5

PRANAYAMA

Pranayama is a Sanskrit word formed by two words. Prana means a subtle life-force which gives energy to the mind and body, and ayama signifies the voluntary effort to control and direct this prana.

Pranayama is essentially a process by which prana is controlled by regulating the breathing voluntarily. It involves a temporary pause or interval in the movement of breath.

The basic movements of pranayama are rechak (exhalation), purak (inhalation), and kumbhak (retention of the breath).

Having instructed us in the mastery of the meditation posture (asana), by being steadily and firmly seated with the mind or attention flowing in one direction, Patanjali now proceeds with pranayama, which he deals with in five sutras (49–53, Sadhana Pada).

Having established a firm, steady posture, one then regulates the life-force (prana) by natural voluntary suspension of the breath after inhalation and exhalation — this is pranayama.

Yoga Sutras 2:49

In this sutra he is saying, ‘Exhale and retain the breath.’ This does not mean exhale, inhale and hold the breath, but rather that if you breathe out and then refuse to inhale again, you will very soon experience what prana is. It jumps quickly into activity when you are forced to inhale another breath. What makes you take the next breath after holding it out for so long is prana.

Please try it, for no definition can ever show you prana as clearly as one moment's experience. If you want to know what total absorption of the mind is, exhale and suspend the breathing. You will find that during that period, you will think of nothing except your breath. It is not possible to think of anything else at all. A few seconds will seem like half an hour.

The Hatha yogis’ explanation of this is that it is the breath (or the movement of prana) that enables your mind to think. If this is suspended, then the mind loses its fuel, and so it is no longer distracted, it becomes quiet.

During deep meditation the breath naturally becomes suspended for a short period of time, and it is this interval that constitutes pranayama. To the meditator in such deep meditation, there is no sense of time; the mind is still, and in that deep peace, there is joy or bliss.

The variations in pranayama are external, internal or suspended. The interval is regulated by place, duration and number, and becomes progressively prolonged and subtle.

Yoga Sutras 2:50

In this sutra Patanjali describes three types of pranayama on the basis of the nature of the interval that causes a temporary suspension of breath.

• a pause after a very slow and prolonged exhalation (bahya kumbhaka — external breath retention)

• a pause after a deep, prolonged inhalation (abhyantara kumbhaka — internal breath retention)

• a prolonged pause in between the inhalation and exhalation

In this technique, he says the interval is regulated by place, duration and number.

• Place refers to where the breath is held (external, internal or suspended).

• Duration refers to the duration of the breath retention.

• Number means the ratio between inhalation, retention and exhalation of the breath.

The fourth type of pranayama is the spontaneous suspension of the breath, that occurs while concentrating on something external or internal.

Yoga Sutras 2:51

This spontaneous suspension of the breath (known as keval kumbhaka) is experienced by the practitioner at any time without any effort. It comes automatically after prolonged practice of pranayama.

The attainment of pranayama removes mental darkness and ignorance, which veils the inner light of the soul … And the mind attains the power to concentrate.

Yoga Sutras 2:52–3

The benefits of pranayama are given in these two sutras. If you practise pranayama efficiently and effectively, the veil of dark ignorance that covers the inner light is removed. Pranayama aids contemplation and removes distraction from the mind, so that it becomes easy to concentrate and meditate.

Throughout the Yoga Sutras, there is a simple but very important message for us to remember: ‘Practise yoga in order that these obstacles [of the mind] may be removed.’ When the obstacles are removed, then the Self (Seer) rests in its own true nature and life becomes enlightened.

PRANA, THE VITAL ENERGY OF THE UNIVERSE

When there is prana in the body, it is called life; when it leaves the body, it results in death. So one should practise pranayama.

Yogi Svatmarama, Hatha Yoga Pradipika 2:3

The Sanskrit word prana translates as ‘first unit of life-force’. There are many terms used for it, including ‘vital energy’, ‘breath of life’ and ‘life-force’. Paramhansa Yogananda translated it as ‘lifetrons’, in essence, condensed thoughts of God or substance of the astral world.

Paramhansa Yogananda developed a God-inspired system of 39 ‘energization exercises’ to recharge the brain and body with cosmic energy (prana) directly. Those devotees who follow his path of Kriya Yoga and practise these recharging exercises know the secret of recharging and energizing the body at will, at any time or place, with prana, the electric life-current given to us by God.

Prana is the link between the astral and physical bodies. When this link is broken or cut off, then the astral body separates from the physical body, and what we call death takes place. The prana departs from the physical body and is withdrawn into the astral body. Similarly, if a car battery is disconnected from a motor car engine, or any electrical appliance is disconnected from the electric power supply, the motor car or the electrical appliance are of no use, they are dead without the electric current flowing through them.

Everything in the human, animal and plant kingdoms, is dependent on the air it breathes to live. Life, prana and breath are intimately connected. There is not one life form that can survive, or even move, without the current of energy called prana.

When the breath [prana] is restless, the mind also becomes unsteady, but when the breath is still, so is the activity of the mind. Then a yogi attains a complete motionless state of consciousness (chitta). One should therefore restrain one's breath.

Yogi Svatmarama, Hatha Yoga Pradipika 2:2

Prana is intimately related to the mind and mental processes; one cannot move without the other also moving. When there is turbulence in the mind, the breath becomes restless and vice versa — the breath (movement of prana) also affects the mind and its mental processes.

We need only to be aware of emotions such as anger, fear, hatred and jealousy to feel what effect it has on our breathing. When we become angry or emotionally upset, our breathing is markedly changed in its rate and depth. For example, when we become angry, the breath becomes faster and we lose control over it and over our mind. Anger agitates and shatters the whole nervous system, and can also lead to hatred, which is even worse; for when the heart is attuned to hate it is impossible to feel attunement with God, who is love.

The emotions and the mental processes are related to the nervous system and through it they change our breathing. That is why it is important to develop positive attitudes and positive thoughts, and to change or overcome unwanted negative or destructive tendencies and behaviours. How? By developing the virtues we associate with divine qualities: love, inner joy, compassion, selflessness, kindness, generosity, loyalty, gentleness, forgiveness, peacefulness, calmness and contentment.

When these virtues are naturally and spontaneously expressed, then the energy naturally and continuously flows in abundance. The prana in an upward flow permeates the whole body, elevating the consciousness. Conversely, if we become negative in our thoughts, attitudes and behaviour or suppress our natural feelings, the pranic flow of energy sinks downward, the energy becomes concentrated in the lower part of the body. The body and mind become depressed and the breath unstable.

The practice of pranayama helps in transforming the total personality by clearing mental obstructions, purifying the subtle channels (nadis) through which pranas flow, awakening dormant vital forces in the body, focusing the attention, developing concentration and improving overall health and vitality.

By the proper and careful practice of pranayama one attains optimum health, a peaceful, steady mind and a firm and lustrous body free from disease.

Yogi Svatmarama, Hatha Yoga Pradipika 2:16–18

Pranayama aims primarily at controlling the mind and suspending the mental activity and ego-consciousness (the seat of vrittis — see below) in order to bring about a still mind. With the mind still and the breathing calm, the inner light of the true Self shines radiantly. The light of the Self is always pure, even though it is tinted by the coloured filters of the mind. When the coloured filters are removed, there is only one pure light, the true Self.

VRITTIS — INSTINCTS, URGES AND DESIRES

Vrittis translates as ‘fluctuations’, ‘modifications of the mind’, ‘waves’, ‘thought waves’, ‘mental whirlpool’.

The mind which exists in the astral body is called antahkarana (inner instrument). It contains four main elements:

• manas (mind) — thinking, willing, doubting, recording faculty of the mind

• buddhi (intellect) — discriminating and decision-making faculty of the mind, and intuitive wisdom

• ahamkara (ego) — self-arrogating part of the mind which sees itself as separate from God and others; identifying faculty of the mind

• chitta (subconscious) — the storehouse of past experiences; memory; ‘mind-stuff’, mind-field

The chitta or ‘mind-stuff’ is a composite of three primordial energies in creation. These three energies or attributes of nature (prakriti), are called gunas (qualities):

• sattva — quality of truth, purity, light

• rajas — quality of passion, energy, desire

• tamas — quality of ignorance, inertia, darkness

Like three intertwined cords in a rope the gunas pulsate in the mind, one more vibrant or dormant than the other at a given time. They interact in various degrees on each other giving us the experience of happiness and fulfilment, pleasure and pain, and lack of energy and indifference.

When the mind is of a sattvic nature it performs good actions, it is virtuous, peaceful, calm, joyful and selfless.

When the mind is of a rajasic nature it is egotistical, absorbed in worldly and selfish interests. It is restless with desires.

When the mind is of a tamasic nature it is careless, ignorant, lethargic, negative, depressive, dull and selfish.

The chitta is very much like a lake on which waves rise and fall. These waves are the innumerable thoughts that give existence to the mind. Without these ‘thought waves’ (vrittis) the mind cannot survive, it has no existence. The mind clings to that with which it identifies, thinking that its security comes from there. It thinks, feels and directs the senses to act accordingly. The ‘I’ (ahamkara) gives the motive power to the instincts in the mind, which generates desires in relationship to objects through an outward projection, and registers them inwardly as memory, by experience for later reference.

The innumerable vrittis that are rising and falling in each moment within the mind-field (chitta) can be divided into five main categories, called kleshas (afflictions).

Kleshas are of two kinds:

• klishta (afflicted, painful, distressing)

• aklishta (not afflicted; non-painful, pleasing)

These are the five main causes of suffering in life as given by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras, 2:3–9.

1 ignorance (avidya)

2 I-am-ness (asmita)

3 attraction (raga)

4 aversion (dvesha)

5 fear of death/clinging to life (abhinivesha)

First there is ignorance (avidya), the source of all the other obstacles. The meaning of ignorance here is to ignore the truth of our spiritual identity — a lack of inner awareness of the eternal, blissful, conscious, divine Self. Ignorance creates delusion, which covers the knowledge of the Self. Without experiencing our own true eternal nature, we cannot realize that this same divine Self exists in all creatures. In ignorance we create a sense of separateness from each other and from God.

I-am-ness or ego (asmita) is identification of the self with the body, mind and senses. It is forgetfulness of our true divine nature.

In this forgetfulness we experience ourselves as finite, limited and temporal.

Attraction (raga) is the restless pursuit of pleasure; attraction to the objects of the senses. It is also confusion of wants and needs.

Aversion (dvesha) is a dislike or avoidance of that which brings unhappiness and suffering.

Patanjali's fifth klesha, fear of death (abhinivesha), is the tenacious clinging to life, not wanting to let go of the ego. It is resistance to change.

Clinging to life is the habit of dependence on objective sources for enjoyment and happiness, and fear of losing them. The greatest fear is death, fearing that we will cease to exist and lose our identity.

Patanjali gives us the remedy for overcoming these five afflictions (kleshas). (Yoga Sutras 2:10–11). He informs us that these afflictions may be subtle or gross. To reduce or eliminate the subtle afflictions one has to reverse the energy of the thought responsible for each affliction, back to its source or cause in the ego, and purify it with its own true opposite. For example, if the feeling of attraction or repulsion enters the mind, then substitute it with contentment or acceptance.

The gross, active and outward expressions of the five afflictions can be silenced through meditation.

Another remedy Patanjali gives to us, (Yoga Sutras 2:26) is the unwavering practice of uninterrupted awareness, discriminating between what is real and what is unreal. This is the means to remove ignorance.

Patanjali then tells us (Yoga Sutras 2:27–28) that the impurities of the mind are diminished and that we can attain the highest stage of enlightenment through the dedicated practice of the seven limbs of yoga (samadhi, being the eighth limb).

Self-realization is attained by discrimination, dispassion, determination, unbroken awareness, whole-hearted dedication to the practice of yoga and meditation. The mind has to be purified and made one-pointed. It takes patience, perseverance, and a burning aspiration for truth to succeed on the spiritual path.

THE FIVE LIFE-FORCES OF THE BODY

The movements of prana are not only those which enter this body through the vehicle of the breath. There are movements of prana also within one's own body. These pranas are called vayus (vital airs); they are the intelligent life-forces which are manifested in the astral body and function through the five subsidiary nerve centres in the brain and spinal cord.

THE FIVE MAJOR VAYUS

• Udana vayu functions in the body above the larynx (throat) and the top of the head. It controls the automatic functions of the cephalic divisions of the autonomic nervous system. It controls speech, the sense of balance, memory and intellect. Udana has an upward movement — it carries kundalini to the sahasrara, and separates the astral body from the physical body at the time of death. Udana is a pale white colour.

• Prana vayu functions in the region between the larynx and the base of the heart. It uses the autonomic nervous system controlling speech, the respiratory muscles, blood circulation and body temperature. Prana is the colour of blood, or a rose pink like that of a coral.

• Samana vayu functions between the heart and the navel region, maintaining a balance between apana and vayu. Through the sympathetic part of the autonomic system, it controls all the metabolic activity involved in digestion. Samana is a colour somewhere between that of milk and crystal, which shines.

• Apana vayu functions in the region from the navel to the feet. It has a downward movement normally, but carries the kundalini shakti upwards in sushumna to unite with prana. Apana controls the functions of the kidneys, excretory system, colon, rectum and sex organs through the autonomic system. Apana is a colour between white and red.

• Vyana vayu permeates throughout the whole body and is the aura around the body. It helps the other vayus to function properly. It controls both the voluntary and involuntary movements of the muscles and joints. It keeps the whole body upright by generating unconscious reflexes along the spine. In addition to this, it controls the physical nerves and the subtle astral nerves (nadis). Vyana is the colour of a ray of light.

THE FIVE MINOR PRANAS

• Naga controls the function of belching and hiccoughing. It also gives rise to consciousness.

• Kurma controls the function of opening the eyelids and causes vision.

• Karikara controls sneezing and induces hunger and thirst.

• Devadatha controls yawning.

• Dhananjaya causes the decomposition of the body after death.

GUIDELINES FOR THE PRACTICE OF PRANAYAMA

Place

Select a clean, warm, airy place to practise in, a room where you can sit quietly without being disturbed. If you can sit outside, then make sure that you are warm, away from pollution, noise and distractions.

Time

Pranayama is best commenced in spring (especially after doing a ‘spring cleansing’ such as shankhaprakshalana). Pranayma can be practised throughout the year, but do not practise in the heat of the sun or when the body is cold or ill. Practise early in the day, preferably before sunrise, when pollution is at its lowest concentration. You can also practise after sunset, when the air is cool.

Posture

Sit on a folded blanket or cushion in a suitable meditative asana for pranayama, such as padmasana (lotus pose), siddhasana (accomplished pose), swastikasana (auspicious pose) or vajrasana (thunderbolt pose) (see Chapter 8). The posture you choose to sit in should allow you to keep your back erect from the base of the spine to the neck and you should be able to sit comfortably and relaxed with your eyes closed.

Precautions

Do not practise asanas immediately after pranayama. Relax after strenuous asana practise before practising pranayama.

Do not practise pranayama immediately after meals; allow at least four hours after eating. If you are hungry, just eat a small snack or drink. You can eat half an hour after pranayama.

When practising pranayama do not force, strain or breathe in jerky movements. Do not struggle to restrain the breath after inhalation or exhalation. If you feel any adverse symptoms, then stop your practice immediately and rest.

If you have practised pranayama incorrectly you can do viparita karani mudra (see chapter 4), and hold for as long as comfortable, breathing normally. If you feel that too much heat has been generated in the body due to pranayama, then stop your practice, apply vegetable oil to the body, head and soles of the feet by massage. A little later, take a hot bath and then lie in shavasana (yoga relaxation pose) for 20 minutes to relax.

Women should avoid kapalabhati and bhastrika (bellows breath) during pregnancy. A long retention of the breath should also be avoided after full exhalation (bahya kumbhaka) with uddiyana bandha. However, the following pranayamas can be practised, and will give benefit: nadi shuddhi (alternate nostril breathing), surya bhedana, chandra bhedana, viloma pranayama and ujjayi pranayama.

It is safe to practise pranayama during the menstrual period, but avoid uddiyana bandha (abdominal contraction).

PREPARATION

Before commencing pranayama practice, cleanse the nostrils with the jala neti technique (see Chapter 4); this also helps to equalize the flow of breath in each nostril. One can also cleanse the nostrils and strengthen the mucous membrane with the technique of sutra neti (see chapter 4).

When you have cleansed the nostrils and made sure that all the water has been drained from the nasal passages, it is good to do a few preliminary warm-up exercises to open the chest and lungs to facilitate good breathing. The following is a useful exercise for the lungs.

1 Stand with your feet together with your arms down by your sides. Slowly take a long, deep inhalation as you slowly raise your arms above your head. Stretch right up onto your toes and pull your shoulders back as you stretch your arms up above your head. Then as you exhale, slowly lower your arms back down to your sides. Repeat five times.

2 Stand with the feet hip-width apart and inhale as you raise your arms above your head. Keep your arms straight, but with your hands and wrists relaxed. Exhale as you rotate your arms forward in a wide circle. Imagine yourself as a windmill, and your arms as the turning sails. Breathe deeply and slowly to open the lobes of the lungs. As you raise your arms, inhale and as you lower them, exhale. Practise the forward motion of the arms for five rounds then change direction and rotate them back, pulling your shoulders back as you do so.

You can also practise a few yoga postures that help to open the chest and expand the lungs, such as ustrasana (camel pose) chakrasana (wheel pose – see chapter 4) and matsyasana (fish pose). These all help to increase the flexibility of the rib cage and the expansion of the lungs.

Ustrasana (camel pose)

Method:

1 Kneel with your thighs at a right angle to the floor. Keep the knees and feet together, and your trunk upright. Place your hands on your hips. Inhale, contract your buttock muscles and raise your hips and trunk.

2 Exhale and arch your back, pushing the pelvis and lumbar region of the spine forwards. Keep your shoulders back and extend your neck.

3 Take each hand back in turn to hold your heels with the palms on the soles, fingers toward the toes. Carefully bend your head back. Hold the pose for ten seconds, gradually increasing to one minute.

4 Inhale. Slowly and carefully raise your trunk up by placing your hands on your hips and contracting your buttocks. Then relax.

Figure 18 Ustrasana (camel pose)

Benefits:

• Opens the chest.

• Gives flexibility to the spine.

• Stimulates digestion.

• Strengthens the lungs and reproductive glands.

Another good posture for preparing the respiration for pranayama is padadirasana (breath balancing pose). Sit in vajrasana, cross your arms and place your hands under your armpits, with the thumbs pointing upwards. With a little pressure, press your fingers against your armpits. Close your eyes and concentrate on the point between the eyebrows. Breathe slowly and rhythmically, with awareness on the breath.

This posture is most beneficial when held for at least ten minutes. It can be practised at any time, even after meals. It keeps both nostrils open, relieving discomfort from blocked nasal passages.

The following breathing exercises are best practised before the pranayama session, after opening the lungs.

Cleansing Breath: Exercise 1

Sit in vajrasana with your hands resting on your knees, palms down. Inhale a complete yogic breath (see pages 197–9) and hold it for a few seconds. Then pucker your lips and exhale vigorously through them in a series of short, sharp exhalations as you slowly lower your trunk and forehead to the floor. Relax, while holding your breath out for a few seconds, then slowly raise your head and trunk back up while slowly breathing in through the nostrils. Practise three times.

This breath is very beneficial for ventilating and cleansing the lungs. It stimulates the cells and gives a good tone to the respiratory organs. It eliminates carbon dioxide from the system.

Cleansing Breath: Exercise 2

Stand with your feet together, arms relaxed by your sides. Take a complete yogic breath, then with your lips puckered, ‘whoosh’ the breath out powerfully as you slowly bend at the knees to bring your fingers to the floor. While crouching down, hold your breath out for a few seconds, then slowly breathe in through your nostrils as you stand up. Your arms and back should be kept straight but relaxed throughout the practice. Repeat up to ten times.

This breath cleanses the system of carbon dioxide very quickly. It stimulates the expansion of the blood vessels and the blood pressure falls.

But beware: it should not be practised by those with heart problems or problems with blood pressure.

Cleansing Breath for the Nasal Passages and Sinuses

1 Sit in a comfortable posture with your spine straight and your body relaxed.

2 Slowly inhale through both nostrils, hold the breath for two or three seconds, then pucker your lips and exhale all the air from your lungs with a series of dynamic exhalations, like a bellows action.

3 Inhale through your left nostril, closing the right nostril with your right thumb, resting your index and second fingers at the point between your eyebrows.

4 Hold your breath for two or three seconds, then close your left nostril with the third finger of your right hand and exhale through your right nostril, with a series of short, sharp exhalations.

5 Now repeat this process, inhaling through the right nostril and then through both nostrils again.

6 Practise this cleansing breath for one week, starting with one round on the first day, two rounds on the second, three on the third day, and so on.

This cleansing breath is an atomising breath that expels any waste matter or toxins from the nasal passages and sinuses. It is very beneficial for those suffering from congestion in the head.

PRANA MUDRA (FOR AWAKENING THE PRANIC ENERGY)

Sit in a comfortable meditative asana, close your eyes and relax your body. Place your hands, palms up, in your lap, with the left hand on top of the right. There are six stages, as follows.

1 Emptying the lungs

Exhale deeply, contracting the abdominal muscles, squeezing as much air out of the lungs as possible. Then perform mulabandha (see chapter 4) with the breath held out.

2 Starting inhalation to manipura chakra

Release mulabandha and inhale through both nostrils slowly and deeply, visualizing the breath as a pure white light ascending within the sushumna nadi. Simultaneously raise both hands so that the palms and fingers are pointing to your navel. As you inhale focus your awareness at the manipura chakra (solar plexus centre) and draw the prana up to it from the muladhara chakra.

3 Inhalation from manipura to anahata chakra

Continue inhaling, moving your hands up with the inhaling breath until they are in front of the heart (anahata chakra), expanding the chest and filling the upper lungs with air.

4 Inhalation from anahata to vishuddhi and ajna chakras

In the last step of this inhalation, continue inhaling, raising your rib cage under your collarbones to fill the upper lobes of your lungs with air. Simultaneously raise your hands so that they pass in front of your throat (vishuddhi) and eyebrow (ajna) chakras. Feel the prana being drawn up through these chakras.

5 Internal breath retention

Retain the breath and keeping your hands at the level of your ears, stretch your arms out to the side, bent at the elbows and with the palms facing upwards. Now concentrate on the crown chakra (sahasrara), visualizing pure white light energy pouring down into you. Feel your entire being radiating with this soothing white light. It surrounds your whole body, then it gradually expands and encompasses the room or area you are in. It continues to expand throughout the whole country, then the whole world, radiating love and peace to all beings. Retain the breath and this feeling for as long as is comfortably possible, without straining the lungs.

6 Exhalation down through the chakras

The exhalation begins in reverse order — exhaling from the top of the lungs first (chest, diaphragm, abdomen). As you exhale, pass your hands simultaneously down in front of the chakras, visualizing the breath as a pure white light descending through the chakras in the sushumna nadi.

At the end of the exhalation concentrate on the muladhara chakra and repeat steps 2–6.

Practise a minimum of five rounds.

This practice recharges and revitalizes the body and brings peace and serenity to the mind.

STIMULATING AND CLEANSING THE LUNG CELLS

This is a very stimulating breathing exercise which activates the air cells in the lungs and invigorates the whole body.

1 Stand with your feet hip-width apart.

2 Inhale with a long, slow, deep breath (complete yogic breath — see pages 197–9) and simultaneously tap all over your chest with your fingertips.

3 Retain the breath and pat all over your chest with the palms of your hands.

4 Pucker your lips and exhale powerfully, blowing or ‘whooshing’ the breath out through your mouth. Extend your arms out in front of you and lean forward with your head down as you exhale.

5 Hold your breath out while leaning forward in the standing position for as long as is comfortable, then slowly inhale through both nostrils as you slowly come back to the upright position.

Caution: If you feel dizzy then discontinue the practice. In the beginning you may do so, but with careful practice you will overcome the dizziness.

SWARA YOGA

The Sanskrit word swara is from the root swar, ‘to sound’. Swara basically means ‘air inhaled through the nostrils’. Swara Yoga is the ancient science of studying the flow of prana, and is also known as Swarodaya and Swara Vijnana.

The Swara yogis of India studying this science experimented and made great detailed correlations between the way the breath flowed and various physiological and psychological states. They produced detailed lists of examples, some of which are represented in the table below. The figures represent the various distances from the nose that the exhalation of air can be felt during a person's different activities and moods. The length of the breath is mentioned in the classical yoga treatise, the Gheranda Samhita. The body of vayu (air) is 96 digits (6 feet) in standard length.

| Normal state | — | 6 digits (4½ inches) |

| During emotion | — | 12 digits (9 inches) |

| During singing | — | 16 digits (12 inches) |

| While eating | — | 20 digits (15 inches) |

| While walking | — | 24 digits (18 inches) |

| During sleeping | — | 30 digits (22 inches) |

| During sexual intercourse | — | 36 digits (27 inches) |

| During physical exercise | — | over 36 digits. |

(Note: One digit equals ¾ inch)

You can measure your own breath by moistening the back of your hand and holding it under your nostrils. As you exhale you will feel the air blowing on to your skin. Then measure the length of your breath from hand to nostrils.

SWARA YOGA AND LONGEVITY

Yogis have stated that a person who breathes shallowly in short, sharp gasps is likely to reduce his or her lifespan, compared with a person who breathes slowly and deeply. So sure were they of this principle that they measured a person's lifespan, not in years but by the number of breaths. They considered that each individual is allocated a fixed number of breaths in their lifetime, with the number varying from person to person. Therefore if a person breathes slowly and deeply, they not only gain more vitality but they also optimize their experience of life.

The ancient yogis who lived in the forests of India, or in secluded hill or mountain regions, had intimate contact with nature all around them. In this natural environment they were able to study the wild animals in great detail. They discovered that animals with a slow breathing rate, such as snakes, crocodiles, elephants and tortoises, have a long lifespan. Conversely, they noticed that animals with a fast breathing rate, such as birds, cats, dogs and rabbits, live only for a few years. It was from this observation that they realized the importance of slow breathing.

It is also interesting to note that the respiration is directly related to the heartbeat. Slow respiration occurs with a slow-beating heart, which is conducive to a long lifespan. For example, a whale's heart beats about 16 times a minute, and an elephant's approximately 25. Both these animals are renowned for their long lifespans. A mouse's heart, on the other hand beats approximately 1,000 times a minute, and it lives a short life.

It is said by the yogis that a normal person breathes 21,000 breaths a day and in comparison to some of his or her friends in the animal kingdom, lives a relatively short life.

There have been, and there still are, many great yogis who have lived or are living very long lives; their vital endurance is remarkably increased by the practice of yoga, pranayama and meditation. Through their yogic practices and attunement with God and the laws of Nature, they have mastery and control over the life-force of the body, attaining the power to shed the physical body at will or to retain it for an indefinite period of time.

Among such masters of yoga are Lokanath Brahmachari, who lived for 166 years and Shivapuri Baba, the great yogi and master of alchemy, who died in 1963 at the age of 137 years. Swami Rama of the Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy in Pennsylvania, USA, met an ageless yogi at the 1974 Kumbha Mela (a great spiritual fair held every 12 years in India). This yogi's name is Devraha Baba and he is said to be over 150 years old. It was discovered that he eats only fruits and vegetables, and practises certain aspects of yoga regularly.

Paramhansa Yogananda stated in his Autobiography of a Yogi that Lahiri Mahasaya had a very famous friend called Swami Trailanga, who was reputed to be over 300 years old. But the most amazing of them all must be the divine Mahavatar Babaji of the Himalayas, the guru of Lahiri Mahasaya and the Paramguru of Paramhansa Yogananda. Babaji, the ‘divine Yogi Avatara’ is eternal, with an immortal body. He has miraculous powers and control over time, decay and death. He can materialize or de-materialize his physical body at will. His undecaying body requires no food and he appears to his spiritually advanced disciples in the Himalayas from time to time. There have been disciples, in this lifetime, who have seen him. You can read more about Babaji in Paramhansa Yogananda's inspiring book, Autobiography of A Yogi.

By understanding and experience in the knowledge and practice of Swara Yoga, pranayama, kriyas, asanas, deep meditation and deep selfless love for God and mankind one can prevent disease, preserve health and youth, and promote longevity.

THE FLOW OF BREATH (PRANA)

A very interesting and observable phenomenon of Swara Yoga is that the flow of air through the nostrils is very rarely equal. This again can be experienced and tested by moistening the back of the hand and breathing on it, to feel in which nostril the air is flowing more predominantly, or to feel if they are flowing equally.

During the course of a day, the flow of air or prana is dominantly flowing in either the left nostril (ida nadi) or the right (pingala nadi), or evenly flowing through both (sushumna nadi).

When the breath and the nadis are functioning normally, the breath flow alternates between the left and the right nostril every two hours. Physiologically this occurs because of a mild swelling and expansion of the tissue covering the nasal turbinates and the septum within one of the nostrils. This results in one nostril gradually becoming obstructed, which decreases the flow of air in that nostril, which in turn causes a shift in the flow of air to the opposite nostril.

During the few minutes when nostril dominance is changing, the air flows more evenly through both. This alternation of the natural breath flow in each nostril is due to biological changes caused by the mind's fluctuating mental states, and to environmental and lunar influences.

The Swara yogis discovered through their studies of healthy, balanced people during the waxing and waning of the moon, that the breath flow in the nostrils was affected by the lunar energies. They observed that at sunrise, the breath flow rises in the left nostril (ida nadi) on the first lunar day when the moon is waxing (bright fortnight). Then the breath flow alternates at the end of each hour, moving from the left nostril (ida nadi) to the right (pingala nadi). The breath flow then continues alternating from one nostril to the other every hour for three days. On the fourth day at sunrise the breath flow rises in the right nostril (pingala nadi).

At sunrise, on the first lunar day, when the moon is waning (dark fortnight), the breath flow is reversed and begins rising in the right nostril (pingala nadi).

When the breath flow is dominant in the right nostril a person is more inclined to physical action than to thinking or intellectual pursuits. This is because the right nostril is associated with the sun current, warmth, heat, action and the physical. Left-brain activity becomes dominant.

The inclination to action is reversed when the left nostril is dominant, producing a calmer state of mind. The cool moon current influences the right-brain tendencies of introspection, mental creativity and creative imagination.

This flow of breath is constantly alternating from one nostril to the other approximately every one and three quarters to two hours. Apparently this is a natural rhythm, but it can change with our fluctuating mental and emotional states, activities, disease, stress and the unbalancing of our daily routines. This natural rhythmic cycle is necessary for balancing the mind and body. Without this balance, serious harm can occur. If the breath were to flow in only one nostril for 24 hours or more, then one would become very ill — there would be an imbalance.

When the breath is flowing equally through both nostrils then the sushumna (the central nadi) functions. In this balanced state, the mental processes are clear and calm; the body and the breath are calm and steady. Meditation and contemplation become effortless when the breath is flowing in the sushumna. But when either the mind or breath becomes restless, this brings about a disturbance in the balance of the breath flow in the nadis.

If one is to be successful in meditation then sushumna must be flowing. If pingala flows the body will be restless; if ida flows, thoughts will distract you from meditating.

HOW TO BALANCE AND CHANGE THE FLOW

There are various methods for changing the flow of breath in the nadis. If you wish to change the flow from the right nostril to the left, you can use any of the following methods. To change from the left to the right, reverse the process.

• Lie down on your right side for ten minutes. It is traditional for yogis to sleep on their right side with the left nostril flow (ida) open for a calm, relaxing sleep. If the pingala flows predominantly at night you may become restless and find it difficult to sleep.

• Squeeze your left hand under your right arm, so that the fingers are pressing into the armpit.

• Close off your right nostril with a piece of cotton wool for a few minutes, until the flow changes to the left nostril.

• Practise nauli kriya (see chapter 4).

• Practise kechari mudra (see chapter 4).

• Use will-power to change the flow.

• To balance the nadis by changing the flow to the sushumna, concentrate at the point between the eyebrows (the spiritual eye), or concentrate on any one of the chakras. When your body is steady and your spine straight, seated in asana, with your mind concentrated and quiet, then your sushumna functions.

• Practise padadirasana (see page 181) to keep the flow even in both nostrils.

PURIFICATION OF THE NADIS THROUGH PRANAYAMA

The Nadis

The nadis are a network of astral nerves situated throughout the astral body. The two main nadis are the ida and the pingala. The ida and the pingala correspond to the left and right sympathetic nerve cords in the physical body. Through these astral tubes flows the vital life-force, called prana. In between these two nadis is the sushumna nadi, which is the most important of all the nadis. The sushumna nadi is the central channel into which the yogi tries to direct the pranic flow, so as to stimulate and awaken the kundalini shakti (a force of energy).

Throughout the subtle or astral body there are about 72,000 nadis which circulate prana throughout the body. In the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, a Vedic scripture, which is the oldest of the Upanishads, dating from about 800 BC, it says that the nadis are as fine as a hair split into 1,000.

The nadis’ source, which is egg-shaped and called kanda, is located between the anus and the root of the genitals, just above the muladhara chakra. This is also the junction of the sushumna and the muladhara chakra. From kanda the nadis distribute prana all over the body.

One way of purifying the nadis is to practise the shatkarmas (see chapter 4), but some Westerners find these rather strenuous and tiring.

Another way is to practise the following purification exercises in the exact order as given:

1 nadi shuddhi (alternate nostril breathing)

2 kapalabhati (skull-shining breathing)

3 agni sara dhauti (fire wash)

4 ashwini mudra (horse mudra)

Practise these techniques for a period of three months before beginning your pranayama programme. They will purify the nadis and strengthen and purify the nerves of the physical body. The last three techniques are explained in chapter 4. The following is the technique for nadi shuddhi.

Nadi Shuddhi: Alternate Nostril Breathing

This pranayama is also known as anuloma-viloma when breath retention is added.

This nerve-purifying breathing also maintains an equilibrium in the catabolic and anabolic processes in the body. It purifies the blood and the brain cells. It has a soothing effect on the nervous system.

For the yogi it is usual to make the breath flow in each nostril exactly the same. When the flow of air is equal in each nostril, then the flow in the ida and pingala nadis is also the same — they become balanced. Under these balanced conditions, prana begins to flow in the central main nadi (sushumna).

1 Begin by sitting comfortably in asana, with the head, neck and spine in a straight line. Keep the body still and relaxed.

2 Place your left hand on your left knee, relaxed, and raise the right hand to your face. Make the vishnu mudra by folding down your index and middle fingers.

3 Exhale through both nostrils. Then close your right nostril with your thumb and inhale slowly and deeply through your left nostril.

4 Close your left nostril with your third and fourth fingers, release your thumb and exhale through your right nostril.

5 Inhale through your right nostril, then close it with your thumb and exhale through your left nostril.

This completes one round. To start with, practise only ten rounds, then gradually increase to 40 rounds by increasing by one round each week.

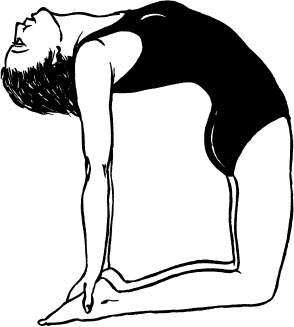

The relative measures of breath inhalation (purak), retention (kumbak) and exhalation (rechak) are:

• 1: 2: 2 for beginners who are advised to follow this ratio for a few months before taking up the advanced ratio.

• 1: 4: 2 for advanced students of pranayama

For beginners this means that the breath retention is twice that of the inhalation, and the period of exhalation is the same as that of the retention. For advanced students it means that the breath retention is four times that of the inhalation, and the period of exhalation is twice that of the inhalation.

The minimum starting proportion for a beginner is 4: 8: 8 (if this is difficult then start from 2: 4: 4). After having practised this ratio for one month, then increase the ratio to 5: 10: 10. Then increase gradually until you reach 8: 16: 16. On no account should you increase this proportion until you are able to practise it with comfort and ease. You must never force or strain the breath and lungs; to do so could cause damage to the physical body. If you are not sure then consult a qualified teacher who practises pranayama.

As you progress with these ratios, you will be able to change to the advanced ratio of 1: 4: 2, gradually working up to 8: 32: 16, which could take all of two years’ practice to reach. A student who wants to go beyond this limit is advised to seek personal instruction from a competent teacher of pranayama.

Commence with three rounds, gradually increasing to 20. Increase the proportionate ratios and the number of rounds very slowly.

When the breath is retained for longer than ten seconds, then it is important to hold jalandhara bandha (chin lock). See chapter 4 for the technique.

Nadi Shuddhi Exercises for Beginners

1 Practise ten rounds of inhaling and exhaling through the left nostril. Then repeat ten rounds of inhaling and exhaling through the right nostril. (Simple breathing — no ratio).

2 Practise ten rounds of inhaling through the left nostril, then exhaling through the right. Repeat ten rounds of inhaling through the right nostril and exhaling through the left (Simple breathing — no ratio).

3 Practise five rounds of inhaling through the left nostril, holding the breath for five seconds, and exhaling through the right nostril.

4 Practise five rounds of inhaling through the right nostril, holding the breath for five seconds, and exhaling through the left nostril.

5 Inhale through the left nostril. Hold the breath inside. Exhale through the right nostril, and retain the breath outside. Breathe in through the right nostril. Retain the breath inside. Exhale through the left nostril and retain the breath outside. Practise this simple breathing without a proportionate ratio for five rounds.

This uses internal and external breath retention antaranga kumbhaka and bahiranga kumbhaka. The starting ratio for this is 1: 4: 2: 2, and as in the other exercises, it should be increased gradually over a period of time.

Advanced Nadi Shuddhi

The following three practices must only be done by those who have advanced sufficiently to be able to hold the breath comfortably with the use of bandhas for one minute. One needs to have practised the basic pranayamas using proportionate ratios for at least one year, and be experienced in applying the bandhas when retaining the breath internally and externally.

The following practices use the ratio, 16: 64: 32.

First pranayama

1 Sit in the lotus posture (padmasana) or siddhasana and meditate on the element of air (vayu), which is a smoky colour.

2 Inhale through the left nostril and mentally repeat the bija mantra yam as you breathe in for a count of 16 seconds.

3 Hold your breath until you have mentally repeated the yam 64 times.

4 Exhale through the right nostril, until you have mentally repeated yam 32 times.

Second pranayama

1 Sit in padmasana or siddhasana and meditate on the element of fire (agni).

2 Inhale through your right nostril, mentally repeating 16 times with the breath, the agni bija mantra ram.

3 Hold your breath until you have mentally repeated ram 64 times.

4 Exhale through your left nostril until you have mentally repeated ram 32 times.

Third pranayama

1 Sit in padmasana or siddhasana with your inner attention focused at the spiritual eye, the point between the eyebrows.

2 Inhale through your left nostril, mentally repeating the bija mantra tham with the breath 16 times.

3 Hold your breath until you have mentally repeated the tham 64 times. Simultaneously, visualize the cool nectar from the moon flowing through all the vessels and nadis of your body, purifying them.

4 Exhale through your right nostril, mentally repeating the earth element (prithvi) bija mantra lam, 32 times.

FOUR DIFFERENT METHODS OF BREATHING

In yoga the breathing process is classified into four general methods:

• abdominal or diaphragmatic or low breathing

• intercostal or middle breathing

• clavicular or upper breathing

• complete yogic breathing (which is a combination of low, middle and upper breathing)

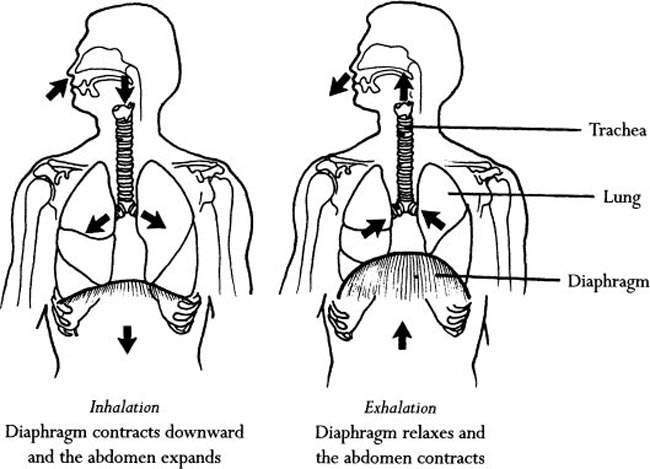

Abdominal breathing is associated with the movement of the diaphragm and the outer wall of the abdomen. When relaxed the diaphragm muscle arches upwards like a parachute into the chest region. During inhalation the diaphragm muscle is flattened from a dome shape to a disc shape, as it moves downwards. This compresses the abdominal organs and eventually pushes the front wall, the navel, of the abdomen outwards. This movement enlarges the chest cavity downwards and allows the diaphragm to move upwards again, to reduce the volume in the chest cavity, which causes exhalation.

This form of breathing is physiologically the most efficient because it draws in the greatest amount of air for the least amount of muscular effort.

In Intercostal breathing the movement of the ribs is brought into play. During expansion of the ribcage outwards and upwards by muscular contraction, the lungs are allowed to expand. This results in air being drawn down into them from the front side and inhalation taking place. The intercostal muscles control the movements of the ribs — when they are relaxed, then the ribs move downwards and inwards. This movement compresses the lungs and exhalation takes place.

In Clavicular breathing, inhalation and deflation of the lungs is achieved by raising the upper ribs, shoulders and collarbones (clavicles). This method requires maximum effort to obtain minimum benefit. Very little air is inhaled and exhaled, since this movement cannot change the volume of the chest cavity very much. Upper breathing is common in Western society, owing to the modern lifestyles we have adopted, particularly in the cities and large towns where we are more open to stressful conditions — pollution, noise, overheated and unventilated rooms and offices, badly designed chairs and other people's smoke. We get into a state of anxiety or we immobilize our diaphragm in an attempt to contain our fears of aggression and other deep emotional feelings, causing us to breathe shallowly in the upper chest.

Complete yogic breathing combines all the above modes of breathing into one complete harmonious movement. In that form of respiration the entire respiratory system is brought into use — all the respiratory muscles including the internal and external intercostals and abdominal muscles; the ribcage; every part of the lungs and their air cells; and the diaphragm. It is this type of breathing that we are interested in developing, since only yogic breathing can give the maximum inhalation and exhalation of breath.

COMPLETE YOGIC BREATH PRACTISED IN SECTIONS

The purpose of this practice is to make you aware of the three different types of respiration, and to incorporate them into the complete yogic breath. It also corrects shallow breathing and calms the mind.

For the practice of these exercises sit in a comfortable posture, either cross-legged or in vajrasana, with the spine straight in a warm but well-ventilated room. All breathing should be performed through the nostrils and not through the mouth.

Abdominal Breathing (Adham Pranayama)

1 Place the palms of your hands lightly on your abdomen. This is to make you aware of the movement in your abdomen as the air is breathed in and out of the lowest lobes of your lungs. Breathe out slowly and completely, remembering that it is the movement of your diaphragm that is responsible for your abdominal breathing. As you exhale, feel your abdomen contract; your navel will move toward the spine. At the end of exhalation the diaphragm will be totally relaxed and will be doming or parachuting upwards into the chest cavity.

2 Now hold your breath for one or two seconds.

3 Inhale, without expanding your chest or moving your shoulders. Feel your abdomen expand, the navel moving upwards. The breathing should be deep and slow. At the end of the inhalation your diaphragm will be bowing in the direction of the abdomen and your navel will be at its highest point.

4 Hold the breath for one or two seconds.

5 Exhale again, slowly and completely. At the end of the exhalation your abdomen will be contracted. Hold the breath for a short time, inhale and then repeat the whole process twice more.

6 Now move your hands around to your back, so that your palms are resting on your lower back, with the fingers pointing towards the spine. Concentrate your mind on the movement of the lungs beneath your hands as you breathe. Repeat the same breathing process as you did for the abdomen three times.

Middle or Intercostal Breathing (Madhyam Pranayama)

In this practice the idea is to breathe by utilizing the movement of the ribcage. Throughout this practice try not to move the abdomen; this is achieved by slightly contracting the abdominal muscles.

1 Place your palms either side of the middle ribcage, so that the fingers of each hand are pointing towards each other. This is to feel the expansion and contraction of the ribs. The intercostals (the muscles between the ribs) swing the ribs upwards and forwards, increasing the diameter of the chest and expanding the lungs, while the internal intercostals pull the ribs down, causing a reduction in lung volume.

2 Breathe in slowly by expanding the ribcage outwards and upwards. You will find it impossible to breathe deeply because of the limitation on the maximum expansion of the chest.

3 At the end of the inhalation, hold your breath for one or two seconds.

4 Slowly exhale by contracting the chest downwards and inwards. Keep the abdomen slightly contracted, but without strain.

5 Breathe in slowly. Repeat the whole process twice more.

6 Then place your hands behind the mid-area of your back, opposite to where you had your hands placed on your front. Again, concentrate and breathe into the middle back area for three rounds.

Upper or Clavicular Breathing (Adhyam Pranayama)

In this practice try not to expand or contract your abdomen or chest — not easy to do.

1 Place both palms on your upper chest, above your breasts, so that you can determine whether your chest is moving or not, while trying not to contract the muscles of your abdomen.

2 Inhale by drawing your collarbones and shoulders towards your chin. You may find this difficult at first, but persevere. A good method is to inhale and exhale with a sniffing action, which automatically induces upper breathing.

3 Exhale by letting your shoulders and collarbones move away from your chin.

4 Practise this technique twice more.

5 Then place your hands on your hips, keeping your armpits open. With concentration breathe into the side high lobes of the lungs, so that you feel the movement and breath under the armpits.

6 Repeat this process twice more, then raise your arms over your shoulders, and over the higher lobes of the lungs. Breathe deeply and slowly into this area three times with concentration.

The Complete Yogic Breath Technique

The combination of the three types of breathing — low, middle and upper — takes the optimum volume of air into the lungs and expels the maximum amount of carbon dioxide.

1 Breathe out deeply, contracting the abdomen to squeeze all the air from the lungs.

2 Inhale slowly, keeping the lower part of the abdomen contracted, while expanding the part above the navel slightly. The reason for this is that if you push the lower abdomen out, you are likely to acquire a pot belly due to the abdominal organs moving down and forward.

3 At the end of the upper abdomen expansion, start to expand your chest and ribcage outwards and upwards. Continue drawing the breath upwards into the higher lobes of your lungs by raising your collarbones and shoulders towards your head. Your lungs should now be completely filled with air.

4 Hold your breath in for a few seconds, with the head forward in jalandhara bandha (see chapter 4). This is practised by gently dropping the head forward so that the chin rests in the notch between the collarbones. Do not strain or force your neck into the position, but keep the neck and throat muscles soft and relaxed. Move your chest upwards to meet your chin as you bring it down, then you will not strain the neck or throat. Only hold jalandhara bandha for a few seconds or for as long as is comfortable while holding the breath.

5 Release the chin lock by raising your head and begin to exhale, first relaxing your collarbones and shoulders. Then allow your chest to move first downwards and then inwards. After this allow the abdomen to contract. Do not strain but try to empty your lungs as much as possible, squeezing all the air out by drawing the abdominal wall closer to the spine.

6 Hold your breath out for a few seconds. This completes one round of yogic breathing. Now take a few normal breaths, then practise another five rounds.

Figure 19 Yogic Breathing

The whole movement should be one continuous movement, each phase of breathing merging into the next, without there being any obvious transition point. There should be no strain or jerky movements with the body or breath. The body should remain relaxed throughout the practice. With practice you will find that the whole process will occur naturally with no undue effort.

The reason for practising jalandhara bandha (chin lock) is to retain the pressure of the air within the lungs so as to reduce any pressure in the brain and regulate the flow of blood and prana to the head, heart and thyroid glands in the throat.

This practice develops good healthy lung tissues which resist germs, making you much less susceptible to disease. The blood receives plenty of oxygen and every organ of the body is nourished by it. Digestion and assimilation are improved, and bodily energy and vigour are increased. The nervous system and the brain benefit through the blood being properly oxygenated, making them more efficient instruments for generating, storing and transmitting the nerve currents. Clarity of thought is improved.

To develop yogic breathing as an automatic and normal function of the body, develop the habit of consciously breathing yogically for a few minutes whenever you can throughout the day. If you feel tired, depressed, angry or anxious, then become centred within yourself and sit down, or if possible lie down, and practise yogic breathing. Breathe deeply and slowly with your concentration on the breath. Feel that you are inhaling not just air, but joy, peace, strength, courage or whatever positive quality you want especially to affirm. As you exhale, breathe away any negative qualities that your mind may be holding on to. Then your mind will become calm and revitalized.

HAND MUDRAS FOR CONTROLLING THE BREATH

The hand mudras covered in this section control the physical functions of the breathing. The mudra achieves this by controlling the mind-brain processes and the functions within the nervous system by uniting various nerve terminals of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

In chapter 4, we discussed the main mudras, such as yoni mudra in which the state of pratyahara (sense withdrawal) is brought about by the pressure of the fingers on the face, upon the vagus and the facial nerves, which are brought together in a closed circuit. In yoni mudra, which was also discussed in chapter 4, the hands are united with the feet, which causes the vagus nerve system to be close-circuited with the cerebrospinal nerves.

When the hands are placed together palm to palm, as in the praying gesture of the Christians, Jews and Hindus, the cranial nerve circuits in the head and the upper part of the body in the pneumogastric or vagus nerve system are united together.

The right lung is divided into three separate compartments or lobes: the lower abdominal lobe, the middle intracostal lobe and the high clavicular or superior lobe. The left lung has only two lobes: the lower and the higher.

A section of the brain controls each of these lung lobes via the nervous system. By applying the hand mudras in certain combinations, each lobe can be inflated and deflated independently of one another. This gives one greater control over the breath and prana.

In some of the pranayama techniques which follow, we will use five basic hand mudras:

• Chinmaya or jnana mudra. This controls abdominal breathing (adham pranayama). Make a circle by joining together the tip of the thumb and the first finger. The other three fingers are kept outstretched and together.

• Chin mudra (the symbol of wisdom). This controls the middle lobes of the lungs (madhyam pranayama). Join together the tip of the thumb and the first finger to form a circle. The other three fingers are folded into the palm of the hand, with the tips of the fingers tightly pressed in.

• Adhi mudra. This controls the high clavicular or superior lobes of the lungs (adhyam pranayama). Fold the thumb into your palm and fold the other fingers over the thumb, clenching them into a fist.

• Brahma mudra. This controls complete yogic breathing (mahat yoga pranayama) in each of the three parts of the lungs. The hands are clenched into position as in adhi mudra, then the knuckles where the fingers join the hand are pressed together, hand to hand, with the fingers turned upwards. The hands in this position are then lowered below the diaphragm, in front of the navel.

• Shunya mudra (shunya means vacuum or void). This mudra keeps a lobe of the lung empty while others are being inflated. Open one palm, with the thumb at a 90-degree angle to the palm. Make sure the fingers are extended and tightly together. Place the hand, palm upward, on the junction of the thigh close in to the body.

VIBHAGA PRANAYAMA: SECTIONAL BREATHING

This practice calms the mind and increases the air intake into the lungs. It harmoniously develops the various parts of the lungs.

1 Sit in vajrasana, close your eyes and relax. Place your hands in chin mudra, position both hands palms down at the top of your thighs, close to your groin, with the fingers turned inwards. Now inhale from the abdomen, then exhale. Practise six rounds of this breath.

2 Place your hands in chinmaya mudra, position both hands at the top of the thighs again. Breathe into the mid-chest lobes of the lungs. The intercostal muscles between the ribs expand and the rib cage opens like an accordion. Inhale and exhale six times.

3 Now position your hands in adhi mudra by clenching your fists, with the thumbs inside touching the palms. Place your hands fingers down on your upper thighs close to the groin. Inhale into the upper lobes of your lungs (just below the collarbones), then exhale. Practise this breathing six times.

4 With your hands still in adhi mudra, place both hands together in front of the navel, with the knuckles of each hand pressed together and turned upwards in brahma mudra. Now inhale a complete yogic breath, combining the three stages of lower, middle and upper breathing in one long, slow, deep, smooth continuous breath. Then exhale; the breath will empty out first from the lower lungs, then the middle, followed by the upper lungs.

Controlling the Breath with Shunya Mudra

1 Sit in vajrasana, close your eyes and relax.

2 Place your left hand in any one of the following mudras: chin, chinmaya or adhi. The palm should be resting on the top of your left thigh close to your body. Place your right hand in shunya mudra, palm upwards on top of the right thigh.

3 Now inhale deeply and you will find that the lobe of the lung on the right side will not be activated; it will remain empty, while the left lobe of the lung indicated by the mudra of your left hand will inflate and deflate with the respiration.

4 Reverse the mudras, so that you have your left hand in shunya mudra and your right hand in chin, chinmaya or adhi. Then breathe in deeply.

5 You can also try controlling the breath in various lobes of the lungs by using chin, chinmaya or adhi mudra with both the left and right hand using different combinations. For example, if you have the left hand in chin mudra and the right hand in adhi mudra you will get the extraordinary feeling of the breath crossing diagonally from the lower lobe of the left lung to the upper lobe of the right lung as you inhale deeply.

PRANAYAMA TECHNIQUES

SUKHA PRANAYAMA: PLEASANT BREATH

Exercise 1: This is a very simple pranayama that even children and convalescents can practise. It simply involves inhaling and exhaling equally through both nostrils, but it is important to make sure that the inhalation is of the same duration as the exhalation. To begin with you can use a metronome or the tick of a clock for counting the breaths.

Practise the following breathing ratios:

| INHALE | EXHALE |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 5 (good for people who are always late) |

| 6 | 6 (good for neurotic and psychotic people) |

| 7 | 7 (good for introverts) |

Exercise 2: Loma Pranayama: This is a three-part equal breath ratio: inhale for six, retain for six, exhale for six (6: 6: 6). Practise a minimum of nine rounds every morning and gradually increase to 27 rounds.

Exercise 3: Viloma Pranayama: This is also called inverse breathing. Inhale for six, exhale for six, external retention for six (6: 6: 6). Practise nine rounds and gradually increase to 27 rounds. This is good for mothers with a young child. Hold the child and breathe in this ratio. The child will naturally breathe with you.

Exercise 4: Sukha Purvaka Pranayama: Inhale for six, retain for six, exhale for six, external retention for six (6: 6: 6: 6).

PANCHA SAHITA PRANAYAMA: THE FIVE-PART-RATIO BREATH

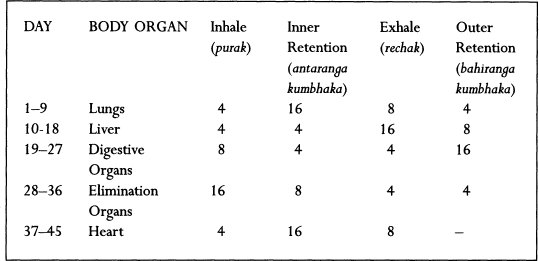

The pancha sahita pranayama concentrates on rejuvenating five important body organs — the lungs, liver, digestive organs, elimination organs and heart — using the classical pranayama anuloma-viloma over a period of 45 days. It controls the five elements associated with the five body organs and the five pranic flows (prana vayus).

The best times to practise this pranayama are at sunrise, midday and at sunset.

1 Sit comfortably with your head, neck and spine in a straight line in a meditative asana.

2 Practise nine rounds of anuloma-viloma pranayama using the proportionate ratio of 4: 16: 8: 4 (to rejuvenate the lungs) three or four times a day, for nine days. The four count is for the inhalation; the sixteen count for the internal breath retention; the eight count for the exhalation and the four count for the external breath retention.

3 On the tenth day, change the breathing ratio to 4: 4: 16: 8 (to rejuvenate the liver). Again, practise three or four times a day, for nine days.

4 Continue with the rejuvenation of the other three organs. To make this clearer use this chart for easy reference.

This entire pranayama routine can be practised once every three months.

Remember to apply jalandhara bandha during inner breath retentions of over ten seconds.

BHASTRIKA PRANAYAMA: BELLOWS

The Sanskrit word bhastrika means ‘bellows’. Just as a blacksmith's bellows blow air vigorously and rapidly to fan the flames of the fire, so in this practice, the practitioner inhales and exhales rapidly in the same way.

This pranayama can awaken the kundalini shakti if the nadis and nervous system are purified.

Within the sushumna in the spinal column are three granthis (knots). These knots or energy blocks prevent the free movement of the prana energy in the sushumna.

They are:

• Brahma granthi — muladhara chakra

• Vishnu granthi — manipura chakra

• Rudra granthi — ajna chakra

To free the pranic current and break these knots, one needs to perform bhastrika pranayama. When they are broken, the kundalini is free to rise gradually toward the sahasrara chakra (crown centre), the subtle counterpart of the brain.

1 Sit in a comfortable asana, preferably padmasana or siddhasana, with the spine straight. Relax and close your eyes.

2 Inhale and exhale through both nostrils vigorously and rapidly, so that the expulsions of breath follow one another in rapid succession. This will bring into rapid action both the diaphragm and the entire respiratory apparatus. One rapid inhalation and exhalation completes one bhastrika breath.

3 Practise ten breaths, breathing out deeply on the tenth expulsion. Then take a long, slow, deep inhalation through both nostrils.

4 Retain the breath for as long as is comfortable, applying jalandhara bandha (chin lock) and mulabandha (anal lock) (see chapter 4), with your awareness and concentration on the kundalini in the muladhara chakra.

5 Release the chin lock, then the anal lock, and exhale slowly.

This completes one round of bhastrika. Take a short rest between each round by taking a few normal breaths. As you progress you can gradually increase the number of breaths from ten to 15, 20, 25, 30 and so on up to 120 in each round.

Beginners should start with three to five rounds of ten breaths and gradually increase to a maximum of 30 over a period of months. Advanced students should gradually work up to 120 breaths in each round as a maximum. The rounds can be increased from 20 in the morning to 20 in the evening. The breath retention (kumbhaka) can also gradually be increased, but with care and proper guidance from a qualified and experienced teacher of pranayama.

This practice increases the supply of blood to the brain, tones the entire nervous system, increases the gastric fire and gives warmth to the body. It helps to cure diseases of the lungs, awakens kundalini, activates the ajna and sahasrara chakras and induces tranquillity to the mind.

However, people with high blood pressure, vertigo or heart ailments should not practise it, and beginners should practise cautiously and seek expert guidance, for this is a powerful pranayama.

Alternate Nostril Bhastrika (Variation 1)

1 Sit in vajrasana and inhale deeply through both nostrils, as you raise your arms above your head and circle them three times while holding the breath. Keep your chest open and lower the left arm, so that you rest your left hand with the palm upwards in your lap.

2 Place the index finger and second finger of your right hand at the point between the eyebrows, and close your left nostril with your third finger. Exhale slowly and deeply through your right nostril, then take a short inhalation through the same nostril and begin the bhastrika breathing in the right nostril for ten breaths.

3 On the tenth expulsion, hold the breath out, and apply the three bandhas: jalandhara, uddiyana and then mula (see chapter 4). Hold it for as long as is comfortable, without strain. Then release mulabandha first, then uddiyana, followed by jalandhara.

4 Inhale slowly and deeply through the right nostril and hold the breath in for as long as is comfortable, applying the chin lock and anal lock. Release the locks and exhale through the right nostril.

5 Return to normal breathing. This completes one round. Take a short rest before starting steps 1–4 with the left nostril.

The number of rounds and breaths are the same as for the last exercise.

Alternate Nostril Bhastrika (Variation 2)

1 Sit upright in a comfortable asana, relax and close your eyes.

2 Place your hands in vishnu mudra (the thumb of the right hand is used to close the right nostril and direct the pingala energies. The third and fourth fingers are used to close the left nostril and direct the ida energies).

3 Inhale through the left nostril, exhale through the right nostril, inhale through the right, exhale through the left, inhale through the left and so on. Start slowly at first, then begin to speed the movements up, so that the hand movements which are alternating the breath rapidly in each nostril are synchronized with the breath.

Note: Bhastrika pranayama is best practised after nadi shuddhi (see pages 190–3).

Bhastrika and Kapalabhati

Kapalabhati is one of the purification exercises (shatkarmas) described in chapter 4. The difference between bhastrika and kapalabhati is that in bhastrika the breath is retained at the end of each round with the three bandhas to unite the prana and apana. In kapalabhati there is no breath retention.

Kapalabhati also differs in that the inhalation is long and mild, and the exhalation is forceful and rapid, whereas in bhastrika, the inhalation is as rapid as the exhalation.

In the beginning practise ten breath expulsions for one round, gradually increasing by ten expulsions each week until you reach a maximum of 120. Practise three rounds at each sitting. Alternatively you can practise 20 expulsions for each round, making six rounds (120 expulsions).

There are three breathing rates that you can use with kapalabhati:

• mild speed — one expulsion per second (60 per minute)

• medium speed — two expulsions per second (120 per minute)

• fast speed — four expulsions per second (240 per minute)

The beginner should practise the mild kapalabhati.

SURYA BHEDA PRANAYAMA

The Sanskrit word surya means sun and bheda means ‘to pierce’ to ‘pass through’. Surya bheda pranayama activates the solar, right nostril (pingala nadi).

1 Sit in a meditative posture, preferably padmasana or siddhasana. Relax and close your eyes.

2 Raise your right hand and place your fingers in vishnu mudra. Close your left nostril with your third and fourth fingers. Inhale slowly, deeply and quietly through your right nostril. Be totally aware as you inhale.

3 Close both nostrils and retain your breath. Apply the chin lock (jalandhara bandha) and the anal lock (mulabandha). Hold your breath without straining, for as long as is comfortable.

4 Release mulabandha first, then jalandhara bandha, and exhale slowly, deeply and quietly through your left nostril.

This completes one round. Without pausing, close your left nostril and again inhale through your right nostril, repeating steps 1–4.

Beginners should start with shorter breath retentions, gradually increasing the retention time as the lung capacity develops. You should also start with ten rounds, gradually increasing over a period of time to 40.

The Gheranda Samhita says that the practice of surya bheda destroys disease and death and awakens the kundalini. It awakens the kundalini by taking the prana into the sushumna. It purifies the brain and frontal sinuses. The digestion is stimulated and the nerves are invigorated and soothed — in fact the whole body is given a general tonic by this practice. It increases heat in the body so it is best to practise it during the winter months.

However, do not practise immediately before or after meals, because the energy is needed for digestion. Also do not practise late at night before going to sleep, because the pingala nadi will be activated, which will keep you awake.

CHANDRA BHEDA PRANAYAMA

Chandra means ‘moon’. This pranayama is basically the same as the surya bheda except that all inhalations are through the left nostril, and the exhalations through the right.

In this practice the prana is channelled through the ida or chandra nadi, which cools the body system, whereas the surya bheda heats the system.

Note: Do not practise surya bheda and chandra bheda on the same day.

UJJAYI PRANAYAMA

The Sanskrit prefix ud, means ‘to raise upwards’, and jaya means ‘the victorious’.

1 Sit in a comfortable meditative posture, close your eyes and relax.

2 With your mouth closed, slowly and smoothly inhale and exhale through both nostrils, partially closing the glottis in the throat. This produces an even and continuous hissing or soft snoring type of sound.

3 During the inhalation the air is felt on the soft roof palate, accompanied by the sibilant sound ‘sa’, due to the friction of the air. The exhalation is also felt on the soft roof palate and produces the aspirate sound ‘ha’. During the inhalation (puraka) keep the abdominal muscles slightly contracted. Completely expand the lungs with air, by raising and expanding the ribs until the chest is thrust forward like a victorious warrior.

4 During the exhalation (rechaka) the abdominal muscles will naturally be more retracted. The duration of the exhalation is always longer than the inhalation, usually in the proportionate ratio of 1: 2. This means that if you inhale for five seconds, exhalation should be ten seconds.

5 Practise 5–20 rounds of ujjayi pranayama, starting with five and increasing by two rounds each week until you reach 20.

Advanced Ujjayi Pranayama

Advanced practitioners can perform mulabandha and jalandhara bandha with breath retention (kumbhaka).

1 After inhaling in ujjayi, completely close the glottis and perform mulabandha and jalandhara bandha.

2 After comfortably holding your breath (kumbhaka), first release mulabandha, then jalandhara bandha.

3 Exhale through your left nostril, by closing the right one with your thumb. This traditional way of exhalation through the left nostril requires less effort to breathe in the 1: 2 ratio. This is because exhalation through one nostril will require double the time of inhalation through both nostrils, provided the force of breathing is constant.

Ujjayi pranayama can be practised at any time and in all positions — yoga postures, standing and walking — safely without breath retention. To balance the prana and apana, keep the length of the inhalation and exhalation the same, and breathe through both nostrils evenly.

This practice calms the mind and nervous system and is good for hypertension, anxiety and depression. It slows the heartbeat and reduces high blood pressure. It is also good for people suffering from insomnia, asthma, pulmonary diseases and heart diseases. It helps in regulating the blood pressure, endocrinal secretions and gastrointestinal activity, removes phlegm from the throat and cools the head.

It is also good for those people who do not cry (crying from positive emotions becomes purifying).

Ujjayi improves concentration when the awareness follows the breath, and helps to bring one to a meditative state by awakening one's psychic energies.

SITALI PRANAYAMA

Sitali (pronounced ‘sheetali’) is a cooling breath, it has a cooling and soothing effect on the body.

1 Sitali can be practised sitting in a meditative asana or standing.