8.

At the end of my street, we turned right on to the main road that led down to the river. It was mid-morning and the day was shaping up to be hot. Catherine was wearing a sun hat and a pretty summer dress, cotton, flower patterned. I was wearing jeans and a short-sleeved shirt, and I carried a small backpack with a water bottle inside and a camera.

Rather than walk the length of the main road in the growing heat and tire ourselves out, we chose to take the pedestrian subway, which had recently been extended. One could now travel the full distance to the river in air-conditioning, away from the traffic noise and exhaust fumes. One could even do a little shopping en route. Several outlets had opened up in the small alcoves that lined the walkway, most of them selling clothes and jewelry. It made the journey a little longer and a little slower than it might otherwise have been, because Catherine kept pausing to check the wares. I would be chatting away, in mid-sentence, and turn to look at her, only to realize that for the last few paces I had been talking to myself.

The pedestrian subway was also a little disorienting, because it was hard to judge how far one had traveled. Periodically there were staircases back to street level, but by some strange oversight, they had not yet been signposted to mark at which cross streets they exited. So we ended up guessing which exit to take and, by chance, chose the right one.

We came out at the bridge, where we paused to take a drink from the water bottle. We had been underground for perhaps half an hour, but already the day had got a good deal hotter. Either that or we had been softened by the air-conditioning. I began to wish I’d had Catherine’s good sense and brought a cap along, because I could tell that in this weather I was likely to burn.

“Where do you want to go?” I asked Catherine.

Catherine shrugged. She was leaning on the guardrail of the bridge, looking down at the slow-moving water below. “Do you think they eat their catch?” she said, indicating the fishermen who were sitting on the sloped concrete banks. “The river always looks so dirty.”

“I don’t think they do,” I said. “I think there may be a rule about having to put the catch back.”

But I wasn’t sure. A little way down the river, the banks were crowded with the wooden shacks and shanties where many of these fishermen lived. A different part of town, less affluent. Looking at their homes, it suddenly seemed unlikely they spent their days idly fishing for sport.

“I think they do eat them,” Catherine said, maybe having followed the same thought process as me. “I bet they taste of mud.”

“The fishermen or the fish?”

“Both.” She stood up from the guardrail. “How about we head through the antique district and then up to one of the shrines?”

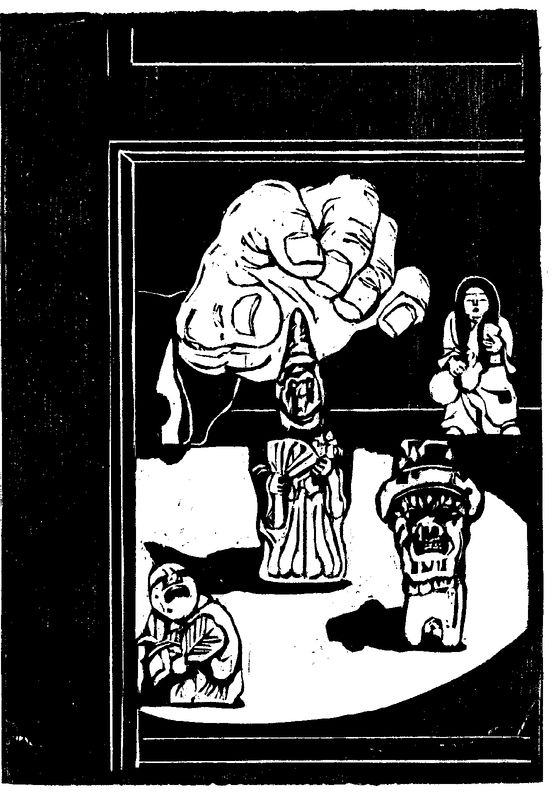

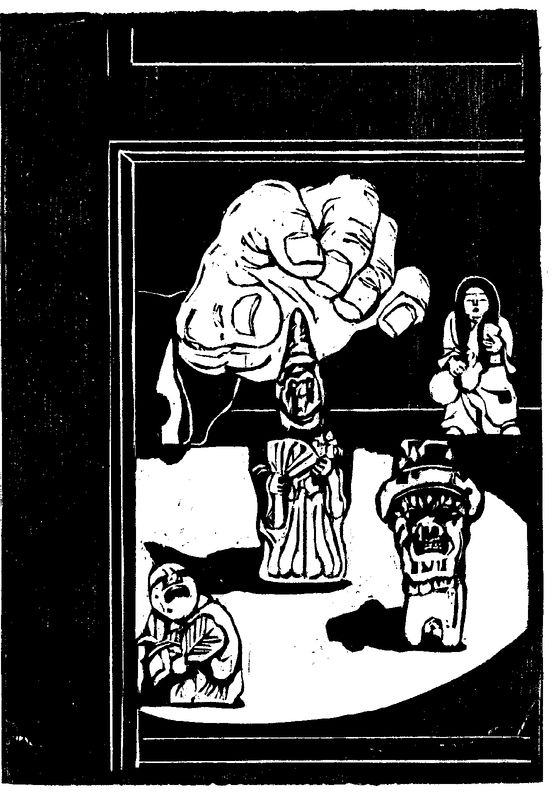

Now it was me who stopped at every shop window and Catherine who hovered impatiently ahead. I was distracted mainly by the small carved bone and ivory figurines that were for sale in most of the shops. The good ones were all far too expensive to buy, but I enjoyed looking at them, and I liked the smell of incense that floated out from the doorways.

One figurine caught my eye. It was an old man, squatting, with one hand resting on his knee and the other holding a fan. His head was angled, and he was looking straight up at me. He had an odd expression—a kind of grimace, slightly disapproving, but also angrily amused.

Beside the old man was another figurine, this one standing. It seemed even older than the rest, but it wasn’t ivory or bone. It looked as if it was made from clay or porcelain, and I wondered if this meant it would be more affordable than the others. The years had beaten it up a little. The glaze was cracked and chipped, and all of its protuberances—the folds of its clothes, its feet and hands—were worn down as if it had spent years knocking around inside someone’s pocket.

Examining it more closely, I saw that although the figurine was proportioned like a man and wearing clothes, a robe, its face was oddly pointed. Not a human face. There was a snout, doglike, but less pronounced.

As I looked at the curious face, a hand inside the shop picked it up. The shopkeeper, who looked not unlike the squatting old man I had been examining before, was gazing at me with the same odd grimace.

He held the standing figurine up to the window for me to see, then gave it a little flick on the back. And the dog face stuck its tongue out at me.

The shopkeeper’s grimace changed into a grin. This was his little trick to surprise customers. He did it a couple more times, and I saw that the tongue was loose in the head, a small sliver of bone. Its natural resting position was inside, but when the back was tapped, out it came.

The shopkeeper said something but I missed it. I cupped a hand to my ear.

“Monkey God!” I heard faintly through the glass.

“Having fun?” asked Catherine, appearing beside me.

“I thought it was a dog,” I said.

The shopkeeper did the trick again, pleased to have doubled his audience.

We ate lunch in a cheap restaurant that Catherine knew. She said it had to be cheap, given that we had left the antique district with the porcelain Monkey God in my pocket, loosely bound in bubble wrap. It turned out to be not less expensive than the ivory figures, but more. But I wasn’t overly worried at the cost. In fact, the cost was the point. I think I wanted Catherine’s scandalized reaction to my extravagance more than I wanted the figurine itself.

Catherine wanted to wait until the late afternoon, so the heat didn’t tire us out as we walked around the grounds of the shrine she wanted to visit, which she had described as her favorite in the city. So we let lunch drag on a while. We drank tea, and let the waitress keep refilling the cups, and left the bill unpaid on the table until the shadows of the passersby were just starting to lengthen.