the burning without being totally shaken. Perhaps it was due to a previous lack of direct contact with war, but I never left the tiny victims without losing composure. The initial urge to reach out and soothe the hurt was restrained by the fear that the ash-like skin would crumble in my fingers.

IN QUI NHON TWO LITTLE CHILDREN—introduced to me quietly by the interpreter as being probably “children of the Viet Cong”—told of how their hamlet was scorched by the “fire bombs.” Their words were soft and sadly hesitant in coming, but their badly burned and scarred bodies screamed the message. I was told later that they evinced no interest in returning to their home and to whatever might be left of their family.

I visited a number of the existing medical institutions in South Vietnam, and there is no question that the problems of overcrowding, inadequate supplies and insufficient personnel are probably insurmountable. The Da Nang Surgical Hospital is probably as well off as any Vietnamese hospital outside Saigon—but it is for surgery only; there is also a Medical Hospital not so well equipped.

Even in the Surgical Hospital, there are a number of tests that can’t be done with the inadequate laboratory and X-ray equipment. Frequent power failure is a major problem (suction pumps are vital in surgery rooms; one child died in Da Nang, for instance, because during an operation he vomited and—with no suction pump to with-draw the stomach contents from his mouth—breathed them into his lungs). Though 100 burn patients every month reach Da Nang Surgical Hospital, McLanahan reported that while he was there, the hospital had only one half-pint jar of antibiotic cream—brought in privately by a surgeon—which was saved for “children who had a chance of recovery.” In Sancta Maria Orphanage, I frequently became involved in trying, with a small amount of soap and a jar of Noxzema, to alleviate the festering infections that grew around every minor bite and cut.

In the nearby Medical Hospital, there are frequent shortages of antibiotics, digitalis and other equipment. While the Surgical Hospital makes use of outdated blood from military hospitals, most Vietnamese hospitals are chronically short of blood. According to another medical student, Jeffrey Mast, a hospital at Quang Ngai (60 miles south of Da Nang) occasionally “solved” a shortage of intravenous fluids by sticking a tube into a coconut—a common practice in outlying areas and, reportedly, among the Viet Cong.

The Swiss organization Terre des Hommes, which is attempting to provide adequate medical care for Vietnamese children (they were responsible for transporting Doan Minh Luan and Tran Thi Thong to England, and a few other children to other European countries), issued a report last spring Which said in part that in Vietnam,

hospitals … show the frightening spectacle of an immense distress. To the extent that one finds children burned from head to foot who are treated only with vaseline, because of lack of a) ointment for burns, b) cotton, c) gauze, d) personnel. In places with the atmosphere of slaughter houses for people, where flies circulate freely on children who have been skinned alive, there are no facilities for hygiene, no fans, and no air conditioning …

In South Vietnam, approximately 100 hospitals provide approximately 25,000 beds to serve the ever growing needs of the civilian population. Bed occupancy by two or three patients is not uncommon (two to a bed is the rule at Da Nang). I can testify personally to the accuracy of Manchester Guardian writer Martha Gellhorn’s de-scription of the typical conditions at Qui Nhon.

In some wards the wounded also lie in stretchers on the floor and outside the operating room, and in the recovery room the floor is covered with them. Every-thing smells of dirt, the mattresses and pillows are old and stained; there are no sheets, of course, no hospital pajamas or gowns, no towels, no soap, nothing to eat on or drink from.

“Americans in Vietnam who accidentally suffer serious burn injuries from napalm are rushed aboard special hospital planes … and flown directly to Brook Army Hospital in Texas, one of the world’s leading centers for burn treatment and the extensive plastic surgery that must follow. But burnt Vietnamese children must fare for themselves…”

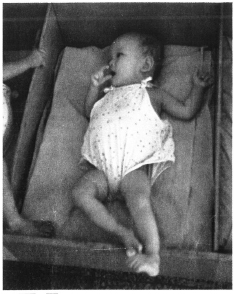

An abandoned child, his belly distended from malnutrition, sleeps on a doorstep in Saigon. Many of these children take their own lives.

“… virtually every injury that reaches the hospital at Da Nang is already complicated by serious injection … doctors are forced to stop during emergency operations to kill flies with their hands…”

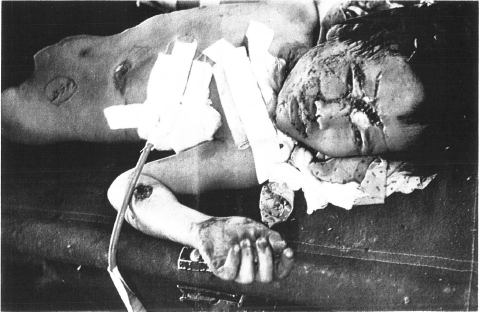

After superficial emergency treatment, a child—face and eyes torn by American shrapnel—awaits surgery at Da Nang. A lack of suction equipment—which would have kept him from inhaling the contents of his own stomach—killed him.

“Any visitor to a hospital, an orphanage, a refugee camp, can plainly see the evidence of reliance on amputation as a surgical shortcut”

“Torn flesh, splintered bones, screaming agony are bad enough. perhaps most heart-rending of all are the tiny faces and bodies scorched and seared by fire.”

“What we are doing to Vietnam may become clearer if the same percentages are applied to the American population.

They mean that one out of every two American families with four children would be struck with the tragedy of having at least one child killed or maimed.

There is a good chance, too, that the father would be dead as well. At the very least, he is probably far from home.”

Inside a Saigon hospital—some beds take three.

SEARLE SPANGLER, OF TERRE DES HOMMES, Says that there are only about 250 Vietnamese doctors available to treat all the civilians in South Vietnam. My own information is that there are even fewer; Howard Rusk of the New York Times gave a figure of 200 in September, and I have been told that there are now about 160. Obviously the difference hardly matters when at least five times that many children die every week. Dr. Ba Kha, former Minister of Health, told me that there are about nine nurses, practical and otherwise, and about five midwives for every 100,000 persons. He also told me that his ministry, charged with administering the entire public health program for South Vietnam, is allocated an unbelievable two per cent of the national budget.

There are, of course, American and “free world” medical teams at work, and USAID is increasingly supplying the surgical hospitals (a new X-ray machine has been installed at Da Nang, which AID hopes to turn into a model training hospital), but while their contribution is vital and welcome, it is like a drop in the ocean of civilian pain and misery. To speak of any of this as medical care for the thousands of children seared by napalm and phosphorus is ridiculous; there is simply no time, nor are there facilities, for the months and possibly years of careful restorative surgery that such injuries require. Burn patients receive quick first aid treatment and are turned out to make room for other emergency cases.

Although of course no one can talk about it openly, there are known to be cases in which pain is so great, and condition so hopeless, that the treatment consists of a merciful overdose. In an alarmingly large number of other cases, amputations—which can be performed relatively quickly—take the place of more complex or protracted treatment so that more patients can be reached in the fantastic rush that is taking place in every hospital. Any visitor to a hospital, an orphanage, a refugee camp, can plainly see the evidence of this reliance on amputation as a surgical shortcut. Dr. Hall has reported that hospitals allow terminal cases to be taken away by their families to die elsewhere, so that room can be made for more patients.

Then there are politics. A leading doctor and administrator in the I Corps area has found it difficult to get supplies for his hospital because he is suspected in Saigon of having been sympathetic to the Buddhist movement. In Hue, a 1500-bed hospital shockingly is allowed to operate under capacity because some of the faculty and students at the associated medical school expressed similar sympathies; apparently in punishment, the school and hospital receive absolutely no medical supplies from Saigon; only aid from the West German government keeps it operating at all. The dean of the medical school and some of his students were arrested last summer; a shipment of microscopes donated by West Germany was heavily taxed by Saigon. The harassment goes on.

At the present time, two groups are trying to do some-thing about the horror of burned and maimed Vietnamese children. They are the Swiss-based international group, Terre des Hommes, a nonpolitical humanitarian organization founded in 1960 to aid child victims of war; and a newly-formed American association with nationwide representation called the Committee of Responsibility. Their approaches are somewhat different, but they are cooperating with each other wherever it seems helpful.

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1965, Terre des Hommes arranged for about 400 hospital beds in Europe—like the two in England paid for by Lady Sainsbury—and for surgeons to donate their services. They contacted North Vietnam, the NLF representative in Algiers and the government of South Vietnam. The first two turned down the offer, but the South Vietnamese government seemed willing to cooperate. Air fare from Saigon to Europe is about $1500, so Terre des Hommes asked for help from the United States government.

American soldiers in Vietnam who accidentally suffer serious burn injuries from napalm are rushed aboard special hospital planes—equipped to give immediate first aid treatment—and flown directly to Brook Army Hospital in Texas, one of the world’s leading centers for burn treatment and for the extensive plastic surgery that must follow. Burnt Vietnamese children must fare for themselves.

It was the use of such special hospital aircraft that Terre des Hommes was hoping for, though any air trans-portation would have been welcome. Although American authorities in Saigon at first seemed enthusiastic, the decision was referred to the White House. In January 1966, Chester L. Cooper—now in the State Department “working,” he says, “on peace”—wrote on White House stationery to issue a resounding NO.

… the most effective way of extending assistance [Cooper wrote] is on the scene in South Vietnam where children and others can be treated near their families and in familiar surroundings…. U.S. aircraft are definitely not available for this purpose.

Terre des Hommes wrote back to Cooper to argue the absurdity of the American position—there are, of course, no “familiar surroundings” in napalm-torn Vietnam, thousands of the children are displaced orphans, and in any case there are no medical facilities for the long and difficult rehabilitation of burned children. In November of this year, asked directly about the request, Cooper said:

A doctor in Switzerland, of apparently good intentions but somewhat fuzzy judgment, wanted planes to take these innocent Vietnamese kids to Switzerland for treatment. [Edmond Kaiser, founder of Terre des Hommes, is not a doctor.] … The problem, basically, is that Terre des Hommes—and the chap involved, I want to emphasize, is a well meaning man—when we looked into it—and I worry just as much about the injured kids as the next fellow, maybe more so—what they want to do, they want to be taking these frightened little kids halfway across the world and dump them there in a strange, alien society …

However much better a Swiss home or hospital might be, it cannot compensate for having their own families around them in familiar surroundings in their own country. Experienced social workers and hospital workers have described what happens when you take a child suddenly out of his environment: culture shock and trauma….

Either Cooper is grotesquely misinformed about medical facilities and family coherence in South Vietnam, or he would genuinely rather keep these horribly maimed children in the bosom of frequently nonexistent families, in the “familiar surroundings” of dirty fly-ridden hospitals or jammed refugee camps or burned-out villages, rather than subject them to the culture shock and trauma of clean hospital beds, relief from pain, and a chance for the kind of surgery that will give a Tran Thi Thong back her eyelids and enable a Doan Minh Luan to close his mouth.

In any case, while the argument was going on, Terre des Hommes turned to commercial airlines and asked them to donate whatever empty space they might have on flights from Saigon to Europe; they refused, possibly feeling that the experience might be psychologically difficult for their other passengers. Finally, in May, Terre des Hommes brought 32 children (including Luan and Thong) out of Vietnam at its own expense; they were both sick and wounded, and eight were burn victims. The tiny victims were brought out by arrangement with Dr. Ba Kha, the Saigon Minister of Health; when I visited Saigon, the doctor was extremely cooperative and seemed eager to implement any program that could benefit even a few of the people who, he acknowledged, are suffering terribly.

IN SEPTEMBER, Terre des Hommes arranged for another 26 children to be flown to Europe, and one of their representatives in South Vietnam chose the children. But when the planeload arrived in Geneva, the people waiting received a terrible shock. It contained no war-wounded children at all. All 26 were polio, cardiac and cerebral spastic victims, chronically ill children. Dr. Paul Lowinger of Wayne State University’s medical school was on hand when Terre des Hommes officials learned what had happened, and described them to me as “disappointed and frustrated” over the violation of the terms of the agreement.

So far, no one has been able to determine what happened to the burned and other war-wounded children who were chosen by Terre des Hommes but somehow didn’t arrive on the plane in Geneva. They have, seemingly, disappeared—or died. I have letters in my possession indicating that physicians who have been to Vietnam since my return fear that wounded and burned children are being hidden or kept out of sight of visiting doctors.

In the meantime, Dr. Ba Kha had been replaced, apparently for his actions in attempting to get the burned children out of the country, and his successor has demonstrated much less concern for the Terre des Hommes project. Most officials of the Swiss organization are convinced, though they cannot of course say so publicly, that the firing of Ba Kha and the substitution of the children was directly related to the fact that in England and else-where in Europe, the arrival of the first group of children had caused a tremendous stir about the cruel effect of the bombing. The arrival of Luan and Thong in Great Britain stimulated a large, spontaneous flow of gifts and contributions—and not a small amount of indignation about their condition.

Incidentally, Canadian reporter Jane Armstrong, who visited the Sussex hospital where the two children are being treated, wrote that “the hospital staff have been astonished by their happy dispositions,” and notes that “no one can say what will happen to Luan,” who has no known relatives. The culture shock and unfamiliar surroundings don’t seem to be bothering the children.

In any case, Searle Spangler, Terre des Hommes representative in New York, seems firmly to believe in “spy-like hanky panky” by the South Vietnamese government, including the secreting of badly injured children in order to play down the problem. He also said that “some of our Vietnamese workers have been mistreated, and we have reason to fear for them.” On the adequacy of medical care in Vietnam, Spangler notes that Terre des Hommes operates the only children’s hospital in the country—600 patients for 220 beds, with many of the children lying on newspapers—and that in other hospitals, some news-papers and wrapping paper are commonly used as dressings for burns, being the only material available.

THE AMERICAN GROUP, the Committee of Responsibility, has only recently been formed. Its concern is specifically with children burned by American napalm and white phosphorus.

Its national coordinator and moving spirit, Helen Frumin, a housewife from Scarsdale, New York, became interested in the problem last spring when she encountered some Terre des Hommes material. Later, in Lausanne, she met Kaiser and learned more, about the, problem. She. became convinced that Americans have a special responsibility toward the burned children of Vietnam.

“Napalm is an American product,” Mrs. Frumin says. “The tragedy that is befalling children in Vietnam is all the more our responsibility where children burned by napalm are concerned; only the United States is using this weapon, and it is fitting that we should provide the care for the mutilated children.”

The Committee backs up its position by citing such sources as a story in Chemical and Engineering News, last March, about a government contract for 100 million pounds of Napalm B, an “improved” product. The older forms of napalm, the article goes on to say, left “much to be desired, particularly in adhesion.”

This, of course, refers to the ability of the hateful substance to cling to the flesh of the hamlet dwellers on whom it is usually dropped, insuring a near perfect job of human destruction after prolonged agony. It is because American tax dollars are behind every phase of the process, from manufacture to delivery and use, that the citizens of the Committee of Responsibility (who include prominent doctors throughout the country) feel that American dollars might best be spent in relieving the suffering they buy.

The Committee hopes at first to bring 100 napalmed children to America for extensive treatment. Hospital beds are being arranged, 300 physicians are ready to donate their services, homes have been found. But the cost for treating each child is still between $15,000 and $20,000, not including transportation from Vietnam to the United States.

The fantasy of the position that “adequate” care can be provided within South Vietnam and that “culture shock” might result from displacing a child, was pointed up in a report prepared for the Committee by Dr. Robert Gold-wyn, a noted Boston plastic surgeon. He said in part:

The children of Vietnam are the hardest struck by malnutrition, by infectious disease, and by the impact of terror and social chaos. They begin with the disadvantages implicit in a colonial society after nearly 25 years of continuing war, economic backwardness, inadequate food and medical facilities. Particularly helpless under such conditions is the burned child …

A burn is especially critical in a child because the area of destruction relative to total body surface is proportionately greater than that of an adult. And in the present real world of Vietnam, his nutritional status and resistance to infection is lower than that of an adult.

The acute phase of burn demands immediate and complex attention involving physicians, nurses, dressings, intravenous foods, plasma, often blood, antibiotics, and after the first week, wound debridement and skin grafting. Unless evacuation is simple and immediate and well-supervised, these early burns are best treated at or near the scene of injury.

… However, the child who has survived the initial stages of a burn would be a highly suitable candidate for treatment elsewhere. Since most of the burns are the result of napalm or white phosphorus, they are deep, and subsequent deformities and contractures are usual. These deformities, which interfere with function and offer extreme psychological obstacles for social read-justment, can be relieved by well-known and standardized plastic surgical procedures. These operations can ideally be done in a country such as the United States where facilities are adequate and where the environment is conducive to total rehabilitation.

The child would not have to lie in a bed with two or three others; he would not be exposed to parasitic infestation or sepsis or diarrhea or epidemics which are now prevalent in most of the Vietnamese civilian hospitals. He would be out of a war-torn country and could heal his psychological wounds as well.

… While one is instinctively reluctant to think of taking a child away from familiar surroundings, family and friends, for medical treatment and rehabilitation, these phrases are empty in the present context; we are talking of children whose homes are destroyed, who may be orphaned, whose “familiar surroundings” are the hell of disease, famine and flame attendant on modern warfare…. Further, the choice is not between care at home and better care in the United States, but in realistic terms, between token care or often, no care at all, and adequate care.

To Dr. Goldwyn’s analysis can be added that of Dr. Richard Stark, past president of the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, who agreed in a speech on October 3 that plastic surgical facilities in Vietnam are “presently inadequate.”

THERE IS, of course, an official United States position on the use of napalm in Vietnam. The Department of the Air Force set it forth on September 1,1966, in a letter to Senator Robert Kennedy:

A Vietnamese mother, herself and her child hungry, begs in the street, presenting her infant as appeal for aid.

“… there is the forgotten legion of Vietnamese children in the cities and provincial towns—clinging together desperately in small packs, trying to survive. Usually they have threadbare clothing, and sometimes they go naked; they go unwashed for months, perhaps forever; almost none have shoes.”

“In Sancta Maria Orphanage, I frequently became involved in trying, with a small amount of soap and a jar of Noxzema, to alleviate the festering infections that seemed to grow around every minor bile and cut.”

He was deformed by polio, but he stood in front of Saigon’s City Hall every day—shining shoes, staying alive.

The “pacification” program undertaken by the government of Premier Ky involves the relocation of large numbers of refugees from their ancestral homes to “New Life Hamlets The “hamlet” pictured here was built on top of a huge garbage mound.

“… I never left the tiny victims without losing composure. The initial urge to reach out and soothe the hurt was restrained by the fear that the ash-like skin would crumble in my fingers.”

“The shelter child receives little if any education. Crossed strands of barbed wire form the perimeter of his living world…“

“About eight per cent of Vietnam’s population live in refugee shelters or camps; about three quarters of the shelter population, or over 750,000 persons, are children under 16. In shelters like Qui Nhon, pictured here, there is unimaginable squalor and close confinement…”

“Despite the gradual process of animalization, in their striving to maintain a semblance of dignity, they are beautiful.”

Napalm is used against selected targets, such as caves and reinforced supply areas. Casualties in attacks against targets of this type are predominantly persons involved in Communist military operations.

I am compelled to wonder what military functions were being performed by the thousands of infants and small children, many of whom I saw sharing hospital beds in Vietnam, and a few of whom appear in photographs accompanying this article.

In the brutal inventory of maimed and killed South Vietnamese children one must also include those who are the helpless victims of American defoliants and gases. The defoliants used to deprive the Viet Cong of brush and trees that might afford cover are often the common weed-killers 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T. Yet the pilots spraying from the air cannot see if women and children are hiding in the affected foliage. These chemicals “can be toxic if used in excessive amounts,” says John Edsall, M.D., Professor of Biology at Harvard.

The U.S. has admitted it is using “non-toxic” gas in Vietnam. The weapon is a “humane” one, says the government, because it creates only temporary nausea and diarrhea in adult victims. Yet a New York Times editorial on March 24,1965 noted that these gases “can be fatal to the very young, the very old, and those ill with heart and lung ailments…. No other country has employed such a weapon in recent warfare.” A letter to the Times several days later from Dr. David Hilding of the Yale Medical School backed up this point: “The weakest, young and old, will be the ones unable to withstand the shock of this supposedly humane weapon. They will writhe in horrible cramps until their babies’ strength is unequal to the stress and they turn blue and black and die …” Once again, the children of Vietnam are the losers.

About eight per cent of Vietnam’s population live in refugee shelters or camps; about three quarters of the shelter population, or over 750,000 persons, are children under 16. In shelters like that of Qui Nhon, which I visited, there is unimaginable squalor and close confinement. There were 23,000 in that camp when I was there, and I have been told that the figure has since tripled.

Father So, unquestioned leader of these thousands of refugees in Qui Nhon and in the rest of Binh Dinh province, works for 20 hours a day to provide what relief he can, particularly for the orphaned children. These usually live in a hovel-like appendage to the main camp, frequently without beds. Food and clothing are scarce.

As So’s guest, I attended with him a meeting with Dr. Que, the South Vietnamese High Commissioner of Refugees, and with the USAID Regional and Provincial Representatives and the Coordinator of Refugees. So reminded the AID officials of their promise to supply badly needed food; the province representative replied that 500 pounds of bulgar had been given to the district chief with instructions that it was to be delivered to So for distribution in the camp.

So said nothing in reply. Later, he laughed softly and said to me that neither he nor the children would ever see that bulgar. The district chief had more lucrative connections.

THE SHELTER CHILD receives little if any education. Crossed strands of barbed wire form the perimeter of his living world. There are no sanitary facilities—those in camps near a river are lucky. Even shelters with cement floors have no privies for as many as 160 families. Plague and cholera increasingly threaten the health of the children (and of course the adults, though to a lesser degree), and I noticed an amazing amount of body infection on the youngsters, ranging from minor to extremely serious in nature. Their level of resistance is quite low, and the filth, combined with the absence of hygienic knowledge, is so universal that mosquito and ant bites quickly become infected. There is not usually medical help for the children of these camps. Tuberculosis and typhoid are evident, with periodic local epidemics; about one per cent of all Vietnamese children will have TB before reaching the age of 20.

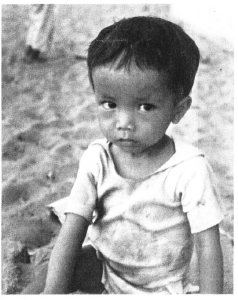

Many of the shelter children show traces of the war. I particularly remember a tiny girl whose arm had been amputated just below the elbow, and who followed me from one end to the other. The children also display a reaching out, not in a happy but in a sort of mournful way. The shy ones frequently huddle together against the side of a hut and one can always feel their eyes upon him as he moves about. No one ever intended for them to live like this—but there they are. One small child provided for me their symbol. He sat on the ground, a’way from the others. He was in that position when I entered and still there several hours later when I left. When I approached, he nervously fingered the sand and looked away, only finally to confront me as I knelt in front of him. Soon I left and he remained as before—alone.

Another 10,000 children—probably more by now—live in the 77 orphanages in South Vietnam. I lived for a time in Sancta Maria orphanage (in an area officially described as influenced by Viet Cong, and off limits to American military personnel). I arrived there during a rest hour, to find the children in a second floor dormitory, two to a bed, others stretched out on the floor. Their clothing consisted of only the barest necessities, though Sancta Maria was better oil than other institutions I visited.

Here, too, food was scarce and there was a shortage or a complete absence of basic supplies such as soap, gauze, towels and linen. I devoted some evenings to teaching elementary English vocabulary, and I was impressed by the amount of motivation displayed by some of these children despite, the horrors that frequently characterized their past—and present. Their solemnity was very real, however, as was their seeming general inability to play group games.

In most orphanages, as in the refugee shelters, there is no schooling at all, but despite this and the shortages of food and other supplies there is a growing tendency in Vietnam for parents to turn children over to the camps or to abandon them. Mme. LaMer, UNICEF representative to the Ministry of Social Welfare, expressed alarm over this tendency while I was in Vietnam; it seems to be one more example of the rapid deterioration of family structure because of the war. Officials told me that infant abandonment has become so common that many hospitals are now also struggling to provide facilities for orphan care.

FINALLY, THERE IS the forgotten legion of Vietnamese children in the cities and provincial towns—clinging together desperately in small packs, trying to survive. Usually they have at best threadbare clothing, and sometimes they are naked; they go unwashed for months—perhaps forever; almost none have shoes. They live and sleep on the filthy streets, in doorways and alcoves. Despite the gradual process of animalization, in their striving to maintain a semblance of dignity, they are beautiful.

On a few occasions I took an interpreter into the streets with me and spent hours sifting histories (often, feeling that my presence might inhibit the response, I stayed away and let the Vietnamese carry out the interview).

Some had come to the cities with their mothers, who turned to prostitution and forced the children into the streets. Others, abandoned in hospitals or orphanages or placed there while ill, had merely run away. Still others had struggled in on their own from beleaguered hamlets and villages. Once on the streets, their activities range from cab flagging, newspaper peddling and shoe shining to begging, selling their sisters and soliciting for their mothers. I saw five- and six-year-old boys trying to sell their sisters to GI’s; in one case the girl could not have been more than 11 years old.

WITH MISERY COMES DESPAIR, and one of its most shocking forms was called to my attention by Lawson Mooney, the competent and dedicated director of the Catholic Relief Services program in Vietnam. Mooney said he had noticed, between the autumn of 1965 and the spring of 1966, a fantastic increase in the rate of adolescent suicide.

I began to check the newspapers every day—and indeed, there was usually one, frequently more than one suicide reported among the city’s children. In several cases, group suicides were reported: a band of young people, unable to face the bleakness and misery of their existence, will congregate by agreement with a supply of the rat poison readily available in Vietnam, divide it, take it, and die.

“Many of these suicides,” Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Luan, Saigon Director of Police, told Eric Pace of the New York Times, “are young people whose psychology has been deformed, somehow, by the war.” Van Luan went on to say that in the Saigon-Cholon area alone, 544 people attempted suicide during the first seven months of 1966—many of them, of course, successfully. In that one section of the country—with about IB per cent of the total population—that is an average of 78 a month. Last year, Luan noted, the monthly average had been about 53, so the increase was about 50 per cent. “You must remember,” Luan went on, “that these are young people who have never known peace. They were more or less born under bombs.”

These are the “familiar surroundings” away from which American policy will not transport the horribly burned children of Vietnam, the “frightened little kids” of whom White House aide Chester Cooper says that humanitarians want to take “halfway around the world and dump them there in a strange, alien society.” One must agree with his further comment that “it is a very ghastly thing.” Clearly, the destruction of a beautiful setting is exceeded only by the atrocity that we daily perpetuate upon those who carry within them the seeds of their culture’s survival. In doing this to them we have denied our own humanity, and descended more deeply than ever before as a nation, into the depths of barbarism.

It is a ghastly situation. And triply compounded is the ghastliness of napalm and phosphorus. Surely, if ever a group of children in the history of man, anywhere in the world, had a moral claim for their childhood, here they are. Every sickening, frightening scar is a silent cry to Americans to begin to restore that childhood for those whom we are compelled to call our own because of what has been done in our name.

William F. Pepper is Executive Director of the Commission on Human Rights in New Rochelle, New York, a member of the faculty at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York and Director of that college’s Children’s Institute for Advanced Study and Research. On leave of absence last spring, he spent six weeks in South Vietnam as an accredited journalist.

In hospitals, wrapping paper and newspapers are commonly used as blankets, even as bandages, being the only material available.

“One tiny child provided for me their symbol. He was about three years old and he sat on the ground away from the others. He ms in that position when I entered and still there several hours later when I left. When I approached he nervously fingered the sand and looked away, only to finally confront me as I knell in front of him. Soon. I left and he remained as before—alone.”

THE COMMITTEE OF RESPONSIBILITY is an American voluntary organization composed of physicians, surgeons, and interested laymen, which has as its mission the saving of war burned Vietnamese children. The members of the committee feel a deep responsibility, as Americans, for the suffering in Vietnam and see it as an elementary act of justice to work for the welfare of the children who are the innocent victims of American power. The committee has invited all Americans to participate in this work.

The committee lists 105 persons as its sponsors and members. Many of the members have a special professional interest in the care of children. Dr. Herbert Needleman, who is the chairman of the committee’s board of directors, is a psychiatrist. He teaches at Temple University Health Sciences Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Albert Sabin, the developer of the oral polio vaccine, is a member, as are Helen B. Taussig, originator of the blue-baby operation, and professor emeritus of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; and Reverend John C. Bennett, president of the Union Theological Seminary in New York.

Others of the members are simply concerned citizens. Among them are Mrs. Martin Luther King, wife of the civil rights leader, and the noted author Martha Gellhorn.

The Committee of Responsibility plans to make facilities available for the treatment and rehabilitation of war burned Vietnamese children in the United States. In this effort the committee hopes to enlist the aid of physicians, particularly plastic and general surgeons, secure hospital beds and obtain community support for temporary foster home care.

The aim of the committee is to provide plastic surgery and prosthetics treatment not available in Vietnam to children who have been badly burned and disfigured by napalm or who have been injured and lost limbs in the fighting. Six or seven first-class hospitals in Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Los Angeles have indicated willingness to provide facilities. In addition, the committee hopes to raise three million dollars for treatment of the children.

In order to make possible the transportation of war burned Vietnamese children to treatment centers in the United States, the Committee of Responsibility is attempting to enlist the aid of voluntary and government agencies in Vietnam and the United States, obtain U.S. consent for the entry of the Vietnamese children into this country, and secure space in U.S. government aircraft.

The committee hopes for permission to fly the children here on military aircraft, but if this permission is not granted, they will pay for commercial air transportation.

The committee intends to bring children in special groups selected from specific areas in Vietnam to minimize any emotional problems caused by coming to a strange country. Each group will be accompanied by a responsible Vietnamese adult, and each group will remain together throughout treatment.

They make no distinction between children wounded by one side or another. Children will be selected solely on the basis of medical need. “We are not here to establish who is guilty,” Dr. Sabin said, “we’re here to repair the damage.”

The committee is appealing directly to the American people for funds and support. Requests for information and contributions should be sent to:

THE COMMITTEE OF RESPONSIBILITY

777 United Nations Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017

Color photographs by David McLanahan.

Black & White photography courtesy Terre des Hommes.

NO AMERICAN can read this article by Mr. William Pepper and not be horrified by the atrocides that are daily committed in our name.

The war in Vietnam has reached its ultimate and most barbarous stage, with the massiveness of American firepower being brought to bear in rural areas occupied largely by women and children.

The statistics are monstrous. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese children have been terribly burned by American napalm and are receiving scandalously inadequate treatment. Many are gradually dying. A quarter of a million children are already dead in this wasteful war, and another three-quarters of a million have been wounded or maimed since 1961.

This destruction of children is not one of those sad but inescapable accidents of war. It is a direct and necessary result of the Johnson Administration’s policy of unrestricted bombing of the Vietnamese countryside.

This is a policy that, in the face of evidence presented here, must be halted and halted immediately.

There are certain issues beyond political considerations. The killing of children is one of them.

It is possible to receive RAMPARTS Magazine each month by writing to 301 Broadway, San Francisco 94133, California. Introductory rates are $2.67 for six months or $5.00 for one year.

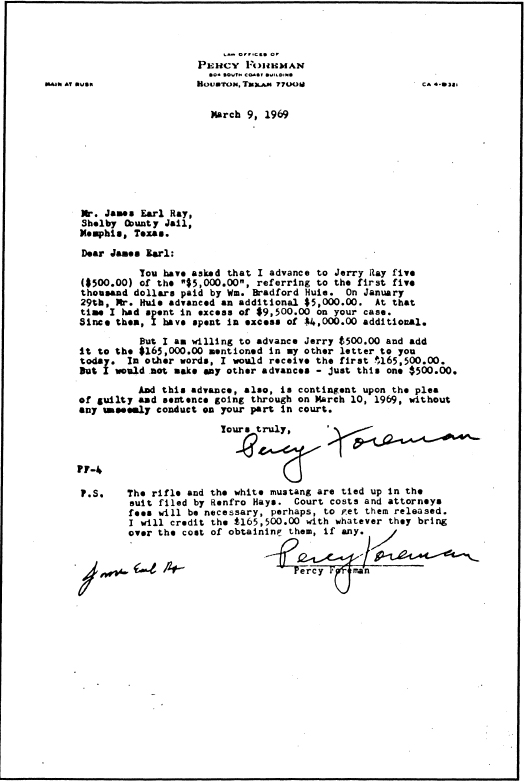

The Letter From Attorney Foreman Agreeing to Pay $500 to James Earl Ray if Ray agrees to Take a Plea

Fee arrangement between Percy Foreman and James Earl Ray which was contingent upon a guilty plea.

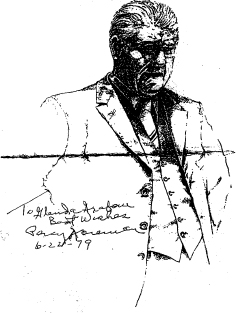

The signed drawing Attorney Foreman gave to Glenda Grabow

27. Sketch of Percy Foreman which he autographed and gave to Glenda Grabow in 1979.

(Artist: Robert McSorley)

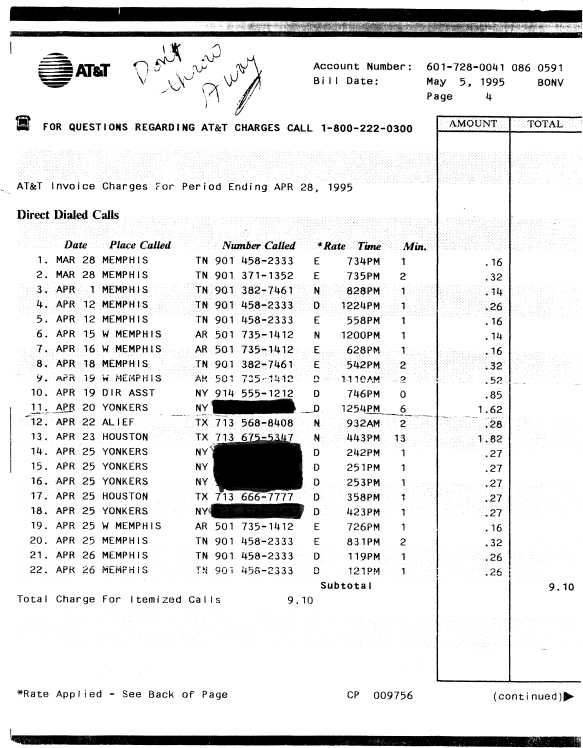

Glenda Grabow’s Telephone Bill

Deposition of Lenny Curtis

The Statement of and Telephone Conversation with Nathan Whitlock

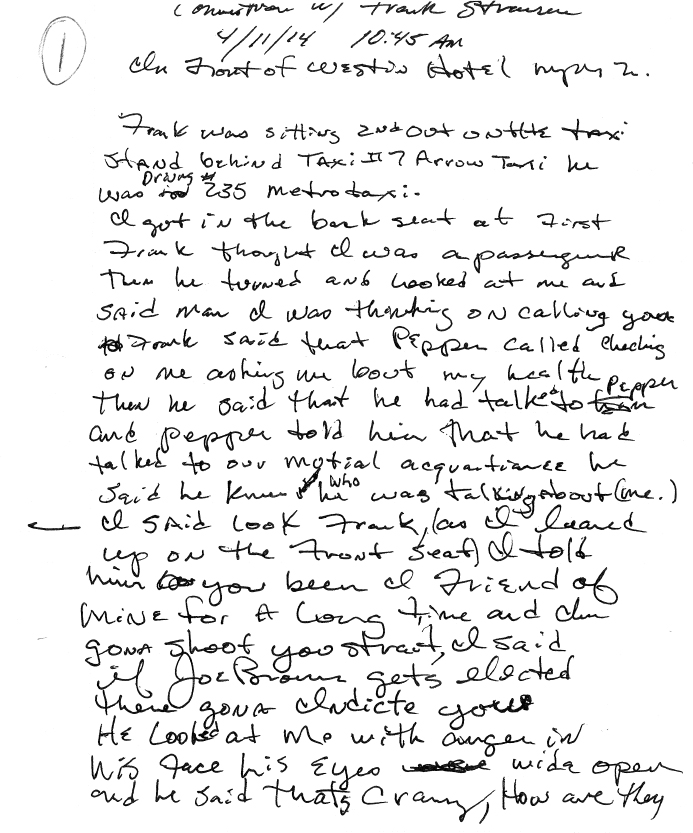

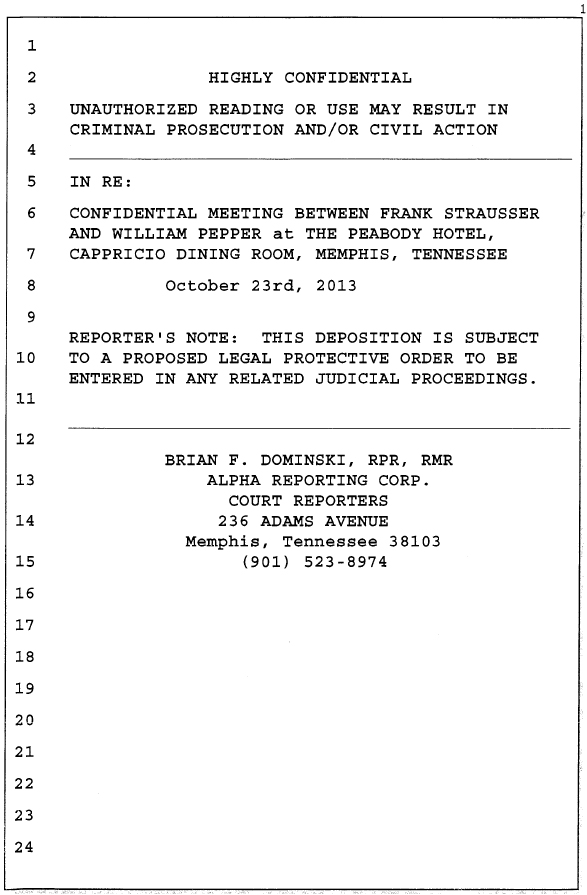

The Interview with Frank Strausser

Deposition of Ron Tyler Adkins

Photographs of Clyde Tolson with Members and Friends of the Adkins Family

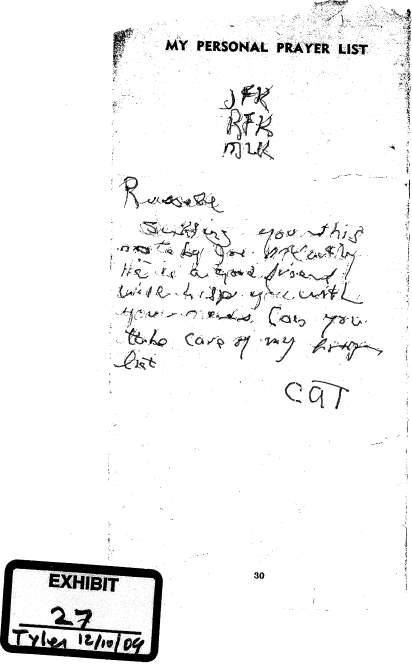

The “Prayer List” of J. Edgar Hoover

Transatlantic Cruise Documents

Photographs of the Alleged Destruction of the Murder Weapon

Deposition of Johnton Shelby

Request for and Opinion of Dr. Cyril Wecht