7.

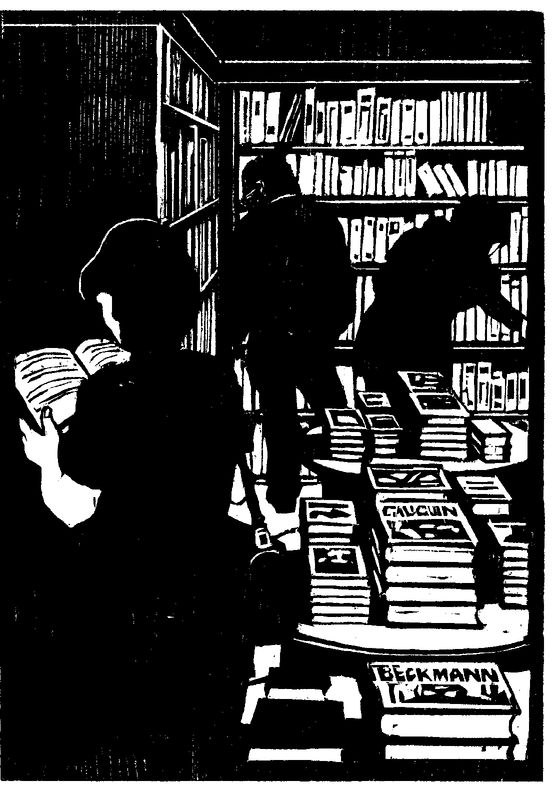

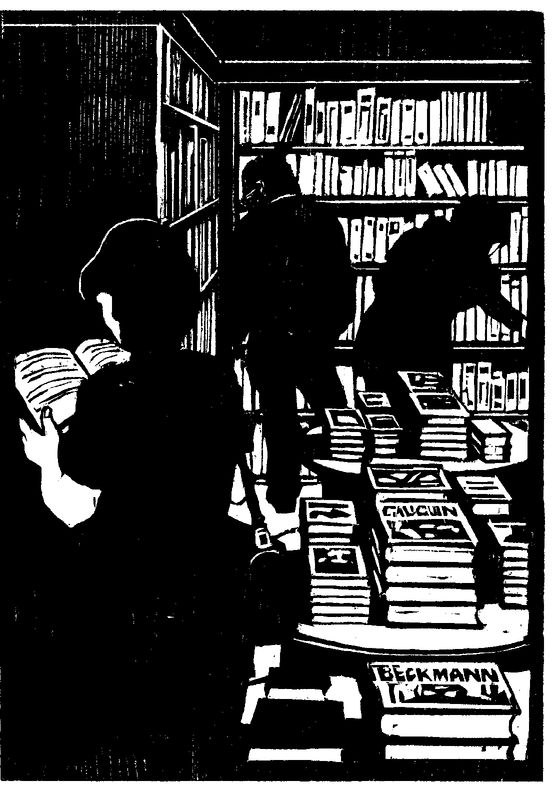

The experience in the bookshop was worse. I walked up to the shop assistant with a stack of literature I had pulled from the shelves, and lifted the first book on the pile. “This is one of the greatest novels ever written,” I said.

The girl examined the book jacket over the top of her glasses, then nodded her approval. “It’s wonderful. A classic. I’ve read it three times.”

“Three times? Really? How long did it take you?”

“Oh . . .” She looked surprised. “I don’t know. I read it first on holiday, and . . . Maybe a week or so.”

“A week? I just read the whole thing in less than a minute.”

“. . . A minute?”

“Do you want to know how?”

“Uh,” she said, glancing around nervously, “. . . I suppose so.”

“This is how.” I began flicking through the pages. “Because the only sentence in this entire book is ‘Call me Ishmael,’ written a few hundred thousand times. Tell me—do you think that constitutes great literature?”

“It ...”

“And how about this,” I said, showing her the second book in the pile. “Another great novel you can plow through in under three seconds. ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.’ Want to know what happens next?”

“I . . .”

“Tough. That’s all there is. But no problem, we’ll move on to The Catcher in the Rye.” I cleared my throat. “‘Pretty phoney,’ said Holden Caulfield. The end.”

“Sir . . .” said the girl.

“Wait. I haven’t got to Austen yet. ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged that a man in want of a woman is a man in need of things that a woman with needs can want to universally acknowledge.’” I closed the book with a snap. “It goes on in a similar vein for another three-hundred-odd pages. It makes you wonder why they teach it at school, don’t you think?”

“Sir,” said the girl, “I’m going to have to ask you to leave.”