11.

“Would you put your seat belt on?” the driver said, and he accelerated hard.

As I reached for the seat belt, the driver spun the wheel to turn down a side street, throwing me against the passenger window.

“Sorry,” the driver said. “We’re in a hurry.”

I pulled the seat belt across me as fast as I could before he took another corner at the same speed. Which he did, just as I managed to guide the buckle home.

“Do you remember me?” the driver asked. I looked sideways. The man’s face was in profile; he was concentrating hard on the road ahead. In some ways the profile did look familiar, but I couldn’t place it.

“No,” I said. “But don’t take offense. The way things are, you could be my brother for all I know.”

“I’m not your brother.”

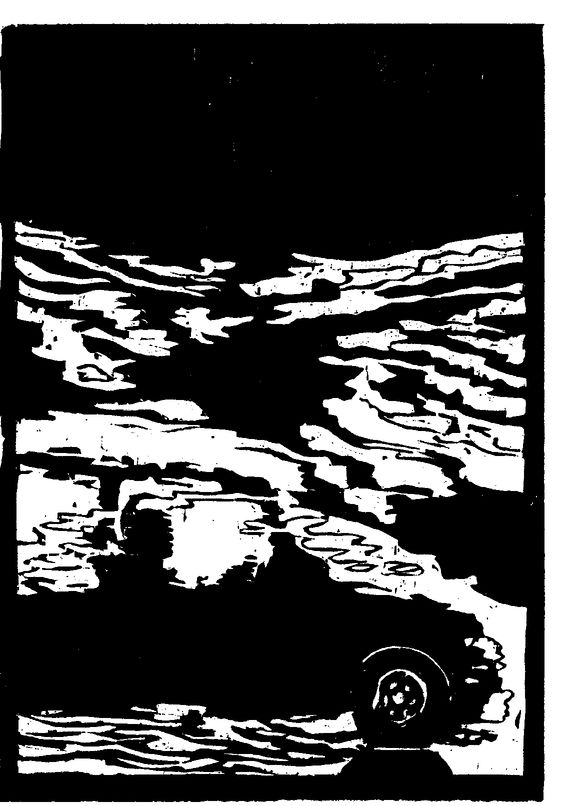

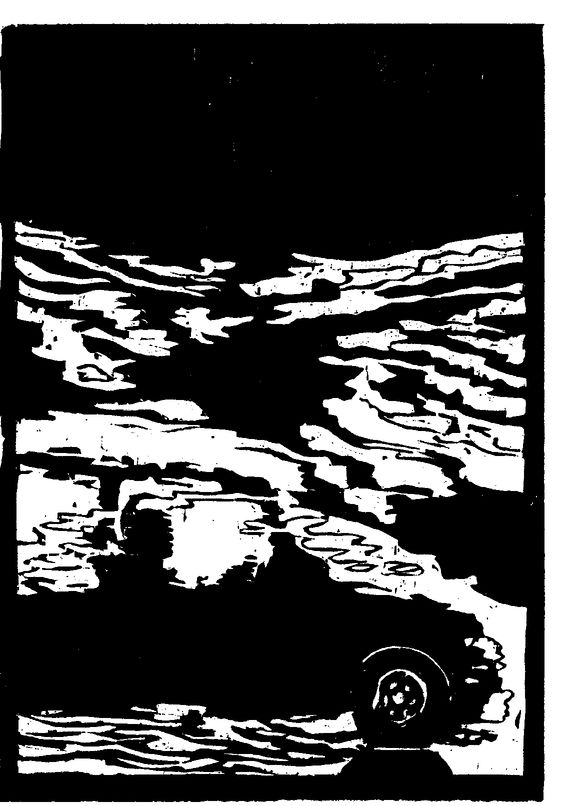

The driver braked quite hard for another corner, and I raised a hand to brace against the dashboard. This time when he swung the car around, we were turning off the residential streets and on to a slip road, joining a dual carriageway.

“Or my aunt,” I added. “You could be anyone.”

“I’m not your aunt either,” he said. “I gave you water. I helped you to sit up.”

I looked at the driver again. And this time I made the connection. It was the expression of concentration on his face—the same expression I had seen when the man was sitting by my bed at the hospital, talking to me, trying to wake me up.

“I do remember you,” I said. “You’re the nurse.”

“Yes,” he confirmed. “I’m the nurse.”

I glanced over at the dashboard. The needle on the speedometer was climbing fast. It passed sixty, then seventy, then eighty, then ninety.

“We really are in a hurry,” I said. “Where are we going?”

“Hospital,” the nurse replied, using the inside lane to overtake a string of cars.

“Then I am in trouble. My condition is going to deteriorate.”

“It may.”

I nodded. So much for relaxed fatalism, I thought, and felt a little surge of panic—which was not helped by the way in which our car was continuing to gain speed, now creeping past one hundred. “What happened?” I asked, injecting calm into my voice. “I imagine Mary or Anthony called the hospital and explained to you about my condition, and you tracked me down to—”

He cut me off. “Carl—there isn’t time for me to answer your questions. I need to ask you questions.”

“Of course,” I said. “Diagnosis. Okay.”

“Can you tell me what day it is?”

I thought for a moment. I wasn’t entirely surprised that I couldn’t provide the answer. In the best of health, I’ve lost track of the days. “No,” I replied.

“Or what year it is?”

“. . . No.”

“What can you tell me about your work?”

I thought again. And this time, I did feel surprised by the blankness I felt in response to the question. “I work with papers,” I said hesitantly. “I keep the papers in a briefcase with a brass clasp. And I work in a tall building. Somewhere in the center of . . . the city.”

“What city?”

I looked out the window at the high-rise flats that lined the dual carriageway. “I don’t know what city this is,” I said. And this time the surge of panic was unstoppable.

I felt as if I had been standing on the walkway of a dam that was breaking. And now it was broken. The endlessly rising speed of the car was my ejection on a plume of water.

And for a while, something that I knew was pure hallucination gripped me entirely, as the cars on the road became tumbling blocks of concrete and the road became tumbling foam, and the engine noise became the roar of a torrent that enveloped me.