Not enough circus staff were on hand to fight the fire.

Not enough circus staff were on hand to fight the fire.“Seven officials and employees of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Combined Shows, Inc., were held criminally responsible … for Hartford’s disastrous circus fire last July 6.”

In the days and months after the Hartford circus fire, people gathered their families and friends close. They hugged their neighbors who had come home safe and unharmed. They visited patients in the hospitals. They planned and attended funerals. One memory that stands out among the people who lived through the fire is how everyone in the community supported each other during the bad times.

The citizens of Hartford took care of one another, but had the managers of the Ringling Bros. circus cared for the safety of their guests when they beckoned them to come see “The Greatest Show On Earth”? And what about the city of Hartford? Did the city have an obligation to the people who had come from down the street and across the state to see the circus? Fingers pointed at both Ringling Bros. and Hartford, but who was to blame?

In the 1940s, fires were not uncommon at circuses. At that time, many people smoked, and a carelessly thrown match or cigarette could easily start a fire on the hay strewn on the ground for the animals, especially if the weather had been very dry. Usually, circuses were well prepared to quickly extinguish any fires that might pop up. Unfortunately, in Hartford, the Ringling Bros. circus did not follow proper safety procedures.

An investigation by the Hartford Board of Inquiry revealed the following:

Not enough circus staff were on hand to fight the fire.

Not enough circus staff were on hand to fight the fire.

The nearest fire hydrant was 300 feet from the main entrance, and the circus’s fire hoses did not fit the city hydrants.

The nearest fire hydrant was 300 feet from the main entrance, and the circus’s fire hoses did not fit the city hydrants.

Only 24 buckets of water, and no fire extinguishers, were placed throughout the tent.

Only 24 buckets of water, and no fire extinguishers, were placed throughout the tent.

The steel animal chutes blocked two of the main exits.

The steel animal chutes blocked two of the main exits.

Staff had failed to post NO SMOKING signs inside the main tent.

Staff had failed to post NO SMOKING signs inside the main tent.

Police Commissioner Hickey also reported that the big top tent had been waterproofed with a highly flammable mixture of 1,800 pounds of wax and 6,000 gallons of gasoline. We might be shocked by this method of waterproofing today, but it was common practice at the time. The Ringling Bros. circus had treated the canvas big top the same way for a number of years before the fire. John Ringling North, then a director on the board of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows, Inc., claimed that he had tried to obtain fireproof tents in 1944. However, North said, the government denied access to these tents because such specialty supplies were reserved for the war effort.

Years later, a report by Henry Cohn, a lawyer for the state of Connecticut, confirmed that “the armed forces had exclusive control of the only proven flame-retardant waterproofing solvent for use on their canvas tents.” He goes on to note, “Other circuses claimed to have found equally satisfactory and safe treatments; the Ringlings later claimed to have tested the available chemicals and found they were quite flammable. Also when the tent was dragged to the next location, the solvent was easily scraped off.” On the other hand in 1991, circus fire researcher and journalist Lynne Tuohy suggested that perhaps the Ringling Bros. circus simply didn’t want to use the safer fireproof tents because they were heavier and required more time and manpower to set up.

Pieces of the curved steel animal chute can be seen in the foreground. A still-assembled chute can be seen in the background between two sections of the grandstand. Boxcars from the circus train also blocked that exit.

It is surprising that the Ringling Bros. circus continued to use flammable tents, even when they’d had trouble with them before. Fires had caused great damage to the big top in 1910 and 1912, though no one died in these instances. Then there was the horrible fire in the animal menagerie tent in 1942. The frightening similarity between that fire and the one in Hartford was how the circus had waterproofed the tents—both with the mixture of wax and gasoline. The circus had not learned from its mistakes.

So what about the city of Hartford? Did it have a role in not preventing the disaster? Certainly the aftermath of the fire was handled with authority and efficiency. But why didn’t anyone from the Hartford fire department notice the safety violations? The simple answer is that neither the fire department nor the police department were expected to do anything to make sure the circus was safe. In fact, the fire department was never officially told that the circus was in town.

When the circus got into town on July 5, it was not properly inspected. Because the circus train had arrived late, the grounds were not set up when Charles Hayes, the building inspector, arrived to check that safety precautions had been met. His inspection wasn’t a requirement in Hartford, but it was customary to have someone check things out. Hayes returned later in the afternoon, but things still weren’t quite ready. He claimed that since the circus had always complied with fire safety regulations in the past, he was sure this year would be no different. Because the setup was not complete when Hayes left the grounds, he had not checked the fire extinguishers or the fire hoses. He did not even check the tent to make sure all the exits were clear. Hayes gave the circus the go-ahead anyway.

Downtown, Police Chief Charles Hallissey issued the circus a permit to perform on the Barbour Street lot, even though he had not checked the safety of the circus grounds or the tents either. Hallissey hastily filled out the permit form, not even bothering to write the date, and in exchange received 50 free passes to the show.

While Connecticut did not require the local fire department to be present at public events, several police officers were assigned and stationed throughout the tent. Detectives Paul Beckwith, Edward Lowe, and Thomas Barber had been onsite, and they remained on the case for some time after the disaster as well. What began as a routine assignment turned into a massive disaster response operation.

The official report of the Hartford County coroner cleared the city from any blame. “The report finds no legal responsibility to inspect circuses placed upon city fire, police, or building departments.” Instead, the entire blame for the disaster was placed upon the Ringling Bros. circus. Six circus officials were sent to jail because of the unsafe conditions inside the big top tent. On February 21, 1945, the men were found guilty of involuntary manslaughter.

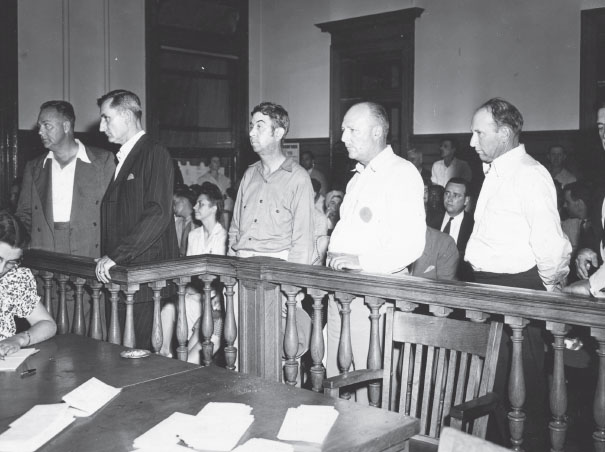

Three circus officials were sentenced to one to five years in the state prison: James Haley, the circus’s vice president and director, convicted for knowledge of unsafe conditions; general manager George W. Smith, convicted for negligence; and boss canvasman Leonard Aylesworth, who was in charge of supervising fire prevention, convicted for deliberately leaving his post and neglecting to appoint someone to supervise the fire equipment in his place. (On the day of the fire, Aylesworth was in Springfield, Massachusetts, preparing the next location.) Edward “Whitey” Versteeg, chief electrician, and William Caley, seat hand, were each sentenced to one year in prison; Versteeg for failing to distribute fire extinguishers and Caley for leaving his designated post. David Blanchfield, superintendent of rolling stock, was given six months for obstructing the tent’s exits with his trucks. Some sentences were later reduced, but all six men served time in connection to the fire.

Ringling Bros. circus managers in court. Left to right: George W. Smith, James Haley, Edward “Whitey” Versteeg, Leonard Aylesworth, and David Blanchfield.

The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows, Inc. was ordered to pay $4 million to compensate people for their losses. Today that figure would be close to $42 million. It was a large enough sum to bankrupt the circus. Fortunately, the lawyers for the victims were clever. They arranged for the circus to continue to function because, they argued, if the circus were to close down, there would not be enough money to pay the damages owed to people. It was crucial that Ringling Bros. continue to put on their show. Incidentally, this plan worked out for the circus as well. It could be argued that if the lawyers had not come up with this plan, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, the most popular circus in the United States, would not be around today.

William Caley began his prison sentence immediately, but the other convicted circus employees remained free long enough to help prepare for the upcoming 1945 spring season. A portion of the money earned each season would help pay the thousands of claims made by circus fire survivors and the families of the victims. Eventually, the Ringling Bros. circus paid every cent of that debt.

Regardless of who was to blame, many people wondered, could this kind of tragedy happen again? The mayor of Hartford decided to make some changes in how circuses and other outdoor events were handled by the city. Hartford became an example that other cities across the country would follow. In January 1945, officials passed a law that required careful inspections of events held in tents. The grounds, seats, aisles, exits, and first-aid facilities must be checked by police and fire departments. Smoking and overcrowding in the tents would not be allowed. All tents must be fireproof.

Officials also realized that every second counts when ambulances and fire trucks are on their way to an emergency. Before the circus fire, emergency vehicles did not always use their flashing lights to help them move quickly through traffic. Now, it was required for them to be on at all times.

Despite the new safety inspections, it was years before anyone in Hartford wanted to attend the circus again. As they grew older, survivors of the fire refused to take their children to circuses. Many had a lifelong fear of crowds. The Ringling Bros. circus performed in other cities in the years after the fire, but it did not return to Hartford again until 1975, more than 30 years later. By then, the circus was no longer performing inside a tent, but instead held its shows in indoor arenas.

Negligence on the part of both Ringling Bros. and the city of Hartford contributed to the tragedy. But was the fire, in fact, accidental? Was it possible that, when the seat hands left their stations to move the animal chutes, someone had intentionally put a match to the canvas?