“The last word in high wire thrillers, new hazardous and hair raising feats by world acclaimed artists who shake dice with death at dizzy heights.”

More than 6,000 people attended the circus on that hot July 6 afternoon. Circus programs became fans, and men pulled handkerchiefs from back pockets to wipe their sweaty brows. “The air was stagnant. There was no breeze,” Arthur S. Lassow recalled. With high humidity and temperatures in the 80s, the muggy air seemed to cling to the skin. It’s no wonder the stand selling glass bottles of Coca-Cola was a big hit. A long chug of ice-cold soda pop hit the spot.

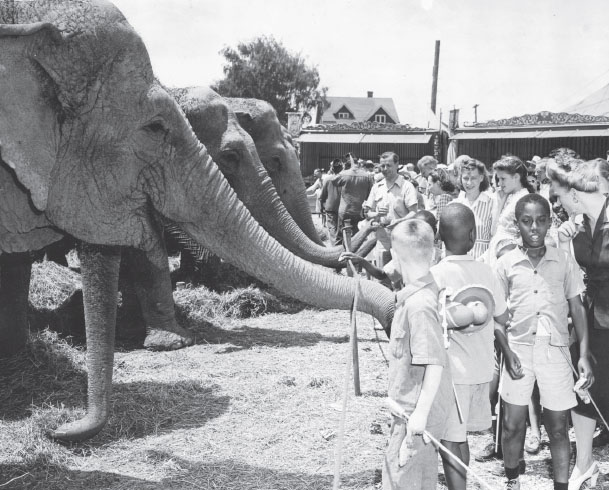

Before entering the big top, people could wander through the animal menagerie—a traveling zoo where you could see the animals up close. The Ringling Bros. circus was home to many unusual and amazing creatures including: 1 anoa buffalo, 1 cassowary, 1 harte-beest, 1 pygmy hippopotamus and 2 large common hippos, 1 kangaroo, 1 llama, 1 mandrill, 1 springbok, 1 white-bearded gnu, 2 bears, 2 cranes, 2 donkeys, 2 giraffes, 2 gorillas, 2 guanacos, 2 king vultures, 2 lions, 2 tigers, 2 zebras, 3 chimpanzees, 3 cockatoos, 5 camels, 19 rhesus monkeys, 30 elephants, and 117 horses!

Betty Lou, the pygmy hippo, was a crowd favorite. She kept cool by wading in the water of her tank as patrons smiled over her. Betty Lou was one of the animals that had survived a fire in 1942, when a spark from a passing train had ignited the menagerie tent. The flames had spread quickly, and the staff could do little to stop it. All hands did their best to lead the animals to safety. No circus workers or audience members were hurt, but 45 animals died. Now, two years later, many of the animals in the menagerie were survivors of that tragedy. Old wounds had healed, and new animals had joined the show. People once again marveled at the long necks of the giraffes and the big humps of the camels. The disaster of 1942 seemed a distant memory.

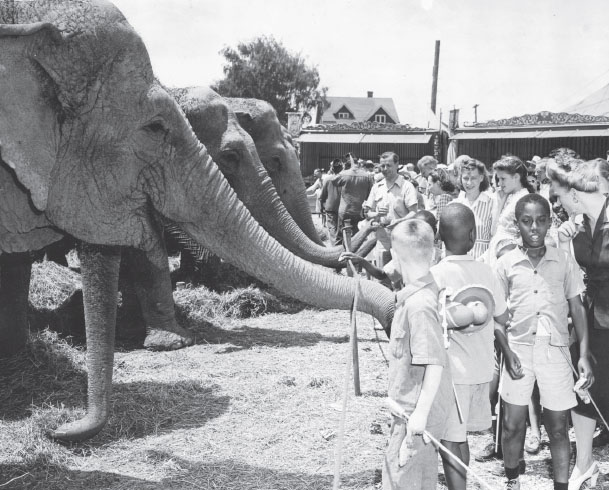

Besides the animal menagerie, the circus offered sideshows before the main event. Sideshows presented a curious assortment that included sword swallowers, bearded ladies, and tattooed men. In one sideshow attraction, Gargantua the giant gorilla and his “wife,” another large gorilla, sat quietly in their cage as people ogled them through the bars. Today, sideshows are considered cruel and inappropriate, but in the 1940s they were common. Among the acts that thrilled audiences in 1944 were Rasmus Neilsen, the tattooed strong man; Miss Patricia, swallower of neon tubes; Señorita Carmen, snake trainer; the Doll Family (Harry, Gracie, Daisey, and Tiny), the “world’s smallest people”; Percy Pape, the living skeleton; Louis Long, the sword swallower; Egan Twist, the rubber-armed man; Kutty Singlee, the fireproof man; and Mr. and Mrs. Fischer, a giant and giantess.

Children visit the elephants in the menagerie.

All around the grounds were stalls where vendors sold programs and other souvenirs. One vendor even sold chameleons on little string leashes. When eight-year-old Donald Gale’s mother bought him one, he carefully tucked the lizard into his shirt pocket to keep it safe.

Families enjoyed hot dogs and ice cream. Children’s faces were sticky with cotton candy, and the intoxicating smell of freshly roasted peanuts lingered in the air. Residents of the nearby neighborhood set up lemonade stands and sold cool drinks.

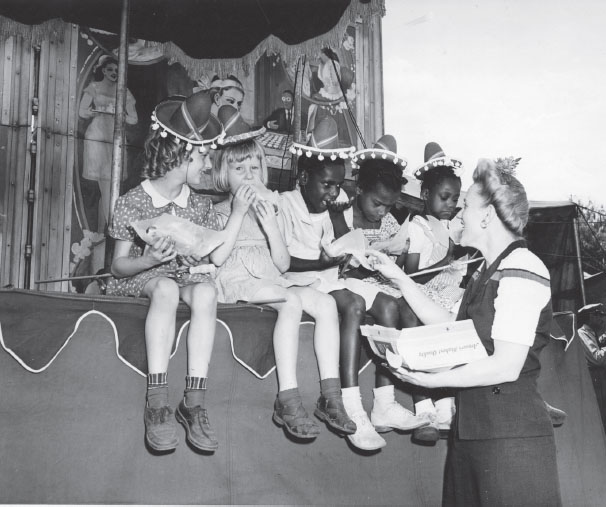

Nine-year-old Eugene Badger got to go to the circus as a birthday treat. Eugene and his father headed to the circus grounds while Mrs. Badger went to the Red Cross to donate blood. Eugene and his father did not spend much time outside the tent before the show. They couldn’t afford things like candy apples and sideshows, which cost extra. Instead, they made their way through the main entrance on the west end of the tent. Mr. Badger had a medical condition and used crutches to get around, so Eugene helped his father as they walked the length of the tent to their seats in the northeast bleachers.

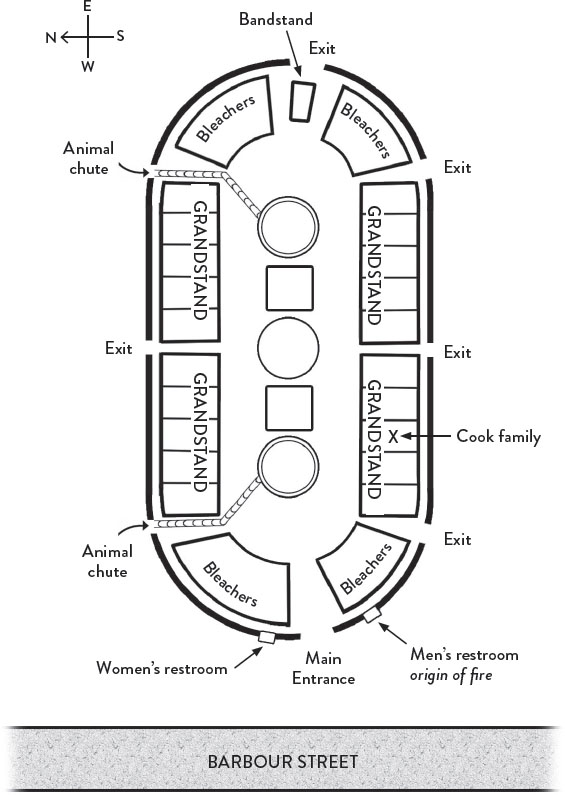

Children enjoy a treat before the show.

Bleacher seats took up the four corners of the tent. The grandstand seats ran along the sides, where folding chairs were set up on wooden boards. These seats had backs, making them more comfortable and therefore more expensive. Unlike today’s big arenas where seats are bolted to the floor, the grandstand chairs were free standing. People had to be careful not to knock over the chairs as they walked across the wooden planks.

The Cook family sat in the southwest grandstand. Like everyone else in the tent that day, Mildred and her children were eager to laugh at the clowns and to gasp in wonder at the acrobats and animal tamers. It was hot inside the tent, but at least the canvas roof gave protection from the blazing sun.

As the band warmed up the clowns put on their makeup and the Flying Wallendas, the famous trapeze artists, got ready to take the stage. Seat hands stationed themselves beneath the bleachers. During the show they would pick up trash and watch to make sure no one snuck in without paying. They also had the very important job of guarding against accidents, including fires. Smoking was not allowed in the big top, but this rule was difficult to enforce. In the 1940s, smoking was more common than it is today. Buckets of water were placed beneath each seating section before the show. If a seat hand saw a carelessly tossed cigarette or burning match fall from the stands, he could quickly put it out.

Map showing the interior of the big top tent.

At 2:23 PM, the show began. Up first was a comedy act in which girls in bright sequined costumes “tamed” a performer dressed in a lion suit. Next came May Kovar and Joseph Walsh and their performances with real wild cats on opposite ends of the tent. Known as the “lion queen” of the circus, May astounded audiences with her bravery and control of the large, snarling felines. In Hartford, May deftly led 15 leopards, panthers, and pumas through their tricks as the audience watched, spellbound. Meanwhile, Joseph performed with lions, polar bears, and Great Danes.

“I was awestruck at the enormity of how large the [big cats] really were, never having seen a wild animal like that,” circus-goer Anthony Pastizzo recalled. “And to see them performing with a human inside that cage, I was really amazed at how anyone gathered enough courage to work with an animal that size and as ferocious as that [cat]!”

May performed with masterful artistry when most people would be shaking with fear. In fact, just the year before, May had been attacked by one of her cats during a performance. A jaguar had leapt off of its perch toward her, teeth bared. May fended him off, but the jaguar attacked a second time, digging its dagger-sharp claws into her chest. Her injuries had required dozens of stitches. Performers like May enjoyed their work, but it could be a dangerous job.

At the end of their act, May and Joseph left the floor, and the Flying Wallendas began to take their places on a platform 30 feet in the air. The Wallendas—Karl, Helen, Joe, Herman, and Henrietta—were world famous for their performances. Karl and Helen’s daughter Carla, only four at the time, would eventually join them. The troupe’s high-wire pyramid was especially astounding. Joe and Herman pedaled bicycles on the high wire while holding a wooden board between them. On this board, Karl balanced himself precariously on a chair. Helen miraculously completed the pyramid, standing atop her husband’s shoulders.

As the Wallendas climbed rope ladders to their platforms, the busy circus staff kept the show moving on the ground. May and Joseph guided their animals into long steel and wooden corridors called chutes, which led to cages outside the big top. Because the chutes blocked both the northeast and northwest exits, they needed to be removed after the animals had passed through. Moving the chutes was a difficult task, and because the circus was short on staff, some of the seat hands had to leave their stations to help.

At about 2:40 PM, no seat hands were left to monitor the area by the southwest bleachers. It was then that someone first noticed a small flame flickering on the side wall of the tent.