“Coming from Providence on its own trains of red and yellow steel cars, Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus arrives in Hartford this morning.”

You could almost hear the buzz of excitement in the air over Hartford, Connecticut, leading up to the arrival of the one and only Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Posters plastered on buildings and storefronts boasted the show’s highlights: Mr. and Mrs. Gargantua the Great, a pair of enormous gorillas; aerialists performing a Cloud Ballet; and a pantomime by the famous clown Emmett Kelly.

Emmett Kelly was a “tramp clown.” He dressed in drab colors and painted a large white frown and black stubble on his face. His routine was different from those of other, more colorful clowns, whose slapstick antics were intended to make people laugh. Instead, without speaking a word, Kelly made people feel sorry for him. Poor Weary Willie, the audience thought, chuckling as he tried unsuccessfully to sweep a circle of light into a dustpan. By the summer of 1944, Kelly had been traveling with the Ringling Bros. circus for three years, and Weary Willie was one of its most popular attractions.

In the 1940s, a trip to the circus was a rare treat. Though Hartford was a thriving city during the years of World War II, the average income was only about $52 a week. Many fathers and husbands served in the military overseas. More women entered the work force when they found themselves raising their families on their own. Kids often contributed to the family income or made their own pocket money by delivering groceries or newspapers. Buying food and paying rent took priority, and circus tickets were expensive—the nicer grandstand seats cost $1.20 each. But for an occasion as big as the Ringling Bros. circus, families saved their pennies all year long.

A poem in the circus program promised “the real Fairyland is right at hand, it’s where the circus holds sway.” Going to the circus was not only a delight for children; it gave everyone a break from the real world. Emmett Kelly claimed people loved the circus because “they want to laugh and forget their troubles.” Worries about food rationing or bomb shelters faded away amid the bright colors and lively music of “The Greatest Show On Earth.”

Even the government thought the circus was good for the morale of the country. During the war, railroad travel was restricted so that military supplies and machinery could be transported quickly and efficiently. However, the Ringling Bros. circus was given special permission to use the rails to travel from town to town. The government also used the circus to promote the sale of war bonds. People who bought bonds were loaning their money to the government to pay for the war. After the war was over, people could cash in the bonds and get their money back, plus interest. In addition, anyone who bought war bonds was given free circus tickets.

With many men fighting overseas, there was a shortage of staff to run the circus. Ringling Bros. placed this advertisement in Billboard magazine: “Good Salary and Expenses Offered to Ambitious Young Men Who are Not Subject to Call in the Armed Forces. Learn the Art of Outdoor Advertising with the Greatest Show On Earth.” They also hired local boys in the towns where they stopped. Too young to enlist in the military, the boys had free time and were eager to help out. They took care of the animals by filling their troughs with water from fire hydrants, and they spread straw and sawdust on the ground. The older, stronger boys served as roustabouts. Roustabouts helped set up and take down the tents and did other physical labor around the grounds. Young boys made 50¢ for a day’s work or received free passes to the show. Many kids thought that being part of the action and getting a free ticket to see the amazing Ringling Bros. circus was even better than money.

At the end of June 1944, 15-year-old Robert Segee thought he’d like to get a closer look at The Greatest Show On Earth. Robert lived with his parents and siblings in Portland, Maine. He was a tall boy, and strong, much bigger than other kids his age. Robert had few friends, though, and he hadn’t done well in school. Because he had been kept back several times, he was older than all his classmates. Brooding and quiet, Robert spent most of his time alone in his room. To make matters worse, Robert and his father did not get along. Mr. Segee bullied Robert and yelled at him often. He always seemed to be punishing Robert for small mistakes.

So Robert ran away from home and joined the Ringling Bros. circus when it came to Portland. The manager of the lighting department, Edward “Whitey” Versteeg, gave Robert a job setting up the wiring and lights in the big top. Later, Robert proudly told people he had even worked the main spotlight during the shows.

Everyone in the circus family had been looking forward to the summer season. The performers and workers got settled in the train cars in which they lived and traveled. Animal trainers practiced their acts with the elephants and the panthers. The season had been off to a good start until the show reached Portland. There, the crew discovered a small fire on the tent ropes. Luckily, it was put out immediately and caused no real damage. The show went on without incident.

At the next stop in Providence, Rhode Island, bad luck struck again when a small blaze appeared on a tent flap. Like the flame in Portland, it was quickly extinguished before it did any harm. There was always dry straw on the ground for the animals, and cigarette smoking was common. So the staff wasn’t alarmed when small fires popped up once in a while. The seat hands (circus workers who manned the bleachers and grandstand) were always able to put them out quickly with buckets of water placed throughout the tent. A cause for the fires in Portland and Providence was never determined, and the traveling show continued on its way.

As the circus was rolling into Hartford, the Cook family was enjoying a reunion. Nine-year-old Donald, eight-year-old Eleanor, and six-year-old Edward were visiting their mother, Mildred. Life had not been easy for the Cooks. Mildred’s husband had recently abandoned his family, and Mildred suddenly needed a way to support her children. She got a job at an insurance company in Hartford and left Donald, Eleanor, and Edward in the care of her brother and sister-in-law, Ted and Marion Parsons, in Southampton, Massachusetts. While Uncle Ted and Aunt Marion were like a second set of parents to the children, they were excited about this special visit with their mother. They had taken the train from Southampton and couldn’t wait to see the wild animal acts and silly red-nosed clowns.

The Ringling Bros. three-ring circus was scheduled to perform four shows in Hartford: two on July 5, and two on July 6. Mildred had tickets for the matinee on July 5, but when she and the children arrived at the circus grounds, they saw that the tents were not yet up. There was no smell of fresh, buttery popcorn in the air. There were no sideshow barkers enticing people to gawk at human oddities. The grounds were a mess of canvas tenting, ropes, and half-assembled food stalls.

Confusion on the tracks had held up the circus train for several hours on its way from Providence to Hartford. The performers and crew finally reached the grounds at 350 Barbour Street around noon, but it was too late. There was not enough time to get the big top and the side tents ready for the matinee. Disappointed circus-goers clutched their tickets, wondering what to do. The staff told everyone to return for the matinee the following afternoon. Mildred exchanged her tickets and assured her children that they would not miss out on the show.

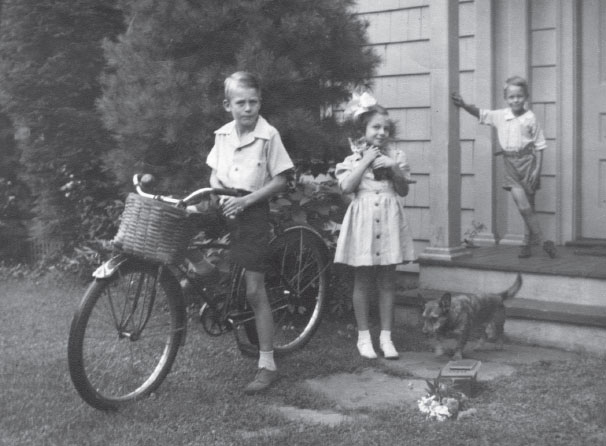

Donald, Eleanor, and Edward Cook.

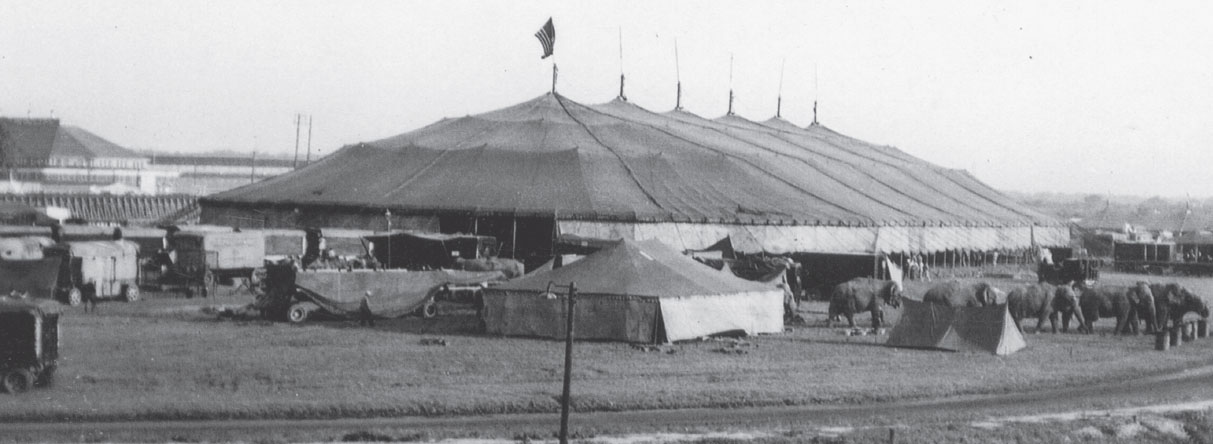

The Ringling Bros. crew was disheartened at the train’s late arrival. But there was still work to do, including setting up the enormous big top. The main tent was massive. It was 450 feet long and 200 feet wide—one-third longer than an entire football field. Elephants pulled on the ropes, hoisting 75,000 square feet of heavy canvas into position. Trainers got the animals comfortable, and the cook prepared food for the tired, hungry crew.

The Ringling Bros. circus big top tent, circa 1944.

After the grounds were ready, Robert Segee ate with the rest of the crew and the performers in the mess tent, waiting for the evening show to begin. Many performers were superstitious about missing a show and considered their late arrival a bad omen.