14.

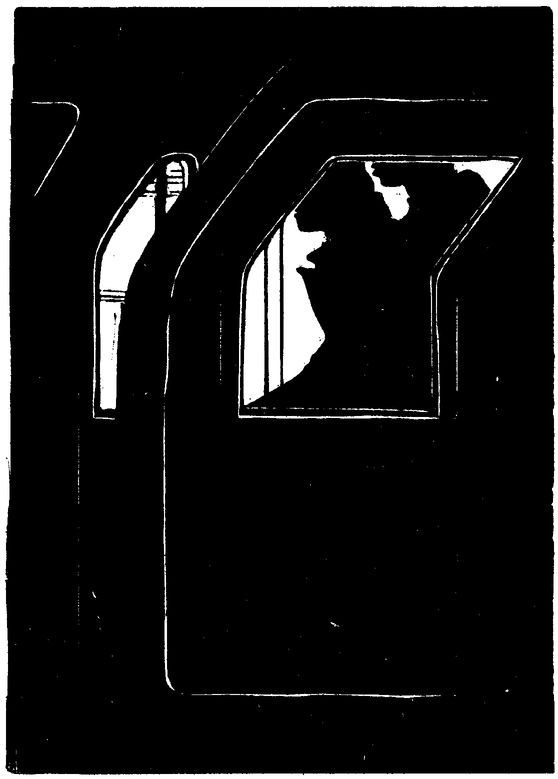

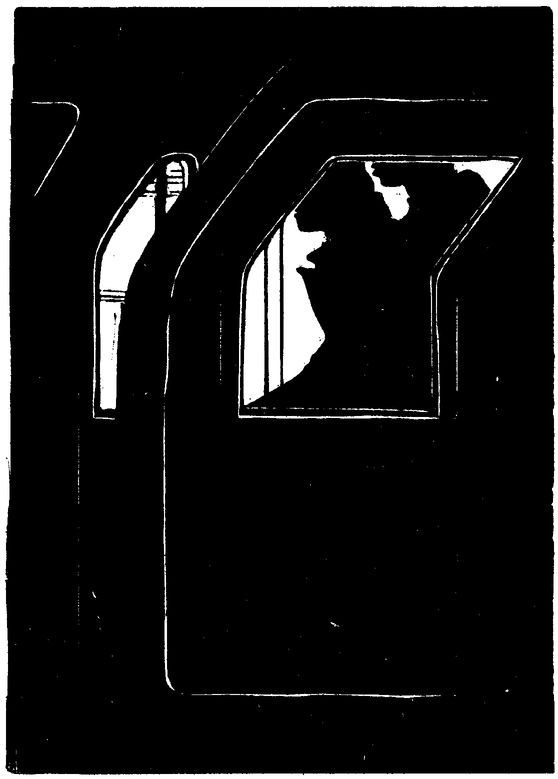

On the other side of the windows of the train, I saw two things.

The first was an advertisement, running above the windows. A photograph showed Anthony, smiling brightly, and behind him his bland family. The advertisement read: Fresh milk, fresh coffee. Some things are just meant for each other. I wasn’t sure which of the two products he was selling, but I was glad to finally make sense of him.

The second thing I saw was the four young men, getting ready to move into the next carriage, where they would intimidate the girl who was reading her book, and shortly afterwards, attack me.

I call them young men, maybe because it makes me more comfortable about the ease with which they kicked me into oblivion, but in truth they were boys. The youngest was no older than fifteen. The oldest was possibly eighteen or nineteen. No shame, I suppose, in being beaten up by four teenagers—but still, it bothered me. Not as a physical thing, not as a comparison of speed and strength: as a disempowerment.

I wondered, as I looked at them through the grubby glass, if I would hear myself as I protested at the first moment of their attack. I had a horrible feeling that I would hear the same despairing tone I had half heard during the mind loss. A boring man, despairing weakly. This is what I am? Oh no, oh God, oh dear, no ... Nasal, perhaps, because I’d just had my nose broken.

It made me feel angry. It made me want to pass through the window and occupy their space before they occupied mine. Let me kick them into a coma. See how they cope!

But I couldn’t attack them. I was a ghost. All I could do was press up a little closer to the window and follow them as they pulled open the doors between the carriages and moved through.

I’ve said it already: the girl was brave. The way she kept her place in the book with her finger even while holding on to her bag and pushing the boys away.

I continued past the girl until I was positioned directly opposite where I sat. Which made me wonder: When I had thought I was looking at my own reflection in the glass, had I actually been looking at myself? Glimpsing the ghost of coma future?

Whatever—I wasn’t as brave as the girl. I could see that clearly enough, from the way my eyes flicked sideways to see what was happening farther down the train, and from the way that those eyes widened as the girl began to walk towards me.

But perhaps I was brave too. When the girl said, “Excuse me, do you mind if I sit here?” I studied the way I shook my head and held her gaze. I remember that at the time I had hoped the returned gaze was reassuring to her. And from my new perspective, I could see that it was reassuring. The gaze seemed to say, Don’t worry. If anyone is going to get beaten up around here, it’s me.

Then the boys were on us, and the girl’s wrist was grabbed, and her arm was twisted, and she shouted.

As I stood and raised a hand and intervened, I actually felt a little proud of myself. Not so much for intervening, for what I was doing at that moment, but because I knew the extremely odd sequence of events that was about to unfold for the man in the carriage. I knew precisely what he would face, and how he would cope, and I didn’t feel he had done so badly.

Finally

through the side windows of the train, as if I were hovering between the external glass and the subway walls, I saw myself walking backwards through the carriage, holding up my arms around my face and upper body. The young men were attacking me. Many of their blows looked as if they glanced harmlessly off my head and shoulders, and some missed me altogether. But some blows connected hard.

My movements were slow and confused. My hands swung out a couple of times to ward the men off, but the gesture looked no more fierce than if I were swatting away a fly. Soon my legs buckled, and I fell backwards against the seats, then rolled down to the floor. From my position outside the carriage, I watched as the young men kicked me into unconsciousness.