Sri Lanka’s past is as long as it is varied, with a recorded history stretching back many centuries before the birth of Christ. This is one of the world’s oldest Buddhist strongholds, but also a cosmopolitan melting pot of assorted Asian and European adventurers, traders and settlers, many of whom have left a lasting mark on the island’s religion, culture and cuisines.

Prehistory

Early archaeological evidence of human settlement in Sri Lanka remains slight. The first people to arrive on the island were the Veddahs, an aboriginal hunter-gatherer people thought to be related to the aboriginal peoples of Australia, Malaysia and the Nicobar Islands. They are believed to have arrived in Sri Lanka by around 16,000BC, or possibly much earlier, and survive in isolated pockets in the east of the island in ever-diminishing numbers.

Starting around the 5th century BC, waves of settlers began to arrive in Sri Lanka from northern India. The first arrivals are thought to have come from modern Gujarat, and were followed by further immigrants from Orissa and Bengal. These people, the ancestors of the modern Sinhalese, initially settled on the west coast and gradually pushed inland towards the centre of the northern plains where, in around 377BC, they established the settlement of Anuradhapura. This was Sri Lanka’s first great city and remained the focus of the island’s history for almost 1,500 years.

The Anuradhapura period

The first major landmark in the development of Anuradhapura was the arrival of Buddhism in 246BC, brought to the island by Mahinda, the son of the great Indian Buddhist emperor Asoka. Mahinda quickly converted the Sinhalese king, Devanampiya Tissa, who embraced the new faith enthusiastically. Buddhism provided the Sinhalese with an important sense of national identity, and Anuradhapura soon developed a markedly religious emphasis with the establishment of the great Mahavihara monastery and other Buddhist institutions.

Soon after Devanampiya Tissa’s death, however, Anuradhapura suffered the first of the invasions by Tamils from south India which were to prove a recurrent feature of its entire history. The Tamil general Elara ruled for 44 years before the famous warrior-king Dutugemunu succeeded in ousting the Tamils, uniting the entire island under Sinhalese rule for the first time.

Ruvanvalisaya stupa at Anuradhapura

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The subsequent history of Anuradhapura repeated the theme thus established, with periods of relative stability interspersed with chaotic intervals during which Tamil invaders and Sinhalese infighting threw the island into disarray. In AD473, for example, the notorious Kassapa murdered his father, King Dhatusena, and briefly established a rival capital at Sigiriya. Despite these periodic upheavals, Anuradhapura developed into one of the great cities of its age. Huge tracts of the arid surrounding plains were irrigated and vast reservoirs were built (for more information, click here), while the city’s great monasteries served as bastions of the Buddhist faith and learning. During the 9th and 10th centuries, however, repeated Tamil invasions slowly brought Anuradhapura to its knees, until in 993 the army of the Chola king Rajaraja sacked the city, an event from which it never recovered.

Polonnaruwa period

Having reduced Anuradhapura to rubble, the Cholas established a new capital at the city of Polonnaruwa. The site had the great strategic advantage of being further from India, and thus less vulnerable to foreign interference, and the Cholas ruled there for 75 years until they were toppled by another great Sinhalese warrior-king, Vijayabahu. Vijayabahu’s reconquest of Polonnaruwa ushered in a final golden age of Sinhalese culture in the north. His successor, Parakramabahu, transformed the city into one of the finest of its age, and a rival to the abandoned Anuradhapura. Once again, however, Tamil invaders were to prove the Sinhalese capital’s undoing. In 1212 a new wave of Pandyan invaders arrived, and in 1215 the infamous Magha seized control of Polonnaruwa. His chaotic reign of terror left the city crippled, the monasteries shattered and the great irrigation systems of the north in chronic disrepair, signalling the end of the great early Sinhalese civilisations of northern Sri Lanka.

Buddha at Polonnaruwa – a golden age of Sinhalese culture

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Sinhalese decline and the rise of Jaffna

As Polonnaruwa crumbled, so the Sinhalese nobility gradually migrated south towards the relative safety of the Hill Country, establishing a series of transient capitals whose kings enjoyed increasingly limited control over the island as a whole. Over the next two centuries the island’s great Buddhist institutions collapsed, whilst Tamil Hindu influence began to permeate the island’s culture and religion. At the same time, yet another wave of Tamil invaders established a vibrant new kingdom centred on the city of Jaffna, at the northernmost point of the island, from where they gradually pushed south and east, establishing the Tamil–Sinhalese cultural divide which endures to this day.

The Portuguese

By the beginning of the 16th century, the remnants of the Sinhalese aristocracy had established two major rival centres of power: one in the hills at Kandy, and another near the coast at Kotte, near present-day Colombo. It was the Kingdom of Kotte which was the first to experience the depredations of a new and more exotic wave of invaders, the Portuguese. The Portuguese arrived in 1505 in search of spices, and soon established a fort at Colombo (the origin of the modern city), from where they engaged in periodic skirmishes with Kotte. Although the Sinhalese were initially able to resist Portuguese attacks on land, they had no response to the Europeans’ sea power. The Portuguese gradually spread out along the coast, annexing the declining Kingdom of Jaffna in 1619 and fighting their way around the seaboard until they had established control over much of the island’s lowlands, taking over the Sinhalese king’s monopoly on the sale of elephants, as well as the lucrative trade in spices such as pepper and betel nut. The Portuguese invasion was accompanied by a fervent campaign of missionary activity, with considerable swathes of the coastal population converted to Catholicism and numerous temples destroyed. This explains the origin of the numerous Sri Lankan de Silvas, Pereiras and Fernandos who inhabit the island to this day.

The Kandyan Kingdom and the Dutch

One final bastion of Sinhalese power remained, however: the Kingdom of Kandy, buried deep in the impenetrable hills of the interior. The Portuguese were unable to subdue Kandy, despite repeated attempts – while the Kandyans, in turn, launched offensives against the Portuguese, though their lack of sea power prevented them from permanently evicting the European interlopers.

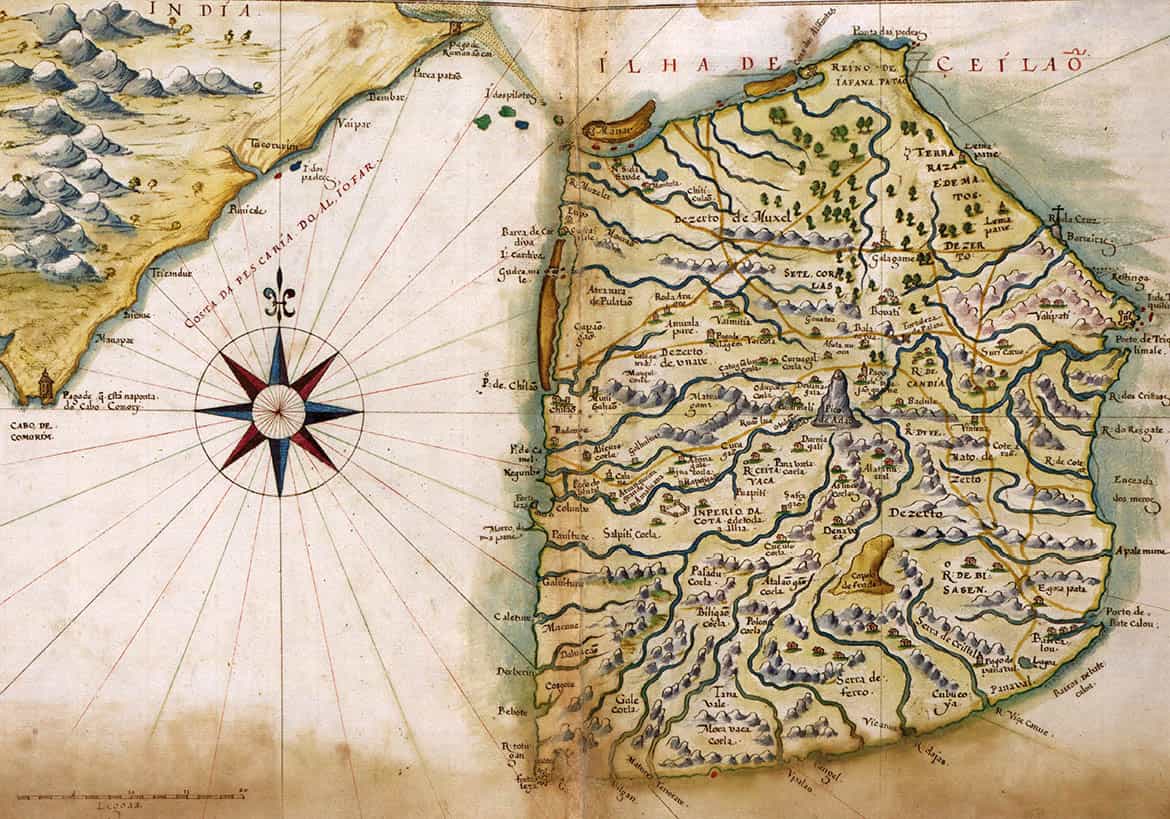

Map of Ceylon, 1630

Getty Images

It was the hope of driving the Portuguese out of Sri Lanka once and for all that led the Kandyans into an unlikely alliance with another European power, the Dutch, who had increasingly begun to covet the island’s rich natural resources.

Between 1638 and 1658 the Dutch systematically attacked and overran Portuguese coastal strongholds, though they showed no signs of handing any of these conquered territories back to the Kandyans. Having established their mastery over much of the island, the pragmatic Dutch set about promoting trade and systematically exploiting the island’s commercial possibilities. They also made modest efforts to promote their Calvinist Protestant faith at the expense of Catholicism, which they declared illegal.

The British

It was, however, the third and final of the colonial powers to occupy Sri Lanka, the British, who were to exercise the most lasting influence on the island. Like the Dutch, the British (already firmly established in neighbouring India) had had their eyes on Sri Lanka – particularly the strategic deep-water harbour at Trincomalee – for some years. Unlike the Dutch, they were able to take possession of the island with a minimum of military fuss thanks to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. When the Netherlands fell to the French in 1794, the British stepped in to ‘protect’ the Dutch colony from French interference. The Dutch mounted only token resistance, and British possession of the island was formally ratified by the Treaty of Amiens in 1802.

Like the Dutch, British policy in Sri Lanka was largely aimed at maximising the island’s commercial potential and their legacies – most notably the country’s tea industry, its railways, and the English language itself – remain essential elements of the modern island’s commercial and cultural landscape. The British also finally succeeded in taking possession of the recalcitrant Kandyan Kingdom, thanks to the efforts of the arch colonial schemer Sir John D’Oyly, who succeeded in turning the kingdom’s Sinhalese nobles against their Tamil king. In 1815, after three centuries of spirited and often bloody resistance, the Kandyans meekly surrendered, finally extinguishing the last bastion of independent native rule in the island.

Towards independence

The later part of the 19th century was a period of intense soul-searching for the Sinhalese. Faced with an occupying and unshiftable European power and the constantly encroaching influence of missionary Christianity, the islanders began to re-evaluate their traditional religious and cultural beliefs, creating a vigorous Buddhist revivalist movement. As the 20th century dawned, this movement became increasingly politicised, leading to the foundation of the Ceylon National Congress in 1919. The British gradually began to make concessions, and in 1931 a new constitution gave the island’s political leaders the first opportunity to exercise real (though still limited) political power, as well as granting the islanders universal suffrage.

A European in a rickshaw, 1933

Mary Evans Picture Library

During World War II Sri Lanka became a strategically vital base for British operations in Asia following the fall of Indonesia, Burma and Singapore to the Japanese. It even attracted the attentions of the Japanese air force, who launched raids against Colombo and Trincomalee. Following the war, the enfeebled British Empire gave up its colonial possessions, and Sri Lanka finally achieved independence on 6 February, 1948.

Independence

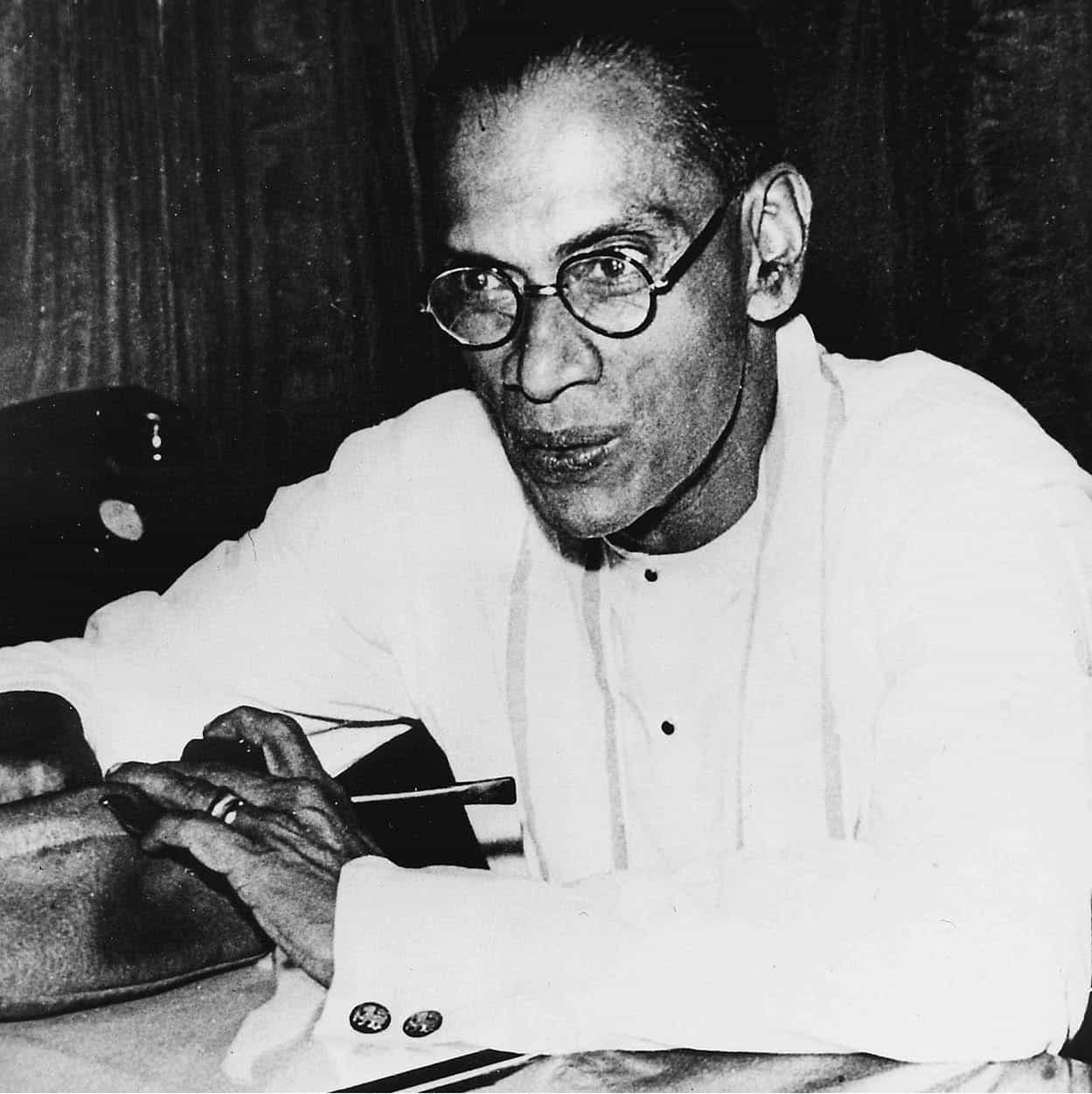

Power was handed to the United National Party (UNP), a generally conservative party dominated by the English-educated leaders such as the Senanayake family, who had risen to prominence under the British. The UNP ruled until 1956, when they were ousted by the more populist and nationalist Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), led by the charismatic S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. These two parties have alternated in power ever since – with the Senanayake and Bandaranaike families (or their close relatives) providing most of the island’s leaders up until recent times. This has particularly been the case with the SLFP. When S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was assassinated by a Buddhist monk in 1959, leadership of the party passed quickly to his widow, Srimavo, who thus became the world’s first ever female prime minister. Their daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga would later serve as both prime minister and president, a dynastic family sequence to rival the Nehrus in India, and one which gained the SLFP the nickname of the ‘Sri Lanka Family Party’.

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike

Alamy

The early years of Independence were kind to Sri Lanka, but during the 1950s and 1960s increasing economic difficulties and falling living standards led to widespread disenchantment, culminating in the 1971 armed rebellion staged by the JVP, a quasi-Marxist, student-led organisation with a pronounced nationalistic, anti-Tamil stance. The insurrection was put down with considerable loss of life, but anti-Tamil rhetoric became a feature of national political life. A controversial sequence of legislative changes drove the Tamils into the margins of the island’s commercial and political life. A new generation of militant Tamil organisations sprang up in the north of the island – including the Tamil Tigers, or LTTE – and the number of confrontations between them and the Sri Lankan police and army began to increase.

Civil war

Anti-Tamil sentiment reached a peak in 1983 when, following an LTTE massacre of an army patrol in the north, Sinhalese mobs launched an orgy of violence against Tamils across the island, killing as many as 2,000 people. Thousands of Tamils fled to the north or departed overseas, while corresponding numbers of Sinhalese came south. By 1985 the conflict had developed into an all-out civil war between the Sinhalese-dominated Sri Lankan Army (SLA) and the guerrilla forces of the LTTE.

In 1987 the Indian government, under increasing pressure from its own enormous Tamil population, intervened in the conflict by despatching the hugely controversial Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF) to the island to enforce a ceasefire, although it rapidly became embroiled in heavy fighting with the Tamils it had allegedly come to protect. Meanwhile, in 1987, a second JVP rebellion broke out in the south, reducing the entire island to a state of near anarchy.

The JVP rebellion was once again put down with brutal force, while in 1990 the IPFK, facing mounting casualties, left the island, to the relief of both Tamils and Sinhalese. Heavy fighting continued throughout the north and east between the LTTE and SLA, while repeated LTTE suicide-bomber attacks against Colombo and other southern targets claimed thousands of civilian casualties. A ceasefire was finally agreed in 2002, and the island enjoyed a few years of relative peace, although the situation steadily deteriorated, exacerbated by the catastrophic effects of the Asian tsunami, which struck the island on 26 December 2004, killing some 38,000 people and reducing many settlements around the coast to rubble.

Peace at last?

The military stalemate was finally broken in 2005, with the election as president of Mahinda Rajapakse. In 2007, Rajapakse launched a decisive offensive against the LTTE. Over the next 18 months the SLA systematically drove the Tigers out of their strongholds in the east and then north of the island, finally announcing victory (along with the killing of the LTTE’s legendary leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran) in May 2008. The triumph was achieved at a terrible human and economic cost, alongside accusations of widespread atrocities and war crimes. Rajapakse was elected for a second five-year term in 2010, although human-rights issues continue to cloud his reputation, ranging from the treatment of Tamil civilians through to independent journalists and rival politicians. The 2015 election, regarded as the most significant for decades, ended the dynastic rule of Rajapakse. The newly elected president, Maithripala Sirisena, pledged to bring in constitutional reforms to reduce presidential power and to return the country to a parliamentary system governed by a Prime Minister. However, this led to a constitutional crisis when, in October 2018, Maithripala Sirisena assigned former president Mahinda Rajapaksa as prime minister before dismissing the incumbent Ranil Wickremesinghe, resulting in two joint prime ministers. The United National Party (UPN) declared this illegal and unconstitutional and refused to accept the appointment of Maithripala Sirisena. This instability was projected worldwide causing economic issues within the country. The crisis was resolved in December 2018, with the involvement of the Supreme Court leading to President Sirisena agreeing to appoint Wickramasinghe as sole prime minister, but not without leaving lasting damage.